Regulatory Roles of MYB Transcription Factors in Root Barrier Under Abiotic Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Classification and Diversification of MYB TFs

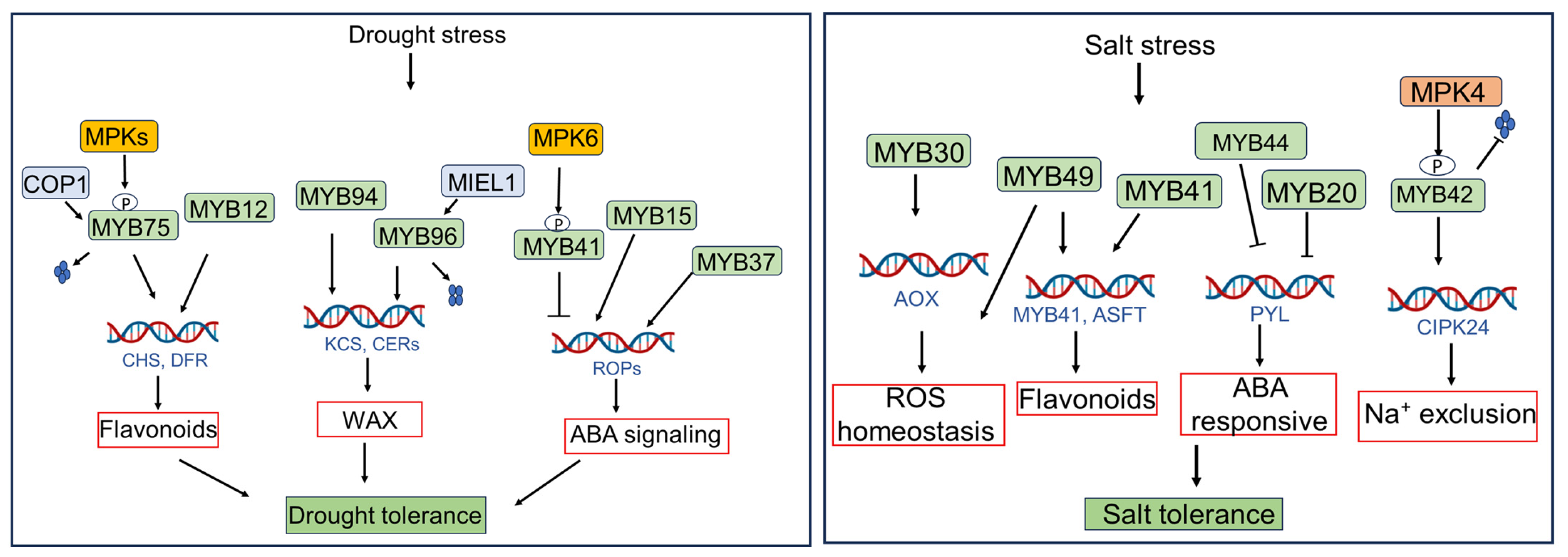

2.1. R2R3 MYBs in Stress-Induced Suberization

2.2. Hormonal Regulation of MYB-Mediated Stress Responses

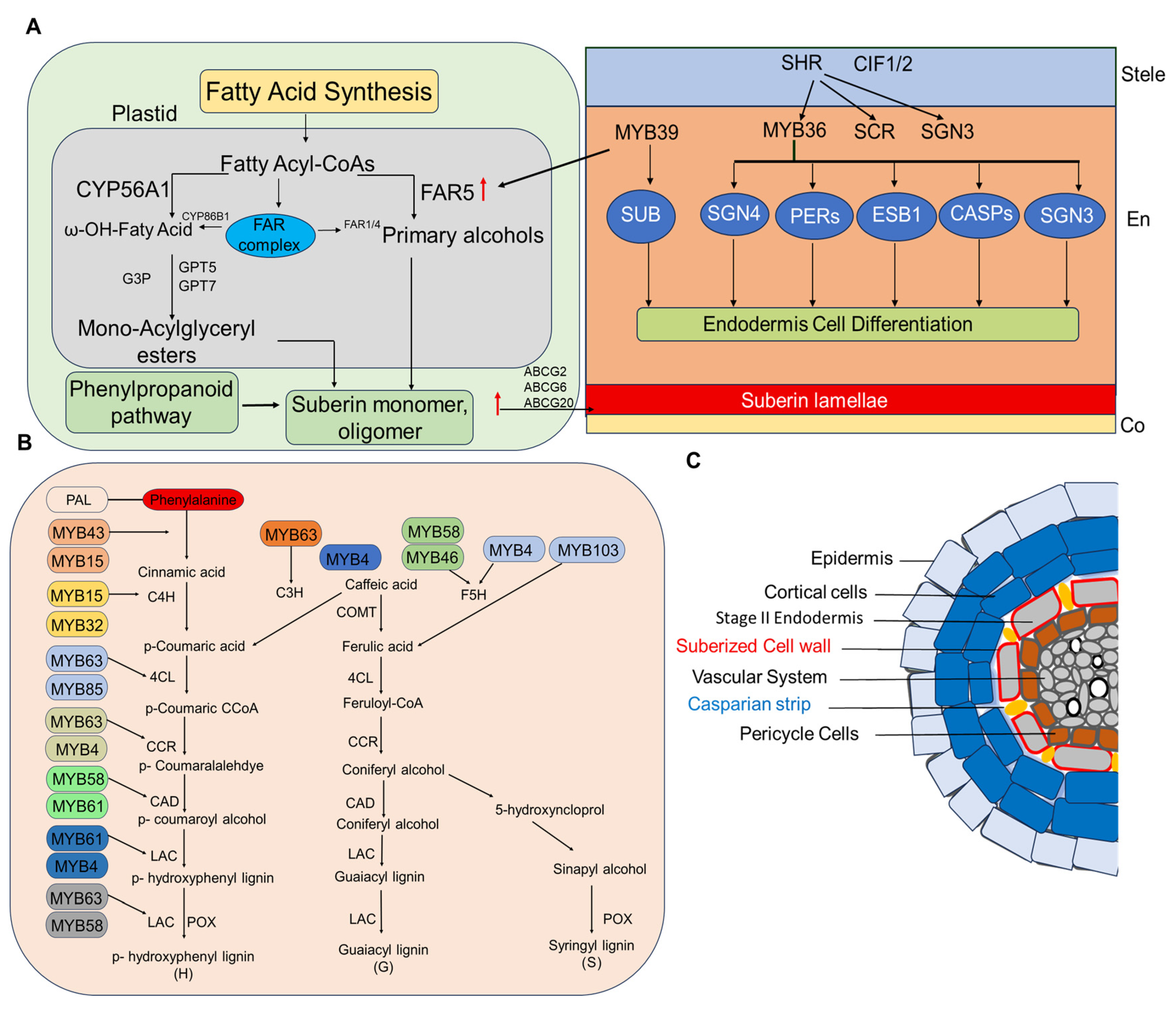

3. Suberin and Lignin Deposition as an Adaptive Barrier

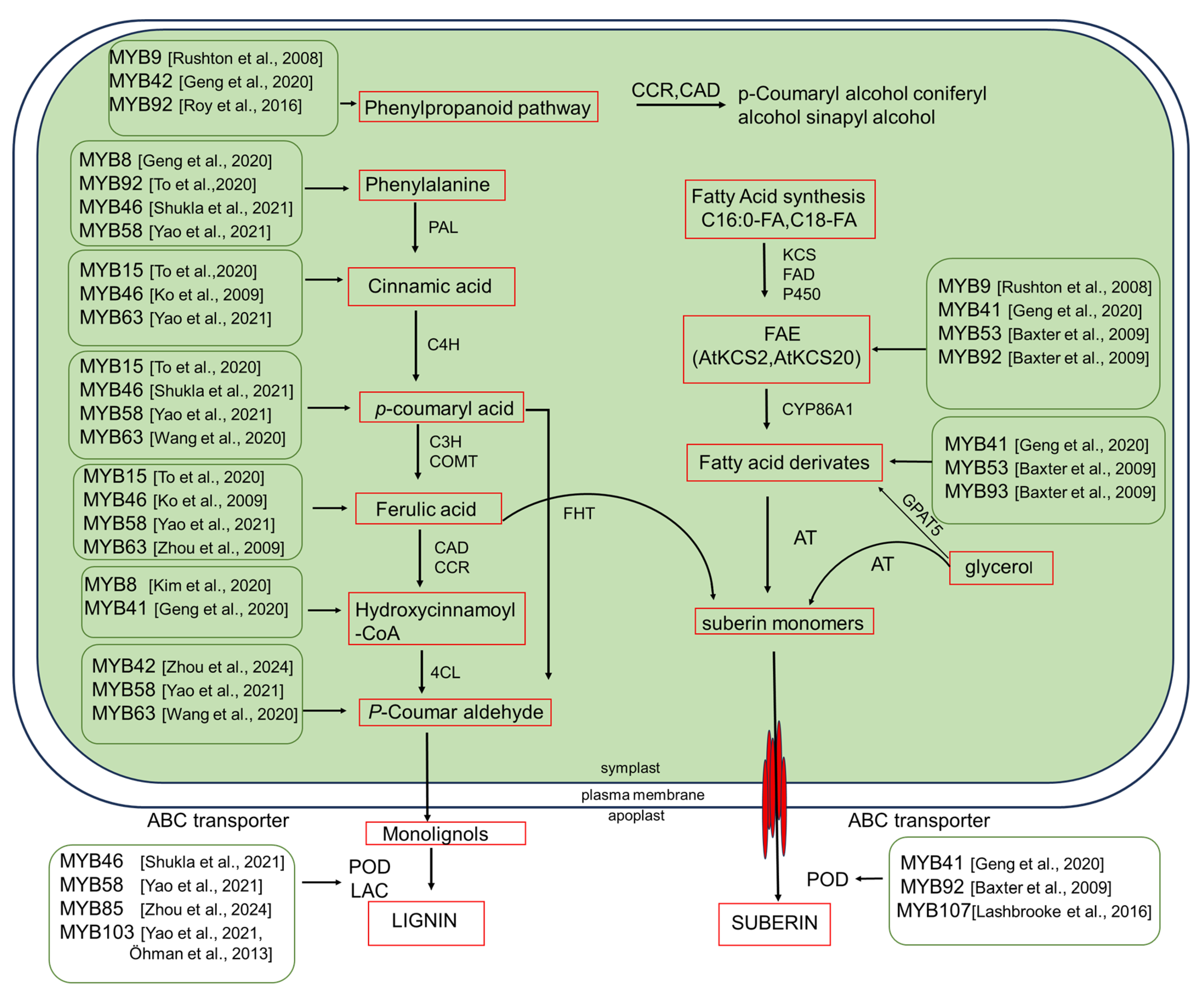

3.1. Biochemical Pathways in Suberin Biosynthesis

3.2. Lignin Deposition and Stress Responses

3.3. Transcriptional Regulation of Lignin

4. Stress-Induced MYB TFs in Arabidopsis Compared to Other Species

4.1. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)

4.2. Rice (Oryza sativa)

4.3. Conserved vs. Species-Specific Mechanisms

5. Cross-Talk Between Suberin and Lignin Pathways

5.1. Shared Biochemical Precursors and Metabolic Challenges

5.2. MYBs as Decision Nodes Balancing Lignin and Suberin

5.3. Compensatory Regulation: Loss of One Barrier Amplifies the Other

6. Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baxter, I.; Hosmani, P.S.; Rus, A.; Lahner, B.; Borevitz, J.O.; Muthukumar, B.; Mickelbart, M.V.; Schreiber, L.; Franke, R.B.; Salt, D.E. Root suberin forms an extracellular barrier that affects water relations and mineral nutrition in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberon, M.; Geldner, N. Radial transport of nutrients: The plant root as a polarized epithelium. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberon, M.; Vermeer, J.E.M.; De Bellis, D.; Wang, P.; Naseer, S.; Andersen, T.G.; Humbel, B.M.; Nawrath, C.; Takano, J.; Salt, D.E. Adaptation of root function by nutrient-induced plasticity of endodermal differentiation. Cell 2016, 164, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblas, V.G.; Geldner, N.; Barberon, M. The endodermis, a tightly controlled barrier for nutrients. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Takatsuka, H.; Takahashi, N.; Kurata, R.; Fukao, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Ito, M.; Umeda, M. Arabidopsis R1R2R3-Myb proteins are essential for inhibiting cell division in response to DNA damage. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.H. Introduction to transcription factor structure and function. In Plant Transcription Factors; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, H.; Fedyuk, V.; Wang, C.; Wu, S.; Aharoni, A. SUBERMAN regulates developmental suberization of the Arabidopsis root endodermis. Plant J. 2020, 102, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, S.; Fujita, S.; Moretti, A.; Hohmann, U.; Doblas, V.G.; Ma, Y.; Pfister, A.; Brandt, B.; Geldner, N.; Hothorn, M. Molecular mechanism for the recognition of sequence-divergent CIF peptides by the plant receptor kinases GSO1/SGN3 and GSO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 2693–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-González, I.; Reyt, G.; Flis, P.; Custódio, V.; Gopaulchan, D.; Bakhoum, N.; Dew, T.P.; Suresh, K.; Franke, R.B.; Dangl, J.L. Coordination between microbiota and root endodermis supports plant mineral nutrient homeostasis. Science 2021, 371, eabd0695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, V.; Han, J.-P.; Cléard, F.; Lefebvre-Legendre, L.; Gully, K.; Flis, P.; Berhin, A.; Andersen, T.G.; Salt, D.E.; Nawrath, C. Suberin plasticity to developmental and exogenous cues is regulated by a set of MYB transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2101730118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S. Function of MYB domain transcription factors in abiotic stress and epigenetic control of stress response in plant genome. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016, 11, e1117723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambawat, S.; Sharma, P.; Yadav, N.R.; Yadav, R.C. MYB transcription factor genes as regulators for plant responses: An overview. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2013, 19, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldner, N. The endodermis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 531–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosma, D.K.; Murmu, J.; Razeq, F.M.; Santos, P.; Bourgault, R.; Molina, I.; Rowland, O. At MYB 41 activates ectopic suberin synthesis and assembly in multiple plant species and cell types. Plant J. 2014, 80, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Wang, C.-M.; Gao, L.; Cui, Y.-N.; Yang, H.-L.; de Silva, N.D.G.; Ma, Q.; Bao, A.-K.; Flowers, T.J.; Rowland, O. Aliphatic suberin confers salt tolerance to Arabidopsis by limiting Na+ influx, K+ efflux and water backflow. Plant Soil 2020, 448, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornalé, S.; Shi, X.; Chai, C.; Encina, A.; Irar, S.; Capellades, M.; Fuguet, E.; Torres, J.L.; Rovira, P.; Puigdomenech, P. ZmMYB31 directly represses maize lignin genes and redirects the phenylpropanoid metabolic flux. Plant J. 2010, 64, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, D.; Demedts, B.; Kumar, M.; Gerber, L.; Gorzsás, A.; Goeminne, G.; Hedenström, M.; Ellis, B.; Boerjan, W.; Sundberg, B. MYB 103 is required for FERULATE-5-HYDROXYLASE expression and syringyl lignin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis stems. Plant J. 2013, 73, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, P.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, C.; Wu, J.; Cao, Y.; Fu, C.; Han, X.; He, H.; Zhao, Q. MYB20, MYB42, MYB43, and MYB85 regulate phenylalanine and lignin biosynthesis during secondary cell wall formation. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lee, C.; Zhong, R.; Ye, Z.-H. MYB58 and MYB63 are transcriptional activators of the lignin biosynthetic pathway during secondary cell wall formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Liu, P.; Wang, C.; Wu, S.; Dong, C.; Lin, Q.; Sun, W.; Huang, B.; Xu, M.; Tauqeer, A. Transcriptional networks regulating suberin and lignin in endodermis link development and ABA response. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, L.M.; Sparks, E.E.; Moreno-Risueno, M.A.; Petricka, J.J.; Benfey, P.N. MYB36 regulates the transition from proliferation to differentiation in the Arabidopsis root. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 12099–12104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Richardson, E.A.; Ye, Z.-H. The MYB46 transcription factor is a direct target of SND1 and regulates secondary wall biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2776–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiono, K.; Yoshikawa, M.; Kreszies, T.; Yamada, S.; Hojo, Y.; Matsuura, T.; Mori, I.C.; Schreiber, L.; Yoshioka, T. Abscisic acid is required for exodermal suberization to form a barrier to radial oxygen loss in the adventitious roots of rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 2022, 233, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonbol, F.-M.; Fornalé, S.; Capellades, M.; Encina, A.; Touriño, S.; Torres, J.-L.; Rovira, P.; Ruel, K.; Puigdomenech, P.; Rigau, J. The maize Zm MYB42 represses the phenylpropanoid pathway and affects the cell wall structure, composition and degradability in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 70, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillo, E.H.; Kimotho, R.N.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, P. Transcription factors associated with abiotic and biotic stress tolerance and their potential for crops improvement. Genes 2019, 10, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreszies, T.; Shellakkutti, N.; Osthoff, A.; Yu, P.; Baldauf, J.A.; Zeisler-Diehl, V.V.; Ranathunge, K.; Hochholdinger, F.; Schreiber, L. Osmotic stress enhances suberization of apoplastic barriers in barley seminal roots: Analysis of chemical, transcriptomic and physiological responses. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Liu, T.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X. Plant root suberin: A layer of defence against biotic and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1056008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta Ogorek, L.L.; Jiménez, J.d.l.C.; Visser, E.J.W.; Takahashi, H.; Nakazono, M.; Shabala, S.; Pedersen, O. Outer apoplastic barriers in roots: Prospects for abiotic stress tolerance. Funct. Plant Biol. 2023, 51, FP23133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Navarro, J.D.; Díaz-Rueda, P.; Rivero-Núñez, C.M.; Brumós, J.; Rubio-Casal, A.E.; de Cires, A.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Rosales, M.A. Chloride nutrition improves drought resistance by enhancing water deficit avoidance and tolerance mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 5246–5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.S.; Sohn, H.B.; Noh, K.; Jung, C.; An, J.H.; Donovan, C.M.; Somers, D.A.; Kim, D.I.; Jeong, S.-C.; Kim, C.-G. Expression of the Arabidopsis AtMYB44 gene confers drought/salt-stress tolerance in transgenic soybean. Mol. Breed. 2012, 29, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, T.; Borghi, M.; Wang, P.; Danku, J.M.C.; Kalmbach, L.; Hosmani, P.S.; Naseer, S.; Fujiwara, T.; Geldner, N.; Salt, D.E. The MYB36 transcription factor orchestrates Casparian strip formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10533–10538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisson, F.; Li-Beisson, Y.; Pollard, M. Solving the puzzles of cutin and suberin polymer biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfer, R.; Briesen, I.; Beck, M.; Pinot, F.; Schreiber, L.; Franke, R. The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 CYP86A1 encodes a fatty acid ω-hydroxylase involved in suberin monomer biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2347–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V.; Molina, I.; Ranathunge, K.; Castillo, I.Q.; Rothstein, S.J.; Reed, J.W. ABCG transporters are required for suberin and pollen wall extracellular barriers in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3569–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, P.J.; Bokowiec, M.T.; Laudeman, T.W.; Brannock, J.F.; Chen, X.; Timko, M.P. TOBFAC: The database of tobacco transcription factors. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, A.; Joubès, J.; Thueux, J.; Kazaz, S.; Lepiniec, L.; Baud, S. AtMYB92 enhances fatty acid synthesis and suberin deposition in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant J. 2020, 103, 660–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Feng, K.; Xie, M.; Barros, J.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Tuskan, G.A.; Muchero, W.; Chen, J.-G. Phylogenetic occurrence of the phenylpropanoid pathway and lignin biosynthesis in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 704697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lam, P.Y.; Lee, M.-H.; Jeon, H.S.; Tobimatsu, Y.; Park, O.K. The Arabidopsis R2R3 MYB transcription factor MYB15 is a key regulator of lignin biosynthesis in effector-triggered immunity. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 583153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Li, P.; Li, H.; Xu, C.; Cohen, H.; Aharoni, A.; Wu, S. Developmental programs interact with abscisic acid to coordinate root suberization in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2020, 104, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.; Guo, Y. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J. Genet. Genom. 2024, 51, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashbrooke, J.; Cohen, H.; Levy-Samocha, D.; Tzfadia, O.; Panizel, I.; Zeisler, V.; Massalha, H.; Stern, A.; Trainotti, L.; Schreiber, L. MYB107 and MYB9 homologs regulate suberin deposition in angiosperms. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 2097–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, O.; Geldner, N. The making of suberin. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 848–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legay, S.; Guerriero, G.; André, C.; Guignard, C.; Cocco, E.; Charton, S.; Boutry, M.; Rowland, O.; Hausman, J.F. MdMyb93 is a regulator of suberin deposition in russeted apple fruit skins. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, M.; Hou, G.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Cai, Y.; Kai, G.; Liu, C.-J. The MYB107 transcription factor positively regulates suberin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capote, T.; Barbosa, P.; Usié, A.; Ramos, A.M.; Inácio, V.; Ordás, R.; Gonçalves, S.; Morais-Cecílio, L. ChIP-Seq reveals that QsMYB1 directly targets genes involved in lignin and suberin biosynthesis pathways in cork oak (Quercus suber). BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, S.; Gautam, K.; Iglesias-Moya, J.; Martínez, C.; Jamilena, M. Crosstalk between ethylene, jasmonate and ABA in response to salt stress during germination and early plant growth in Cucurbita pepo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Prusky, D.; Bi, Y. MYB24, MYB144, and MYB168 positively regulate suberin biosynthesis at potato tuber wounds during healing. Plant J. 2024, 119, 1239–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, D.; Chen, P.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Xie, Y.; Niu, C.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X. MdMYB88 and MdMYB124 enhance drought tolerance by modulating root vessels and cell walls in apple. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 1296–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Nakashima, J.; Chen, F.; Yin, Y.; Fu, C.; Yun, J.; Shao, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Dixon, R.A. Laccase is necessary and nonredundant with peroxidase for lignin polymerization during vascular development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 3976–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Yu, Q.; Gu, X.; Xu, C.; Qi, S.; Wang, H.; Zhong, F.; Baskin, T.I.; Rahman, A.; Wu, S. Construction of a functional casparian strip in non-endodermal lineages is orchestrated by two parallel signaling systems in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 2777–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.J.; Baek, D.; Cho, H.M.; Lee, S.H.; Jin, B.J.; Yun, D.-J.; Hong, Y.-S.; Kim, M.C. Lignin biosynthesis genes play critical roles in the adaptation of Arabidopsis plants to high-salt stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2019, 14, 1625697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Linker, R.; Gepstein, S.; Tanimoto, E.; Yamamoto, R.; Neumann, P.M. Progressive inhibition by water deficit of cell wall extensibility and growth along the elongation zone of maize roots is related to increased lignin metabolism and progressive stelar accumulation of wall phenolics. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.E.; Kim, T.H.; Shim, J.S.; Bang, S.W.; Yoon, H.B.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Oh, S.-J.; Seo, J.S.; Kim, J.-K. Rice NAC17 transcription factor enhances drought tolerance by modulating lignin accumulation. Plant Sci. 2022, 323, 111404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Qi, H. Drought-induced ABA, H2O2 and JA positively regulate CmCAD genes and lignin synthesis in melon stems. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Gupta, S.K.; Dwivedi, V.; Chattopadhyay, D. Lignin deposition in chickpea root xylem under drought. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1754621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Wang, Y.; Xie, H.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, J.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Ding, Z. Drought stress triggers proteomic changes involving lignin, flavonoids and fatty acids in tea plants. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, M.; Wang, X.; Yin, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Song, J.; Wang, X. Grapevine VlbZIP30 improves drought resistance by directly activating VvNAC17 and promoting lignin biosynthesis through the regulation of three peroxidase genes. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.J.; Lee, Z.; Kim, S.; Jeong, E.; Shim, J.S. Modulation of lignin biosynthesis for drought tolerance in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1116426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.-H. Lignin biosynthesis and its diversified roles in disease resistance. Genes 2024, 15, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, S.W.; Choi, S.; Jin, X.; Jung, S.E.; Choi, J.W.; Seo, J.S.; Kim, J.K. Transcriptional activation of rice CINNAMOYL-CoA REDUCTASE 10 by OsNAC5, contributes to drought tolerance by modulating lignin accumulation in roots. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zhang, C.; Guo, X.; Li, H.; Lu, H. MYB transcription factors and its regulation in secondary cell wall formation and lignin biosynthesis during xylem development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Z.; Wu, M.; Chao, D.; Wei, Q.; Xin, Y.; Li, L.; Ming, Z.; Xia, J. Three OsMYB36 members redundantly regulate Casparian strip formation at the root endodermis. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 2948–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantó-Pastor, A.; Kajala, K.; Shaar-Moshe, L.; Manzano, C.; Timilsena, P.; De Bellis, D.; Gray, S.; Holbein, J.; Yang, H.; Mohammad, S. A suberized exodermis is required for tomato drought tolerance. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, L.; Buti, S.; Artur, M.A.S.; Kluck, R.M.C.; Cantó-Pastor, A.; Brady, S.M.; Kajala, K. Transcription factors SlMYB41, SlMYB92, and SlWRKY71 regulate gene expression in the tomato exodermis. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 6472–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberon, M. The endodermis as a checkpoint for nutrients. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyt, G.; Ramakrishna, P.; Salas-González, I.; Fujita, S.; Love, A.; Tiemessen, D.; Lapierre, C.; Morreel, K.; Calvo-Polanco, M.; Flis, P. Two chemically distinct root lignin barriers control solute and water balance. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, K.; Luo, T.; Zhang, B.; Yu, J.; Ma, D.; Sun, X.; Zheng, H.; Xin, B.; Xia, J. Four MYB transcription factors regulate suberization and nonlocalized lignification at the root endodermis in rice. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koae278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, X.; Tian, B.; Tian, T.; Meng, Y.; Liu, F. Analysis of the MYB gene family in tartary buckwheat and functional investigation of FtPinG0005108900. 01 in response to drought. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Domergue, F.; Vishwanath, S.J.; Joubès, J.; Ono, J.; Lee, J.A.; Bourdon, M.; Alhattab, R.; Lowe, C.; Pascal, S.; Lessire, R. Three Arabidopsis fatty acyl-coenzyme A reductases, FAR1, FAR4, and FAR5, generate primary fatty alcohols associated with suberin deposition. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1539–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, J.C.; Rencoret, J.; Gutiérrez, A.; Elder, T.; Kim, H.; Ralph, J. Lignin monomers from beyond the canonical monolignol biosynthetic pathway: Another brick in the wall. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 4997–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, S.J.; Delude, C.; Domergue, F.; Rowland, O. Suberin: Biosynthesis, regulation, and polymer assembly of a protective extracellular barrier. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grima-Pettenati, J.; Soler, M.; Camargo, E.L.O.; Wang, H. Transcriptional regulation of the lignin biosynthetic pathway revisited: New players and insights. In Advances in botanical research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 61, pp. 173–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J.H.; Kim, W.C.; Han, K.H. Ectopic expression of MYB46 identifies transcriptional regulatory genes involved in secondary wall biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009, 60, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M.L.; Schuetz, M.; Unda, F.; Smith, R.A.; Sibout, R.; Hoffmann, N.J.; Wong, D.C.J.; Castellarin, S.D.; Mansfield, S.D.; Samuels, L. Dwarfism of high-monolignol Arabidopsis plants is rescued by ectopic LACCASE overexpression. Plant Direct 2020, 4, e00265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapek, C.; Sparks, E.E.; Marhavy, P.; Taylor, I.; Andersen, T.G.; Hennacy, J.H.; Geldner, N.; Benfey, P.N. Minimum requirements for changing and maintaining endodermis cell identity in the Arabidopsis root. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakoby, M.J.; Falkenhan, D.; Mader, M.T.; Brininstool, G.; Wischnitzki, E.; Platz, N.; Hudson, A.; Hulskamp, M.; Larkin, J.; Schnittger, A. Transcriptional profiling of mature Arabidopsis trichomes reveals that NOECK encodes the MIXTA-like transcriptional regulator MYB106. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1583–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enstone, D.E.; Peterson, C.A.; Ma, F. Root endodermis and exodermis: Structure, function, and responses to the environment. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2002, 21, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, M.; Udagawa, M.; Nishikubo, N.; Horiguchi, G.; Yamaguchi, M.; Ito, J.; Mimura, T.; Fukuda, H.; Demura, T. Transcription switches for protoxylem and metaxylem vessel formation. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 1855–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raes, J.; Rohde, A.; Christensen, J.H.; Van de Peer, Y.; Boerjan, W. Genome-wide characterization of the lignification toolbox in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 1051–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-C.; Kim, J.-Y.; Ko, J.-H.; Kang, H.; Han, K.-H. Identification of direct targets of transcription factor MYB46 provides insights into the transcriptional regulation of secondary wall biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2014, 85, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wen, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, L.; Du, H. Evolution and functional diversification of R2R3-MYB transcription factors in plants. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Dong, C.; Wu, Y.; Fu, S.; Tauqeer, A.; Gu, X.; Li, Q.; Niu, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, X. The JA-to-ABA signaling relay promotes lignin deposition for wound healing in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, D.; Yan, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhao, P. Genome-wide analysis of transcription factor R2R3-MYB gene family and gene expression profiles during anthocyanin synthesis in common walnut (Juglans regia L.). Genes 2024, 15, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phukela, B.; Leonard, H.; Sapir, Y. In silico analysis of R2R3-MYB transcription factors in the basal eudicot model, Aquilegia coerulea. 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Zhang, J.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Tuskan, G.A.; Chen, J.-G.; Muchero, W. Regulation of lignin biosynthesis and its role in growth-defense tradeoffs. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Kong, W.; Wong, G.; Fu, L.; Peng, R.; Li, Z.; Yao, Q. AtMYB12 regulates flavonoids accumulation and abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2016, 291, 1545–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakabayashi, R.; Yonekura-Sakakibara, K.; Urano, K.; Suzuki, M.; Yamada, Y.; Nishizawa, T.; Matsuda, F.; Kojima, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Shinozaki, K. Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J. 2014, 77, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, I.; Li-Beisson, Y.; Beisson, F.; Ohlrogge, J.B.; Pollard, M. Identification of an Arabidopsis feruloyl-coenzyme A transferase required for suberin synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Li, S.; An, X.; Liu, X.; Qin, H.; Wang, D. Transgenic expression of MYB15 confers enhanced sensitivity to abscisic acid and improved drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Genet. Genom. 2009, 36, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-T.; Wu, Z.; Lu, K.; Bi, C.; Liang, S.; Wang, X.-F.; Zhang, D.-P. Overexpression of the MYB37 transcription factor enhances abscisic acid sensitivity, and improves both drought tolerance and seed productivity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 90, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.H.; Yoo, K.S.; Hyoung, S.; Nguyen, H.T.K.; Kim, Y.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Ok, S.H.; Yoo, S.D.; Shin, J.S. An Arabidopsis R2R3-MYB transcription factor, AtMYB20, negatively regulates type 2C serine/threonine protein phosphatases to enhance salt tolerance. Febs Lett. 2013, 587, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Ju, Q.; Li, W.; Lü, S.; Tran, L.S.P.; Xu, J. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor AtMYB49 modulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis by modulating the cuticle formation and antioxidant defence. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 1925–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Q.; Li, S.; Zheng, Y.; Duan, H.; Xiao, F.; Zhuang, Y.; He, J.; Wu, G.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, H. SUMOylation of MYB30 enhances salt tolerance by elevating alternative respiration via transcriptionally upregulating AOX1a in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2020, 102, 1157–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Li, Y. E2 conjugases UBC1 and UBC2 regulate MYB42-mediated SOS pathway in response to salt stress in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genes | Expression | Phenotypes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| MYB103 | Lignifying Tissues(Stem, leaves and flowers) | Enhanced lignification | [16,17] |

| MYB31 MYB42 | Lignifying tissues(Stem, leaves and flowers) | Reduced lignification | [18] |

| MYB58 MYB63 | Secondary differentiation | Abnormal lignification | [19] |

| MYB85 MYB20 MYB42 MYB43 | Lignifying tissue(Stem, leaf, root and flower) | Enhanced lignification | [18] |

| MYB74 | Suberin deposition | Enhanced suberization | [20] |

| MYB36 | Suberized tissues(Root endodermis) | Enhanced suberization | [21] |

| MYB46/85 | Lignifying Tissues (Root and stem) | Enhanced Lignification | [22] |

| Species | Treatment | Lignin Accumulation | Tissues | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 1 µM ABA | Increased | Roots (Inner metaxylem position and cortical cell) | [3,39] |

| Zea mays | PEG6000 | Increased | Root (xylem fiber) | [52] |

| Oryza sativa | 16%PEG6000 | Increased | Stem and roots | [53] |

| Cucumis melo | 8% PEG6000 | Reduced | Stem and roots | [54] |

| Cicer arietinum | Holding water | Increased | Roots (meta xylem and protoxylem) | [55] |

| Camellia sinensis | Holding water | Increased | Non-identified | [56] |

| Malus domestica | Holding water | Increased | Roots | [48] |

| Vitis vinifera | PEG6000 | Increased | Secondary xylem | [57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Touqeer, A.; Yuanbo, H.; Li, M.; Wu, S. Regulatory Roles of MYB Transcription Factors in Root Barrier Under Abiotic Stress. Plants 2026, 15, 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020275

Touqeer A, Yuanbo H, Li M, Wu S. Regulatory Roles of MYB Transcription Factors in Root Barrier Under Abiotic Stress. Plants. 2026; 15(2):275. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020275

Chicago/Turabian StyleTouqeer, Arfa, Huang Yuanbo, Meng Li, and Shuang Wu. 2026. "Regulatory Roles of MYB Transcription Factors in Root Barrier Under Abiotic Stress" Plants 15, no. 2: 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020275

APA StyleTouqeer, A., Yuanbo, H., Li, M., & Wu, S. (2026). Regulatory Roles of MYB Transcription Factors in Root Barrier Under Abiotic Stress. Plants, 15(2), 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020275