Genome-Wide Analysis of Cellulose Synthase Superfamily and Roles of GmCESA1 in Regulating Drought Tolerance and Growth of Soybean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

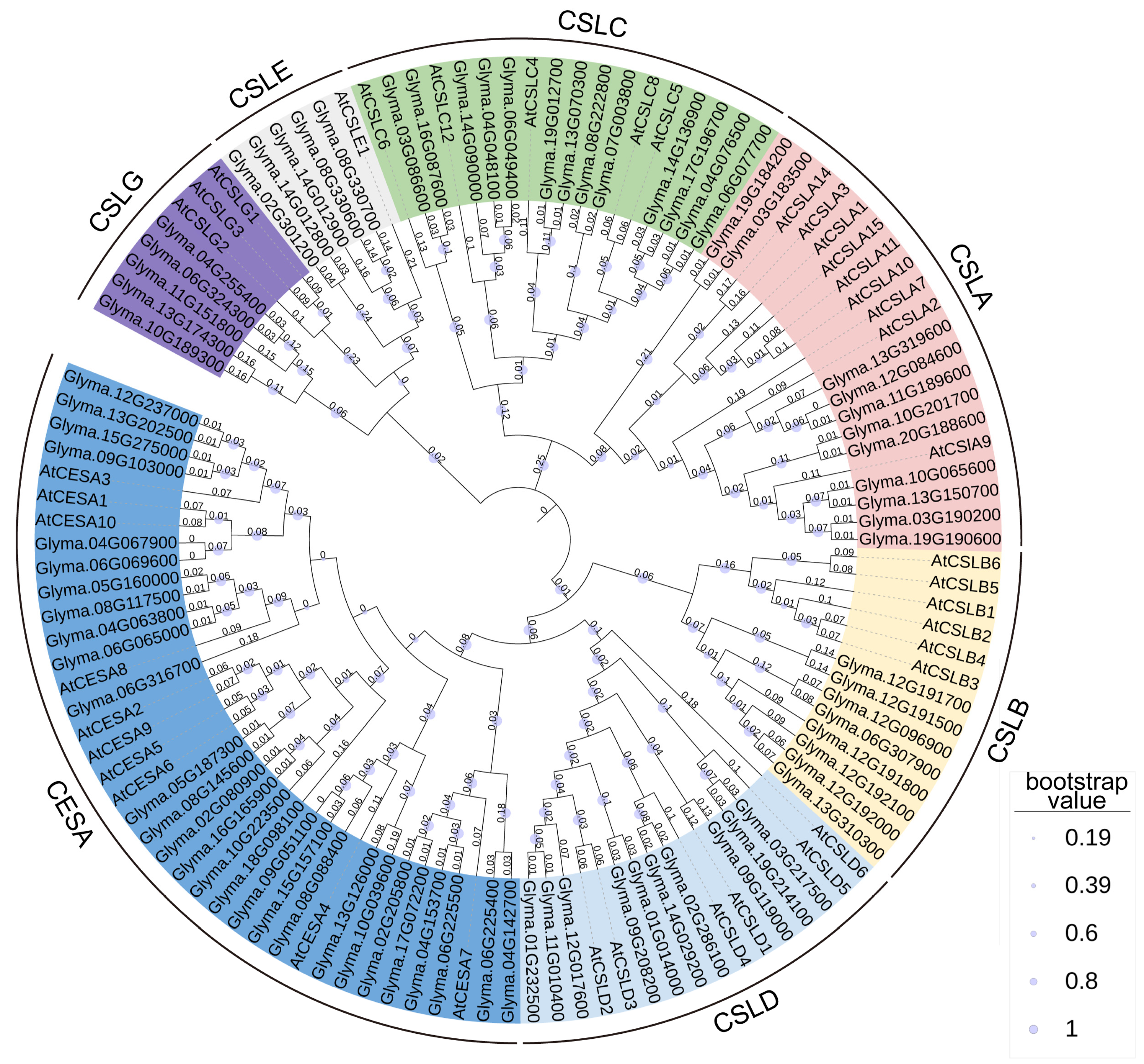

2.1. Identification and Phylogenetic Analyses of the CS Superfamily in Soybean

2.2. Gene Structures and Conserved Motifs of the Soybean CS Superfamily

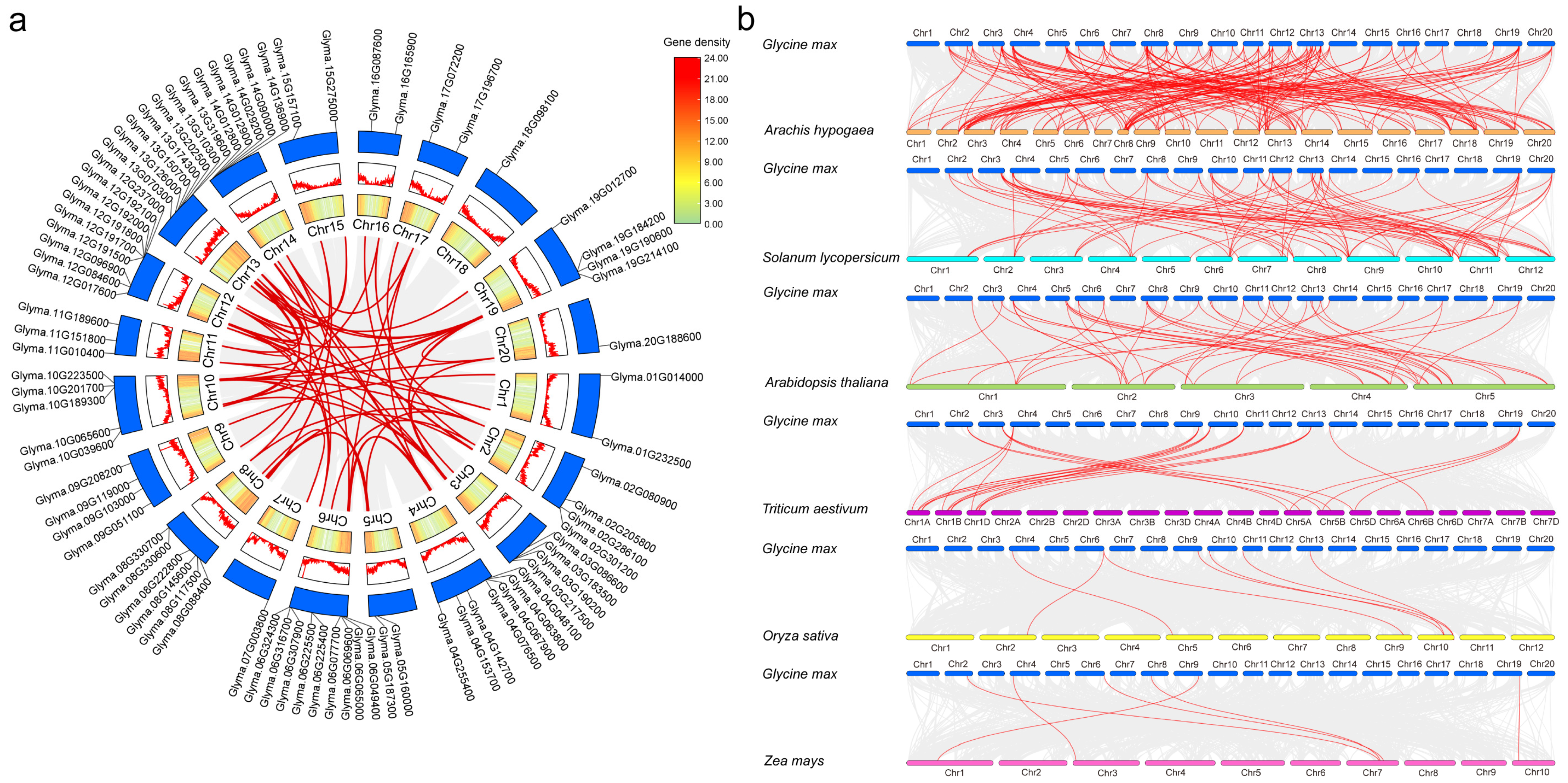

2.3. Intraspecific and Interspecific Collinearity of CS Genes

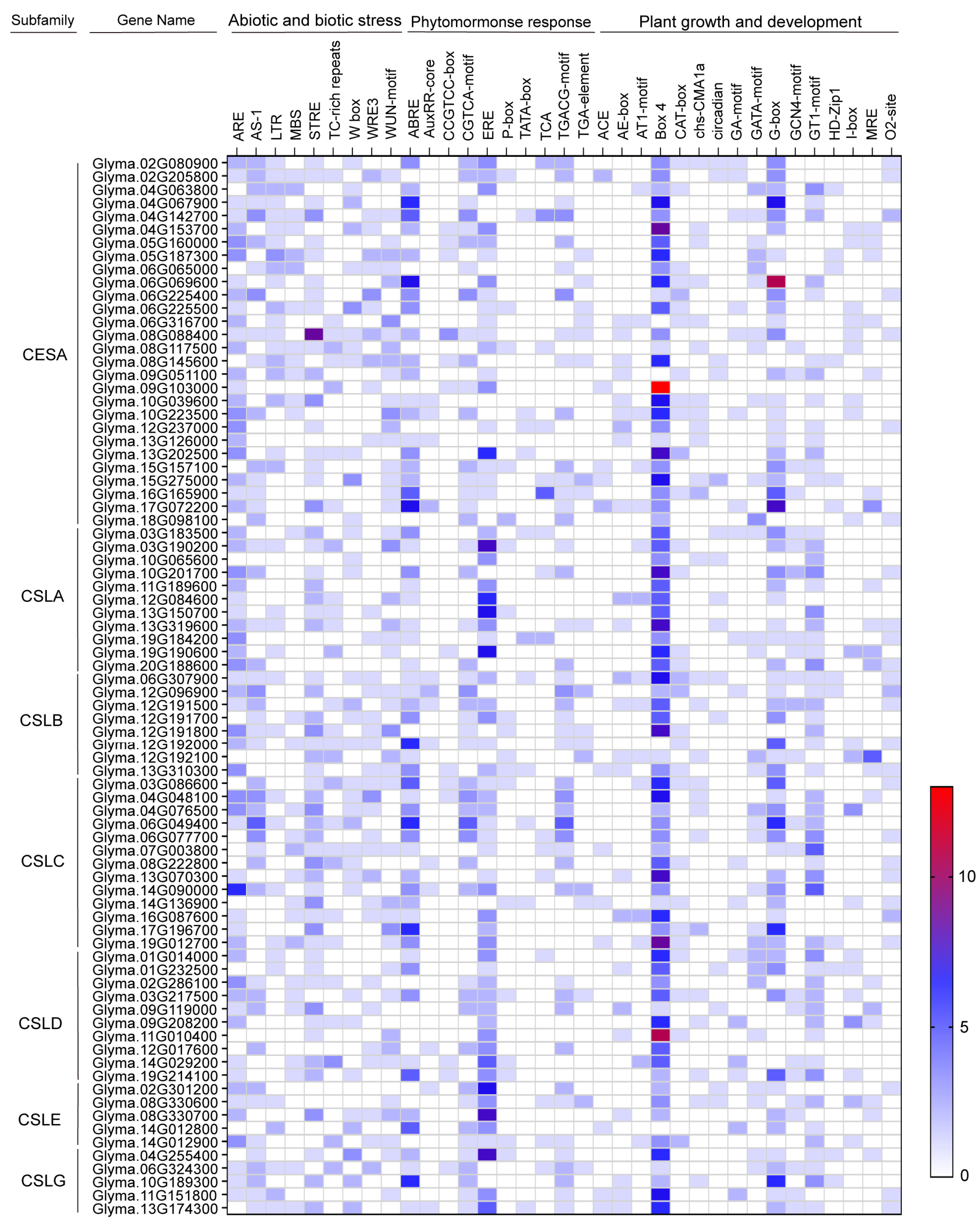

2.4. Cis-Acting Elements in CS Gene Promoters

2.5. Expression Patterns of CS Genes in Different Soybean Tissues

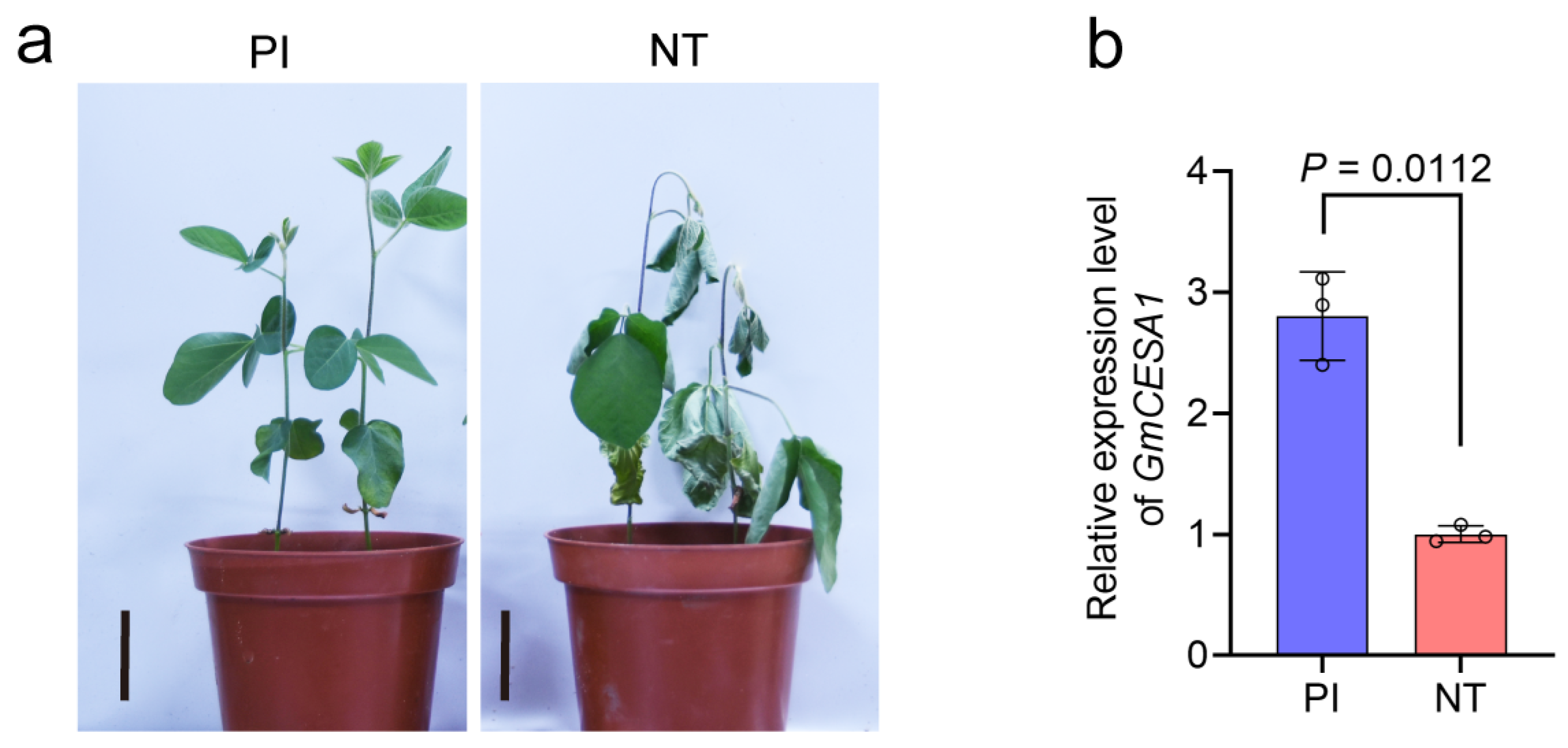

2.6. GmCESA1 Exhibited Higher Expression Level in the Drought-Tolerant Soybean Accession PI

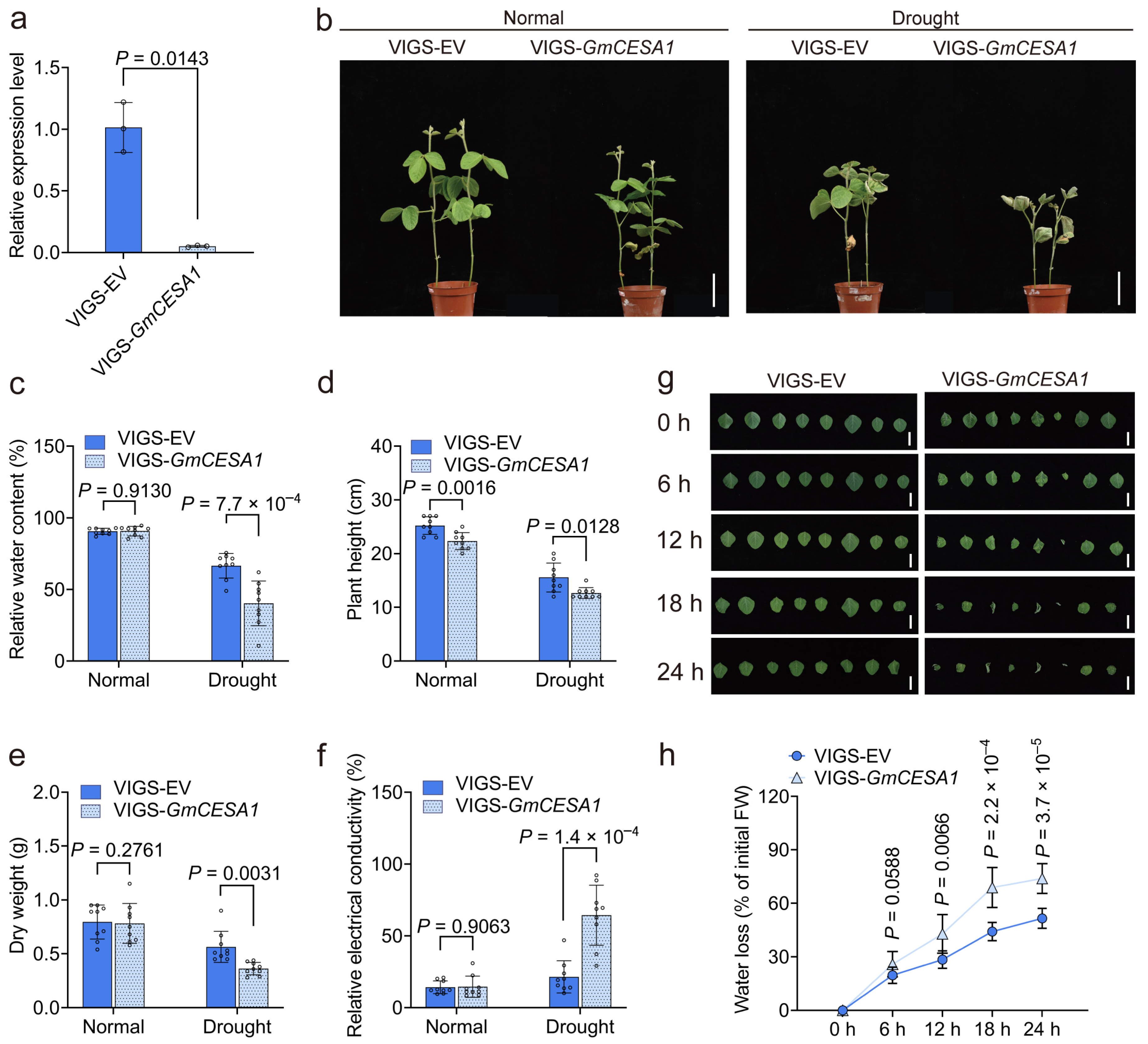

2.7. GmCESA1 Modulates Drought Tolerance and Growth of Soybean

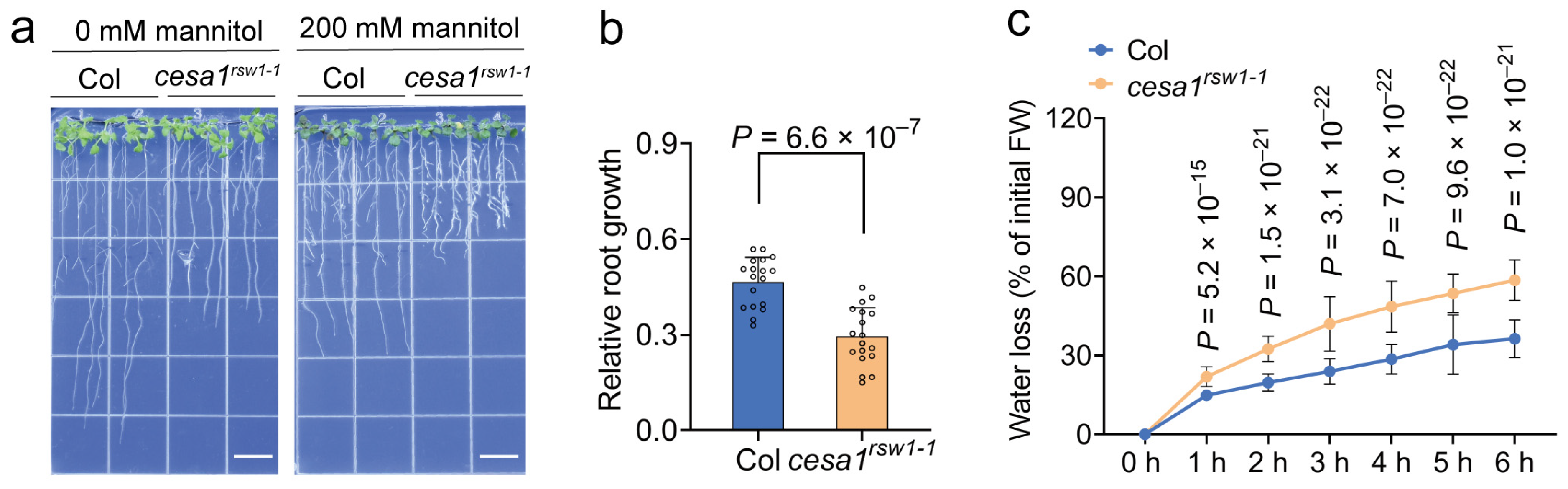

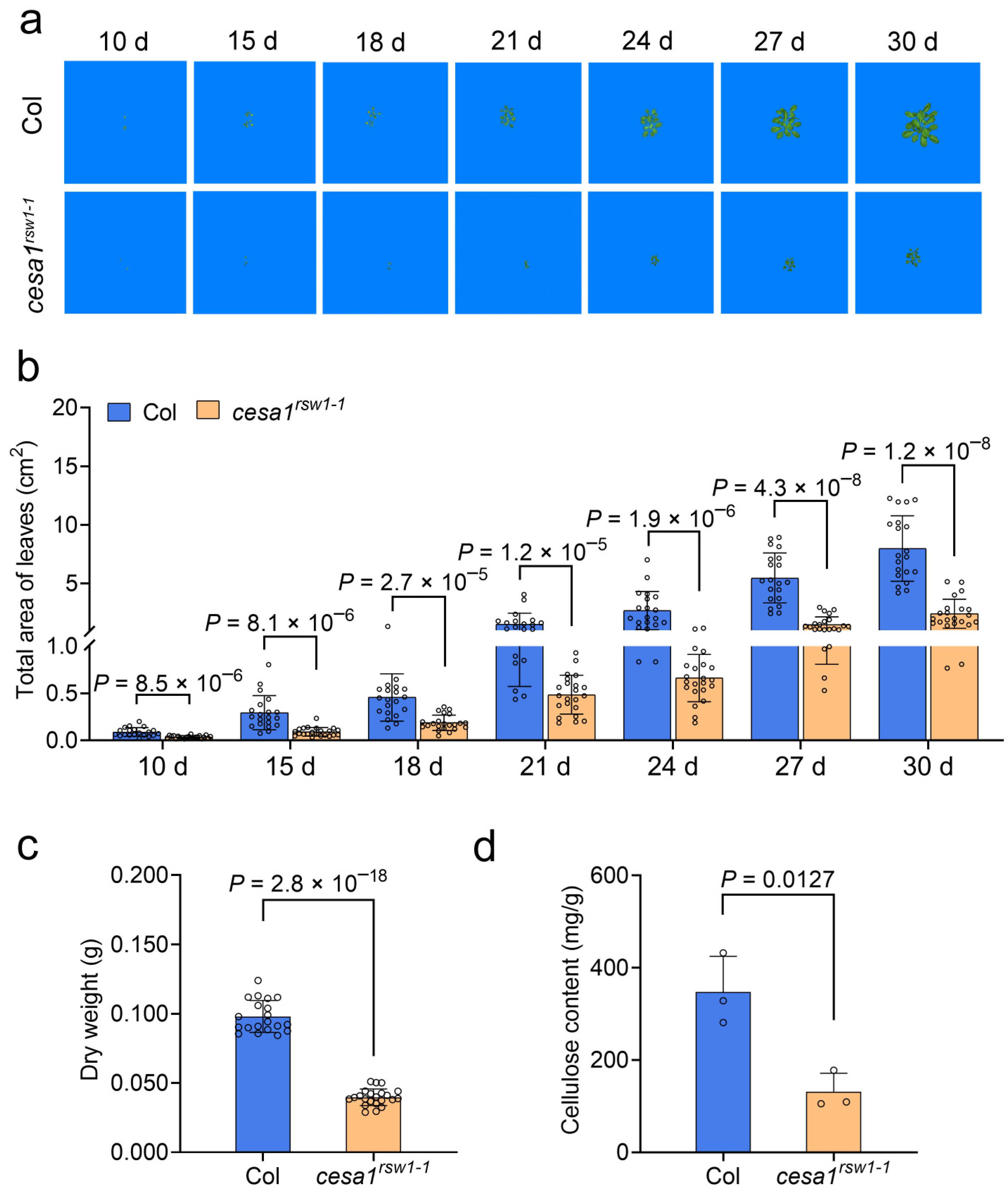

2.8. The Arabidopsis cesa1rsw1-1 Mutant Is Hypersensitive to Drought and Exhibits Impaired Growth

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of Soybean CS Genes

4.2. Gene Structure Analysis and Conserved Domain Detection of CS

4.3. Collinearity Analysis and Ka/Ks Calculation of CS Genes

4.4. Expression Analysis of CS Genes in Different Soybean Tissues

4.5. Promoter Cis-Acting Element Analysis

4.6. Plasmid Construction and Silencing of GmCESA1 in Soybean Plants

4.7. RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Analysis

4.8. Drought Treatment of Soybean and Determination of Physiological Indices

4.9. Measurement of Water Loss

4.10. Drought Treatment of Arabidopsis thaliana

4.11. Measurement of Arabidopsis thaliana Rosette Area and Biomass

4.12. Measurement of Cellulose Content

4.13. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPMV | Bean pod mottle virus |

| CS | Cellulose synthase |

| CSL | Cellulose synthase-like |

| DS | Drought-stress |

| REC | Relative electrical conductivity |

| RWC | Relative water content |

| NT | Nan tong xiao yuan dou |

| PI | PI595843 |

| VIGS | Virus-induced gene silencing |

References

- Tran, L.-S.P.; Mochida, K. Functional genomics of soybean for improvement of productivity in adverse conditions. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2010, 10, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manavalan, L.P.; Guttikonda, S.K.; Phan Tran, L.S.; Nguyen, H.T. Physiological and molecular approaches to improve drought resistance in soybean. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 1260–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, N.P.; Tran, L.-S.P. Potentials toward genetic engineering of drought-tolerant soybean. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2011, 32, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.Y.; Pence, H.E.; Jin, J.B.; Miura, K.; Gosney, M.J.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Mickelbart, M.V. The Arabidopsis GTL1 transcription factor regulates water use efficiency and drought tolerance by modulating stomatal density via transrepression of SDD1. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 4128–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.K. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002, 53, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, S.A.M.; Brodribb, T.J. Mesophyll cells are the main site of abscisic acid biosynthesis in water-stressed leaves. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalladan, R.; Lasky, J.R.; Chang, T.Z.; Sharma, S.; Juenger, T.E.; Verslues, P.E. Natural variation identifies genes affecting drought-induced abscisic acid accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11536–11541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, A.; de Zelicourt, A.; Colcombet, J.; Hirt, H. The role of ABA and MAPK signaling pathways in plant abiotic stress responses. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra, R.; Bhalothia, P.; Bansal, P.; Basantani, M.K.; Bharti, V.; Mehrotra, S. Abscisic acid and abiotic stress tolerance—Different tiers of regulation. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudsocq, M.; Barbier-Brygoo, H.; Lauriere, C. Identification of nine sucrose nonfermenting 1-related protein kinases 2 activated by hyperosmotic and saline stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 41758–41766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jammes, F.; Song, C.; Shin, D.; Munemasa, S.; Takeda, K.; Gu, D.; Cho, D.; Lee, S.; Giordo, R.; Sritubtim, S.; et al. MAP kinases MPK9 and MPK12 are preferentially expressed in guard cells and positively regulate ROS-mediated ABA signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20520–20525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.H.C.d. Drought stress and reactive oxygen species:Production, scavenging and signaling. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, C.; Wang, B.; Yang, S.; Guo, Y.; Gong, Z. Protein kinases in plant responses to drought, salt, and cold stress. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, G.J.; Blaukopf, C. Irritable walls: The plant extracellular matrix and signaling. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gall, H.; Philippe, F.; Domon, J.-M.; Gillet, F.; Pelloux, J.; Rayon, C. Cell wall metabolism in response to abiotic stress. Plants 2015, 4, 112–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrein, B.; Hamant, O. How mechanical stress controls microtubule behavior and morphogenesis in plants: History, experiments and revisited theories. Plant J. 2013, 75, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A.; Schwerdt, J.G.; Shirley, N.J.; Khor, S.F.; Neumann, K.; O’Donovan, L.A.; Lahnstein, J.; Collins, H.M.; Henderson, M.; Fincher, G.B.; et al. Revised phylogeny of the Cellulose synthase gene superfamily: Insights into cell wall evolution. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 1124–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.N.; Thomas, L.H.; Altaner, C.M.; Callow, P.; Forsyth, V.T.; Apperley, D.C.; Kennedy, C.J.; Jarvis, M.C. Nanostructure of cellulose microfibrils in spruce wood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, N.G. Cellulose biosynthesis and deposition in higher plants. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, A.; Kesten, C.; Schneider, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ivakov, A.; Froehlich, A.; Funke, N.; Persson, S. A mechanism for sustained cellulose synthesis during salt stress. Cell 2015, 162, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, C. Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006, 22, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, I.M.; Brown, R.M., Jr.; Fevre, M.; Geremia, R.A.; Henrissat, B. Multidomain architecture of β-glycosyl transferases: Implications for mechanism of action. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 1419–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pear, J.R.; Kawagoe, Y.; Schreckengost, W.E.; Delmer, D.P.; Stalker, D.M. Higher plants contain homologs of the bacterial celA genes encoding the catalytic subunit of cellulose synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 12637–12642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, N.; Holland, D.; Helentjaris, T.; Dhugga, K.S.; Xoconostle-Cazares, B.; Delmer, D.P. A comparative analysis of the plant cellulose synthase (CesA) gene family. Plant Physiol. 2000, 123, 1313–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, T.A.; Somerville, C.R. The cellulose synthase superfamily. Plant Physiol. 2000, 24, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao-Delgado, A.; Penfied, S.; Smith, C.; Catley, M. Reduced cellulose synthesis invokes lignification and defense responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2002, 34, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagard, M.; Desnos, T.; Desprez, T.; Goubet, F.; Refregier, G.; Mouille, G.; McCann, M.; Rayon, C.; Vernhettes, S.; Höfte, H. Procuste1 encodes a cellulose synthase required for normal cell elongation specifically in roots and dark-grown hypocotyls of arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 2409–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.G.; Howells, R.M.; Huttly, A.K.; Vickers, K.; Turner, S.R. Interactions among three distinct CesA proteins essential for cellulose synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1450–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desprez, T.; Juraniec, M.; Crowell, E.F.; Jouy, H.l.n.; Pochylova, Z.; Parcy, F.; Höfte, H.; Gonneau, M.; Vernhettes, S. Organization of cellulose synthase complexes involved in primary cell wall synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15572–15577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepman, A.H.; Wilkerson, C.G.; Keegstra, K. Expression of cellulose synthase-like (Csl) genes in insect cells reveals that CslA family members encode mannan synthases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 2221–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocuron, J.-C.; Lerouxel, O.; Drakakaki, G.; Alonso, A.P.; Liepman, A.H.; Keegstra, K.; Raikhel, N.; Wilkerson, C.G. A gene from the cellulose synthase-like C family encodes a β-1,4 glucan synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8850–8855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Verhertbruggen, Y.; Oikawa, A.; Manisseri, C.; Knierim, B.; Prak, L.; Jensen, J.K.g.; Knox, J.P.; Auer, M.; Willats, W.G.T.; et al. The cooperative activities of CSLD2, CSLD3, and CSLD5 are required for normal Arabidopsis development. Mol. Plant 2011, 4, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.A.; Wilson, S.M.; Hrmova, M.; Harvey, A.J.; Shirley, N.J.; Medhurst, A.; Stone, B.A.; Newbigin, E.J.; Bacic, A.; Fincher, G.B. Cellulose synthase-like CslF genes mediate the synthesis of cell wall (1,3;1,4)-β-D-glucans. Science 2006, 311, 1940–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblin, M.S.; Pettolino, F.A.; Wilson, S.M.; Campbell, R.; Burton, R.A.; Fincher, G.B.; Newbigin, E.; Bacic, A. A barley cellulose synthase-like CSLH gene mediates (1,3;1,4)-β-D-glucan synthesis in transgenic Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5996–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Frank, J.; Kang, C.H.; Kajiura, H.; Vikram, M.; Ueda, A.; Kim, S.; Bahk, J.D.; Triplett, B.; Fujiyama, K.; et al. Salt tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana requires maturation of N-glycosylated proteins in the Golgi apparatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5933–5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S.; Sun, L.; Dong, X.; Lu, S.J.; Tian, W.; Liu, J.X. Cellulose synthesis genes CESA6 and CSI1 are important for salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2016, 58, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Hong, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.K.; Gong, Z. Disruption of the cellulose synthase gene, AtCesA8/IRX1, enhances drought and osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005, 43, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Zeng, S.; Wu, K.; Yu, Z.; Wang, X.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Lin, Z.; Duan, J. Identification of genes involved in biosynthesis of mannan polysaccharides in Dendrobium officinale by RNA-seq analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015, 88, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X.; Gao, D.; Li, X. Physiological, cytological and multi-omics analysis revealed the molecular response of Fritillaria cirrhosa to Cd toxicity in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 472, 134611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Luo, S.; Chen, Z.; Yang, R.; He, X.; Chu, H.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Shi, Y. Genome-wide analysis of the Amorphophallus konjac AkCSLA gene family and its functional characterization in drought tolerance of transgenic arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lee, B.H.; Dellinger, M.; Cui, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, S.; Nothnagel, E.A.; Zhu, J.K. A cellulose synthase-like protein is required for osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010, 63, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, S.; Paredez, A.; Carrol, A.; Palsdottir, H.; Doblin, M.; Poindexter, P.; Khitrov, N.; Auer, M.; Somerville, C.R. Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15566–15571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Lu, Z.; Xue, C.; Jiang, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, G.; Zhong, F.; Zhang, J.; Lian, B. Comprehensive analysis of the LTPG gene family in willow: Identification, expression profiling, and stress response. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 295, 139600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garreton, V.; Carpinelli, J.; Jordana, X.; Holuigue, L. The as-1 promoter element is an oxidative stress-responsive element and salicylic acid activates it via oxidative species. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; Cui, W.; Wu, Y.; Yan, C.; Liu, H.; et al. The peroxidase gene OsPrx114 activated by OsWRKY50 enhances drought tolerance through ROS scavenging in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 204, 108138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Xie, H.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Nie, Y.; Chen, H.; Xie, X.; Tang, M. A module centered on the transcription factor Msn2 from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis regulates drought stress tolerance in the host plant. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 1497–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, L.; Ji, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, S. The specific W-boxes of GAPC5 promoter bound by TaWRKY are involved in drought stress response in wheat. Plant Sci. 2020, 296, 110460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, H.E.; Doring, A.; Persson, S. The cell biology of cellulose synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, M.; Liu, H.; Quan, R.; Zhang, H.; Huang, R.; Zhu, L.; et al. Cellulose synthase-like protein OsCSLD4 plays an important role in the response of rice to salt stress by mediating abscisic acid biosynthesis to regulate osmotic stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 20, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, R.; Feng, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Schneider, R.; Xia, T.; et al. Three AtCesA6-like members enhance biomass production by distinctively promoting cell growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 16, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszar, J.; Galle, A.; Horvath, E.; Dancso, P.; Gombos, M.; Vary, Z.; Erdei, L.; Gyorgyey, J.; Tari, I. Different peroxidase activities and expression of abiotic stress-related peroxidases in apical root segments of wheat genotypes with different drought stress tolerance under osmotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 52, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenhaken, R. Cell wall remodeling under abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucci, M.R.; Lenucci, M.S.; Piro, G.; Dalessandro, G. Water stress and cell wall polysaccharides in the apical root zone of wheat cultivars varying in drought tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, K.; Masuda, A.; Kuwano, M.; Yokota, A.; Akashi, K. Programmed proteome response for drought avoidance/tolerance in the root of a C3 xerophyte (wild watermelon) under water deficits. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, B.; Wang, X.; Li, M.H. Drought induces opposite changes in organ carbon and soil organic carbon to increase resistance on moso bamboo. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1474671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, J.C.; Bonine, C.A.; de Oliveira Fernandes Viana, J.; Dornelas, M.C.; Mazzafera, P. Abiotic and biotic stresses and changes in the lignin content and composition in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010, 52, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Meng, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B. Protein expression changes during cotton fiber elongation in response to drought stress and recovery. Proteomics 2014, 14, 1776–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Xiong, H.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Ma, S.; Duan, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Natural variation of DROT1 confers drought adaptation in upland rice. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, P.X.; Xu, P.; Yu, G.H.; Zhang, L.Y.; Xiong, Y.; Xiang, C.B. AtEDT1/HDG11 regulates stomatal density and water-use efficiency via ERECTA and E2Fa. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, S.L.; Lin, Q.F.; Feng, X.J.; Han, H.L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Le, J.; Blumwald, E.; Hua, X.J. IDD16 negatively regulates stomatal initiation via trans-repression of SPCH in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1446–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Peszlen, I.; Shi, R.; Kim, H.; Katahira, R.; Kafle, K.; Xiang, Z.; Huang, X.; Min, D.; Mohamadamin, M.; et al. Involvement of CesA4, CesA7-A/B and CesA8-A/B in secondary wall formation in Populus trichocarpa wood. Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.Z.; Chen, S.; Qi, X.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Deng, Y. Identification of Nramp gene family in Hydrangea macrophylla and characterization of HmNramp5 under aluminum stress condition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 144796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Bradshaw, J.D.; Whitham, S.A.; Hill, J.H. The development of an efficient multipurpose bean pod mottle virus viral vector set for foreign gene expression and RNA silencing. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Su, C.; Tang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Chen, M.; Ma, Y. Nuclear transport factor GmNTF2B-1 enhances soybean drought tolerance by interacting with oxidoreductase GmOXR17 to reduce reactive oxygen species content. Plant J. 2021, 107, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flexas, J.; Ribas-Carbó, M.; Bota, J.; Galmés, J.; Henkle, M.; Martínez-Cañellas, S.; Medrano, H. Decreased Rubisco activity during water stress is not induced by decreased relative water content but related to conditions of low stomatal conductance and chloroplast CO2 concentration. New Phytol. 2006, 172, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.Q.; Song, L.L.; Jacobs, D.F.; Mei, L.; Liu, P.; Jin, S.H.; Wu, J.S. Physiological response to drought stress in Camptotheca acuminata seedlings from two provenances. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arioli, T.; Peng, L.; Betzner, A.S.; Burn, J.; Wittke, W.; Herth, W.; Camilleri, C.; Höfte, H.; Plazinski, J.; Birch, R.; et al. Molecular analysis of cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Science 1998, 279, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, C.; Chen, J.; He, J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, S.; Pan, Y.; Jin, T.; Li, Y. Genome-Wide Analysis of Cellulose Synthase Superfamily and Roles of GmCESA1 in Regulating Drought Tolerance and Growth of Soybean. Plants 2026, 15, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010034

Wu C, Chen J, He J, Zhang X, Zheng S, Pan Y, Jin T, Li Y. Genome-Wide Analysis of Cellulose Synthase Superfamily and Roles of GmCESA1 in Regulating Drought Tolerance and Growth of Soybean. Plants. 2026; 15(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Chunhua, Jie Chen, Jiazhou He, Xiujie Zhang, Shanhui Zheng, Yongpeng Pan, Ting Jin, and Yan Li. 2026. "Genome-Wide Analysis of Cellulose Synthase Superfamily and Roles of GmCESA1 in Regulating Drought Tolerance and Growth of Soybean" Plants 15, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010034

APA StyleWu, C., Chen, J., He, J., Zhang, X., Zheng, S., Pan, Y., Jin, T., & Li, Y. (2026). Genome-Wide Analysis of Cellulose Synthase Superfamily and Roles of GmCESA1 in Regulating Drought Tolerance and Growth of Soybean. Plants, 15(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010034