Integrated Evaluation of Alkaline Tolerance in Soybean: Linking Germplasm Screening with Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

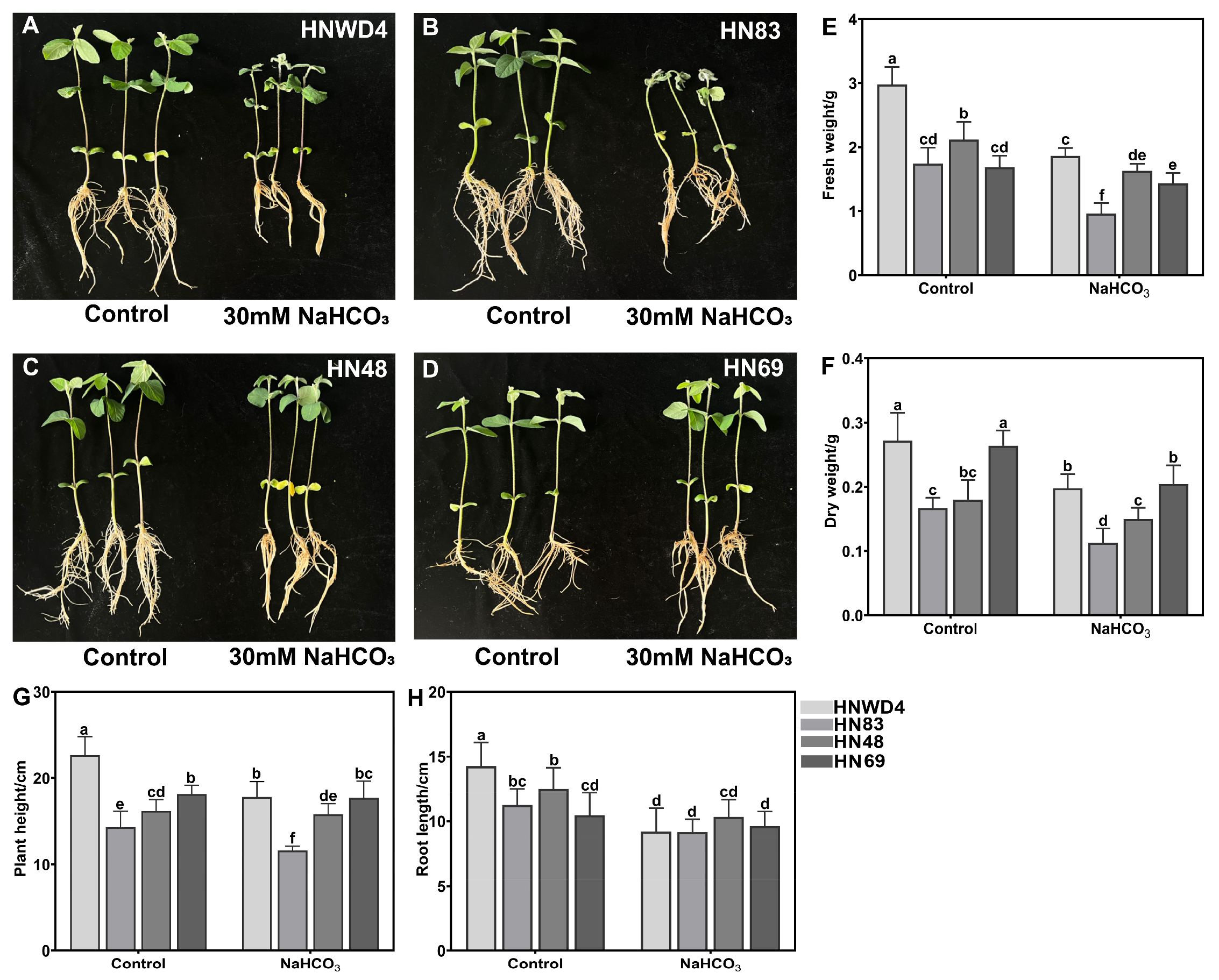

2.1. Assessment of Morphological Alterations Under Alkali Stress

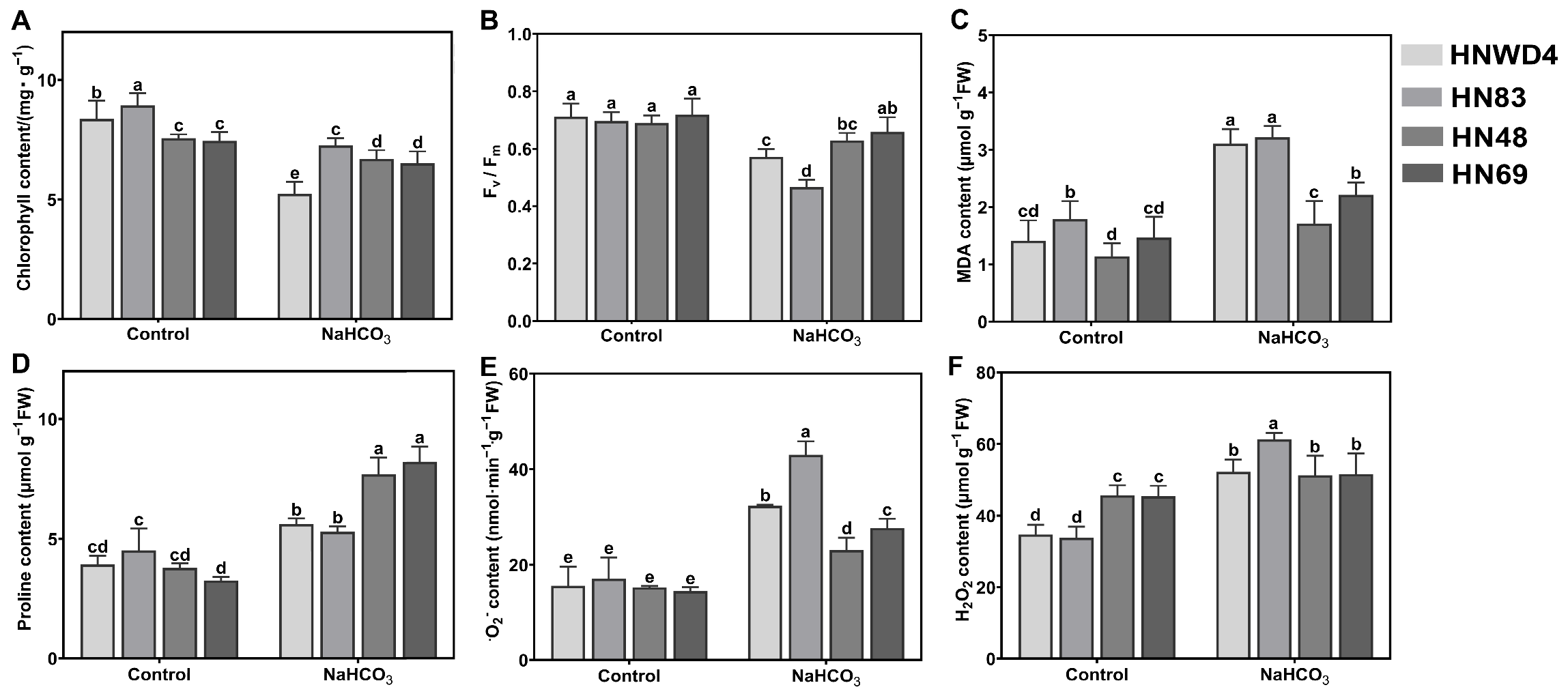

2.2. Measurement of Physiological Attributes in Soybean Seedlings Under Alkali Stress

2.3. Measurement of Stress Indicators (MDA, H2O2, O2−, and Proline Contents)

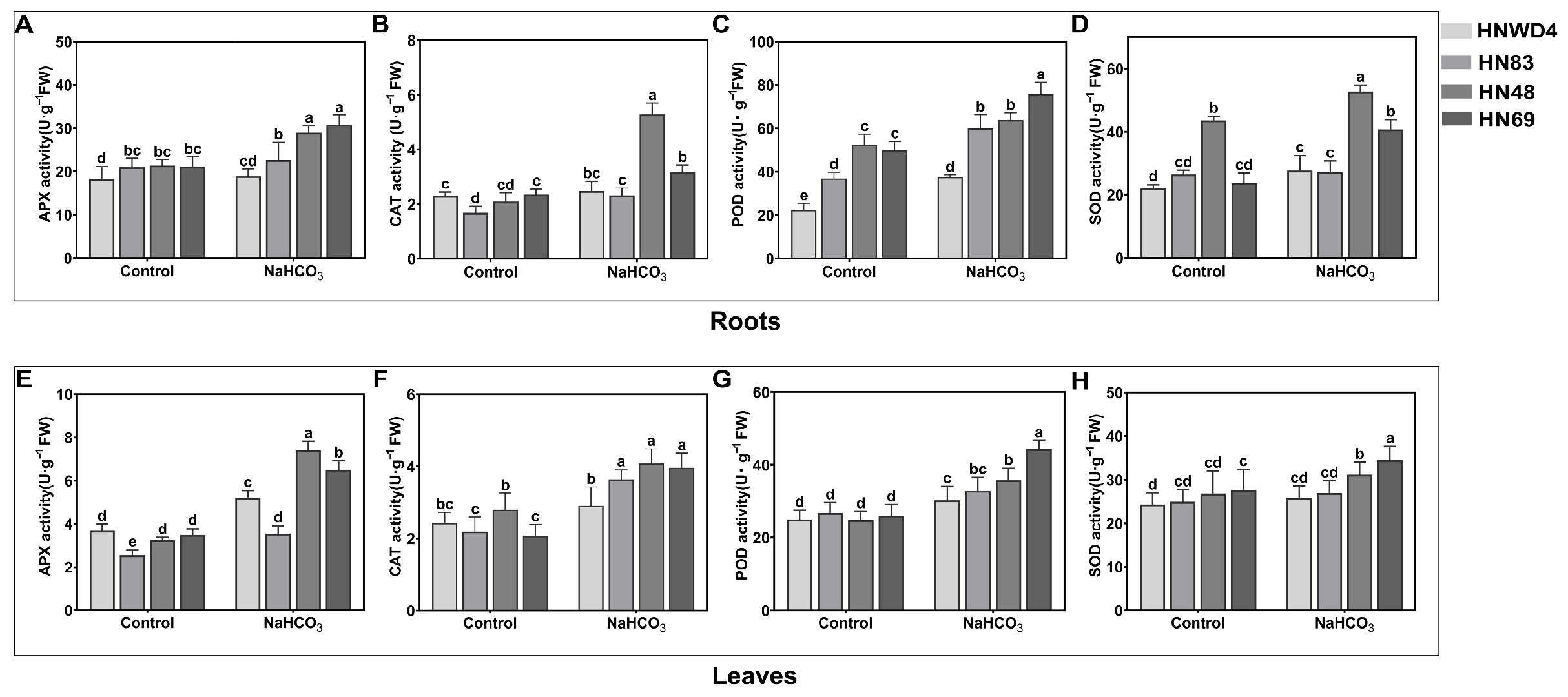

2.4. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities of Soybean Seedlings (HN48, HN69, HN83, and HNWD4) Under Alkaline Stress

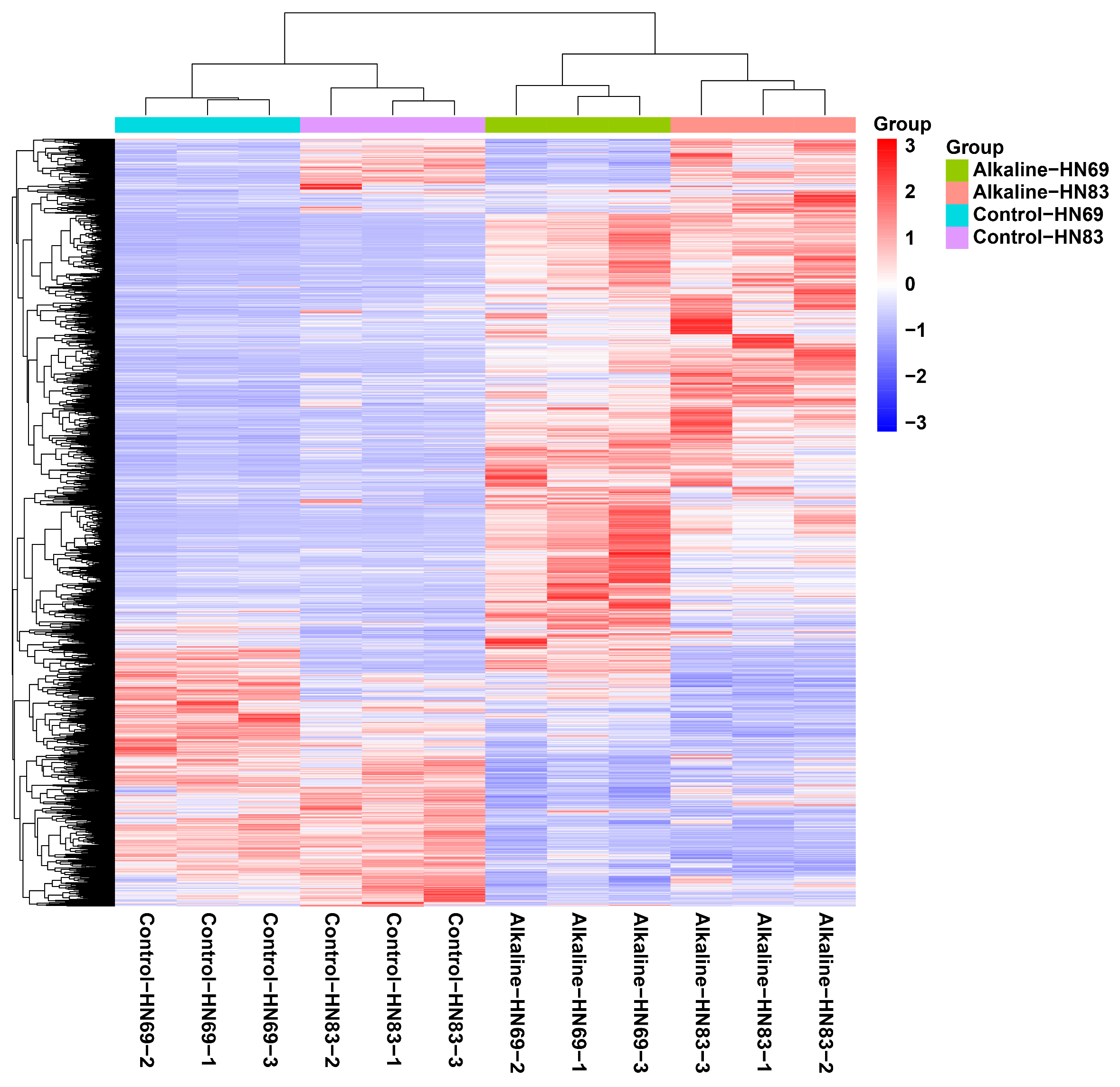

2.5. Differential Transcriptional Analysis of Soybean Seedlings (HN69 and HN83) Under Alkaline Stress

2.5.1. Functional Annotation and Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

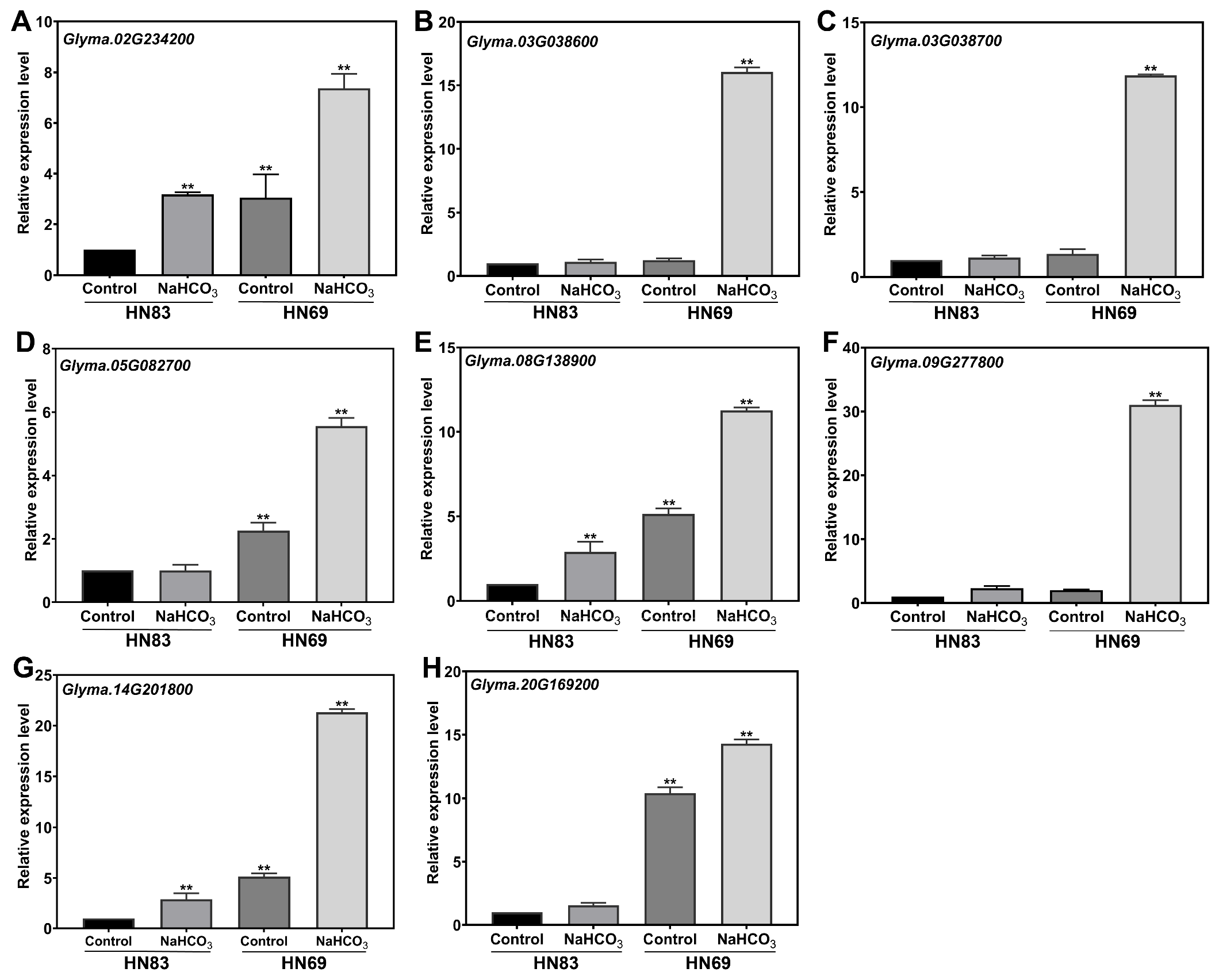

2.5.2. Gene Expression Analysis Using qRT-PCR (Quantitative Real-Time PCR)

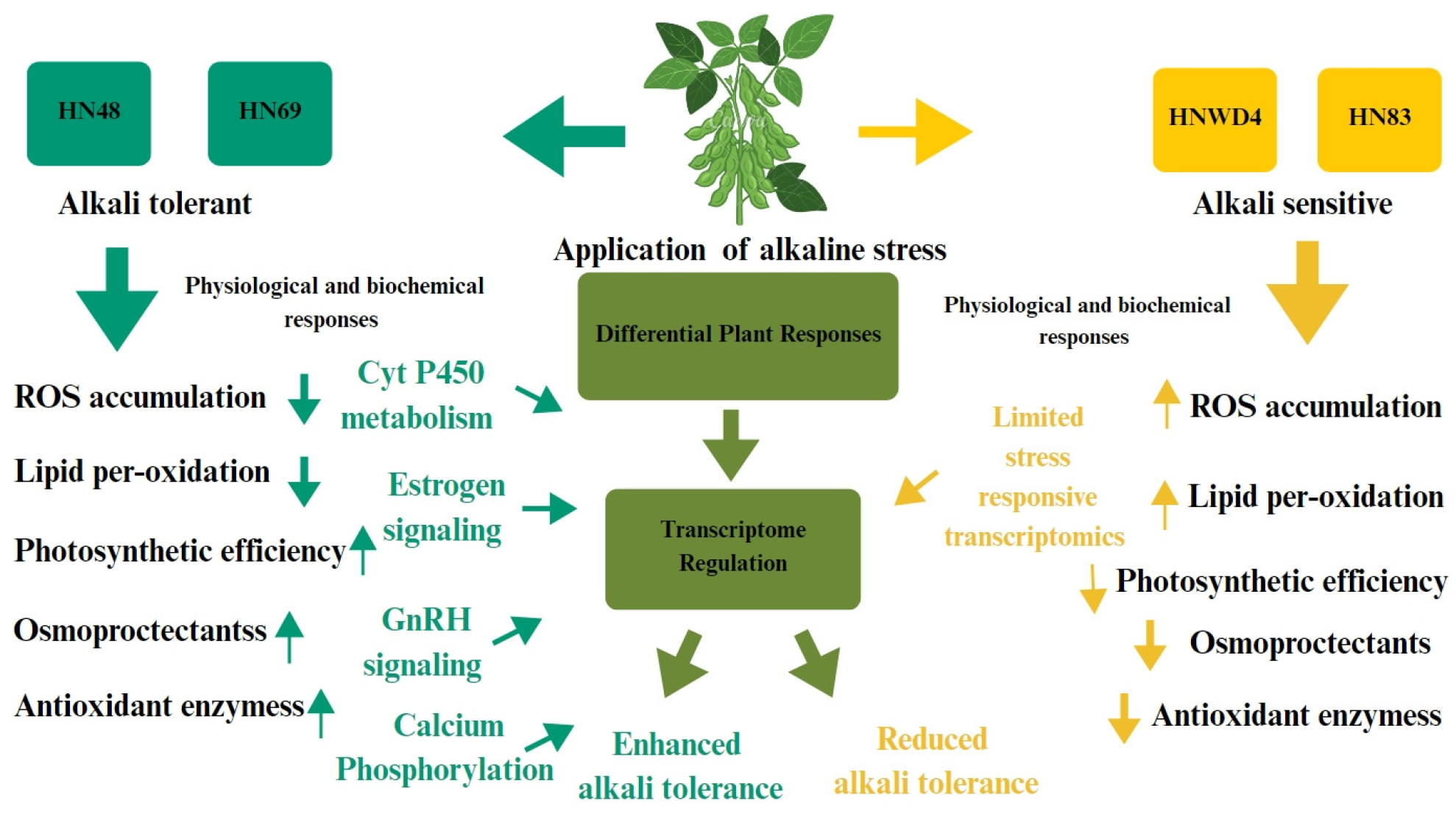

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Plant Materials

5.2. Morphological Assessment of Soybean Under Alkaline Stress

5.3. Physiological Assessment of Soybean Under Alkaline Stress

5.4. Measurement of MDA, H2O2, O2−, and Proline Contents

5.5. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

5.6. Stress Treatments, Cultivation of Soybean, and Total RNA Extraction

5.7. Analysis of RNA Sequencing Data

5.8. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

5.9. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HN48 | Heinong 48 |

| HN69 | Heinong 69 |

| HNWD4 | Heinong Wangdou 4 |

| HN83 | Heinong 83 |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

| O2− | Superoxide anion |

References

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, T.; Zhang, P.; Li, S.; Ye, S.; Yang, K.; Gai, Z.; Liu, L. Alkaline stress suppresses soybean waterlogging tolerance by exacerbating energy expenditure and ROS accumulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229, 110381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guo, L.; Wang, S.; Ren, M.; Zhao, P.; Huang, Z.; Jia, H.; Wang, J.; Lin, A. Comprehensive evaluation of the risk system for heavy metals in the rehabilitated saline-alkali land. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 347, 119117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Ahmed, M.Z.; Hussain, T.; Aziz, I.; Ahmad, N.; Gul, B.; Nielsen, B.L. Effects of Salinity Stress on Chloroplast Structure and Function. Cells 2021, 10, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Fang, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, K.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Fang, N.; Zhang, Y. Geochemical evaluation and driving factor analysis of soil salinization in Northeast China Plain. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1614178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Mu, C.; Du, D.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Xuan, W.; Kircher, S.; Palme, K.; Li, X.; Li, R. Alkaline stress reduces root waving by regulating PIN7 vacuolar transport. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1049144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Shen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, S.; Hu, J.; Feng, R.; Zhao, Q.; Du, J.; Du, Y. The Effect of Neutral Salt and Alkaline Stress with the Same Na+ Concentration on Root Growth of Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) Seedlings. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, H.H.; Liu, W.C.; Zhang, X.W.; Lu, Y.T. Ethylene Inhibits Root Elongation during Alkaline Stress through AUXIN1 and Associated Changes in Auxin Accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2015, 168, 1777–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Jin, S.; Yang, S. The Impact of Alkaline Stress on Plant Growth and Its Alkaline Resistance Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.; Liang, C.; Su, J.; Liang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Integrative transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis elucidates the vital pathways underlying the differences in salt stress responses between two chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) varieties. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; He, Q.; Ma, J.; Guo, H.; Shi, Q. Exogenous 2,4-Epibrassinolide Alleviates Alkaline Stress in Cucumber by Modulating Photosynthetic Performance. Plants 2024, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.J.; Wang, S.W.; Zhang, C.F.; Guo, T.; Hao, H.L.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wang, S.; Shu, J.M. Effects of leaf scorch on chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of walnut leaves. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 130, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, R.; Ge, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, R. Plants’ Response to Abiotic Stress: Mechanisms and Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Shi, F.; Li, H.; Ding, Y.; Chang, W.; Ping, Y.; Song, F. Piriformospora indica alleviates soda saline-alkaline stress in Glycine max by modulating plant metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1406542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Khan, M.A.; Tahir, M.H.N.; Lodhi, M.S.; Muzammil, S.; Shafiq, M.; Gechev, T.; Faisal, M. In Silico identification and characterization of SOS gene family in soybean: Potential of calcium in salinity stress mitigation. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Jia, B.; Sun, M.; Sun, X. Insights into the regulation of wild soybean tolerance to salt-alkaline stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1002302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fang, Y.; Xu, L.; Jin, X.; Iqbal, A.; Nisa, Z.U.; Ali, N.; Chen, C.; Shah, A.A.; Gatasheh, M.K. The Glycine soja cytochrome P450 gene GsCYP82C4 confers alkaline tolerance by promoting reactive oxygen species scavenging. Physiol. Plant 2024, 176, e14252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Niu, D.; Liu, X. Effects of abiotic stress on chlorophyll metabolism. Plant Sci. 2024, 342, 112030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Luo, X.; Croft, H.; Rogers, C.A.; Chen, J.M. Seasonal variation in the relationship between leaf chlorophyll content and photosynthetic capacity. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 3953–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnilickova, H.; Kraus, K.; Vachova, P.; Hnilicka, F. Salinity Stress Affects Photosynthesis, Malondialdehyde Formation, and Proline Content in Portulaca oleracea L. Plants 2021, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molassiotis, A.; Job, D.; Ziogas, V.; Tanou, G. Citrus Plants: A Model System for Unlocking the Secrets of NO and ROS-Inspired Priming Against Salinity and Drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Esawi, M.A.; Alaraidh, I.A.; Alsahli, A.A.; Alamri, S.A.; Ali, H.M.; Alayafi, A.A. Bacillus firmus (SW5) augments salt tolerance in soybean (Glycine max L.) by modulating root system architecture, antioxidant defense systems and stress-responsive genes expression. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 132, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inthaisong, S.; Boonchuen, P.; Tharapreuksapong, A.; Tittabutr, P.; Teaumroong, N.; Tantasawat, P.A. Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Mungbean Defense Mechanisms Against Powdery Mildew. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M. KEGG mapping tools for uncovering hidden features in biological data. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, X.U.; Xin-Yu, W.; Wang-Zhen, G. The cytochrome P450 superfamily: Key players in plant development and defense. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, S.; Cong, X.; Xu, F. Molecular and physiological response of chives (Allium schoenoprasum) under different concentrations of selenium application by transcriptomic, metabolomic, and physiological approaches. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 221, 109633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, A.; Du, H. Transcriptome analysis reveals the effects of hydrogen gas on NaCl stress in purslane roots. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 319, 112142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.S.; Mu, D.W.; Feng, N.J.; Zheng, D.F.; Sun, Z.Y.; Khan, A.; Zhou, H.; Song, Y.W.; Liu, J.X.; Luo, J.Q. Integrated Analyses Reveal the Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Brassinolide in Modulating Salt Tolerance in Rice. Plants 2025, 14, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Xin, Z.; Wei, L.; Tsegaw, M.; Xin, X.U.; Yan-Ping, Q.I.; Sapey, E.; Lu-Ping, L.; Ting-Ting, W.U.; Shi, S.; Tian-Fu, H. Principles and practices of the photo-thermal adaptability improvement in soybean. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper Enzymes in Isolated Chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Reprint of: Photoperoxidation in Isolated Chloroplasts I. Kinetics and Stoichiometry of Fatty Acid Peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 726, 109248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid Determination of Free Proline for Water-Stress Studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants. Protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. An. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstner, E.F.; Heupel, A. Formation of hydrogen peroxide by isolated cell walls from horseradish (Armoracia lapathifolia Gilib). Planta 1976, 130, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehly, A.C. The Assay of Catalases and Peroxidases; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tükenmez, H.; Magnussen, H.M.; Rogne, P.; Byström, A.; Wolf-Watz, M. Bridging in Vitro with in Vivo Enzymology. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 223a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Mai, K.K.K.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Kang, B.H.; Hwang, I.; et al. Chloroplast thylakoid ascorbate peroxidase PtotAPX plays a key role in chloroplast development by decreasing hydrogen peroxide in Populus tomentosa. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4333–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.A.; Hou, J.; Yao, N.; Xie, C.; Li, D. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Triplophysa yarkandensis in response to salinity and alkalinity stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part. D Genom. Proteom. 2020, 33, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qi, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. CARMO: A comprehensive annotation platform for functional exploration of rice multi-omics data. Plant J. 2015, 83, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xue, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Cao, D.; Tang, X.; Yao, Y.; He, W.; Chen, C.; Nisa, Z.; et al. Integrated Evaluation of Alkaline Tolerance in Soybean: Linking Germplasm Screening with Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Responses. Plants 2026, 15, 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020222

Xue Y, Wei Z, Zhang C, Wang Y, Cao D, Tang X, Yao Y, He W, Chen C, Nisa Z, et al. Integrated Evaluation of Alkaline Tolerance in Soybean: Linking Germplasm Screening with Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Responses. Plants. 2026; 15(2):222. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020222

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Yongguo, Zichun Wei, Chengbo Zhang, Yudan Wang, Dan Cao, Xiaofei Tang, Yubo Yao, Wenjin He, Chao Chen, Zaib_un Nisa, and et al. 2026. "Integrated Evaluation of Alkaline Tolerance in Soybean: Linking Germplasm Screening with Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Responses" Plants 15, no. 2: 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020222

APA StyleXue, Y., Wei, Z., Zhang, C., Wang, Y., Cao, D., Tang, X., Yao, Y., He, W., Chen, C., Nisa, Z., & Liu, X. (2026). Integrated Evaluation of Alkaline Tolerance in Soybean: Linking Germplasm Screening with Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Responses. Plants, 15(2), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020222