Effects of Polyethylene and Polystyrene Microplastics on Oat (Avena sativa L.) Growth and Physiological Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

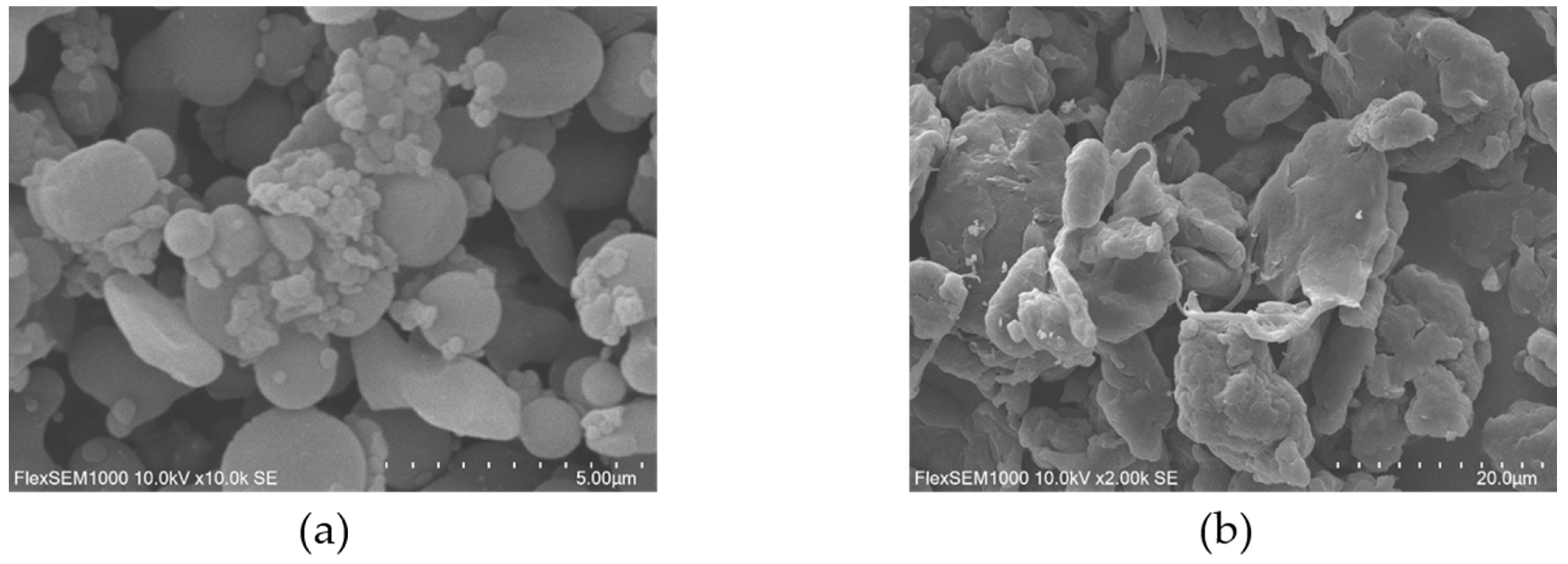

2.1. Morphological Characteristics of Microplastics

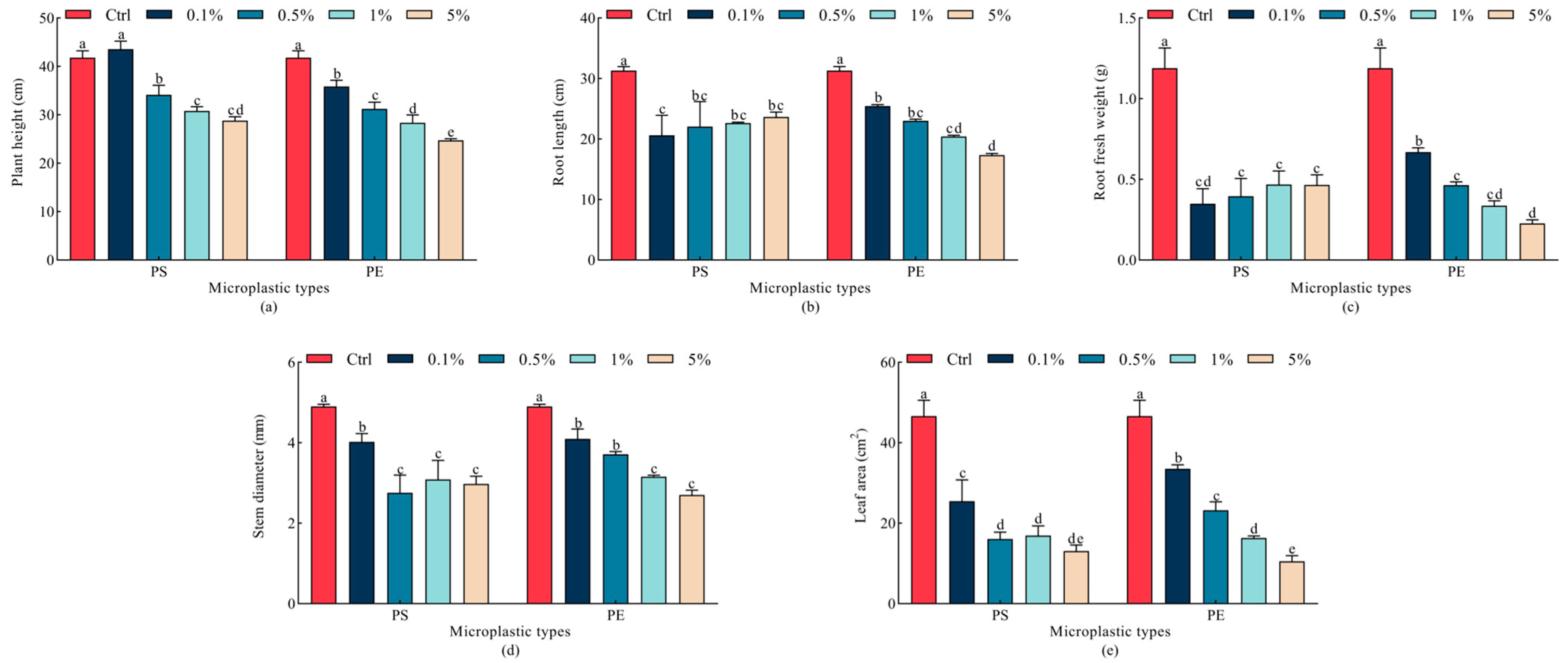

2.2. Effects of Microplastics on Oat Seedling Growth

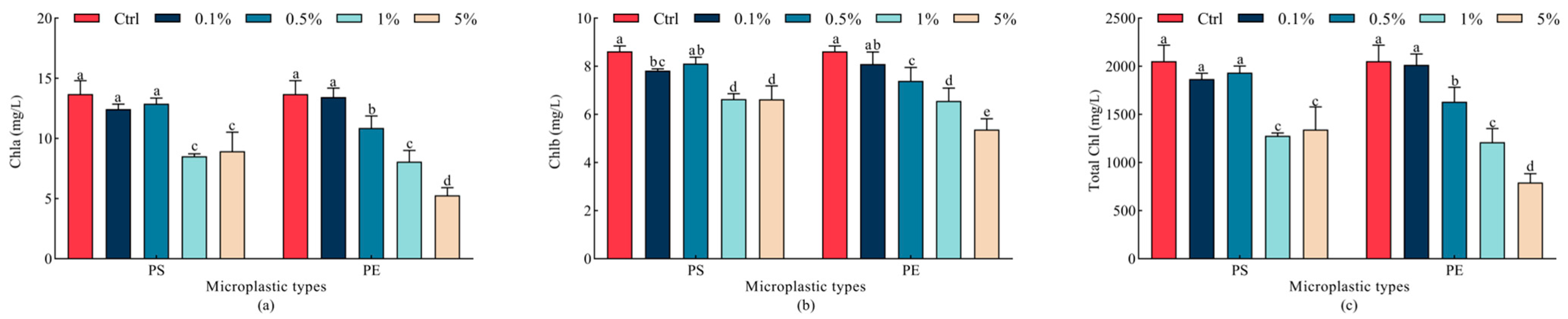

2.3. Effects of Microplastics on Chlorophyll Content in Oat Leaves

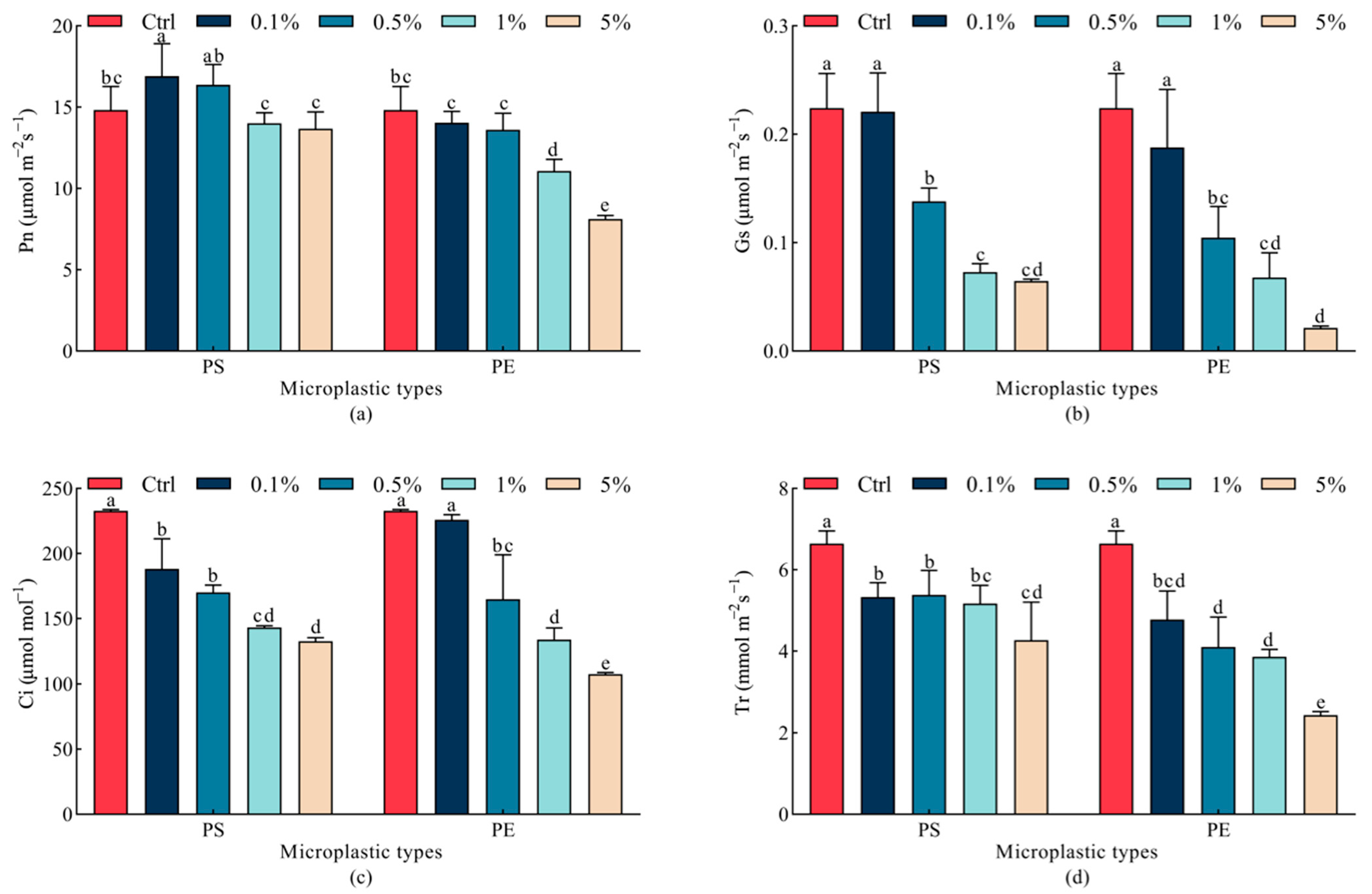

2.4. Effects of Microplastics on Photosynthetic Parameters in Oat Leaves

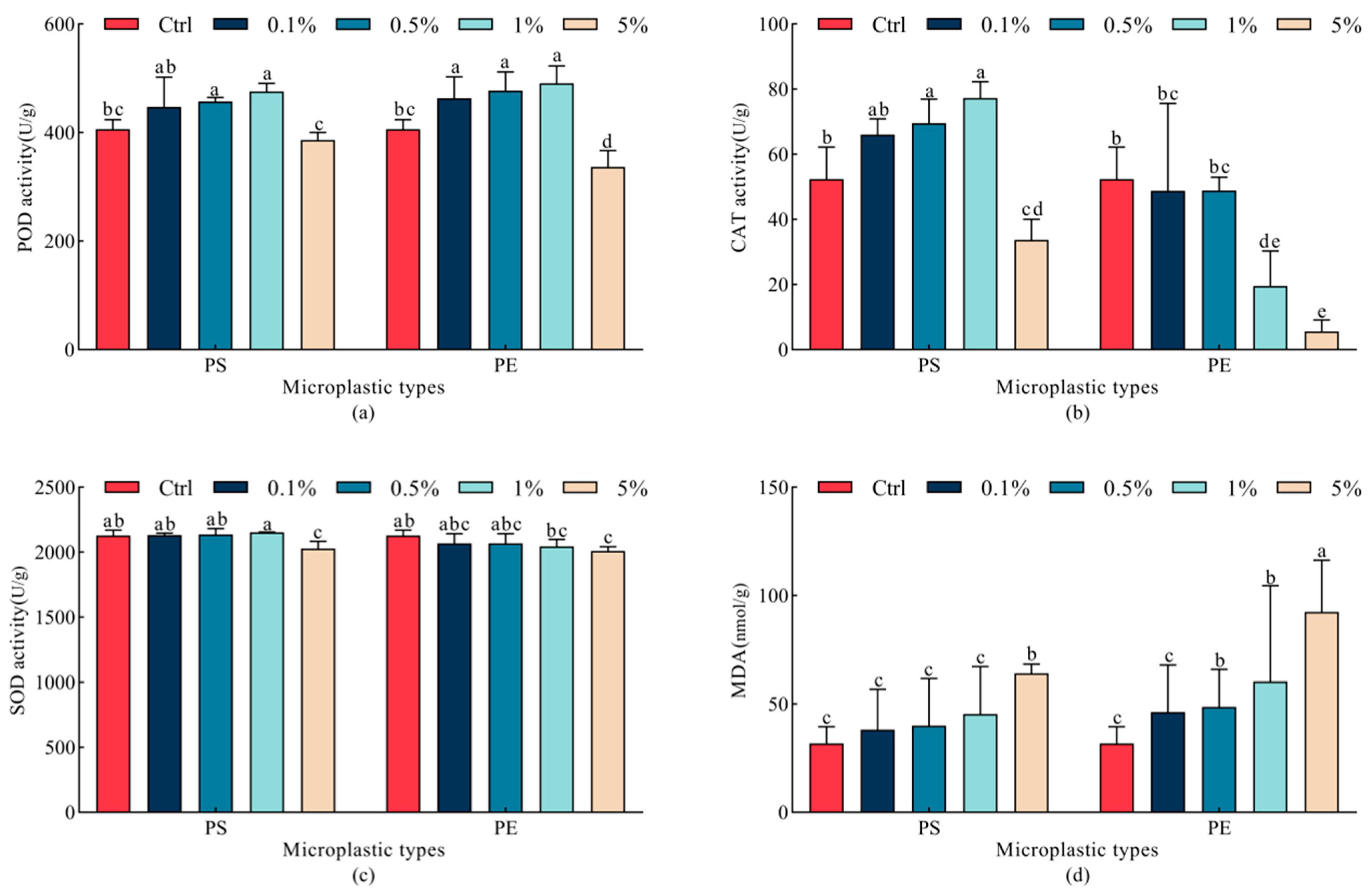

2.5. Effects of Microplastics on Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Oats

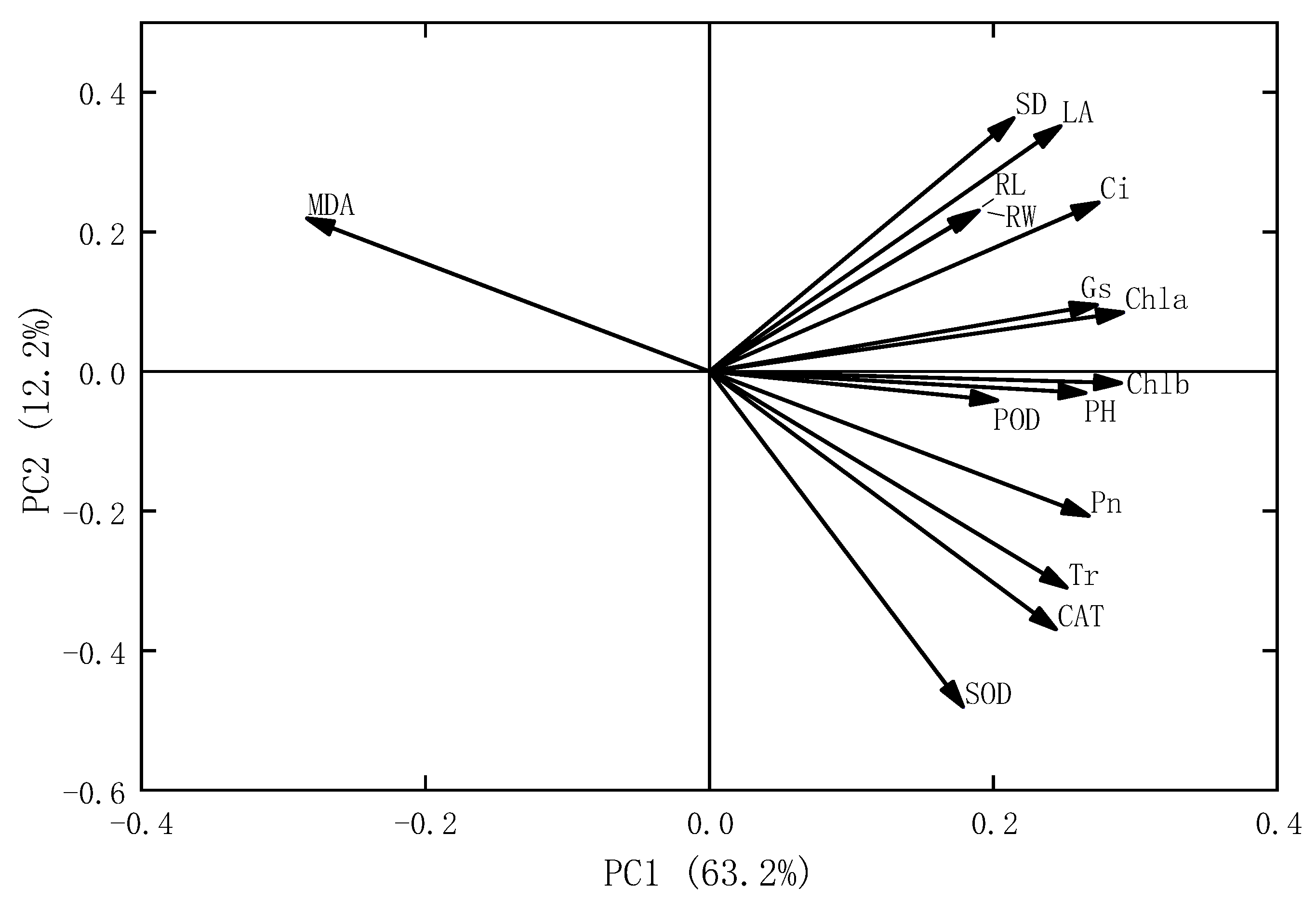

2.6. Interaction Effects of Microplastic Types and Concentrations on Oats

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Materials

4.2. Experimental Methods

4.2.1. Determination of Morphological Indicators in Oats

4.2.2. Determination of Chlorophyll Content in Oats

4.2.3. Measurement of Gas Exchange Parameters and Photosynthetic Rates in Oats

4.2.4. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity in Oats

4.2.5. Assessment of Membrane Peroxidation in Oats

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson, R.C. Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Sources, Consequences and Solutions. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Bergmann, M., Gutow, L., Klages, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, T.S.; Cole, M.; Lewis, C. Interactions of microplastic debris throughout the marine ecosystem. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.K.; Weng, Y.Z.; Gong, D.Q.; Bai, X. Physiological toxicity and antioxidant mechanism of photoaging microplastics on Pisum sativum L. seedlings. Toxics 2023, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.H.; Liu, W.T.; Shi, R.Y.; Zeb, A.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.T.; Zheng, Z.Q.; Tang, J.C. Effects of polyethylene and polylactic acid microplastics on plant growth and bacterial community in the soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 435, 129057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Yang, L.; Xu, L.; Yang, J. Soil microplastic pollution under different land uses in tropics, southwestern China. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.S.; Liu, Y.F. The distribution of microplastics in soil aggregate fractions in southwestern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhevagi, P.; Keerthi Sahasa, R.G.; Poornima, R.; Ramya, A. Unveiling the effect of microplastics on agricultural crops—A review. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2024, 26, 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hou, H.J.; Liu, Y.; Yin, S.S.; Bian, S.J.; Liang, S.; Wan, C.F.; Yuan, S.S.; Xiao, K.K.; Liu, B.C.; et al. Microplastics affect rice (Oryza sativa L.) quality by interfering metabolite accumulation and energy expenditure pathways: A field study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 422, 126834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Leng, Y.F.; Liu, X.N.; Wang, J. Microplastic pollution in vegetable farmlands of suburb Wuhan, central China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Wu, D.; Liu, P.; Hu, W.Y.; Xu, L.; Sun, Y.C.; Wu, Q.M.; Tian, K.; Huang, B.; Yoon, S.J.; et al. Occurrence, distribution and affecting factors of microplastics in agricultural soils along the lower reaches of Yangtze River, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.H.; Li, Y.; Qin, L.W.; Chen, X.D.; Ao, T.Y.; Liang, X.S.; Jin, K.B.; Dou, Y.Y.; Li, J.X.; Duan, X.J. Distribution and risk assessment of microplastics in a source water reservoir, Central China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.K.; Zhang, S.L.; Xing, H.; Yan, S.H.; Niu, X.G.; Wang, J.Q.; Fu, Q.; Aurangzeib, M. Spatial distribution of microplastics in Mollisols of the farmland in Northeast China: The role of field management and plastic sources. Geoderma 2025, 459, 117367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Shao, J.L.; Peng, C.X.; Gong, J.S. Novel insights related to soil microplastic abundance and vegetable microplastic contamination. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 484, 136727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Cui, Q.L.; Chen, L.; Zhu, X.Z.; Zhao, S.L.; Duan, C.J.; Zhang, X.C.; Song, D.X.; Fang, L.C. A critical review of microplastics in the soil-plant system: Distribution, uptake, phytotoxicity and prevention. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.Z.; Cassaro, R.; Ogura, A.P.; Vianna, M.M.G.R. A systematic review of the effects of microplastics and nanoplastics on the soil-plant system. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.X.; Liu, L. Short-term effects of polyethene and polypropylene microplastics on soil phosphorus and nitrogen availability. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.Y.; Liu, W.T.; Lian, Y.H.; Wang, Q.; Zeb, A.; Tang, J.C. Phytotoxicity of polystyrene, polyethylene and polypropylene microplastics on tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.). J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizzetto, L.; Futter, M.; Langaas, S. Are agricultural soils dumps for microplastics of urban origin? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 10777–10779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.L.; Huerta Lwanga, E.; Eldridge, S.M.; Johnston, P.; Hu, H.W.; Geissen, V.; Chen, D.L. An overview of microplastic and nanoplastic pollution in agroecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 1377–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.J.; Tu, C.; Li, L.Z.; Wang, X.Y.; Yang, J.; Feng, Y.D.; Zhu, X.; Fan, Q.H.; Luo, Y.M. Visual tracking of label-free microplastics in wheat seedlings and their effects on crop growth and physiology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 456, 131675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.D.; Wang, Z.S.; Shi, G.Y.; Gao, Y.B.; Zhang, H.; Liu, K.C. Effects of microplastics and salt single or combined stresses on growth and physiological responses of maize seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.G.; Zhao, M.S.; Meng, F.S.; Xiao, Y.L.; Dai, W.; Luan, Y.N. Effect of polystyrene microplastics on rice seed germination and antioxidant enzyme activity. Toxics 2021, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Luo, Y.M. Uptake of Microplastics and Their Effects on Plants. In Microplastics in Terrestrial Environments: Emerging Contaminants and Major Challenges; He, D., Luo, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.F.; Lei, C.L.; Xu, J.H.; Li, R.L. Foliar uptake and leaf-to-root translocation of nanoplastics with different coating charge in maize plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Wang, J.W.; Zhu, J.H.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.Q.; Zhan, X.H. The joint toxicity of polyethylene microplastic and phenanthrene to wheat seedlings. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 130967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.L.; Yang, X.M.; Pelaez, A.M.; Huerta Lwanga, E.; Beriot, N.; Gertsen, H.; Garbeva, P.; Geissen, V. Macro- and micro- plastics in soil-plant system: Effects of plastic mulch film residues on wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Luo, Z.X.; Lai, J.L.; Li, C.; Luo, X.G. Effects of polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs) on the physiology and molecular metabolism of corn (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.C.; Fu, Y.Y.; Guan, M.Z.; Yang, X.; Hu, M.G.; Cui, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.Q. The varied effects of different microplastics on stem development and carbon-nitrogen metabolism in tomato. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 376, 126387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gong, K.L.; Shao, X.C.; Liang, W.Y.; Zhang, W.; Peng, C. Effect of polyethylene, polyamide, and polylactic acid microplastics on Cr accumulation and toxicity to cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) in hydroponics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 450, 131022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiang, L.L.; Wang, F.; Redmile-Gordon, M.; Bian, Y.R.; Wang, Z.Q.; Gu, C.G.; Jiang, X.; Schäffer, A.; Xing, B.S. Transcriptomic and metabolomic changes in lettuce triggered by microplastics-stress. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 320, 121081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.M.; Jho, E.H. Effect of different types and shapes of microplastics on the growth of lettuce. Chemosphere 2023, 339, 139660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasane, P.; Jha, A.; Sabikhi, L.; Kumar, A.; Unnikrishnan, V.S. Nutritional advantages of oats and opportunities for its processing as value added foods—A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isari, E.A.; Papaioannou, D.; Kalavrouziotis, I.K.; Karapanagioti, H.K. Microplastics in agricultural soils: A case study in cultivation of watermelons and canning tomatoes. Water 2021, 13, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, J.D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.Y.; Tao, S.; Liu, W.X. Distribution characteristics of microplastics in agricultural soils from the largest vegetable production base in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.K.; Zhou, Y.F.; Liu, X.N.; Wang, J. New Perspective on the nanoplastics disrupting the reproduction of an endangered fern in artificial freshwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12715–12724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, J.P.; Fang, H.Y.; Xia, J.W.; Huang, G.M.; Huang, R.Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, L.Q.; Zhang, L.C.; Yuan, J.H. High concentrations of polyethylene microplastics restrain the growth of cinnamomum camphora seedling by reducing soil water holding capacity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbina, M.A.; Correa, F.; Aburto, F.; Ferrio, J.P. Adsorption of polyethylene microbeads and physiological effects on hydroponic maize. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, M.C. Plant cell walls: Supramolecular assemblies. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.R. Chlorophyll fluorescence: A probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R.; Chen, Y.F.; Li, P.Y.; Huang, H.F.; Xue, K.X.; Cai, S.Y.; Liao, X.L.; Jin, S.F.; Zheng, D.X. Microplastics in soil affect the growth and physiological characteristics of Chinese fir and Phoebe bournei seedlings. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 358, 124503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Li, R.J.; Li, Q.F.; Zhou, J.G.; Wang, G.Y. Physiological response of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) leaves to polystyrene nanoplastics pollution. Chemosphere 2020, 255, 127041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Singh Sidhu, G.P.; Bali, A.S.; Handa, N.; Kapoor, D.; Yadav, P.; Khanna, K.; et al. Photosynthetic response of plants under different abiotic stresses: A review. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Li, D.; Hui, K.L.; Wang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Fang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Xi, B.D.; Tan, W.B. The combined microplastics and heavy metals contamination between the soil and aquatic media: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Guo, P.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Xie, S.T.; Deng, J. Effect of microplastics exposure on the photosynthesis system of freshwater algae. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 374, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Qu, Q.; Lu, T.; Ke, M.J.; Zhu, Y.C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Du, B.B.; Pan, X.L.; Sun, L.W.; et al. The combined toxicity effect of nanoplastics and glyphosate on Microcystis aeruginosa growth. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.M.; Gao, M.L.; Song, Z.G.; Qiu, W.W. Microplastic particles increase arsenic toxicity to rice seedlings. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.M.; Song, Z.G.; Liu, Y.; Gao, M.L. Polystyrene particles combined with di-butyl phthalate cause significant decrease in photosynthesis and red lettuce quality. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 278, 116871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.H.; Yin, L.Y.; Guo, Y.B.; Han, T.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Liu, G.C.; Maqbool, F.; Xu, L.N.; Zhao, J. Insight into the absorption and migration of polystyrene nanoplastics in Eichhornia crassipes and related photosynthetic responses. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.P.; Liu, W.T.; Meng, L.Z.; Wu, J.N.; Chao, L.; Zeb, A.; Sun, Y.B. Foliar-applied polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs) reduce the growth and nutritional quality of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Environ. Pollut. 2021, 280, 116978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Ren, W.T.; Dai, Y.H.; Liu, L.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yu, X.Y.; Zhang, J.Z.; Wang, X.K.; Xing, B.S. Uptake, Distribution, and Transformation of CuO NPs in a Floating Plant Eichhornia crassipes and Related Stomatal Responses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 7686–7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.X.; Zhou, Y.C.; Gong, J.F. Physiological mechanisms of the tolerance response to manganese stress exhibited by Pinus massoniana, a candidate plant for the phytoremediation of Mn-contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 45422–45433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, S.A.M.; Duckett, J.G.; Sussmilch, F.C.; Pressel, S.; Renzaglia, K.S.; Hedrich, R.; Brodribb, T.J.; Merced, A. Stomata: The holey grail of plant evolution. Am. J. Bot. 2021, 108, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Panda, P.; Sahoo, L.; Panda, S.K. Reactive oxygen species signaling in plants under abiotic stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e23681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.F.; Chen, H.; Liao, Y.C.; Ye, Z.Q.; Li, M.; Klobučar, G. Ecotoxicity and genotoxicity of polystyrene microplastics on higher plant Vicia faba. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnocka, W.; Karpiński, S. Friend or foe? Reactive oxygen species production, scavenging and signaling in plant response to environmental stresses. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 122, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.F.; Chen, M.Y.; Lin, H.T.; Hung, Y.C.; Lin, Y.X.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, H.; Shi, J. DNP and ATP induced alteration in disease development of Phomopsis longanae Chi-inoculated longan fruit by acting on energy status and reactive oxygen species production-scavenging system. Food Chem. 2017, 228, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.Z.; Lin, H.T.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.F.; Wang, H.; Lin, M.S.; Hung, Y.C.; Chen, Y.H. The roles of ROS production-scavenging system in Lasiodiplodia theobromae (Pat.) Griff. & Maubl.-induced pericarp browning and disease development of harvested longan fruit. Food Chem. 2018, 247, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Guha, T.; Barman, F.; Natarajan, L.; Kundu, R.; Mukherjee, A.; Paul, S. Surface functionalization and size of polystyrene microplastics concomitantly regulate growth, photosynthesis and anti-oxidant status of Cicer arietinum L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 194, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, B.; Russell, C.W.; Green, D.S. Effects of microplastics in soil ecosystems: Above and below ground. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11496–11506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.L.; Li, Y.Z.; Liu, S.L.; Junaid, M.; Wang, J. Effects of micro(nano)plastics on higher plants and the rhizosphere environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.L.; Xu, Y.L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.L.; Wang, C.W.; Dong, Y.M.; Song, Z.G. Effect of polystyrene on di-butyl phthalate (DBP) bioavailability and DBP-induced phytotoxicity in lettuce. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekner-Grzyb, A.; Duka, A.; Grzyb, T.; Lopes, I.; Chmielowska-Bąk, J. Plants oxidative response to nanoplastic. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1027608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Balhara, R.; Hossain, Z.; Singh, K. Mechanistic insights into polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs) mediated imbalance of redox homeostasis and disruption of antioxidant defense system leading to oxidative stress in black mustard (Brassica nigra L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229, 110480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, N.; Wang, T.F.; Gan, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Plant flavonoids: Classification, distribution, biosynthesis, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.F.; Shi, Z.H.; Shan, X.L.; Yang, S.P.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Guo, X.T. Insights into growth-affecting effect of nanomaterials: Using metabolomics and transcriptomics to reveal the molecular mechanisms of cucumber leaves upon exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Du, X.Y.; Zhou, R.R.; Lian, J.P.; Guo, X.R.; Tang, Z.H. Effect of cadmium and polystyrene nanoplastics on the growth, antioxidant content, ionome, and metabolism of dandelion seedlings. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 354, 124188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.H.; Li, Y.J.; Lin, X.L.; Yu, Y. Effects and mechanisms of polystyrene micro- and nano-plastics on the spread of antibiotic resistance genes from soil to lettuce. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.C.; Cui, Y.L.; Cheng, L.; Hu, M.G.; Guan, M.Z.; Fu, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.Q. Exposure to polyethylene terephthalate microplastics induces reprogramming of flavonoids metabolism and gene regulatory networks in Capsicum annuum. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 293, 118022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J.K. Thriving under stress: How plants balance growth and the stress response. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Sun, J.F.; Shabbir, S.; Khattak, W.A.; Ren, G.Q.; Nie, X.J.; Bo, Y.W.; Javed, Q.; Du, D.L.; Sonne, C. A review of plants strategies to resist biotic and abiotic environmental stressors. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Zhao, X.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Han, J.Q. The abundance, characteristics and distribution of microplastics (MPs) in farmland soil-based on research in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 876, 162782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.K.; Zhang, S.L.; Wang, J.Q.; Wang, W.; Xu, B.; Hao, X.H.; Aurangzeib, M. Field management changes the distribution of mesoplastic and macroplastic in Mollisols of Northeast China. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Z.; Dou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, K.Z.; Li, Y.X. Distribution characteristics of soil microplastics and their impact on soil physicochemical properties in agricultural areas of the North China plain. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2024, 26, 1556–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.A.; Lau, C.W.; Till, J.; Kloas, W.; Lehmann, A.; Becker, R.; Rillig, M.C. Impacts of microplastics on the soil biophysical environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9656–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, M. Microplastic contamination: A rising environmental crisis with potential oncogenic implications. Cureus 2025, 17, e85191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y.; Zhang, X.Q.; Zhang, S.Q.; Zhang, S.W.; Sun, Y.H. Interactions of microplastics and cadmium on plant growth and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in an agricultural soil. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicator | Parameter | Mps Type | Mps Concentration | Type × Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significance Level (p) | ||||

| Growth indicators | PH | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.002 ** |

| RL | 0.401 | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | |

| RFW | 0.898 | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | |

| SD | 0.076 | 0.000 ** | 0.003 ** | |

| LA | 0.029 * | 0.000 ** | 0.010 * | |

| Chlorophyll content | Chla | 0.001 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** |

| Chlb | 0.009 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.004 ** | |

| Chl | 0.001 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | |

| Gas exchange parameters | Pn | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.011 * |

| Gs | 0.035 * | 0.000 ** | 0.594 | |

| Ci | 0.937 | 0.000 ** | 0.010 * | |

| Tr | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.055 | |

| Antioxidant enzyme | POD | 0.976 | 0.000 ** | 0.139 |

| SOD | 0.009 ** | 0.011 * | 0.356 | |

| CAT | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | |

| MDA | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.015 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Tan, S.; Mao, P.; Wang, Q.; Ma, W. Effects of Polyethylene and Polystyrene Microplastics on Oat (Avena sativa L.) Growth and Physiological Characteristics. Plants 2026, 15, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010056

Yang Z, Zhao L, Tan S, Mao P, Wang Q, Ma W. Effects of Polyethylene and Polystyrene Microplastics on Oat (Avena sativa L.) Growth and Physiological Characteristics. Plants. 2026; 15(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Zhibo, Lingping Zhao, Shitu Tan, Pei Mao, Qunying Wang, and Wenfeng Ma. 2026. "Effects of Polyethylene and Polystyrene Microplastics on Oat (Avena sativa L.) Growth and Physiological Characteristics" Plants 15, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010056

APA StyleYang, Z., Zhao, L., Tan, S., Mao, P., Wang, Q., & Ma, W. (2026). Effects of Polyethylene and Polystyrene Microplastics on Oat (Avena sativa L.) Growth and Physiological Characteristics. Plants, 15(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010056