Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Ormosia henryi Provides Insights into Evolutionary Resilience and Precision Conservation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

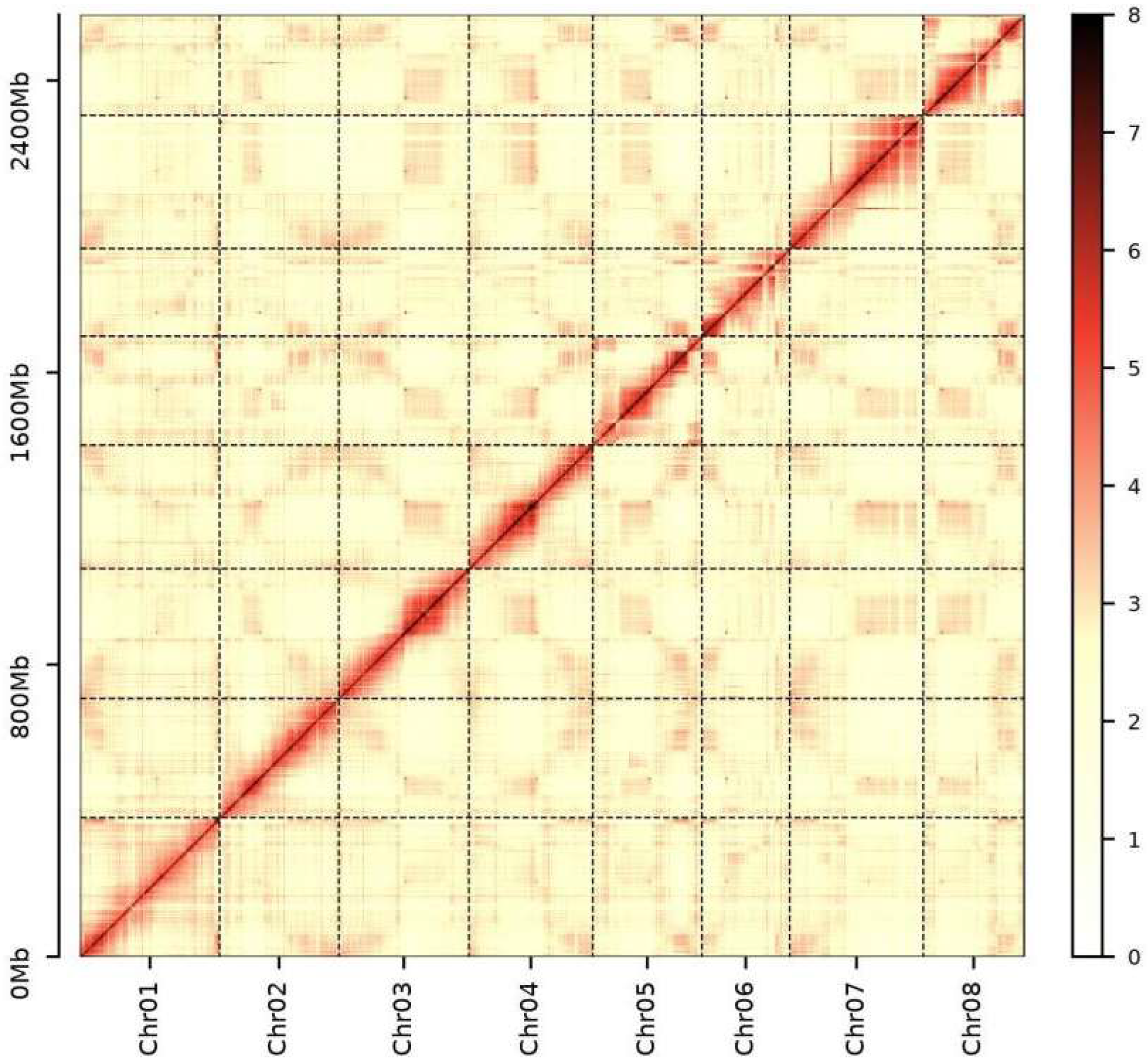

2.1. High-Quality Chromosome-Scale Genome Assembly

2.2. Genomic Features and Gene Annotation

2.3. Comparative Genomics and Evolutionary Insights

2.4. Synteny

3. Discussion

3.1. Genome Resource Significance

3.2. Evolutionary History and Its Implications for Conservation Genomics

3.3. Implications for Conservation and Sustainable Utilization

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Genomic Sequencing

4.3. Genome Assembly and Assessment

4.4. Gene Prediction and Annotation

4.5. Gene Family Clustering

4.6. Phylogeny

4.7. Gene Family Expansion/Contraction

4.8. Positive Selection

4.9. WGD Analysis

4.10. LTR Insertion Time

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, S.; Xu, B. Chromosome karyotype of Ormosia henryi. Trop. For. Sci. Technol. 1986, 2, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Q.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.H.; Feng, A.R.; Li, H.L.; Qaseem, M.F.; Liu, L.T.; Deng, X.M.; Wu, A.M. Integrative analysis of the metabolome and transcriptome reveals the molecular regulatory mechanism of isoflavonoid biosynthesis in Ormosia henryi Prain. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246, 125601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Wei, X.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y. Changes and transcriptome regulation of endogenous hormones during somatic embryogenesis in Ormosia henryi Prain. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1121259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.U.N.; Yangwen, D.U.; Xia, L.I.; Boyun, L.I.U.; Song, Y. Quantitative assessment of priority for conservation of the national protected plants in xuebaoshan nature reserve. J. Southwest Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2007, 29, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, M.; Wei, X. Spermosphere bacterial community at different germination stages of Ormosia henryi and its relationship with seed germination. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 324, 112608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xia, S.; Wen, Q.; Song, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wang, T.; Liu, L.; Ouyang, T. Genetic structure of an endangered species Ormosia henryi in southern China, and implications for conservation. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-P.; Wang, Z.-F.; Cheng, F.; Yu, E.-P.; Fu, L.; Zeng, Y.-N.; Huang, Y.-M.; Chen, X.-G.; Deng, S.-W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A chromosome-scale assembly of Ormosia boluoensis (Fabaceae). Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-F.; Yu, E.-P.; Fu, L.; Deng, H.-G.; Zhu, W.-G.; Xu, F.-X.; Cao, H.-L. Chromosome-scale assemblies of three Ormosia species: Repetitive sequences distribution and structural rearrangement. GigaScience 2025, 14, giaf047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-P.; Yu, E.-P.; Tan, Z.-J.; Sun, H.-M.; Zhu, W.-G.; Wang, Z.-F.; Cao, H.-L. Genome assemblies of two Ormosia species: Gene duplication related to their evolutionary adaptation. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wen, Q.; Zeng, D.; Guo, C.; Guo, Z.; Liu, L.; Ouyang, T. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the endangered tree species Ormosia henryi Prain. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, H.; Guo, H.; Xia, X.; Zhang, Z.; Nong, B.; Feng, R.; Liang, S.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; et al. Revealing Genomic Traits and Evolutionary Insights of Oryza officinalis from Southern China Through Genome Assembly and Transcriptome Analysis. Rice 2025, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Tian, K.; You, L.; Xie, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A chromosome-scale genome assembly and epigenomic profiling reveal temperature-dependent histone methylation in iridoid biosynthesis regulation in Scrophularia ningpoensis. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.-T.; Wang, Z.-L.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Ye, M.; Ye, C.-Y. A long road ahead to reliable and complete medicinal plant genomes. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Deng, N. Geometric morphologic variation Ormosia henryi prain leaves from different hunan provenances. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2024, 53, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yuan, W.; Chen, C.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, B. Preliminary Study on Growth Regularity of Man-made Ormosia henryi Forest. J. Zhejiang For. Sci. Technol. 2003, 23, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhan, X.; Gui, Z.; Liang, T.; Zhang, L.; Wan, M.; Du, J.; Nie, J. Community characteristics and spatial patterns of Ormosia henryi in Youling village of Jiangxi province. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2018, 38, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. Ecological characteristics of the populations of the precious tree species Ormosia henryi in Shaowu Jiangshi Provincial nature reserve. Chin. Wild Plant Resour. 2023, 42, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T. The Research on Seed Germination and Seedling Drought Resistanceof Ormosia henryi Prain from Different Provenances. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jia, Q.; Wen, Q.; Mo, X.; Liu, L. Prediction of potential distribution of Ormosia henryi in China under climate change. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2021, 36, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, F.; Climent, J.M.; Voltas, J. Phenotypic integration and life history strategies among populations of Pinus halepensis: An insight through structural equation modelling. Ann. Bot. 2019, 124, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yao, X.; Cao, B.; Zhang, B.; Lu, L.; Mao, P. A chromosome-level genome assembly of Styphnolobium japonicum combined with comparative genomic analyses offers insights on the evolution of flavonoid and lignin biosynthesis. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 187, 115336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.H.; Dong, C.J.; Zhang, Z.G.; Wang, X.L.; Shang, Q.M. Insights into salicylic acid responses in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) cotyledons based on a comparative proteomic analysis. Plant Sci. 2012, 187, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Geng, L.; Shuting, D.; Peng, L.; Jiwang, Z.; Bin, Z. Proteomic analysis of maize grain development using iTRAQ reveals temporal programs of diverse metabolic processes. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, R.C.; Begley, T.J.; Samson, L.D. Genome-wide responses to DNA-damaging agents. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 59, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Ye, Z.; Li, C.; Huang, S.; Lin, T. The genomic route to tomato breeding: Past, present, and future. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 2500–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; Sinha, P.; Singh, V.K.; Kumar, A.; Zhang, Q.; Bennetzen, J.L. 5Gs for crop genetic improvement. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 56, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, W.J.; Garcia-Robledo, C.; Uriarte, M.; Erickson, D.L. DNA barcodes for ecology, evolution, and conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgotra, R.K.; Chauhan, B.S. Genetic diversity, conservation, and utilization of plant genetic resources. Genes 2023, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, W.; Tian, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, B.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y. Population genetic variation and geographic distribution of suitable areas of Coptis species in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1341996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsumura, Y.; Uchiyama, K.; Moriguchi, Y.; Ueno, S.; Ihara-Ujino, T. Genome scanning for detecting adaptive genes along environmental gradients in the Japanese conifer, Cryptomeria japonica. Heredity 2012, 109, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrill, P.; Mago, R.; Xu, T.; Ford, B.; Williams, S.J.; Derkx, A.; Bovill, W.D.; Hyles, J.; Bhatt, D.; Xia, X.; et al. An autoactive NB-LRR gene causes Rht13 dwarfism in wheat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2209875119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistic | Scaffold | Contig |

|---|---|---|

| Total number | 361 | 537 |

| Total length of (bp) | 2,639,023,864 | 2,638,935,864 |

| Gap number (bp) | 586,000 | 0 |

| N50 length (bp) | 338,397,820 | 39,169,180 |

| N90 length (bp) | 240,162,212 | 9,385,987 |

| Maximum length (bp) | 380,859,801 | 148,418,790 |

| Minimum length (bp) | 240,162,212 | 9,385,987 |

| Type | Contig Level | Chromosome Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage (%) | Number | Percentage (%) | |

| Complete BUSCOs (C) | 1586 | 98.3 | 1587 | 98.3 |

| Complete and single-copy BUSCOs (S) | 1464 | 90.7 | 1464 | 90.7 |

| Complete and duplicated BUSCOs (D) | 122 | 7.6 | 123 | 7.6 |

| Fragmented BUSCOs (F) | 11 | 0.7 | 10 | 0.6 |

| Missing BUSCOs (M) | 17 | 1.0 | 17 | 1.1 |

| Total BUSCO groups searched | 1614 | - | 1614 | - |

| Database | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| GO_Annotation | 31,181 | 79.92 |

| KEGG_Annotation | 30,352 | 77.79 |

| KOG_Annotation | 22,984 | 58.91 |

| Pfam_Annotation | 32,964 | 84.49 |

| Swissprot_Annotation | 28,316 | 72.57 |

| TrEMBL_Annotation | 38,735 | 99.28 |

| eggNOG_Annotation | 33,323 | 85.41 |

| nr_Annotation | 38,532 | 98.76 |

| All_Annotated | 38,753 | 99.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, X.; Yuan, B.; Mou, C.; Xiang, G.; Zhu, L.; Li, G.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Hu, F.; Lv, H. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Ormosia henryi Provides Insights into Evolutionary Resilience and Precision Conservation. Plants 2026, 15, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020180

Tian X, Yuan B, Mou C, Xiang G, Zhu L, Li G, Liu C, Li X, Hu F, Lv H. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Ormosia henryi Provides Insights into Evolutionary Resilience and Precision Conservation. Plants. 2026; 15(2):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020180

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Xiaoming, Bin Yuan, Cun Mou, Guangfeng Xiang, Lu Zhu, Gaofei Li, Chao Liu, Xiangpeng Li, Fuliang Hu, and Hao Lv. 2026. "Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Ormosia henryi Provides Insights into Evolutionary Resilience and Precision Conservation" Plants 15, no. 2: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020180

APA StyleTian, X., Yuan, B., Mou, C., Xiang, G., Zhu, L., Li, G., Liu, C., Li, X., Hu, F., & Lv, H. (2026). Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Ormosia henryi Provides Insights into Evolutionary Resilience and Precision Conservation. Plants, 15(2), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020180