Phenotypic Variability and Genetic Diversity Analysis of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Germplasm Resources

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

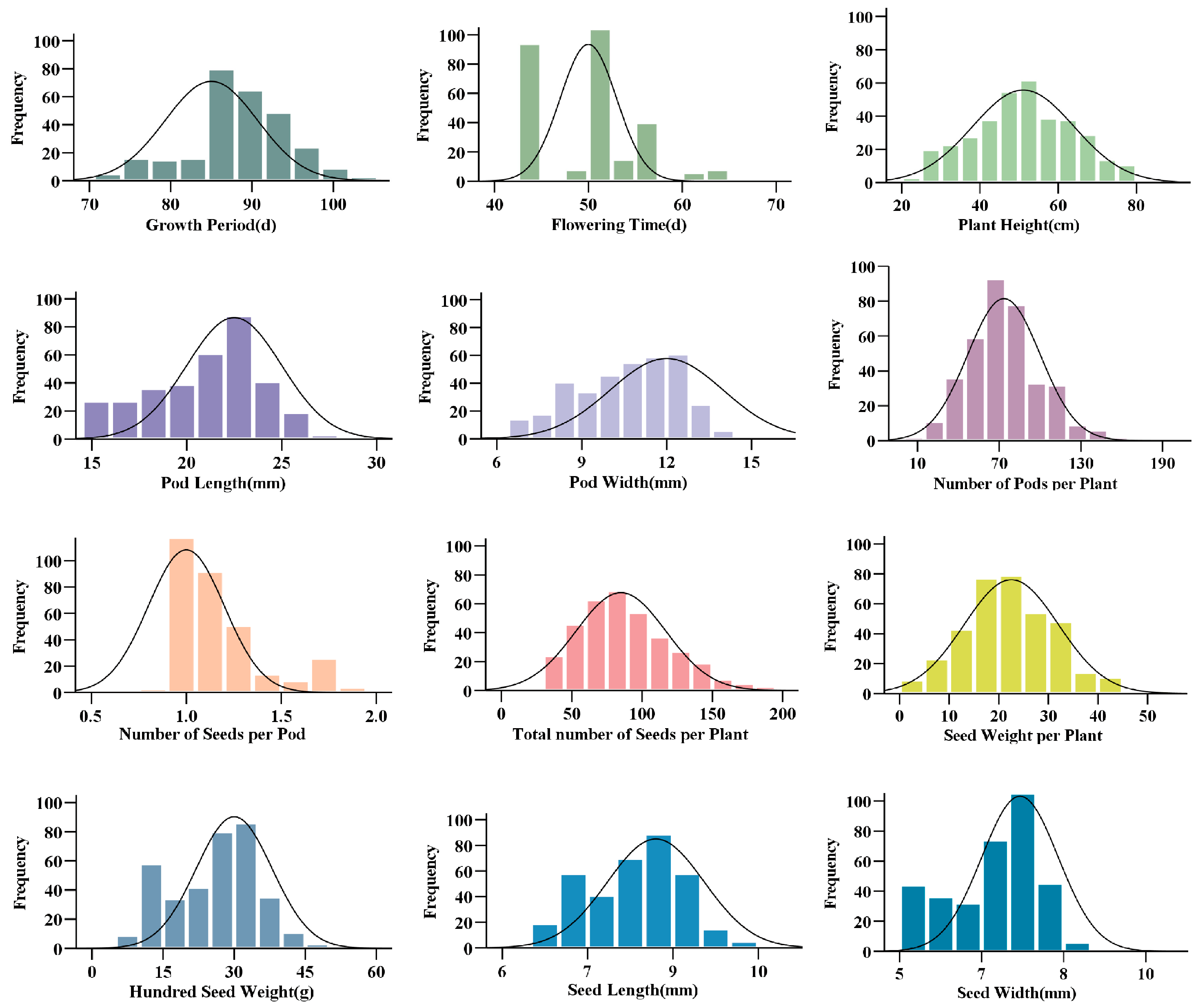

2.1. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Main Agronomic Traits

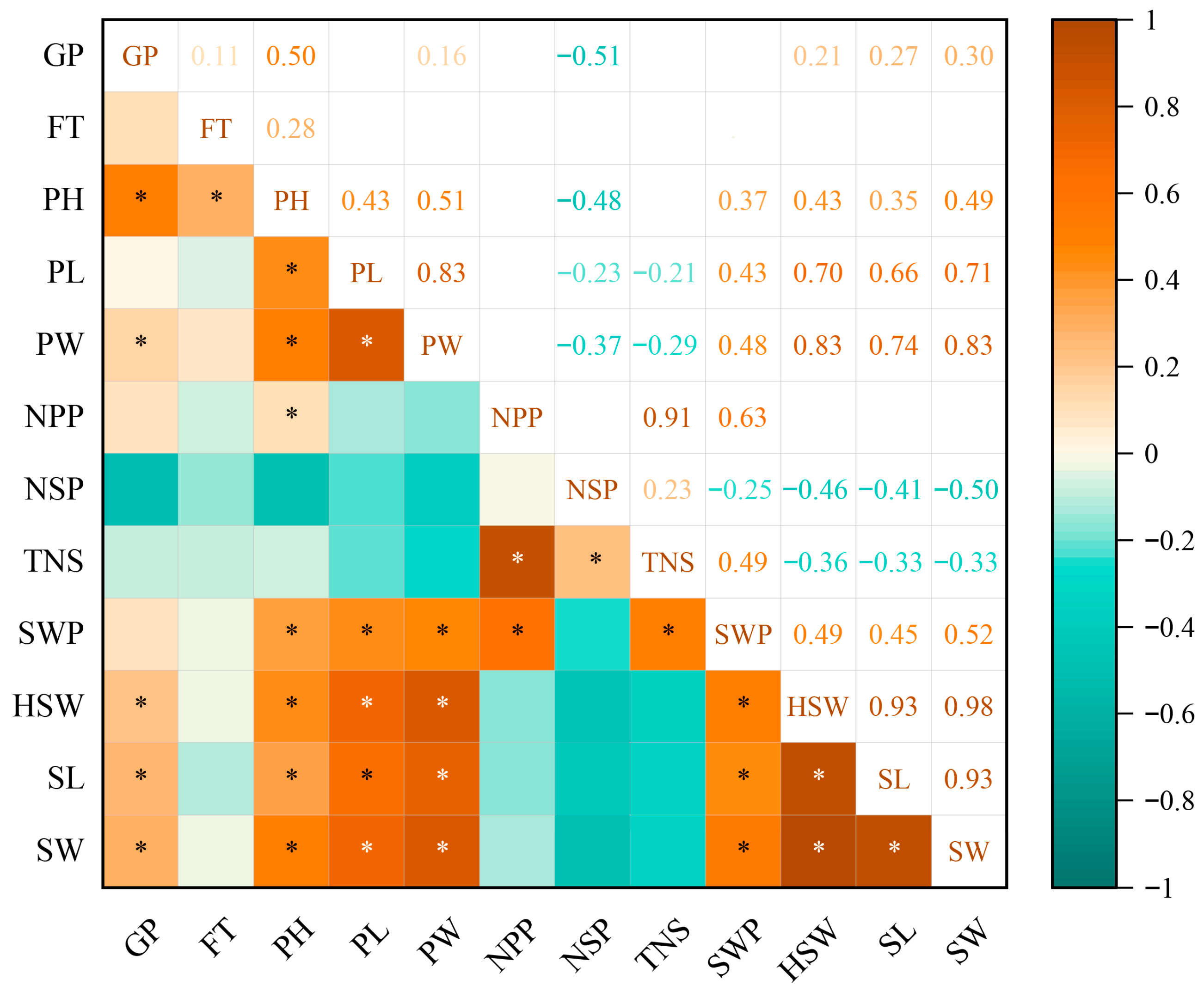

2.2. Correlation Analysis of 12 Quantitative Traits

2.3. Principal Component Analysis of Main Agronomic Traits and Quality Traits

0.173X8 − 0.013X9 + 0.169X10 + 0.153X11 + 0.173X12 + 0.023X13 − 0.013X14 −

0.021X15 + 0.042X16

0.039X8 + 0.201X9 + 0.131X10 + 0.175X11 + 0.135X12 − 0.148X13 − 0.023X14 +

0.02X15 + 0.095X16

0.039X8 − 0.214X9 − 0.135X10 − 0.108X11 − 0.112X12 + 0.018X13 − 0.154X14 +

0.106X15 + 0.116X16

0.191X8 + 0.284X9 − 0.024X10 − 0.057X11 − 0.026X12 + 0.388X13 + 0.077X14 −

0.131X15 + 0.387X16

0.022X8 − 0.287X9 + 0.035X10 + 0.004X11 − 0.011X12 + 0.101X13 + 0.668X14

− 0.562X15 − 0.044X16

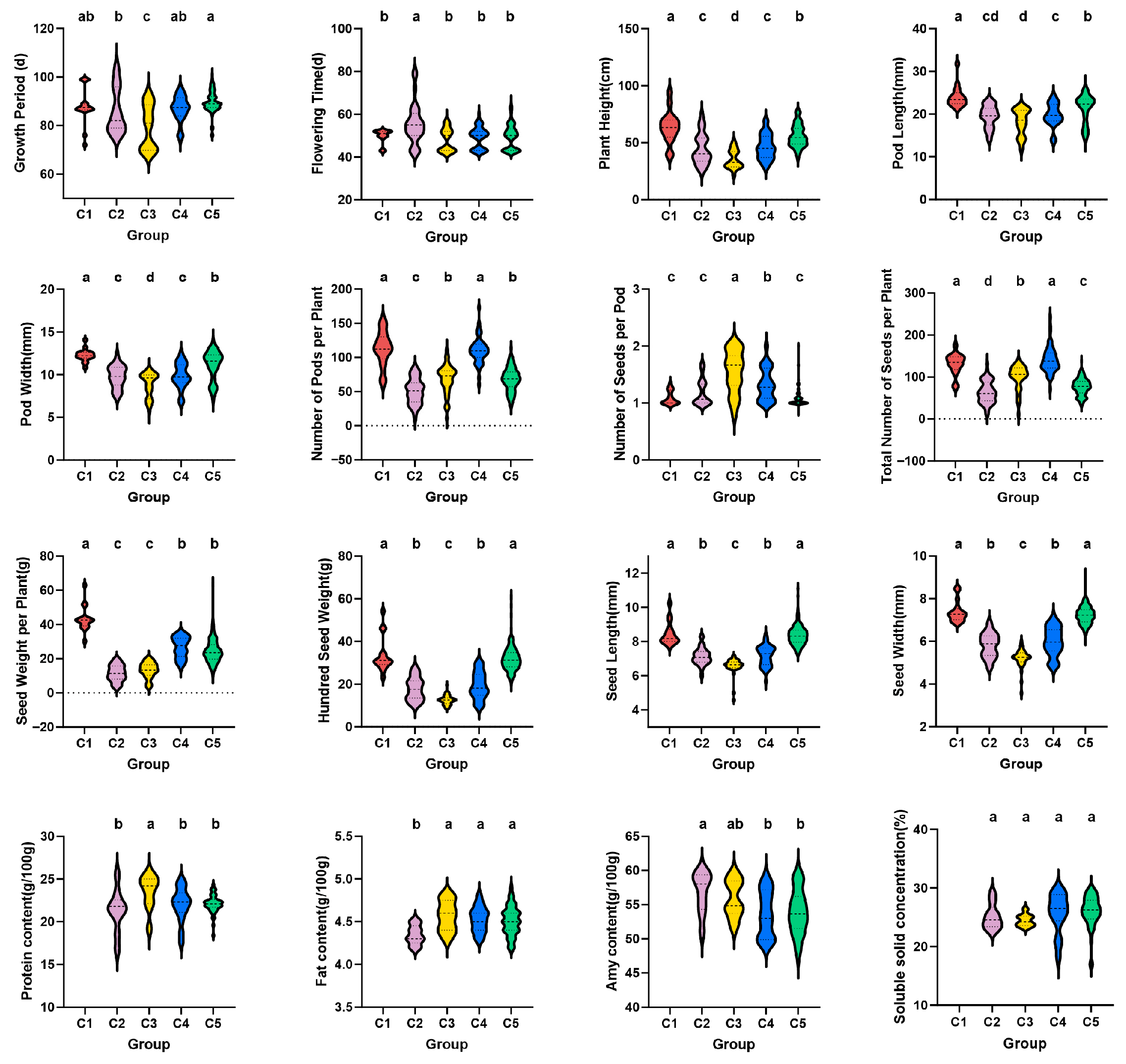

2.4. Cluster Analysis of 362 Chickpea Germplasm Resources

2.5. Comprehensive Evaluation of Chickpea Germplasm Resources and Screening of Excellent Resources

3. Discussion

3.1. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Chickpea Germplasm Resources

3.2. Relationships and Cluster Analysis of Quantitative and Quality Traits in Chickpea Germplasm

3.3. Principal Component Analysis and Comprehensive Evaluation of Phenotypic and Quality Traits in Chickpea Germplasm

4. Materials and Methods

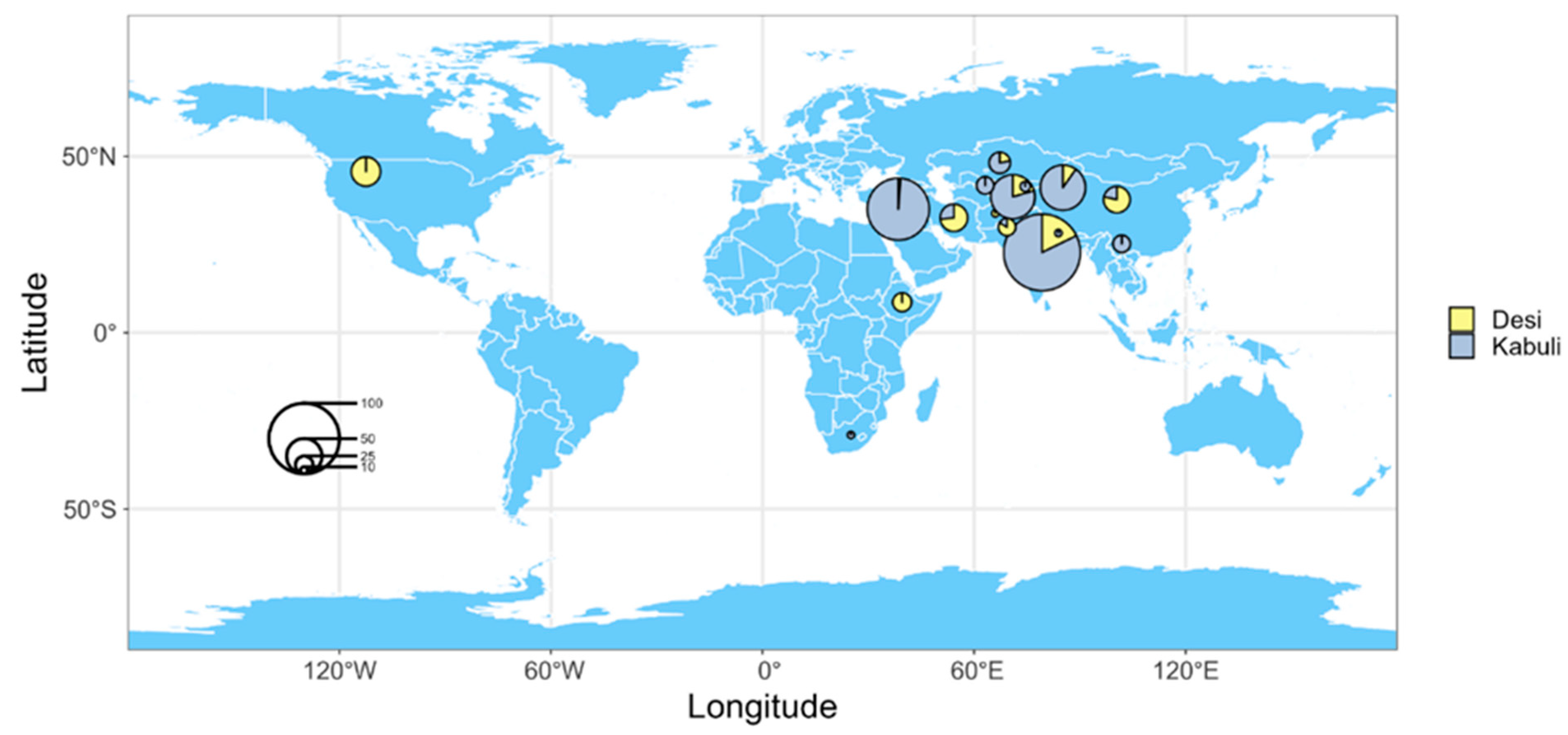

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Design of Experiment

4.3. Investigation of Main Agronomic Traits

4.4. Determination of Grain Quality Traits

4.4.1. Protein Content

4.4.2. Fatty Acid Content

4.4.3. Amylum Content, Soluble Solid Concentration Content

4.5. Statistical and Analytical Processing of Data

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| H′ | Genetic diversity index |

| h2 | Narrow-sense heritability |

| GP | Growth period |

| FT | Flowering time |

| PH | Plant height |

| NPP | Number of pods per plant |

| NSP | Number of Seeds per Pod |

| TNS | Total number of seeds per plant |

| SWP | Seed weight per plant |

| HSW | Hundred-seed weight |

| PL | Pod Length |

| PW | Pod Width |

| SL | Seed Length |

| SW | Seed Width |

| PT | Plant type |

| FC | Flower color |

| LC | Leaf Color |

| SS | Seed shape |

| SCC | Seed coat color |

| SSS | Seed surface shape |

| PC | Protein content |

| FC | Fat content |

| AC | Amy content |

| SSCC | Soluble solid concentration content |

| H2 | Broad-sense heritability |

References

- Knights, E.J.; Hobson, K.B. Chickpea: Overview. In Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, P.M.; Samineni, S.; Sajja, S.; Chibbar, R.N. Achievements and Challenges in Improving Nutritional Quality of Chickpea. Legume Perspect. 2015, 9, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.B.; Miao, H.C.; Wang, W.; Xiao, J.; Li, L.M. Genetic Diversity of Chickpea Germplasm Resources was Analyzed by SSR markers. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2015, 16, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Diapari, M.; Sindhu, A.; Bett, K.; Deokar, A.; Warkentin, T.D.; Tar’an, B. Genetic Diversity and Association mapping of Iron and Zinc Concentrations in Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Genome 2014, 57, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.B.; Kaliyaperumal, A.; Diapari, M.; Ambrose, S.J.; Zhang, H.X.; Tar’an, B.; Bett, K.E.; Vandenberg, A.; Warkentin, T.D.; Purves, R.W. Genetic Diversity of Folate Profiles in Seeds of Common Bean, Lentil, Chickpea and Pea. Food Compos. 2015, 42, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.H.; Khoshro, H.H.; Kanouni, H.; Shobeiri, S.S.; Ashour, B.M. Identifying Dryland-resilient Chickpea Genotypes for Autumn sowing with a focus on Multi-trait Stability Parameters and Biochemical Enzyme activity. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, L.H.; Jia, J.Z. Theoretical Framework and Development strategy for the Science of Crop germplasm resources. Plant Genet. Resour. 2023, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Varshney, R.K.; Roorkiwal, M.; Sun, S.; Bajaj, P.; Chitikineni, A.; Thudi, M.; Singh, N.P.; Du, X.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Khan, A.W.; et al. A Chickpea Genetic Variation map based on the Sequencing of 3366 Genomes. Nature 2021, 599, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, R.K.; Thudi, M.; Roorkiwal, M.; He, W.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Yang, W.; Bajaj, P.; Cubry, P.; Rathore, A.; Jian, J.; et al. Resequencing of 429 Chickpea Accessions from 45 Countries Provides Insights into Genome Diversity, Domestication and Agronomic traits. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.W.; Garg, V.; Sun, S.; Gupta, S.; Dudchenko, O.; Roorkiwal, M.; Chitikineni, A.; Bayer, P.E.; Shi, C.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; et al. Cicer Super-pangenome Provides Insights into Species Evolution and Agronomic trait Loci for crop Improvement in Chickpea. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.T.; Yang, F.; Lv, M.Y.; Hu, C.Q.; Yang, X.; Zheng, A.Q.; Wang, Y.B.; He, Y.H.; Wang, L.P. Genetic diversity analysis and comprehensive evaluation of agronomic traits of Iranian chickpea germplasm resources. South Agric. 2021, 52, 769–778. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Q.S.; Guang, Y.B.; Chen, B.W.; Sa, J.D.; Zhou, L.L.; Niu, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.F.; Li, Y.L. Diversity Evaluation of Chickpea Germplasm Resources. Northwest Agric. J. 2017, 26, 1803–1812. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.B.; Guan, Y.B.; Niu, Y.Q.; Zhou, L.L.; Zhao, Y.F. Comprehensive Identification and Evaluation of 12 main Agronomic traits of 103 Chickpea Germplasm Resources. Crops J. 2023, 39, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.X.; Liu, L.L.; Wu, Z.N.; Du, R. Genetic Diversity Analysis of main Agronomic traits of 114 Chickpea Germplasms. Gansu Agric. Univ. 2022, 57, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.Y.; Yang, T.; Liang, J.; Guo, W.Y.; Xiao, H.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Ma, X.F.; Liu, T.T.; Zong, X.X. Genetic Diversity Analysis of main Agronomic traits of 160 Introduced Chickpea Germplasms. Plant Genet Resour. 2020, 21, 875–883. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.B.; Li, L.M.; Miao, H.C.; Wang, W.; Xiao, J.; Re, Y.L. Study on Genetic Diversity of Main Agronomic Traits of Chickpea Germplasm Resources. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2014, 51, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.H. Evaluation and Utilization of Rice Germplasm Resources in China; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.J.; Kong, Q.Q.; Zhao, C.H.; He, X.Y.; Tian, X.Y.; Zhang, X.Q.; Xi, X.M. Genetic Diversity Analysis of main Agronomic traits of Chickpea Germplasm Resources. North Agric. 2018, 46, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, S.H.; Peng, L.; Wang, X.; Ji, L. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Agronomic traits of Chickpea Germplasm Resources. Plant Genet Resour. 2015, 16, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Q.S.; Yang, L. Screening and Diversity Analysis of Chickpea Germplasm Resources. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2017, 45, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dalmaijer, E.S.; Nord, C.L.; Astle, D.E. Statistical power for cluster analysis. BMC Bioinf. 2022, 23, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, S.H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.F.; Wang, G.P. Catkin Phenotypic Diversity and Cluster Analysis of 211 Chinese Chestnut Germplasms. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2020, 53, 4667–4682. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.J.; Qi, Y.J.; Xing, X.H.; Tong, F.; Wang, X. Analysis and Evaluation of Agronomic and Quality traits in soybean Germplasms from Huang-Huai-Hai region. Plant Genet. Resour. 2022, 3, 468–480. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.H.; Li, S.F.; Zhao, Y.D.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, G.G.; Li, H.N.; Quan, C.Z.; Zhang, Q. Study on Important agronomic characters and Genetic diversity of 1775 rice Germplasm Resources. Plant Genet. Resour. 2025, 26, 481–495. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.F.; Qi, H.Z.; Sun, Y.; Feng, X.; Yang, C.P.; Zhou, W.F.; Yan, Z.L.; Qi, X.L. Character Diversity Analysis of New wheat varieties from Different Origins in Huang Huai winter wheat region. Plant Genet. Resour. 2023, 24, 719–731. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.S.; Xiao, J.; Ma, Y.; Tian, C.; Zhao, L.J.; Wang, F.; Song, Y. Identification and Evaluation of Phenotypic Characters and Genetic Diversity Analysis of 169 Tomato Germplasm Resources. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2024, 57, 3671–3687. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H. Principal Component Analysis of Hybrid functional and Vector data. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 5152–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, X.X. Descriptors and Data Standard for Chickpea Germplasm; China Agricultural Science Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.P.; Dai, P.; Yue, X.L.; Yao, R.C.; Han, P.; Dai, S.Y. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Cowpea Germplasm Resources in Hebei Province. Hebei Agric. Sci. 2017, 21, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

| Traits | H’ | Frequency Distribution (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| PT | 1.123 | 19.9 | 17.2 | 57.4 | 4.8 | 0.7 | — | — | — |

| FC | 0.760 | 1.7 | 76.2 | 9.7 | 12.4 | — | — | — | — |

| SS | 0.758 | 72.8 | 18.3 | 9.0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| SCC | 1.203 | 3.0 | 9.0 | 66.2 | 9.6 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 5.4 |

| SSS | 0.800 | 67.4 | 25.7 | 6.9 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Traits | Mean | Max | Min | SD | Range | CV (%) | H’ | H2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP (d) | 87.79 | 105.00 | 69.00 | 6.70 | 36.00 | 7.63 | 1.97 | 53.45 |

| FT (d) | 46.37 | 66.00 | 30.00 | 6.51 | 36.00 | 14.27 | 1.45 | 61.83 |

| PH (cm) | 51.24 | 94.27 | 23.67 | 12.82 | 70.60 | 25.01 | 2.07 | 63.55 |

| PL (mm) | 21.61 | 31.81 | 12.66 | 2.35 | 19.15 | 10.88 | 2.05 | 85.76 |

| PW (mm) | 11.12 | 14.23 | 6.39 | 1.38 | 7.84 | 12.40 | 1.61 | 90.31 |

| NPP | 73.89 | 173.02 | 10.00 | 26.51 | 163.02 | 35.88 | 2.00 | 77.37 |

| NSP | 1.19 | 2.08 | 0.83 | 0.26 | 1.25 | 22.21 | 2.05 | 83.41 |

| TNS | 89.08 | 242.67 | 10.67 | 35.11 | 232.00 | 39.41 | 2.00 | 79.64 |

| SWP (g) | 22.62 | 63.5 | 2.20 | 9.43 | 61.33 | 41.69 | 2.01 | 90.61 |

| HSW (g) | 26.23 | 60.76 | 8.64 | 9.31 | 52.12 | 35.50 | 2.04 | 92.40. |

| SL (mm) | 7.85 | 11.09 | 5.68 | 0.85 | 5.41 | 10.88 | 2.03 | 90.70 |

| SW (mm) | 6.67 | 9.13 | 4.59 | 0.90 | 4.54 | 13.51 | 1.97 | 80.58 |

| Traits | Years | Locations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p Value | F | p Value | |

| GP (d) | 0.621 | −0.454 | 0.206 | 0.245 |

| FT (d) | 0.236 | −0.444 | 0.646 | 0.101 |

| PH (cm) | 0.708 | −0.413 | 0.228 | 0.249 |

| PL (mm) | −0.167 | 0.717 | 0.608 | 0.078 |

| PW (mm) | 0.070 | 0.736 | 0.598 | 0.086 |

| NPP | −0.747 | 0.103 | −0.255 | 0.470 |

| NSP | −0.751 | 0.013 | 0.215 | −0.308 |

| TNS | −0.895 | 0.100 | −0.07 | 0.305 |

| SWP (g) | −0.07 | 0.513 | −0.385 | 0.454 |

| HSW (g) | 0.875 | 0.333 | −0.243 | −0.039 |

| SL (mm) | 0.793 | 0.445 | −0.194 | −0.092 |

| SW (mm) | 0.895 | 0.344 | −0.202 | −0.041 |

| Traits | Principal Components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| GP (d) | 0.621 | −0.454 | 0.206 | 0.245 | −0.021 |

| FT (d) | 0.236 | −0.444 | 0.646 | 0.101 | −0.080 |

| PH (cm) | 0.708 | −0.413 | 0.228 | 0.249 | −0.010 |

| PL (mm) | −0.167 | 0.717 | 0.608 | 0.078 | 0.160 |

| PW (mm) | 0.070 | 0.736 | 0.598 | 0.086 | 0.157 |

| NPP | −0.747 | 0.103 | −0.255 | 0.470 | −0.127 |

| NSP | −0.751 | 0.013 | 0.215 | −0.308 | 0.170 |

| TNS | −0.895 | 0.100 | −0.07 | 0.305 | −0.024 |

| SWP (g) | −0.07 | 0.513 | −0.385 | 0.454 | −0.301 |

| HSW (g) | 0.875 | 0.333 | −0.243 | −0.039 | 0.037 |

| SL (mm) | 0.793 | 0.445 | −0.194 | −0.092 | 0.004 |

| SW (mm) | 0.895 | 0.344 | −0.202 | −0.041 | −0.012 |

| PC (g/100 g) | 0.119 | −0.376 | 0.033 | 0.621 | 0.106 |

| FC (g/100 g) | −0.066 | −0.058 | −0.276 | 0.123 | 0.702 |

| AC (g/00 g) | −0.111 | 0.050 | 0.190 | −0.209 | −0.591 |

| SSCC (%) | 0.216 | 0.243 | 0.208 | 0.619 | −0.046 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.177 | 2.545 | 1.798 | 1.599 | 1.050 |

| Contribution rate (%) | 32.358 | 15.908 | 11.240 | 9.993 | 6.565 |

| Cumulative contribution rate (%) | 32.358 | 48.266 | 59.506 | 69.499 | 76.064 |

| Number | Variety Name | Origin | Type | Comprehensive Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YZD133 | TaYin YZD-2012-22 | Tadzhikistan | kabuli | 0.483 |

| YZD353 | MuLei (India) | India | kabuli | 0.471 |

| YZD109 | 21412 (B) | ICARDA | desi | 0.442 |

| YZD085 | Nepal-2 | Nepal | kabuli | 0.433 |

| YZD077 | PinYing 1 | Xinjiang, China | kabuli | 0.429 |

| YZD083 | MuYing 1 | Xinjiang, China | kabuli | 0.417 |

| YZD359 | Y Zi 14-124-132 | Yunnan, China | kabuli | 0.415 |

| YZD354 | Mu Lei Dali | Xinjiang, China | kabuli | 0.409 |

| YZD061 | 21302 | National Crop Germplasm Repository | kabuli | 0.406 |

| YZD248 | L657 | National Crop Germplasm Repository | kabuli | 0.404 |

| Traits | Standards and Assignment of Values for Trait Investigation |

|---|---|

| GP (d) | The number of days from the second day of sowing to the maturity of the plants |

| FT (d) | From the second day of sowing to the number of days when the plants flower |

| PH (cm) | The vertical distance from the leaf node to the top of the main stem of a mature plant |

| PL (mm) | The length of a mature plant pod from base to tip |

| PW (mm) | The maximum width of the pod of a mature plant |

| NPP | During the maturity period, observe and count the number of mature pods contained in each plant |

| NSP | Observe and count the number of dry grains contained in each pod during the maturation period |

| TNS | Number of grains per mature plant |

| SWP (g) | The weight of seeds contained in a single mature plant |

| HSW (g) | The weight of 100 mature dry seeds |

| SL (mm) | The length of dry seed from the base to the top of mature plants |

| SW (mm) | The width of the widest part of the dry seed of a mature plant |

| PT | 1, Upright; 2, semi-upright; 3, semi-spread; 4, spread; 5, prostrate |

| FC | 1, White background with pink veins; 2, white; 3, pink; 4, purplish red |

| SS | 1, Eagle-shaped; 2, sheep-shaped; 3, spherical |

| SCC | 1, Ivory white; 2, light brown; 3, beige; 4, brown; 5, reddish-brown; 6, black; 7, yellow; 8, beige |

| SSS | 1, Rough; 2, uneven; 3, smooth |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Su, J.; Li, W.; Xue, L.; Cai, X.; Li, T.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, J. Phenotypic Variability and Genetic Diversity Analysis of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Germplasm Resources. Plants 2026, 15, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010024

Zhang S, Su J, Li W, Xue L, Cai X, Li T, Xiao J, Zhang J. Phenotypic Variability and Genetic Diversity Analysis of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Germplasm Resources. Plants. 2026; 15(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shuping, Jundong Su, Wanming Li, Lili Xue, Xuefei Cai, Tingzhao Li, Jing Xiao, and Jinbo Zhang. 2026. "Phenotypic Variability and Genetic Diversity Analysis of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Germplasm Resources" Plants 15, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010024

APA StyleZhang, S., Su, J., Li, W., Xue, L., Cai, X., Li, T., Xiao, J., & Zhang, J. (2026). Phenotypic Variability and Genetic Diversity Analysis of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Germplasm Resources. Plants, 15(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010024