Investigations of the Use of Invasive Plant Biomass as an Additive in the Production of Wood-Based Pressed Biofuels, with a Focus on Their Quality and Environmental Impact

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomass Pellet Production

2.1.1. Chopping and Milling

2.1.2. Pellet Formation

2.2. Identifying the Key Characteristics of Biomass Pellets

2.2.1. Moisture Content Analysis

2.2.2. Pellet Density

2.2.3. Compression Resistance of Pellets

2.2.4. Pellet Strength Testing

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.2.6. Elemental Composition, Ash Content, and Calorific Value Evaluation

2.2.7. Evaluation of Burning Emissions

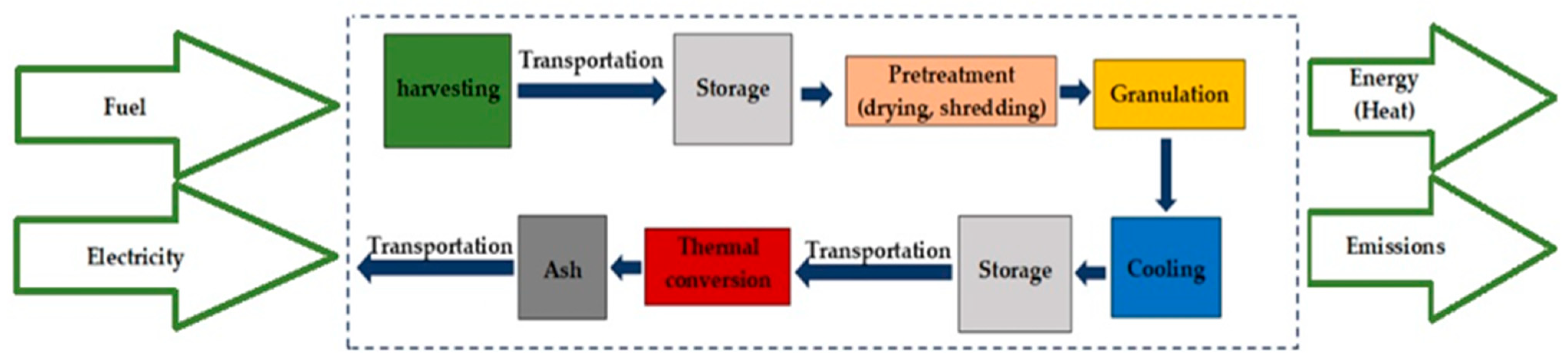

2.3. Life Cycle Assessment

2.3.1. Functional Unit

2.3.2. System Boundary

2.3.3. Inventory Analysis

Biomass Harvesting

Transportation

Ash Utilization

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Parameters of Produced Biofuel

3.1.1. Biomass Accumulation and Harvesting

3.1.2. Physical Properties of Produced Solid Biofuel

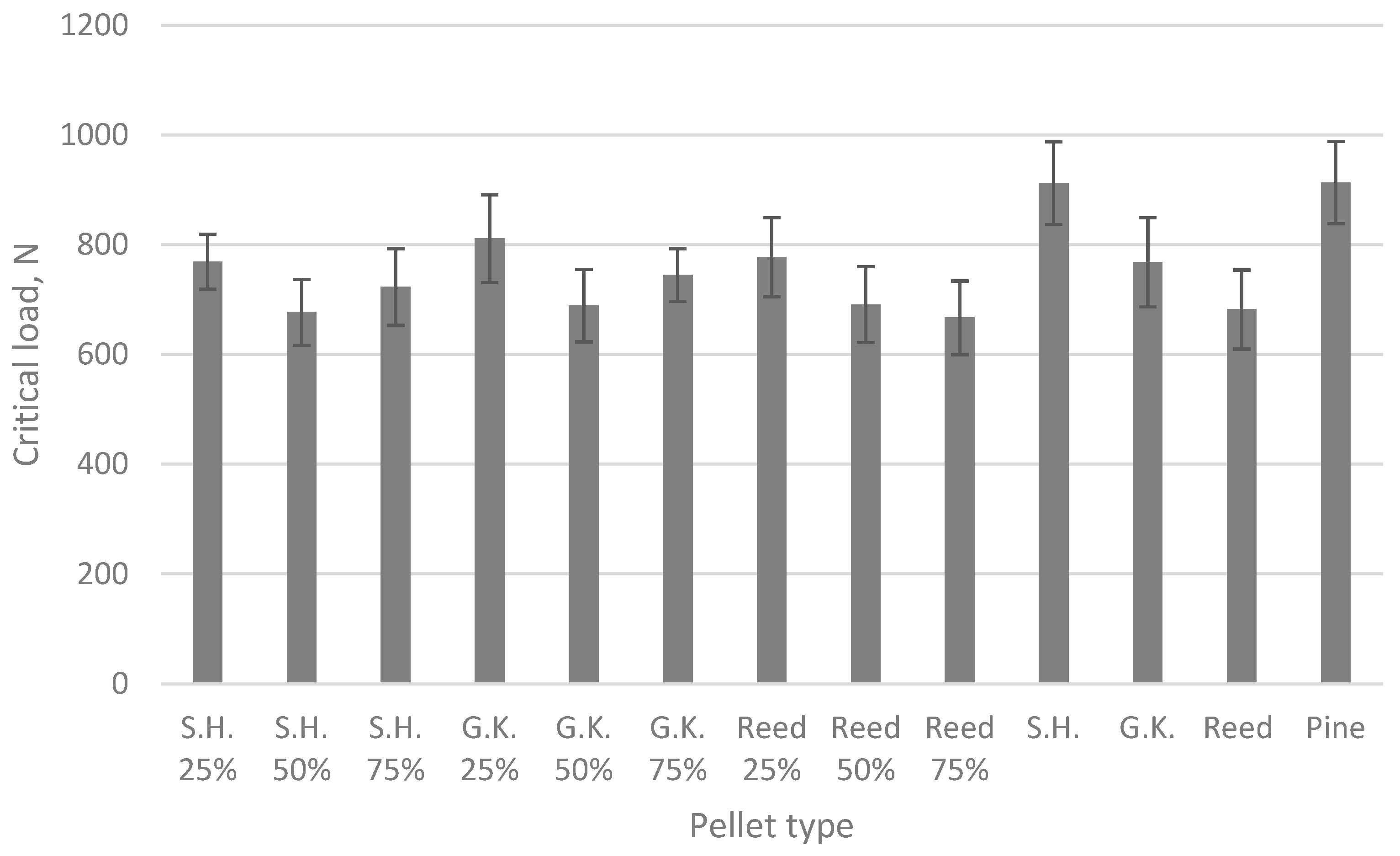

3.2. Solid Biofuel Strength Determination

3.3. Elemental Properties and Emissions of Produced Solid Biofuel

3.3.1. Elemental and Energetic Properties

3.3.2. Emissions from Solid Biofuel Burning

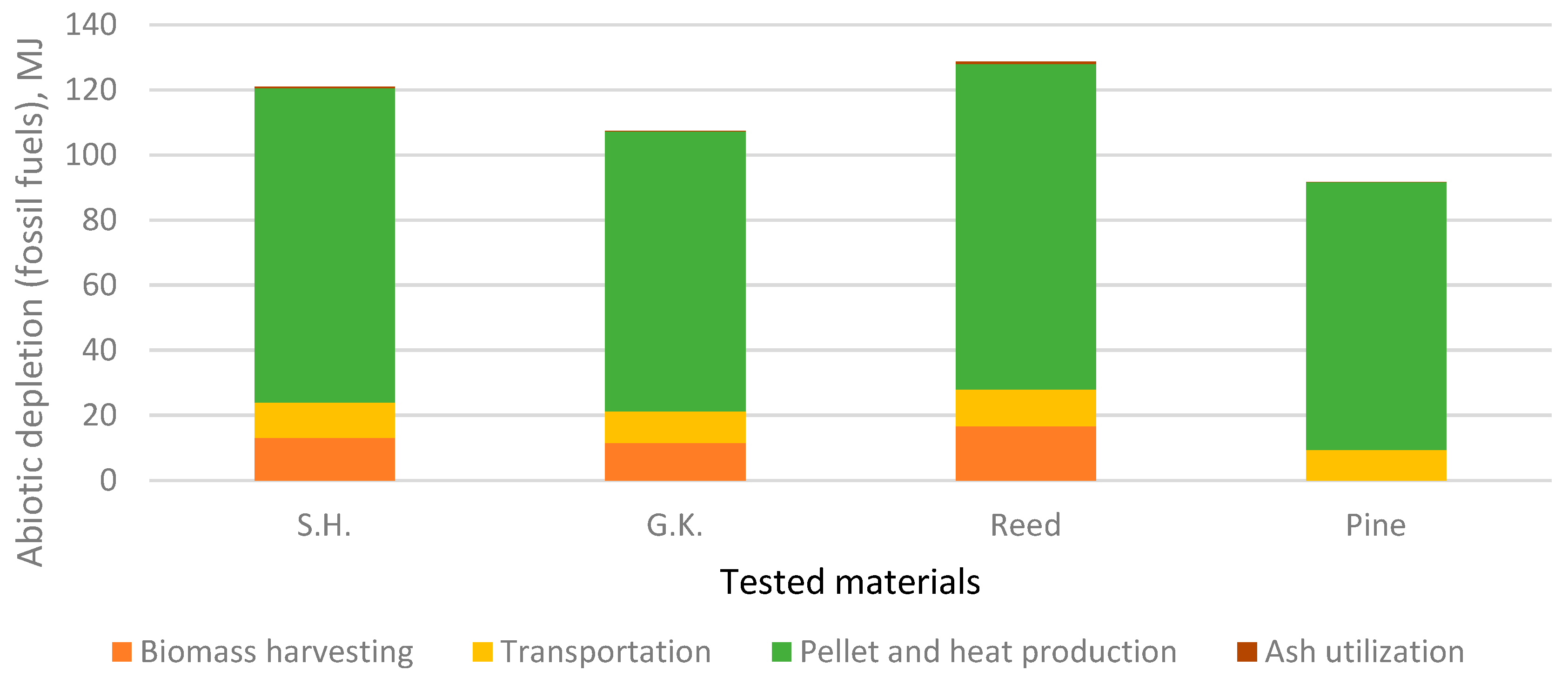

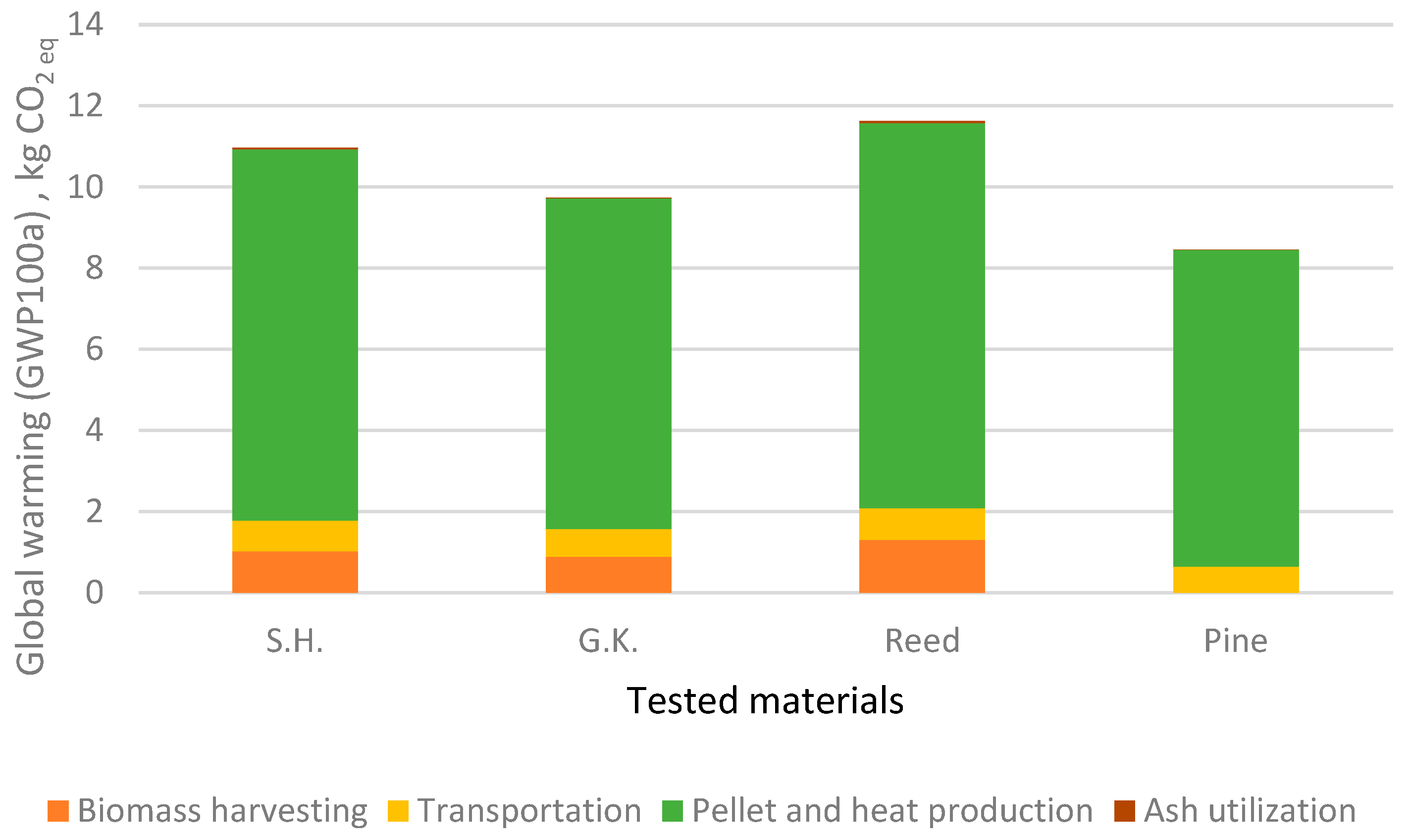

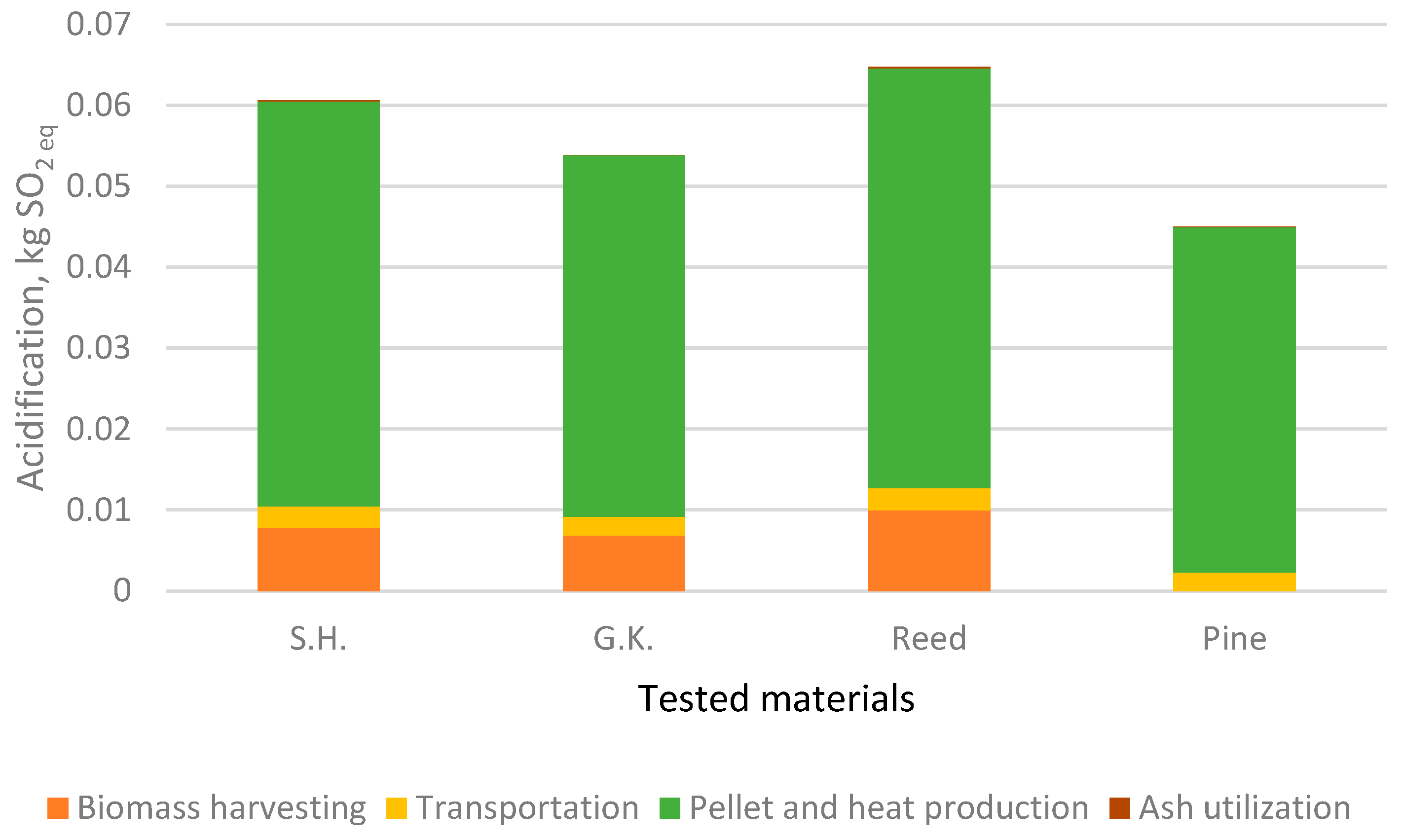

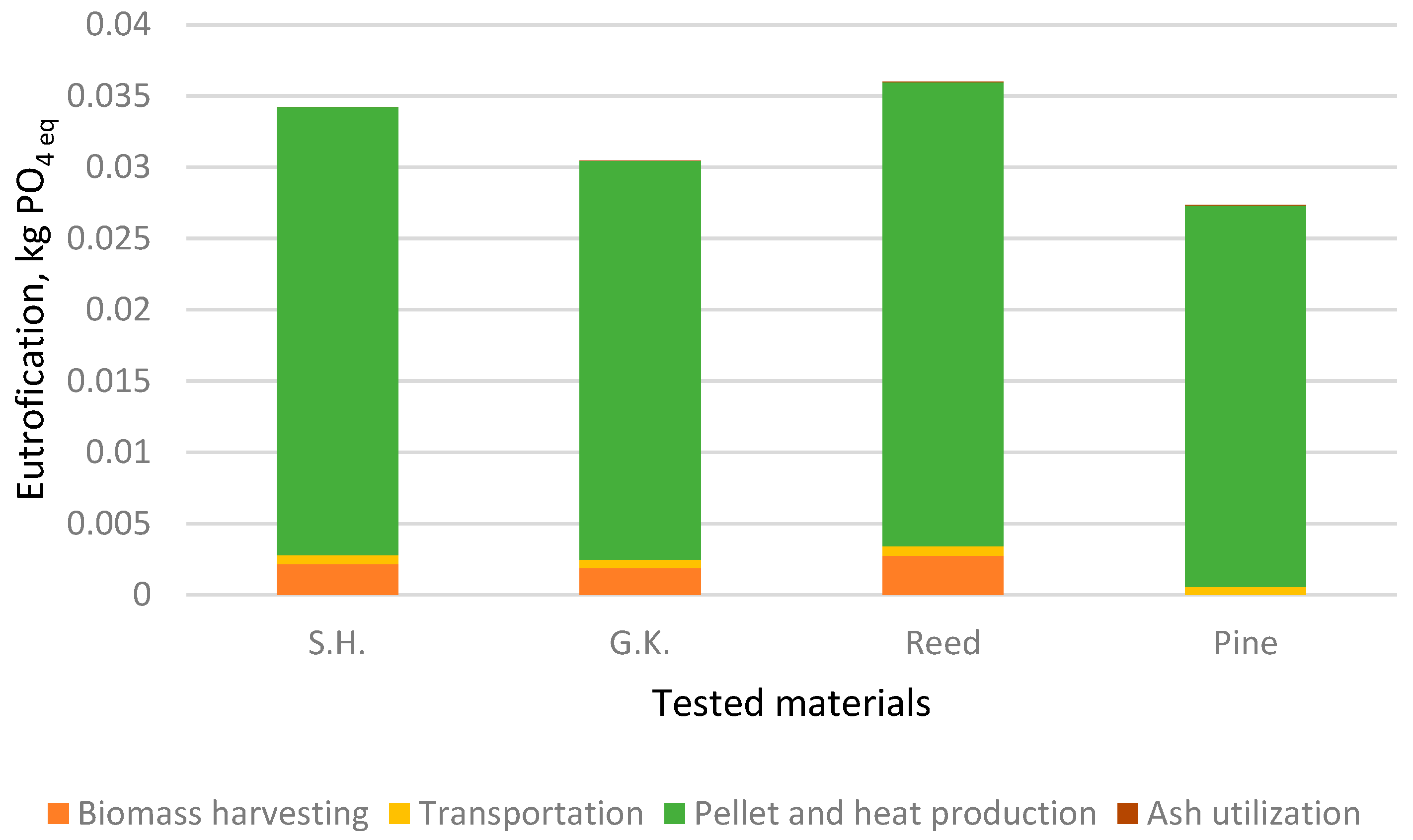

3.4. Life Cycle Assessment of Invasive Plants

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| S.H. | Sosnowky’s hogweed |

| G.K. | Giant knotweed |

| FU | Functional unit |

| AD | Abiotic depletion |

| ADF | Abiotic depletion (fossil fuels) |

| GWP | Global warming (GWP100a) |

| ODT | Ozone layer depletion (ODP) |

| HT | Human toxicity |

| FWAE | Fresh water aquatic ecotoxicity |

| MAE | Marine aquatic ecotoxicity |

| TE | Terrestrial ecotoxicity |

| PO | Photochemical oxidation |

| AP | Acidification |

| EP | Eutrophication |

| HCV | Higher calorific value |

| LCV | Lower calorific value |

References

- Karthik, V.; Periyasamy, S.; Varalakshmi, V.; Mercy Nisha Pauline, J.; Suganya, R. Chapter 15—Biofuel: A prime eco-innovation for sustainability. In Environmental Sustainability of Biofuels; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Vareas, V.; Kask, U.; Muiste, P.; Pihu, T.; Soosaar, S. Biofuel User Manual; Zara: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2007; 168p. (In Lithuanian) [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, J. The Evolutionary Ecology of Invasive Species; Charlote Cockle: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2022; pp. 1–209. [Google Scholar]

- Halmova, D.; Feher, A. Possibilities of utilization of invasive plant phytomass for biofuel and heat production. Acta Reg. Environ. 2009, 6, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mishyna, M.; Laman, N.; Prokhorov, V.; Fujii, Y. Angelicin as the principal allelochemical in Heracleum sosnowskyi fruit. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowicz, O.; Zaba, C.; Nowak, G.; Jarmuda, S.; Zaba, K.; Marcinkowski, J.T. Heracleum sosnowskyi Manden. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2012, 19, 327–328. [Google Scholar]

- Kappes, H.; Lay, R.; Topp, W. Changes in Different Trophic Levels of Litter-dwelling Macrofauna Associated with Giant Knotweed Invasion. Ecosystems 2007, 10, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammon, M.A. The Diversity, Growth, and Fitness of the Invasive Plants Fallopia japonica (Japanese knotweed) and Fallopia xbohemica in the United States (Polygonaceae); University of Massachusetts Boston ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; 3361p. [Google Scholar]

- DIN 51731:1996-10; Testing of Solid Fuels—Compressed Untreated Wood—Requirements and Testing. German Institute of Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 1996.

- EU DD CENT/TS15149-1; Solid Biofuels. Methods for the Determination of Particle Size Distribution. Oscillating Screen Method Using Sieve Apertures of 3.15 mm and Above. Danish Standards Foundation: Kopenhagen, Denmark, 2006.

- LAND 43-2013; Emissions Standards for Fuel-Burning Plants. Lithuanian Environmental Ministry: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2013. (In Lithuanian)

- Žaltauskas, A.; Jasinskas, A.; Kryževičienė, A. Analysis of the Suitability Tall-Growing Plants for Cultivation and Use as a Fuel. In Perspective Sustainable Technological Processes in Agricultural Engineering: Proceedings of the International Conference; Lithuanian Institute of Agricultural Engineering: Raudondvaris, Lithuania, 2001; pp. 155–160. (In Lithuanian) [Google Scholar]

- Christoforou, E.; Fokaides, P.A. Environmental Assessment of Solid Biofuels. In Advances in Solid Biofuels. Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, S.; Monti, A. Life cycle assessment of different bioenergy production systems including perennial and annual crops. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 4868–4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tong, R.; Zhai, Q.; Lyu, G.; Li, Y. A Critical Review of Life Cycle Assessments on Bioenergy Technologies: Methodological Choices, Limitations, and Suggestions for Future Studies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18134-3:2023; Part 3: Moisture in General Analysis Sample. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 18847:2024; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Particle Density of Pellets and Briquettes. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ISO 17829:2025; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Length and Diameter of Pellets. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Jasinskas, A.; Streikus, D.; Vonžodas, T. Fibrous hemp (Felina 32, USO 31, Finola) and fibrous nettle processing and usage of pressed biofuel for energy purposes. Renew. Energy 2020, 149, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LST EN ISO 18122:2023; Solid biofuels—Determination of Ash Content. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- LST EN ISO 16948:2015; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen—Instrumental Methods. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- LST EN ISO 18125:2017; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Calorific Value. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- EN ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Guinée, J.B.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Kleijn, R.; de Koning, A.; van Oers, L.; Wegener Sleeswijk, A.; Suh, S.; Udo de Haes, H.A.; de Bruijn, H.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment. Operational Guide to the ISO Standards; I: LCA in Perspective. IIa: Guide. IIb: OperatiCastellonal Annex. III: Scientific Background; Ministries of The Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; p. 692.

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): Overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, B.; Chen, G.; Bowtell, L.; Mahmood, A.R. Assessment of densified fuel quality parameters: A case study for wheat straw pellet. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2023, 8, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado, M.P.P.; Gadelha, T.M.A.; Rodrigues, D.S.; Antonio, G.C.; Conti, A.C. Effect of torrefaction on the properties of briquettes produced from agricultural waste. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 21, 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Križan, P.; Matuš, M.; Šooš, L.; Beniak, J. Behavior of beech sawdust during densification in a solid biofuel. Energies 2015, 8, 6382–6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, S.J.; Fillerup, E. Briquetting characteristics of woody and herbaceous biomass blends: Impact on physical properties, chemical composition, and calorific value. Biofuel Bioprod. Biorefining 2020, 14, 1105–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djatkov, D.; Viskovic, M.; Golub, M.; Martinov, M. Corn cob pellets as a fuel in Serbia: Opportunities and constraints. In Proceedings of the Symposium “Actual Tasks on Agricultural Engineering”, Opatija, Croatia, 21–24 February 2017; pp. 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliyan, N.; Morey, V.R. Factors affecting strength and durability of densified biomass products. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakitis, A.; Nulle, I.; Ancans, D. Mechanical properties of composite biomass briquettes. In Environmental. Technology. Resources. Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific and Practical Conference; Curran Associates, Inc.: Rezekne, Latvia, 2011; Volume 1, p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov, A.; Kinzhibekova, A.; Prikhodko, E.; Karmanov, A.; Nurkina, S. Analysis of the Characteristics of Bio-Coal Briquettes from Agricultural and Coal Industry Waste. Energies 2023, 16, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werther, J.; Saenger, M.; Hartge, E.-U.; Ogada, T.; Siagi, Z. Combustion of Agricultural Residues. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2000, 26, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platace, R.; Adamovics, A.; Gulbe, I. Evaluation of factors influencing calorific value of reed canary grass spring and autumn yield. Engineering for rural development. In Proceedings of the 12th International Scientific Conference, Jelgava, Latvia, 23–24 May 2013; pp. 522–524. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, H.P.; Frandsen, F.J.; Dam-Johansen, K.; Baxter, L.L. The Implications of Chlorine-Associated Corrosion on the Operation of Biomass-Fired Boilers. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2000, 26, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramonova, K.; Ivanova, T.; Malik, A. Exploring the potential of invasive plant Sosnowsky’s hogweed for densified biofuels production. Ştiinţa Agricolă 2021, 2, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Krugly, E.; Mrtuzevičius, D.; Puida, E.; Buisinecičius, K.; Stasiulaitienė, I.; Radžiūnienė, I.; Minikauskas, A.; Kliučininkas, L. Characterization of gaseous- and particle-phase emissions from the combustion of biomass-residue-derived fuels in a small residential boiler. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 285057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippula, O.; Lamberg, H.; Leskinen, J.; Tissari, K.; Jokiniemi, J. Emissions and ash behavior in a 500 kW pellet boiler operated with various blends of woody biomass and peat. Fuel 2017, 202, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortelainen, M.; Jokiniemi, J.; Nuutinen, I.; Torvela, T.; Lamberg, H.; Karhunen, T.; Tissari, J.; Sippula, O. Ash behaviour and emission formation in a small-scale reciprocating grate combustion reactor operated with wood chips, reed canary grass and barley straw. Fuel 2015, 143, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutla, P.; Jevič, P.; Mazancova, J.; Plištil, D. Emission from energy herbs combustion. Res. Agric. Eng. 2005, 51, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strašil, Z.; Kara, J. Study of knotweed (Reynoutria) as possible phytomass resource for energy and industrial utilization. Res. Agric. Eng. 2010, 56, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petlickaitė, R.; Jasinskas, A.; Venslauskas, K.; Navickas, K.; Praspaliauskas, M.; Lemanas, E. Evaluation of Multi-Crop Biofuel Pellet Properties and the Life Cycle Assessment. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Želazna, A.; Kraszkiewicz, A.; Przywara, A.; Lagod, G.; Suchorab, Z.; Werle, S.; Ballester, J.; Nosek, R. Life cycle assessment of production of black locust logs and straw pellets for energy purposes. Environ. Prog. 2018, 38, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Month | Sosnowsky‘s Hogweed, t ha−1 | Giant Knotweed, t ha−1 | Reed, t ha−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| April | 0.92 | 1.47 | 1.11 |

| May | 6.48 | 2.40 | 3.41 |

| June | 7.15 | 6.15 | 6.78 |

| July | 8.96 | 6.40 | 7.26 |

| August | 4.85 | 3.26 | 4.32 |

| Plant Species | Pellet Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (d), mm | Length (l), mm | Volume (V), m3 | Mass (m), g | Density (ƍ), kg m−3 | |

| S.H. | 6.2 ± 1 0.22 | 23.6 ± 0.93 | (7.5 ± 0.59) × 10−7 | 0.7 ± 0.08 | 1145.6 ± 37.50 |

| G.K. | 6.1 ± 0.09 | 23.1 ± 0.84 | (6.8 ± 0.25) × 10−7 | 0.7 ± 0.04 | 1227.5 ± 39.82 |

| Reed | 6.1 ± 0.16 | 22.2 ± 0.68 | (5.8 ± 0.23) × 10−7 | 0.6 ± 0.05 | 1198.3 ± 31.34 |

| S.H. 25% 2 | 6.1 ± 0.20 | 17.5 ± 0.77 | (5.2 ± 0.43) × 10−7 | 0.6 ± 0.06 | 1124.8 ± 34.16 |

| S.H. 50% 2 | 6.1 ± 0.16 | 23 ± 0.82 | (6.7 ± 0.26) × 10−7 | 0.8 ± 0.02 | 1188.6 ± 34.82 |

| S.H. 75% 2 | 6.1 ± 0.06 | 15.9 ± 0.46 | (4.7 ± 0.39) × 10−7 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 1145.8 ± 42.01 |

| G.K. 25% 3 | 6.1 ± 0.11 | 21.5 ± 0.97 | (6.2 ± 0.34) × 10−7 | 0.8 ± 0.10 | 1236.5 ± 36.15 |

| G.K. 50% 3 | 6 ± 0.12 | 17.8 ± 0.58 | (5.1 ± 0.55) × 10−7 | 0.7 ± 0.06 | 1278.0 ± 35.10 |

| G.K. 75% 3 | 6.1 ± 0.21 | 22.7 ± 0.66 | (6.6 ± 0.61) × 10−7 | 0.8 ± 0.03 | 1205.9 ± 29.86 |

| Reed 25% 4 | 6 ± 0.08 | 19.5 ± 0.97 | (5.5 ± 0.48) × 10−7 | 0.7 ± 0.05 | 1221.6 ± 32.98 |

| Reed 50% 4 | 6.1 ± 0.19 | 20.1 ± 0.45 | (5.8 ± 0.36) × 10−7 | 0.7 ± 0.08 | 1154.1 ± 36.76 |

| Reed 75% 4 | 6 ± 0.17 | 22.2 ± 0.42 | (6.3 ± 0.72) × 10−7 | 0.8 ± 0.11 | 1341.0 ± 41.94 |

| Pinewood | 6.1 ± 0.13 | 30.7 ± 0.88 | (8.9 ± 0.83) × 10−7 | 1.1 ± 0.14 | 1182.5 ± 34.46 |

| Parameter | S.H. | G.K. | Reed | Pine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ash, % | 12.56 ± 1 0.66 | 5.74 ± 0.40 | 15.75 ± 0.05 | 4.03 ± 0.17 |

| HCV, MJ kg−1 | 17.93 ± 0.60 | 19.11 ± 0.64 | 17.62 ± 0.61 | 18.89 ± 1 |

| LCV, MJ kg−1 | 16.60 ± 0.65 | 17.78 ± 0.70 | 16.29 ± 0.67 | 17.56 ± 1 |

| C, % | 46.15 ± 1.87 | 48.38 ± 1.73 | 44.79 ± 1.37 | 49.26 ± 1.22 |

| N, % | 1.11 ± 0.31 | 1.45 ± 0.57 | 2.02 ± 0.40 | 0.83 ± 0.39 |

| H, % | 5.34 ± 0.67 | 5.75 ± 0.52 | 5.14 ± 0.45 | 5.86 ± 0.67 |

| S, % | <0.002 2 | 0.033 ± 0.01 | 0.047 ± 0.01 | 0.016 ± 0.01 |

| O, % | 34.84 ± 0.01 | 38.65 ± 0.01 | 32.25 ± 0.01 | 40.01 ± 0.01 |

| Cl, % | <0.005 2 | <0.005 2 | <0.005 2 | <0.005 2 |

| Parameter | S.H. 25% 2 | S.H. 50% 2 | S.H. 75% 2 | G.K. 25% 3 | G.K. 50% 3 | G.K. 75% 3 | Reed 25% 4 | Reed 50% 4 | Reed 75% 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ash, % | 6.16 ± 1 0.32 | 8.29 ± 0.41 | 10.42 ± 0.62 | 4.45 ± 0.39 | 4.88 ± 0.49 | 5.31 ± 0.51 | 6.96 ± 0.22 | 9.89 ± 0.47 | 12.82 ± 0.57 |

| HCV, MJ kg−1 | 18.65 ± 0.45 | 18.41 ± 0.62 | 18.16 ± 0.27 | 18.46 ± 0.47 | 19.00 ± 0.51 | 19.05 ± 0.39 | 18.57 ± 0.53 | 18.25 ± 0.48 | 17.93 ± 0.47 |

| LCV, MJ kg−1 | 17.32 ± 0.49 | 17.08 ± 0.57 | 16.84 ± 0.42 | 17.61 ± 0.55 | 17.67 ± 0.39 | 17.73 ± 0.44 | 17.24 ± 0.48 | 16.92 ± 0.39 | 16.61 ± 0.46 |

| C, % | 48.48 ± 1.56 | 47.70 ± 1.32 | 46.92 ± 1.22 | 49.04 ± 1.48 | 48.38 ± 1.13 | 48.59 ± 1.61 | 48.14 ± 1.55 | 47.06 ± 1.39 | 45.90 ± 1.68 |

| N, % | 0.90 ± 0.23 | 0.97 ± 0.17 | 1.04 ± 0.32 | 0.98 ± 0.22 | 1.13 ± 0.34 | 1.29 ± 0.41 | 1.12 ± 0.30 | 1.42 ± 0.31 | 1.72 ± 0.31 |

| H, % | 5.72 ± 0.69 | 5.59 ± 0.66 | 5.46 ± 0.51 | 5.83 ± 0.61 | 5.38 ± 0.78 | 5.77 ± 0.53 | 5.67 ± 0.68 | 5.49 ± 0.62 | 5.32 ± 0.48 |

| S, % | 0.012 ± 0.01 | 0.301 ± 0.01 | 0.005 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.302 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| O, % | 38.71 ± 0.01 | 37.34 ± 0.01 | 36.12 ± 0.01 | 39.66 ± 0.01 | 33.32 ± 0.01 | 38.98 ± 0.01 | 38.06 ± 0.01 | 36.12 ± 0.01 | 34.18 ± 0.01 |

| Cl, % | <0.005 5 | <0.005 5 | <0.005 5 | <0.005 5 | <0.005 5 | <0.005 5 | <0.005 5 | <0.005 5 | <0.005 5 |

| Plant Species | H2O, % | CO2, % | O2, % | CO, ppm | NOx, ppm | CxHy, ppm | SO2, ppm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.H. | 3.71 | 3.96 | 15.1 | 1022 | 119 | 29 | 0.17 |

| G.K. | 4.05 | 4.21 | 14.3 | 2667 | 249 | 164 | 3.68 |

| Reed | 3.56 | 4.03 | 15.0 | 253 | 174 | 16 | 4.16 |

| S.H. 25% + pine 75% | 4.07 | 4.54 | 14.4 | 256 | 79 | 13 | 0.83 |

| S.H. 50% + pine 50% | 3.79 | 4.28 | 14.8 | 402 | 96 | 18 | 0.21 |

| S.H. 75% + pine 25% | 3.84 | 3.89 | 15.1 | 861 | 105 | 36 | 0.72 |

| G.K. 25% + pine 75% | 3.91 | 4.15 | 14.7 | 143 | 59 | 13 | 1.91 |

| G.K. 50% + pine 50% | 4.22 | 4.51 | 14.4 | 195 | 111 | 14 | 1.08 |

| G.K. 75% + pine 25% | 3.93 | 4.12 | 14.6 | 1221 | 131 | 47 | 1.45 |

| Reed 25% + pine 75% | 3.96 | 4.31 | 14.7 | 174 | 113 | 18 | 2.33 |

| Reed 50% + pine 50% | 3.44 | 3.71 | 15.5 | 285 | 123 | 25 | 5.08 |

| Reed 75% + pine 25% | 3.83 | 4.02 | 15.0 | 232 | 152 | 18 | 8.52 |

| Pinewood pellets | 3.81 | 4.33 | 14.7 | 125 | 59 | 9 | 0.01 |

| Impact Category | Unit | Sosnowky’s Hogweed | Giant Knotweed | Reed | Pine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | kg Sbeq | 1.19 × 10−3 | 1.06 × 10−3 | 1.24 × 10−3 | 1.01 × 10−3 |

| ADF | MJ | 121.31 | 107.69 | 129.10 | 91.99 |

| GWP | kg CO2eq | 10.98 | 9.76 | 11.64 | 8.47 |

| ODT | kg CFC-11eq | 9.12 × 10−7 | 8.08 × 10−7 | 9.83 × 10−7 | 6.49 × 10−7 |

| HT | kg 1,4-DBeq | 56.36 | 50.18 | 58.61 | 47.33 |

| FWAE | kg 1,4-DBeq | 35.94 | 32.03 | 37.98 | 30.16 |

| MAE | kg 1,4-DBeq | 50,676.49 | 45,128.05 | 52,724.16 | 42,436.43 |

| TE | kg 1,4-DBeq | 6.08 × 10−2 | 5.42 × 10−2 | 6.33 × 10−2 | 5.08 × 10−2 |

| PO | kg C2H4eq | 3.72 × 10−3 | 3.32 × 10−3 | 3.93 × 10−3 | 2.94 × 10−3 |

| AP | kg SO2eq | 6.07 × 10−2 | 5.39 × 10−2 | 6.48 × 10−2 | 4.50 × 10−2 |

| EP | kg PO4eq | 3.43 × 10−2 | 3.05 × 10−2 | 3.61 × 10−2 | 2.73 × 10−2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gramauskas, G.; Jasinskas, A.; Vonžodas, T.; Lemanas, E.; Venslauskas, K. Investigations of the Use of Invasive Plant Biomass as an Additive in the Production of Wood-Based Pressed Biofuels, with a Focus on Their Quality and Environmental Impact. Plants 2026, 15, 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020303

Gramauskas G, Jasinskas A, Vonžodas T, Lemanas E, Venslauskas K. Investigations of the Use of Invasive Plant Biomass as an Additive in the Production of Wood-Based Pressed Biofuels, with a Focus on Their Quality and Environmental Impact. Plants. 2026; 15(2):303. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020303

Chicago/Turabian StyleGramauskas, Gvidas, Algirdas Jasinskas, Tomas Vonžodas, Egidijus Lemanas, and Kęstutis Venslauskas. 2026. "Investigations of the Use of Invasive Plant Biomass as an Additive in the Production of Wood-Based Pressed Biofuels, with a Focus on Their Quality and Environmental Impact" Plants 15, no. 2: 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020303

APA StyleGramauskas, G., Jasinskas, A., Vonžodas, T., Lemanas, E., & Venslauskas, K. (2026). Investigations of the Use of Invasive Plant Biomass as an Additive in the Production of Wood-Based Pressed Biofuels, with a Focus on Their Quality and Environmental Impact. Plants, 15(2), 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020303