Long-Term Excess Nitrogen Fertilizer Reduces Sorghum Yield by Affecting Soil Bacterial Community

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Sorghum Growth Characteristics and Yield Components

2.2. Soil Properties in Field Experiments

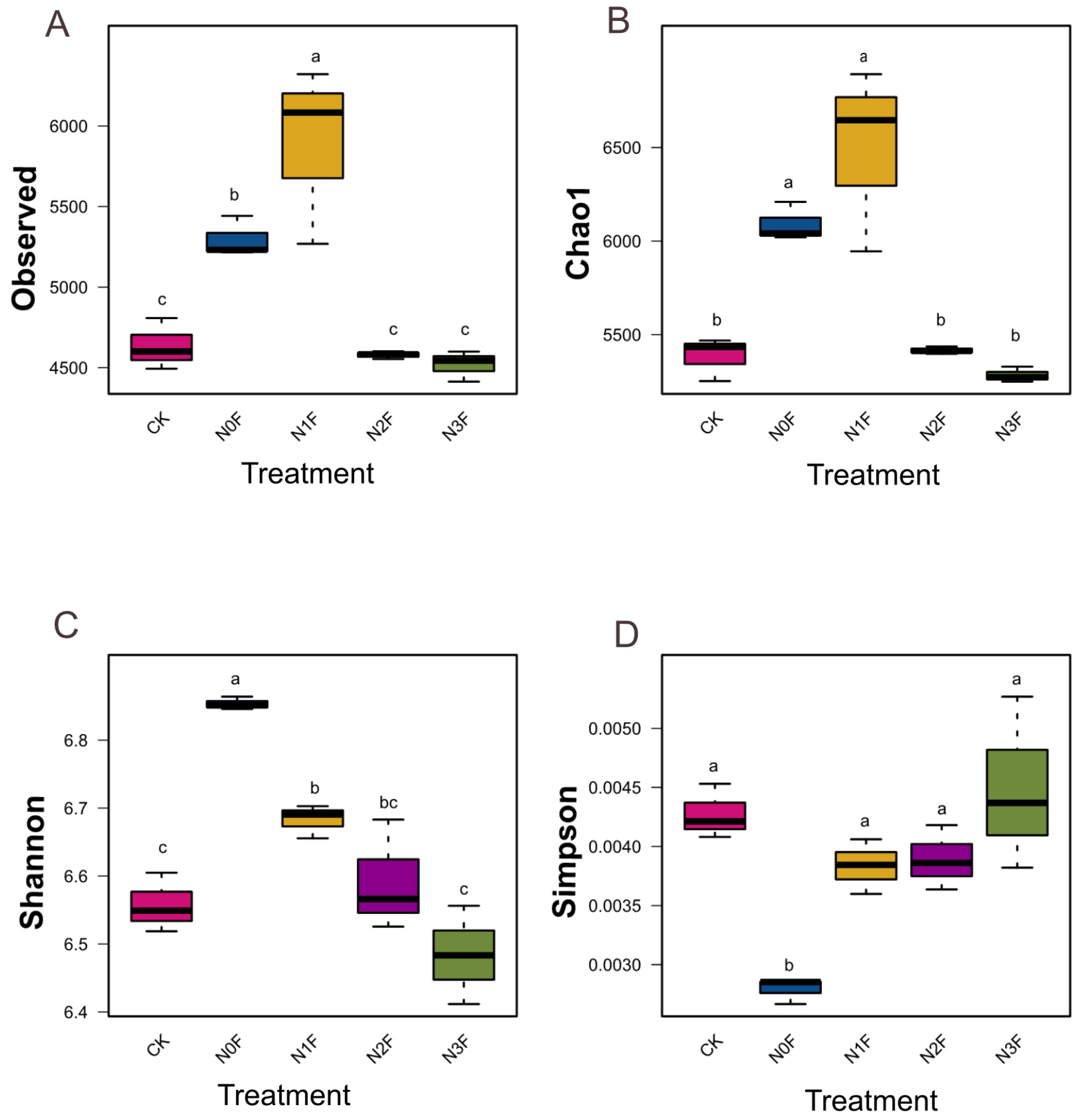

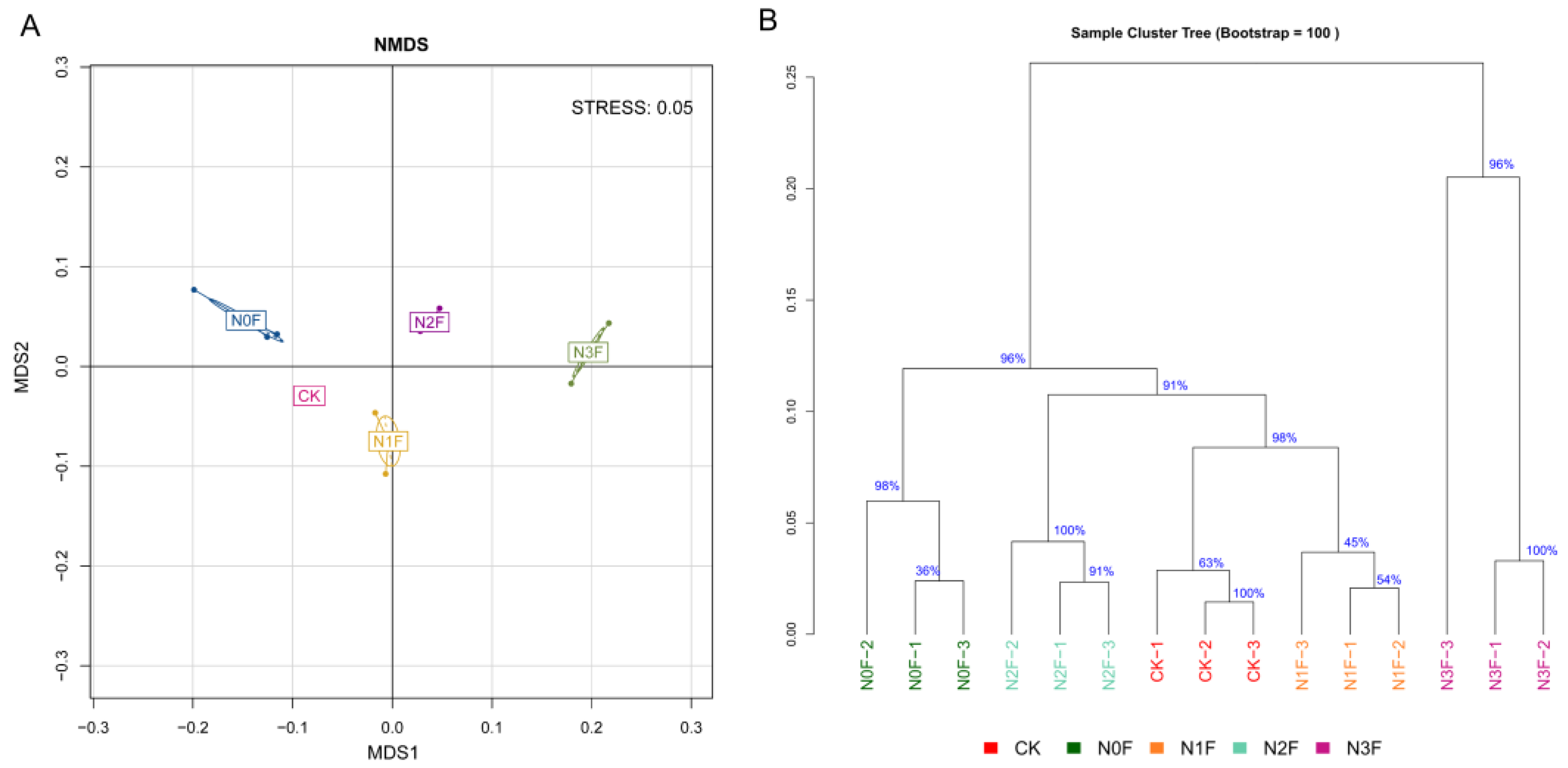

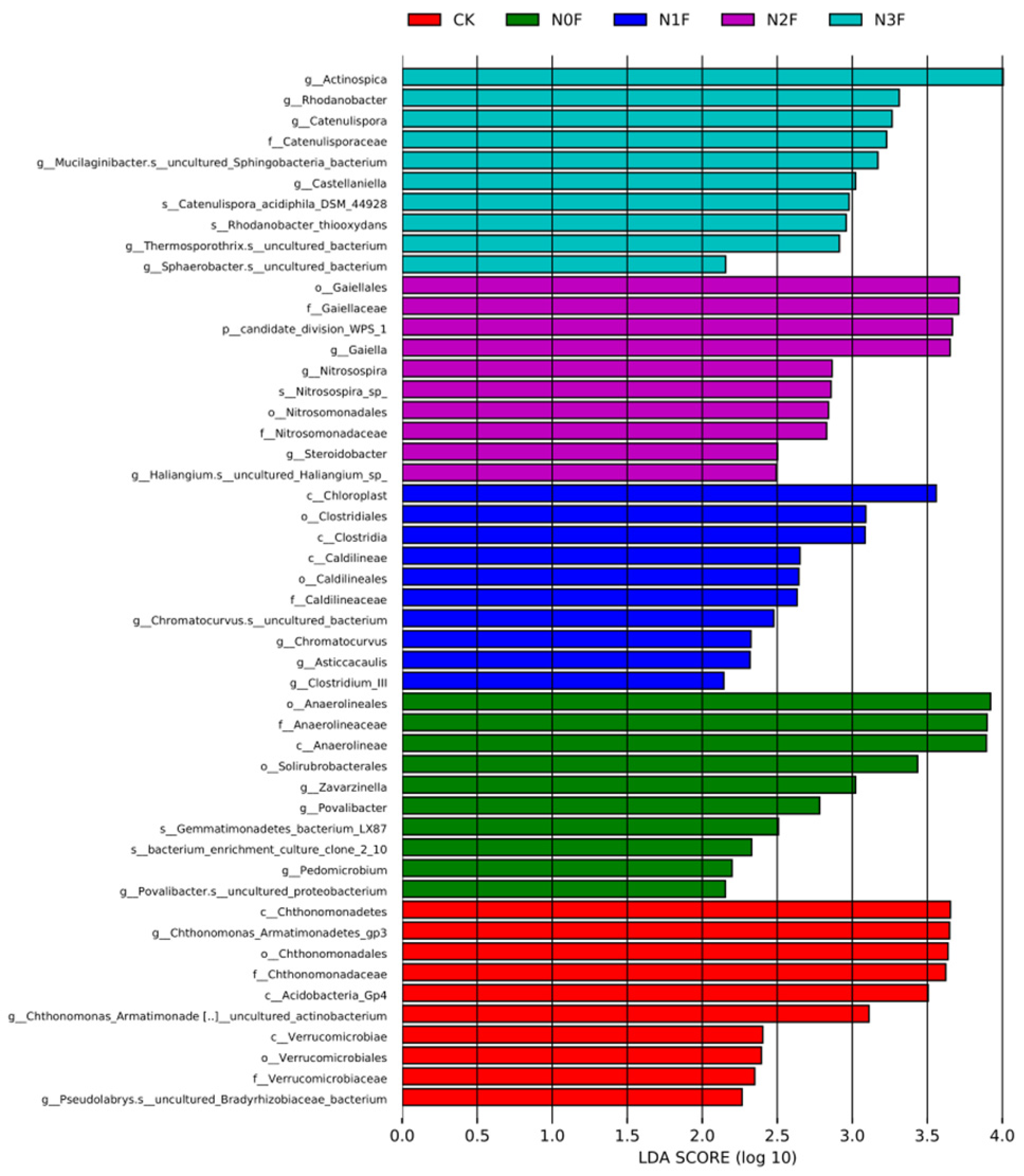

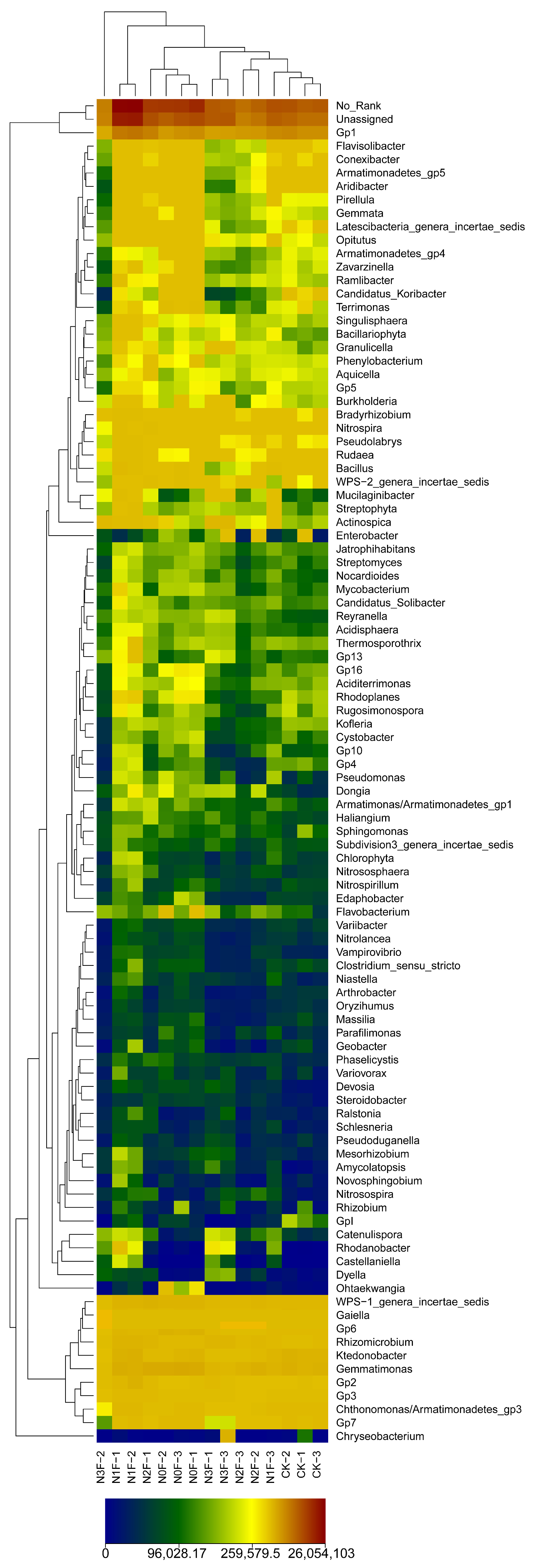

2.3. Bacterial Communities in Different Fertilized Soils

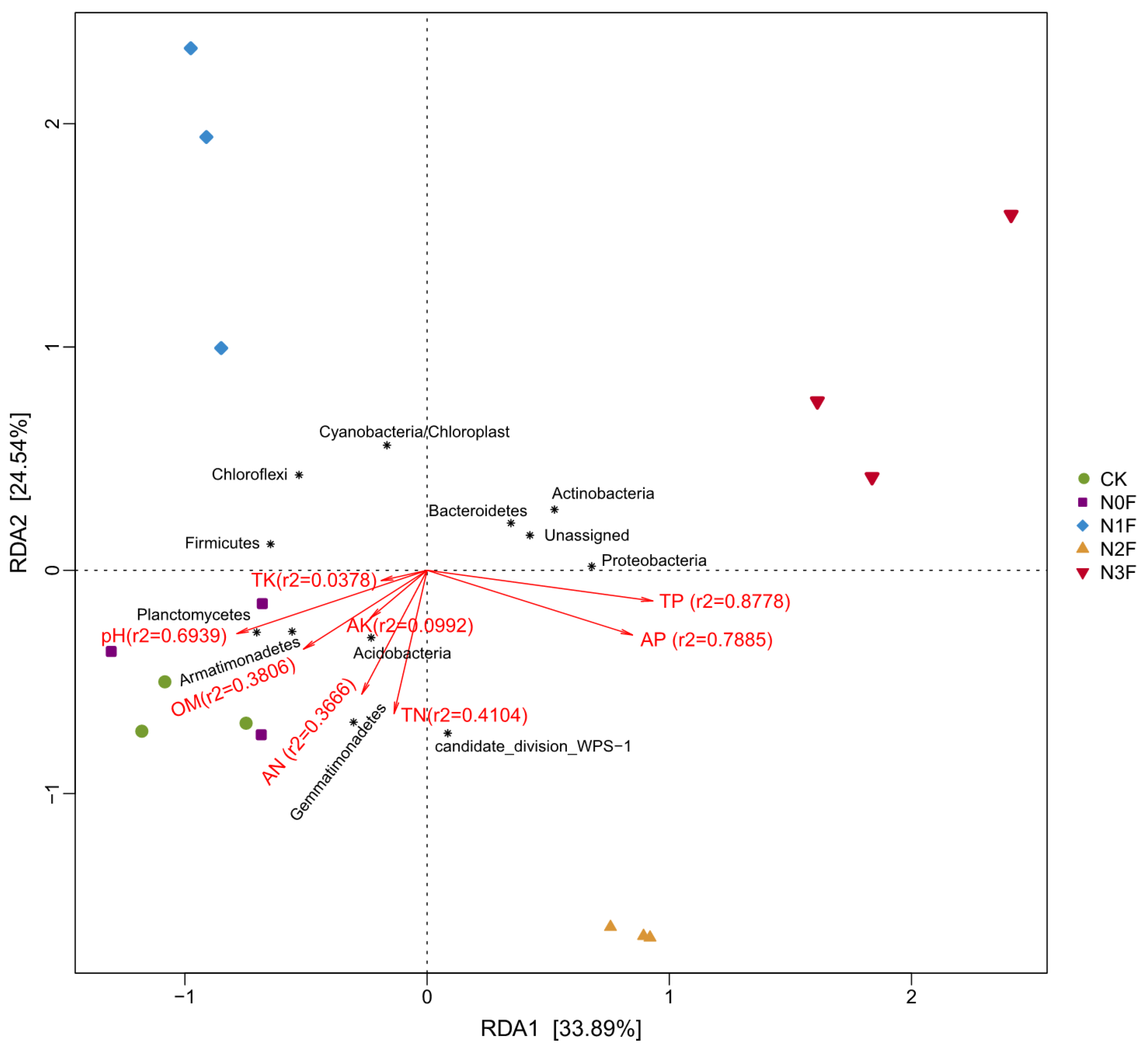

2.4. Relationships Between the Community of Soil Microbiome and the Chemical Properties

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Site and Climatic Conditions

4.2. Field Experiment Design

4.3. Sample Preparation and Analyses

4.4. Soil Property Determination

4.5. DNA Extraction and Absolute Quantification of 16S rRNA

4.6. Illumina Read Data Processing and Analysis and Absolute Quantification of 16S rRNA

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AN | Alkaline hydrolysis nitrogen |

| AP | Available phosphorus |

| AK | Available potassium |

| ANOVA | One-way analysis of variance |

| K | Potassium |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| LEfSe | Linear discriminant analysis effect size |

| N | Nitrogen |

| NMDS | Non-metric multidimensional scaling |

| OM | Organic matter |

| OTU | Operational taxonomic unit |

| P | Phosphorus |

| RDP | Ribosomal Database Project |

| TK | Total potassium |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| TP | Total phosphorus |

Appendix A

References

- Guo, J.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliavini, M.; Asensio, D.; Andreotti, C. Increasing nitrogen cycling in deciduous fruit orchards and vineyards to enhance N use efficiency and reduce N losses—A review. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 167, 127561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willaume, M.; Raynal, H.; Bergez, J.E.; Constantin, J. Optimization of nitrogen management and greenhouse gas balance in agroecological cropping systems in a climate change context. Agric. Syst. 2025, 222, 104182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.Y.; Zhao, X.; Pittelkow, C.M.; Fan, M.S.; Zhang, X.; Yan, X.Y. Optimal nitrogen rate strategy for sustainable rice production in China. Nature 2023, 615, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Xu, M.G.; Li, R.; Zheng, L.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, S.G.; Zhang, W.J.; Duan, Y.H.; Lu, C.A. Achieving high yield and nitrogen agronomic efficiency by coupling wheat varieties with soil fertility. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, S.A.; Hamani, A.K.M.; Chen, J.S.; Sun, W.H.; Wang, G.S.; Gao, Y.; Duan, A.W. Optimizing N-fertigation scheduling maintains yield and mitigates global warming potential of winter wheat field in North China Plain. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lei, Y.D.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Liu, J.G.; Shi, X.Y.; Jia, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, F.; Chu, Q.Q. Rational trade-offs between yield increase and fertilizer inputs are essential for sustainable intensification: A case study in wheat-maize cropping systems in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 679, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.L.; Jin, X.L.; Huang, S.W.; Zhu, X.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhang, A.F.; Wang, X.D.; Tong, Y.N.; Hussain, Q.; et al. Carbon and nitrogen footprints of apple orchards in China’s Loess Plateau under different fertilization regimes. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Lauber, C.L.; Ramirez, K.S.; Zaneveld, J.; Bradford, M.A.; Knight, R. Comparative metagenomic, phylogenetic and physiological analyses of soil microbial communities across nitrogen gradients. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.F.; Zhang, A.F.; Huang, S.W.; Han, J.L.; Jin, X.L.; Shen, X.G.; Hussain, Q.; Wang, X.D.; Zhou, J.B.; Chen, Z.J. Optimizing management practices under straw regimes for global sustainable agricultural production. Agronomy 2023, 13, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.X.; Liu, W.J.; Tang, S.R.; Yang, Q.; Meng, L.; Wu, Y.Z.; Wang, J.J.; Wu, L.; Wu, M.; Xue, X.X.; et al. Long-term partial substitution of chemical nitrogen fertilizer with organic fertilizers increased SOC stability by mediating soil C mineralization and enzyme activities in a rubber plantation of Hainan Island, China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 182, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Yan, K.; Tang, L.S.; Jia, Z.J.; Li, Y. Change in deep soil microbial communities due to long-term fertilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 75, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shangguan, Z.P. Long-term N addition accelerated organic carbon mineralization in aggregates by shifting microbial community composition. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 342, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.X.; Yan, B.S.; Wei, F.R.; Wang, H.L.; Gao, L.Q.; Ma, H.Z.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.B.; Wang, G.L. Long-term application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers changes the process of community construction by affecting keystone species of crop rhizosphere microorganisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 897, 165239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.D.; Xiao, J.; Liang, T.; He, W.Z.; Tan, H.W. Response of soil biological properties and bacterial diversity to different levels of nitrogen application in sugarcane fields. AMB Express 2021, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.S.; Gupta, V.K. Soil microbial biomass: A key soil driver in management of ecosystem functioning. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Lu, P.N.; Feng, S.J.; Hamel, C.; Sun, D.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Gan, G.Y. Strategies to improve soil health by optimizing the plant–soil–microbe–anthropogenic activity nexus. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 359, 108750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossolani, J.W.; Leite, M.F.A.; Momesso, L.; Berge, H.T.; Bloem, J.; Kuramae, E.E. Nitrogen input on organic amendments alters the pattern of soil–microbe-plant co-dependence. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 890, 164347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, W.; Chen, X.L.; Thakur, M.P.; Kardol, P.; Lu, X.M.; Bai, Y.F. Trophic regulation of soil microbial biomass under nitrogen enrichment: A global meta-analysis. Funct. Ecol. 2024, 38, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D.; Feng, J.G.; Ao, G.; Qin, W.K.; Han, M.G.; Shen, Y.W.; Liu, M.L.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, B. Globally nitrogen addition alters soil microbial community structure, but has minor effects on soil microbial diversity and richness. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 179, 108982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Roley, S.S.; Duncan, D.S.; Guo, J.R.; Quensen, J.F.; Yu, H.Q.; Tiedje, J.M. Long-term excess nitrogen fertilizer increases sensitivity of soil microbial community to seasonal change revealed by ecological network and metagenome analyses. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 160, 108349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, W.; Leff, J.W.; Bradford, M.A.; McCulley, R.L.; Lebeer, S.; Fierer, N. A method for simultaneous measurement of soil bacterial abundances and community composition via 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 96, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacz, A.; Hortala, M.; Poole, P.S. Absolute quantitation of microbiota abundance in environmental samples. Microbiome 2018, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishna, D.; Vinodh, R.; Madhu, P.; Avinash, S.; Rajappa, P.V.; Bhat, B.V. Chapter 7—Tissue culture and genetic transformation in Sorghum bicolor. In Breeding Sorghum for Diverse End Uses; Aruna, C., Visarada, K.B.R.S., Bhat, B.V., Tonapi, V.A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2019; pp. 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, A.H.; Bowers, J.E.; Bruggmann, R.; Dubchak, I.; Grimwood, J.; Gundlach, H.; Haberer, G.; Hellsten, U.; Mitros, T.; Poliakov, A.; et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature 2009, 457, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C.; Li, Y.C. The role of nutrient efficient plants in improving crop yields in the twenty first century. J. Plant Nutr. 2008, 31, 1121–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.B.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, Y.Q. Yield and quality in main and ratoon crops of grain sorghum under different nitrogen rates and planting densities. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 778663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Nie, T.Z.; Lu, D.H.; Zhang, P.; Li, J.F.; Li, F.H.; Zhang, Z.X.; Chen, P.; Jiang, L.L.; Dai, C.L.; et al. Effects of different irrigation management and nitrogen rate on sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) growth, yield and soil nitrogen accumulation with drip irrigation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollam, S.; Romana, K.K.; Rayaprolu, L.; Vemula, A.; Das, R.R.; Rathore, A.; Gandham, P.; Chander, G.; Deshpande, S.P.; Gupta, R. Nitrogen use efficiency in sorghum: Exploring native variability for traits under variable N-regimes. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 643192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirel, B.; Le Gouis, J.; Ney, B.; Gallais, A. The challenge of improving nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants: Towards a more central role for genetic variability and quantitative genetics within integrated approaches. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 2369–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Xie, H.X.; Ren, Z.H.; Li, T.; Wen, X.X.; Han, J.; Liao, Y.C. Response of N2O emissions to N fertilizer reduction combined with biochar application in a rain-fed winter wheat ecosystem. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 333, 107968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, D.; Menossi, M.; Mattiello, L. Nitrogen supply influences photosynthesis establishment along the sugarcane leaf. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdoff, F.; Lanyon, L.; Liebhardt, B. Nutrient cycling, transformations, and flows: Implications for a more sustainable agriculture. Adv. Agron. 1997, 60, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, K.A.; Lu, Z.; Shen, Z.; Daba, N.A.; Li, J.W.; Alam, M.A.; Lisheng, L.; Gilbert, N.; Legesse, T.G.; Huimin, Z. Impacts of long-term chemical nitrogen fertilization on soil quality, crop yield, and greenhouse gas emissions: With insights into post-lime application responses. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 944, 173827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, P.S.; Li, J.K.; Chen, P.; Wei, D.D.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Jia, Z.J.; He, C.; Ullah, J.; Wang, Q.; Ruan, Y.Z. Mitigating soil degradation in continuous cropping banana fields through long-term organic fertilization: Insights from soil acidification, ammonia oxidation, and microbial communities. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 213, 118385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.J.; Gu, H.D.; Liu, J.J.; Wei, D.; Zhu, P.; Cui, X.A.; Zhou, B.K.; Chen, X.L.; Jin, J.; Wang, G.H. Different long-term fertilization regimes affect soil protists and their top-down control on bacterial and fungal communities in Mollisols. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Q.; Kuzyakov, Y. Soil organic matter priming: The pH effects. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, 17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.F.; Delhaize, E.; Zhou, M.X.; Ryan, P.R. Biotechnological solutions for enhancing the aluminium resistance of crop plants. In Abiotic Stress in Plants—Mechanisms and Adaptations; InTech: London, UK, 2011; Volume 6, pp. 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ahnemann, H.; Arlotti, D.; Huyghebaert, B.; Cuperus, F.; Tebbe, C.C. Impact of diversified cropping systems and fertilization strategies on soil microbial abundance and functional potentials for nitrogen cycling. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 932, 172954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.S.; Massart, S.; Li, G.H.; Zhang, J.F. Root processes counteract the suppression of nitrogen-induced priming effects by enhancing microbial activity and catabolism in greenhouse vegetable production systems. Soil Tillage Res. 2026, 255, 106802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Su, L.B.; Jing, M.; Wang, K.Q.; Song, C.G.; Song, Y.L. Nitrogen addition restricts key soil ecological enzymes and nutrients by reducing microbial abundance and diversity. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Cao, X.X.; Chen, M.M.; Lou, Y.H.; Wang, H.; Yang, Q.G.; Pan, H.; Zhuge, Y.P. Effects of soil acidification on bacterial and fungal communities in the Jiaodong Peninsula, Northern China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzke, F.; Wang, L.; Chesneau, G.; Böhringer, N.; Mesny, F.; Denissen, N.; Wesseler, H.; Adisa, P.T.; Marner, M.; Schulze-Lefert, P.; et al. Physiochemical interaction between osmotic stress and a bacterial exometabolite promotes plant disease. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.Q.; Yu, Y.N.; Gao, R.W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Long, X.H.; Shen, Q.R.; Chen, W.; Cai, F. High-throughput absolute quantification sequencing reveals the effect of different fertilizer applications on bacterial community in a tomato cultivated coastal saline soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 687, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichorst, S.A.; Kuske, C.R.; Schmidt, T.M. Influence of plant polymers on the distribution and cultivation of bacteria in the phylum Acidobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belova, S.E.; Naumoff, D.G.; Suzina, N.E.; Kovalenko, V.V.; Loiko, N.G.; Sorokin, V.V.; Dedysh, S.N. Building a cell house from cellulose: The case of the soil acidobacterium Acidisarcina polymorpha SBC82T. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayatsu, M.; Tago, K.; Saito, M. Various players in the nitrogen cycle: Diversity and functions of the microorganisms involved in nitrification and denitrification. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2008, 54, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, L.A.; Castelle, C.J.; Wrighton, K.C.; Thomas, B.C.; Sharon, I.; Frischkorn, K.R.; Williams, K.H.; Tringe, S.G.; Banfield, J.F. Community genomic analyses constrain the distribution of metabolic traits across the Chloroflexi phylum and indicate roles in sediment carbon cycling. Microbiome 2013, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Bradford, M.A.; Jackson, R.B. Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology 2007, 88, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G.M.; Jiang, L.; Han, X.G. Mechanisms of soil acidification reducing bacterial diversity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 81, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.J.; Prakash, O.; Jasrotia, P.; Overholt, W.A.; Cardenas, E.; Hubbard, D.; Tiedje, J.M.; Watson, D.B.; Schadt, C.W.; Brooks, S.C.; et al. Denitrifying bacteria from the genus Rhodanobacter dominate bacterial communities in the highly contaminated subsurface of a nuclear legacy waste site. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Six, J. Soil structure and microbiome functions in agroecosystems. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, L.A.; Baker, B.J.; Anantharaman, K.; Brown, C.T.; Probst, A.J.; Castelle, C.J.; Butterfield, C.N.; Hernsdorf, A.W.; Amano, Y.; Ise, K.; et al. A new view of the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaby, J.C.; Buckley, D.H. A comprehensive aligned nifH gene database: A multipurpose tool for studies of nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Database 2014, 2014, bau001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Liu, X.J.; Song, L.; Lin, X.G.; Zhang, H.Z.; Shen, C.C.; Chu, H.Y. Nitrogen fertilization directly affects soil bacterial diversity and indirectly affects bacterial community composition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 92, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Schlaeppi, K.; Banerjee, S.; Kuramae, E.E.; Van Der Heijden, M.G.A. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.J.; Dai, H.X.; He, Y.; Liang, T.B.; Zhai, Z.; Zhang, S.X.; Hu, B.B.; Cai, H.Q.; Dai, B.; Xu, Y.D.; et al. Continuous cropping system altered soil microbial communities and nutrient cycles. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1374550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahram, M.; Hildebrand, F.; Forslund, S.K.; Anderson, J.L.; Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; Bodegom, P.M.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Anslan, S.; Coelho, L.P.; Harend, H.; et al. Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature 2018, 560, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: Disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, L.A.; Riazi, A.; Smith, C.J. A semi-micro method for determining total nitrogen in soils and plant material containing nitrite and nitrate. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R.; Cole, C.V.; Watanabe, F.S.; Dean, L.A. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.B., Jr.; Case, V.W. Sampling, handling, and analyzing plant tissue samples. In Soil Testing and Plant Analysis; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. A further biodiversity index applicable to species lists: Variation in taxonomic distinctness. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 216, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Plant Height (cm) | Ear Length (cm) | 1000-Grain Weight (g) | Ear Grain Weight (g) | Yield (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 150.37 ± 10.92 b | 30.64 ± 2.41 b | 26.13 ± 1.12 a | 35.50 ± 2.92 b | 3205.56 ± 232.38 c |

| N0F | 154.53 ± 9.67 b | 31.77 ± 1.19 b | 26.62 ± 0.97 a | 38.93 ± 3.13 b | 3540.28 ± 231.14 c |

| N1F | 179.27 ± 1.22 a | 34.74 ± 0.59 a | 27.29 ± 2.07 a | 61.46 ± 3.52 a | 5622.22 ± 146.86 ab |

| N2F | 182.80 ± 2.04 a | 35.59 ± 0.62 a | 28.78 ± 2.63 a | 64.74 ± 3.29 a | 5954.17 ± 82.07 a |

| N3F | 184.00 ± 1.97 a | 35.61 ± 1.08 a | 28.36 ± 0.54 a | 64.71 ± 1.62 a | 5471.94 ± 197.50 b |

| Treatment | pH | AN (mg kg−1) | AP (mg kg−1) | AK (mg kg−1) | OM (g kg−1) | TN (g kg−1) | TP (g kg−1) | TK (g kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 5.44 ± 0.03 a | 44.82 ± 1.98 c | 10.46 ± 0.33 c | 96.23 ± 1.49 d | 10.29 ± 0.04 d | 0.36 ± 0.01 d | 0.33 ± 0.01 b | 20.60 ± 0.36 b |

| N0F | 5.37 ± 0.02 b | 53.86 ± 1.42 a | 9.39 ± 0.16 d | 101.70 ± 1.49 c | 13.24 ± 0.23 a | 0.53 ± 0.02 b | 0.32 ± 0.03 b | 19.94 ± 0.48 b |

| N1F | 4.93 ± 0.02 c | 48.58 ± 0.56 b | 8.64 ± 0.16 e | 109.66 ± 0.99 b | 10.77 ± 0.20 c | 0.40 ± 0.01 c | 0.30 ± 0.01 b | 22.13 ± 0.46 a |

| N2F | 4.82 ± 0.02 d | 56.30 ± 1.73 a | 11.28 ± 0.23 b | 113.64 ± 1.49 a | 11.23 ± 0.20 b | 0.57 ± 0.01 a | 0.39 ± 0.02 a | 22.04 ± 0.76 a |

| N3F | 4.74 ± 0.02 e | 41.05 ± 0.86 d | 12.41 ± 0.35 a | 90.92 ± 1.25 e | 9.43 ± 0.34 e | 0.32 ± 0.02 e | 0.42 ± 0.03 a | 19.60 ± 0.48 b |

| Alpha-Diversity Index | Correlation Coefficient (r) | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed species | −0.433 | 0.103 | NS |

| Chao1 | −0.442 | 0.094 | NS |

| Shannon | −0.634 | 0.010 | ** |

| Simpson | 0.585 | 0.021 | * |

| Abundant Taxa | pH | AN | AP | AK | OM | TN | TP | TK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acidobacteria | 0.280 | 0.306 | −0.956 * | 0.557 | 0.360 | 0.136 | −0.899 * | 0.599 |

| Proteobacteria | −0.079 | 0.375 | −0.781 | 0.508 | 0.498 | 0.272 | −0.572 | 0.366 |

| Chloroflexi | 0.240 | 0.024 | −0.905 * | 0.301 | 0.207 | −0.137 | −0.861 | 0.395 |

| Actinobacteria | −0.030 | 0.002 | −0.746 | 0.200 | 0.254 | −0.109 | −0.600 | 0.178 |

| Bacteroidetes | 0.011 | 0.185 | −0.483 | 0.030 | 0.571 | 0.180 | −0.294 | −0.242 |

| Planctomycetes | 0.351 | 0.489 | −0.958 * | 0.503 | 0.701 | 0.372 | −0.840 | 0.340 |

| Gemmatimonadetes | 0.618 | 0.790 | −0.749 | 0.547 | 0.923 * | 0.732 | −0.703 | 0.264 |

| Armatimonadetes | 0.676 | 0.365 | −0.965 ** | 0.378 | 0.590 | 0.231 | −0.988 ** | 0.329 |

| candidate_division_WPS-1 | 0.319 | 0.859 | −0.782 | 0.745 | 0.877 | 0.782 | −0.643 | 0.465 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, L.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y. Long-Term Excess Nitrogen Fertilizer Reduces Sorghum Yield by Affecting Soil Bacterial Community. Plants 2026, 15, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010025

Wang Q, Huang J, Zhang Y, Li Z, Wei L, Yin X, Zhang X, Zhou Y. Long-Term Excess Nitrogen Fertilizer Reduces Sorghum Yield by Affecting Soil Bacterial Community. Plants. 2026; 15(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qiuyue, Juan Huang, Yaqin Zhang, Zebi Li, Ling Wei, Xuewei Yin, Xiaochun Zhang, and Yu Zhou. 2026. "Long-Term Excess Nitrogen Fertilizer Reduces Sorghum Yield by Affecting Soil Bacterial Community" Plants 15, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010025

APA StyleWang, Q., Huang, J., Zhang, Y., Li, Z., Wei, L., Yin, X., Zhang, X., & Zhou, Y. (2026). Long-Term Excess Nitrogen Fertilizer Reduces Sorghum Yield by Affecting Soil Bacterial Community. Plants, 15(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010025