Real-Time Callus Instance Segmentation in Plant Tissue Culture Using Successive Generations of YOLO Architectures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

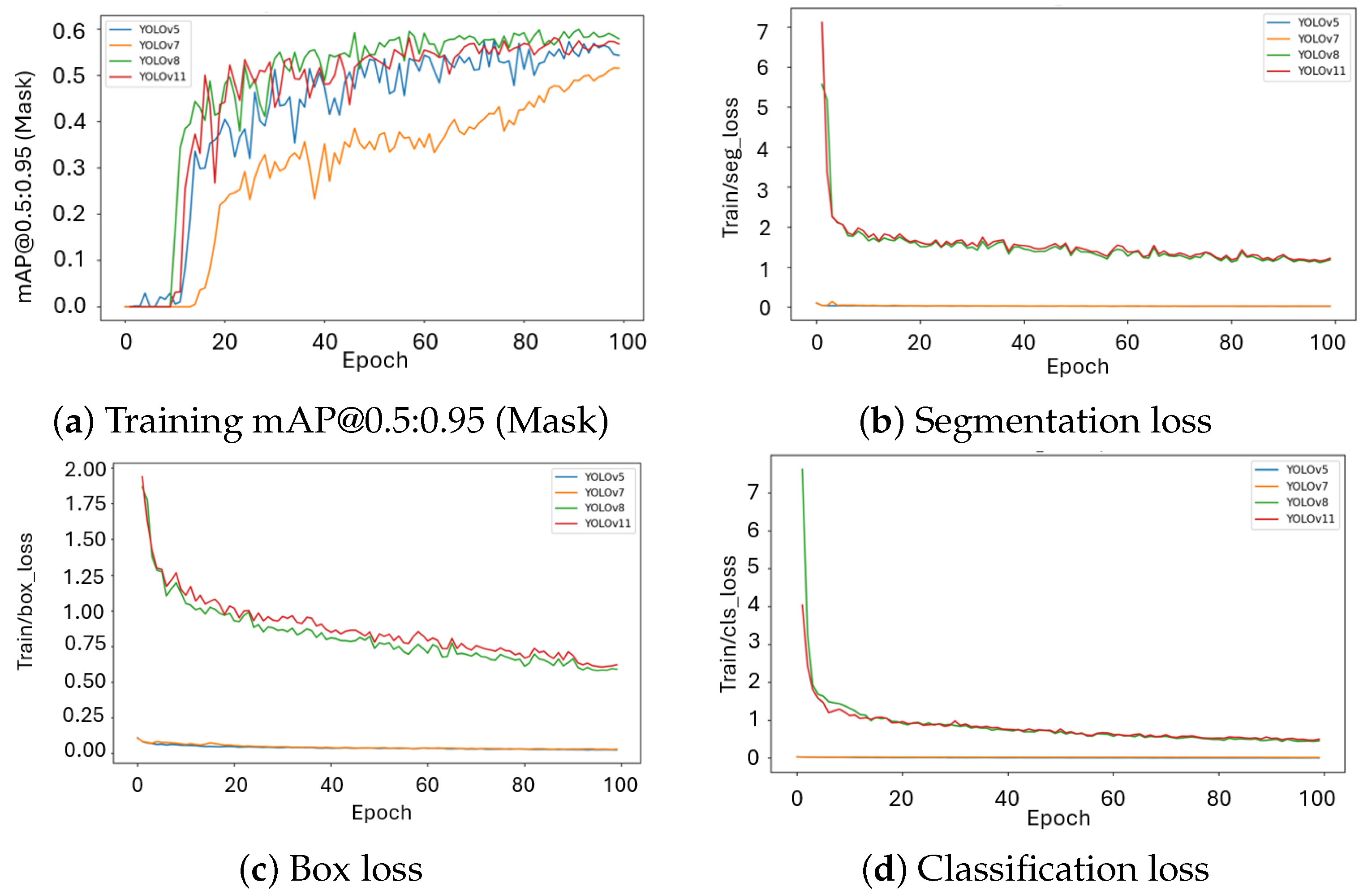

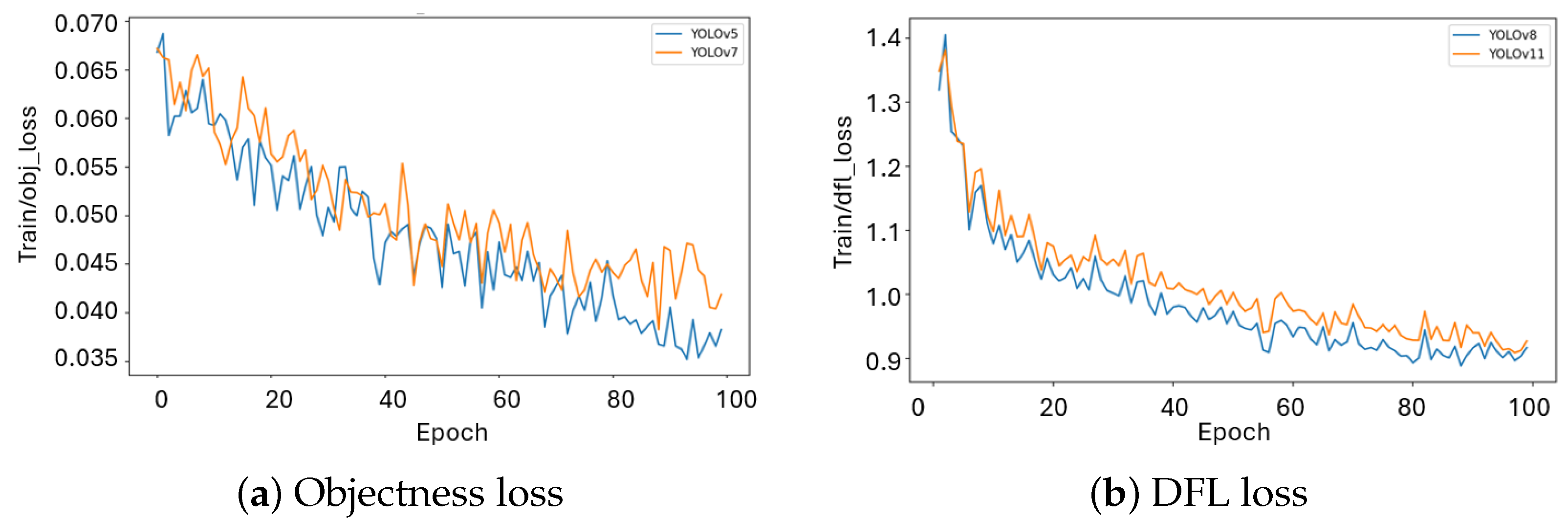

2.1. Runtime, Convergence, and Training Dynamics

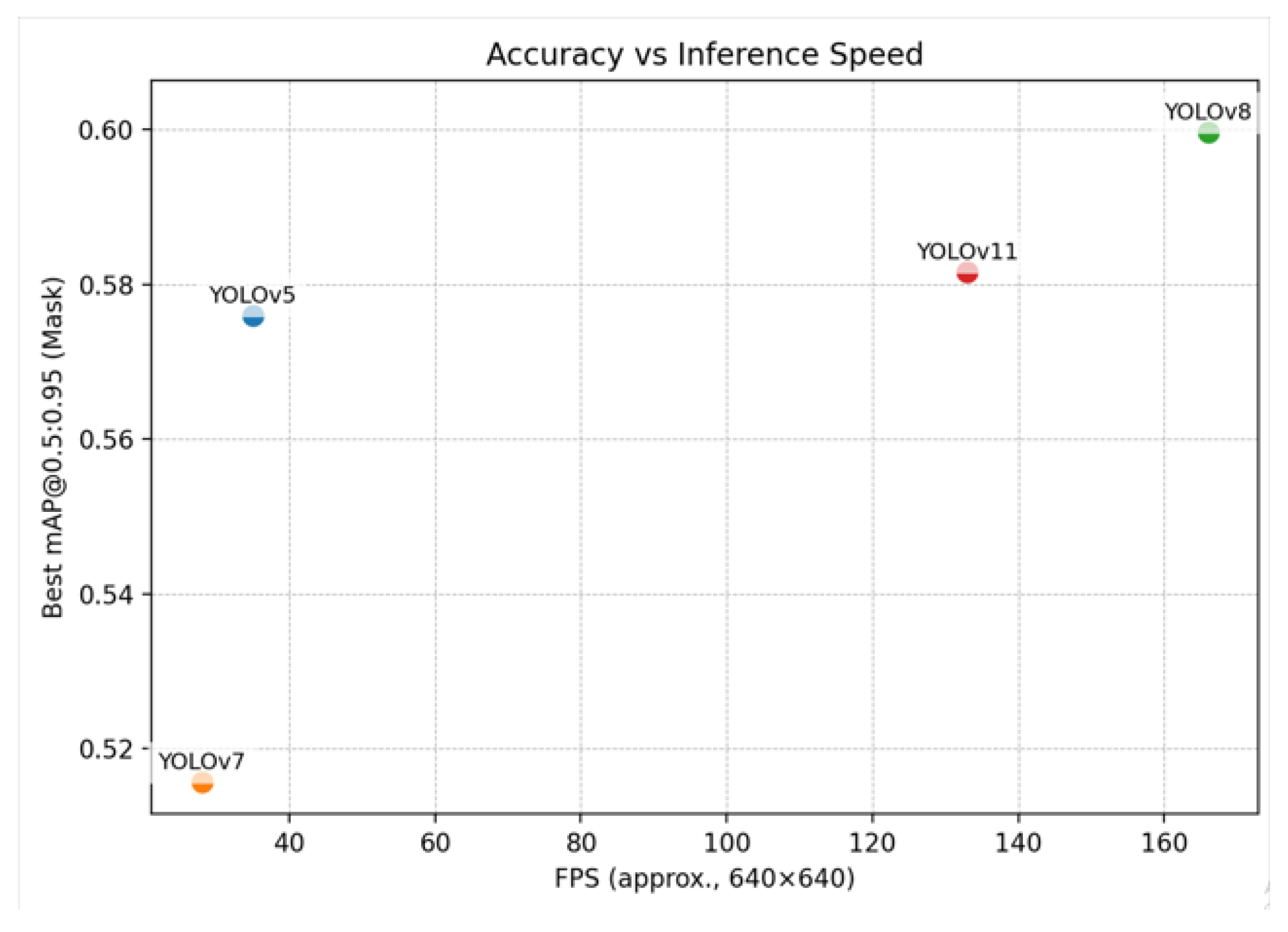

2.2. Segmentation Accuracy and Efficiency Metrics

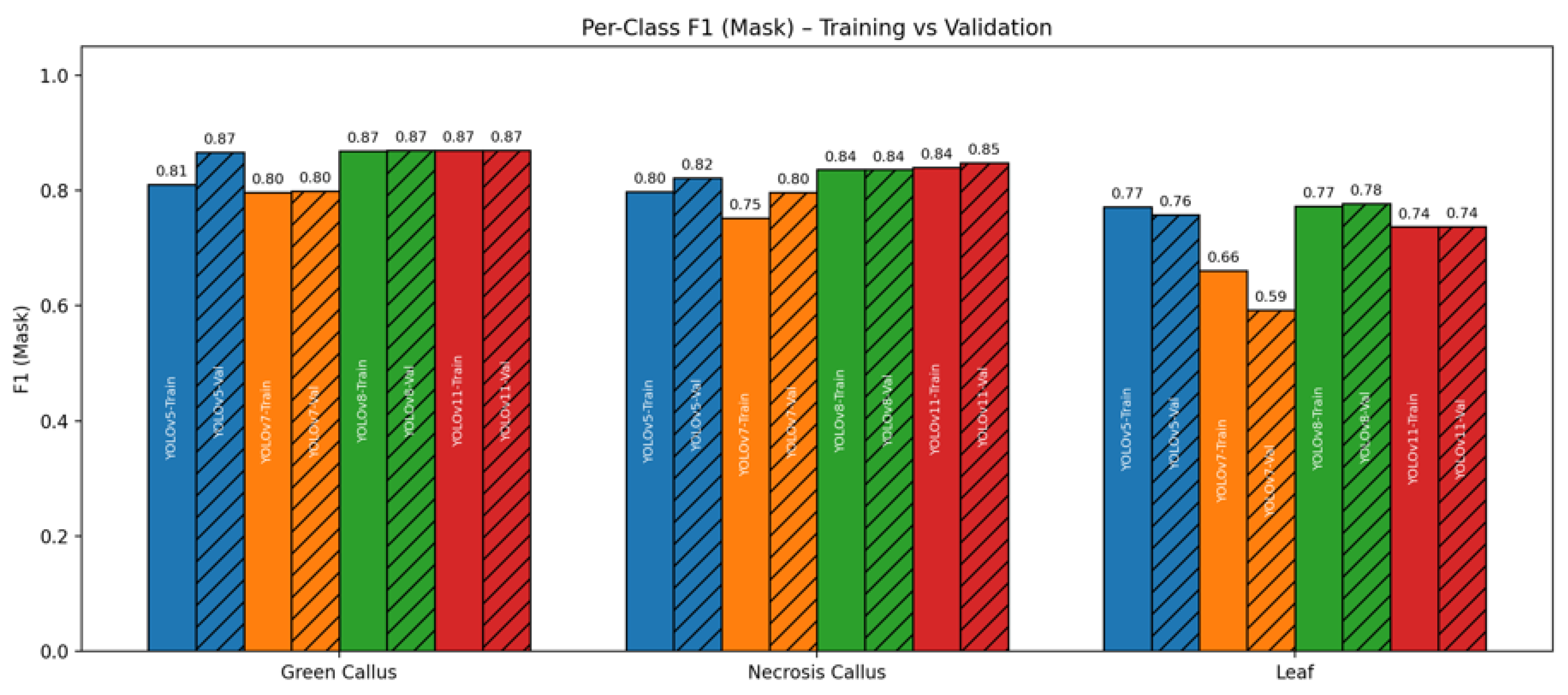

2.3. Class-Level Performance

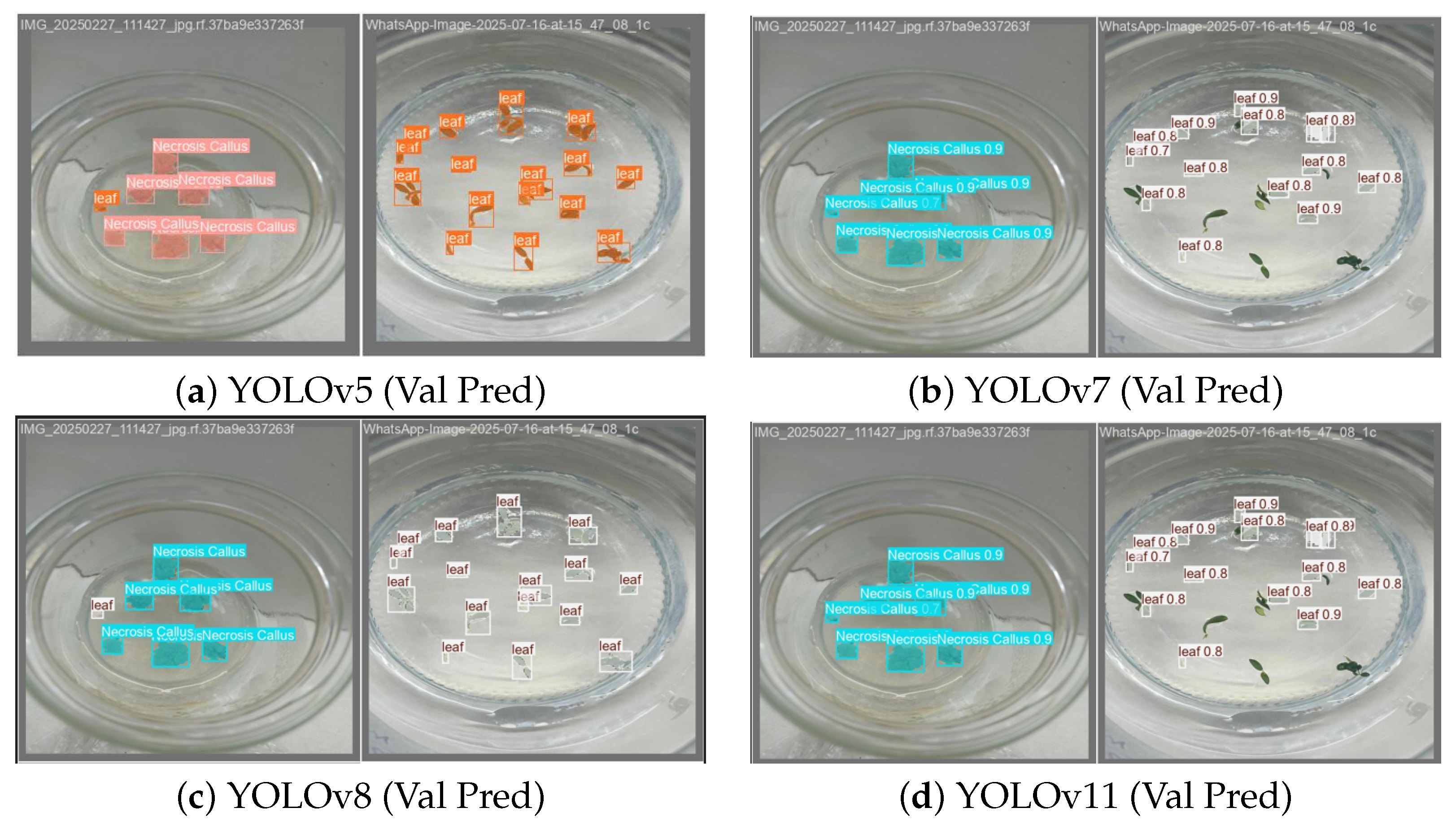

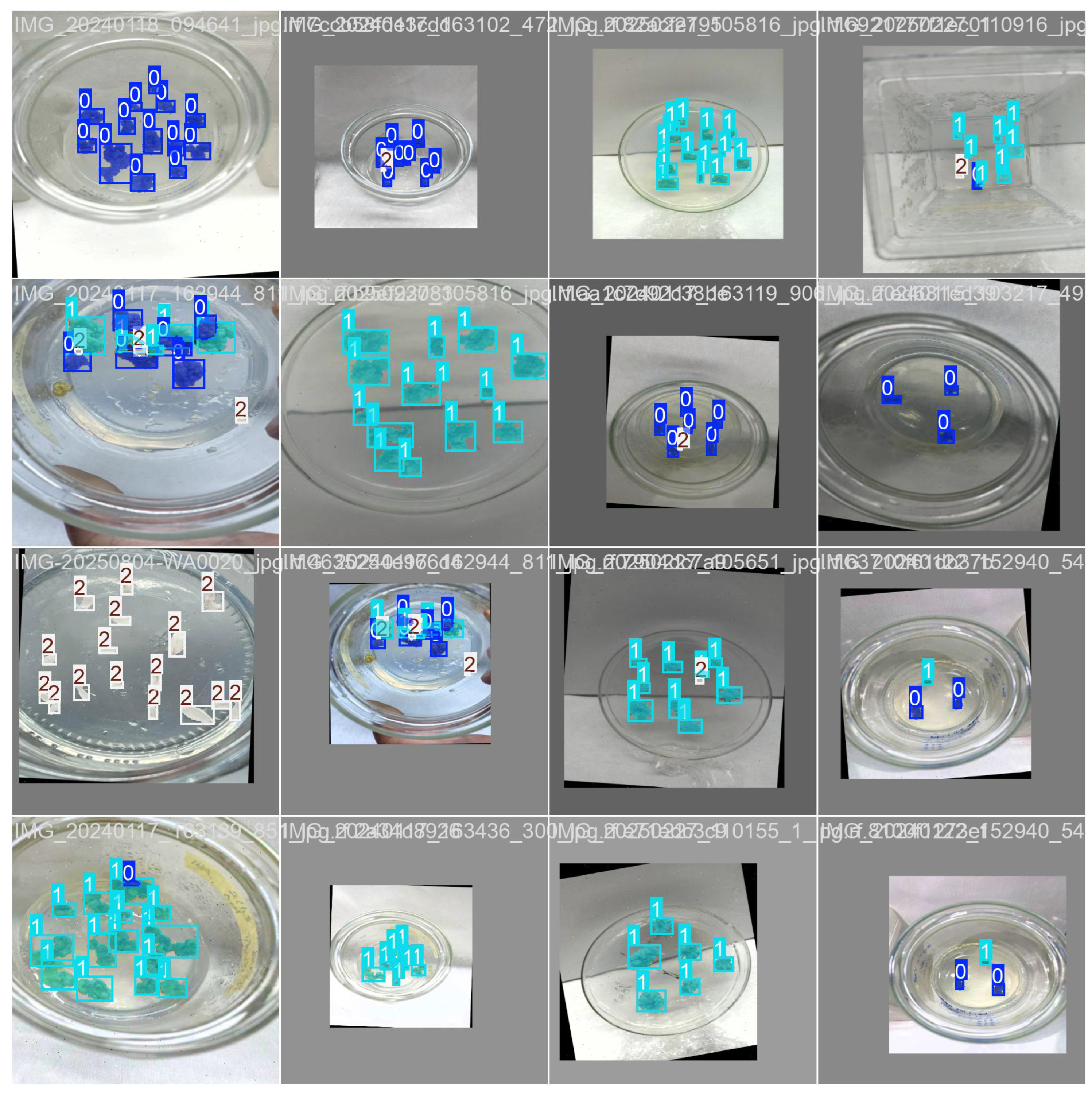

2.4. Comparative Prediction Performance and Key Insights

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

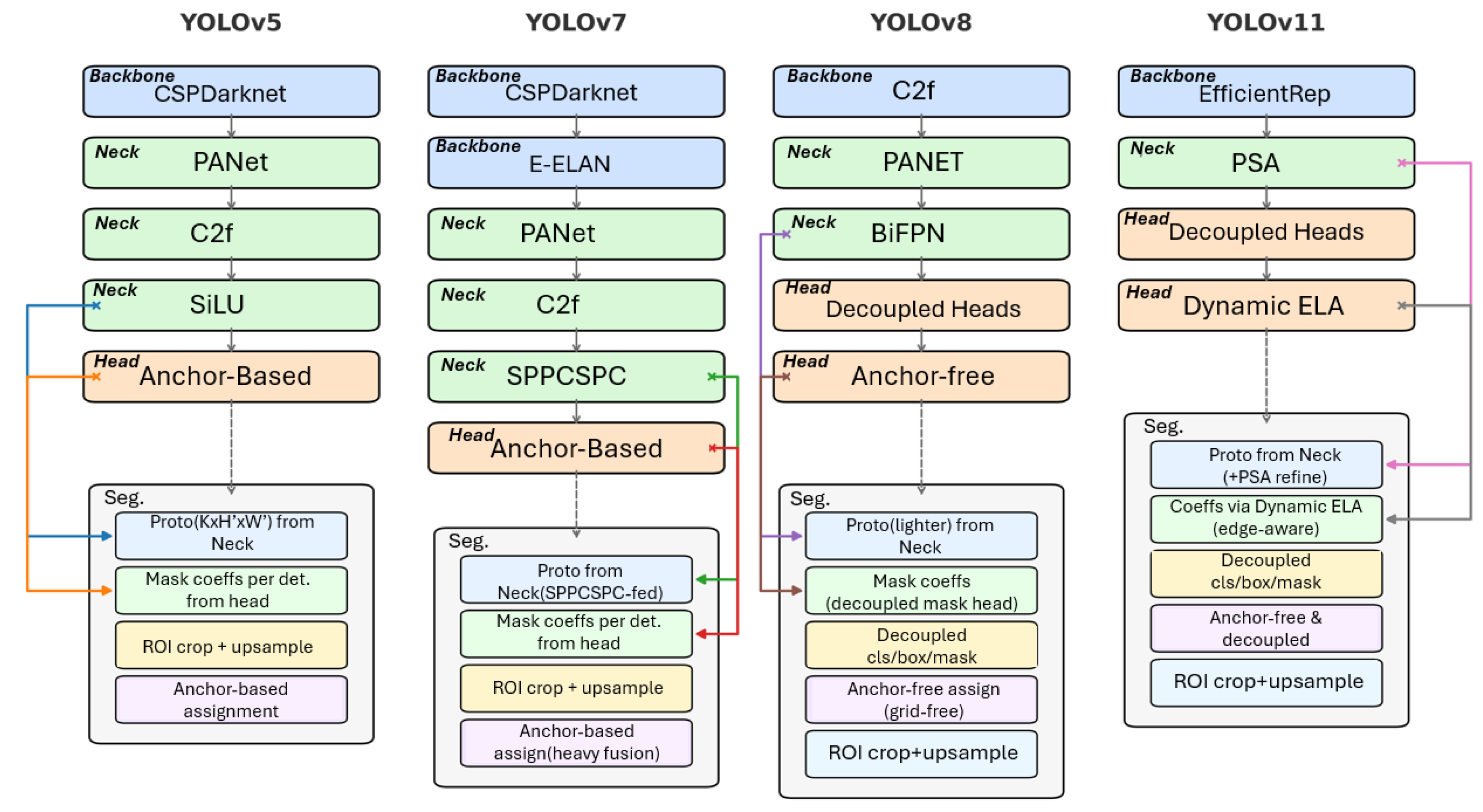

4.1. Successive Generations of YOLO Architectures

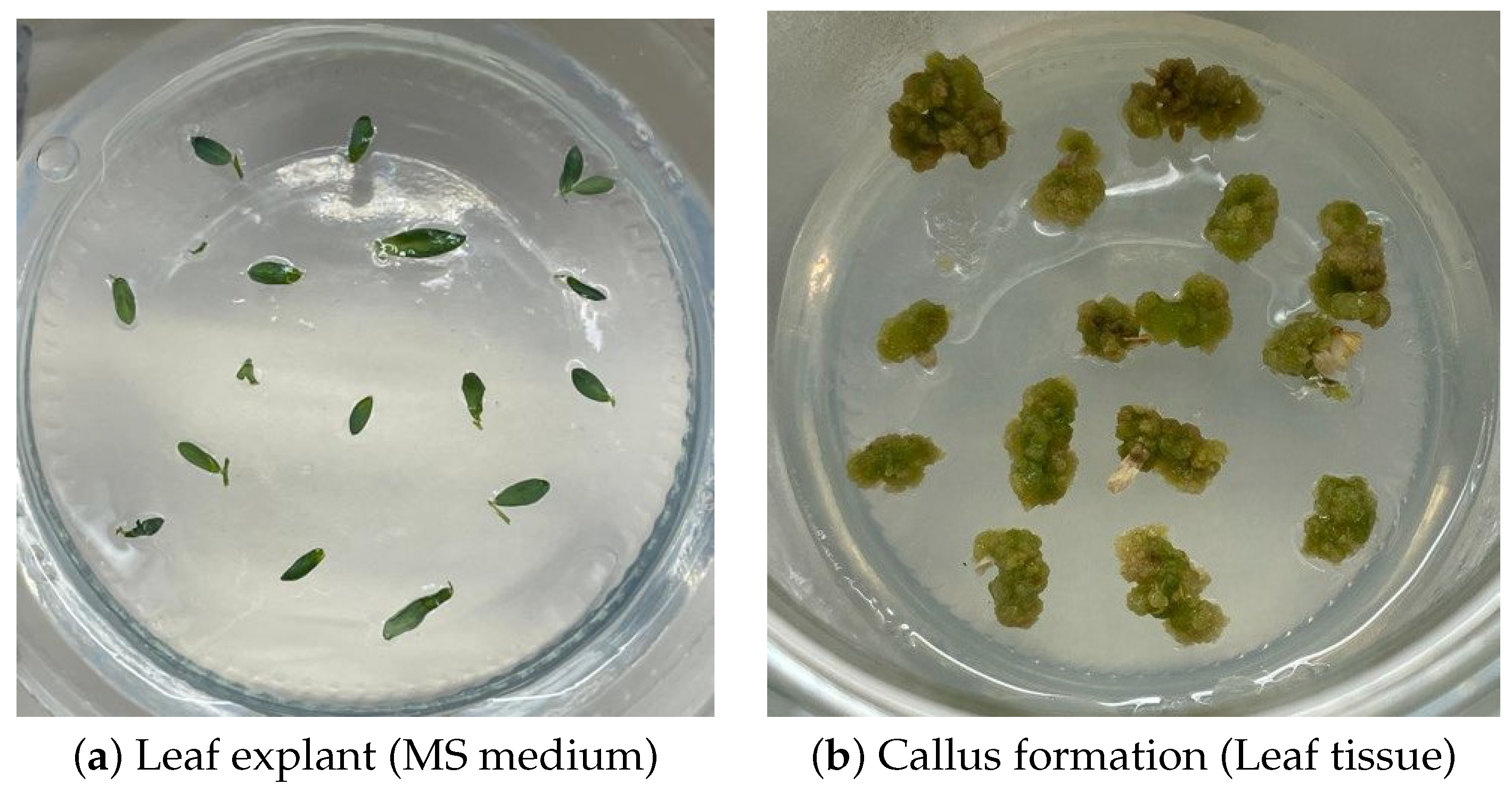

4.2. Plant Material

4.3. Callus Induction

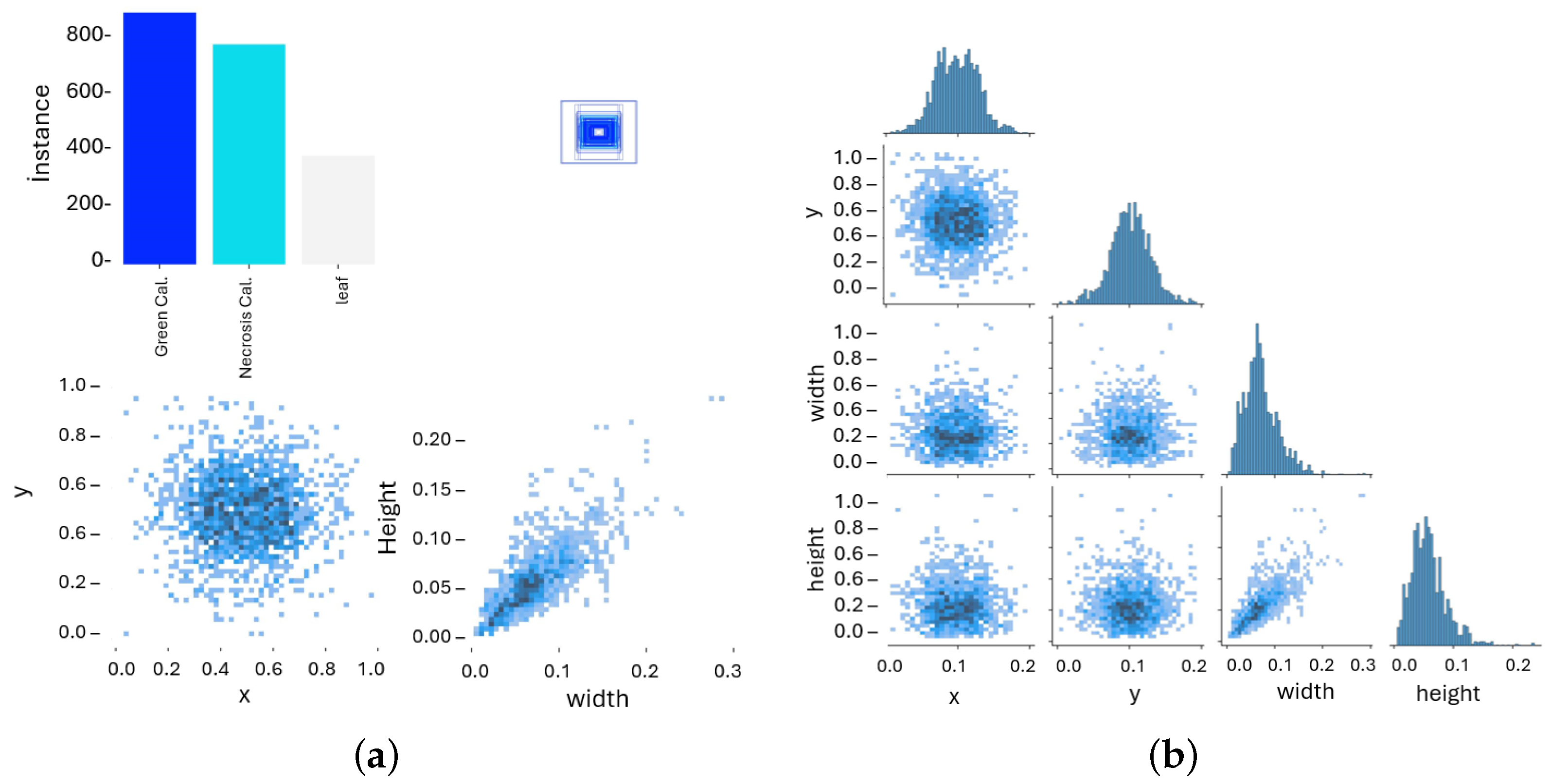

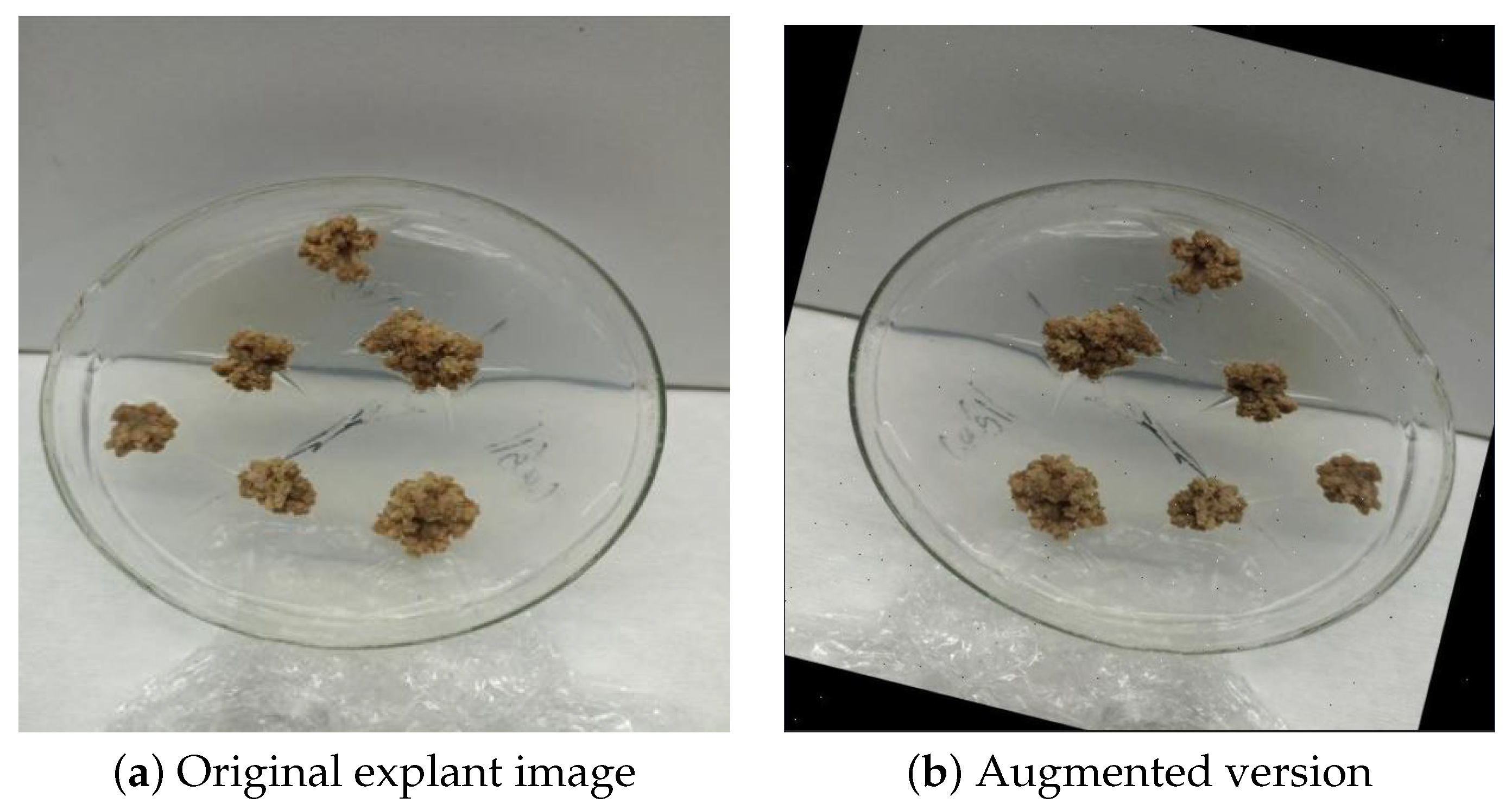

4.4. Dataset Preparation and Augmentation

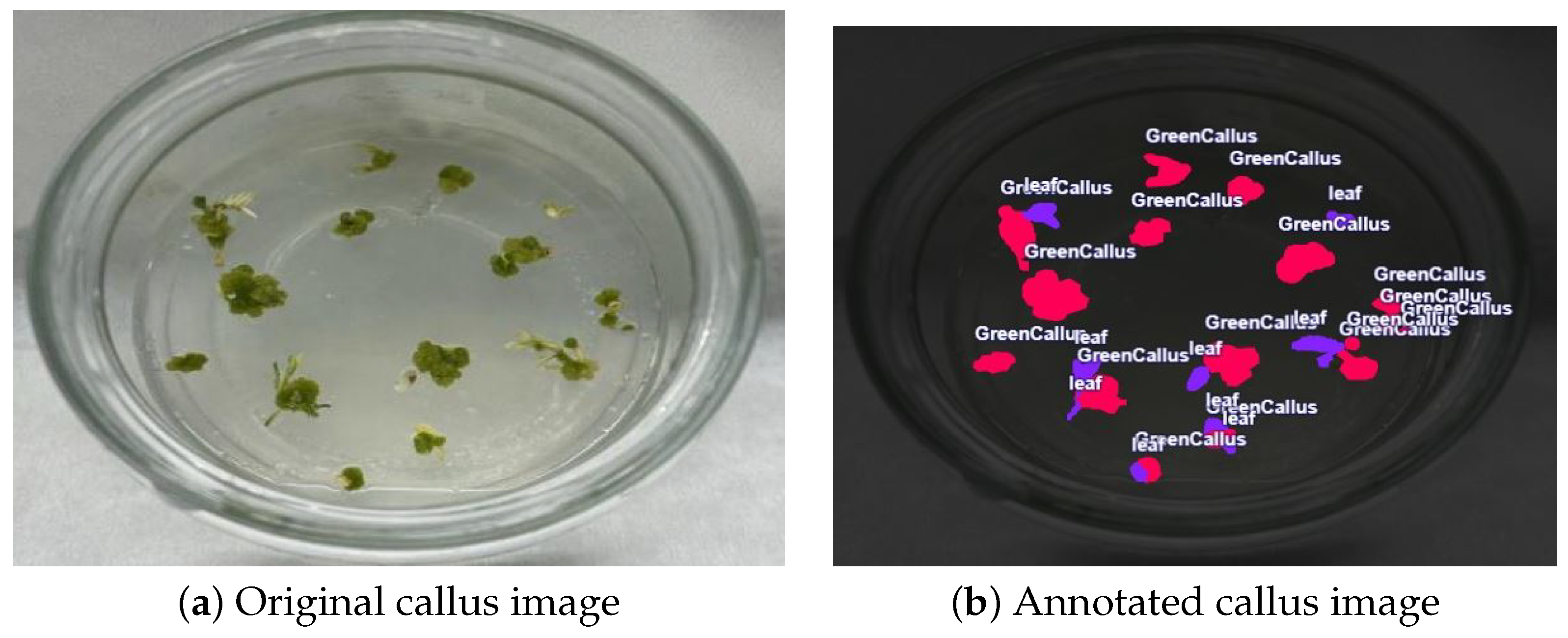

4.5. Evaluation Metrics

4.6. Computational Setup

4.6.1. Computational Environment

4.6.2. Training Configuration

4.6.3. Model-Specific Setup

4.6.4. Statistical Significance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BAP | 6-benzylaminopurine |

| BiFPN | Bi-directional Feature Pyramid Network |

| C2f | Cross-Stage Partial with two convolutions and feature reuse |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CSPDarknet | Cross-Stage Partial Darknet |

| ELA | Edge-aware Localization Adjustment |

| E-ELAN | Extended Efficient Layer Aggregation Network |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| FLOPs | Floating Point Operations |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| MS medium | Murashige and Skoog nutrient medium |

| NAA | Naphthaleneacetic Acid |

| PANet | Path Aggregation Network |

| PSA | Parallel Spatial Attention |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| SiLU | Sigmoid Linear Unit |

| SPPCSPC | Spatial Pyramid Pooling with Cross-Stage Partial connections |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Thorpe, T.A. History of plant tissue culture. Mol. Biotechnol. 2007, 37, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, T.P.; Steinmacher, D. Plant Growth Regulation in Cell and Tissue Culture In Vitro. Plants 2024, 13, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, T.; Takebe, I. Plating of isolated tobacco mesophyll protoplasts on agar medium. Planta 1971, 99, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehér, A. Callus, dedifferentiation, totipotency, somatic embryogenesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The International Year of Pulses: Final Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/a5ba05a4-314c-4d73-a47e-1dd8c6021258 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Bagheri, A.; Ghasemi Omraan, V.O.; Hatefi, S. Indirect in vitro regeneration of lentil. J. Plant Mol. Breeding 2012, 1, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Kamilaris, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 147, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alif, M.; Hussain, S. YOLO object detection algorithms from v1 to v10: A review with applications. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2024, 8, 100091. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object Detection in 20 Years: A Survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Tan, F. SWRD-YOLO: A Lightweight Instance Segmentation Model for Estimating Rice Lodging Degree in UAV Remote Sensing Images with Real-Time Edge Deployment. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Olivier, K.; Chen, L. An Automated Image Segmentation, Annotation, and Detection Framework Integrating SAM and YOLOv8. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1081. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Lu, R.; Guo, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Hu, X. F-YOLOv8n-seg: A Lightweight Model for Weed Meristem Localization. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2121. [Google Scholar]

- Sonawane, D.; Patil, S. Crop–Weed Segmentation Using YOLOv8 for Smart Farming. Smart Agric. Syst. 2025, 2, 100078. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, R.; Karkee, M. Comparing YOLOv11 and YOLOv8 for Instance Segmentation of Immature Green Fruitlets in Orchard Environments. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.19869. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, R.; Hao, C.; Dong, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Xue, X.; Sun, G. YOLOv11-GSF: An optimized deep learning model for strawberry ripeness detection in agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1584669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.T.; Jensen, S.M. Leaf Segmentation across Multiple Crops Using YOLOv11. Agriculture 2025, 15, 196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, D.; Wei, Y.; Wang, P.; Su, M. YOLOv8-CMS: A High-Accuracy Deep Learning Model for Automated Citrus Leaf Disease Classification and Grading. Plant Methods 2025, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daraghmi, Y.A.; Naser, W.; Daraghmi, E.Y.; Fouchal, H. Drone-Assisted Plant Stress Detection Using Deep Learning. Agronomy 2025, 7, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. FCOS: Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9627–9636. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Krähenbühl, P. Objects as Points. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 1195–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo, J.C.; Goodman, A.; Karhohs, K.W.; Cimini, B.A.; Ackerman, J.; Haghighi, M.; Heng, C.; Becker, T.; Doan, M.; McQuin, C.; et al. Nucleus segmentation across imaging experiments: The 2018 Data Science Bowl. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, E.; Bannon, D.; Kudo, T.; Graf, W.; Covert, M.; Valen, D.V. Deep learning for cellular image analysis. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. YOLOv5: Implementation of You Only Look Once in PyTorch. GitHub Repository. [Online]. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.02696. [Google Scholar]

- Ultralytics. YOLOv8: Next-Generation YOLO Models. Ultralytics Documentation. [Online]. 2023. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Ma, J. YOLOv11-Seg: Instance Segmentation for Construction Site Monitoring. Buildings 2024, 14, 3777. [Google Scholar]

- Polanco, C.; Ruiz, M.L. Efficient in vitro callus induction and plant regeneration of lentil. Plant Cell Rep. 2002, 21, 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Barik, D.P.; Naik, P.; Mohapatra, P.K. In vitro callus induction and plant regeneration in Lens culinaris Medik. Biol. Plant. 2005, 49, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, R.; Shekhawat, A.; Singh, V. Genotypic variability in callus induction and plant regeneration in lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). Legume Res. 2011, 34, 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, A.B.; Islam, S.M.A. Predicting rice callus induction using machine learning models. Plant Tissue Cult. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard, P. Étude comparative de la distribution florale dans une portion des Alpes et des Jura. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 1901, 37, 547–579. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, T. A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content. Biol. Skr. 1948, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Everingham, M.; Gool, L.V.; Williams, C.K.I.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The PASCAL Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, R.; Netto, S.L.; da Silva, E.A.B. A Survey on Performance Metrics for Object-Detection Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Systems, Signals and Image Processing (IWSSIP), Niteroi, Brazil, 1–3 July 2020; pp. 819–829. [Google Scholar]

| Model | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | Mask P | Mask R | Dice | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | Train Time | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5 | 0.831 | 0.573 | 0.863 | 0.750 | 0.803 | 7.4 | 25.7 | 0.214 h | 35 |

| YOLOv7 | 0.772 | 0.515 | 0.797 | 0.682 | 0.734 | 37.9 | 141.9 | 0.652 h | 28 |

| YOLOv8 | 0.855 | 0.599 | 0.877 | 0.781 | 0.826 | 11.8 | 39.9 | 0.214 h | 166 |

| YOLOv11 | 0.832 | 0.581 | 0.851 | 0.782 | 0.816 | 10.1 | 32.8 | 0.214 h | 133 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Egi, Y.; Oter, T.; Hajyzadeh, M.; Catak, M. Real-Time Callus Instance Segmentation in Plant Tissue Culture Using Successive Generations of YOLO Architectures. Plants 2026, 15, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010047

Egi Y, Oter T, Hajyzadeh M, Catak M. Real-Time Callus Instance Segmentation in Plant Tissue Culture Using Successive Generations of YOLO Architectures. Plants. 2026; 15(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgi, Yunus, Tülay Oter, Mortaza Hajyzadeh, and Muammer Catak. 2026. "Real-Time Callus Instance Segmentation in Plant Tissue Culture Using Successive Generations of YOLO Architectures" Plants 15, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010047

APA StyleEgi, Y., Oter, T., Hajyzadeh, M., & Catak, M. (2026). Real-Time Callus Instance Segmentation in Plant Tissue Culture Using Successive Generations of YOLO Architectures. Plants, 15(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010047