Molecular Mechanisms and Experimental Strategies for Understanding Plant Drought Response

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sensing and Signaling of Water Stress

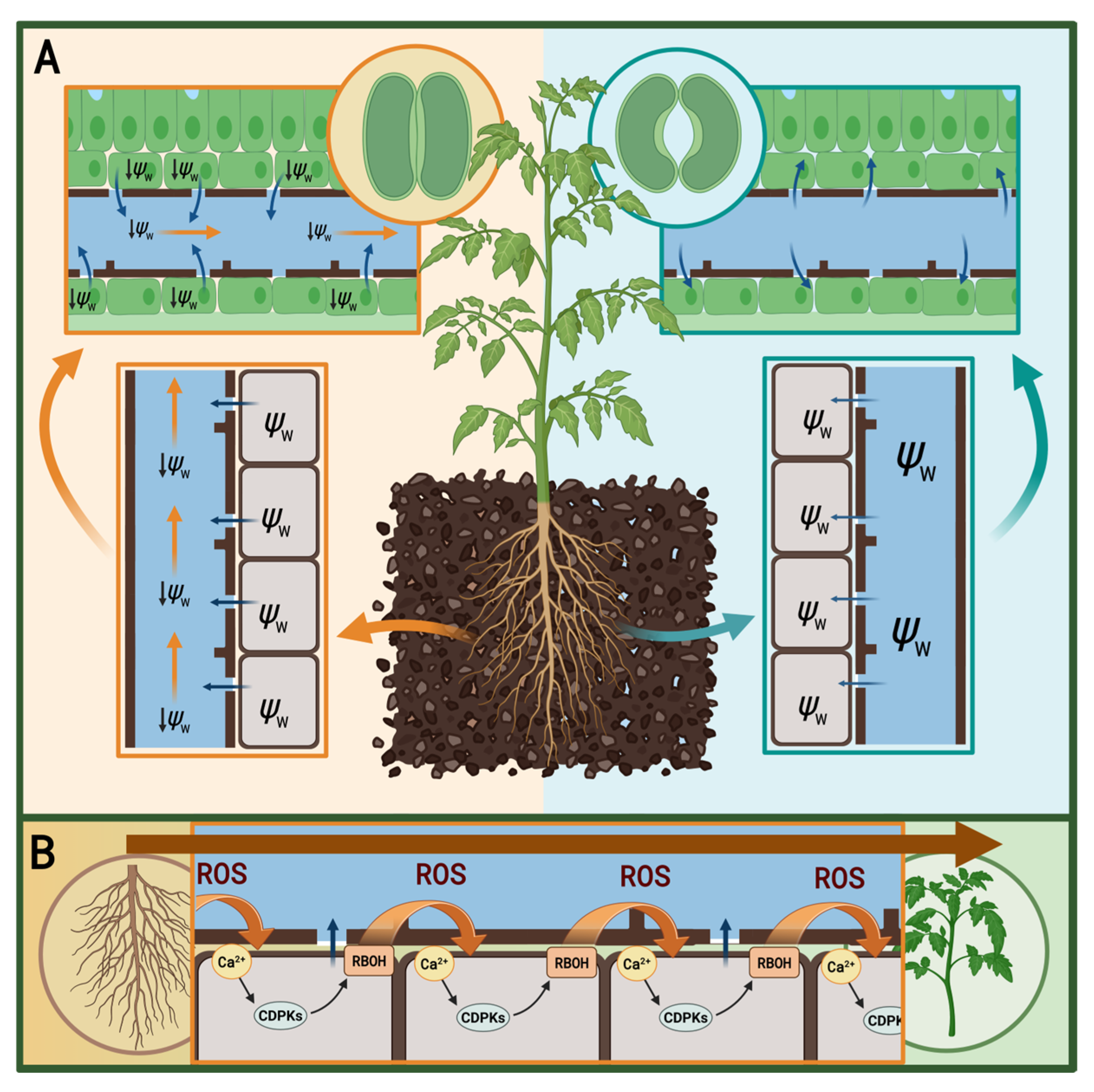

2.1. Local Sensing and Signaling Pathways

2.2. Propagation of Rapid Systemic Signals—Communication Between the Root and the Shoot

2.3. Phytohormonal Regulation of Drought Signaling

3. Key Transcription Factors in Drought Response

3.1. ABA-Dependent Pathway

3.2. ABA-Independent Pathway

3.3. Integration of ABA-Dependent and ABA-Independent Signals

4. Accumulation of Osmolytes and Cellular Protectants

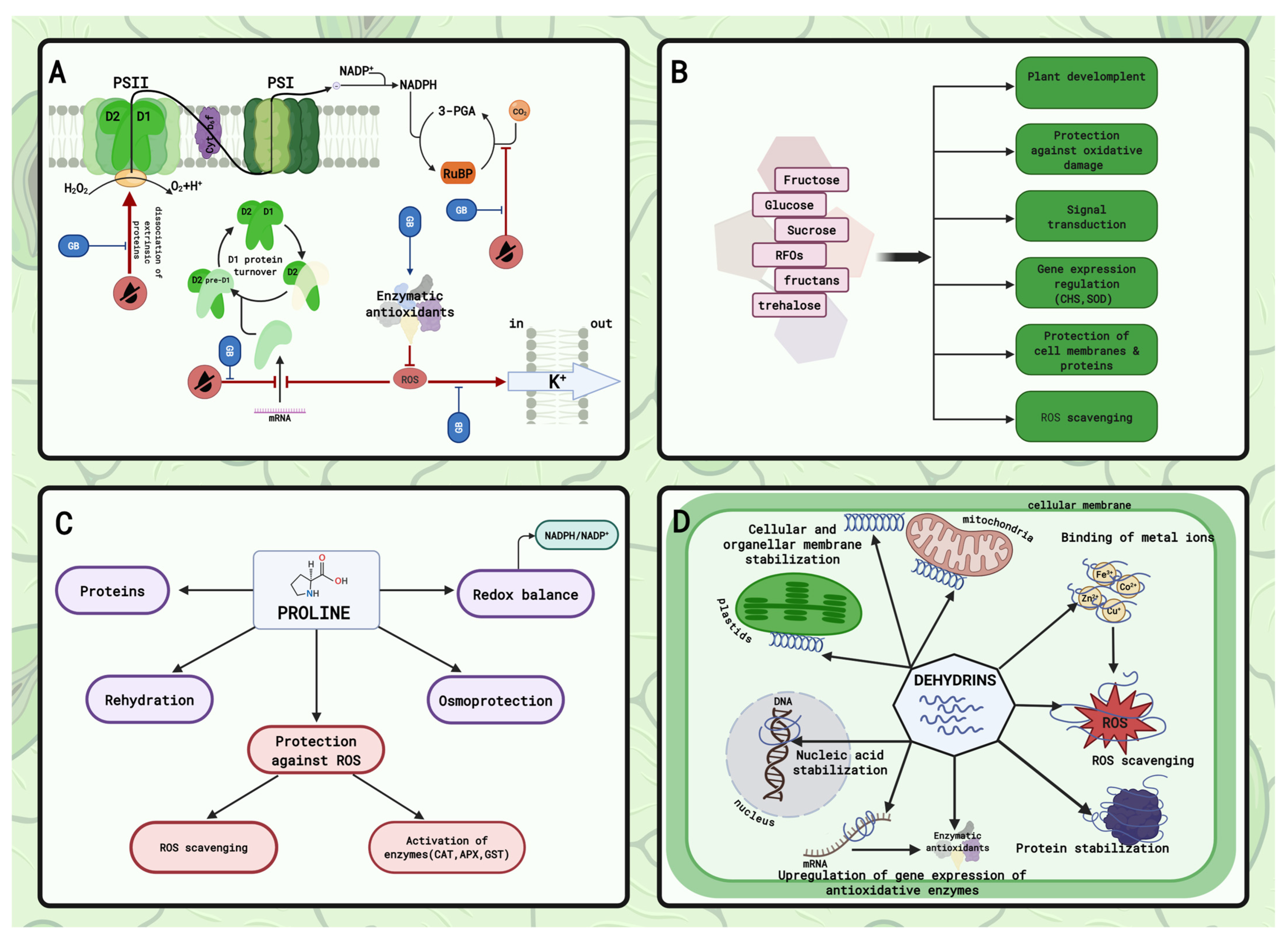

4.1. Ammonium Compounds

4.2. Sugars and Polyols

4.3. Amino Acids

4.4. Dehydrins—Cellular Protectants

4.5. Potassium Ions

5. ROS Generation and Effects of Oxidative Stress

5.1. Sites of ROS Production in Plants

5.2. ROS Signaling and Antioxidant Systems

5.2.1. Enzymatic Antioxidant System

5.2.2. Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant System

5.3. Methods for Studying Oxidative Stress in Plants

5.3.1. Indirect Methods

5.3.2. Direct Methods

6. Mechanisms of Cell Wall Remodeling and Growth Regulation

6.1. Cell Wall Mechanics in Expansion Growth

6.2. Remodeling of CW Architecture

6.2.1. Expansins

6.2.2. Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylases/Hydrolases

6.2.3. Pectins and Pectin Methylesterases

6.3. ABA and Auxin Interplay

6.4. Methodological Frameworks in Plant Water Status

6.4.1. Water Potential—Golden Standard Tools

6.4.2. A New Era of Measuring Water Potential

6.4.3. Osmotic Potential and Turgor Dynamics

7. Water Use Efficiency and Stomatal Regulation

7.1. Mechanisms Regulating Stomatal Aperture

7.2. Photosynthetic Limitations Caused by Closed Stomata

7.3. Evaluation of the Stress-Imposed Damage to the Photosynthetic Apparatus

7.3.1. Assessment of PSII Efficiency and Photoprotection Using PAM Fluorometry

7.3.2. Quantification of Photosynthetic Pigments and Anthocyanins

8. Integrating Multi-Omics and High-Throughput Phenotyping in Drought Research

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

- Accurately quantifying and standardizing drought severity on plants (e.g., by measuring soil water content or Ψw) to reflect realistic deficits, thereby ensuring translational validity of laboratory results. An alternative could be to use a liquid medium containing PolyEthylene Glycol (PEG); however, this method may not fully reflect the water stress that plants experience in nature.

- To enable valid comparisons across independent studies, the research framework should include a minimum set of crucial physiological parameters, such as leaf water potential, photosynthetic efficiency, oxidative stress parameters, and pigment analysis. This standardized baseline is essential for distinguishing the actual physiological status of a stressed plant.

- Categorizing the studied species or cultivars within established drought resistance strategies would enable the translation of research data into practical, useful information for other scientists and breeders.

- Functional redundancy within transcription factor families (e.g., WRKY, NAC, DREB) often masks the impact of single-gene modifications. Future research must incorporate multi-omics approach to map regulatory hubs, enabling simultaneous editing of multi-genes or trait stacking. Manipulating entire gene clusters is necessary to bypass redundancy and engineer robust drought resilience.

- In nature, drought stress rarely occurs in isolation. Therefore, experimental designs should consider realistic combinations of various factors, such as water scarcity, high irradiance, heat waves, and elevated atmospheric CO2 levels, projected over the coming decades, providing a comprehensive picture of the climatic relationships relevant to plant survival in future agroecosystems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought Stress Impacts on Plants and Different Approaches to Alleviate Its Adverse Effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesk, C.; Rowhani, P.; Ramankutty, N. Influence of Extreme Weather Disasters on Global Crop Production. Nature 2016, 529, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Romanello, M.; Walawender, M.; Hsu, S.C.; Moskeland, A.; Palmeiro-Silva, Y.; Scamman, D.; Ali, Z.; Ameli, N.; Angelova, D.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. The 2024 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Facing Record-Breaking Threats from Delayed Action. Lancet 2024, 404, 1847–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, R.; Schipper, E.L.F.; Ospina, D.; Mirazo, P.; Alencar, A.; Anvari, M.; Artaxo, P.; Biresselioglu, M.E.; Blome, T.; Boeckmann, M.; et al. Ten New Insights in Climate Science 2024. One Earth 2025, 8, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2025 Set to Be Second or Third Warmest Year on Record, Continuing Exceptionally High Warming Trend. Available online: https://wmo.int/media/news/2025-set-be-second-or-third-warmest-year-record-continuing-exceptionally-high-warming-trend (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Guastello, P.; Smith, K.H.; Knutson, C.; Svoboda, M.; Tsegai, D.; Diallo, B.L.; Acebal, J. Drought Hotspots Around the World 2023–2025; United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification: Bonn, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A.; Wang, Y.F.; Akbar, R.; Alhoqail, W.A. Mechanistic Insights and Future Perspectives of Drought Stress Management in Staple Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1547452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, A.T.; Momoh, M.E.; Oladipo, O.E.; Dada, O.O.; Amoo, A.A. Ethidium Bromide-Induced Genetic Variability and Drought Tolerance in Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) Under Field Conditions. J. Soil Plant Environ. 2025, 4, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balting, D.F.; AghaKouchak, A.; Lohmann, G.; Ionita, M. Northern Hemisphere Drought Risk in a Warming Climate. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 4, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Sheffield, J.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Funk, C.; Miralles, D.G.; Peng, J.; Dyer, E.; Talib, J.; Beck, H.E.; Singer, M.B.; et al. Warming Accelerates Global Drought Severity. Nature 2025, 642, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghpanah, M.; Hashemipetroudi, S.; Arzani, A.; Araniti, F. Drought Tolerance in Plants: Physiological and Molecular Responses. Plants 2024, 13, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavrukov, Y.; Kurishbayev, A.; Jatayev, S.; Shvidchenko, V.; Zotova, L.; Koekemoer, F.; De Groot, S.; Soole, K.; Langridge, P. Early Flowering as a Drought Escape Mechanism in Plants: How Can It Aid Wheat Production? Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 302418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The Physiology of Plant Responses to Drought. Science 2020, 368, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wu, B.; Wang, L.; Gao, Y. Multi-Scale Drought Resilience in Terrestrial Plants: From Molecular Mechanisms to Ecosystem Sustainability. Water 2025, 17, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Kuromori, T.; Urano, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Drought Stress Responses and Resistance in Plants: From Cellular Responses to Long-Distance Intercellular Communication. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 556972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, B.; Foyer, C.H.; Pandey, G.K. The Integration of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Calcium Signalling in Abiotic Stress Responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1985–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollist, H.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Sengupta, S.; Nuhkat, M.; Kangasjärvi, J.; Mittler, R. Rapid Responses to Abiotic Stress: Priming the Landscape for the Signal Transduction Network. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, P.; Manna, M.; Kaur, H.; Thakur, T.; Gandass, N.; Bhatt, D.; Muthamilarasan, M. Phytohormone Signaling and Crosstalk in Regulating Drought Stress Response in Plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1305–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, A.; Grill, E.; Huang, J. Hydraulic Signals in Long-Distance Signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013, 16, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taiz, L.; Møller, I.M.; Murphy, A.; Zeiger, E. Plant Physiology and Development; Oxford Univesity Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juenger, T.E.; Verslues, P.E. Time for a Drought Experiment: Do You Know Your Plants’ Water Status? Plant Cell 2023, 35, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Swaef, T.; Pieters, O.; Appeltans, S.; Borra-Serrano, I.; Coudron, W.; Couvreur, V.; Garre, S.; Lootens, P.; Nicolaï, B.; Pols, L.; et al. On the Pivotal Role of Water Potential to Model Plant Physiological Processes. Silico Plants 2022, 4, diab038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Water Dynamics|Learn Science at Scitable. Available online: https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/soil-water-dynamics-103089121/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Prieto, I.; Armas, C.; Pugnaire, F.I. Water Release through Plant Roots: New Insights into Its Consequences at the Plant and Ecosystem Level. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Song, X.; Mehra, P.; Yu, S.; Li, Q.; Tashenmaimaiti, D.; Bennett, M.; Kong, X.; Bhosale, R.; Huang, G. ABA-Auxin Cascade Regulates Crop Root Angle in Response to Drought. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 542–553.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohorn, B.D.; Kobayashi, M.; Johansen, S.; Riese, J.; Huang, L.F.; Koch, K.; Fu, S.; Dotson, A.; Byers, N. An Arabidopsis Cell Wall-Associated Kinase Required for Invertase Activity and Cell Growth. Plant J. 2006, 46, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Katagiri, T.; Shinozaki, K.; Qi, Z.; Tatsumi, H.; Furuichi, T.; Kishigami, A.; Sokabe, M.; Kojima, I.; Sato, S.; et al. Arabidopsis Plasma Membrane Protein Crucial for Ca2+ Influx and Touch Sensing in Roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3639–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haswell, E.S.; Peyronnet, R.; Barbier-Brygoo, H.; Meyerowitz, E.M.; Frachisse, J.M. Two MscS Homologs Provide Mechanosensitive Channel Activities in the Arabidopsis Root. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Wilson, M.E.; Richardson, R.A.; Haswell, E.S. Genetic and Physical Interactions between the Organellar Mechanosensitive Ion Channel Homologs MSL1, MSL2, and MSL3 Reveal a Role for Inter-organellar Communication in Plant Development. Plant Direct 2019, 3, e00124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, T.; Nakagawa, Y.; Mori, K.; Nakano, M.; Imamura, T.; Kataoka, H.; Terashima, A.; Iida, K.; Kojima, I.; Katagiri, T.; et al. MCA1 and MCA2 That Mediate Ca2+ Uptake Have Distinct and Overlapping Roles in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1284–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, A.; Ali, S.; Park, S.; Bae, H. Deciphering the Role of Mechanosensitive Channels in Plant Root Biology: Perception, Signaling, and Adaptive Responses. Planta 2023, 258, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Yang, H.; Xue, Y.; Kong, D.; Ye, R.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Theprungsirikul, L.; Shrift, T.; Krichilsky, B.; et al. OSCA1 Mediates Osmotic-Stress-Evoked Ca2+ Increases Vital for Osmosensing in Arabidopsis. Nature 2014, 514, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Zhang, P.; Lu, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wei, X.; Mei, F.; Wei, L.; et al. Systematic Analysis of the Maize OSCA Genes Revealing ZmOSCA Family Members Involved in Osmotic Stress and ZmOSCA2.4 Confers Enhanced Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toriyama, T.; Shinozawa, A.; Yasumura, Y.; Saruhashi, M.; Hiraide, M.; Ito, S.; Matsuura, H.; Kuwata, K.; Yoshida, M.; Baba, T.; et al. Sensor Histidine Kinases Mediate ABA and Osmostress Signaling in the Moss Physcomitrium patens. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 164–175.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monshausen, G.B.; Bibikova, T.N.; Weisenseel, M.H.; Gilroy, S. Ca2+ Regulates Reactive Oxygen Species Production and PH during Mechanosensing in Arabidopsis Roots. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2341–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubany-Mari, T.; Alegre-Batlle, L.; Jiang, K.; Feldman, L.J. Use of a Redox-Sensing GFP (c-RoGFP1) for Real-Time Monitoring of Cytosol Redox Status in Arabidopsis Thaliana Water-Stressed Plants. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Foyer, C.H. Intracellular Redox Compartmentation and ROS-Related Communication in Regulation and Signaling. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, F.K.; Rivero, R.M.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Reactive Oxygen Species, Abiotic Stress and Stress Combination. Plant J. 2017, 90, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Ohura, I.; Kawakita, K.; Yokota, N.; Fujiwara, M.; Shimamoto, K.; Doke, N.; Yoshioka, H. Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinases Regulate the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species by Potato NADPH Oxidase. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1065–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Miller, G.; Morales, J.; Shulaev, V.; Torres, M.A.; Mittler, R. Respiratory Burst Oxidases: The Engines of ROS Signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.J.; Wei, F.J.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.J.; Ratnasekera, D.; Liu, W.X.; Wu, W.H. Arabidopsis Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase CPK10 Functions in Abscisic Acid- and Ca2+-Mediated Stomatal Regulation in Response to Drought Stress. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1232–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Li, S.; Asim, M.; Mao, J.; Xu, D.; Ullah, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H. The Arabidopsis Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinases (CDPKs) and Their Roles in Plant Growth Regulation and Abiotic Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, S.; Seth, C.S.; Roychoudhury, A. The Molecular Paradigm of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) with Different Phytohormone Signaling Pathways during Drought Stress in Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, A.; Weiler, E.W.; Steudle, E.; Grill, E. A Hydraulic Signal in Root-to-Shoot Signalling of Water Shortage. Plant J. 2007, 52, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Chi, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, F.; Wan, D.; Ni, J.; Yuan, F.; Wu, X.; et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Sensor HPCA1 Is an LRR Receptor Kinase in Arabidopsis. Nature 2020, 578, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichman, Y.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Peck, S.; Luan, S.; Mittler, R. HPCA1 Is Required for Systemic Reactive Oxygen Species and Calcium Cell-to-Cell Signaling and Plant Acclimation to Stress. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 4453–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Cao, J.; Ge, K.; Li, L. The Site of Water Stress Governs the Pattern of ABA Synthesis and Transport in Peanut. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Sawada, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Okamoto, M.; Ikegami, K.; Koiwai, H.; Seo, M.; Toyomasu, T.; Mitsuhashi, W.; Shinozaki, K.; et al. Drought Induction of Arabidopsis 9-Cis-Epoxycarotenoid Dioxygenase Occurs in Vascular Parenchyma Cells. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1984–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H.; Takasaki, H.; Takahashi, F.; Suzuki, T.; Iuchi, S.; Mitsuda, N.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Ikeda, M.; Seo, M.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; et al. Arabidopsis thaliana NGATHA1 Transcription Factor Induces ABA Biosynthesis by Activating NCED3 Gene during Dehydration Stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11178–E11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombesi, S.; Nardini, A.; Frioni, T.; Soccolini, M.; Zadra, C.; Farinelli, D.; Poni, S.; Palliotti, A. Stomatal Closure Is Induced by Hydraulic Signals and Maintained by ABA in Drought-Stressed Grapevine. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, M.; Lado, J.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Zacariás, L.; Arbona, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A. Root ABA Accumulation in Long-Term Water-Stressed Plants Is Sustained by Hormone Transport from Aerial Organs. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 2457–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Liu, F. Exogenous Abscisic Acid Priming Modulates Water Relation Responses of Two Tomato Genotypes With Contrasting Endogenous Abscisic Acid Levels to Progressive Soil Drying Under Elevated CO2. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 733658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Lyu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ye, N. Effects of Stress-Induced ABA on Root Architecture Development: Positive and Negative Actions. Crop. J. 2023, 11, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, J.; Dupeux, F.; Betz, K.; Antoni, R.; Gonzalez-Guzman, M.; Rodriguez, L.; Márquez, J.A.; Rodriguez, P.L. Structural Insights into PYR/PYL/RCAR ABA Receptors and PP2Cs. Plant Sci. 2012, 182, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakawa, T.; Fujita, Y.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Tanokura, M. Structure and Function of Abscisic Acid Receptors. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh, H.; Qamer, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, A. The Multifaceted Roles of PP2C Phosphatases in Plant Growth, Signaling, and Responses to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, T.; Sugiyama, N.; Takahashi, F.; Anderson, J.C.; Ishihama, Y.; Peck, S.C.; Shinozaki, K. Genetics and Phosphoproteomics Reveal a Protein Phosphorylation Network in the Abscisic Acid Signaling Pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, rs8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Niu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W. Signaling Transduction of ABA, ROS, and Ca2+ in Plant Stomatal Closure in Response to Drought. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.K.; Dubeaux, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Schroeder, J.I. Signaling Mechanisms in Abscisic Acid-Mediated Stomatal Closure. Plant J. 2021, 105, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imes, D.; Mumm, P.; Böhm, J.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.S.; Marten, I.; Geiger, D.; Hedrich, R. Open Stomata 1 (OST1) Kinase Controls R-Type Anion Channel QUAC1 in Arabidopsis Guard Cells. Plant J. 2013, 74, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcheska, F.; Ahmad, A.; Batool, S.; Müller, H.M.; Ludwig-Müller, J.; Kreuzwieser, J.; Randewig, D.; Hänsch, R.; Mendel, R.R.; Hell, R.; et al. Drought-Enhanced Xylem Sap Sulfate Closes Stomata by Affecting ALMT12 and Guard Cell ABA Synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 798–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, M.; Shen, J.; Chen, D.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W. ZmOST1 Mediates Abscisic Acid Regulation of Guard Cell Ion Channels and Drought Stress Responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2019, 61, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Nakashima, K.; Yoshida, T.; Katagiri, T.; Kidokoro, S.; Kanamori, N.; Umezawa, T.; Fujita, M.; Maruyama, K.; Ishiyama, K.; et al. Three SnRK2 Protein Kinases Are the Main Positive Regulators of Abscisic Acid Signaling in Response to Water Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 2123–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Fujita, Y.; Maruyama, K.; Mogami, J.; Todaka, D.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Four Arabidopsis AREB/ABF Transcription Factors Function Predominantly in Gene Expression Downstream of SnRK2 Kinases in Abscisic Acid Signalling in Response to Osmotic Stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, F.; Suzuki, T.; Osakabe, Y.; Betsuyaku, S.; Kondo, Y.; Dohmae, N.; Fukuda, H.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. A Small Peptide Modulates Stomatal Control via Abscisic Acid in Long-Distance Signalling. Nature 2018, 556, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zhu, Q.; Qin, P.; Yu, L.; Li, W.; Sun, H. The Peptide-Encoding CLE25 Gene Modulates Drought Response in Cotton. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wei, J.; Tian, Y. Dual Roles of SmCLE25 Peptide in Regulating Stresses Response and Leaf Senescence. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.P.; Sussmilch, F.; Nichols, D.S.; Cardoso, A.A.; Brodribb, T.J.; McAdam, S.A.M. Leaves, Not Roots or Floral Tissue, Are the Main Site of Rapid, External Pressure-Induced ABA Biosynthesis in Angiosperms. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, D.H.; Pridgeon, A.J.; Hetherington, A.M. How Arabidopsis Talks to Itself about Its Water Supply. Mol. Cell 2018, 70, 991–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; He, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F. Comparative Proteomics Illustrates the Complexity of Drought Resistance Mechanisms in Two Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Cultivars under Dehydration and Rehydration. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogawat, A.; Yadav, B.; Chhaya; Lakra, N.; Singh, A.K.; Narayan, O.P. Crosstalk between Phytohormones and Secondary Metabolites in the Drought Stress Tolerance of Crop Plants: A Review. Physiol. Plant 2021, 172, 1106–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hou, L.; Meng, J.; You, H.; Li, Z.; Gong, Z.; Yang, S.; Shi, Y. The Antagonistic Action of Abscisic Acid and Cytokinin Signaling Mediates Drought Stress Response in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 970–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, A.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Van Ha, C.; Zheng, B.; Bhardwaj, M.; Tran, L.S.P. Roles of Abscisic Acid and Auxin in Plants during Drought: A Molecular Point of View. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 204, 108129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, Z.; Smoljan, A.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Friml, J. Foraging for Water by MIZ1-Mediated Antagonism between Root Gravitropism and Hydrotropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2427315122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, J.; Zheng, S.; Liu, C.; Shen, J.; Li, J.; Li, L. OsREM4.1 Interacts with OsSERK1 to Coordinate the Interlinking between Abscisic Acid and Brassinosteroid Signaling in Rice. Dev. Cell 2016, 38, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.; Shang, Y.; Nam, K.H. Brassinosteroids Modulate ABA-Induced Stomatal Closure in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 6297–6308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, Y.M.; Shang, Y.; Yang, D.; Nam, K.H. Brassinosteroid Reduces ABA Accumulation Leading to the Inhibition of ABA-Induced Stomatal Closure. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 504, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravifar, F.; Mohammadi, M.; Eghlima, G. Brassinosteroids Improve Drought Resistance in Zinnia by Regulating Antioxidant Activity and Hormonal Interactions with ABA and Salicylic Acid. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 105, 2259–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, T.; Kolla, V.A.; Wang, C.Q.; Nasafi, Z.; Hicks, D.R.; Phadungchob, B.; Chehab, W.E.; Brandizzi, F.; Froehlich, J.; Dehesh, K. Functional Convergence of Oxylipin and Abscisic Acid Pathways Controls Stomatal Closure in Response to Drought. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qin, Y.; Liu, M.; Niu, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. The JASMONATE ZIM-Domain-OPEN STOMATA1 Cascade Integrates Jasmonic Acid and Abscisic Acid Signaling to Regulate Drought Tolerance by Mediating Stomatal Closure in Poplar. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ollas, C.; Arbona, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A. Jasmonoyl Isoleucine Accumulation Is Needed for Abscisic Acid Build-up in Roots of Arabidopsis under Water Stress Conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 2157–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Xie, J.; Huang, M.; Cai, J.; Zhou, Q.; Dai, T.; Jiang, D. Abscisic Acid and Jasmonic Acid Are Involved in Drought Priming-Induced Tolerance to Drought in Wheat. Crop. J. 2021, 9, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, I.; Vitali, M.; Ferrero, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ruyter-Spira, C.; Novák, O.; Strnad, M.; Lovisolo, C.; Schubert, A.; Cardinale, F. Low Levels of Strigolactones in Roots as a Component of the Systemic Signal of Drought Stress in Tomato. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ha, C.; Leyva-Gonzalez, M.A.; Osakabe, Y.; Tran, U.T.; Nishiyama, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Seki, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Dong, N.V.; et al. Positive Regulatory Role of Strigolactone in Plant Responses to Drought and Salt Stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tan, D.X.; Liang, D.; Chang, C.; Jia, D.; Ma, F. Melatonin Mediates the Regulation of ABA Metabolism, Free-Radical Scavenging, and Stomatal Behaviour in Two Malus Species under Drought Stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Wang, J.; Xu, D.; Tao, S.; Chong, S.; Yan, D.; Li, Z.; Yuan, H.; Zheng, B. Melatonin Regulates the Functional Components of Photosynthesis, Antioxidant System, Gene Expression, and Metabolic Pathways to Induce Drought Resistance in Grafted Carya Cathayensis Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandurska, H. Drought Stress Responses: Coping Strategy and Resistance. Plants 2022, 11, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardieu, F.; Simonneau, T.; Muller, B. The Physiological Basis of Drought Tolerance in Crop Plants: A Scenario-Dependent Probabilistic Approach. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 733–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallé, Á.; Csiszár, J.; Benyó, D.; Laskay, G.; Leviczky, T.; Erdei, L.; Tari, I. Isohydric and Anisohydric Strategies of Wheat Genotypes under Osmotic Stress: Biosynthesis and Function of ABA in Stress Responses. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Maldini, C.; Acevedo, M.; Estay, D.; Aros, F.; Dumroese, R.K.; Sandoval, S.; Pinto, M. Examining Physiological, Water Relations, and Hydraulic Vulnerability Traits to Determine Anisohydric and Isohydric Behavior in Almond (Prunus dulcis) Cultivars: Implications for Selecting Agronomic Cultivars under Changing Climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 974050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyemaobi, O.; Sangma, H.; Garg, G.; Wallace, X.; Kleven, S.; Suwanchaikasem, P.; Roessner, U.; Dolferus, R. Reproductive Stage Drought Tolerance in Wheat: Importance of Stomatal Conductance and Plant Growth Regulators. Genes 2021, 12, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, K.; Stavreva, D.A.; Upadhyaya, A.; Hager, G.L. Transcription Factor Dynamics: One Molecule at a Time. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 39, 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Tian, F.; Yang, D.C.; Meng, Y.Q.; Kong, L.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. PlantTFDB 4.0: Toward a Central Hub for Transcription Factors and Regulatory Interactions in Plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D1040–D1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Shen, X. Regulatory Network Established by Transcription Factors Transmits Drought Stress Signals in Plant. Stress Biol. 2022, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Fujita, Y.; Sayama, H.; Kidokoro, S.; Maruyama, K.; Mizoi, J.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. AREB1, AREB2, and ABF3 Are Master Transcription Factors That Cooperatively Regulate ABRE-Dependent ABA Signaling Involved in Drought Stress Tolerance and Require ABA for Full Activation. Plant J. 2010, 61, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, A.; Daszkowska-Golec, A.; Szarejko, I. Updates on the Role of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) and ABSCISIC ACID-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTORs (ABFs) in ABA Signaling in Different Developmental Stages in Plants. Cells 2021, 10, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Jiang, M.; Xu, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Gou, L.; Pi, E. Regulation Mechanisms of Plant Basic Leucine Zippers to Various Abiotic Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 561913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimotho, R.N.; Baillo, E.H.; Zhang, Z. Transcription Factors Involved in Abiotic Stress Responses in Maize (Zea mays L.) and Their Roles in Enhanced Productivity in the Post Genomics Era. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.H.; Li, C.W.; Su, R.C.; Cheng, C.P.; Sanjaya; Tsai, Y.C.; Chan, M.T. A Tomato BZIP Transcription Factor, SlAREB, Is Involved in Water Deficit and Salt Stress Response. Planta 2010, 231, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Meng, X.; Cai, J.; Li, G.; Dong, T.; Li, Z. Basic Leucine Zipper Transcription Factor SlbZIP1 Mediates Salt and Drought Stress Tolerance in Tomato. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. VlbZIP30 of Grapevine Functions in Dehydration Tolerance via the Abscisic Acid Core Signaling Pathway. Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Wang, X.; Feng, T.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Gao, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Expression of a Grape (Vitis vinifera) BZIP Transcription Factor, VlbZIP36, in Arabidopsis thaliana Confers Tolerance of Drought Stress during Seed Germination and Seedling Establishment. Plant Sci. 2016, 252, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chu, J.; Ma, C.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xiong, J.; Cheng, Z.M. Overexpression of an ABA-Dependent Grapevine BZIP Transcription Factor, VvABF2, Enhances Osmotic Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldoni, E.; Genga, A.; Cominelli, E. Plant MYB Transcription Factors: Their Role in Drought Response Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 15811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wei, H.; Wang, K.; Tang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Si, H. MYB Transcription Factors: Acting as Molecular Switches to Regulate Different Signaling Pathways to Modulate Plant Responses to Drought Stress. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 226, 120676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Li, S.; An, X.; Liu, X.; Qin, H.; Wang, D. Transgenic Expression of MYB15 Confers Enhanced Sensitivity to Abscisic Acid and Improved Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Genet. Genom. 2009, 36, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Tang, M.; Wang, M.; Yu, Y.; Ruan, B. Advances in Understanding Drought Stress Responses in Rice: Molecular Mechanisms of ABA Signaling and Breeding Prospects. Genes 2024, 15, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, R.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Tian, Y.; Chen, T.; Li, J.; Jiao, F.; Jia, T.; Li, Y.; et al. ZmMYB56 Regulates Stomatal Closure and Drought Tolerance in Maize Seedlings through the Transcriptional Regulation of ZmTOM7. New Crops 2024, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, M.; Tian, Y.; He, W.; Han, L.; Xia, G. Over-Expression of TaMYB33 Encoding a Novel Wheat MYB Transcription Factor Increases Salt and Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 7183–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhang, F.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, D.; Li, K.; Chang, J.; Yang, G.; et al. A Wheat R2R3-Type MYB Transcription Factor TaODORANT1 Positively Regulates Drought and Salt Stress Responses in Transgenic Tobacco Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 260621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Li, L.; Wei, A.; Zhou, L.; Wang, B.; Liu, M.; Lei, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, X. TaMYB44-5A Reduces Drought Tolerance by Repressing Transcription of TaRD22-3A in the Abscisic Acid Signaling Pathway. Planta 2024, 260, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, V.; Parrotta, L.; Romi, M.; Del Duca, S.; Cai, G. Tomato Biodiversity and Drought Tolerance: A Multilevel Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Song, Q.; Miao, M.; Fan, T.; Tang, X. The 1R-MYB Transcription Factor SlMYB1L Modulates Drought Tolerance via an ABA-Dependent Pathway in Tomato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 222, 109721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, P.; Gao, Z.; Long, T.; Xing, C.; Li, J.; Xue, J.; Chen, G.; Xie, Q.; Hu, Z. Silencing of SlMYB78-like Reduces the Tolerance to Drought and Salt Stress via the ABA Pathway in Tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Quan, R.; Chen, G.; Yu, G.; Li, X.; Han, Z.; Xu, W.; Li, G.; Shi, J.; Li, B. An R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor VyMYB24, Isolated from Wild Grape Vitis yanshanesis J. X. Chen., Regulates the Plant Development and Confers the Tolerance to Drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 966641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Wang, Z.; Su, L.; Gong, L.; Xin, H. Vitis Myb14 Confer Cold and Drought Tolerance by Activating Lipid Transfer Protein Genes Expression and Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenge. Gene 2024, 890, 147792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Laxmi, A. Transcriptional Regulation of Drought Response: A Tortuous Network of Transcriptional Factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 165462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, P. The DREB Transcription Factor, a Biomacromolecule, Responds to Abiotic Stress by Regulating the Expression of Stress-Related Genes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 243, 125231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Nolan, T.; Jiang, H.; Tang, B.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Yin, Y. The AP2/ERF Transcription Factor TINY Modulates Brassinosteroid-Regulated Plant Growth and Drought Responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, G.; Manimaran, P.; Voleti, S.R.; Subrahmanyam, D.; Sundaram, R.M.; Bansal, K.C.; Viraktamath, B.C.; Balachandran, S.M. Stress-Inducible Expression of AtDREB1A Transcription Factor Greatly Improves Drought Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Indica Rice. Transgenic Res. 2014, 23, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanbhro, N.; Wang, H.J.; Yang, H.; Xu, X.J.; Jakhar, A.M.; Shalmani, A.; Zhang, R.X.; Bakhsh, Q.; Akbar, G.; Jakhro, M.I.; et al. Revisiting the Molecular Mechanisms and Adaptive Strategies Associated with Drought Stress Tolerance in Common Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, H.; Munir, F.; Amir, R.; Gul, A. Genome-Wide Identification, Comprehensive Characterization of Transcription Factors, Cis-Regulatory Elements, Protein Homology, and Protein Interaction Network of DREB Gene Family in Solanum lycopersicum. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1031679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; He, H.; Chang, Y.; Miao, B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Dong, F.; Xiong, L. Multiple Roles of NAC Transcription Factors in Plant Development and Stress Responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 510–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, L.S.P.; Nakashima, K.; Sakuma, Y.; Simpson, S.D.; Fujita, Y.; Maruyama, K.; Fujita, M.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Isolation and Functional Analysis of Arabidopsis Stress-Inducible NAC Transcription Factors That Bind to a Drought-Responsive Cis-Element in the Early Responsive to Dehydration Stress 1 Promoter. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, H.; Liu, S.; Tang, B.; Chen, J.; Xie, Z.; Nolan, T.M.; Jiang, H.; Guo, H.; Lin, H.Y.; Li, L.; et al. RD26 Mediates Crosstalk between Drought and Brassinosteroid Signalling Pathways. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.K.; Lindemose, S.; de Masi, F.; Reimer, J.J.; Nielsen, M.; Perera, V.; Workman, C.T.; Turck, F.; Grant, M.R.; Mundy, J.; et al. ATAF1 Transcription Factor Directly Regulates Abscisic Acid Biosynthetic Gene NCED3 in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Open Bio 2013, 3, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Wani, S.H.; Singh, B.; Bohra, A.; Dar, Z.A.; Lone, A.A.; Pareek, A.; Singla-Pareek, S.L. Transcription Factors and Plants Response to Drought Stress: Current Understanding and Future Directions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 204078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.K.; Chung, P.J.; Jeong, J.S.; Jang, G.; Bang, S.W.; Jung, H.; Kim, Y.S.; Ha, S.H.; Choi, Y.D.; Kim, J.K. The Rice OsNAC6 Transcription Factor Orchestrates Multiple Molecular Mechanisms Involving Root Structural Adaptions and Nicotianamine Biosynthesis for Drought Tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Li, J.; Tran, L.S.P.; Qin, F. A Transposable Element in a NAC Gene Is Associated with Drought Tolerance in Maize Seedlings. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, S.; Liu, M.; Mu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xuan, Y.; Niu, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W. Transcription Factor ZmNAC20 Improves Drought Resistance by Promoting Stomatal Closure and Activating Expression of Stress-Responsive Genes in Maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.-J.; Han, D.-J.; Zheng, W.-J.; Kang, Z.-S. Functional Characterization of TaNAC6-3B: A Key Regulator of Drought Tolerance in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229, 110578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Shao, Q.; Lu, Q.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, Q. Research Progress on Function of NAC Transcription Factors in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Euphytica 2023, 219, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, W.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, T.; Cao, H.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Q.; Xu, C.; Li, Z. SlNAC6, A NAC Transcription Factor, Is Involved in Drought Stress Response and Reproductive Process in Tomato. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 264, 153483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, C.; Shao, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, A.; Yu, J.; Shi, K. Transcriptomic and Genetic Approaches Reveal an Essential Role of the NAC Transcription Factor SlNAP1 in the Growth and Defense Response of Tomato. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Hong, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Song, F. Tomato NAC Transcription Factor SlSRN1 Positively Regulates Defense Response against Biotic Stress but Negatively Regulates Abiotic Stress Response. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.-L.; Wang, W.-N.; Nan, Q.; Liu, J.-W.; Ju, Y.-L.; Fang, Y.-L. VvNAC17, a Grape NAC Transcription Factor, Regulates Plant Response to Drought-Tolerance and Anthocyanin Synthesis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 219, 109379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X.; Ma, X.; Ayiguzeli, M.; Zhong, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.; Yadav, V.; Wu, X.; et al. VvNAC33 Functions as a Key Regulator of Drought Tolerance in Grapevine by Modulating Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 224, 109971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Liang, G.; Yu, D. Activated Expression of WRKY57 Confers Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, D. Activated Expression of AtWRKY53 Negatively Regulates Drought Tolerance by Mediating Stomatal Movement. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Q.; Hong, X.; Zhu, J.K.; Gong, Z. ABO3, a WRKY Transcription Factor, Mediates Plant Responses to Abscisic Acid and Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010, 63, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, S.; Ye, N.; Jiang, M.; Cao, J.; Zhang, J. WRKY Transcription Factors in Plant Responses to Stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2017, 59, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoso, M.A.; Hussain, A.; Ritonga, F.N.; Ali, Q.; Channa, M.M.; Alshegaihi, R.M.; Meng, Q.; Ali, M.; Zaman, W.; Brohi, R.D.; et al. WRKY Transcription Factors (TFs): Molecular Switches to Regulate Drought, Temperature, and Salinity Stresses in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1039329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineri, J.; Wang, S.; Peleg, Z.; Blumwald, E.; Chan, R.L. The Rice Transcription Factor OsWRKY47 Is a Positive Regulator of the Response to Water Deficit Stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015, 88, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Wu, T.; Ma, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Bian, M.; Bai, H.; Jiang, W.; Du, X. Rice Transcription Factor Oswrky55 Is Involved in the Drought Response and Regulation of Plant Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, P.; Zhao, J. Transcription Factors as Molecular Switches to Regulate Drought Adaptation in Maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.H.; Xu, J.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Liu, J.M.; Li, P.S.; Chen, M.; Ma, Y.Z.; Xu, Z.S. Drought-Responsive WRKY Transcription Factor Genes TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33 from Wheat Confer Drought and/or Heat Resistance in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Qiao, L.; Guo, H.; Guo, L.; Ren, F.; Bai, J.; Wang, Y. Genome-Wide Identification of Wheat WRKY Gene Family Reveals That TaWRKY75-A Is Referred to Drought and Salt Resistances. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 663118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Rong, X.; Sun, J.; Sun, T.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Feng, Y.; Chai, R.; et al. Expression of TaWRKY44, a Wheat WRKY Gene, in Transgenic Tobacco Confers Multiple Abiotic Stress Tolerances. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Song, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, N.; Yu, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, H.; Guo, S.; Bu, Y.; et al. The Wheat WRKY Transcription Factor TaWRKY1-2D Confers Drought Resistance in Transgenic Arabidopsis and Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 226, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, M.; Luo, W.; Ge, M.; Guan, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, W.; Lv, J. A Group I WRKY Gene, TaWRKY133, Negatively Regulates Drought Resistance in Transgenic Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Lv, L.; Duan, L.; Wu, J.; Shao, Q.; Li, X.; Lu, Q. A WRKY Transcription Factor, SlWRKY75, Positively Regulates Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Resistance to Ralstonia Solanacearum. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1704937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, L.; Liang, X.; Shen, Q. SlWRKY75 Functions as a Differential Regulator to Enhance Drought Tolerance in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 227, 110189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.F.; Liu, J.K.; Yang, F.M.; Zhang, G.Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Ou, Y.B.; Yao, Y.A. The WRKY Transcription Factor WRKY8 Promotes Resistance to Pathogen Infection and Mediates Drought and Salt Stress Tolerance in Solanum lycopersicum. Physiol. Plant 2020, 168, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, D.H.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, M.C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.H. The Tomato WRKY Transcription Factor SlWRKY17 Positively Regulates Drought Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Tobacco Plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 69, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, G.J.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, G.; Wan, H.; Cheng, Y. Tomato WRKY81 Acts as a Negative Regulator for Drought Tolerance by Modulating Guard Cell H2O2–Mediated Stomatal Closure. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 171, 103960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, R.; Wang, Y.; Guo, C.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Gao, H.; Wang, X. Over-Expression of a Grape WRKY Transcription Factor Gene, VlWRKY48, in Arabidopsis Thaliana Increases Disease Resistance and Drought Stress Tolerance. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2018, 132, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Ye, X.; Zheng, X.; Tan, B.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Feng, J. Overexpressing VvWRKY18 from Grapevine Reduces the Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis by Increasing Leaf Stomatal Density. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 275, 153741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Fan, X.; Hao, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. Negative Regulation by Transcription Factor VvWRKY13 in Drought Stress of Vitis vinifera L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Kuromori, T.; Sato, H.; Shinozaki, K. Regulatory Gene Networks in Drought Stress Responses and Resistance in Plants. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1081, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Pivotal Role of the AREB/ABF-SnRK2 Pathway in ABRE-Mediated Transcription in Response to Osmotic Stress in Plants. Physiol. Plant 2013, 147, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L.; Zhong, Y. Structure, Evolution, and Roles of MYB Transcription Factors Proteins in Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Pathways and Abiotic Stresses Responses in Plants: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1626844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.S.; Pandey, S.; Li, S.; Gookin, T.E.; Zhao, Z.; Albert, R.; Assmann, S.M. Common and Unique Elements of the ABA-Regulated Transcriptome of Arabidopsis Guard Cells. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kasuga, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Abe, H.; Miura, S.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Two Transcription Factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA Binding Domain Separate Two Cellular Signal Transduction Pathways in Drought- and Low-Temperature-Responsive Gene Expression, Respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1391–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Mizoi, J.; Kidokoro, S.; Maruyama, K.; Nakajima, J.; Nakashima, K.; Mitsuda, N.; Takiguchi, Y.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Kondou, Y.; et al. Arabidopsis GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR7 Functions as a Transcriptional Repressor of Abscisic Acid– and Osmotic Stress–Responsive Genes, Including DREB2A. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3393–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, F.; Sakuma, Y.; Tran, L.S.P.; Maruyama, K.; Kidokoro, S.; Fujita, Y.; Fujita, M.; Umezawa, T.; Sawano, Y.; Miyazono, K.I.; et al. Arabidopsis DREB2A-Interacting Proteins Function as RING E3 Ligases and Negatively Regulate Plant Drought Stress–Responsive Gene Expression. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1693–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Mizoi, J.; Yoshida, T.; Fujita, Y.; Nakajima, J.; Ohori, T.; Todaka, D.; Nakashima, K.; Hirayama, T.; Shinozaki, K.; et al. An ABRE Promoter Sequence Is Involved in Osmotic Stress-Responsive Expression of the DREB2A Gene, Which Encodes a Transcription Factor Regulating Drought-Inducible Genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 52, 2136–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xia, P. NAC Transcription Factors as Biological Macromolecules Responded to Abiotic Stress: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçarlı, C. Drought Stress and the Role of NAC Transcription Factors in Drought Response. In Drought Stress: Review and Recommendation; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xia, P. WRKY Transcription Factors: Key Regulators in Plant Drought Tolerance. Plant Sci. 2025, 359, 112647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, Z.; Shi, X.; Duan, W.; Fu, X.; Liu, J.; Guo, C.; Xiao, K. Transcription Factor Gene TaWRKY76 Confers Plants Improved Drought and Salt Tolerance through Modulating Stress Defensive-Associated Processes in Triticum aestivum L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 216, 109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, H.; Wang, H.; Tang, X. NAC Transcription Factors in Plant Multiple Abiotic Stress Responses: Progress and Prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 156056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Valencia, G.; Palomar, M.; Covarrubias, A.A.; Reyes, J.L. The Legume MiR1514a Modulates a NAC Transcription Factor Transcript to Trigger PhasiRNA Formation in Response to Drought. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2013–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Zhou, L.; Chen, W.; Ye, N.; Xia, J.; Zhuang, C. Overexpression of a MicroRNA-Targeted NAC Transcription Factor Improves Drought and Salt Tolerance in Rice via ABA-Mediated Pathways. Rice 2019, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Machinery in Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, J.; Singh, S.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Roles of Osmoprotectants in Improving Salinity and Drought Tolerance in Plants: A Review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shahzad, B.; Kumar, V.; Kohli, S.K.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Bali, A.S.; Handa, N.; Kapoor, D.; Bhardwaj, R.; Zheng, B. Phytohormones Regulate Accumulation of Osmolytes Under Abiotic Stress. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, F.; Akram, N.A.; Ashraf, M. Osmoprotection in Plants under Abiotic Stresses: New Insights into a Classical Phenomenon. Planta 2019, 251, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zuo, T.; Ni, W. Important Roles of Glycinebetaine in Stabilizing the Structure and Function of the Photosystem II Complex under Abiotic Stresses. Planta 2020, 251, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarin, A.; Ghosh, U.K.; Hossain, M.d.S.; Mahmud, A.; Khan, M.d.A.R. Glycine Betaine in Plant Responses and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, F.; Alyafei, M.; Hayat, F.; Al-Zayadneh, W.; El-Keblawy, A.; Sulieman, S.; Sheteiwy, M.S. Deciphering the Role of Glycine Betaine in Enhancing Plant Performance and Defense Mechanisms against Environmental Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1582332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, U.K.; Islam, M.N.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Khan, M.A.R. Understanding the Roles of Osmolytes for Acclimatizing Plants to Changing Environment: A Review of Potential Mechanism. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1913306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Ende, W.; Valluru, R. Sucrose, Sucrosyl Oligosaccharides, and Oxidative Stress: Scavenging and Salvaging? J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couée, I.; Sulmon, C.; Gouesbet, G.; El Amrani, A. Involvement of Soluble Sugars in Reactive Oxygen Species Balance and Responses to Oxidative Stress in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.E. Carbohydrate-Modulated Gene Expression in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1996, 47, 509–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincha, D.K.; Zuther, E.; Hellwege, E.M.; Heyer, A.G. Specific Effects of Fructo- and Gluco-Oligosaccharides in the Preservation of Liposomes during Drying. Glycobiology 2002, 12, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, J.H. Trehalose As a “Chemical Chaperone”. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007, 594, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Goswami, L.; Sangma, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Mukherjee, R.; Roy, N.; Basak, P.; Majumder, A.L. Manipulation of Inositol Metabolism for Improved Plant Survival under Stress: A “Network Engineering Approach”. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 21, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyro, H.W.; Ahmad, P.; Geissler, N. Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants: An Overview. In Environmental Adaptations and Stress Tolerance of Plants in the Era of Climate Change; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Rejeb, K.; Lefebvre-De Vos, D.; Le Disquet, I.; Leprince, A.S.; Bordenave, M.; Maldiney, R.; Jdey, A.; Abdelly, C.; Savouré, A. Hydrogen Peroxide Produced by NADPH Oxidases Increases Proline Accumulation during Salt or Mannitol Stress in Arabidopsis Thaliana. New Phytol. 2015, 208, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlachtowska, Z.; Rurek, M. Plant Dehydrins and Dehydrin-like Proteins: Characterization and Participation in Abiotic Stress Response. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1213188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, A.S. Protein Disorder in Plant Stress Adaptation: From Late Embryogenesis Abundant to Other Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graether, S.P.; Boddington, K.F. Disorder and Function: A Review of the Dehydrin Protein Family. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tompa, P.; Szász, C.; Buday, L. Structural Disorder Throws New Light on Moonlighting. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005, 30, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z. Plant Dehydrins: Expression, Regulatory Networks, and Protective Roles in Plants Challenged by Abiotic Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riyazuddin, R.; Nisha, N.; Singh, K.; Verma, R.; Gupta, R. Involvement of Dehydrin Proteins in Mitigating the Negative Effects of Drought Stress in Plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 41, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet, J.M.; Porcel, R.; Yenush, L. Modulation of Potassium Transport to Increase Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 5989–6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyo, Y.J.; Gierth, M.; Schroeder, J.I.; Cho, M.H. High-Affinity K(+) Transport in Arabidopsis: AtHAK5 and AKT1 Are Vital for Seedling Establishment and Postgermination Growth under Low-Potassium Conditions. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, H.; Fu, S.M.; Ge, H.M.; Tang, R.J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.H.; Zhang, H.X. Na+/H+ and K+/H+ Antiporters AtNHX1 and AtNHX3 from Arabidopsis Improve Salt and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Poplar. Biol. Plant 2017, 61, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, N.; Suo, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L. Genome-Wide Identification and Drought Stress-Induced Expression Analysis of the NHX Gene Family in Potato. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1396375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzebisz, W.; Gransee, A.; Szczepaniak, W.; Diatta, J. The Effects of Potassium Fertilization on Water-Use Efficiency in Crop Plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2013, 176, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.A.; Koutroubas, S.D. Potassium Supply for Improvement of Cereals Growth under Drought: A Review. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 3368–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Nahar, K.; Hossain, M.S.; Al Mahmud, J.; Hossen, M.S.; Masud, A.A.C.; Moumita; Fujita, M. Potassium: A Vital Regulator of Plant Responses and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses. Agronomy 2018, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I.; Rengel, Z. Humboldt Review: Potassium May Mitigate Drought Stress by Increasing Stem Carbohydrates and Their Mobilization into Grains. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 303, 154325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostofa, M.G.; Rahman, M.M.; Ghosh, T.K.; Kabir, A.H.; Abdelrahman, M.; Rahman Khan, M.A.; Mochida, K.; Tran, L.S.P. Potassium in Plant Physiological Adaptation to Abiotic Stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 186, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Reactive Species and Antioxidants. Redox Biology Is a Fundamental Theme of Aerobic Life. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Al Mahmud, J.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Abiotic Stress: Revisiting the Crucial Role of a Universal Defense Regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.; Shiade, S.R.G.; Saleem, A.; Shohani, F.; Fazeli, A.; Riaz, A.; Zulfiqar, U.; Shabaan, M.; Ahmed, I.; Rahimi, M. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Antioxidant Systems in Enhancing Plant Resilience Against Abiotic Stress. Int. J. Agron. 2025, 2025, 8834883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janku, M.; Luhová, L.; Petrivalský, M. On the Origin and Fate of Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Cell Compartments. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asada, K. Production and Scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species in Chloroplasts and Their Functions. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, B.B.; Hideg, É.; Krieger-Liszkay, A. Production, Detection, and Signaling of Singlet Oxygen in Photosynthetic Organisms. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 2145–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Mhamdi, A.; Foyer, C.H. The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Metabolism in Drought: Not So Cut and Dried. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Van Aken, O.; Schwarzländer, M.; Belt, K.; Millar, A.H. The Roles of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in Cellular Signaling and Stress Response in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanlerberghe, G.C. Alternative Oxidase: A Mitochondrial Respiratory Pathway to Maintain Metabolic and Signaling Homeostasis during Abiotic and Biotic Stress in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 6805–6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Suzuki, N.; Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Mittler, R. Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis and Signalling during Drought and Salinity Stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Sodmergen, T.; Han, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. An Endoplasmic Reticulum Response Pathway Mediates Programmed Cell Death of Root Tip Induced by Water Stress in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Chen, J.P.; Wang, X.W.; Li, P. Reactive Oxygen Species in Plants: Metabolism, Signaling, and Oxidative Modifications. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.A.; Daudi, A.; Butt, V.S.; Bolwell, G.P. Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Role in Plant Defence and Cell Wall Metabolism. Planta 2012, 236, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Liu, W.C.; Han, C.; Wang, S.; Bai, M.Y.; Song, C.P. Reactive Oxygen Species: Multidimensional Regulators of Plant Adaptation to Abiotic Stress and Development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 330–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienert, G.P.; Møller, A.L.B.; Kristiansen, K.A.; Schulz, A.; Møller, I.M.; Schjoerring, J.K.; Jahn, T.P. Specific Aquaporins Facilitate the Diffusion of Hydrogen Peroxide across Membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Schoebel, S.; Schmitz, F.; Dong, H.; Hedfalk, K. Characterization of Aquaporin-Driven Hydrogen Peroxide Transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Černý, M.; Habánová, H.; Berka, M.; Luklová, M.; Brzobohatý, B. Hydrogen Peroxide: Its Role in Plant Biology and Crosstalk with Signalling Networks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Schlauch, K.; Tam, R.; Cortes, D.; Torres, M.A.; Shulaev, V.; Dangl, J.L.; Mittler, R. The Plant NADPH Oxidase RBOHD Mediates Rapid Systemic Signaling in Response to Diverse Stimuli. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, ra45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubiella, U.; Seybold, H.; Durian, G.; Komander, E.; Lassig, R.; Witte, C.P.; Schulze, W.X.; Romeis, T. Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase/NADPH Oxidase Activation Circuit Is Required for Rapid Defense Signal Propagation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8744–8749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, S.; Suzuki, N.; Miller, G.; Choi, W.G.; Toyota, M.; Devireddy, A.R.; Mittler, R. A Tidal Wave of Signals: Calcium and ROS at the Forefront of Rapid Systemic Signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Anjum, N.A.; Gill, R.; Yadav, S.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M.; Mishra, P.; Sabat, S.C.; Tuteja, N. Superoxide Dismutase—Mentor of Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 10375–10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz De Carvalho, M.H. Drought Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Jiang, C.; Chen, L.; Paul, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Shen, G. Achieving Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants through Antioxidative Defense Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohagheghian, B.; Saeidi, G.; Arzani, A. Phenolic Compounds, Antioxidant Enzymes, and Oxidative Stress in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Genotypes under Field Drought-Stress Conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Mañogil, C.; Martínez-Melgarejo, P.A.; Martínez-García, P.; Rubio, M.; Hernández, J.A.; Barba-Espín, G.; Diaz-Vivancos, P.; Martínez-García, P.J. Comprehensive Study of the Hormonal, Enzymatic and Osmoregulatory Response to Drought in Prunus Species. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 326, 112786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Wang, F.; Luo, B.; Li, A.; Wang, C.; Shabala, L.; Ahmed, H.A.I.; Deng, S.; Zhang, H.; Song, P.; et al. Antioxidant Enzymatic Activity and Osmotic Adjustment as Components of the Drought Tolerance Mechanism in Carex duriuscula. Plants 2021, 10, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminario, A.; Song, L.; Zulet, A.; Nguyen, H.T.; González, E.M.; Larrainzar, E. Drought Stress Causes a Reduction in the Biosynthesis of Ascorbic Acid in Soybean Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 264600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñuelas, J.; Munné-Bosch, S. Isoprenoids: An Evolutionary Pool for Photoprotection. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hix, L.M.; Lockwood, S.F.; Bertram, J.S. Bioactive Carotenoids: Potent Antioxidants and Regulators of Gene Expression. Redox Rep. 2004, 9, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agati, G.; Azzarello, E.; Pollastri, S.; Tattini, M. Flavonoids as Antioxidants in Plants: Location and Functional Significance. Plant Sci. 2012, 196, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.H.B.; Cordella, C.B.Y.; Duarte-Sierra, A. Advances in Reactive Oxygen Species Detection across Biological Systems with Relevance to Postharvest Research. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 353, 114485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Khan, M.S.; Smith, E.N.; Flashman, E. Measuring ROS and Redox Markers in Plant Cells. RSC Chem. Biol. 2021, 2, 1384–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.E.; Postiglione, A.E.; Muday, G.K. Reactive Oxygen Species Function as Signaling Molecules in Controlling Plant Development and Hormonal Responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 69, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkidasamy, B.; Karthikeyan, M.; Ramalingam, S. Methods/Protocols for Determination of Oxidative Stress in Crop Plants. In Reactive Oxygen, Nitrogen and Sulfur Species in Plants: Production, Metabolism, Signaling and Defense Mechanisms; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Morishita, H.; Urano, K.; Shiozaki, N.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Yoshiba, Y. Effects of Free Proline Accumulation in Petunias under Drought Stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1975–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.P.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, F.; Luo, Y.; Wang, W. Overaccumulation of Glycine Betaine Enhances Tolerance to Drought and Heat Stress in Wheat Leaves in the Protection of Photosynthesis. Photosynthetica 2010, 48, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P.; Abdelbacki, A.M.M.; Albaqami, M.; Jan, R.; Kim, K.M. Proline Promotes Drought Tolerance in Maize. Biology 2025, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, H.M.; Casu, R.E.; Fletcher, A.T.; Schmidt, S.; Xu, J.; Maclean, D.J.; Manners, J.M.; Bonnett, G.D. Identification of Drought-Response Genes and a Study of Their Expression during Sucrose Accumulation and Water Deficit in Sugarcane Culms. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.N.; Khan, M.A.; Kang, S.M.; Hamayun, M.; Lee, I.J. Enhancement of Drought-Stress Tolerance of Brassica oleracea Var. italica L. by Newly Isolated Variovorax sp. YNA59. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 1500–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowtham, H.G.; Singh, B.; Murali, M.; Shilpa, N.; Prasad, M.; Aiyaz, M.; Amruthesh, K.N.; Niranjana, S.R. Induction of Drought Tolerance in Tomato upon the Application of ACC Deaminase Producing Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacterium Bacillus subtilis Rhizo SF 48. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 234, 126422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.J.; Lim, L.H.; Cheong, M.S.; Baek, D.; Park, M.S.; Cho, H.M.; Lee, S.H.; Jin, B.J.; No, D.H.; Cha, Y.J.; et al. Arabidopsis Ccoaomt1 Plays a Role in Drought Stress Response via Ros- and Aba-dependent Manners. Plants 2021, 10, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.W. Pepper SBP-Box Transcription Factor, CaSBP13, Plays a Negatively Role in Drought Response. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1412685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Seo, H.U.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, C.S. Physio-Biochemical and Molecular Characterization of a Rice Drought-Insensitive TILLING Line 1 (Ditl1) Mutant. Physiol. Plant 2022, 174, e13718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Wu, T.; Pei, T.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Xu, X. Overexpression of SlGATA17 Promotes Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Tomato Plants by Enhancing Activation of the Phenylpropanoid Biosynthetic Pathway. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 634888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, E.E.; Fairweather, S.J.; Vo, H.M.; Zhao, C.; Breakspear, A.; Kimura, S.; Carmody, M.; Wrzaczek, M.; Bröer, S.; Faulkner, C.; et al. SAL1-PAP Retrograde Signaling Orchestrates Photosynthetic and Extracellular Reactive Oxygen Species for Stress Responses. Plant J. 2025, 122, e70271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Fluhr, R. Singlet Oxygen Plays an Essential Role in the Root’s Response to Osmotic Stress. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzländer, M.; Fricker, M.D.; Sweetlove, L.J. Monitoring the in Vivo Redox State of Plant Mitochondria: Effect of Respiratory Inhibitors, Abiotic Stress and Assessment of Recovery from Oxidative Challenge. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2009, 1787, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Villasante, C.; Burén, S.; Blázquez-Castro, A.; Barón-Sola, Á.; Hernández, L.E. Fluorescent in Vivo Imaging of Reactive Oxygen Species and Redox Potential in Plants. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 122, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nietzel, T.; Elsässer, M.; Ruberti, C.; Steinbeck, J.; Ugalde, J.M.; Fuchs, P.; Wagner, S.; Ostermann, L.; Moseler, A.; Lemke, P.; et al. The Fluorescent Protein Sensor RoGFP2-Orp1 Monitors in Vivo H2O2 and Thiol Redox Integration and Elucidates Intracellular H2O2 Dynamics during Elicitor-Induced Oxidative Burst in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 1649–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dopp, I.J.; Kalac, K.; Mackenzie, S.A. Hydrogen Peroxide Sensor HyPer7 Illuminates Tissue-Specific Plastid Redox Dynamics. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exposito-Rodriguez, M.; Laissue, P.P.; Yvon-Durocher, G.; Smirnoff, N.; Mullineaux, P.M. Photosynthesis-Dependent H2O2 Transfer from Chloroplasts to Nuclei Provides a High-Light Signalling Mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Drago, I.; Behera, S.; Zottini, M.; Pizzo, P.; Schroeder, J.I.; Pozzan, T.; Schiavo, F.L. H2O2 in Plant Peroxisomes: An in Vivo Analysis Uncovers a Ca2+-Dependent Scavenging System. Plant J. 2010, 62, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, O.; Reshetnyak, G.; Grondin, A.; Saijo, Y.; Leonhardt, N.; Maurel, C.; Verdoucq, L. Aquaporins Facilitate Hydrogen Peroxide Entry into Guard Cells to Mediate ABA- and Pathogen-Triggered Stomatal Closure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9200–9205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, Z.; Lampl, N.; Meyer, A.J.; Zelinger, E.; Hipsch, M.; Rosenwasser, S. Resolving Diurnal Dynamics of the Chloroplastic Glutathione Redox State in Arabidopsis Reveals Its Photosynthetically Derived Oxidation. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 1828–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichman, Y.; Mittler, R. A Systemic Whole-Plant Change in Redox Levels Accompanies the Rapid Systemic Response to Wounding. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipsch, M.; Lampl, N.; Zelinger, E.; Barda, O.; Waiger, D.; Rosenwasser, S. Sensing Stress Responses in Potato with Whole-Plant Redox Imaging. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Plant Cell Wall Loosening by Expansins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 40, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Cheddadi, I.; Landrein, B.; Long, Y. Revisiting the Relationship between Turgor Pressure and Plant Cell Growth. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.L.; Steppe, K.; Cuny, H.E.; De Pauw, D.J.W.; Frank, D.C.; Schaub, M.; Rathgeber, C.B.K.; Cabon, A.; Fonti, P. Turgor—A Limiting Factor for Radial Growth in Mature Conifers along an Elevational Gradient. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Zhou, Z.; Cui, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zenda, T.; Wenjing, L. Advanced Imaging-Enabled Understanding of Cell Wall Remodeling Mechanisms Mediating Plant Drought Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1635078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voothuluru, P.; Wu, Y.; Sharp, R.E. Not so Hidden Anymore: Advances and Challenges in Understanding Root Growth under Water Deficits. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, F.S.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Lima, L.L.; Mesquita, R.O.; Carpinetti, P.A.; Machado, J.P.B.; Vital, C.E.; Vidigal, P.M.; Ramos, M.E.S.; Maximiano, M.R.; et al. Remodeling of the Cell Wall as a Drought-Tolerance Mechanism of a Soybean Genotype Revealed by Global Gene Expression Analysis. aBIOTECH 2021, 2, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, D.J.; Sorek, N. Plant Cell Wall Extensibility: Connecting Plant Cell Growth with Cell Wall Structure, Mechanics, and the Action of Wall-Modifying Enzymes. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lynch, J.P. Reduced Crown Root Number Improves Water Acquisition under Water Deficit Stress in Maize (Zea mays L.). J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 4545–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Peng, Y.; Xu, W. Crop Root Responses to Drought Stress: Molecular Mechanisms, Nutrient Regulations, and Interactions with Microorganisms in the Rhizosphere. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, D.; Chen, P.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Xie, Y.; Niu, C.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X.; et al. MdMYB88 and MdMYB124 Enhance Drought Tolerance by Modulating Root Vessels and Cell Walls in Apple. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 1296–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantó-Pastor, A.; Kajala, K.; Shaar-Moshe, L.; Manzano, C.; Timilsena, P.; De Bellis, D.; Gray, S.; Holbein, J.; Yang, H.; Mohammad, S.; et al. A Suberized Exodermis Is Required for Tomato Drought Tolerance. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.S.; Islam, A. Plant Cell Wall Hydration and Plant Physiology: An Exploration of the Consequences of Direct Effects of Water Deficit on the Plant Cell Wall. Plants 2021, 10, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacete, L.; Schulz, J.; Engelsdorf, T.; Bartosova, Z.; Vaahtera, L.; Yan, G.; Gerhold, J.M.; Ticha, T.; Øvstebø, C.; Gigli-Bisceglia, N.; et al. THESEUS1 Modulates Cell Wall Stiffness and Abscisic Acid Production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2119258119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Pedetti, M.B.; Rauschert, I.; Sainz, M.M.; Amorim-Silva, V.; Botella, M.A.; Borsani, O.; Sotelo-Silveira, M. The Arabidopsis TETRATRICOPEPTIDE THIOREDOXIN-LIKE 1 Gene Is Involved in Anisotropic Root Growth during Osmotic Stress Adaptation. Genes 2021, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruszka, M. Solutions for a Local Equation of Anisotropic Plant Cell Growth: An Analytical Study of Expansin Activity. J. R. Soc. Interface 2011, 8, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, F.B.; Chen, Y.; Bozorg, B.; Clough, J.; Jönsson, H.; Braybrook, S.A. Anisotropic Growth Is Achieved through the Additive Mechanical Effect of Material Anisotropy and Elastic Asymmetry. eLife 2018, 7, e38161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Plant Expansins: Diversity and Interactions with Plant Cell Walls. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 25, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Han, Y.; Meng, Z.; Zhou, S.; Xiangzhu, K.; Wei, W. Overexpression of the Wheat Expansin Gene TaEXPA2 Improved Seed Production and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Tobacco Plants. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hao, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L. Expression of Two α-Type Expansins from Ammopiptanthus nanus in Arabidopsis thaliana Enhance Tolerance to Cold and Drought Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwin Narayan, J.; Chakravarthi, M.; Nerkar, G.; Manoj, V.M.; Dharshini, S.; Subramonian, N.; Premachandran, M.N.; Arun Kumar, R.; Krishna Surendar, K.; Hemaprabha, G.; et al. Overexpression of Expansin EaEXPA1, a Cell Wall Loosening Protein Enhances Drought Tolerance in Sugarcane. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 159, 113035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebli, Y.; Geitmann, A. Cellular Growth in Plants Requires Regulation of Cell Wall Biochemistry. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017, 44, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratilová, B.; Kozmon, S.; Stratilová, E.; Hrmova, M. Plant Xyloglucan Xyloglucosyl Transferases and the Cell Wall Structure: Subtle but Significant. Molecules 2020, 25, 5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklöf, J.M.; Brumer, H. The XTH Gene Family: An Update on Enzyme Structure, Function, and Phylogeny in Xyloglucan Remodeling. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.Z.; Zhu, X.F.; Miller, J.G.; Gregson, T.; Zheng, S.J.; Fry, S.C. Distinct Catalytic Capacities of Two Aluminium-Repressed Arabidopsis thaliana Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase/Hydrolases, XTH15 and XTH31, Heterologously Produced in Pichia. Phytochemistry 2015, 112, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franková, L.; Fry, S.C. Biochemistry and Physiological Roles of Enzymes That ‘Cut and Paste’ Plant Cell-Wall Polysaccharides. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3519–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrmova, M.; Farkas, V.; Lahnstein, J.; Fincher, G.B. A Barley Xyloglucan Xyloglucosyl Transferase Covalently Links Xyloglucan, Cellulosic Substrates, and (1,3;1,4)-β-D-Glucans. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 12951–12962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iurlaro, A.; De Caroli, M.; Sabella, E.; De Pascali, M.; Rampino, P.; De Bellis, L.; Perrotta, C.; Dalessandro, G.; Piro, G.; Fry, S.C.; et al. Drought and Heat Differentially Affect XTH Expression and XET Activity and Action in 3-Day-Old Seedlings of Durum Wheat Cultivars with Different Stress Susceptibility. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.; Yao, F.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, H.; Sun, S.; Jiang, C.; An, Y.; Chen, N.; Huang, L.; Lu, M.; et al. Identification of the Xyloglucan Endotransglycosylase/Hydrolase Genes and the Role of PagXTH12 in Drought Resistance in Poplar. For. Res. 2024, 4, e039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M.; Guo, X.; Zhang, R.; Luo, K.; Chen, Y. The XTH Gene Family in Cassava: Genomic Characterization, Evolutionary Dynamics, and Functional Roles in Abiotic Stress and Hormonal Response. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braybrook, S.A.; Hofte, H.; Peaucelle, A. Probing the Mechanical Contributions of the Pectin Matrix: Insights for Cell Growth. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1037–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hocq, L.; Pelloux, J.; Lefebvre, V. Connecting Homogalacturonan-Type Pectin Remodeling to Acid Growth. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voxeur, A.; Höfte, H. Cell Wall Integrity Signaling in Plants: “To Grow or Not to Grow That’s the Question”. Glycobiology 2016, 26, 950–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, F.; Wattier, C.; Rustérucci, C.; Pelloux, J. Homogalacturonan-Modifying Enzymes: Structure, Expression, and Roles in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 5125–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, F.; Mareck, A.; Marcelo, P.; Lerouge, P.; Pelloux, J. Arabidopsis PME17 Activity Can Be Controlled by Pectin Methylesterase Inhibitor4. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e983351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallemí, M.; Montesinos, J.C.; Zarevski, N.; Pribyl, J.; Skládal, P.; Hannezo, E.; Benková, E. Dual Role of Pectin Methyl Esterase Activity in the Regulation of Plant Cell Wall Biophysical Properties. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1612366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obomighie, I.; Prentice, I.J.; Lewin-Jones, P.; Bachtiger, F.; Ramsay, N.; Kishi-Itakura, C.; Goldberg, M.W.; Hawkins, T.J.; Sprittles, J.E.; Knight, H.; et al. Understanding Pectin Cross-Linking in Plant Cell Walls. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.U.; Giarola, V.; Chen, P.; Knox, J.P.; Bartels, D. Craterostigma plantagineum Cell Wall Composition Is Remodelled during Desiccation and the Glycine-Rich Protein CpGRP1 Interacts with Pectins through Clustered Arginines. Plant J. 2019, 100, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyo, P.; Gu, Y.; Hong, M. Impact of Acidic PH on Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharide Structure and Dynamics: Insights into the Mechanism of Acid Growth in Plants from Solid-State NMR. Cellulose 2018, 26, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]