Time-Series Comparative Transcriptome Analyses of Two Potato Cultivars with Different Verticillium Wilt Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Two Potato Cultivars Showed Contrasting Resistance to Verticillium Wilt

2.2. Complexed Transcriptomic Changes Associated with VW Inoculation

2.2.1. VW-Responsive Genes in LS8 and SP

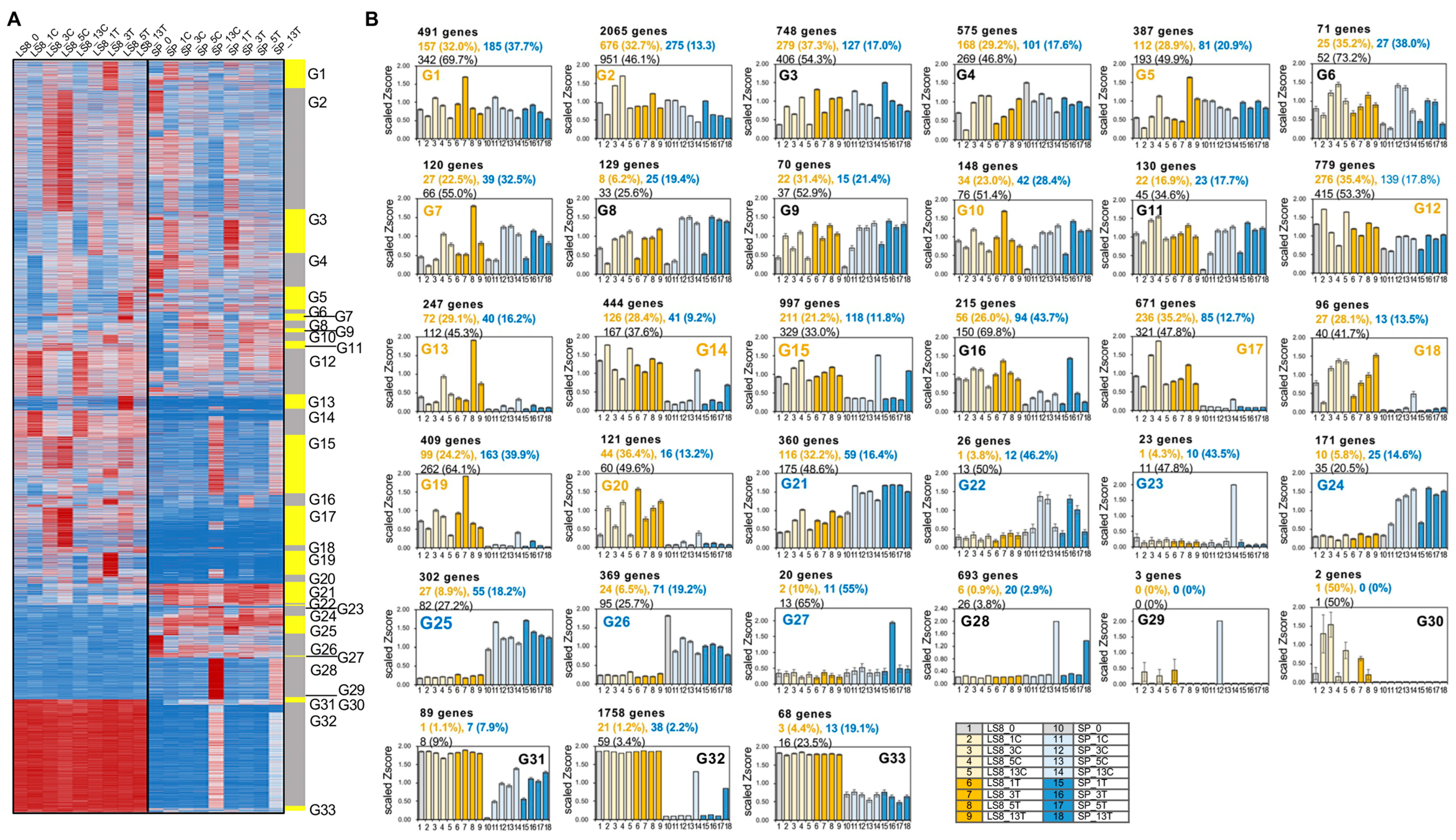

2.2.2. Identifying Genes Clusters with Distinct Expression Patterns Between LS8 and SP

2.3. Functions Associated with VW-Responsive Expression Groups Underline Cell Wall Metabolism Differences Between the Cultivars

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Materials and Experiment Design

3.2. Pathogen Infection Assay

3.3. RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

3.4. RNA-Seq Analyses

3.5. Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase (PAL)—Encoding Gene Identification and Phylogenetic Analyses

3.6. Analyses of PAL Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DEG | Differentially expressed gene |

| dpi | Day post inoculation |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped fragments |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association analysis |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| PAL | phenylalanine ammonia-lyase |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PCC | Pearson correlation coefficient |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| TWAS | Transcriptome-wide association analysis |

| VW | Verticillium wilt |

References

- Perez, W.; Alarcon, L.; Rojas, T.; Correa, Y.; Juarez, H.; Andrade-Piedra, J.L.; Anglin, N.L.; Elli, D. Screening South American Potato Landraces and Potato Wild Relatives for Novel Sources of Late Blight Resistance. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1845–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Fradin, E.F.; Thomma, B.P.H.J. Physiology and Molecular Aspects of Verticillium Wilt Diseases Caused by V. dahliae and V. alboatrum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 7, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.A.; Dung, J. Verticillium wilt of potato–the pathogen, disease and management. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 32, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.C.; Davis, J.R.; Powelson, M.L.; Rouse, D.I. Potato early dying: Causal agents and management strategies. Plant Dis. 1987, 71, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powelson, M.L.; Rowe, R.C. Biology and management of early dying of potatoes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1993, 31, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.C.; Powelson, M.L. Potato early dying: Management challenges in a changing production environment. Plant Dis. 2002, 86, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lu, X.; Wang, A.; Xue, C.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, J. The effects and interrelationships of intercropping on cotton Verticillium Wilt and soil microbial communities. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.R.; Huisman, O.C.; Everson, D.O.; Nolte, P.; Sorensen, L.H.; Schneider, A.T. Ecological relationships of Verticillium wilt suppression of potato by green manures. Am. J. Potato Res. 2010, 87, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, N.; Powelson, M.L.; Dick, R.P.; Crowe, F.J. Effects of green manure type and amendment rate on Verticillium wilt severity and yield of Russet Burbank potato. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simko, I.; Haynes, K.G.; Jones, R.W. Mining data from potato pedigrees: Tracking the origin of susceptibility and resistance to Verticillium dahliae in North American cultivars through molecular marker analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Li, C.; Li, G.; Wang, P.; Peng, Z.; Cheng, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, W.; et al. Genome architecture and tetrasomic inheritance of autotetraploid potato. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1211–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoopes, G.; Meng, X.; Hamilton, J.P.; Achakkagari, S.R.; Guesdes, F.A.F.; Bolger, M.E.; Coombs, J.J.; Esselink, D.; Kaiser, N.R.; Kodde, L.; et al. Phased, chromosome-scale genome assemblies of tetraploid potato reveal a complex genome, transcriptome, and predicted proteome landscape underpinning genetic diversity. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Jiao, W.; Krause, K.; Campoy, J.A.; Goel, M.; Folz-Donahue, K.; Kukat, C.; Huettel, B.; Schneeberger, K. Chromosome-scale and haplotype-resolved genome assembly of a tetraploid potato cultivar. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mari, R.S.; Schrinner, S.; Finkers, R.; Ziegler, F.M.R.; Arens, P.; Schmidt, M.H.W.; Usadel, B.; Klau, G.W.; Marschall, T. Haplotype-resolved assembly of a tetraploid potato genome using long reads and low-depth offspring data. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Tusso, S.; Dent, C.I.; Goel, M.; Wijfjes, R.Y.; Baus, L.C.; Dong, X.; Campoy, J.A.; Kurdadze, A.; Walkemeier, B.; et al. The phased pan-genome of tetraploid European potato. Nature 2025, 642, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Wu, P.; Xu, W.; Yang, D.; Ming, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wang, W.; Ma, J.; Nie, X.; et al. A panoramic view of cotton resistance to Verticillium dahliae: From genetic architectures to precision genomic selection. iMeta 2025, 4, e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Jiang, F.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhan, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Duan, H.; Ge, X.; et al. Verticillium dahliae effector Vd06254 disrupts cotton defense response by interfering with GhMYC3-GhCCD8-mediated hormonal crosstalk between jasmonic acid and strigolactones. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 2755–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Qin, J.; Ma, Q.; Qiao, K.; Fan, S.; Qu, Y.L. Integrative GWAS and transcriptomics reveal GhAMT2 as a key regulator of cotton resistance to Verticillium wilt. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1563466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, N.R.; Coombs, J.J.; Felcher, K.J.; Hammerschmidt, R.; Zuehlke, M.L.; Buell, C.R.; Douches, D.S. Genome-wide association analysis of common scab resistance and expression profiling of tubers in response to thaxtomin A treatment underscore the complexity of common scab resistance in tetraploid potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 2020, 97, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Mu, X.; Liu, C.; Cai, J.; Shi, K.; Zhu, W.; Yang, Q. Overexpression of potato miR482e enhanced plant sensitivity to Verticillium dahliae infection. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2015, 57, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Chen, X.; Yi, X.; Fu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Lyu, D. Identification of a Highly Virulent Verticillium nonalfalfae Strain Vn011 and Expression Analysis of Its Orphan Genes During Potato Inoculation. Plants 2025, 14, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Dong, B.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, J. The Study on Biological Characteristics of GFP Labeled Potato Verticillium dahliae. Acta Agric. Boreali-Sin. 2016, 31, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. GFP Tagged Potato Verticiliium dahliae Kleb and Its Infection Process in Potato. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Futschik, M.E. Noise-robust soft clustering of gene expression time-course data. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2005, 3, 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shreejana, K.C.; Poudel, A.; Oli, D.; Ghimire, S.; Angon, P.B.; Islam, M.S. A comprehensive assessment of Verticillium wilt of potato: Present status and future prospective. Int. J. Phytopathol. 2023, 12, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarazo, I.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Cristancho, O.; Olaya, F.; Duarte, M. Identification of symptoms related to potato Verticillium wilt from UAV-based multispectral imagery using an ensemble of gradient boosting machines. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 3, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, T.R.; Cesarino, I.; Oliveira, D.M. Xylan engineering in vascular tissue for biomass valorization. Trends Plant Sci. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tu, M.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Messing, J. Common Metabolic networks Contribute to Carbon Sink Strength of Sorghum Internodes: Implications for Bioenergy Improvement. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Gu, M.; Lai, Z.; Fan, B.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J.; Chen, Z. Functional Analysis of the Arabidopsis PAL Gene Family in Plant Growth, Development, and Response to Environmental Stress. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1526–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonnessen, B.W.; Manosalva, P.; Lang, J.M.; Baraoidan, M.; Bordeos, A.; Mauleon, R.; Oard, J.; Hulbert, S.; Leung, H.; Leach, J.L. Rice phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene OsPAL4 is associated with broad spectrum disease resistance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015, 87, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Hou, Q.; Lv, H.; Shi, H.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, M.; He, M.; Yin, J.; et al. D53 represses rice blast resistance by directly targeting phenylalanine ammonia lyases. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1827–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Dong, L.; Wu, J.; Cheng, Q.; Qi, D.; Yan, X.; Jiang, L.; Fan, S.; et al. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase2.1 contributes to the soybean response towards Phytophthora sojae infection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Hwang, B.K. An important role of the pepper phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene (PAL1) in salicylic acid-dependent signalling of the defence response to microbial pathogens. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Li, N. Genome-wide identification and expression analyses of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene family members from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) reveal their role in root-knot nematode infection. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1204990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Wang, R.; Shi, F.; Zeng, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; et al. Integrative gene duplication and genome-wide analysis as an approach to facilitate wheat reverse genetics: An example in the TaCIPK family. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 61, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, D.; Duan, M.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Yang, C.; Qiu, Z.; Liu, D.; Wen, P.; et al. An R2R3 MYB transcription factor confers brown planthopper resistance by regulating the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase pathway in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Fang, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, G.; Ning, Y. Phenylalanine ammonia lyases mediate broad-spectrum resistance to pathogens and insect pests in plants. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 1425–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.; Li, K.; Wang, B.; Chen, W.; Guo, B.; Qiao, L.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, F. OsPRMT5 methylates OsPAL1 to promote rice resistance, hindered by a Xanthomonas oryzae effector. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 1599–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daayf, F.; Nicole, M.; Belanger, R.R.; Geiger, J.P. Hyaline mutants from Verticillium dahliae, an example of selection and characterization of strains for host–parasite interaction studies. Plant Pathol. 1998, 47, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Jia, R.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J. Evaluation of Resistance to Verticillium Wilt in Different Potato Cultivars under Indoor Conditions. J. Inn. Mong. Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, J. Identification of the vegetative compatibility groups (VCGs), races, mating types, and pathogenicity differentiation of pathogenic bacteria of potato Verticillium wilt. J. Plant Prot. 2018, 45, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, F.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Sun, L.; Bao, N.; Zhang, T.; Cui, C.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Jasmonate-mediated wound signalling promotes plant regeneration. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira, F.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Lee, J.; Eusebi, A.; Niewielska, A.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Lopez, R.; Butcher, S. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acid Res. 2024, 52, W521–W525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Feng, Y.; Tu, M.; Wittich, P.E.; Bate, N.J.; Messing, J. Transcriptome and Metabolome Reveal Distinct Carbon Allocation Patterns During Internode Sugar Accumulation in Different Sorghum Genotypes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zeng, J.; Du, C.; Tang, Q.; Hua, Y.; Chen, M.; Yang, G.; Tu, M.; He, G.; Li, Y.; et al. Divergent Roles of the Auxin Response Factors in Lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus (Nees ex Steud.) W. Watson) during Plant Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comparison Group | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Total No. of DEGs | No. of Upregulated DEGs | No. of Downregulated DEGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SP_1T vs | SP_1C | 1060 | 461 | 599 |

| 2 | SP_3T vs | SP_3C | 751 | 371 | 380 |

| 3 | SP_5T vs | SP_5C | 663 | 374 | 289 |

| 4 | SP_13T vs | SP_13C | 3075 | 327 | 2748 |

| 5 | SP_1C vs | SP_0 | 3718 | 2130 | 1588 |

| 6 | SP_1T vs | SP_0 | 2311 | 1456 | 855 |

| 7 | SP_3C vs | SP_1C | 1855 | 1019 | 836 |

| 8 | SP_3T vs | SP_1T | 996 | 522 | 474 |

| 9 | SP_5C vs | SP_3C | 97 | 50 | 47 |

| 10 | SP_5T vs | SP_3T | 318 | 193 | 125 |

| 11 | SP_13C vs | SP_5C | 6948 | 6572 | 376 |

| 12 | SP_13T vs | SP_5T | 299 | 164 | 135 |

| 13 | LS8_1T vs | LS8_1C | 1419 | 844 | 575 |

| 14 | LS8_3T vs | LS8_3C | 1351 | 389 | 962 |

| 15 | LS8_5T vs | LS8_5C | 1654 | 516 | 1138 |

| 16 | LS8_13T vs | LS8_13C | 1315 | 719 | 596 |

| 17 | LS8_1C vs | LS8_0 | 1107 | 564 | 543 |

| 18 | LS8_1T vs | LS8_0 | 1195 | 769 | 426 |

| 19 | LS8_3C vs | LS8_1C | 1453 | 1089 | 364 |

| 20 | LS8_3T vs | LS8_1T | 993 | 474 | 519 |

| 21 | LS8_5C vs | LS8_3C | 147 | 67 | 80 |

| 22 | LS8_5T vs | LS8_3T | 2005 | 1235 | 770 |

| 23 | LS8_13C vs | LS8_5C | 3726 | 1590 | 2136 |

| 24 | LS8_13T vs | LS8_5T | 1788 | 1012 | 776 |

| 25 | LS8_1T vs | SP_1T | 25,799 | 13,378 | 12,421 |

| 26 | LS8_3T vs | SP_3T | 26,031 | 13,035 | 12,996 |

| 27 | LS8_5T vs | SP_5T | 27,072 | 14,084 | 12,988 |

| 28 | LS8_13T vs | SP_13T | 12,986 | 5546 | 7440 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fan, G.; Ren, Z.; Gao, Y.; Di, G.; Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Tu, M.; Li, Y.; Han, S. Time-Series Comparative Transcriptome Analyses of Two Potato Cultivars with Different Verticillium Wilt Resistance. Plants 2026, 15, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010026

Fan G, Ren Z, Gao Y, Di G, Wang P, Zhang S, Zhang W, Tu M, Li Y, Han S. Time-Series Comparative Transcriptome Analyses of Two Potato Cultivars with Different Verticillium Wilt Resistance. Plants. 2026; 15(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Guoquan, Zhiguo Ren, Yanling Gao, Guili Di, Peng Wang, Shu Zhang, Wei Zhang, Min Tu, Yin Li, and Shuxin Han. 2026. "Time-Series Comparative Transcriptome Analyses of Two Potato Cultivars with Different Verticillium Wilt Resistance" Plants 15, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010026

APA StyleFan, G., Ren, Z., Gao, Y., Di, G., Wang, P., Zhang, S., Zhang, W., Tu, M., Li, Y., & Han, S. (2026). Time-Series Comparative Transcriptome Analyses of Two Potato Cultivars with Different Verticillium Wilt Resistance. Plants, 15(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010026