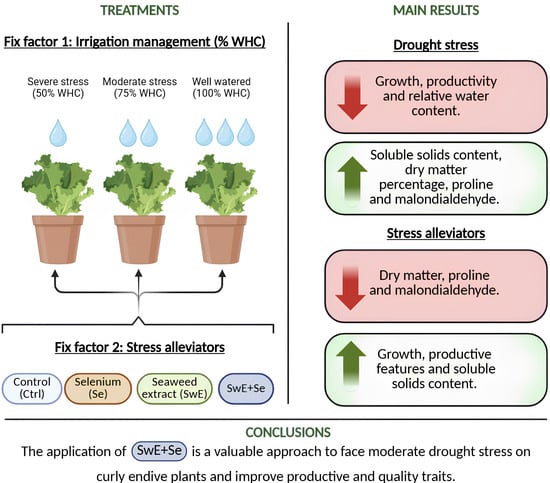

Selenium Biofortification and an Ecklonia maxima-Based Seaweed Extract Jointly Compose Curly Endive Drought Stress Tolerance in a Soilless System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Field Experiment and Plant Material

2.2. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

2.3. Substrate Water Retention Curve and Water Levels

2.4. Biostimulant and Selenium Treatments

2.5. Morphological, Physiological and Soluble Solid Content Measurements

2.6. Mineral Composition of Curly Endive

2.7. Leaf Relative Water Content and Malondialdehyde and Proline Concentrations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO Statistical Database. 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Ulas, F.; Kılıç, F.N.; Ulas, A. Alleviate the Influence of Drought Stress by Using Grafting Technology in Vegetable Crops: A Review. J. Crop Health 2025, 77, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jideani, A.I.; Silungwe, H.; Takalani, T.; Omolola, A.O.; Udeh, H.O.; Anyasi, T.A. Antioxidant-rich natural fruit and vegetable products and human health. Int. J. Food Prop. 2021, 24, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, L.; Ntatsi, G.; Iapichino, G.; D’Anna, F.; De Pasquale, C. Effect of Selenium Enrichment and Type of Application on Yield, Functional Quality and Mineral Composition of Curly Endive Grown in a Hydroponic System. Agronomy 2019, 9, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadio, G.; Bellone, M.L.; Mensitieri, F.; Parisi, V.; Santoro, V.; Vitiello, M.; Dal Piaz, F.; De Tommasi, N. Characterization of Health Beneficial Components in Discarded Leaves of Three Escarole (Cichorium endivia L.) Cultivar and Study of Their Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U.; Oba, S. Drought Stress Enhances Nutritional and Bioactive Compounds, Phenolic Acids and Antioxidant Capacity of Amaranthus Leafy Vegetable. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.F.; Huda, S.; Yong, M.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Chen, Z.-H.; Ahmed, T. Alleviation of Drought and Salt Stress in Vegetables: Crop Responses and Mitigation Strategies. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 99, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgio, D.; Cellini, A.; Donati, I.; Pastore, C.; Onofrietti, C.; Spinelli, F. Facing Climate Change: Application of Microbial Biostimulants to Mitigate Stress in Horticultural Crops. Agronomy 2020, 10, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yu, H.; Guan, X.; Wang, G.; Guo, R. Accelerated Dryland Expansion under Climate Change. Nature Clim. Change 2016, 6, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Rouphael, Y. Response and Defence Mechanisms of Vegetable Crops against Drought, Heat and Salinity Stress. Agriculture 2021, 11, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigit Tri Pamungkas, S.; Suwarto; Suprayogi; Farid, N. Drought Stress: Responses and Mechanism in Plants. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2022, 10, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Roychoudhury, A. Cold Stress and Photosynthesis. In Photosynthesis, Productivity and Environmental Stress; Ahmad, P., Ahanger, M.A., Alyemeni, M.N., Alam, P., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 27–37. ISBN 978-1-119-50177-0. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, J.; Wi, S.H.; Seo, T.C.; Moon, J.H.; Jang, S. Growing Vegetables in a Warming World—A Review of Crop Response to Drought Stress, and Strategies to Mitigate Adverse Effects in Vegetable Production. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1561100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Shen, Y.; Yang, W.; Pan, Q.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Li, B.; Zhang, L. Comparative Metabolic Study of Two Contrasting Chinese Cabbage Genotypes under Mild and Severe Drought Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rady, M.M.; Belal, H.E.E.; Gadallah, F.M.; Semida, W.M. Selenium Application in Two Methods Promotes Drought Tolerance in Solanum lycopersicum Plant by Inducing the Antioxidant Defense System. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 266, 109290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Kong, L.; Yu, X.; Ottosen, C.-O.; Zhao, T.; Jiang, F.; Wu, Z. Oxidative Damage and Antioxidant Mechanism in Tomatoes Responding to Drought and Heat Stress. Acta Physiol. Plant 2019, 41, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.K.; Bhandari, S.R.; Jo, J.S.; Song, J.W.; Lee, J.G. Effect of Drought Stress on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters, Phytochemical Contents, and Antioxidant Activities in Lettuce Seedlings. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, L.; Consentino, B.B.; Ntatsi, G.; La Bella, S.; Baldassano, S.; Rouphael, Y. Stand-Alone or Combinatorial Effects of Grafting and Microbial and Non-Microbial Derived Compounds on Vigour, Yield and Nutritive and Functional Quality of Greenhouse Eggplant. Plants 2022, 11, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consentino, B.B.; Vultaggio, L.; Sabatino, L.; Ntatsi, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Bondì, C.; De Pasquale, C.; Guarino, V.; Iacuzzi, N.; Capodici, G.; et al. Combined Effects of Biostimulants, N Level and Drought Stress on Yield, Quality and Physiology of Greenhouse-Grown Basil. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Van Gerrewey, T.; Geelen, D. A Meta-Analysis of Biostimulant Yield Effectiveness in Field Trials. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 836702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vasconcelos, A.C.F.; Chaves, L.H.G. Biostimulants and Their Role in Improving Plant Growth under Abiotic Stresses. In Biostimulants in Plant Science; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-83880-162-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sangha, J.S.; Kelloway, S.; Critchley, A.T.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweeds (Macroalgae) and Their Extracts as Contributors of Plant Productivity and Quality. In Advances in Botanical Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 71, pp. 189–219. ISBN 978-0-12-408062-1. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Leskovar, D.I. Effects of A. nodosum Seaweed Extracts on Spinach Growth, Physiology and Nutrition Value under Drought Stress. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 183, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campobenedetto, C.; Agliassa, C.; Mannino, G.; Vigliante, I.; Contartese, V.; Secchi, F.; Bertea, C.M. A Biostimulant Based on Seaweed (Ascophyllum nodosum and Laminaria digitata) and Yeast Extracts Mitigates Water Stress Effects on Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Agriculture 2021, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulant Properties of Seaweed Extracts in Plants: Implications towards Sustainable Crop Production. Plants 2021, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EL Boukhari, M.E.M.; Barakate, M.; Bouhia, Y.; Lyamlouli, K. Trends in Seaweed Extract Based Biostimulants: Manufacturing Process and Beneficial Effect on Soil-Plant Systems. Plants 2020, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titov, A.F.; Kaznina, N.M.; Karapetyan, T.A.; Dorshakova, N.V.; Tarasova, V.N. Role of Selenium in Plants, Animals, and Humans. Biol. Bull. Rev. 2022, 12, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Gupta, S. An Overview of Selenium Uptake, Metabolism, and Toxicity in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semida, W.M.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Abdelkhalik, A.; Hemida, K.A.; Abdurrahman, H.A.; Howladar, S.M.; Leilah, A.A.A.; Rady, M.O.A. Selenium Modulates Antioxidant Activity, Osmoprotectants, and Photosynthetic Efficiency of Onion under Saline Soil Conditions. Agronomy 2021, 11, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrypnik, L.; Feduraev, P.; Golovin, A.; Maslennikov, P.; Styran, T.; Antipina, M.; Riabova, A.; Katserov, D. The Integral Boosting Effect of Selenium on the Secondary Metabolism of Higher Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.; Cheema, M.A.; Sher, A.; Ijaz, M.; Ul-Allah, S.; Nawaz, A.; Abbas, T.; Ali, Q. Physiological and Biochemical Attributes of Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Seedlings Are Influenced by Foliar Application of Silicon and Selenium under Water Deficit. Acta Physiol. Plant 2019, 41, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, P.; Nasini, L.; Del Buono, D.; D’Amato, R.; Tedeschini, E.; Businelli, D. Selenium Protects Olive (Olea europaea L.) from Drought Stress. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 164, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.L.O.; de Oliveira, L.C.A.; Mendes, N.A.C.; Silva, V.M.; Vicente, E.F.; dos Reis, A.R. Selenium Increases Photosynthetic Pigments, Flavonoid Biosynthesis, Nodulation, and Growth of Soybean Plants (Glycine max L.). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 1397–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, C. Effects of Selenium on Leaf Traits and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Eggplant. Funct. Plant Biol. 2025, 52, FP24292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Leng, J.; Lei, X.; Wan, C.; Li, D.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, P.; Feng, B.; Gao, J. Effects of Selenium (Se) Uptake on Plant Growth and Yield in Common Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench). Field Crops Res. 2023, 302, 109070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Cui, H.; Li, H.; Qiang, X.; Han, Q.; Liu, H. Foliar Application of Selenium Enhances Drought Tolerance in Tomatoes by Modulating the Antioxidative System and Restoring Photosynthesis. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markoska, V.; Spalevic, V.; Lisichkov, K.; Atkovska, K.; Gulaboski, R. Determination of Water Retention Characteristics of Perlite and Peat. Agric. For. 2018, 64, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menberu, M.W.; Marttila, H.; Ronkanen, A.-K.; Haghighi, A.T.; Kløve, B. Hydraulic and Physical Properties of Managed and Intact Peatlands: Application of the Van Genuchten-Mualem Models to Peat Soils. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR028624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formisano, L.; Ciriello, M.; El-Nakhel, C.; De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y. Dataset on the Effects of Anti-Insect Nets of Different Porosity on Mineral and Organic Acids Profile of Cucurbita pepo L. Fruits and Leaves. Data 2021, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero, Z.; Madrid, Y.; Cámara, C. Selenium Species Bioaccessibility in Enriched Radish (Raphanus sativus): A Potential Dietary Source of Selenium. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2412–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, S.; Farieri, E.; Ferrante, A.; Romano, D. Physiological and Biochemical Responses in Two Ornamental Shrubs to Drought Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wan, S.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Z.; Qin, P. Leaf Chlorophyll Fluorescence, Hyperspectral Reflectance, Pigments Content, Malondialdehyde and Proline Accumulation Responses of Castor Bean (Ricinus communis L.) Seedlings to Salt Stress Levels. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, K.-J.; Zörb, C.; Geilfus, C.-M. Drought and Crop Yield. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Hussain, S.; Qadir, T.; Khaliq, A.; Ashraf, U.; Parveen, A.; Saqib, M.; Rafiq, M. Drought stress in plants: An overview on implications, tolerance mechanisms and agronomic mitigation strategies. Plant Sci. Today 2019, 6, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Karimi, M.; Venditti, A.; Zahra, N.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Farooq, M. Plant Adaptation to Drought Stress: The Role of Anatomical and Morphological Characteristics in Maintaining the Water Status. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xiao, C.; Qiu, T.; Deng, J.; Cheng, H.; Cong, X.; Cheng, S.; Rao, S.; Zhang, Y. Selenium Regulates Antioxidant, Photosynthesis, and Cell Permeability in Plants under Various Abiotic Stresses: A Review. Plants 2022, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, J.J.; Blasco, B.; Rosales, M.A.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, E.; Leyva, R.; Cervilla, L.M.; Romero, L.; Ruiz, J.M. Response of Nitrogen Metabolism in Lettuce Plants Subjected to Different Doses and Forms of Selenium: Response of Nitrogen Metabolism to Selenium in Lettuce. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1914–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.H.; Lei, B.; Cheng, R.F.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Yang, Q.C. Selenium distribution and nitrate metabolism in hydroponic lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.): Effects of selenium forms and light spectra. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, B.; Ashraf, K.; Abbasi, A.; Ali, H.M.; Sultan, K.; Munir, T.; Khan, M.T.; uz Zaman, Q. Effect of selenium on growth, physio-biochemical and yield traits of lettuce under limited water regimes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraghi Ardebili, Z.; Oraghi Ardebili, N.; Jalili, S.; Safiallah, S. The Modified Qualities of Basil Plants by Selenium and/or Ascorbic Acid. Turk. J. Bot. 2015, 39, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.I.; Kasinadhuni, N.; Arioli, T. The Effect of Seaweed Extract on Tomato Plant Growth, Productivity and Soil. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo Valencia, R.; Sánchez Acosta, L.; Fortis Hernández, M.; Preciado Rangel, P.; Gallegos Robles, M.Á.; Antonio Cruz, R.D.C.; Vázquez Vázquez, C. Effect of Seaweed Aqueous Extracts and Compost on Vegetative Growth, Yield, and Nutraceutical Quality of Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Fruit. Agronomy 2018, 8, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battacharyya, D.; Babgohari, M.Z.; Rathor, P.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed Extracts as Biostimulants in Horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babita, M.; Maheswari, M.; Rao, L.M.; Shanker, A.K.; Rao, D.G. Osmotic Adjustment, Drought Tolerance and Yield in Castor (Ricinus communis L.) Hybrids. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2010, 69, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Mirabad, A.; Lofti, M.; Roozban, M.R. Growth, Yield, Yield Components and Water-Use Efficiency in Irrigated Cantaloupes under Full and Deficit Irrigation. Electron. J. Biol. 2014, 10, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.Y. The Impact of Drought Stress on the Nutritional Quality of Vegetables. In Drought Stress; Chaudhry, U.K., Öztürk, Z.N., Gökçe, A.F., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 143–158. ISBN 978-3-031-80609-4. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Yan, H.; You, M.; Duan, J.; Chen, M.; Xing, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, X. Enhancing Drought Tolerance and Fruit Characteristics in Tomato through Exogenous Melatonin Application. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, D.; Pan, Q. Impact of Deficit Irrigation During Pre-Ripening Stages on Jujube (Ziziphus Jujube Mill.‘Jing39’) Fruit-Soluble Solids Content and Cracking. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawrylak-Nowak, B.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Matraszek-Gawron, R. Mechanisms of Selenium-Induced Enhancement of Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants. In Plant Nutrients and Abiotic Stress Tolerance; Hasanuzzaman, M., Fujita, M., Oku, H., Nahar, K., Hawrylak-Nowak, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 269–295. ISBN 978-981-10-9044-8. [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo, M.A.; de Melo, A.A.R.; Silva, V.M.; dos Reis, A.R. Selenium Enhances ROS Scavenging Systems and Sugar Metabolism Increasing Growth of Sugarcane Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 201, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, P.; Roosta, H.R.; Khodadadi, M.; Torkashvand, A.M.; Jahromi, M.G. Effects of Brown Seaweed Extract, Silicon, and Selenium on Fruit Quality and Yield of Tomato under Different Substrates. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Ullah, H.; Himanshu, S.K.; García-Caparrós, P.; Tisarum, R.; Cha-um, S.; Datta, A. Ascophyllum Nodosum Seaweed Extract and Potassium Alleviate Drought Damage in Tomato by Improving Plant Water Relations, Photosynthetic Performance, and Stomatal Function. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 2255–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Nanda, S.; Singh, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, D.; Singh, B.N.; Mukherjee, A. Seaweed Extracts: Enhancing Plant Resilience to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1457500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Turkyilmaz Unal, B.; García-Caparrós, P.; Khursheed, A.; Gul, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Osmoregulation and Its Actions during the Drought Stress in Plants. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1321–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhurwane, M.; Tóth, B.; Moloi, M.J. Effectiveness of Soil, Foliar, and Seed Selenium Applications in Modulating Physio-Biochemical, and Yield Responses to Drought Stress in Vegetable Soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill). Plants 2025, 14, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esringü, A.; Ekinci, M.; Tiraşci, S.; Turan, M.; Dursun, A.; Ercişli, S.; Yildirim, E. Selenium Supplementation Affects the Growth, Yield and Selenium Accumulation in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2015, 68, 801–810. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, A.; Corell, M.; Chivet, M.; Parrado, M.A.; Pardo, J.M.; Leidi, E.O. Reassessing the Role of Potassium in Tomato Grown with Water Shortages. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Cordones, M.; García-Sánchez, F.; Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Rubio, F.; Rosales, M.A. Coping with Water Shortage: An Update on the Role of K+, Cl−, and Water Membrane Transport Mechanisms on Drought Resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Xu, T.; Zhang, J.; Shen, K.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. Drought-Induced Responses of Nitrogen Metabolism in Ipomoea Batatas. Plants 2020, 9, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, Z.; Thounaojam, T.C.; Chowdhury, D.; Upadhyaya, H. The Role of Selenium and Nano Selenium on Physiological Responses in Plant: A Review. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 100, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, R.; Sarkar, A.; Dasgupta, D.; Acharya, K.; Keswani, C.; Popova, V.; Minkina, T.; Maksimov, A.Y.; Chakraborty, N. Unravelling the efficient applications of zinc and selenium for mitigation of abiotic stresses in plants. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarese, M.; Sourestani, M.; Quattrini, E.; Schiavi, M.; Ferrante, A. Biofortification of Spinach Plants APPLYING Selenium in the Nutrient Solution of Floating System. J. Fruit Ornam. Plant Res. 2012, 76, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccinelli, M.; Malorgio, F.; Pintimalli, L.; Rosellini, I.; Pezzarossa, B. Biofortification of Lettuce and Basil Seedlings to Produce Selenium Enriched Leafy Vegetables. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannachi, S.; Signore, A.; Adnan, M.; Mechi, L. Single and Associated Effects of Drought and Heat Stresses on Physiological, Biochemical and Antioxidant Machinery of Four Eggplant Cultivars. Plants 2022, 11, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Giordano, M.; Cardarelli, M.; Cozzolino, E.; Mori, M.; Kyriacou, M.; Bonini, P.; Colla, G. Plant- and Seaweed-Based Extracts Increase Yield but Differentially Modulate Nutritional Quality of Greenhouse Spinach through Biostimulant Action. Agronomy 2018, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, G.P.; Ntanasi, T.; Karavidas, I.; Marka, S.; Giannothanasis, E.; Vultaggio, L.; Gohari, G.; Sabatino, L.; Ntatsi, G. Enhancing Nutritional and Functional Properties of Hydroponically Grown Underutilised Leafy Greens Through Selenium Biofortification. Plants 2025, 14, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannico, A.; El-Nakhel, C.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Giordano, M.; Stazi, S.R.; De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y. Combating Micronutrient Deficiency and Enhancing Food Functional Quality Through Selenium Fortification of Select Lettuce Genotypes Grown in a Closed Soilless System. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatino, L.; Consentino, B.B.; Rouphael, Y.; Baldassano, S.; De Pasquale, C.; Ntatsi, G. Ecklonia Maxima-Derivate Seaweed Extract Supply as Mitigation Strategy to Alleviate Drought Stress in Chicory Plants. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 312, 111856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Jan, I.; Ullah, H.; Fahad, S.; Saud, S.; Adnan, M.; Ali, B.; Liu, K.; Harrison, M.T.; Hassan, H. Biochemical Response of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) to Selenium (Se) Under Drought Stress. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Xin, L.; Gao, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Effects of Foliar Selenium Application on Oxidative Damage and Photosynthetic Properties of Greenhouse Tomato under Drought Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziq, A.; Wang, Y.; Mohi Ud Din, A.; Sun, J.; Shu, S.; Guo, S. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Salt Tolerance in Tomato (Var. Ailsa Craig): Responses of Physiological and Transcriptional Changes in RBOH’s and ABA Biosynthesis and Signalling Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, T.M.; Mariotti, L.; De Pedro, L.F.; Guglielminetti, L.; Picciarelli, P.; Scartazza, A. Drought Induced Changes of Leaf-to-Root Relationships in Two Tomato Genotypes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 128, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanè, C.; Cosentino, S.L.; Romano, D.; Toscano, S. Relative Water Content, Proline, and Antioxidant Enzymes in Leaves of Long Shelf-Life Tomatoes under Drought Stress and Rewatering. Plants 2022, 11, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, M.G.D.B.; dos Reis, A.R. Roles of Selenium in Mineral Plant Nutrition: ROS Scavenging Responses against Abiotic Stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 164, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, O.; Quille, P.; O’Connell, S. Ascophyllum nodosum Extract Biostimulants and Their Role in Enhancing Tolerance to Drought Stress in Tomato Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 126, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Li, J.; Gong, B.; Lu, Y.; Wu, X.; Lü, G.; Gao, H. Drought Stress Tolerance in Vegetables: The Functional Role of Structural Features, Key Gene Pathways, and Exogenous Hormones. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desoky, E.-S.M.; Mansour, E.; Ali, M.M.A.; Yasin, M.A.T.; Abdul-Hamid, M.I.E.; Rady, M.M.; Ali, E.F. Exogenously Used 24-Epibrassinolide Promotes Drought Tolerance in Maize Hybrids by Improving Plant and Water Productivity in an Arid Environment. Plants 2021, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhad, M.S.; Majid, A.D.; Alireza, P.; Hossain, F.M. Variation in Yield and Biochemical Factors of German Chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) under Foliar Application of Osmolytes and Drought Stress Conditions. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 2019, 8, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucini, L.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Canaguier, R.; Kumar, P.; Colla, G. The Effect of a Plant-Derived Biostimulant on Metabolic Profiling and Crop Performance of Lettuce Grown under Saline Conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 182, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.E.A.; de Camargo e Castro, P.R.; Gaziola, S.A.; Azevedo, R.A. Is Seaweed Extract an Elicitor Compound? Changing Proline Content in Drought-Stressed Bean Plants. Comun. Sci. 2018, 9, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Fahadi Hoveizeh, N.; Kadkhodaei, S.; Vaculík, M. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Commercial Strawberry Cultivars under Optimal and Drought Stress Conditions. Plants 2023, 12, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, F.; Ahmad, R.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Waraich, E.A.; Khan, S.Z. Effect of Selenium Foliar Spray on Physiological and Biochemical Processes and Chemical Constituents of Wheat under Drought Stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 113, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Dry Matter Content (%) | K (g kg−1 dw) | N (g kg−1 dw) | P (g kg−1 dw) | Ca (g kg−1 dw) | Mg (g kg−1 dw) | S (g kg−1 dw) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | ||||||||||||||

| 50% WHC | 8.67 | a | 28.11 | a | 12.56 | a | 2.95 | a | 13.74 | a | 2.51 | a | 3.39 | a |

| 75% WHC | 8.06 | b | 28.49 | a | 13.37 | a | 3.18 | a | 14.29 | a | 2.68 | a | 3.45 | a |

| 100% WHC | 7.94 | b | 25.27 | b | 13.04 | a | 2.95 | a | 14.63 | a | 2.78 | a | 3.62 | a |

| T | ||||||||||||||

| Ctrl | 8.51 | a | 28.16 | a | 13.30 | a | 3.08 | a | 14.66 | a | 2.61 | a | 3.18 | a |

| Se | 7.93 | b | 28.80 | a | 13.51 | a | 2.95 | a | 14.62 | a | 2.76 | a | 3.84 | a |

| SwE | 8.11 | b | 26.00 | a | 12.58 | a | 2.97 | a | 13.36 | a | 2.57 | a | 3.43 | a |

| SwE + Se | 8.23 | b | 26.20 | a | 12.56 | a | 3.10 | a | 14.23 | a | 2.68 | a | 3.50 | a |

| Significance | ||||||||||||||

| I | ** | * | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |||||||

| T | * | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |||||||

| I × T | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Consentino, B.B.; Mancuso, F.; Vultaggio, L.; Bellitto, P.; Ntatsi, G.; Cannata, C.; La Placa, G.G.; Mauro, R.P.; La Bella, S.; Sabatino, L. Selenium Biofortification and an Ecklonia maxima-Based Seaweed Extract Jointly Compose Curly Endive Drought Stress Tolerance in a Soilless System. Plants 2026, 15, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010170

Consentino BB, Mancuso F, Vultaggio L, Bellitto P, Ntatsi G, Cannata C, La Placa GG, Mauro RP, La Bella S, Sabatino L. Selenium Biofortification and an Ecklonia maxima-Based Seaweed Extract Jointly Compose Curly Endive Drought Stress Tolerance in a Soilless System. Plants. 2026; 15(1):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010170

Chicago/Turabian StyleConsentino, Beppe Benedetto, Fabiana Mancuso, Lorena Vultaggio, Pietro Bellitto, Georgia Ntatsi, Claudio Cannata, Gaetano Giuseppe La Placa, Rosario Paolo Mauro, Salvatore La Bella, and Leo Sabatino. 2026. "Selenium Biofortification and an Ecklonia maxima-Based Seaweed Extract Jointly Compose Curly Endive Drought Stress Tolerance in a Soilless System" Plants 15, no. 1: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010170

APA StyleConsentino, B. B., Mancuso, F., Vultaggio, L., Bellitto, P., Ntatsi, G., Cannata, C., La Placa, G. G., Mauro, R. P., La Bella, S., & Sabatino, L. (2026). Selenium Biofortification and an Ecklonia maxima-Based Seaweed Extract Jointly Compose Curly Endive Drought Stress Tolerance in a Soilless System. Plants, 15(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010170