Effect of Foliar Biostimulant Application on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity in Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

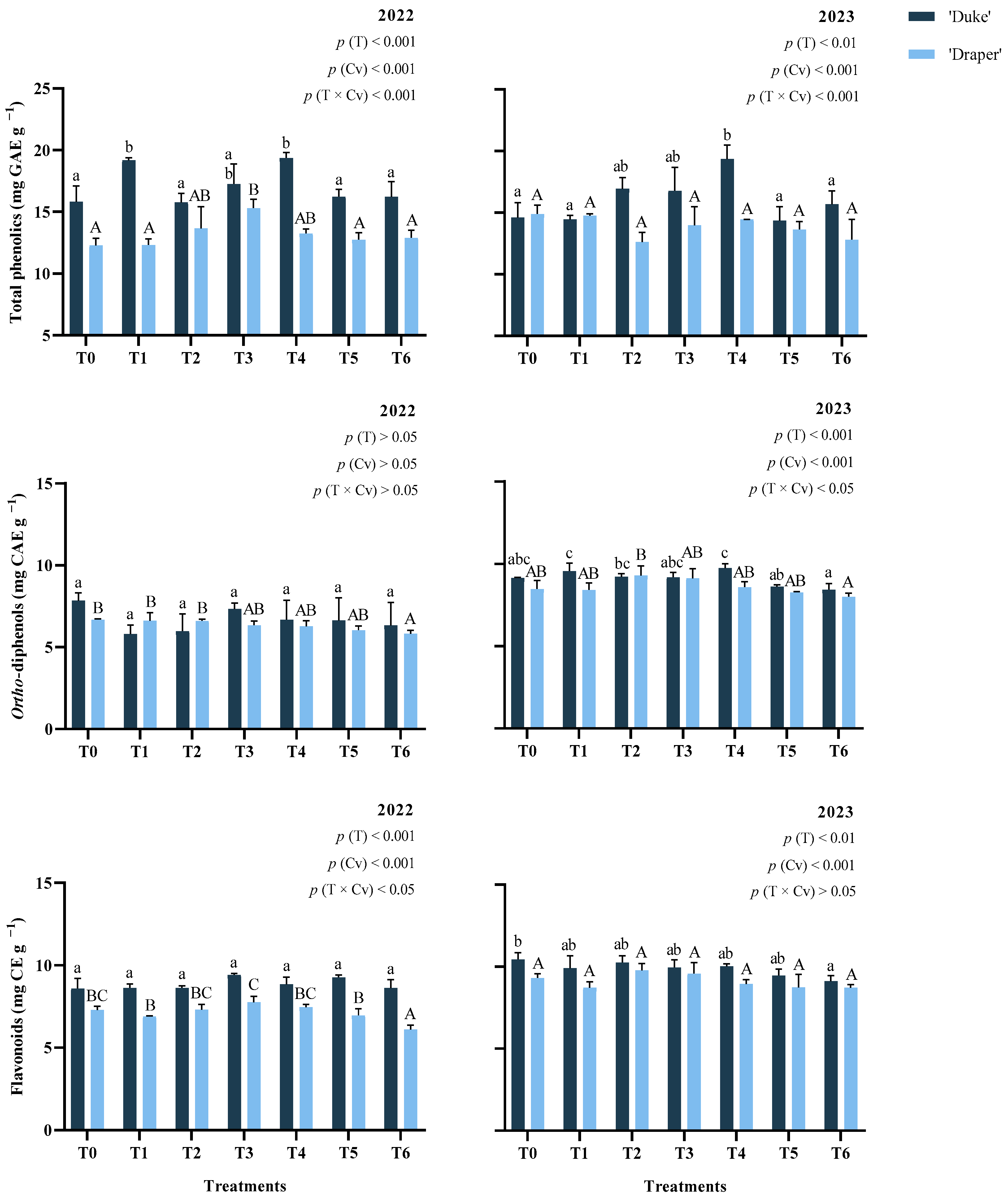

2.1. Total Phenolic Compounds, Flavonoids, and Ortho-Diphenols

2.2. Individual Phenolic Compounds Identified by HPLC

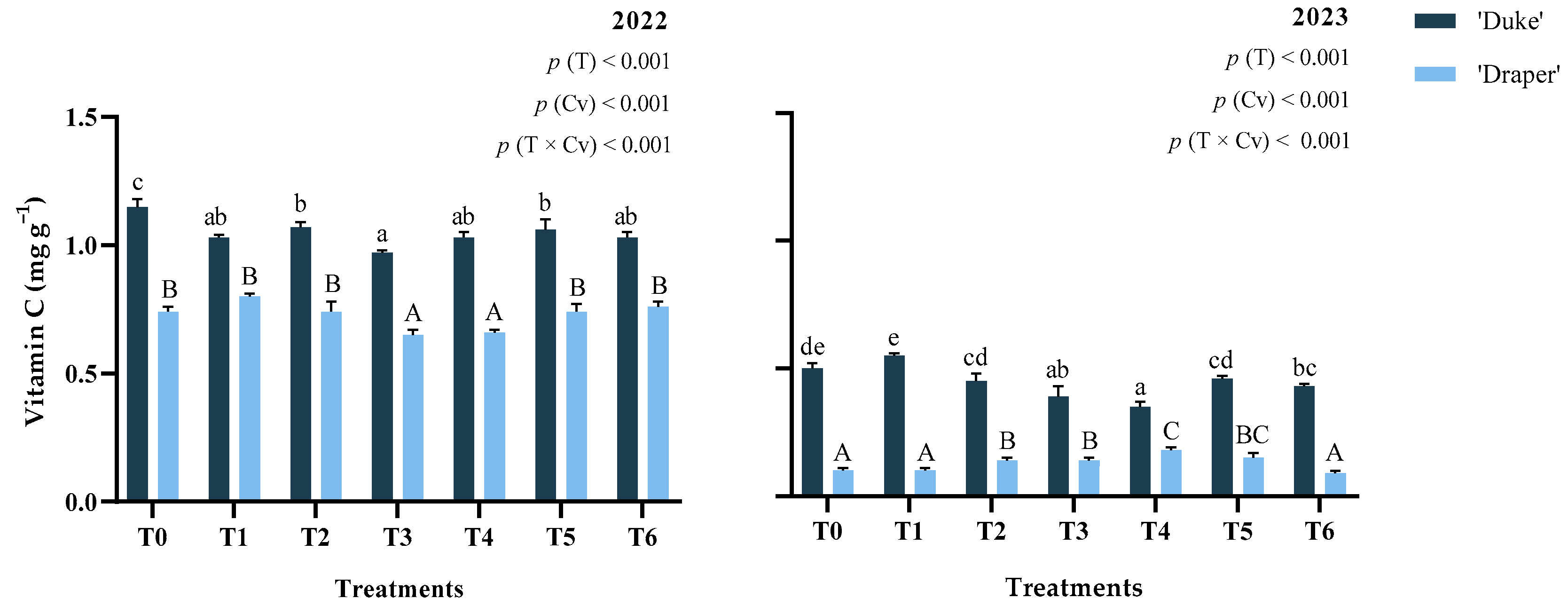

2.3. Vitamin C

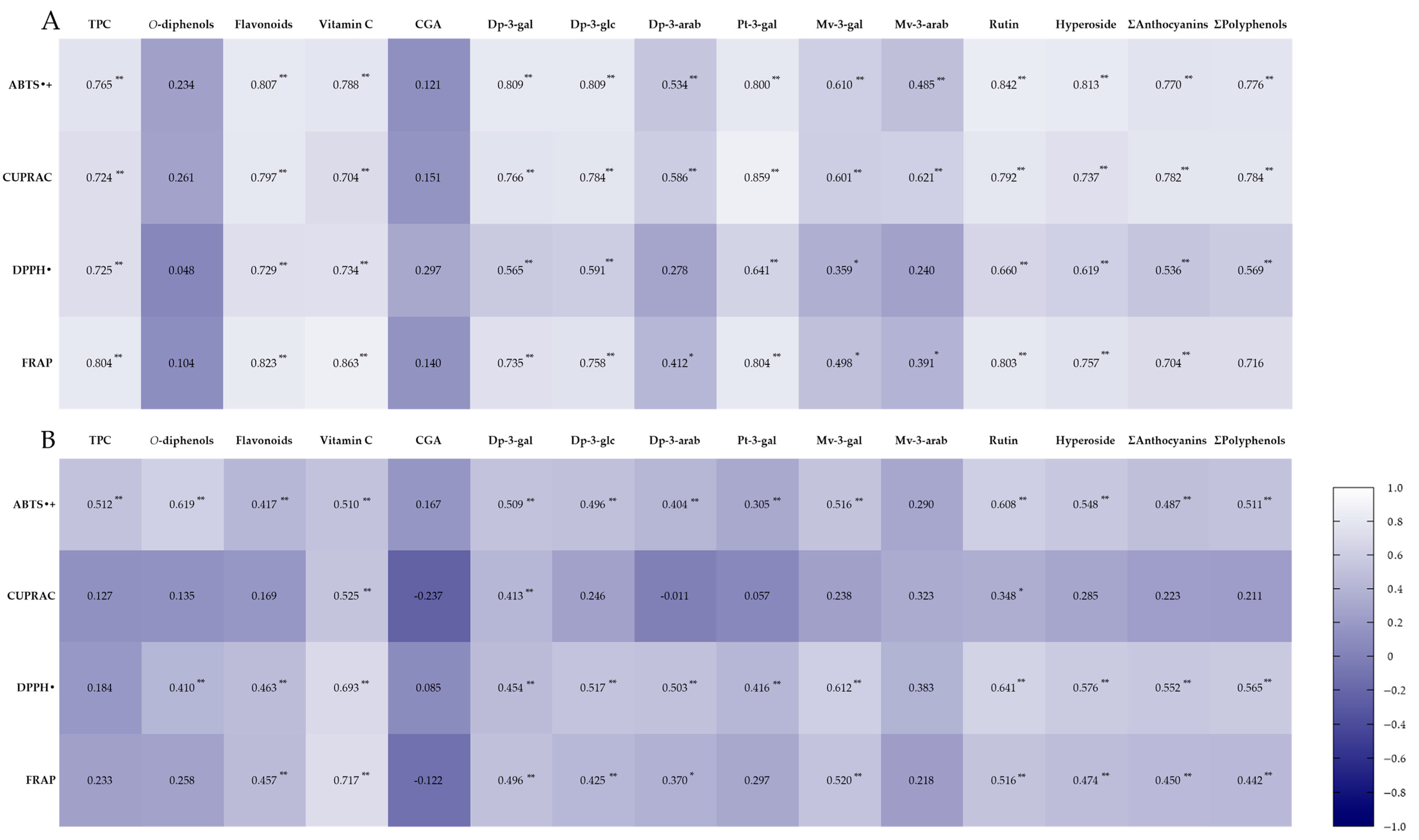

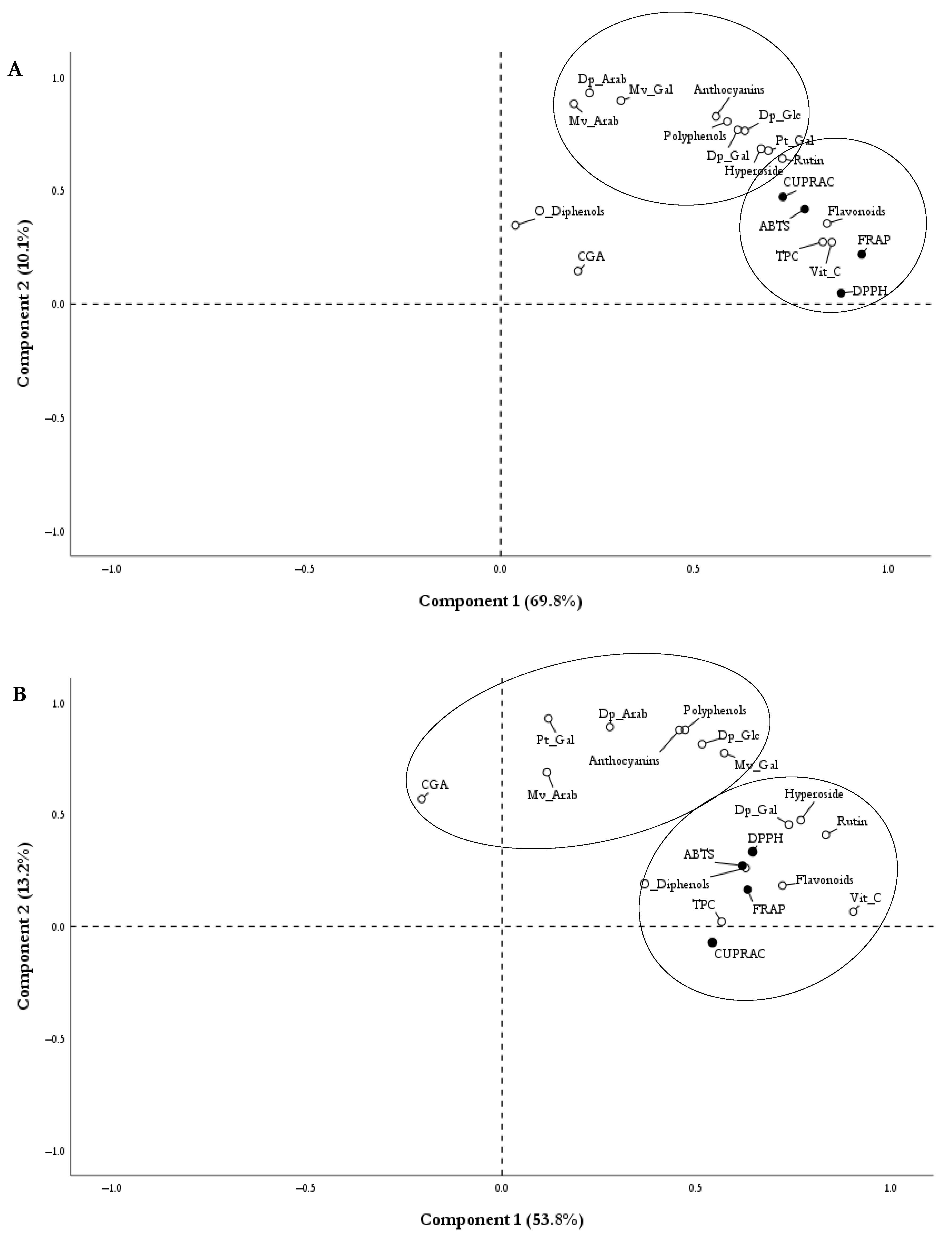

2.4. Antioxidant Capacity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material and Sampling

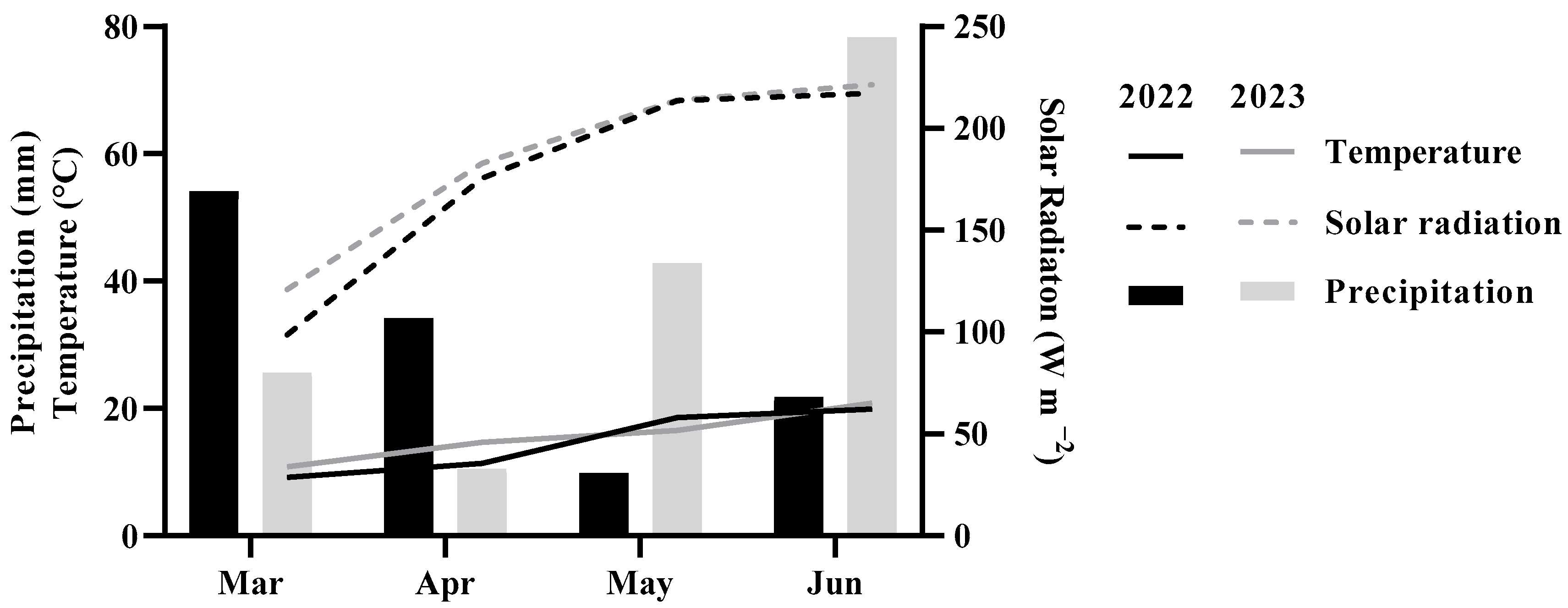

3.2. Climatic Conditions

3.3. Determination of Phenolic Compounds

3.3.1. Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC)

3.3.2. Ortho-Diphenols

3.3.3. Flavonoids

3.4. Individual Polyphenols

3.5. Determination of Vitamin C Content

3.6. Antioxidant Capacity Assays

3.6.1. ABTS•+ Radical-Scavenging Activity

3.6.2. Cupric-Reducing Antioxidant Capacity (CUPRAC)

3.6.3. DPPH• Radical-Scavenging Capacity

3.6.4. Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameters | p (T) | p (Cv) | p (Y) | p (T × Cv) | p (T × Y) | p (C × Y) | p (T × Cv × Y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Phenolic Compounds | <0.001 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Flavonoids | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.05 |

| Ortho-diphenols | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.001 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| Sum of Anthocyanins | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.001 |

| Sum of Individual Polyphenols | <0.001 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.01 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin C | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 |

| ABTS•+ | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CUPRAC | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| DPPH• | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | >0.05 | <0.001 |

| FRAP | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

References

- Gilbert, J.L.; Olmstead, J.W.; Colquhoun, T.A.; Levin, L.A.; Clark, D.G.; Moskowitz, H.R. Consumer-assisted selection of blueberry fruit quality traits. HortScience 2014, 49, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Costa, E.M.; Veiga, M.; Morais, R.M.; Calhau, C.; Pintado, M. Health-promoting properties of blueberries: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sater, H.; Ferrão, L.F.V.; Olmstead, J.; Munoz, P.R.; Bai, J.; Hopf, A.; Plotto, A. Exploring environmental and storage factors affecting sensory, physical, and chemical attributes of six southern highbush blueberry cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 289, 110468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Tarafdar, A.; Chaurasia, D.; Singh, A.; Bhargava, P.C.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Ni, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Blueberry fruit valorization and valuable constituents: A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 381, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gündüz, K.; Serçe, S.; Hancock, J.F. Variation among highbush and rabbiteye cultivars of blueberry for fruit quality and phytochemical characteristics. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 38, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.; Gonçalves, B.; Aires, A.; Silva, A.; Ferreira, L.; Carvalho, R.; Fernandes, H.; Freitas, C.; Carnide, V.; Paula Silva, A. Effect of harvest year and altitude on nutritional and biometric characteristics of blueberry cultivars. J. Chem. 2016, 2016, 8648609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenart, A.; Wrona, D.; Krupa, T. Health-promoting properties of highbush blueberries depending on type of fertilization. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radünz, A.L.; Herter, F.G.; Radünz, M.; Silva, V.N.D.; Cabrera, L.D.C.; Radünz, L.L. Bud position influences the fruit quality attributes of three blueberry (Vaccinium ashei Reade) cultivars. Rev. Ceres 2022, 69, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Jardin, P.; Xu, L.; Geelen, D. Agricultural functions and action mechanisms of plant biostimulants (PBS): An introduction. In The Chemical Biology of Plant Biostimulants, 1st ed.; Geelen, D., Xu, L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenart, A.; Wrona, D.; Krupa, T. Biostimulators with marine algae extracts and their role in increasing tolerance to drought stress in highbush blueberry cultivation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koort, A.; Starast, M.; Põldma, P.; Moor, U.; Mainla, L.; Maante-Kuljus, M.; Karp, K. Sustainable fertilizer strategies for Vaccinium corymbosum × V. angustifolium under abandoned peatland conditions. Agriculture 2020, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirk, W.A.; Rengasamy, K.R.R.; Kulkarni, M.G.; Van Staden, J. Plant biostimulants from seaweed: An overview. In The Chemical Biology of Plant Biostimulants, 1st ed.; Geelen, D., Xu, L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.H.H.; Murata, N. Glycinebetaine protects plants against abiotic stress: Mechanisms and biotechnological applications. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.; Baltazar, M.; Pereira, S.; Correia, S.; Ferreira, H.; Alves, F.; Cortez, I.; Castro, I.; Gonçalves, B. Ascophyllum nodosum extract and glycine betaine preharvest application in grapevine: Enhancement of berry quality, phytochemical content and antioxidant properties. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, S.; Oliveira, I.; Ribeiro, C.; Vilela, A.; Meyer, A.S.; Gonçalves, B. Exploring the role of biostimulants in sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) fruit quality traits. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.; Silva, A.P.; Ribeiro, C.; Carvalho, R.; Aires, A.; Vicente, A.A.; Gonçalves, B. Ecklonia maxima and glycine–betaine-based biostimulants improve blueberry yield and quality. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kou, X.; Zhang, G.; Luo, D.; Cao, S. Exogenous glycine betaine maintains postharvest blueberry quality by modulating antioxidant capacity and energy metabolism. LWT 2024, 212, 116976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consentino, B.B.; Vultaggio, L.; Iacuzzi, N.; La Bella, S.; De Pasquale, C.; Rouphael, Y.; Ntatsi, G.; Virga, G.; Sabatino, L. Iodine biofortification and seaweed extract-based biostimulant supply interactively drive the yield, quality, and functional traits in strawberry fruits. Plants 2023, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, H.; Dong, Y. Seaweed-based biostimulants improve quality traits, postharvest disorders, and antioxidant properties of sweet cherry fruit in response to gibberellic acid treatment. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 336, 113454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Debnath, P.; Singh, S.; Kumar, N. An Overview of Plant Phenolics and Their Involvement in Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Stresses 2023, 3, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Anmol, A.; Kumar, S.; Wani, A.W.; Bakshi, M.; Dhiman, Z. Exploring Phenolic Compounds as Natural Stress Alleviators in Plants—A Comprehensive Review. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 133, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naikoo, M.I.; Dar, M.I.; Raghib, F.; Jaleel, H.; Ahmad, B.; Raina, A.; Khan, F.A.; Naushin, F. Role and regulation of plant phenolics in abiotic stress tolerance. In Plant Signaling Molecules; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shan, T.; Xie, B.; Ling, C.; Shao, S.; Jin, P.; Zheng, Y. Glycine betaine reduces chilling injury in peach fruit by enhancing phenolic and sugar metabolisms. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.-L. Postharvest application of glycine betaine ameliorates chilling injury in cold-stored banana fruit by enhancing antioxidant system. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 287, 110264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulatory activities of Ascophyllum nodosum extract in tomato and sweet pepper crops in a tropical environment. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.; De Lorenzis, G.; Ricciardi, V.; Baltazar, M.; Pereira, S.; Correia, S.; Ferreira, H.; Alves, F.; Cortez, I.; Gonçalves, B.; et al. Exploring seaweed and glycine betaine biostimulants for enhanced phenolic content, antioxidant properties, and gene expression of Vitis vinifera cv. “Touriga Franca” berries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, B.; Karaca, C.; Sarıdaş, M.A.; Ağçam, E.; Çeliktopuz, E.; Kargı, S.P. Enhancing secondary compounds in strawberry fruit through optimized irrigation and seaweed application. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 324, 112609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, L.J.; Papageorgiou, A.E.; Setati, M.E.; Blancquaert, E.H. Effects of Ecklonia maxima seaweed extract on the fruit, wine quality, and microbiota in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cabernet Sauvignon. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 172, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, S.; Kunz, C.; Rudloff, S. Inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell migration by plasma anthocyanins isolated from healthy volunteers receiving an anthocyanin-rich berry juice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalt, W.; Cassidy, A.; Howard, L.R.; Krikorian, R.; Stull, A.J.; Tremblay, F.; Zamora-Ros, R. Recent research on the health benefits of blueberries and their anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Guo, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Xiao, X.; Wang, S.; Gong, P.; Ma, Y.; Chen, F. Structure and function of blueberry anthocyanins: A review of recent advances. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 88, 104864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni, T.; Sabbatini, P.; Tombesi, S.; Norrie, J.; Poni, S.; Gatti, M.; Palliotti, A. Effects of a biostimulant derived from the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum on ripening dynamics and fruit quality of grapevines. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 232, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, T.; Liu, M.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, G.; He, S.; Liao, L.; Xiong, B.; Wang, X.; et al. Effects of exogenous application of glycine betaine treatment on ‘Huangguoggan’ fruit during postharvest storage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.; Morais, M.C.; Sequeira, A.; Ribeiro, C.; Guedes, F.; Silva, A.P.; Aires, A. Quality preservation of sweet cherry cv. “Staccato” by using glycine-betaine or Ascophyllum nodosum. Food Chem. 2020, 322, 126713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Kader, A.A. Preharvest and postharvest factors influencing vitamin C content of horticultural crops. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2000, 20, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.; Aires, A.; Queirós, F.; Carvalho, R.; Schouten, R.; Silva, A.P.; Gonçalves, B. Climate conditions and spray treatments induce shifts in health-promoting compounds in cherry (Prunus avium L.) fruits. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 263, 109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Yu, X.; Kikuchi, A.; Asahina, M.; Watanabe, K.N. Genetic engineering of glycine betaine biosynthesis to enhance abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Biotechnol. 2009, 26, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, A.; Han, S.; Haider, M.Z.; Khizar, R.; Ali, Q.; Shafiq, M.; Tabassum, J.; Khalid, M.N.; Javed, M.A.; Sajid, M.; et al. Genetic aspects of vitamin C (ascorbic acid) biosynthesis and signaling pathways in fruits and vegetable crops. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2024, 24, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, M.; Hassan, S.M.; Elshobary, M.E.; Ammar, G.A.G.; Gaber, A.; Alsanie, W.F.; Mansour, A.T.; El-Shenody, R. Impact of commercial seaweed liquid extract (TAM®) biostimulant and its bioactive molecules on growth and antioxidant activities of hot pepper (Capsicum annuum). Plants 2021, 10, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, M.S.F.; Abedi, B.; Ne’emati, S.H.; Arouiee, H. Studying the effects of foliar spraying of seaweed extract as a biostimulant on the increase in the yield and quality of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.). World J. Environ. Biosci. 2014, 8, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Adak, N. Effects of glycine betaine concentrations on the agronomic characteristics of strawberry grown under deficit irrigation conditions. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 3753–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardeñosa, V.; Girones-Vilaplana, A.; Muriel, J.L.; Moreno, D.A.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Influence of genotype, cultivation system and irrigation regime on antioxidant capacity and selected phenolics of blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L.). Food Chem. 2016, 202, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, A.; Kalisz, A.; Sękara, A. Seaweed extracts’ multifactorial action: Influence on physiological and biochemical status of Solanaceae plants. Acta Agrobot. 2019, 72, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S.; Kumar, G.; Hussain, S. Utilization of seaweed-based biostimulants in improving plant and soil health: Current updates and future prospective. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 12839–12852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujeeth, N.; Petrov, V.; Guinan, K.J.; Rasul, F.; O’Sullivan, J.T.; Gechev, T.S. Current insights into the molecular mode of action of seaweed-based biostimulants and the sustainability of seaweeds as raw material resources. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, F.; Valero, D.; Serrano, M.; Guillén, F. Exogenous application of glycine betaine maintains bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity, and physicochemical attributes of blood orange fruit during prolonged cold storage. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 873915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Trivedi, K.; Anand, K.G.V.; Ghosh, A. Science behind biostimulant action of seaweed extract on growth and crop yield: Insights into transcriptional changes in roots of maize treated with Kappaphycus alvarezii seaweed extract under soil moisture stressed conditions. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, G.; Campobenedetto, C.; Vigliante, I.; Contartese, V.; Gentile, C.; Bertea, C.M. The application of a plant biostimulant based on seaweed and yeast extract improved tomato fruit development and quality. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichura, M.A.; Koschnick, F.; Jung, J.; Bauer, S.; Wichura, A. Phenological growth stages of highbush blueberries (Vaccinium spp.): Codification and description according to the BBCH scale. Botany 2024, 102, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic–phosphotungstic acid reagent. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewanto, V.; Wu, X.; Adom, K.K.; Liu, R.H. Thermal Processing Enhances the Nutritional Value of Tomatoes by Increasing Total Antioxidant Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3010–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutfinger, T. Polyphenols in olive oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1981, 58, 966–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, B.; Coelho, J.; Costa, M.; Pinto, J.; Paiva-Martins, F. A simple method for the determination of bioactive anti-oxidants in virgin olive oils. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 1727–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires, A.; Carvalho, R.; Rosa, E.A.S.; Saavedra, M.J. Phytochemical characterization and antioxidant properties of baby-leaf watercress produced under organic production system. CyTA J. Food 2013, 11, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, Y.; Lobo, M.G.; Gonzalez, M. Determination of vitamin C in tropical fruits: A comparative evaluation of methods. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires, A.; Carvalho, R.; Matos, M.; Carnide, V.; Silva, A.P.; Gonçalves, B. Variation of chemical constituents, anti-oxidant activity, and endogenous plant hormones throughout different ripening stages of highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) cultivars produced in centre of Portugal. J. Food Biochem. 2017, 41, e12414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratil, P.; Klejdus, B.; Kubán, V. Determination of total content of phenolic compounds and their antioxidant activity in vegetables—Evaluation of spectrophotometric methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Özyürek, M.; Karademir, S.E. Novel total antioxidant capacity index for dietary polyphenols and vitamins C and E, using their cupric ion reducing capability in the presence of neocuproine: CUPRAC method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7970–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddhuraju, P.; Becker, K. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of total phenolic constituents from three different agroclimatic origins of drumstick tree (Moringa oleifera Lam) leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2144–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Years | Chlorogenic Acid | Delphinidin-3-O-galactoside | Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside | Delphinidin-3-O-arabinoside | Petunidin-3-O-galactoside | Malvidin-3-O-galactoside | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ||

| T0 | 2022 | 312.92 ± 7.02 ab | 305.97 ± 11.38 AB | 1059.47 ± 115.62 b | 625.71 ± 12.18 A | 858.09 ± 99.31 b | 513.18 ± 10.08 A | 535.06 ± 61.89 b | 378.26 ± 8.25 A | 626.64 ± 68.75 ab | 392.64 ± 8.99 AB | 347.77 ± 40.20 a | 247.45 ± 8.44 A |

| 2023 | 503.61 ± 5.82 a | 547.27 ± 12.39 A | 975.48 ± 29.61 b | 702.77 ± 25.78 A | 783.27 ± 11.44 c | 599.50 ± 17.43 A | 472.41 ± 22.41 b | 341.57 ± 8.78 ABC | 438.03 ± 22.69 bc | 397.31 ± 16.55 AB | 341.83 ± 9.16 bc | 235.31 ± 9.63 A | |

| T1 | 2022 | 356.32 ± 7.29 bc | 376.13 ± 41.08 BC | 889.01 ± 2.23 ab | 737.12 ± 46.81 ABC | 744.40 ± 0.80 ab | 610.48 ± 39.47 AB | 466.80 ± 1.77 ab | 452.35 ± 25.07 BC | 609.36 ± 15.60 ab | 508.63 ± 28.68 B | 311.82 ± 3.03 a | 285.87 ± 10.62 AB |

| 2023 | 621.34 ± 16.37 b | 519.59 ± 20.08 A | 858.86 ± 56.40 a | 711.13 ± 34.96 A | 754.37 ± 56.73 c | 594.92 ± 36.06 A | 541.17 ± 54.43 b | 310.60 ± 20.67 AB | 489.93 ± 36.86 cd | 398.49 ± 17.21 AB | 338.99 ± 25.37 bc | 237.84 ± 22.38 A | |

| T2 | 2022 | 392.79 ± 27.31 c | 422.60 ± 62.23 C | 821.88 ± 10.34 a | 658.44 ± 25.23 AB | 686.90 ± 15.05 a | 551.66 ± 25.27 A | 404.83 ± 14.40 a | 389.21 ± 12.90 AB | 528.87 ± 7.48 a | 461.57 ± 21.36 ABC | 283.65 ± 6.03 a | 255.53 ± 13.57 A |

| 2023 | 502.61 ± 61.38 a | 567.43 ± 38.82 A | 761.91 ± 10.39 a | 696.90 ± 86.44 A | 676.35 ± 15.58 abc | 576.42 ± 83.04 A | 473.44 ± 11.58 b | 302.10 ± 39.44 B | 508.06 ± 5.57 cd | 335.00 ± 38.52 A | 326.09 ± 13.27 bc | 233.59 ± 37.51 A | |

| T3 | 2022 | 369.32 ± 19.71 c | 365.17 ± 29.54 ABC | 927.79 ± 48.87 ab | 809.15 ± 29.54 C | 795.28 ± 45.99 ab | 681.19 ± 24.39 B | 487.04 ± 38.85 ab | 481.78 ± 13.68 C | 641.47 ± 32.06 b | 505.40 ± 31.30 C | 339.14 ± 23.47 a | 326.26 ± 18.78 B |

| 2023 | 552.30 ± 24.23 ab | 572.05 ± 14.70 A | 866.86 ± 64.57 ab | 780.92 ± 47.35 A | 775.76 ± 46.69 c | 695.70 ± 25.98 A | 546.43 ± 44.70 b | 419.47 ± 17.13 C | 570.33 ± 41.16 d | 501.40 ± 13.07 C | 359.61 ± 12.42 c | 270.92 ± 13.85 A | |

| T4 | 2022 | 379.81 ± 17.87 c | 333.11 ± 13.05 ABC | 919.28 ± 79.90 ab | 722.97 ± 93.80 AB | 767.90 ± 71.56 ab | 599.12 ± 90.69 AB | 487.28 ± 40.82 ab | 405.39 ± 47.94 AB | 589.99 ± 45.26 ab | 414.97 ± 56.57 AB | 308.34 ± 25.95 a | 285.04 ± 28.63 AB |

| 2023 | 547.03 ± 37.10 ab | 565.86 ± 32.05 A | 827.04 ± 38.39 a | 681.96 ± 55.06 A | 690.96 ± 72.44 bc | 592.76 ± 61.64 A | 441.86 ± 104.35 b | 374.09 ± 48.56 ABC | 434.37 ± 76.64 bc | 438.91 ± 44.54 BC | 298.65 ± 30.27 b | 244.94 ± 34.23 A | |

| T5 | 2022 | 395.68 ± 28.92 c | 320.85 ± 19.08 AB | 934.54 ± 39.06 ab | 760.98 ± 35.24 BC | 772.69 ± 33.34 ab | 620.78 ± 23.33 AB | 465.58 ± 27.42 ab | 454.72 ± 29.06 BC | 614.93 ± 15.67 ab | 463.65 ± 24.71 BC | 303.01 ± 21.81 a | 287.15 ± 3.73 AB |

| 2023 | 514.08 ± 15.97 a | 569.99 ± 47.21 A | 772.80 ± 22.81 a | 686.79 ± 62.30 A | 592.51 ± 17.66 ab | 608.93 ± 59.99 A | 215.55 ± 43.07 a | 389.57 ± 24.38 BC | 355.38 ± 23.09 ab | 427.22 ± 30.68 BC | 227.15 ± 19.52 a | 237.80 ± 22.69 A | |

| T6 | 2022 | 291.00 ± 13.85 a | 270.85 ± 34.93 A | 853.34 ± 61.81 a | 651.44 ± 26.92 AB | 717.18 ± 48.28 ab | 546.88 ± 21.94 B | 437.34 ± 28.70 ab | 404.83 ± 15.93 AB | 599.71 ± 49.04 ab | 376.11 ± 20.84 A | 297.87 ± 26.15 a | 271.48 ± 10.52 A |

| 2023 | 510.36 ± 28.57 a | 506.65 ± 47.57 A | 791.19 ± 26.50 a | 716.84 ± 43.92 A | 569.56 ± 7.34 a | 627.69 ± 33.09 A | 169.84 ± 2.93 a | 357.80 ± 29.26 ABC | 291.21 ± 8.98 a | 444.47 ± 27.11 BC | 209.88 ± 5.24 a | 247.40 ± 20.97 A | |

| p(T) | 2022 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 2023 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| p(Cv) | 2022 | >0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 2023 | >0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.001 | |||||||

| p(T × Cv) | 2022 | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 | ||||||

| 2023 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Treatments | Years | Malvidin-3-O-arabinoside | Rutin | Hyperoside | Sum of Anthocyanins | Sum of Individual Polyphenols | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Duke’ | ‘Dr aper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ||

| T0 | 2022 | 458.56 ± 50.19 b | 358.13 ± 4.24 A | 334.50 ± 45.63 b | 181.33 ± 4.66 AB | 46.69 ± 8.02 b | 26.21 ± 0.84 A | 3.89 ± 0.43 b | 2.52 ± 0.05 A | 4.58 ± 0.48 b | 3.03 ± 0.05 A |

| 2023 | 368.81 ± 4.06 ab | 366.52 ± 7.77 AB | 303.58 ± 13.80 cd | 211.04 ± 11.16 A | 51.69 ± 2.58 c | 35.04 ± 2.51 A | 3.38 ± 0.08 c | 2.64 ± 0.08 AB | 4.24 ± 0.08 c | 3.44 ± 0.11 AB | |

| T1 | 2022 | 455.32 ± 4.04 b | 465.24 ± 17.07 C | 277.36 ± 0.19 ab | 191.69 ± 7.89 ABC | 40.77 ± 0.26 ab | 27.62 ± 1.70 A | 3.48 ± 0.03 ab | 3.06 ± 0.16 BC | 4.15 ± 0.03 ab | 3.66 ± 0.21 B |

| 2023 | 449.66 ± 42.17 bc | 386.63 ± 20.45 AB | 314.30 ± 24.92d | 223.24 ± 6.14 A | 49.85 ± 5.49 bc | 36.38 ± 1.26 A | 3.44 ± 0.27 c | 2.64 ± 0.15 AB | 4.43 ± 0.31 c | 3.42 ± 0.17 AB | |

| T2 | 2022 | 381.63 ± 5.83 a | 407.18 ± 21.93 ABC | 262.13 ± 4.25 a | 179.29 ± 11.06 A | 35.69 ± 1.77 a | 26.62 ± 1.70 A | 3.10 ± 0.04 a | 2.72 ± 0.12 AB | 3.79 ± 0.05 a | 3.35 ± 0.17 AB |

| 2023 | 445.03 ± 7.29 bc | 313.27 ± 45.91 A | 252.47 ± 2.37 ab | 199.74 ± 23.20 A | 40.61 ± 0.65 ab | 32.99 ± 4.49 A | 3.19 ± 0.06 c | 2.45 ± 0.33 A | 3.99 ± 0.11 bc | 3.25 ± 0.39 A | |

| T3 | 2022 | 478.61 ± 30.11 b | 448.31 ± 22.55 BC | 296.45 ± 13.57 ab | 248.35 ± 10.20D | 40.88 ± 1.98 ab | 36.09 ± 1.08 B | 3.67 ± 0.22 ab | 3.25 ± 0.14 C | 4.38 ± 0.25 ab | 3.90 ± 0.11 B |

| 2023 | 489.92 ± 45.05 c | 490.00 ± 13.34 C | 266.78 ± 20.12 abc | 226.21 ± 11.80 A | 43.77 ± 5.14 abc | 38.56 ± 2.25 A | 3.61 ± 0.25 c | 3.16 ± 0.08 B | 4.47 ± 0.30 c | 4.00 ± 0.08 B | |

| T4 | 2022 | 425.98 ± 29.23 ab | 386.79 ± 46.08 AB | 313.38 ± 24.39 ab | 218.98 ± 18.69 CD | 42.24 ± 4.59 ab | 30.37 ± 3.08 A | 3.50 ± 0.29 ab | 2.81 ± 0.35 ABC | 4.23 ± 0.33 ab | 3.40 ± 0.38 AB |

| 2023 | 356.46 ± 49.79 a | 396.14 ± 41.32 AB | 283.69 ± 8.41 bcd | 203.81 ± 21.38 A | 46.19 ± 2.00 bc | 33.21 ± 5.63 A | 3.05 ± 0.36 bc | 2.73 ± 0.28 AB | 3.93 ± 0.37 bc | 3.53 ± 0.34 AB | |

| T5 | 2022 | 448.53 ± 17.92 ab | 407.06 ± 18.41 ABC | 302.33 ± 14.05 ab | 211.18 ± 11.47 BC | 40.71 ± 1.53 ab | 29.40 ± 0.54 A | 3.54 ± 0.15 ab | 2.99 ± 0.13 ABC | 4.28 ± 0.16 ab | 3.56 ± 0.15 AB |

| 2023 | 416.40 ± 7.02 abc | 379.47 ± 27.45 AB | 255.46 ± 11.93 ab | 201.86 ± 15.97 A | 40.33 ± 1.21 ab | 32.22 ± 4.24 A | 2.58 ± 0.12 ab | 2.73 ± 0.22 AB | 3.39 ± 0.12 ab | 3.53 ± 0.29 AB | |

| T6 | 2022 | 430.81 ± 26.91 ab | 359.18 ± 22.07 A | 265.45 ± 20.06 a | 181.23 ± 6.87 AB | 35.01 ± 2.71 a | 25.80 ± 1.56 A | 3.34 ± 0.24 ab | 2.61 ± 0.11 AB | 3.93 ± 0.27 ab | 3.09 ± 0.14 AB |

| 2023 | 403.93 ± 7.32 ab | 409.25 ± 31.93 BC | 226.16 ± 21.84 a | 199.82 ± 11.49 A | 35.13 ± 3.97 a | 32.67 ± 1.16 A | 2.44 ± 0.04 a | 2.80 ± 0.18 AB | 3.21 ± 0.09 a | 3.54 ± 0.22 AB | |

| p(T) | 2022 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||

| 2023 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| p(Cv) | 2022 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| 2023 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| p(T × Cv) | 2022 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||

| 2023 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Treatments | Years | ABTS•+ (μmol L−1 TE g−1) | CUPRAC (μmol L−1 TE g−1) | DPPH• (μmol L−1 TE g−1) | FRAP (μmol L−1 FeSO4 g−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ‘Duke’ | ‘Draper’ | ||

| T0 | 2022 | 149.89 ± 13.12 ab | 86.03 ± 3.40 A | 119.48 ± 5.02 b | 88.49 ± 0.35 A | 82.60 ± 9.29 a | 77.21 ± 0.19 B | 178.69 ± 0.11 a | 151.25 ± 1.36 AB |

| 2023 | 176.50 ± 5.38 abc | 169.53 ± 1.43 AB | 72.60 ± 4.13 b | 60.57 ± 10.75 A | 118.47 ± 2.61 a | 95.57 ± 2.86 A | 96.01 ± 2.83 c | 81.19 ± 3.57 A | |

| T1 | 2022 | 154.24 ± 0.38 b | 100.90 ± 1.83 BC | 118.27 ± 2.10 b | 101.27 ± 2.77 BC | 91.86 ± 3.42 a | 66.12 ± 8.85 AB | 187.49 ± 0.54 abc | 145.64 ± 3.94 A |

| 2023 | 196.32 ± 0.78 d | 176.16 ± 3.77 B | 72.57 ± 0.16 b | 64.89 ± 3.77 A | 146.65 ± 5.83 b | 104.18 ± 5.04 A | 91.47 ± 1.69 abc | 81.53 ± 1.58 A | |

| T2 | 2022 | 128.10 ± 4.94 a | 91.36 ± 0.75 AB | 100.88 ± 2.20 a | 100.70 ± 4.05 BC | 97.09 ± 3.14 a | 71.44 ± 6.63 AB | 180.64 ± 1.61 ab | 154.43 ± 4.58 AB |

| 2023 | 176.18 ± 8.87 ab | 172.40 ± 4.65 AB | 72.92 ± 2.49 b | 69.99 ± 0.86 A | 133.90 ± 6.13 ab | 102.42 ± 11.57 A | 95.05 ± 1.80 bc | 83.95 ± 2.68 A | |

| T3 | 2022 | 142.35 ± 8.15 ab | 110.87 ± 1.62 CD | 128.39 ± 4.35 c | 107.24 ± 6.45 C | 97.11 ± 0.70 a | 73.90 ± 5.54 AB | 183.69 ± 3.17 abc | 159.03 ± 0.24 B |

| 2023 | 189.58 ± 0.16 bcd | 176.85 ± 7.42 B | 81.01 ± 0.43 c | 66.82 ± 7.00 A | 119.55 ± 18.15 a | 109.91 ± 2.88 A | 92.34 ± 1.13 abc | 85.49 ± 1.83 A | |

| T4 | 2022 | 134.85 ± 11.02 ab | 117.69 ± 7.86 D | 123.92 ± 1.16 bc | 99.33 ± 4.45 BC | 95.71 ± 4.58 a | 62.90 ± 2.14 AB | 181.95 ± 5.68 ab | 147.00 ± 6.43 A |

| 2023 | 190.03 ± 5.51 cd | 170.83 ± 8.80 AB | 62.81 ± 0.16 a | 57.50 ± 4.66 A | 108.73 ± 9.16 a | 96.21 ± 6.24 A | 87.10 ± 1.74 a | 84.71 ± 4.67 A | |

| T5 | 2022 | 143.80 ± 3.61 ab | 107.51 ± 3.38 CD | 130.29 ± 1.76 c | 101.08 ± 2.13 BC | 98.13 ± 3.48 a | 60.20 ± 5.34 A | 194.76 ± 4.29 c | 147.07 ± 4.04 A |

| 2023 | 167.15 ± 4.98 a | 157.08 ± 4.77 A | 80.42 ± 0.71 c | 55.61 ± 13.36 A | 109.48 ± 4.44 a | 104.43 ± 6.67 A | 90.29 ± 2.12 ab | 93.37 ± 1.95 B | |

| T6 | 2022 | 137.02 ± 9.75 ab | 91.16 ± 3.00 AB | 129.54 ± 3.50 c | 92.59 ± 0.71 AB | 81.89 ± 16.96 a | 75.06 ± 2.42 B | 190.64 ± 7.16 bc | 158.60 ± 1.07 B |

| 2023 | 182.30 ± 2.19 bc | 169.35 ± 4.92 AB | 75.44 ± 5.16 bc | 72.41 ± 2.88 A | 108.83 ± 8.07 a | 106.21 ± 2.03 A | 88.74 ± 1.42 a | 84.33 ± 0.58 A | |

| p(T) | 2022 | <0.001 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | ||||

| 2023 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.01 | |||||

| p(Cv) | 2022 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 2023 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| p(T × Cv) | 2022 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.001 | ||||

| 2023 | >0.05 | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lopes, T.; Silva, A.P.; Aires, A.; Carvalho, R.; Ferreira, M.; Vicente, A.A.; Gonçalves, B. Effect of Foliar Biostimulant Application on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity in Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.). Plants 2026, 15, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010092

Lopes T, Silva AP, Aires A, Carvalho R, Ferreira M, Vicente AA, Gonçalves B. Effect of Foliar Biostimulant Application on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity in Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.). Plants. 2026; 15(1):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010092

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopes, Tiago, Ana Paula Silva, Alfredo Aires, Rosa Carvalho, Maria Ferreira, António A. Vicente, and Berta Gonçalves. 2026. "Effect of Foliar Biostimulant Application on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity in Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.)" Plants 15, no. 1: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010092

APA StyleLopes, T., Silva, A. P., Aires, A., Carvalho, R., Ferreira, M., Vicente, A. A., & Gonçalves, B. (2026). Effect of Foliar Biostimulant Application on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity in Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.). Plants, 15(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010092