Genetic Variability of Gene Expression in Tomato Fruits Ripened on and off the Vine: Cis-Regulatory Elements Associated with Differential Transcription Patterns in the Most Discrepant Variety

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

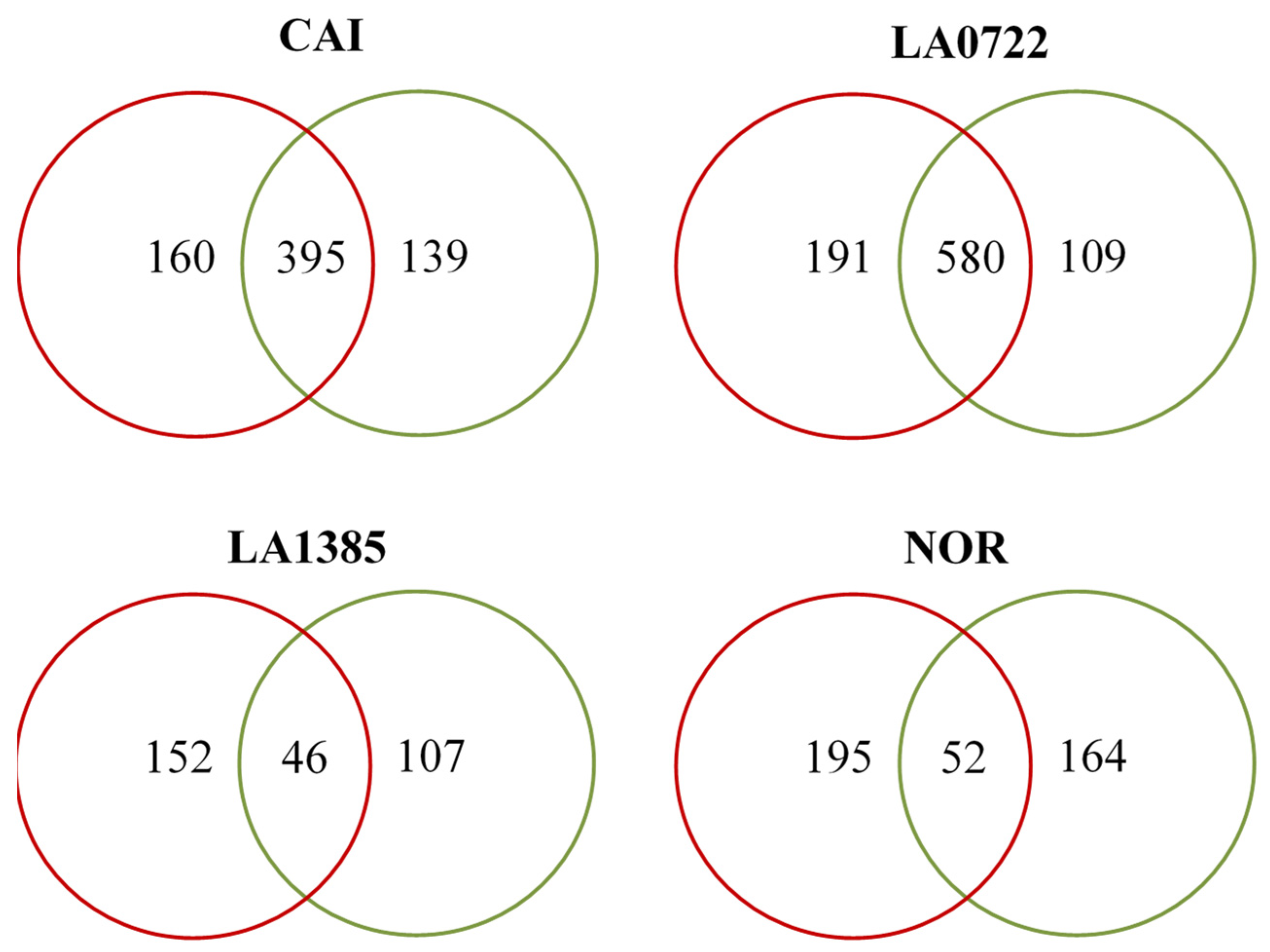

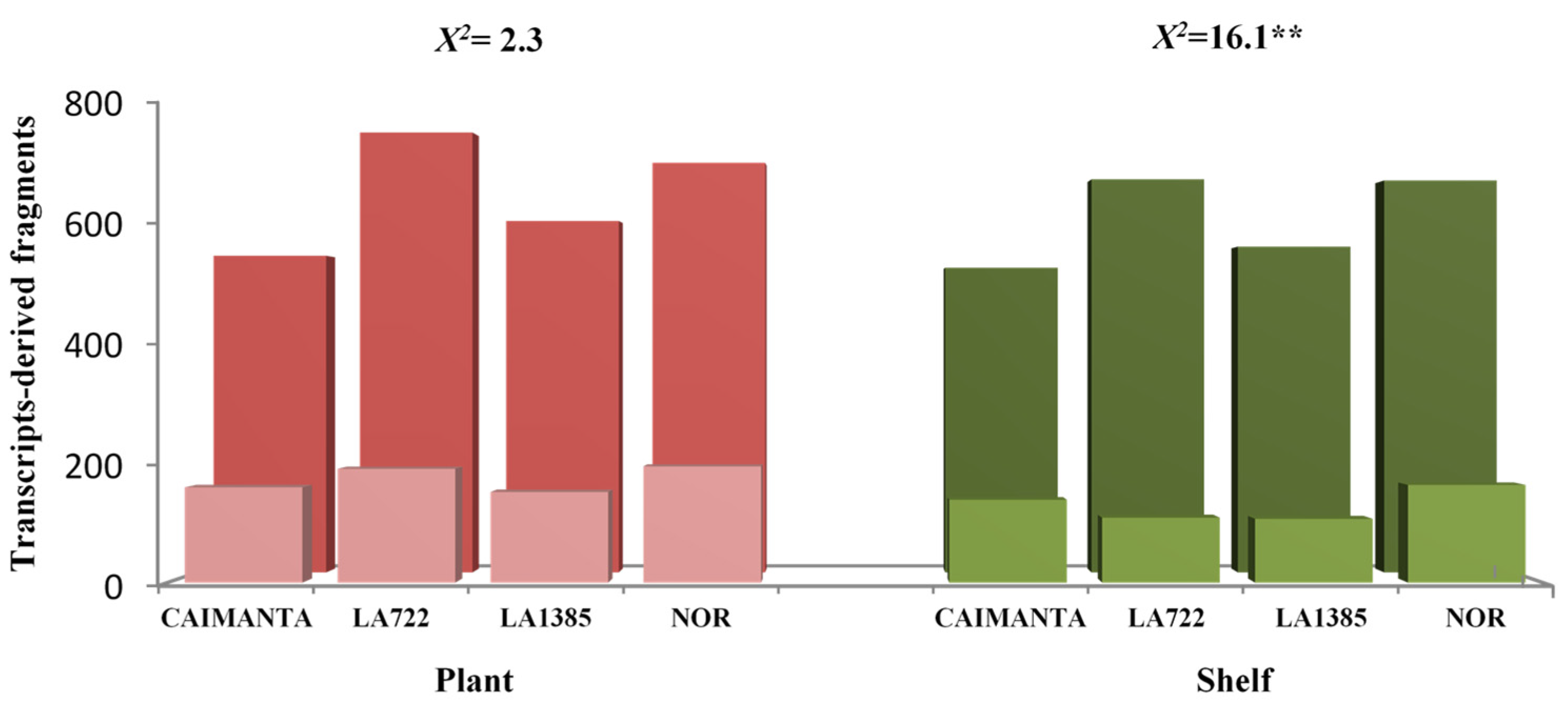

2.1. Analysis of cDNA-AFLP Expression Profiles of Plant-Ripened and Shelf-Ripened Fruits

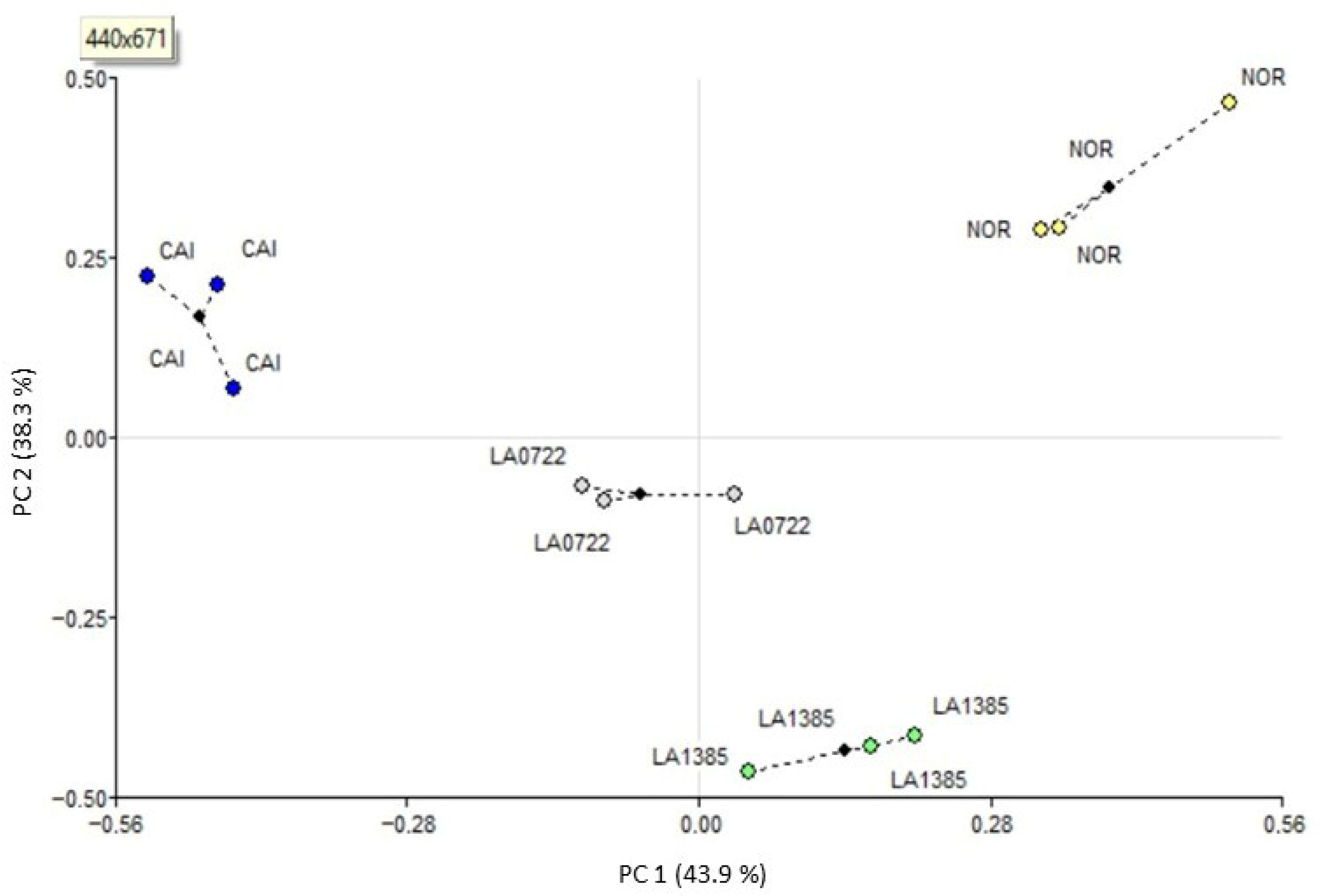

2.2. Association Analysis by Generalized Procrustes Among cDNA-AFLP Expression Profiles and Traits Related to Fruit Ripening and Identification of the Most Discrepant Genotype

2.3. Sequence and In Silico Analysis in CAI and NOR Genotypes

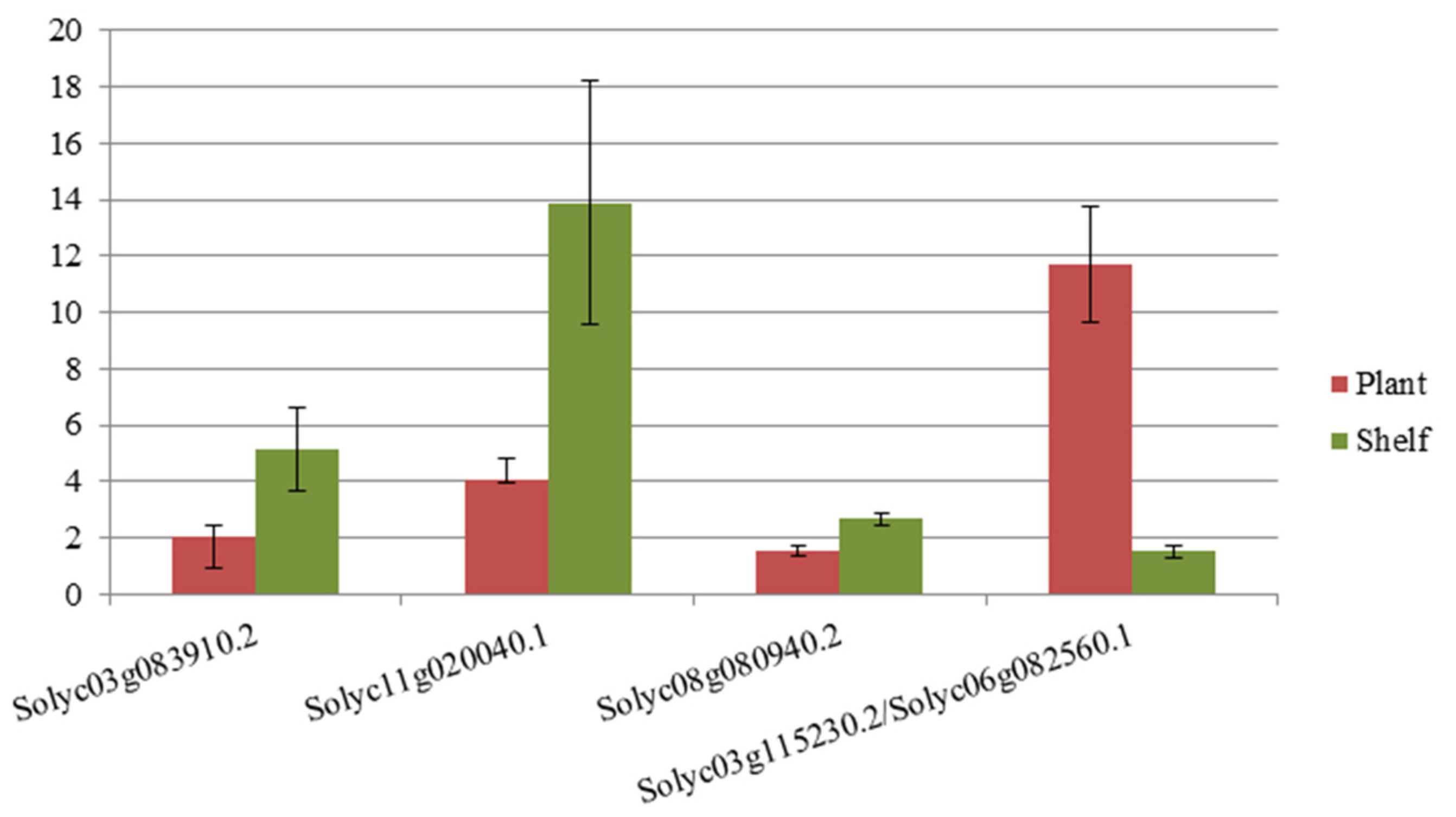

Identification and Validation of Differentially Expressed Gene from Transcript-Derived Fragments

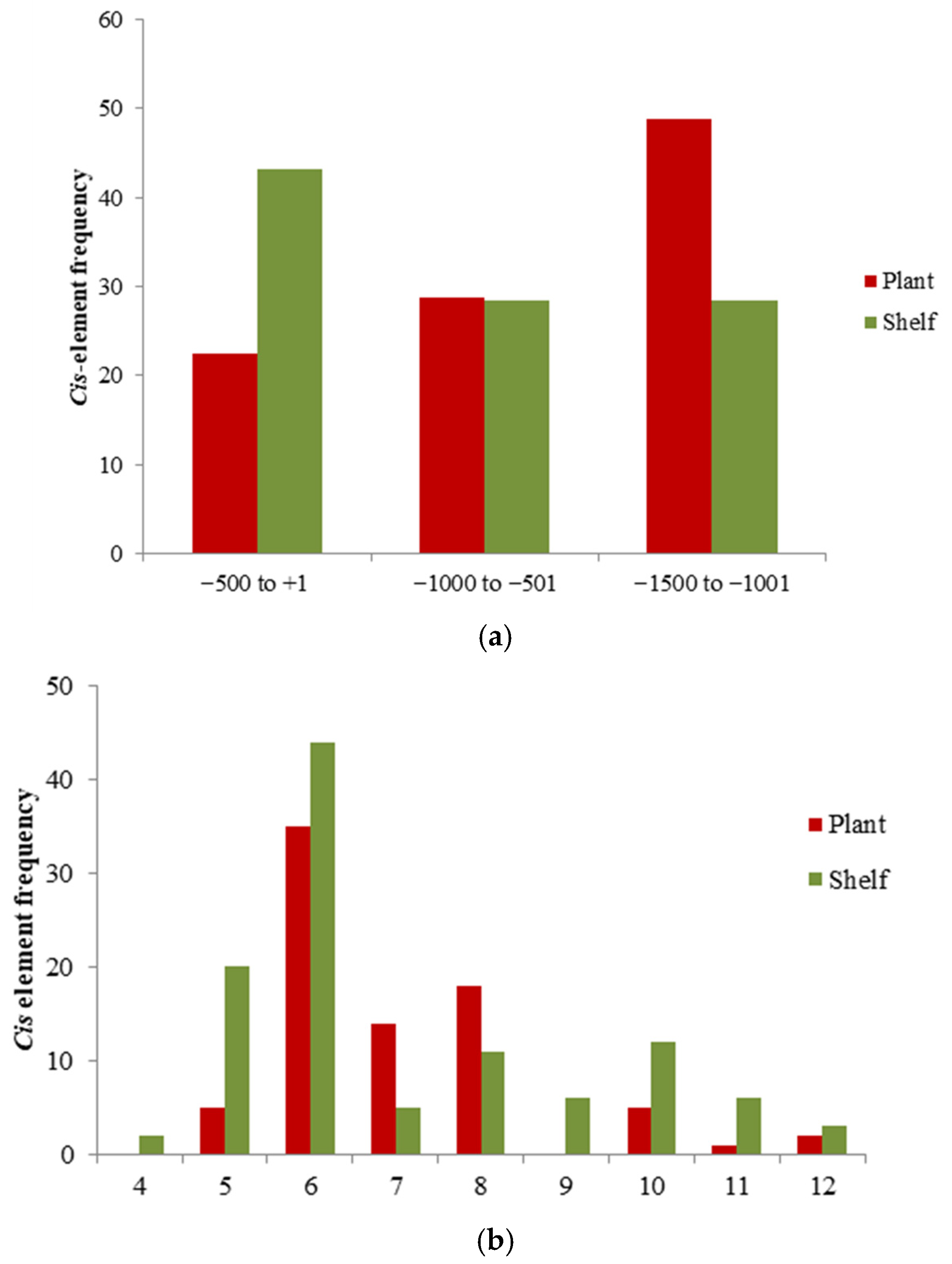

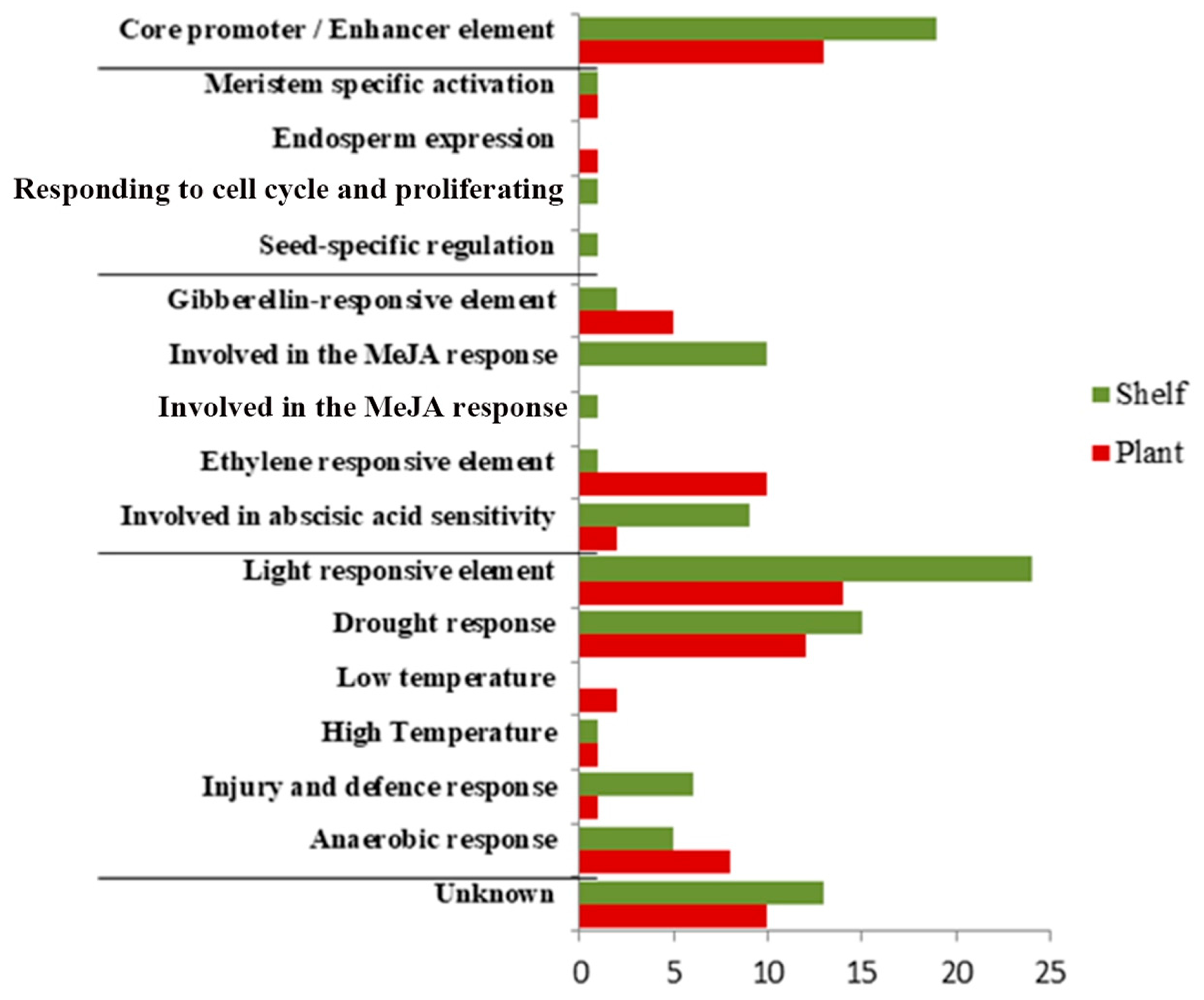

2.4. Identification of Promoter Regions and Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements

3. Discussion

3.1. Analysis of cDNA-AFLP Expression Profiles of Plant-Ripened and Shelf-Ripened Fruits

3.2. Associations Among Molecular and Phenotypic Variability

3.3. Identification and Validation of Differentially Expressed Gene-From Transcript Derived Fragments

3.4. Identification of Promoter Regions and Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Evaluation of Gene Expression by cDNA-AFLP

4.1.1. Plant Material

4.1.2. cDNA Synthesis and Obtaining of cDNA-AFLP Profiles

4.2. Association of cDNA-AFLP Amplicons at Both Ripening Conditions and Quantitative Traits and Identification of the Most Discrepant Genotypes

4.3. Analysis of Is-Regulatory Elements in the Most Discrepant Genotypes

4.3.1. Validation of cDNA-AFLP Amplicons by Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR

4.3.2. Promoter Sequence Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duret, S.; Aubert, C.; Annibal, S.; Derens-Bertheau, E.; Cottet, V.; Jost, M.; Chalot, G.; Flick, D.; Moureh, J.; Laguerre, O.; et al. Impact of harvest maturity and storage conditions on tomato quality: A comprehensive experimental and modeling study. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 219, 113286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanonni, J.J. Genetic regulation of fruit development and ripening. Plant Cell 2004, 6, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adaskaveg, J.A.; Silva, C.J.; Huang, P.; Blanco-Ulate, B. Single and double mutations in tomato ripening transcription factors have distinct effects on fruit development and quality traits. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 647035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.R.; Pereira da Costa, J.H.; Tomat, D.D.; Pratta, G.R.; Zorzoli, R.; Picardi, L.A. Pericarp total protein profiles as molecular markers of tomato fruit quality traits in two segregating populations. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 130, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giacomo, M.; Luciani, M.D.; Cambiaso, V.; Zozoli, R.; Rodríguez, G.R.; Pereira da Costa, J.H. Tomato near isogenic lines to unravel the genetic diversity of S. pimpinellifolium LA0722 for fruit quality and shelf life breeding. Euphytica 2020, 216, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Yu, L.; Zhu, F.; Cao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Geng, X.; Mao, H.; Lv, L. Possible mechanism of the detached unripe green tomato fruit turning red. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 37, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Liu, S.T.; Wei, Y.P.; Zhou, D.Y.; Hou, X.L.; Li, Y.; Hu, C.M. cDNA-AFLP analysis reveals differential gene expression in incompatible interaction between infected non-heading Chinese cabbage and Hyaloperonospora parasitica. Hortic. Res. 2016, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira da Costa, J.H.; Rodríguez, G.R.; Picardi, L.A.; Zorxoli, R.; Pratta, G.R. Genome-wide expression analysis at three fruit ripening stages for tomato genotypes differing in fruit shelf life. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 229, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; An, J.; Deng, W.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z. Metabolic and transcriptional regulatory mechanism associated with postharvest fruit and senescence in cherry tomatoes. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 168, 111274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacchiarelli, P.; Spetale, F.E.; Arce, D.P.; Tapia, E.; Pratta, G.R. Transcriptomics of fruit ripening in a tomato wide cross and genetic analysis of differential expressed genes among parent and hybrids. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 330, 113037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigal, A.; Siamsa, M.; Doyle, S.M.; Ritter, A.; Raggi, S.; Vain, T.; O′Brien, J.A.; Goossens, A.; Pauwels, L.; Robert, S. A network of stress-related genes regulates hypocotyl elongation downstream of selective auxin perception. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Garcia, C.M.; Finer, J.J. Identification and validation of promoters and cis-acting regulatory elements. Plant Sci. 2014, 217, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ge, P.; Chen, L.; Ahiakpa, J.K.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, Y. Ethylene response factors ERF.B2 and ERF.B5 synergically regulate ascorbic acid biosynthesis at multiple sites in tomato. Plant J. 2025, 123, E70479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, J.C. Generalized procrustes analysis. Psychometrika 1975, 40, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stölting, K.N.; Gort, G.; Wüst, C.; Wilson, A.B. Eukaryotic transcriptomics in silico: Optimizing cDNA-AFLP efficiency. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratta, G.R.; Rodríguez, G.R.; Zorzoli, R. Molecular markers detect stable genomic regions underlying tomato fruit shelf life and weight. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2011, 11, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzoli, R.; Picardi, L.A.; Pratta, G. Efecto de los mutantes nor y rin y de genes de origen silvestres sobre la calidad postcosecha de los frutos de tomate. Mendeliana 1998, 13, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Angenent, G.C.; Seymour, G.; De Maagd, R.A. Revisiting the role of master regulators in tomato ripening. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawamura, M.; Knegt, E.; Bruinsma, J. Levels of endogenous ethylene, carbon dioxide, and soluble pectin, and activities of pectin methylesterase and polygalacturonase in ripening tomato fruits. Plant Cell Physiol. 1978, 19, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Pirrello, J.; Chervin, C.; Roustan, J.P.; Bouzayen, M. Ethylene control of fruit ripening: Revisiting the complex network of transcriptional regulation. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 2380–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wei, W.; Fan, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zhu, H.; Shan, W.; Chen, J.; et al. Re-evaluation of the nor mutation and the role of the NAC-NOR transcription factor in tomato fruit ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 3560–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhu, N.; Wu, M.; Cai-Zhong, D.; Grierson, D.; Luo, Y.; Shen, W.; Zhong, S.; Fu, D.Q.; Qu, G. Diversity and redundancy of the ripening regulatory networks revealed by the fruit ENCODE and the new CRISPR/Cas9 CNR and NOR mutants. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Medico, A.P.; Cabodevila, V.G.; Vitelleschi, M.S.; Pratta, G.R. Characterization of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) generations according to three-way data analysis. Bragantia 2020, 79, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabodevila, V.G.; Picardi, L.A.; Pratta, G.R. A multivariate aproach to explore the genetic variability in the F2 segregating population of a tomato second cycle hybrid. Basic Appl. Genet. 2017, 28, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mahuad, S.L.; Pratta, G.R.; Rodríguez, G.R.; Zorzoli, R.; Picardi, L.A. Preservation of Solanum pimpinellifolium genomic fragments recombinant genotypes improved the fruit quality of tomato. J. Genet. 2013, 92, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, T.P.; Alba, R. The tomato genome fleshed out. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Seymour, G.B. Molecular and biochemical basis of softening in tomato. Mol. Hortic. 2022, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibraheem, O.; Botha, C.E.J.; Bradley, G. In silico analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements in 5′ regulatory regions of sucrose transporter gene families in rice (Oryza sativa Japonica) and Arabidopsis thaliana. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2010, 34, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Cao, Q.; Li, Y.; He, M.; Liu, X. Advances in cis-element and natural variation-mediated transcriptional regulation and applications in gene editing of mayor crops. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 5441–5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, S.; Hossain Bhuiyan, F.; Akther, J.; Prodhan, S.H.; Hoque, H. The dymanics of cis-regulatory elements in promoter regions of tomato sucrose transporter genes. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2020, 7, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Pati, P.K. Analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements of Respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rboh) gene families in Arabidopsis and rice provides clues for their diverse functions. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2016, 62, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basehoar, A.D.; Zanton, S.J.; Pugh, B.F. Identification and distinct regulation of yeast TATA box-containing genes. Cell 2004, 116, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmuradov, I.A.; Umarov, R.K.; Solovyev, V.V. TSSPlant: A new tool for prediction of plant Pol II promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Zhou, W. Frequency distribution of TATA Box and extension sequences on human promoters. In First International Multi-Symposiums on Computer and Computational Sciences (IMSCCS’06); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, K.; Haslbeck, M.; Buchner, J. The Heat Shock Response: Life on the Verge of Death. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faurobert, M.; Mihr, C.; Bertin, N.; Pawlowski, T.; Negroni, L.; Sommerer, N.; Causse, M. Major proteome variations associated with cherry tomato pericarp development and ripening. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1327–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasinos, C. Tight regulation of expression of two Arabidopsis cytosolic Hsp90 genes during embryo development. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Guo, M.; Liu, T. Unraveling the target genes of RIN transcription factor during tomato fruit ripening and softening. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Lee, K.; Hoshikawa, K.; Kang, M.; Jang, S. Molecular bases of heat stress responses in vegetable crops with focusing on heat shock factors and heat shock proteins. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 837152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkindale, J.; Vierling, E. Core genome responses involved in acclimation to high temperature. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, F.Z.; Chapeaurouge, A.; Perales, J.; Bertolini, M.C. A systematic approach to identify STRE-binding proteins of the gsn glycogen synthase gene promoter in Neurospora crassa. Proteomics 2008, 8, 2052–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graci, S.; Ruggieri, V.; Francesca, S.; Rigano, M.M.; Barone, A. Genomic Insights into the Origin of a Thermotolerant Tomato Line and Identification of Candidate Genes for Heat Stress. Genes 2023, 14, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, D.; Spetale, F.; Krsticevic, F.; Cacchiarelli, P.; De Las Rivas, J.; Ponce, S.; Pratta, G.; Tapia, E. Regulatory motifs found in the small heat shock protein (sHSP) gene family in tomato. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, K.; Grierson, D. Molecular and hormonal mechanisms regulating fleshy fruit ripening. Cells 2021, 10, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, P. Computational approaches for deciphering the transcriptional regulatory network by promoter analysis. Biosilico 2003, 1, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.R.; Pratta, G.R.; Liberatti, D.R.; Zorzoli, R.; Picardi, L.A. Inheritance of shelf life and other quality traits of tomato fruit estimated from F1′s, F2′s and backcross generations derived from standard cultivar, nor homozygote and wild cherry tomato. Euphytica 2010, 176, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuylsteke, M.; Peleman, J.D.; Van Eijk, M.J.T. AFLP-based transcript profiling (cDNA-AFLP) for genome-wide expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1399–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito-Rodríguez, M.; Borge, A.A.; Borges-Pérez, A.; Pérez, J.A. Selection of internal control genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies during tomato development process. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BIOEDIT: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/ NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van der Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Identifier/Gene | Cr. | C. | Location Gene/Length (bp) | Function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Solyc03g083910.2 | 3 | - | 53851092..5855368/4277 | β-fructofuranosidase acid. Involved in the sucrose metabolism pathway, which is part of glycan biosynthesis. | M |

| 2 | Solyc12g044820.1 | 12 | + | 37714905-37720440/5536 | ABC transporter, member of the C 8 family, ATPase-coupled transmembrane transporter activity. | T |

| 3 | Solyc11g020040.1 | 11 | + | 10015582..10019521/3940 | Heat shock protein 70 (HSP70). Unfolded protein binding. | S |

| 4 | Solyc08g080940.2 | 8 | + | 64084698..64087731/3034 | Glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx). Protects cells and enzymes from oxidative damage by catalyzing the reduction of hydrogen peroxide, lipid peroxides, and organic hydroperoxide by glutathione. | S |

| 5 | Solyc06g076940.2 | 6 | + | 47818952..47822936/3985 | NudC-domain proteins. Unfolded protein binding. | CS |

| 6 | Solyc11g020040.2 | 11 | + | 10015582..10019521/3940 | Heat shock protein (HSP70). Unfolded protein binding. | S |

| 7 | Solyc03g115230.2 | 3 | - | 65011966..65016121/4156 | ClpB/ATPsa chaperone protein. ATP binding. ATPase associated with various cellular activities. | S |

| 8 | Solyc06g082560.1 | 6 | + | 48340001..48342565/2565 | ClpB/ATPsa chaperone protein. ATP binding. ATPase associated with various cellular activities. | S |

| 9 | Solyc03g112910.2 | 3 | + | 63189344..63204073/14730 | Pantothenate kinase. Catalyzes the phosphorylation of pantothenate, the first step in CoA biosynthesis. It may play a role in the physiological regulation of intracellular CoA concentration. | CS |

| 10 | Solyc06g064630.2 | 6 | - | 40270353..40272844/2492 | Ribosomal protein L15 | CS |

| Identifier/Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | PCR In Silico |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solyc03g083910.2 | TACCTGTGTTGGACGGTGAA | TCGTGCTGCTCCATTTACTG | Solyc03g083910.2 |

| Solyc12g044820.1 | TTTCGCCTGGTAGAGCCTTA | GTTCGAACACTCCCCTTGAA | Solyc12g044820.1 |

| Solyc11g020040.1 | TACAAGGGCCAAGTTTGAGG | GAACAGCCGGTATTCGTGTT | Solyc11g020040.1 |

| Solyc08g080940.2 | ACCAGTTTGGTGGACAGGAG | AAGAACCCACCTTTGCTTGA | Solyc08g080940.2 |

| Solyc06g076940.2 | CCCAGTGAAGACCGATTGTT | GGAACCTTTGAAGCATGAGC | Solyc06g076940.2 |

| Solyc03g115230.2/Solyc06g082560.1 | ATACGGTGCCATCCAAGAAG | CATTCTGGCCAAGCCTAGAG | Solyc03g115230.2 |

| CTAGGCTTGGGCAGAATGAG | AGTTGGTTGTTGTGGCCTTC | Solyc06g082560.1 | |

| Solyc03g112910.2 | TAGGAGCAAGGTAGGCAGGA | GAATTGAACTCCCAGGCAAA | Solyc03g112910.2 |

| Solyc06g064630.2 | GAGGAAGAAGCAGTCGGATG | TGCCTTGTCAGGACGTGTAG | Solyc06g064630.2 |

| Treatment | Transcript ID/Length (bp) | 5′UTR Before ATG a | N° of Exons | Region CDS b | CDS Length (bp) | Protein Size (aa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shelf | Solyc03g083910.2.1/2299 | 1–82 | 7 | 83–4011 | 1947 | 649 |

| Solyc11g020040.1.1/2079 | 1–317 | 8 | 318–4258 | 2079 | 693 | |

| Solyc08g080940.2.1/1022 | 1–36 | 6 | 37–1059 | 720 | 240 | |

| Plant | Solyc03g115230.2.1/3194 | 1–24/527–633 c | 7 | 701–3831 | 2736 | 912 |

| Solyc06g082560.1.1/2565 | - | 1 | - | 2565 | 855 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pereira da Costa, J.H.; Souza Canada, E.D.; Ochogavía, A.C.; Rodríguez, G.R.; Pratta, G.R. Genetic Variability of Gene Expression in Tomato Fruits Ripened on and off the Vine: Cis-Regulatory Elements Associated with Differential Transcription Patterns in the Most Discrepant Variety. Plants 2026, 15, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010053

Pereira da Costa JH, Souza Canada ED, Ochogavía AC, Rodríguez GR, Pratta GR. Genetic Variability of Gene Expression in Tomato Fruits Ripened on and off the Vine: Cis-Regulatory Elements Associated with Differential Transcription Patterns in the Most Discrepant Variety. Plants. 2026; 15(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010053

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira da Costa, Javier Hernán, Eduardo Daniel Souza Canada, Ana Claudia Ochogavía, Gustavo Rubén Rodríguez, and Guillermo Raúl Pratta. 2026. "Genetic Variability of Gene Expression in Tomato Fruits Ripened on and off the Vine: Cis-Regulatory Elements Associated with Differential Transcription Patterns in the Most Discrepant Variety" Plants 15, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010053

APA StylePereira da Costa, J. H., Souza Canada, E. D., Ochogavía, A. C., Rodríguez, G. R., & Pratta, G. R. (2026). Genetic Variability of Gene Expression in Tomato Fruits Ripened on and off the Vine: Cis-Regulatory Elements Associated with Differential Transcription Patterns in the Most Discrepant Variety. Plants, 15(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010053