Exploring the Functional Roles of Endophytic Bacteria in Plant Stress Tolerance for Sustainable Agriculture: Diversity, Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Endophytic Bacterial Diversity

2.1. Proteobacteria

- Alpha-proteobacteria: Rhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, and Agrobacterium are among the genera that belong to this class. Given their capacity to fix nitrogen and promote the growth of plants, Rhizobium species are essential for sustainable agriculture because of their symbiotic relationship with host plants, which not only promotes plant development by promoting the development of root nodules where they transform ambient nitrogen into ammonia—a type of nitrogen source that plants may easily use but also increases soil fertility [11].

- Beta-proteobacteria: This class comprises Herbaspirillum and Burkholderia, which are well known for plant growth-promoting and biocontrol properties. Burkholderia spp. colonizes plant roots and internal tissues, enhances nutrient acquisition, and produces lipopeptides and bioactive compounds that suppress pathogens, thereby reducing biotic stress. Herbaspirillum species are also known to fix nitrogen and stimulates phytohormone production to improve plant growth and stress tolerance [12].

- Gamma-proteobacteria: Pseudomonas and Enterobacter are two genera that belong to the class Gamma-proteobacteria. The ability of these bacteria to biocontrol plant diseases is well known. Many antimicrobial substances, such as hydrogen cyanide, phenazines, and pyoverdines, are produced by Pseudomonas species that can inhibit the growth of pathogenic microbes [13,14].

2.2. Actinobacteria

- Streptomyces: Streptomyces species generate a wide spectrum of antibacterial and antifungal compounds that suppress soil-borne pathogens and diseases and impart biotic stress tolerance. They play key role in decomposition and nitrogen cycling, improving soil organic matter quality and nutrient supply, which strengthens plant tolerance under various abiotic stresses [16].

- Micromonospora: Bioactive compounds produced by Micromonospora species protect plants against infections and promote plant growth. By breaking down complex organic molecules, they release nutrients that can be readily absorbed by plants. Additionally, these bacteria produce siderophores, which chelate iron and increase its availability to plants, enhancing their uptake of nutrients [17].

2.3. Firmicutes

- Bacillus: The genus Bacillus comprises some of the most well-characterized endophytic bacteria, owing to their remarkable ability to form endospores. This attribute allows them to withstand extreme conditions, including drought, salinity, heat, and nutrient limitation. Bacillus spp. plays a crucial role in enhancing plant stress tolerance by producing phytohormones, osmoprotectants, and exopolysaccharides, which collectively promote root development and improve plant water retention in challenging environments [19].

- Paenibacillus: Paenibacillus spp. plays critical role in nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, and extracellular enzyme production, which together alleviate the impacts of various abiotic stresses. Induced phytohormones and volatile organic compounds stimulate root system development and enhance tolerance to drought and salinity, while their consistent detection across plant tissues indicates a central role in structuring stress-adaptive endophytic consortia [20].

- Staphylococcus: Endophytic Staphylococcus spp. tolerates osmotic stress, desiccation and high salinity, and produce enzymes and metabolites that support nutrient cycling in stressed soils. Their documented antagonism against phytopathogens suggests an auxiliary role in plant defense, particularly under combined abiotic–biotic stress scenarios [21].

2.4. Bacteroidetes

- Chryseobacterium: These endophytes secrete degradative enzymes that mineralize complex organic matter, improving nutrient availability in depleted soils. Many strains also synthesize antifungal compounds that protect plants from pathogenic fungi there by reducing disease-related stress [23].

- Flavobacterium species helps nutrient cycling through extracellular enzyme production and can promote root growth and water and nutrient uptake. Their activity improves soil structure and fertility, indirectly increasing plant tolerance to drought and nutrient stress [24].

2.5. Other Phyla

- Acidobacteria: Adapted to acidic environments, Acidobacteria contribute to decomposition of complex organic matter and nutrient release in acid soils, thereby improving plant nutrition under pH-stress conditions. Although their plant interactions are less understood, they are increasingly recognized as important for maintaining soil health and buffering plants against nutrient stress in acidic ecosystems [25].

- Planctomycetes: Planctomycetes possess unusual cell biology and versatile metabolism, enabling participation in nitrogen and carbon cycling within plant-associated habitats. Through biofilm formation and specialized pathways (e.g., lipid-related metabolism), they support root-associated nutrient transformations and contribute to long-term soil carbon turnover, indirectly enhancing plant tolerance to nutrient and environmental stresses [26].

2.6. Methods of Endophytic Bacteria Identification

- Culture-Based Techniques: For the purpose of isolating and characterizing endophytic bacteria, culture-based techniques are indispensable. In order to prevent the contamination of endophytic bacteria and isolation of pure cultures require proper surface sterilization of plant tissues and then inoculation into specific culture media. Biochemical and physiological analysis can be used to define isolated strains, offering information on their metabolic capabilities and adaptabilities. Although culture-based methods provide insightful information, their limits in growing fastidious or uncultivable species may lead to an underestimation of bacterial diversity [27].

- Molecular and Genomic Techniques: High-throughput investigations of microbial communities have been made possible by advances in molecular biology and genomic techniques, which have significantly advanced the study of endophytic bacteria. The PCR-based methods such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing and ITS sequencing can be used to accurately identify and classify endophytic bacteria. While Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) provides the identification and localization of specific bacterial taxa within plant tissues and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and genomic technologies offer comprehensive insights into microbial diversity and community structure [28].

- Functional Analysis: Functional analytic techniques, such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics approaches offer deeper insights into the dynamics and function of gene expression/function and metabolic activities of endophytic bacteria. For instance, proteome investigations clarify the functional protein activities and composition, and metabolic techniques reveal the metabolic ranges and potential function of endophytic bacteria. Plant–microbe interactions are governed by regulatory networks and patterns of gene expression that are revealed by transcriptomic research. These functional assessments give crucial information about the functional roles of endophytic bacteria in plant growth, ecosystem functioning, and stress responses [29].

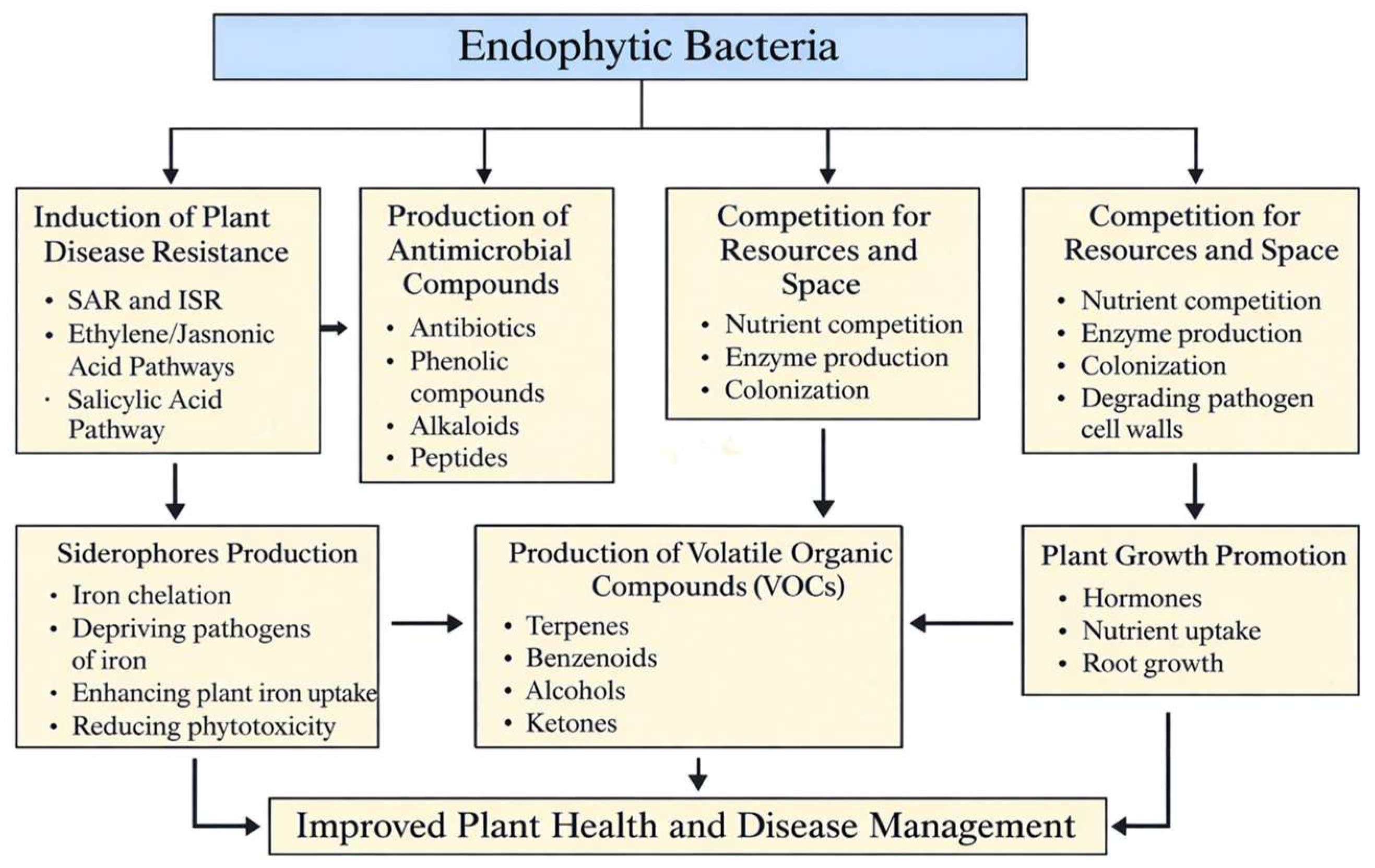

3. Endophytic Bacteria Can Inhibit Pathogens Directly Through Different Mechanisms

3.1. Activation of Plant Systemic Disease Resistance

3.2. Production of Antimicrobial Compounds

3.3. Competition for Resources and Space

3.4. Siderophores Production

3.5. Production of Volatile Organic Compounds

4. Endophytic Bacteria Induced Abiotic Stress Tolerance

4.1. Role in Salt Tolerance

4.2. Role in Drought Tolerance

5. Endophytic Bacteria and Soil Health

6. Applications of Endophytic Bacteria in Agriculture

7. Environmental Issues, Challenges, and Limitations

8. Conclusions and Future Prospectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumari, P.; Deepa, N.; Trivedi, P.K.; Singh, B.K.; Srivastava, V.; Singh, A. Plants and endophytes interaction: A “secret wedlock” for sustainable biosynthesis of pharmaceutically important secondary metabolites. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 226. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani, N.; Maheshwari, R.; Kumar, P.; Dahiya, R.; Suneja, P. Bioprospecting for extracellular enzymes from endophytic bacteria isolated from Vigna radiata and Cajanus cajan. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mengistu, A.A. Endophytes: Colonization, behaviour, and their role in defense mechanism. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 6927219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madbouly, A.K. Endophytic fungi as sources of novel natural compounds. In Plant Mycobiome: Diversity, Interactions and Uses; Rashad, Y.M., Baka, Z.A.M., Moussa, T.A.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 339–373. [Google Scholar]

- Lovecká, P.; Kroneislová, G.; Novotná, Z.; Röderová, J.; Demnerová, K. Plant growth-promoting endophytic bacteria isolated from Miscanthus giganteus and their antifungal activity. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.K.; Huang, W.D.; Wang, P.H.; Lin, W.L.; Chen, H.Y.; Rau, S.T.; Lee, M.H. The rice endophytic bacterium Bacillus velezensis LS123N provides protection against multiple pathogens and enhances rice resistance to wind with increase in yield. Biol. Control 2024, 192, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Agri, U.; Chaudhary, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, G. Endophytes and their potential in biotic stress management and crop production. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 933017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, M.; Mahmood, A.; Sahkoor, A.; Zia, M.A.; Ullah, M.S. The role of endophytes to combat abiotic stress in plants. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, I.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Sikandar, S.; Shahzad, S. Plant beneficial endophytic bacteria: Mechanisms, diversity, host range and genetic determinants. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 221, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikhudo, P.P.; Ntushelo, K.; Mudau, F.N. Sustainable applications of endophytic bacteria and their physiological/biochemical roles on medicinal and herbal plants: Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, T.J.G.; Andersson, S.G.E. The α-Proteobacteria: The Darwin finches of the bacterial world. Biol. Lett. 2009, 5, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachate, S.P.; Khapare, R.M.; Kodam, K.M. Oxidation of arsenite by Two β-proteobacteria isolated from soil. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaterra, A.; Badosa, E.; Daranas, N.; Francés, J.; Roselló, G.; Montesinos, E. Bacteria as biological control agents of plant diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balthazar, C.; Joly, D.L.; Filion, M. Exploiting beneficial Pseudomonas spp. for cannabis production. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 833172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, M.S.M.; Abdelhamid, S.A.; Mohamed, S.S. Secondary metabolites and biodiversity of Actinomycetes. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi-Zarandi, M.; Saberi Riseh, R.; Tarkka, M.T. Actinobacteria as effective biocontrol agents against plant pathogens, an overview on their role in eliciting plant defense. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zeng, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H. Micromonospora: A prolific source of bioactive secondary metabolites with therapeutic potential. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8735–8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźniar, A.; Kruczyńska, A.; Włodarczyk, K.; Vangronsveld, J.; Wolińska, A. Endophytes as permanent or temporal inhabitants of different ecological niches in sustainable agriculture. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Lee, D.; Lee, S.; Kong, H.J.; Park, J.; Seo, Y.-S. Comparative genomic analysis of Chryseobacterium species: Deep insights into plant-growth-promoting and halotolerant capacities. Microb. Genom. 2023, 9, 001108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, H.; Subramanian, S.; Geitmann, A.; Smith, D.L. Bacillus and Paenibacillus as plant growth-promoting bacteria in soybean and cannabis. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1529859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, A.; Krishna, A.; Nair, I.C.; Radhakrishnan, E.K. Drought tolerant and plant growth promoting endophytic Staphylococcus sp. having synergistic effect with silicate supplementation. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 1899–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kim, Y.J.; Farh, M.E.A.; Dan, W.D.; Kang, C.H.; Yang, D.C. Chryseobacterium panacis sp. nov., isolated from Ginseng Soil. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2016, 109, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.W. The plant-associated Flavobacterium: A hidden helper for improving plant health. Plant Pathol. J. 2024, 40, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, S.; Basu, A.; Ahmad, I.; Sayyed, R.Z.; El-Enshasy, H.A.; Dailin, D.J.; Suriani, N.L. Recent understanding of soil Acidobacteria and their ecological significance: A critical review. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 580024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboré, O.D.; Godreuil, S.; Drancourt, M. Planctomycetes as host-associated bacteria: A perspective that holds promise for their future isolations, by mimicking their native environmental niches in clinical microbiology laboratories. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 519301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, E.N.; Novero, A. Identification and characterisation of endophytic bacteria from coconut (Cocos nucifera) tissue culture. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2020, 31, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Kumar, P.; Dahiya, P.; Maheshwari, R.; Dang, A.S.; Suneja, P. Endophytism: A multidimensional approach to plant–prokaryotic microbe interaction. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 861235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yang, B.; Gao, A.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, F.J. Transformation of Arsenic species by diverse endophytic bacteria of rice roots. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Cabrera, B.E.; Delgado-Alvarado, A.; Salgado-Garciglia, R.; López-Valdez, L.G.; Sánchez-Herrera, L.M.; Montiel-Montoya, J.; Cureño, H.J.B. volatile organic compound produced by bacteria: Characterization and application. In Bacterial Secondary Metabolites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, C.; Mo, X.; Tan, Q.; He, Y.; Zhou, G. The multifunctions and future prospects of endophytes and their metabolites in plant disease management. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusajima, M.; Shima, S.; Fujita, M.; Minamisawa, K.; Che, F.S.; Yamakawa, H.; Nakashita, H. Involvement of ethylene signaling in Azospirillum sp. B510-induced disease resistance in rice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 1522–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.M.; Ismael, W.H.; Mahfouz, A.Y.; Daigham, G.E.; Attia, M.S. Efficacy of endophytic bacteria as promising inducers for enhancing the immune responses in tomato plants and managing Rhizoctonia root-rot disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, N.; Hartmann, M.; Abts, S.; Abts, L.; Reinartz, E.; Altavilla, A.; Zeier, J. In depth analysis of isochorismate synthase derived metabolism in plant immunity: Identification of meta substituted benzoates and salicyloyl malate. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 104847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcion, C.; Lohmann, A.; Lamodière, E.; Catinot, J.; Buchala, A.; Doermann, P.; Métraux, J.P. Characterization and biological function of the ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE2 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoel, S.H.; Dong, X. Salicylic acid in plant immunity and beyond. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghari, S.; Harighi, B.; Ashengroph, M.; Clement, C.; Aziz, A.; Esmaeel, Q.; Ait Barka, E. Induction of systemic resistance to Agrobacterium tumefaciens by endophytic bacteria in grapevine. Plant Pathol. 2020, 69, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Gong, M.; Guan, Q. Induced disease resistance of endophytic bacteria reb01 to bacterial blight of rice. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2079, p. 020017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumyantsev, S.D.; Alekseev, V.Y.; Sorokan, A.V.; Burkhanova, G.F.; Cherepanova, E.A.; Garafutdinov, R.R.; Maksimov, I.V.; Veselova, S.V. Additive effect of the composition of endophytic bacteria Bacillus subtilis on systemic resistance of wheat against greenbug aphid Schizaphis graminum Due to Lipopeptides. Life 2023, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Van der Does, D.; Zamioudis, C.; Leon-Reyes, A.; Van Wees, S.C.M. Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012, 28, 489–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, H.; You, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Aimaier, R.; Zhang, J.; Han, S.; Zhao, H.; et al. Transcriptome and metabolome analyses reveal that Bacillus subtilis BS-Z15 lipopeptide mycosubtilin homolog mediates plant defense responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1088220. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Wei, L.; Ma, J.; Wan, Y.; Huang, K.; Sun, Y.; Wen, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Yu, D.; et al. Bacillus cereus NJ01 induces salicylic acid- and abscisic acid-mediated immunity against bacterial pathogens through the EDS1–WRKY18 module. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 115017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, B.; Cheng, P.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, L.; Xing, J.; Dong, Z.; Yu, G. Endophytic Bacillus subtilis TR21 enhances banana resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense and promotes root growth via jasmonate and brassinosteroid biosynthesis pathways. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Yan, S. RNA-Seq identification of candidate defense genes targeted by endophytic Bacillus cereus-mediated induced systemic resistance against Meloidogyne incognita in tomato. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 2793–2805. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, H.; Sun, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, A.; Han, D.; Wei, G.; Shu, D. Host genotype specific rhizosphere fungus enhances drought resistance in wheat. Microbiome 2024, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.; Zeng, J.; Ning, Q.; Liu, H.; Bu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y. Ferroptosis induction in host rice by endophyte OsiSh 2 is necessary for mutualism and disease resistance in symbiosis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beiranvand, M.; Amin, M.; Hashemi-Shahraki, A.; Romani, B.; Yaghoubi, S.; Sadeghi, P. Antimicrobial Activity of endophytic bacterial populations isolated from medical plants of Iran. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2017, 9, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mamarasulov, B.; Davranov, K.; Umruzaqov, A.; Ercisli, S.; Alharbi, S.A.; Ansari, M.J.; Krivosudská, E.; Datta, R.; Jabborova, D. Evaluation of the antimicrobial and antifungal activity of endophytic bacterial crude extracts from medicinal plant Ajuga turkestanica (Rgl.) Brig (Lamiaceae). J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2023, 35, 102644. [Google Scholar]

- Priyanto, J.A.; Prastya, M.E.; Hening, E.N.W.; Suryanti, E.; Kristiana, R. Two strains of endophytic Bacillus velezensis carrying antibiotic-biosynthetic genes show antibacterial and antibiofilm activities against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Indian J. Microbiol. 2024, 64, 1884–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek-Ramos, M.J.; Gomez-Flores, R.; Orozco-Flores, A.A.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C.; González-Ochoa, G.; Tamez-Guerra, P. Bioactive products from plant-endophytic gram-positive bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Mallubhotla, S. Diversity, Antimicrobial activity, and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of endophytic bacteria sourced from Cordia dichotoma L. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 879386. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.N.; Ali, M.S.; Choi, S.J.; Hyun, J.W.; Baek, K.H. Biocontrol of citrus canker disease caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri using an endophytic Bacillus thuringiensis. Plant Pathol. J. 2019, 35, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, N.; Singh, S.K.; Yadav, N.; Singh, V.K.; Kumari, M.; Kumar, D.; Shukla, L.; Kaushalendra; Bhardwaj, N.; Kumar, A. Biocontrol screening of endophytes: Applications and limitations. Plants 2023, 12, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, A.; Eid, N.A.; Hassan, A.R.; Mahmoudi, H. Differential responses in some quinoa genotypes of a consortium of beneficial endophytic bacteria against bacterial leaf spot disease. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1167250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutungi, P.M.; Wekesa, V.W.; Onguso, J.; Kanga, E.; Baleba, S.B.; Boga, H.I. Culturable bacterial endophytes associated with shrubs growing along the draw-down zone of lake Bogoria, Kenya: Assessment of antifungal potential against Fusarium solani and induction of bean root rot protection. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 796847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, B.S.; Babalola, O.O.; Glick, B.R. Plant growth-promoting root-colonizing bacterial endophytes. Rhizosphere 2021, 20, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, S.; Shafiq, M.; Tariq, M.R.; Sami, A.; Nawaz-Ul-Rehman, M.S.; Bhatti, M.H.T.; Haider, M.S.; Sadiq, S.; Abbas, M.T.; Hussain, M.; et al. Interaction between bacterial endophytes and host plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1092105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadarshini, C.; Lal, R.; Yuan, P.; Liu, W.; Adhikari, A.; Bhandari, S.; Xia, Y. Plant disease suppressiveness enhancement via soil health management. Biology 2025, 14, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraepiel, A.M.L.; Bellenger, J.-P.; Wichard, T. Multiple roles of siderophores in free-living nitrogen-fixing bacteria. BioMetals 2009, 22, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grobelak, A.; Hiller, J. Bacterial siderophores promote plant growth: Screening of catechol and hydroxamate siderophores. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2017, 19, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Dubey, A.K. Diversity and applications of endophytic Actinobacteria of plants in special and other ecological niches. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.; Svatos, A.; Merten, D.; Büchel, G.; Kothe, E. Hydroxamate siderophores produced by Streptomyces acidiscabies e13 bind nickel and promote growth in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) Under Nickel Stress. Can. J. Microbiol. 2008, 54, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotb, E.; Al-Abdalall, A.H.; Ababutain, I.; AlAhmady, N.F.; Aldossary, S.; Alkhaldi, E.; Alghamdi, A.I.; Alzahrani, H.A.S.; Almuhawish, M.A.; Alshammary, M.N.; et al. Anticandidal activity of a siderophore from marine endophyte Pseudomonas aeruginosa Mgrv7. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, M.; Zheng, H. Whole-genome analysis revealed the growth-promoting and biological control mechanism of the endophytic bacterial strain Bacillus halotolerans Q2H2, with strong antagonistic activity in potato plants. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1287921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Rana, A.; Dhaka, R.K.; Singh, A.P.; Chahar, M.; Singh, S.; Nain, L.; Singh, K.P.; Minz, D. Bacterial volatile organic compounds as biopesticides, growth promoters and plant-defense elicitors: Current understanding and future scope. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 63, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, O.A.C.; De Araujo, N.O.; Mulato, A.T.N.; Persinoti, G.F.; Sforça, M.L.; Calderan-Rodrigues, M.J.; Oliveira, J.V.D.C. Bacterial volatile organic compounds (vocs) promote growth and induce metabolic changes in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1056082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; Wu, M.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Niu, N.; Li, S.; Chen, L. Volatile organic compounds (vocs) from plants: From release to detection. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 158, 116872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, R.; Khushhal, S.; Asif, T.; Mubeen, S.; Saranraj, P.; Sayyed, R.Z. Inhibition of bacterial and fungal phytopathogens through volatile organic compounds produced by Pseudomonas sp. In Secondary Metabolites and Volatiles of PGPR in Plant-Growth Promotion; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefvand, M.; Harighi, B.; Azizi, A. Volatile compounds produced by endophytic bacteria adversely affect the virulence traits of Ralstonia solanacearum. Biol. Control 2023, 178, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazala, I.; Chiab, N.; Saidi, M.N.; Gargouri-Bouzid, R. Volatile organic compounds from bacillus mojavensis i4 promote plant growth and inhibit phytopathogens. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 121, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Shameem, N.; Jatav, H.S.; Sathyanarayana, E.; Parray, J.A.; Poczai, P.; Sayyed, R.Z. Fungal endophytes to combat biotic and abiotic stresses for climate-smart and sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 953836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.T.; Tariq, M.; Abdullah, M.; Ullah, M.K.; Rafiq, A.R.; Siddique, A.; Shahid, M.S.; Ahmed, T.; Jamil, I. Salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting bacteria (ST-PGPB): An effective strategy for sustainable food production. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, C.; Asudi, G.O.; Okoth, P.; Reichelt, M.; Muoma, J.O.; Furch, A.C.; Oelmüller, R. Rhizobia contribute to salinity tolerance in common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Cells 2022, 11, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasseen, B.T.; Al-Thani, R.F. Endophytes and halophytes to remediate industrial wastewater and saline soils: Perspectives from Qatar. Plants 2022, 11, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinzer, M.; Ahmad, N.; Nielsen, B.L. Halophilic plant-associated bacteria with plant-growth-promoting potential. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Godínez, L.J.; Aguirre-Noyola, J.L.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Arteaga-Garibay, R.I.; Ireta-Moreno, J.; Ruvalcaba-Gómez, J.M. A look at plant-growth-promoting bacteria. Plants 2023, 12, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; He, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Lv, X.; Pu, X.; Zhuang, L. Community distribution of rhizosphere and endophytic bacteria of ephemeral plants in desert-oasis ecotone and analysis of environmental driving factors. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 1182–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, E.; Mishra, J.; Arora, N.K. Multifaceted interactions between endophytes and plant: Developments and prospects. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Verma, A.; Pal, G.; Anubha; White, J.F.; Verma, S.K. Seed endophytic bacteria of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) promote seedling development and defend against a fungal phytopathogen. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 774293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.F.; Chang, X.; Kingsley, K.L.; Zhang, Q.; Chiaranunt, P.; Micci, A.; Velazquez, F.; Elmore, M.; Crane, S.; Li, S.; et al. Endophytic bacteria in grass crop growth promotion and biostimulation. Grass Res. 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, S.; Bauddh, K.; Singh, R.P. Native Rhizospheric microbes mediated management of biotic stress and growth promotion of tomato. Sustainability 2022, 15, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, N.; Mansotra, R.; Ambardar, S.; Vakhlu, J.; Kole, C.; Salami, S.A.; Ambardar, A. Cultromic and metabarcodic insights into saffron-microbiome associations. In The Saffron Genome, 1st ed.; Vakhlu, J., Ambardar, S., Salami, S.A., Kole, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, Q.; Xiukang, W.; Haider, F.U.; Kučerik, J.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Holatko, J.; Naseem, M.; Kintl, A.; Ejaz, M.; Naveed, M.; et al. Rhizosphere bacteria in plant growth promotion, biocontrol, and bioremediation of contaminated sites: A comprehensive review of effects and mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, M.; Javed, M.R.; Tariq, A.; Usama, M.; Hanif, H.I.; Sadia, B.; Naheed, S. Endophyte bacterial metabolites: An active syrup for improvement of growth, biomass, and antioxidant system of Zea mays L. in drought condition. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 7186–7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egamberdieva, D.; Wirth, S.J.; Shurigin, V.V.; Hashem, A.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Endophytic bacteria improve plant growth, symbiotic performance of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and induce suppression of root rot caused by Fusarium solani under salt stress. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, M.; Swennen, R.; Mahuku, G. Unlocking the Microbiome Communities of Banana (Musa spp.) Under Disease Stressed (Fusarium wilt) and Non-Stressed Conditions. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.; Palombo, E.A.; Castillo, A.J.; Zaferanloo, B. Endophytes in Agriculture: Potential to Improve Yields and Tolerances of Agricultural Crops. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, P.; Mahawar, H.; Agarrwal, R.; Kajal; Gautam, V.; Deshmukh, R. Advancement in the molecular perspective of plant-endophytic interaction to mitigate drought stress in plants. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 981355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etesami, H.; Mirsyed, H.; Alikhani, H.A. In planta selection of plant growth promoting endophytic bacteria for rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014, 14, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Xiong, Z.; Chu, L.; Li, W.; Soares, M.A.; White, J.F., Jr.; Li, H. Bacterial communities of three plant species from Pb-Zn contaminated sites and plant-growth promotional benefits of endophytic Microbacterium sp. (strain BXGe71). J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 370, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Yang, D.; Wang, W.; Ji, J.; Jin, C.; Guan, C. Endophytic bacteria associated with the enhanced cadmium resistance in NHX1-overexpressing tobacco plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 188, 104524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Gong, Y.; Liu, S.; Ji, M.; Tang, R.; Kong, D.; Xue, Z.; Wang, L.; Hu, F.; Huang, L.; et al. Endophytic bacterial communities in wild rice (Oryza officinalis) and their plant growth-promoting effects on perennial rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1184489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Asaf, S.; Khan, A.L.; Adhikari, A.; Jan, R.; Ali, S.; Imran, M.; Kim, K.M.; Lee, I.J. Plant growth-promoting endophytic bacteria augment growth and salinity tolerance in rice plants. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 850–862. [Google Scholar]

- Juby, S.; Soumya, P.; Jayachandran, K.; Radhakrishnan, E.K. Morphological, metabolomic and genomic evidences on drought stress protective functioning of the endophyte Bacillus safensis Ni7. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsavkelova, E.A.; Volynchikova, E.A.; Potekhina, N.V.; Lavrov, K.V.; Avtukh, A.N. Auxin production and plant growth promotion by Microbacterium albopurpureum sp. nov. from the rhizoplane of leafless Chiloschista parishii Seidenf. orchid. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1360828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslennikova, D.; Koryakov, I.; Yuldashev, R.; Avtushenko, I.; Yakupova, A.; Lastochkina, O. Endophytic plant growth-promoting bacterium Bacillus subtilis reduces the toxic effect of cadmium on wheat plants. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xi, N.; Lang, D.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Potential biocontrol and plant growth promotion of an endophytic bacteria isolated from Glycyrrhiza uralensis seeds. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2022, 32, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.; Hou, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, T.; Dai, X.; Igarashi, Y.; Fan, L.; Yang, C.; Luo, F. Plant growth-promoting and arsenic accumulation reduction effects of two endophytic bacteria isolated from Brassica napus. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wu, H.; Pu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Hu, X.; Li, O. Complete genome of Sphingomonas paucimobilis ZJSH1, an endophytic bacterium from Dendrobium officinale with stress resistance and growth promotion potential. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Yang, C.; Wei, L.; Cui, L.; Osei, R.; Cai, F.; Ma, T.; Wang, Y. Transcriptome analysis of Stipa purpurea interacted with endophytic Bacillus subtilis in response to temperature and ultraviolet stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 98, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Yang, C.; Tao, W.; Li, S. Polysaccharides produced by plant growth-promoting Rhizobacteria strain Burkholderia sp. BK01 enhance salt stress tolerance to Arabidopsis thaliana. Polymers 2024, 16, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenzato, G.; Fani, R. Endophytic bacteria: A sustainable strategy for enhancing medicinal plant cultivation and preserving microbial diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1477465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, J.; Deepika, D.S.; Sridevi, M. Screening and isolation of plant growth promoting, halotolerant endophytic bacteria from mangrove plant Avicennia officinalis L. at Coastal Region of Corangi Andhra Pradesh. Agric. Sci. Dig. 2023, 43, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadaoui, M.; Faize, M.; Rifai, A.; Tayeb, K.; Youssef, N.O.B.; Kharrat, M.; Roeckel-Drevet, P.; Chaar, H.; Venisse, J.S. Evaluation of Tunisian wheat endophytes as plant growth promoting bacteria and biological control agents against Fusarium culmorum. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbe, A.A.; Gupta, S.; Stirk, W.A.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Growth-promoting characteristics of fungal and bacterial endophytes isolated from a drought-tolerant mint species Endostemon obtusifolius (E. Mey. ex Benth.) N. E. Br. Plants 2023, 12, 638. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, A.; Aslam, U.; Ferdous, S.; Qin, M.; Siddique, A.; Billah, M.; Naeem, M.; Mahmood, Z.; Kayani, S. Combined effect of endophytic Bacillus mycoides and rock phosphate on the amelioration of heavy metal stress in wheat plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.I.; Gomaa, E.Z. Effect of plant growth promoting Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens on growth and pigment composition of radish plants (Raphanus sativus) under NaCl stress. Photosynthetica 2012, 50, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Luo, S.; Chen, L.; Xiao, X.; Xi, Q.; Wei, W.; Zeng, G.; Liu, C.; Wan, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Bioremediation of heavy metals by growing hyperaccumulator endophytic bacterium Bacillus sp. L14. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8599–8605. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, W.; He, X.; Chen, J.; Geng, X.; Xiao, M. Induction of toluene degradation and growth promotion in corn and wheat by horizontal gene transfer within endophytic bacteria. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.T.; Saeed, A.; Mustafa, T.; Afzal, M. Augmentation with potential endophytes enhances phytostabilization of Cr in contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 7021–7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Dong, Y.; Li, B.; He, Y. Effects of endophyte inoculation on rhizosphere and endosphere microecology of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) grown in vanadium contaminated soil and its enhancement on phytoremediation. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, J.C.; Ladha, J.K.; Dazzo, F.B.; Yanni, Y.G.; Rolfe, B.G. Rhizobial inoculation influences seedling vigor and yield of rice. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.L.M.; Urquiaga, S.; Döbereiner, J.; Baldani, J.I. The effect of inoculating endophytic N2-fixing bacteria on micropropagated sugarcane plants. Plant Soil 2002, 242, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.H.; Schmidt, D.D.; Baldwin, I.T. Native bacterial endophytes promote host growth in a species-specific manner: Phytohormone manipulations do not result in common growth responses. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamizhvendan, R.; Yu, Y.J.; Lee, S.H.; Rhee, Y.H. Diversity of endophytic bacteria in ginseng and their potential for plant growth promotion. J. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, S.L.; Joubert, P.M.; Doty, S.L. Bacterial Endophyte Colonization and Distribution within Plants. Microorganisms 2017, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byregowda, R.; Prasad, S.R.; Oelmüller, R.; Nataraja, K.N.; Kumar, M.K.P. Is endophytic Colonization of Host Plants a Method of Alleviating Drought Stress? Conceptualizing the Hidden World of Endophytes. Int. J. M. Sci. 2022, 23, 9194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.C.; Guzmán, J.P.S.; Shay, J.E. Transmission of Bacterial Endophytes. Microorganisms 2017, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, N.; He, X.; Yang, H.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, H.; Huang, K. A novel endophytic bacterial strain improves potato storage characteristics by degrading glycoalkaloids and regulating microbiota. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 196, 112176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, D.; Squartini, A.; Crucitti, D.; Barizza, E.; Lo Schiavo, F.; Muresu, R.; Carimi, F.; Zottini, M. The role of the Endophytic Microbiome in the Grapevine Response to Environmental Triggers. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, H.L.; Tang, R.P.; Sun, M.Y.; Chen, T.M.; Duan, X.C.; Wang, S.Y. Pseudomonas putida represses JA- and SA-mediated defense pathways in rice and promotes an alternative defense mechanism possibly through ABA signaling. Plants 2020, 9, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, D.; Défago, G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Mitter, B.; Yousaf, S.; Pastar, M.; Afzal, M.; Sessitsch, A. The endophyte Enterobacter sp. FD17: A maize growth enhancer selected based on rigorous testing of plant beneficial traits and colonization characteristics. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2014, 50, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Reiter, B.; Sessitsch, A.; Nowak, J.; Clément, C.; Ait Barka, E. Endophytic colonization of Vitis vinifera L. by plant growth-promoting bacterium Burkholderia sp. strain PsJN. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, W.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, L.; Zhu, B. Beneficial Relationships Between Endophytic Bacteria and Medicinal Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 646146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Cambon, M.C.; Vacher, C.; Mitter, B.; Samad, A.; Sessitsch, A. The plant endosphere world–bacterial life within plants. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 1812–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.W.; Sibero, M.T.; Nadapdap, P.E. Bioprospecting for bacterial endophytes associated with zingiberaceae family rhizomes in Sibolangit forest, North Sumatera. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2020, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, G.; Kumar, A.; Babalola, O.O. The role of microbial seed endophytes in agriculture: Mechanisms and applications. Cereal Res. Commun. 2025, 53, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, N. Inoculant formulations are essential for successful inoculation with plant growth-promoting bacteria and business opportunities. Indian Phytopathol. 2016, 69, 739–743. [Google Scholar]

- Lebeis, S.L.; Paredes, S.H.; Lundberg, D.S.; Breakfield, N.; Gehring, J.; McDonald, M.; Malfatti, S.; del Rio, T.G.; Jones, C.D.; Tringe, S.G.; et al. Salicylic Acid Modulates Colonization of the Root Microbiome by Specific Bacterial Taxa. Science 2015, 349, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, B.O.; Medema, M.H.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Roadmap for Natural Product Discovery from Plant-Associated Microbiomes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2018, 82, e00035-18. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, G.; Rybakova, D.; Fischer, D.; Cernava, T.; Vergès, M.-C.C.; Charles, T.; Chen, X.; Cocolin, L.; Eversole, K.; Corral, G.H.; et al. Microbiome Definition Re-Visited: Old Concepts and New Challenges. Microbiome 2020, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernava, T. Coming of age for microbiome gene breeding in plants. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Endophyte Species | Host Plant | Activity/Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbacterium sp. | Arabis alpine | Under significant metal stress, produced phytohormones and enhanced plant development. | [88] |

| Sphingomonas, Steroidobacter and Actinoplanes | Nicotiana tabacum | Enhanced Cd stress resistance. | [89] |

| Enterobacter mori, E. ludwigii, E. cloacae, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, B. siamensis, Pseudomonas rhodesiae and Kosakonia oryzae | Oryza officinalis | Encouraged the development of robust root systems, biomass accumulation, chlorophyll content, and nitrogen uptake in plants. | [90] |

| Bacillus halotolerans | Solanum tuberosum | Antagonistic effect on pathogenic fungi and reduced the plant diseases and enhanced plant growth. | [91] |

| Curtobacterium oceanosedimentum, Curtobacterium luteum, Enterobacter ludwigii, Bacillus cereus, Micrococcus yunnanensis and Enterobacter tabaci | Oryza sativa | Produced a variety of phytohormones that reduced the negative effects of NaCl stress and improved rice development parameters. | [63] |

| Bacillus safensis | Nerium indicum | Drought protective effect. | [92] |

| Microbacterium albopurpureum | Chiloschista parishii | Plant growth promotion. | [93] |

| Bacillus velezensis, Bacillus megaterium and Herpaspirillum huttiense | Fragaria chiloensis | Serve as both a plant growth inducer and therapeutic nutrients to combat Rhizoctonia root rot disease. | [94] |

| Bacillus subtilis | Triticum aestivum | Reduced the toxic effects of cadmium stress. | [32] |

| Stenotrophomonas rhizophila | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | Reduced the disease index of Cucumber Fusarium wilt, promoted seed germination, enzyme activities and seedling growth. | [95] |

| Rahnella Victoriana and Bacillus paramycoides | Brassica napus | Enhanced the crop yields and alleviated arsenic accumulation. | [96] |

| Bacillus subtilis | Triticum aestivum | Resistance against greenbug aphid Schizaphis graminum. | [97] |

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis | Dendrobium officinale | Promoted plant growth and resistance to salt, drought and cadmium stress. | [38] |

| Bacillus subtilis | Stipa purpurea | Resistance towards high temperature, low temperature and ultraviolet stress. | [98] |

| Burkholderia sp. | Nicotiana tabacam | Resistance towards Ralstonia solanacearum, a bacterial pathogen causing bacterial wilt disease. | [99] |

| Pseudomonas oryzihabitans | Pelargonium graveolens | Significant rise in the secondary metabolite production and plant growth. | [100] |

| Salinicola salarius | Avicennia officinalis | By phosphate solubilization and the hormone (Indole 3-acetic acid) that promotes plant development, resistance to severe temperatures and salt tolerance is achieved. | [101] |

| Paenibacillus peoriae | Triticum aestivum | Enhanced plant growth and resistance towards phytopathogens such as Fusarium culmorum. | [102] |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa | Endostemon obtusifolius | Drought stress mitigation and plant growth enhancement effects. | [103] |

| Bacillus mycoides | Viburnum grandiflorum | Amelioration of heavy metals zinc and nickel stress. | [104] |

| Bacillus safensis | Raphanus sativus | Alleviated salt stress and increased plant yield. | [105] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sen, A.; Saji, J.; Faseela, P.; Zhang, C.; Mohanan, S.; Xia, Y. Exploring the Functional Roles of Endophytic Bacteria in Plant Stress Tolerance for Sustainable Agriculture: Diversity, Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges. Plants 2026, 15, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020206

Sen A, Saji J, Faseela P, Zhang C, Mohanan S, Xia Y. Exploring the Functional Roles of Endophytic Bacteria in Plant Stress Tolerance for Sustainable Agriculture: Diversity, Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges. Plants. 2026; 15(2):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020206

Chicago/Turabian StyleSen, Akhila, Johns Saji, Parammal Faseela, Chunquan Zhang, Shibin Mohanan, and Ye Xia. 2026. "Exploring the Functional Roles of Endophytic Bacteria in Plant Stress Tolerance for Sustainable Agriculture: Diversity, Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges" Plants 15, no. 2: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020206

APA StyleSen, A., Saji, J., Faseela, P., Zhang, C., Mohanan, S., & Xia, Y. (2026). Exploring the Functional Roles of Endophytic Bacteria in Plant Stress Tolerance for Sustainable Agriculture: Diversity, Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges. Plants, 15(2), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020206