Integrative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis Provides New Insights into the Multifunctional ARGONAUTE 1 Through an Arabidopsis ago1-38 Mutant with Pleiotropic Growth Defects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

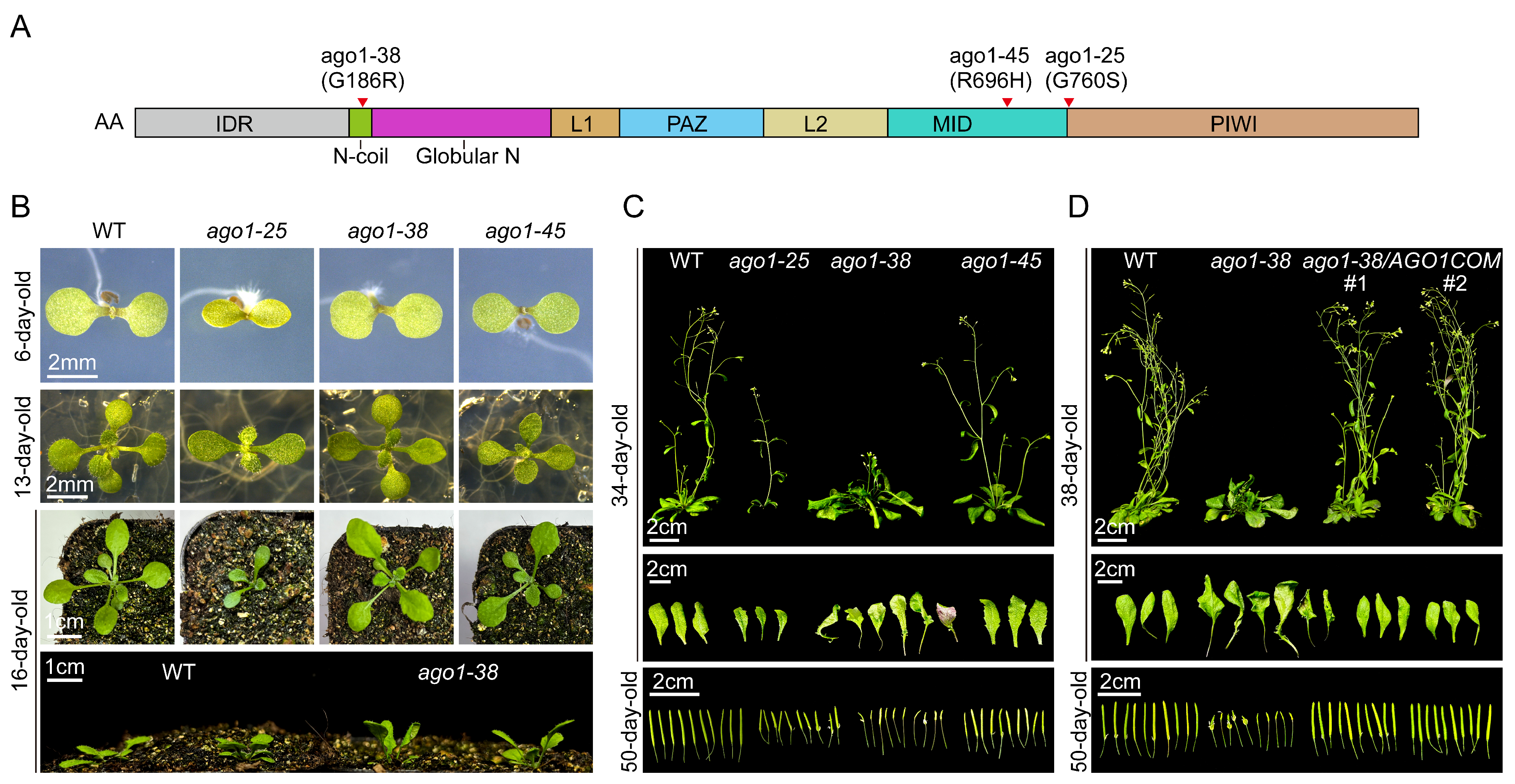

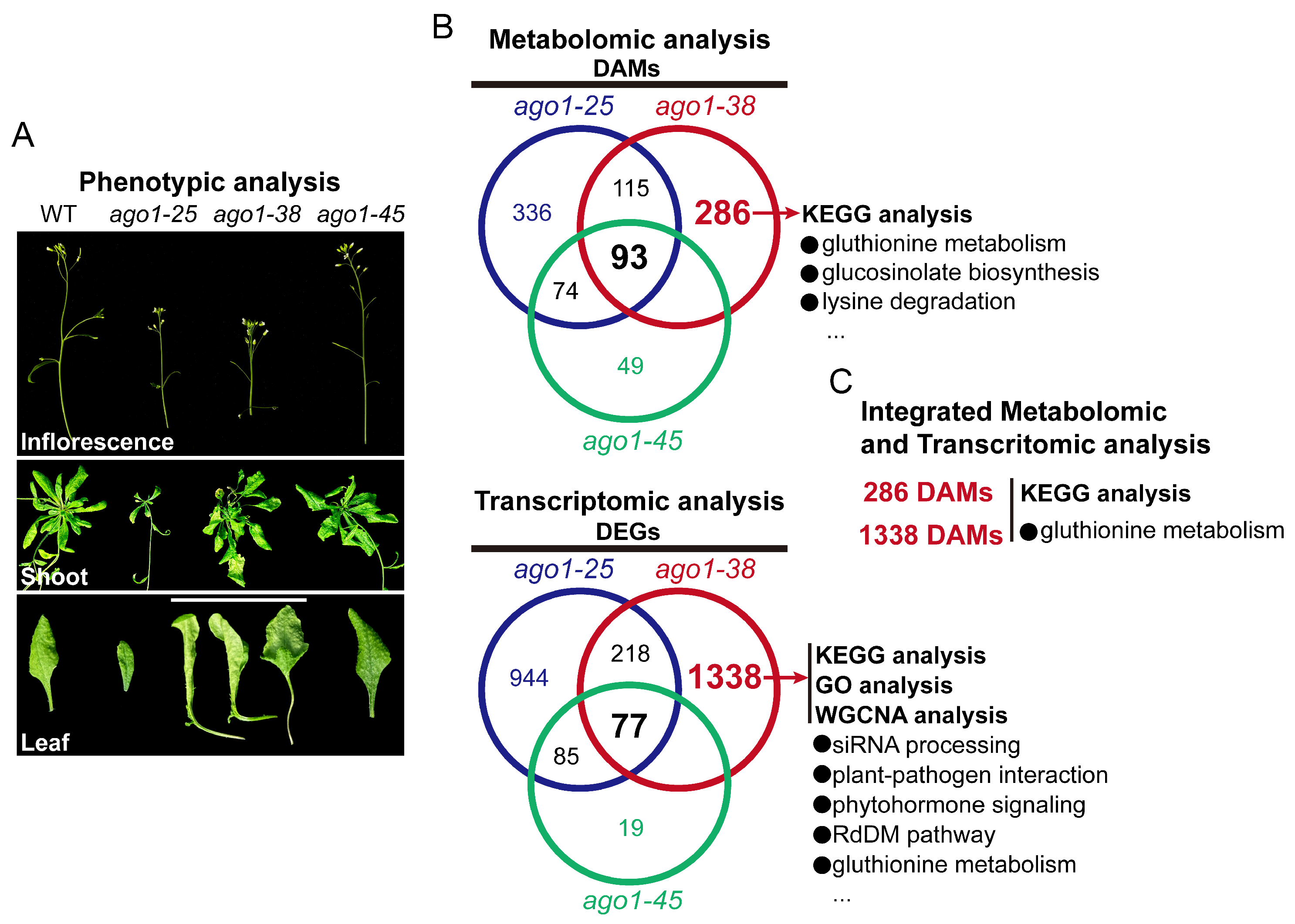

2.1. The Peculiar Phenotype of the ago1-38 Allele

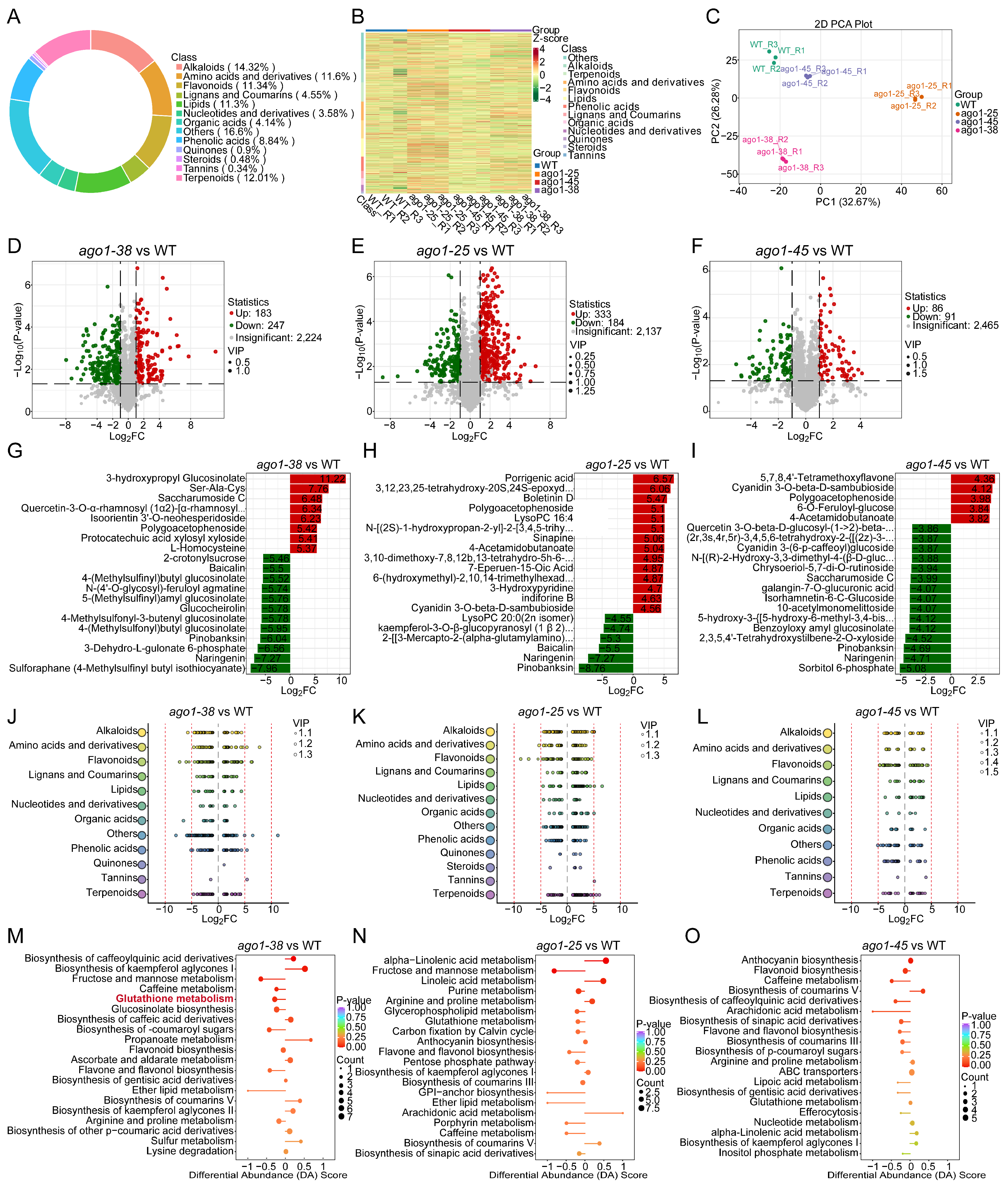

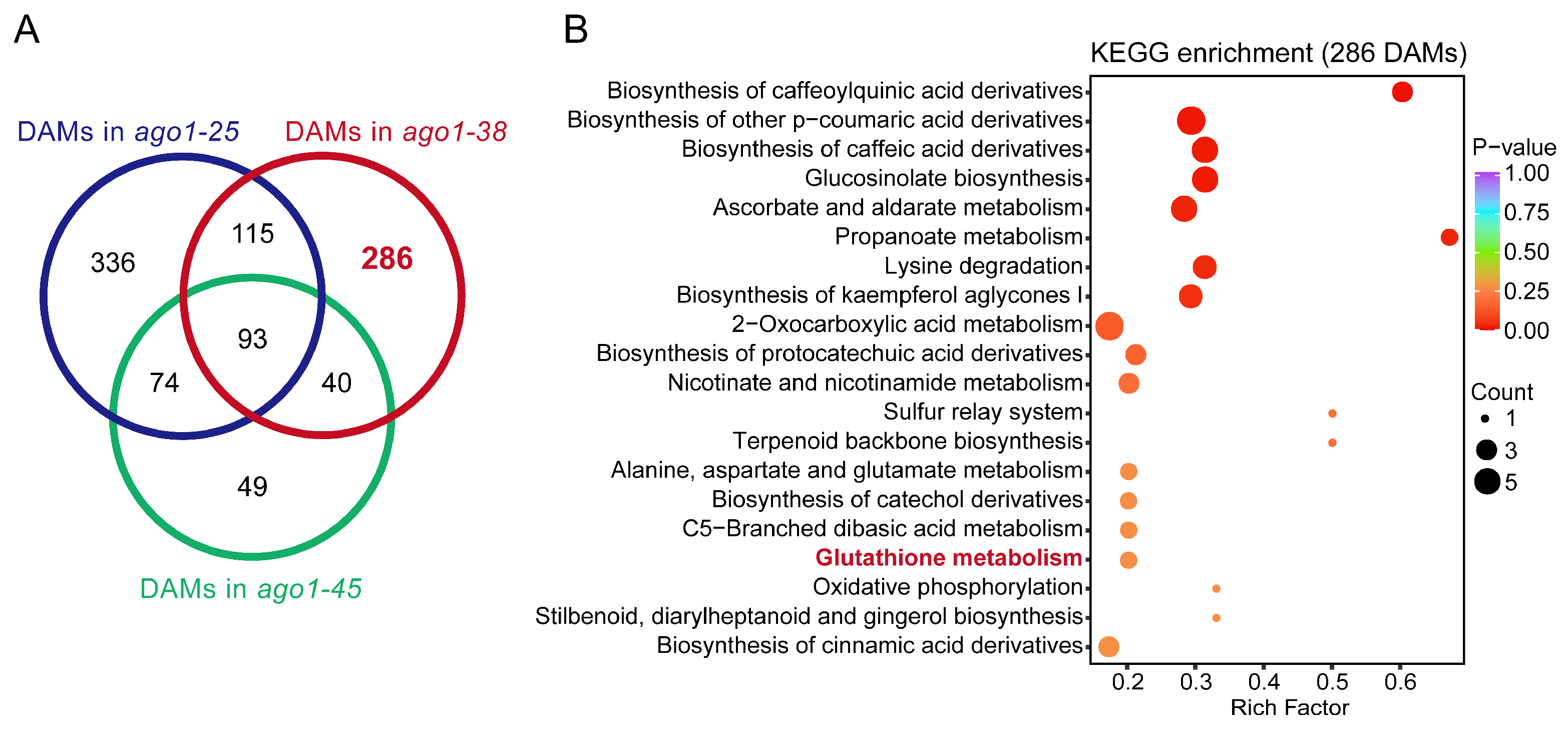

2.2. Metabolome Profiling of Three ago1 Mutants

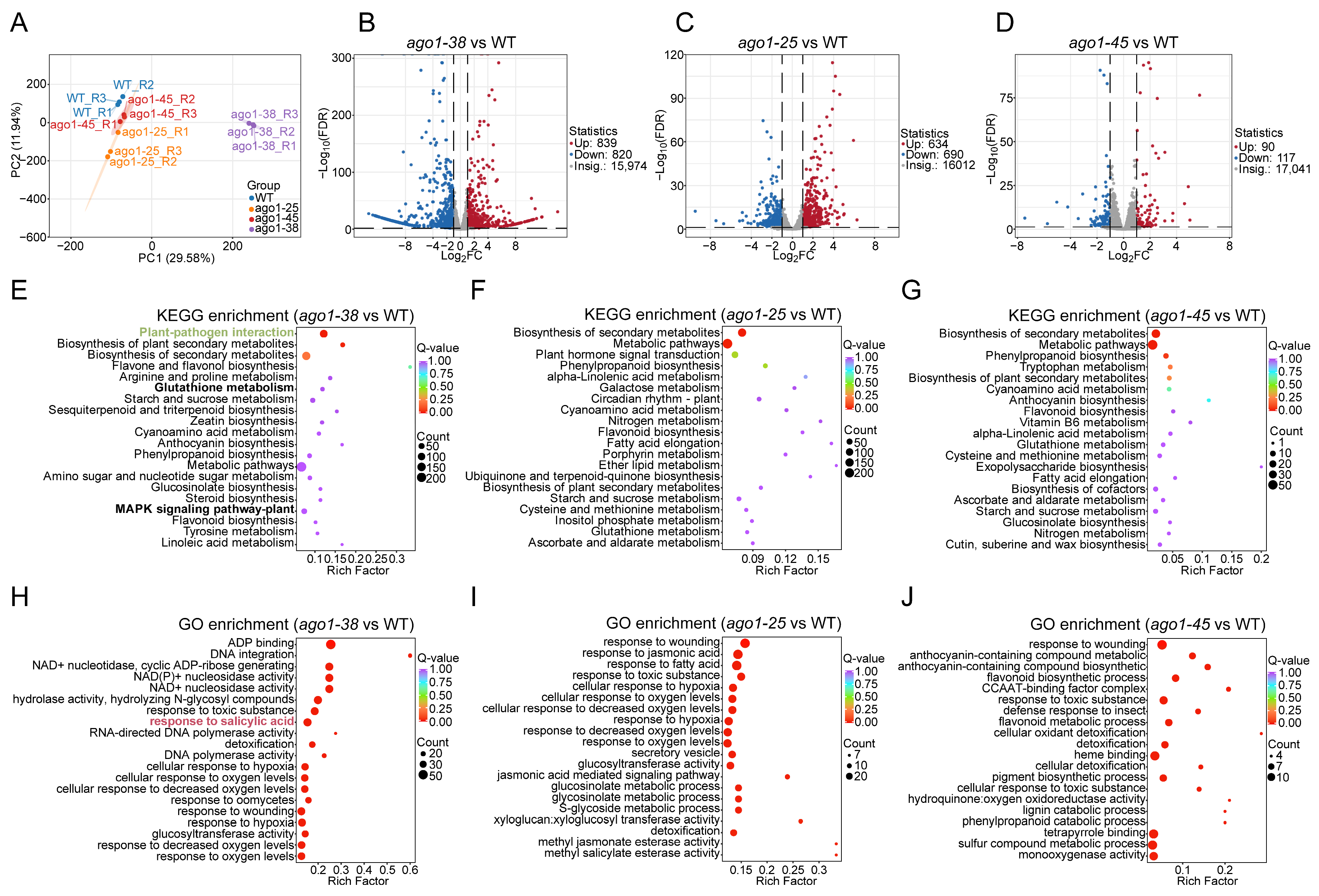

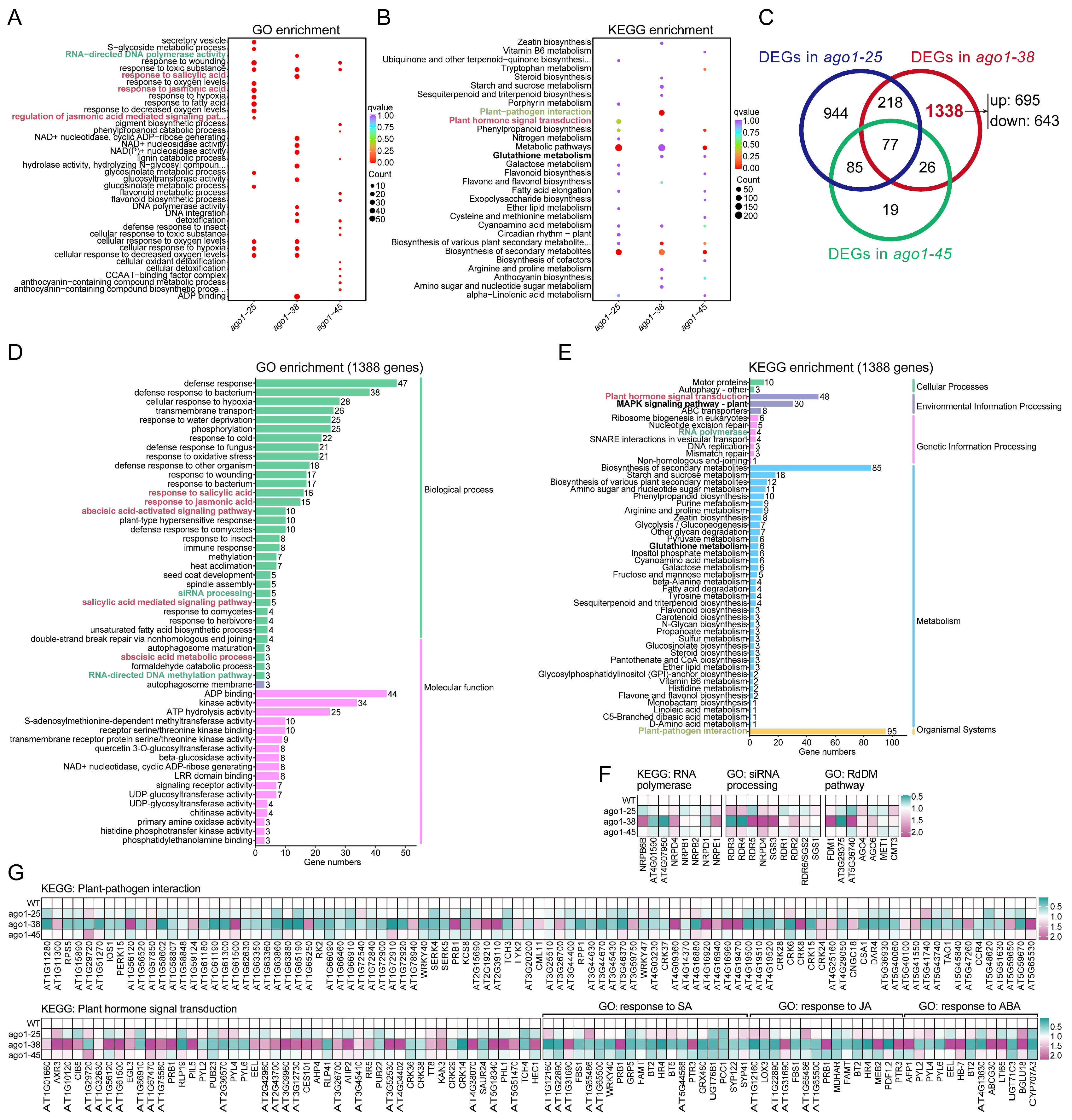

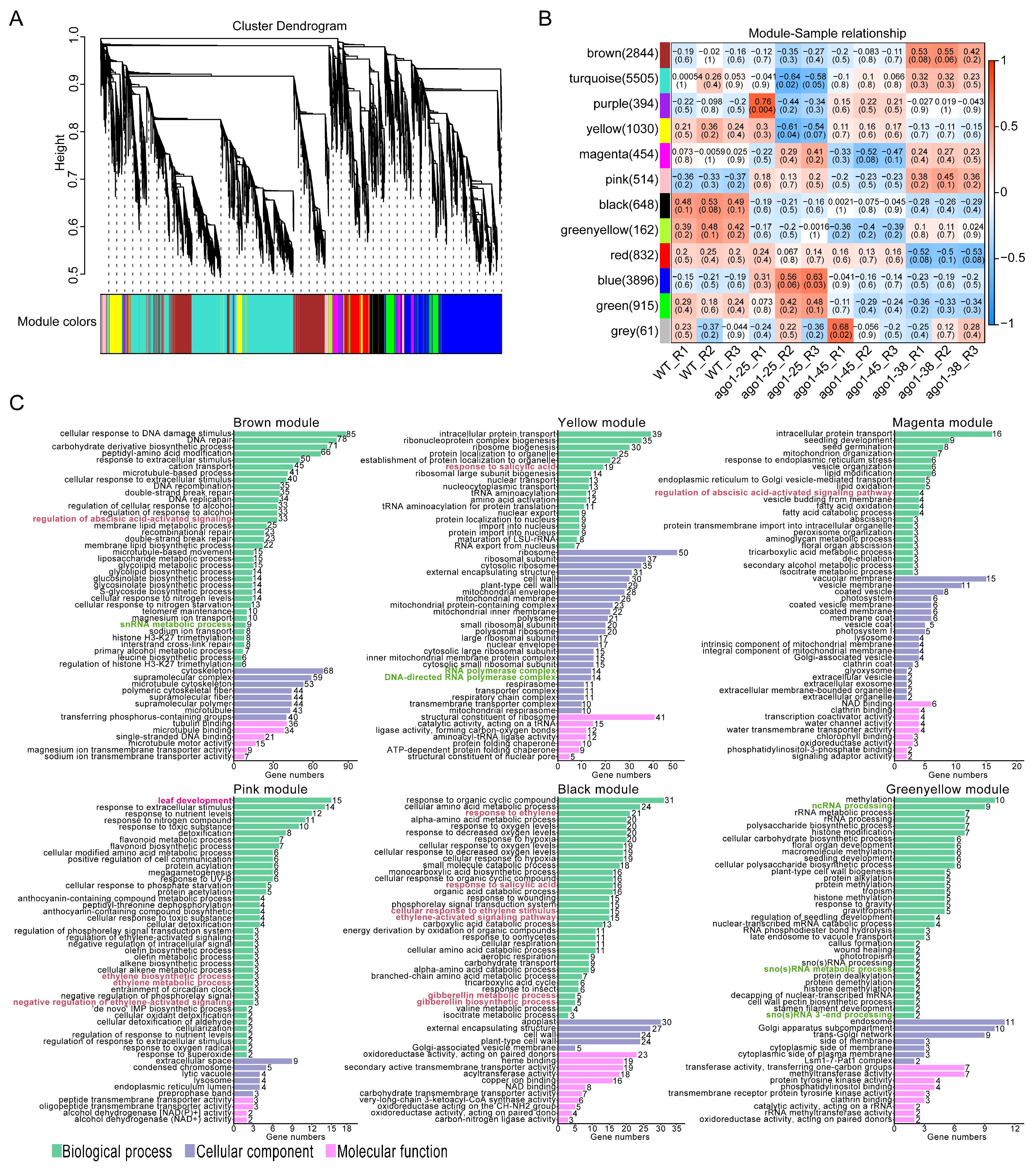

2.3. Transcriptomic Profiling of Three ago1 Mutants

2.4. The G186R Substitution in ago1-38 Does Not Affect Its Gene-Binding Activity

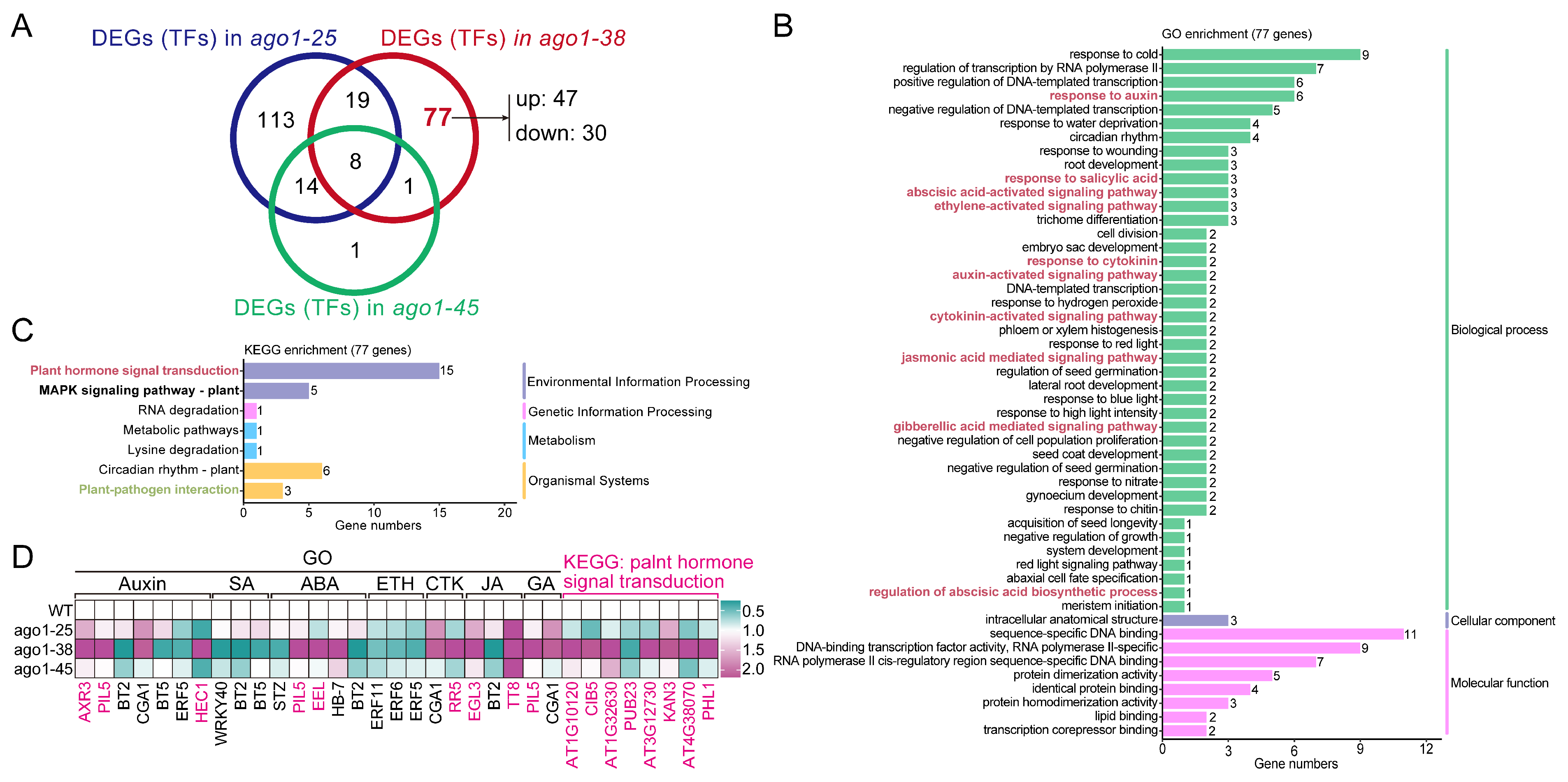

2.5. Expression of Differentially Expressed Transcription Factors in ago1-38

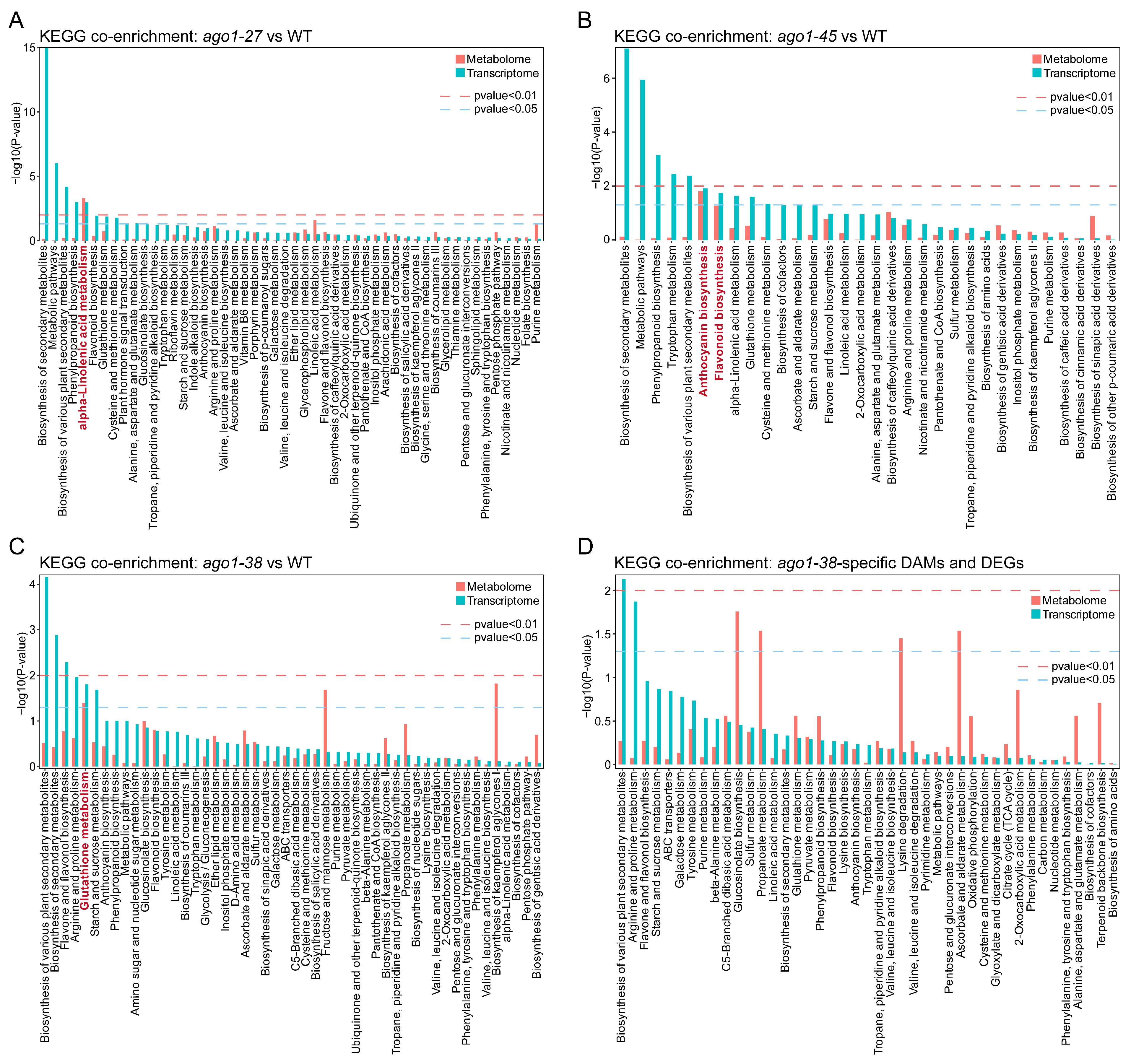

2.6. Integration of Transcriptome and Metabolome Profiles

3. Discussion

3.1. The Peculiar Phenotype of ago1-38

3.2. The Distinct Metabolic Profile of ago1-38

3.3. The Distinct Transcriptomic Profile of ago1-38

3.4. The Dysregulation of siRNA Processing Pathway in ago1-38

3.5. The Disturbed Plant–Pathogen Interaction Networks in ago1-38

3.6. The Disturbed Phytohormone Signaling Cascades in ago1-38

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Cultivation and Growth Conditions

4.2. Construction of ago1-38 Complementation Lines

4.3. Widely Targeted Metabolome Analysis

4.4. Transcriptome Analysis

4.5. Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| AGO1 | ARGONAUTE 1 |

| CTK | cytokinin |

| DA | differential abundance |

| DAMs | differentially accumulated metabolites |

| DCL | Dicer-like |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| dsRNAs | double-stranded RNAs |

| ETH | ethylene |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments |

| GA | gibberellic acid |

| HYL1 | hyponastic leaves 1 |

| JA | jasmonic acid |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| NRPB | nuclear DNA-dependent RNA polymerases II |

| NRPD | nuclear DNA-dependent RNA polymerases IV |

| NRPE | nuclear DNA-dependent RNA polymerases V |

| nt | nucleotide |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| Pol VI | RNA polymerase VI |

| Pol V | RNA polymerase V |

| Pol II | RNA polymerase II |

| RdDM | RNA directed DNA methylation |

| RDRs | RNA-dependent RNA polymerases |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| SA | salicylic acid |

| SAM | shoot apical meristem |

| SGSs | suppressor of gene silencing |

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| sRNAs | small RNAs |

| TFs | transcription factors |

| VIP | variable importance in projection |

| WGCNA | weighted correlation network analysis |

| WT | wild type |

References

- Su, L.Y.; Li, S.S.; Liu, H.; Cheng, Z.M.; Xiong, A.S. The origin, evolution, and functional divergence of the Dicer-like (DCL) and Argonaute (AGO) gene families in plants. Epigenet. Insights 2024, 17, e003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Castillo-González, C.; Yu, B.; Zhang, X. The functions of plant small RNAs in development and in stress responses. Plant J. 2017, 90, 654–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, J.; Meyers, B.C. Plant Small RNAs: Their Biogenesis, Regulatory Roles, and Functions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. Small RNAs and their roles in plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009, 25, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Su, H.; Xi, X.; Xu, X.; Qin, Y.; Cai, H. Advances in Small RNA Regulation of Female Gametophyte Development in Flowering Plants. Plants 2025, 14, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohmert, K. AGO1 defines a novel locus of Arabidopsis controlling leaf development. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, C.; Vaucheret, H.; Brodersen, P. Lessons on RNA Silencing Mechanisms in Plants from Eukaryotic Argonaute Structures. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Qi, Y. RNAi in plants: An argonaute-centered view. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xin, Y.; Xu, L.; Cai, Z.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xie, D.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Y. Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE 1 Binds Chromatin to Promote Gene Transcription in Response to Hormones and Stresses. Dev. Cell 2018, 44, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-González, C.; Zhang, X. Transactivator: A New Face of Arabidopsis AGO1. Dev. Cell 2018, 44, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagard, M.; Boutet, S.; Morel, J.-B.; Bellini, C.; Vaucheret, H. AGO1, QDE-2, and RDE-1 are related proteins required for posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants, quelling in fungi, and RNA interference in animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 11650–11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Pan, X.; Yuan, Z. Microbially mediated plant salt tolerance and microbiome-based solutions for saline agriculture. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrobel, O.; Ćavar Zeljković, S.; Dehner, J.; Spíchal, L.; De Diego, N.; Tarkowski, P. Multi-class plant hormone HILIC-MS/MS analysis coupled with high-throughput phenotyping to investigate plant–environment interactions. Plant J. 2024, 120, 818–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santner, A.; Calderon-Villalobos, L.I.A.; Estelle, M. Plant hormones are versatile chemical regulators of plant growth. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrahov, N.R.; Aghazada, G.A.; Alizada, S.R.; Mehdiyeva, G.V.; Mammadova, R.B.; Alizade, S.A.; Mammadov, Z.M. The involvement of phytohormones in plant–pathogen interaction. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2024, 15, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, N.O.; Spechenkova, N.A.; Taliansky, M.E. Biotechnological Approaches to Plant Antiviral Resistance: CRISPR-Cas or RNA Interference? Biochemistry 2025, 90, 804–817. [Google Scholar]

- Ansbacher, B.; Guzman, M.; Garcia-Ojalvo, J.; Pattanayak, A.K. Mapping gene expression dynamics to developmental phenotypes with information entropy analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.04101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.X.; Yang, S.J.; Yin, X.X.; Yan, X.L.; Hassan, B.; Fan, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.-M. Argonaute 1: A node coordinating plant disease resistance with growth and development. Phytopathol. Res. 2023, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressendorff, S.; Kausika, S.; Sjøgaard, I.M.Z.; Oksbjerg, E.D.; Michels, A.; Poulsen, C.; Brodersen, P. The N-coil and the globular N-terminal domain of plant ARGONAUTE1 are interaction hubs for regulatory factors. Biochem. J. 2023, 480, 957–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Merchán, A.; Lavatelli, A.; Engler, C.; González-Miguel, V.M.; Moro, B.; Rosano, G.L.; Bologna, N.G. Arabidopsis AGO1 N-terminal extension acts as an essential hub for PRMT5 interaction and post-translational modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 8466–8482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, B.D.; O’Malley, R.C.; Lister, R.; Urich, M.A.; Tonti-Filippini, J.; Chen, H.; Millar, A.H.; Ecker, J.R. A Link between RNA Metabolism and Silencing Affecting Arabidopsis Development. Dev. Cell 2008, 14, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, P.; Sakvarelidze-Achard, L.; Schaller, H.; Khafif, M.; Schott, G.; Bendahmane, A.; Voinnet, O. Isoprenoid biosynthesis is required for miRNA function and affects membrane association of ARGONAUTE 1 in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1778–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiehn, O.; Kopka, J.; Dörmann, P.; Altmann, T.; Trethewey, R.N.; Willmitzer, L. Metabolite profiling for plant functional genomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 1157–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Anas, M.; Bhardwaj, S.; Mir, R.A.; Charagh, S.; Elahi, M.; Zhang, X.; Mir, R.R.; Weckwerth, W.; Fernie, A.R.; et al. Harnessing metabolomics for enhanced crop drought tolerance. Crop J. 2025, 13, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Gu, C.; He, C.; Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J.; Zhao, H.; Niu, D. Bacillus cereus ar156 activates defense responses to pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato in arabidopsis thaliana similarly to flg22. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2018, 31, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Li, H.J.; Nie, J.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Lv, L.; Yang, Z.; Sui, X. Disruption of the amino acid transporter csaap2 inhibits auxin-mediated root development in cucumber. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Wu, X.; Fang, C.; Xu, Z.-G.; Zhang, H.-W.; Gao, J.; Zhou, C.-M.; You, L.-L.; Gu, Z.-X.; Mu, W.-H.; et al. Pol IV and RDR2: A two-RNA-polymerase machine that produces double-stranded RNA. Science 2021, 374, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.L.; Huang, K.; Deng, D.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. DNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases in Plants. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 3641–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.Y.; Wang, L.; Lei, Z.; Li, H.; Fan, W.; Cho, J. Ribosome stalling and SGS3 phase separation prime the epigenetic silencing of transposons. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, M.; Purkayastha, A.; Dasgupta, I. Silencing suppressor protein prt of rice tungro bacilliform virus interacts with the plant rna silencing-related protein sgs3. Virology 2023, 581, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Huang, H.; Lin, X.; Liu, P.; Zhao, L.; Nie, W.F.; Zhu, J.K.; Lang, Z. MSI4/FVE is required for accumulation of 24-nt siRNAs and DNA methylation at a subset of target regions of RNA-directed DNA methylation. Plant J. 2021, 108, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Song, Z.; Tang, K.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Ban, T.; Guo, Z.; Kim, C.; Zhang, H.; Duan, C.-G.; et al. A Histone H3K4me1-Specific Binding Protein Is Required for Sirna Accumulation and DNA Methylation at a Subset of Loci Targeted by RNA-Directed DNA Methylation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar-Agarwal, S.; Jin, H. Role of small rnas in host-microbe interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2010, 48, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Yan, J.; Xie, D. Comparison of phytohormone signaling mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Qing, X.; Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Mo, B.; Ren, Y. Integrative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis Provides New Insights into the Multifunctional ARGONAUTE 1 Through an Arabidopsis ago1-38 Mutant with Pleiotropic Growth Defects. Plants 2026, 15, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010044

Chen X, Qing X, Peng X, Xu X, Mo B, Ren Y. Integrative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis Provides New Insights into the Multifunctional ARGONAUTE 1 Through an Arabidopsis ago1-38 Mutant with Pleiotropic Growth Defects. Plants. 2026; 15(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiangze, Xinwen Qing, Xiaoli Peng, Xintong Xu, Beixin Mo, and Yongbing Ren. 2026. "Integrative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis Provides New Insights into the Multifunctional ARGONAUTE 1 Through an Arabidopsis ago1-38 Mutant with Pleiotropic Growth Defects" Plants 15, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010044

APA StyleChen, X., Qing, X., Peng, X., Xu, X., Mo, B., & Ren, Y. (2026). Integrative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis Provides New Insights into the Multifunctional ARGONAUTE 1 Through an Arabidopsis ago1-38 Mutant with Pleiotropic Growth Defects. Plants, 15(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010044