Evaluating the Suitability of Four Plant Functional Groups in Green Roofs Under Nitrogen Deposition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

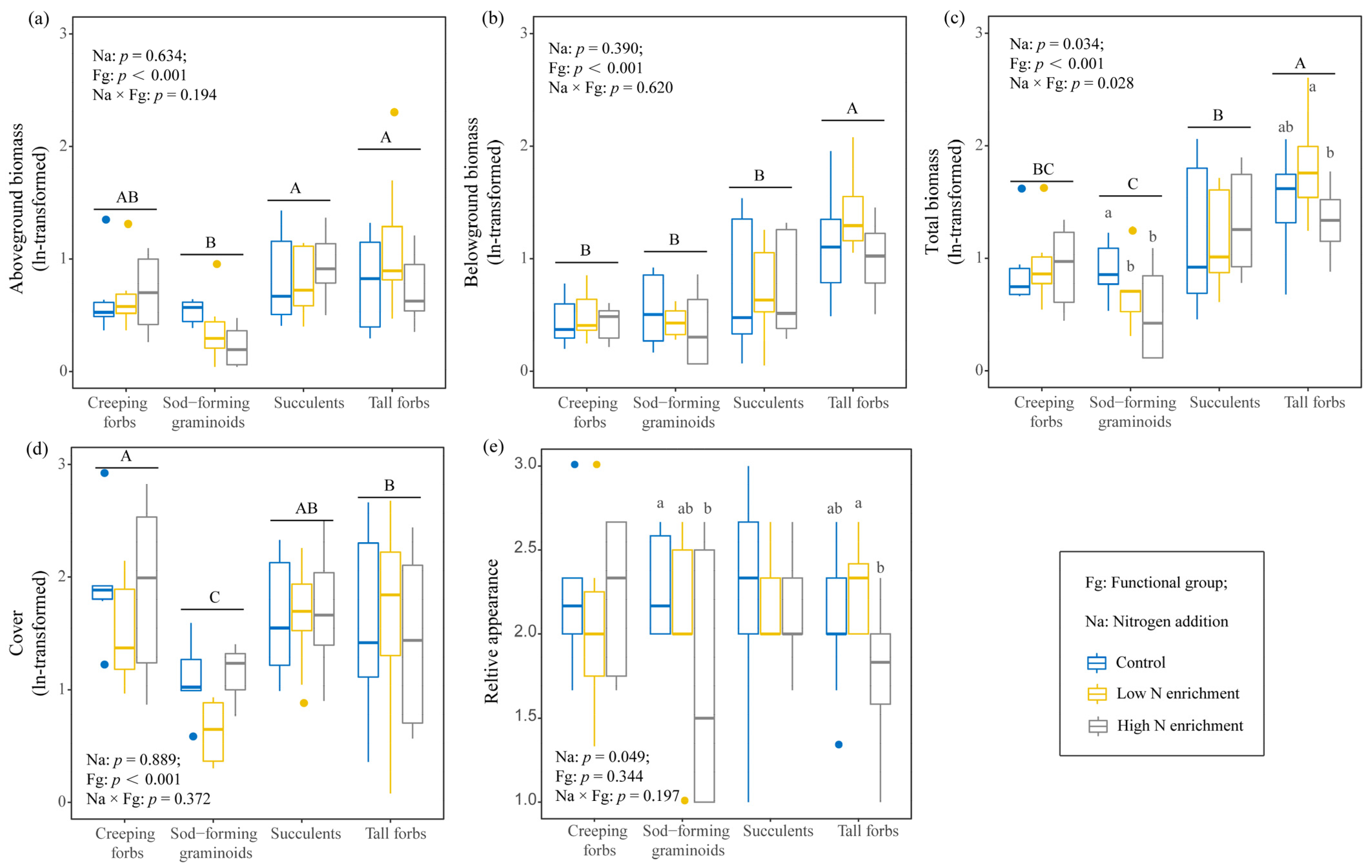

2.1. Effects of N Addition on Growth and Aesthetic Value of Four Functional Groups

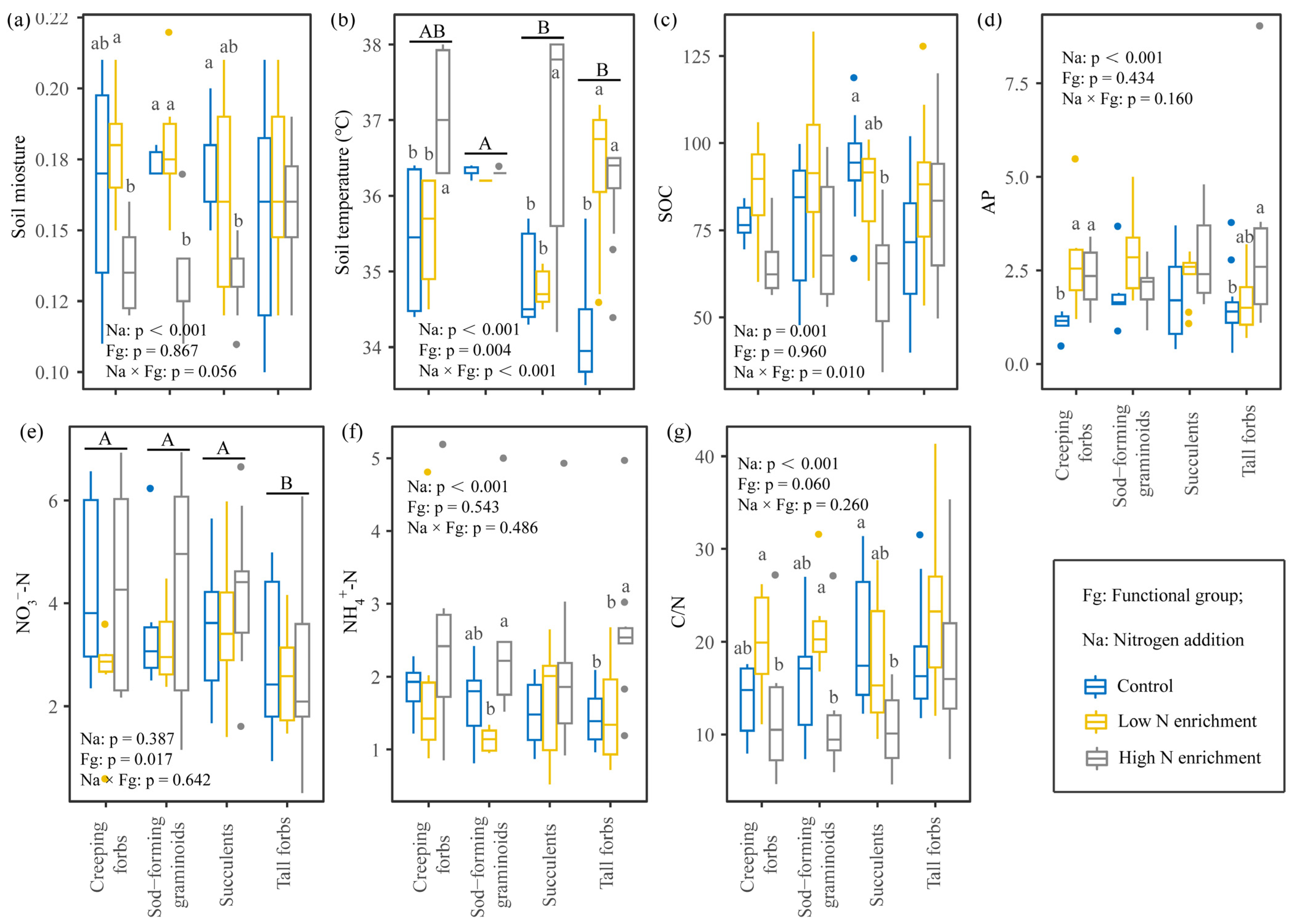

2.2. Effects of N Addition on Soil Properties of Four Functional Groups

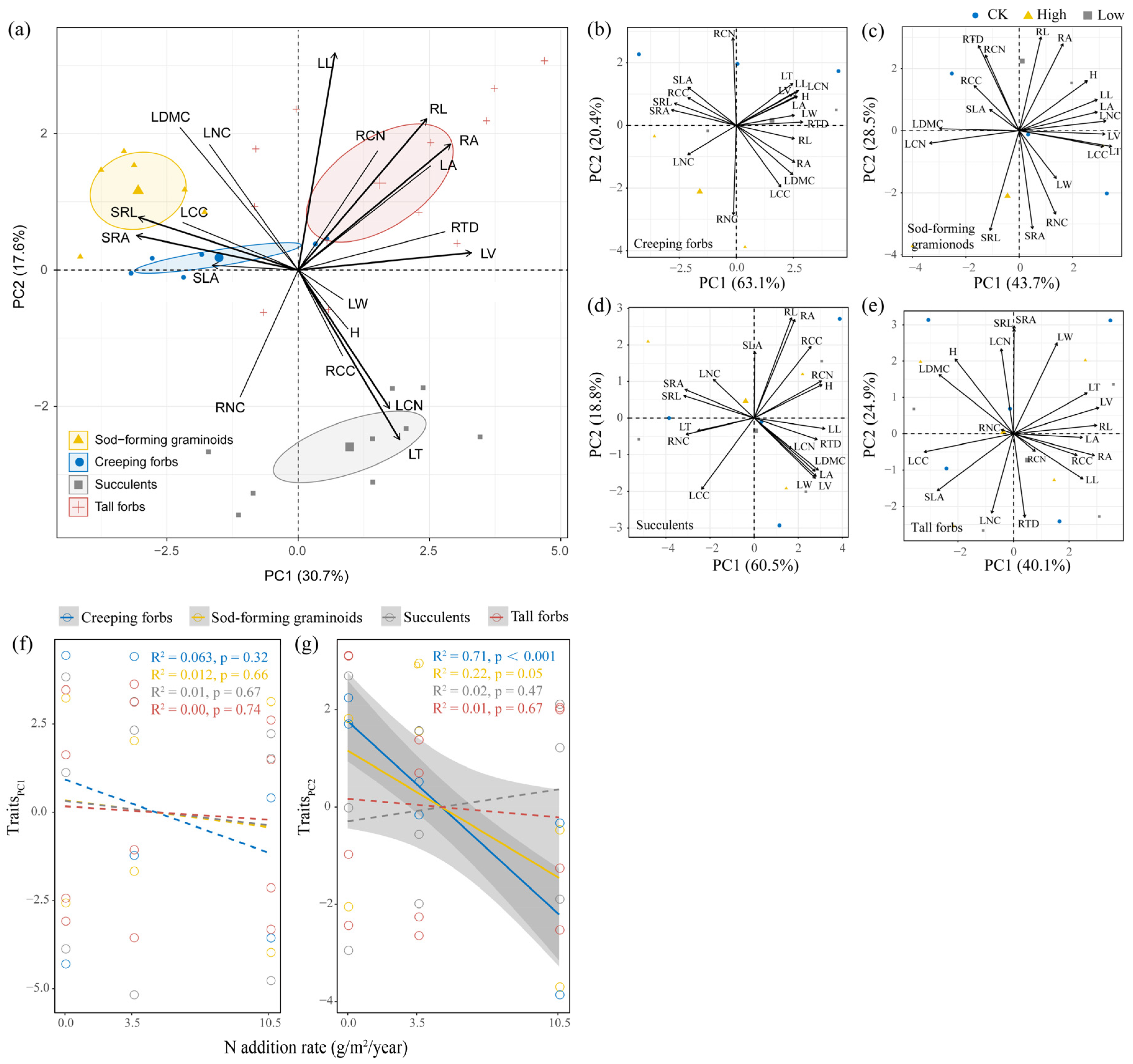

2.3. Effects of N Addition on Functional Traits of Four Functional Groups

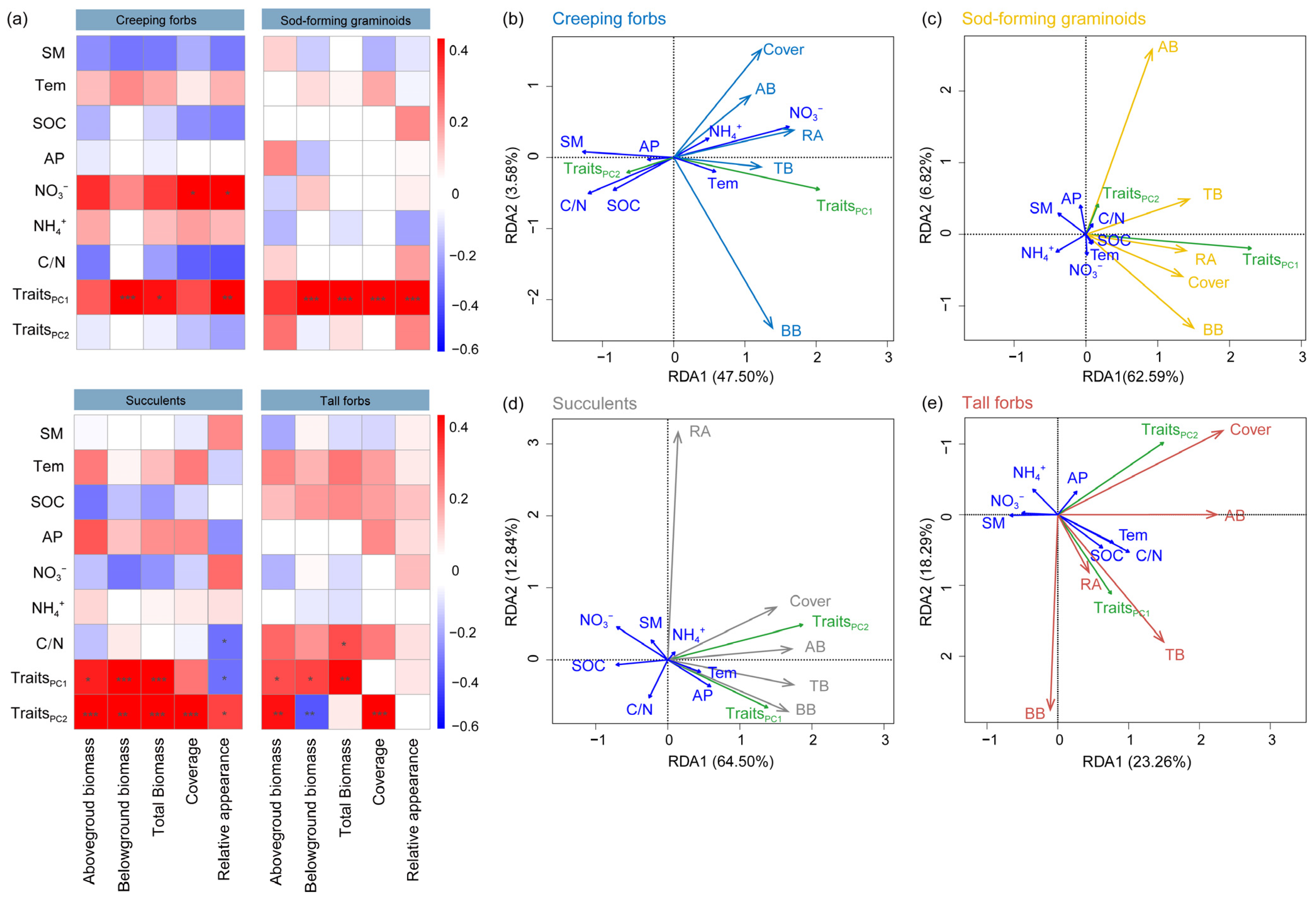

2.4. Relationships Between Growth Performance, Aesthetic Value, and Predictor Variables of Different Functional Groups

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Growth Measurements

4.4. Aesthetic Evaluation

4.5. Functional Trait Measurement

4.6. Soil Properties Measurement

4.7. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, N.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hao, G. Economy-society-ecology-humanistic values of green roofs and its contribution to sustainable development. South China Agr. 2023, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dunnett, N.; Nagase, A.; Hallam, A. The dynamics of planted and colonising species on a green roof over six growing seasons 2001–2006: Influence of substrate depth. Urban Ecosyst. 2008, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeñas, V.; Janner, I.; Medrano, H.; Gulías, J. Evaluating the establishment performance of six native perennial mediterranean species for use in extensive green roofs under water-limiting conditions. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, G.; Yang, N.; Chen, X.; Du, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, L.; Li, H. Nitrogen enrichment decrease green roof multifunctionality. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 93, 128233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleen, B.; Colin, M.O. Sedum cools soil and can improve neighboring plant performance during water deficit on a green roof. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 1796–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIvor, J.S.; Lundholm, J. Performance evaluation of native plants suited to extensive green roof conditions in a maritime climate. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, A.; Dunnett, N.P. Amount of water runoff from different vegetation types on extensive green roofs: Effects of plant species, diversity and plant structure. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 104, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, G.; Chen, X.; Du, Z.; Yang, N.; Li, M.; Gao, Y.; Liang, J.; Chen, L.; Li, H. Phylogenetic and functional diversity consistently increase engineered ecosystem functioning under nitrogen enrichment: The example of green roofs. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 212, 107499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getter, K.; Rowe, D. The role of extensive green roofs in sustainable development. HortScience 2006, 41, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksi, M.; Rowe, D.B. Effect of substrate depth and type on plant growth for extensive green roofs in a Mediterranean climate. J. Green Build. 2019, 14, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Jia, Y.; He, N.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Piao, S.; Liu, X.; He, H.; Guo, X.; et al. Stabilization of atmospheric nitrogen deposition in China over the past decade. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Liu, N.; Bai, W.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Reich, P.B.; Yu, Q.; Guo, D.; Smith, M.D.; Knapp, A.K.; et al. A novel soil manganese mechanism drives plant species loss with increased nitrogen deposition in a temperate steppe. Ecology 2016, 97, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Wu, F.; Gan, Y.; Yang, W.; Hu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Tan, B.; Liu, L.; Ni, X. Grass and forbs respond differently to nitrogen addition: A meta-analysis of global grassland ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2017, 8, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Dong, S.; Li, S.; Xiao, J.; Han, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Gao, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Effects of simulated N deposition on photosynthesis and productivity of key plants from different functional groups of alpine meadow on Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 251, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J.; Dise, N.B.; Gowing, D.J.G.; Mountford, O. Loss of forb diversity in relation to nitrogen deposition in the UK: Regional trends and potential controls. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shen, H.; Dong, S.; Li, S.; Xiao, J.; Zhi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, H.; Wu, S.; Mu, Z.; et al. Effects of 5-year nitrogen addition on species composition and diversity of an alpine steppe plant community on Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Plants 2022, 11, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Song, Z.; Wang, W.; Hu, G.; Qi, Z. Response of aboveground biomass and diversity to nitrogen addition along a degradation gradient in the Inner Mongolian steppe, China. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.J.; Zheng, Y. Effect of fertilizer rate on plant growth and leachate nutrient content during production of Sedum-vegetated green roof modules. HortScience 2014, 49, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusza, Y.; Barot, S.; Kraepiel, Y.; Lata, J.; Abbadie, L.; Raynaud, X. Multifunctionality is affected by interactions between green roof plant species, substrate depth, and substrate type. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 2357–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Arndt, S.; Miller, R.; Lu, N.; Farrell, C. Are succulence or trait combinations related to plant survival on hot and dry green roofs? Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenkäs, A.; Schumacher, J.; Roscher, C. Phenotypic plasticity to light and nutrient availability alters functional trait ranking across eight perennial grassland species. AoB Plants 2015, 27, plv029. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Y.; Tian, J.; Liu, L.; Han, L.; Wang, D. Coupling of different plant functional group, soil, and litter nutrients in a natural secondary mixed forest in the Qinling Mountains, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 66272–66286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, O.M. Succulent plant diversity as natural capital. Plants People Planet 2019, 1, 336–345. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Li, M.; Li, D.; Ali Khan, S.; Hepworth, S.R.; Wang, S. Transcriptome analysis reveals regulatory framework for salt and osmotic tolerance in a succulent xerophyte. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Liu, R.; Huang, G.; Wu, H.; Zhao, C. Effect of short-term nitrogen addition on productivity and plant diversity of subalpine grassland in Qilian Mountains. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 5034–5044. [Google Scholar]

- Lundholm, J.; Tran, S.; Gebert, L. Plant functional traits predict green roof ecosystem services. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B. The world-wide ‘fast-slow’ plant economics spectrum: A traits manifesto. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, F.; Cruz, P.; Jouany, C. Hierarchy of root functional trait values and plasticity drive early-stage competition for water and phosphorus among grasses. Funct. Ecol. 2014, 28, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craine, J.M.; Froehle, J.; Tilman, D.G.; Wedin, D.A.; Chapin, F.S. The relationships among root and leaf traits of 76 grassland species and relative abundance along fertility and disturbance gradients. Oikos 2001, 93, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuanes, A.O.; Kjonaas, O.J. Soil solution chemistry during four years of NH4NO3 addition to a forested catchment at Grdsjn, Sweden. For. Ecol. Manag. 1998, 101, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachiya, T.; Sakakibara, H. Interactions between nitrate and ammonium in their uptake, allocation, assimilation, and signaling in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2501–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Kronzucker, H.J.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Shi, W.; Li, Y. The role of the nitrate transporter NRT1.1 in plant iron homeostasis and toxicity on ammonium. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 232, 106112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hasi, M.; Li, A.; Tan, Y.; Daryanto, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Huang, J. Nitrogen addition amplified water effects on species composition shift and productivity increase. J. Plant Ecol. 2021, 14, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Bai, X.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Z.; Chen, R.; Niu, X. Physiological response of four wild Poa to soil pH. Pratacultural Sci. 2017, 34, 2445–2453. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, E.G.; Callahan, H.S.; Griffin, K.L.; Palmer, M.I.; Lee, S. Seasonal patterns of native plant cover and leaf trait variation on New York City green roofs. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 25, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.; Schweinhart, S.; Buffam, I. Plant species richness enhances nitrogen retention in green roof plots. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 2130–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Luo, J.; Tan, N.; Li, X.; Luo, H.; Zeng, F.; Liu, X.; Wu, T. Effects of drought stress on growth, nutrient content, and stoichiometry of four native tree species in South China. Chinese J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2024, 30, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Hao, G.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Kang, B.; Yang, N.; Li, H. Transformation of plant to resource acquisition under high nitrogen addition will reduce green roof ecosystem functioning. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 894782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundholm, J.; Heim, A.; Tran, S.; Smith, T. Leaf and life history traits predict plant growth in a green roof ecosystem. PLoS ONE 2014, 7109, e101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ren, G. Variation characteristics of sunshine duration in Tianjin in recent 40 years and influential factors. Meteorol. Sci. Technol. 2006, 34, 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Harguindeguy, N.; Díaz, S.; Garnier, E.; Lavorel, S.; Poorter, H.; Jaureguiberry, P.; Bret-Harte, M.S.; Cornwell, W.K.; Craine, J.; Gurvich, D.E.; et al. New handbook for standardised measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Aust. J. Bot. 2013, 61, 167–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis; Agricultural Publication: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lundholm, J.T.; MacIvor, J.S.; MacDougall, Z.; Ranalli, M.A. Plant species and functional group combinations affect green roof ecosystem functions. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, F.R.; Antunes, M.; Silva, D. Sustainable construction based on green roofs designed to retain rainwater and provide food: An LCA compared to conventional roofs. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2025, 59, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Tropical soil biology and fertility: A handbook of methods. Soil Sci. 1994, 157, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.A.; Bazzaz, F.A.; Minocha, R.; Long, S.; Magill, A.H.; Aber, J.D.; Berntson, G.M. Effects of chronic N additions on tissue chemistry, photosynthetic capacity, and carbon sequestration potential of a red pine (Pinus resinosa Ait.) stand in the NE United States. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2004, 196, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.P.; Chapin, F.S.; Klein, D.R. Carbon/nutrient balance of boreal plants in relation to vertebrate herbivory. Oikos 1983, 40, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.G.; Batu, N.; Xu, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.F. Measuring grassland vegetation cover using digital camera images. Acta Pratacult. Sin. 2014, 23, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Kong, D.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, Q.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Q.; Yin, H. Climate and soil nutrients differentially drive multidimensional fine root traits in ectomycorrhizal-dominated alpine coniferous forests. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 2544–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, E.; Cortez, J.; Billès, G.; Navas, M.L.; Roumet, C.; Debussche, M.; Laurent, G.; Blanchard, A.; Aubry, D.; Bellmann, A.; et al. Plant functional markers capture ecosystem properties during secondary succession. Ecology 2004, 85, 2630–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Niu, S.; Yu, G. Aggravated phosphorus limitation on biomass production under increasing nitrogen loading: A meta-analysis. Global Change Biol. 2016, 222, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.K. Agriculture Chemical Analysis Methods of Soil; Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Maire, V.; Gross, N.; Börger, L.; Proulx, R.; Wirth, C.; Pontes, L.D.; Soussana, J.; Louault, F. Habitat filtering and niche differentiation jointly explain species relative abundance within grassland communities along fertility and disturbance gradients. New Phytol. 2012, 1962, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadelhoffer, K.J.; Emmett, B.A.; Gundersen, P.; Kjønaas, O.J.; Koopmans, C.J.; Schleppi, P.; Tietema, A.; Wright, R. Nitrogen deposition makes a minor contribution to carbon sequestration in temperate forests. Nature 1999, 398, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, J.C.; Van Bodegom, P.M.; Witte, J.P.M.; Wright, I.J.; Reich, P.B.; Aerts, R. A global study of relationships between leaf traits, climate and soil measures of nutrient fertility. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009, 18, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, D.B.; Getter, K.L.; Durhman, A.K. Effect of green roof media depth on Crassulacean plant succession over seven years. Landscape Urban Plan. 2012, 104, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, Y. Comparison of FIA and UV methods in determining soil nitrate nitrogen. J. Hebei Agr. Sci. 2016, 20, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.W.; Gan, Y.; Wu, Y. Biomass Allocation, Compensatory Growth and Internal C/N Balance of Lolium perenne in Response to Defoliation and Light Treatments. Pol. J. Ecol. 2016, 64, 485–499. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.B. A review of evidence on the control of shoot: Root ratio. Ann. Bot. 1988, 61, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Fang, J.Y.; Ji, C.J.; Han, W.X. Above- and belowground biomass allocation in Tibetan grasslands. J. Veg. Sci. 2009, 20, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Yan, S.; Wang, J.; Ma, C.; Gong, Z.; Dong, S.; Zhang, Q. Effect of returning rice straw into the field on soil phosphatase activity and available phosphorus content. Crop J. 2015, 000, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Family | Natural Habitat | Functional Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duchesnea indica | Rosaceae | Under the hillside forest | Creeping forbs |

| Potentilla reptans | Rosaceae | Hillside grassland and forest edge | Creeping forbs |

| Carex duriuscula | Cyperaceae | Semiarid grassland | Sod-forming graminoids |

| Buchloe dactyloides | Poaceae | Dry grasslands | Sod-forming graminoids |

| Sedum lineare | Crassulaceae | Rock crevices and hillside | Succulents |

| Phedimus aizoon | Crassulaceae | Hillside rocks and wasteland | Succulents |

| Hylotelephium erythrostictum | Crassulaceae | Hillside grassland, ditch edge, rock crevices | Succulents |

| Hemerocallis fulva | Asphodelaceae | Widespread habitat | Tall forbs |

| Coreopsis basalis | Asteraceae | Poor soils and sparse woods | Tall forbs |

| Physostegia virginiana | Lamiaceae | Sandy soil | Tall forbs |

| Iris tectorum | Iridaceae | Widespread habitat | Tall forbs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, N.; Li, H.; Wu, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Hao, G. Evaluating the Suitability of Four Plant Functional Groups in Green Roofs Under Nitrogen Deposition. Plants 2026, 15, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010043

Yang N, Li H, Wu R, Wang Y, Li M, Chen L, Li H, Hao G. Evaluating the Suitability of Four Plant Functional Groups in Green Roofs Under Nitrogen Deposition. Plants. 2026; 15(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Nan, Hechen Li, Runze Wu, Yihan Wang, Meiyang Li, Lei Chen, Hongyuan Li, and Guang Hao. 2026. "Evaluating the Suitability of Four Plant Functional Groups in Green Roofs Under Nitrogen Deposition" Plants 15, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010043

APA StyleYang, N., Li, H., Wu, R., Wang, Y., Li, M., Chen, L., Li, H., & Hao, G. (2026). Evaluating the Suitability of Four Plant Functional Groups in Green Roofs Under Nitrogen Deposition. Plants, 15(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010043