High Green Light Substitution Reduces Tipburn Incidence in Romaine Lettuce Grown in a Plant Factory with Artificial Lighting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

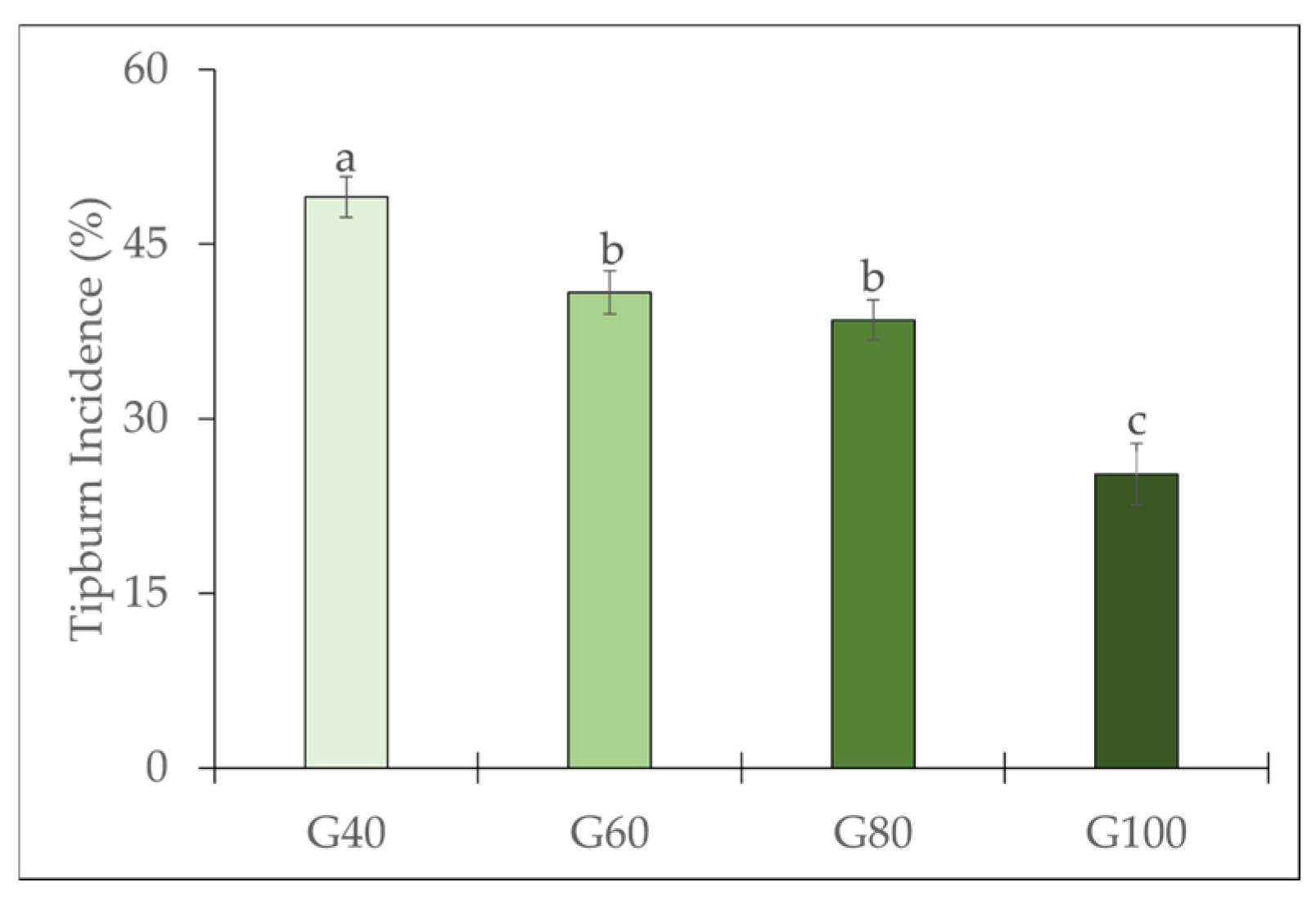

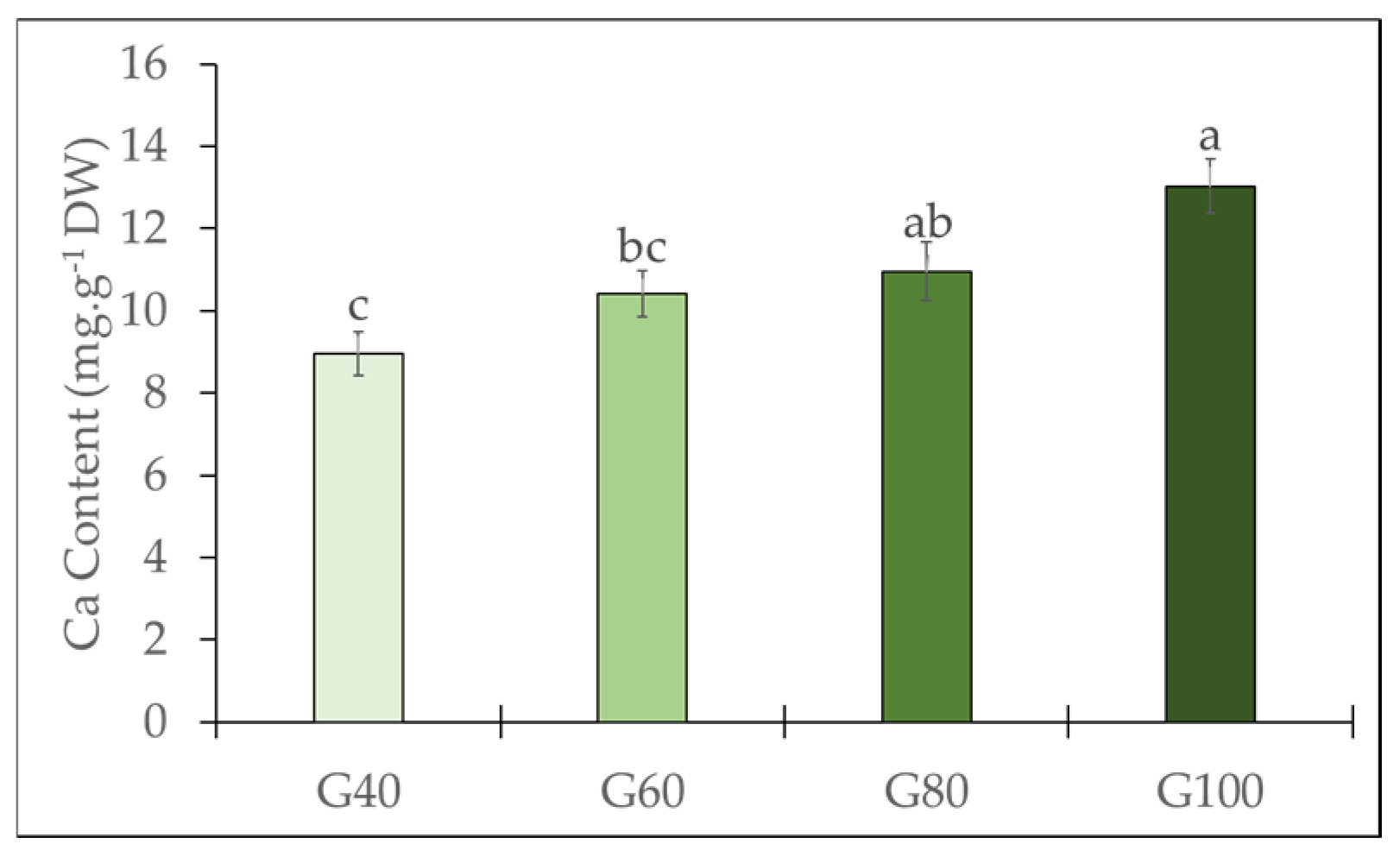

2.1. Tipburn Incidence and Calcium Content of the Inner Leaves

2.2. Plant Growth and Biomass

2.3. Gas Exchange Characteristics of Outer Leaves and Leaf Pigments

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of Green Light Substitution on Tipburn Incidence and Plant Growth

3.2. Effects of Green Light Substitution on Gas Exchange Characteristics and SPAD Values of Outer Leaves

3.3. Effects of Green Light Substitution on Calcium Content and Leaf Pigments in Inner Leaves

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Seedling Preparation

4.2. Growth Conditions and Experimental Setup

4.3. Measurements

4.3.1. Growth Parameters

4.3.2. Tipburn Evaluation and Calcium Content Analysis

4.3.3. Leaf Gas Exchange and Photosynthetic Pigments

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ertle, J.; Kubota, C. Reduced Daily Light Integral at the End of Production Can Delay Tipburn Incidence with a Yield Penalty in Indoor Lettuce Production. HortScience 2023, 58, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Nguyen, D.; Sakaguchi, S.; Akiyama, T.; Tsukagoshi, S.; Feldman, A.; Lu, N. Relation between relative growth rate and tipburn occurrence of romaine lettuce under different light regulations in a plant factory with LED lighting. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2020, 85, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertle, J.; Kubota, C. Testing Cultivar-specific Tipburn Sensitivity of Lettuce for Indoor Vertical Farms. HortScience 2023, 58, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thor, K. Calcium—Nutrient and Messenger. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, D. Calcium transport between tissues and its distribution in the plant. Plant Cell Environ. 2006, 7, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birlanga, V.; Acosta-Motos, J.R.; Pérez-Pérez, J.M. Mitigation of Calcium-Related Disorders in Soilless Production Systems. Agronomy 2022, 12, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, G.F.; Huntington, V.C. The relationship between leaf growth, calcium accumulation and distribution, and tipburn development in field-grown butterhead lettuce. Sci. Hortic. 1983, 21, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikiz, B.; Dasgan, H.; Öz, B. Mitigating Tipburn True Foliar Calcium Application in Indoor Hydroponicly Grown Mini Cos Lettuce. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 85, 01003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.A.; Yu-xin, T.; Qi-chang, Y. Lettuce plant growth and tipburn occurrence as affected by airflow using a multi-fan system in a plant factory with artificial light. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 88, 102496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhassel, P.; Bleyaert, P.; Van Lommel, J.; Vandevelde, I.; Crappé, S.; Van Hese, N.; Hanssens, J.; Steppe, K.; Van Labeke, M.-C. Rise of nightly air humidity as a measure for tipburn prevention in hydroponic cultivation of butterhead lettuce. In Proceedings of the XXIX International Horticultural Congress on Horticulture: Sustaining Lives, Livelihoods and Landscapes (IHC2014), Brisbane, Australia, 17–22 August 2014; International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS): Leuven, Belgium, 2015; pp. 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Kim, J. Light Quality Affects Water Use of Sweet Basil by Changing Its Stomatal Development. Agronomy 2021, 11, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cheng, W.; Yu, X.; Liang, K.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, F.; Chen, C.; Sun, B. Effect of Combined Light Quality and Calcium Chloride Treatments on Growth and Quality of Chinese Kale Sprouts. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johkan, M.; Shoji, K.; Goto, F.; Hahida, S.; Yoshihara, T. Effect of green light wavelength and intensity on photomorphogenesis and photosynthesis in Lactuca sativa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 75, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tong, Y.-X.; Lu, J.-L.; Li, Y.-M.; Liu, X.; Cheng, R.-F. Morphology, Photosynthetic Traits, and Nutritional Quality of Lettuce Plants as Affected by Green Light Substituting Proportion of Blue and Red Light. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 627311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, E.; Weerheim, K.; Schipper, R.; Dieleman, J.A. Partial replacement of red and blue by green light increases biomass and yield in tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 249, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sago, Y. Effects of Light Intensity and Growth Rate on Tipburn Development and Leaf Calcium Concentration in Butterhead Lettuce. HortScience 2016, 51, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; van Iersel, M.W. Photosynthetic Physiology of Blue, Green, and Red Light: Light Intensity Effects and Underlying Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 619987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.A.; Sheibani, F. Chapter 10—LED advancements for plant-factory artificial lighting. In Plant Factory, 2nd ed.; Kozai, T., Niu, G., Takagaki, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 167–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Grundy, S.; Hardy, K.; Yang, Q.; Lu, C. A Transcriptome Analysis Revealing the New Insight of Green Light on Tomato Plant Growth and Drought Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 649283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibbernsen, E.; Mott, K.A. Stomatal responses to flooding of the intercellular air spaces suggest a vapor-phase signal between the mesophyll and the guard cells. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.G.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, E.J.; Kim, E.A.; Nam, S.Y. Light Quality Influence on Growth Performance and Physiological Activity of Coleus Cultivars. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bian, Z.; Marcelis, L.F.M.; Heuvelink, E.; Yang, Q.; Kaiser, E. Green light is similarly effective in promoting plant biomass as red/blue light: A meta-analysis. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 5655–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Cao, Q.; Qiu, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z. Effect of Green Light Replacing Some Red and Blue Light on Cucumis melo under Drought Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hu, L.; Wu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Xiao, X.; Lyu, J.; Xie, J.; Yu, J. Green Light Partial Replacement of Red and Blue Light Improved Drought Tolerance by Regulating Water Use Efficiency in Cucumber Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 878932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y. Artificial photosynthesis systems for solar energy conversion and storage: Platforms and their realities. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 6704–6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saure, M.C. Causes of the tipburn disorder in leaves of vegetables. Sci. Hortic. 1998, 76, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Feng, J.; Wang, P.; Ding, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Su, H.; Tian, B.; et al. Transcriptome Analysis Revealed Hub Genes Related to Tipburn Resistance in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Plants 2025, 14, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Tian, S.; Di, Q.; Duan, S.; Dai, K. Effects of exogenous calcium on mesophyll cell ultrastructure, gas exchange, and photosystem II in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum Linn.) under drought stress. Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navazio, L.; Formentin, E.; Cendron, L.; Szabò, I. Chloroplast Calcium Signaling in the Spotlight. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asao, T.; Kitazawa, H.; Washizu, K.; Ban, T.; Pramanik, H. Effect of different nutrient levels on anthocyanin and nitrate-N contents in turnip grown in hydroponics. J. Appl. Hortic. 2005, 7, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamoto, H.; Yamazaki, K. The spectral ratio of red, green, and blue photon fluxes to the total flux of photosynthetic photons and the ratio of red to far-red photon fluxes of sunlight at Ayabe, Kyoto. Clim. Biosph. 2012, 12, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, Y.; Okubo, H.; Itoh, H.; Koyama, R. Reduction of leaf lettuce tipburn using an indicator cultivar. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 210, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertle, J.; Kubota, C. Nighttime Blue Lighting and Downward Airflow to Manage Tipburn in Indoor Farm Lettuce. HortScience 2025, 60, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The Spectral Determination of Chlorophylls a and b, as well as Total Carotenoids, Using Various Solvents with Spectrophotometers of Different Resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.P.; Lu, N.; Kagawa, N.; Kitayama, M.; Takagaki, M. Short-Term Root-Zone Temperature Treatment Enhanced the Accumulation of Secondary Metabolites of Hydroponic Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) Grown in a Plant Factory. Agronomy 2020, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density; PPFD (μmol m−2 s−1) | % Green Proportion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue (400–499 nm) | Green (500–599 nm) | Red (600–700 nm) | Total (400–700 nm) | ||

| G40 (Control) | 42 | 81 | 82 | 205 | 40 |

| G60 | 26 | 122 | 59 | 207 | 59 |

| G80 | 17 | 165 | 24 | 206 | 80 |

| G100 | 6 | 195 | 3 | 204 | 96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ruangsangaram, T.; Munyanont, M.; Nguyen, D.T.P.; Takagaki, M.; Lu, N. High Green Light Substitution Reduces Tipburn Incidence in Romaine Lettuce Grown in a Plant Factory with Artificial Lighting. Plants 2026, 15, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020208

Ruangsangaram T, Munyanont M, Nguyen DTP, Takagaki M, Lu N. High Green Light Substitution Reduces Tipburn Incidence in Romaine Lettuce Grown in a Plant Factory with Artificial Lighting. Plants. 2026; 15(2):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020208

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuangsangaram, Thanit, Maitree Munyanont, Duyen T. P. Nguyen, Michiko Takagaki, and Na Lu. 2026. "High Green Light Substitution Reduces Tipburn Incidence in Romaine Lettuce Grown in a Plant Factory with Artificial Lighting" Plants 15, no. 2: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020208

APA StyleRuangsangaram, T., Munyanont, M., Nguyen, D. T. P., Takagaki, M., & Lu, N. (2026). High Green Light Substitution Reduces Tipburn Incidence in Romaine Lettuce Grown in a Plant Factory with Artificial Lighting. Plants, 15(2), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020208