Brassinolide Alleviates Maize Silk Growth Under Water Deficit by Reprogramming Sugar Metabolism and Enhancing Antioxidant Defense

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Location and Design

2.2. Measurement of Silk Length

2.3. Assay of Peroxide Content and Antioxidant Enzyme Activity in Silks

2.4. Determination of MDA Content in Silks

2.5. Determination of Proline Contents in Silks

2.6. Determination of Sugar Contents in Silks

2.7. Determination of Sugar Metabolism Level in Silks

2.8. RNA-Seq Analyses

2.9. RT-qPCR Validation

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Exogenous BR on Silk Length Under Water-Deficit Stress

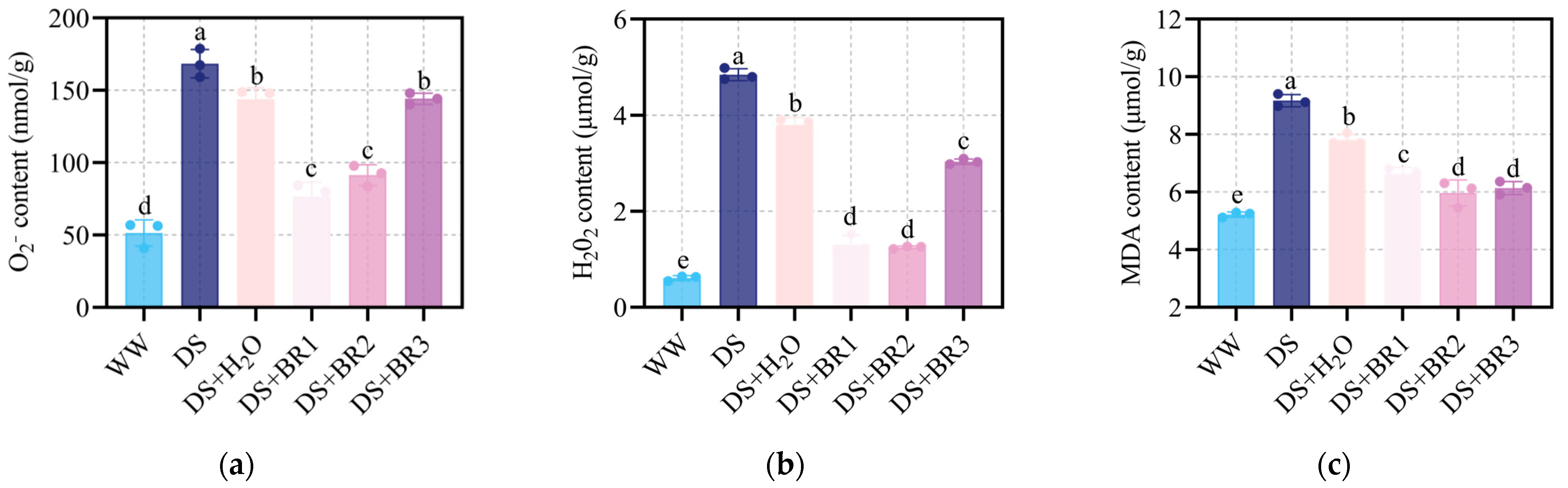

3.2. Effect of Exogenous BR on Oxidative Stress and Membrane Damage in Water-Deficient Silk

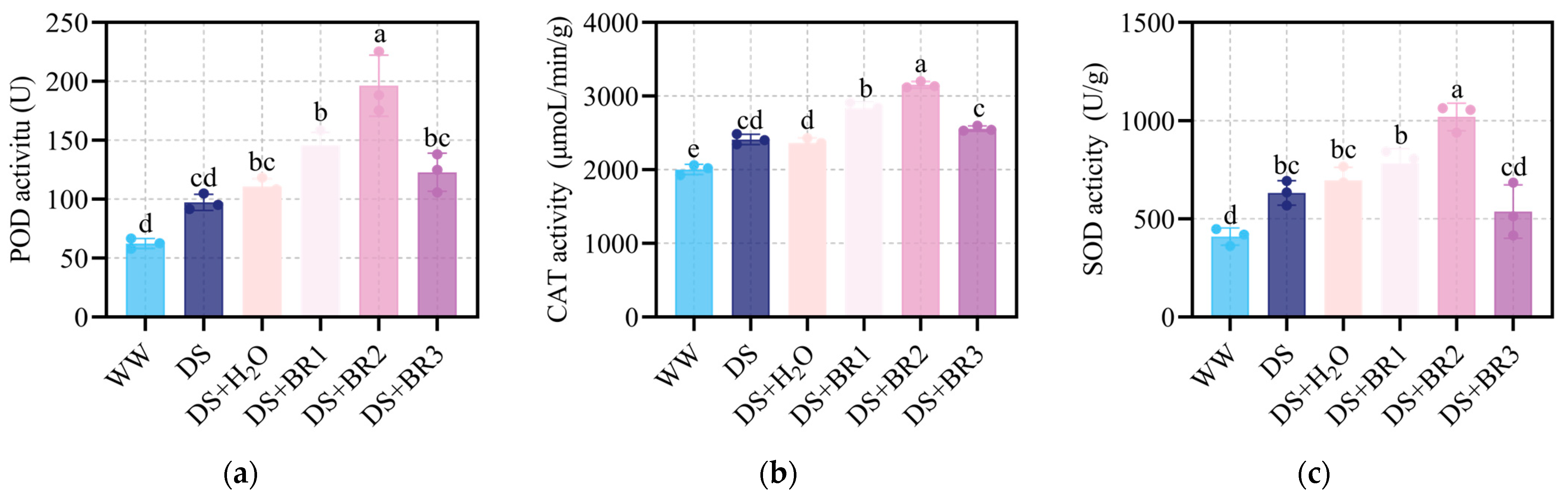

3.3. Effect of Exogenous BR on Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Water-Deficient Silk

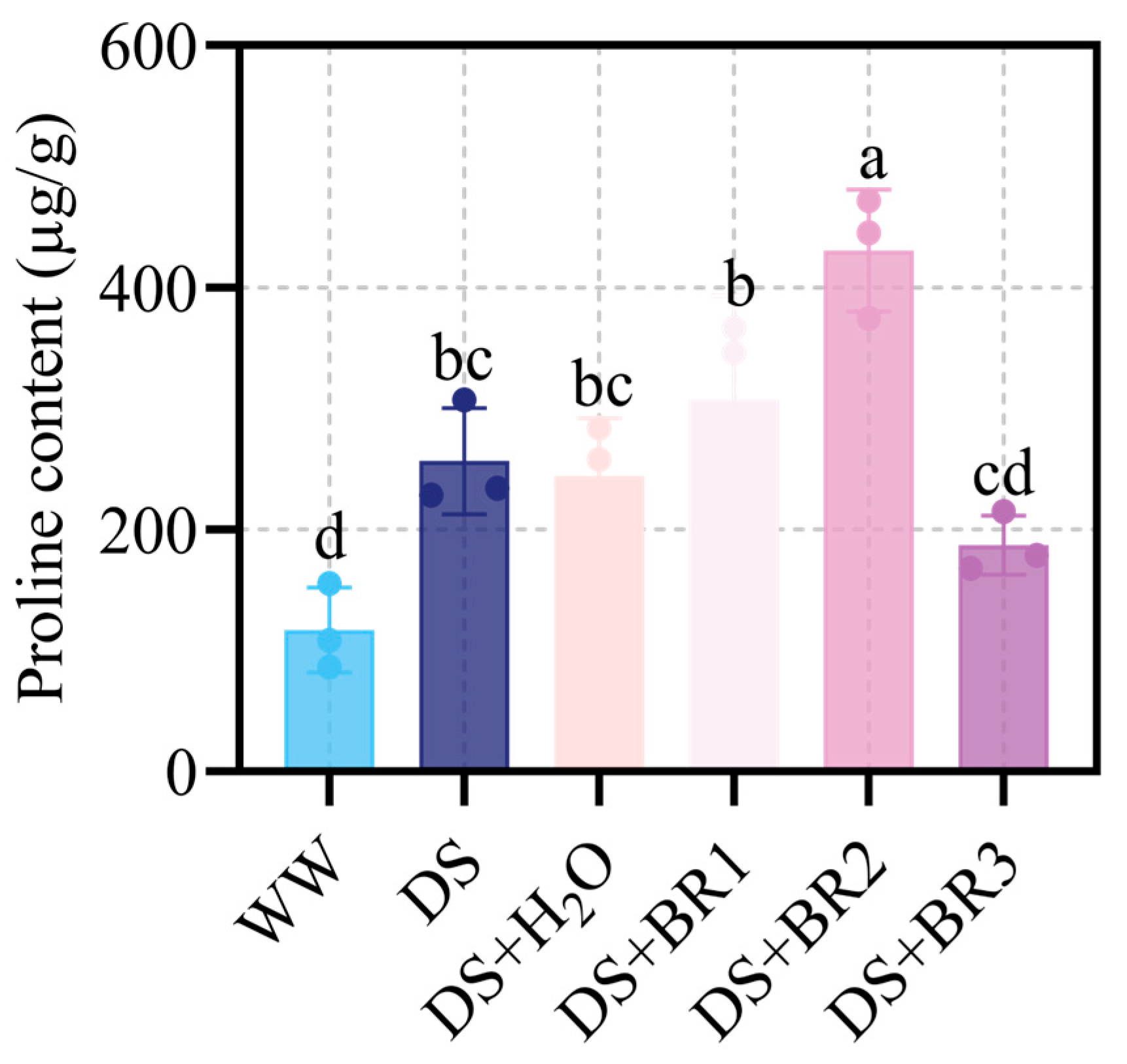

3.4. Effect of Exogenous BR on Proline Content in Water-Deficit-Stressed Silk

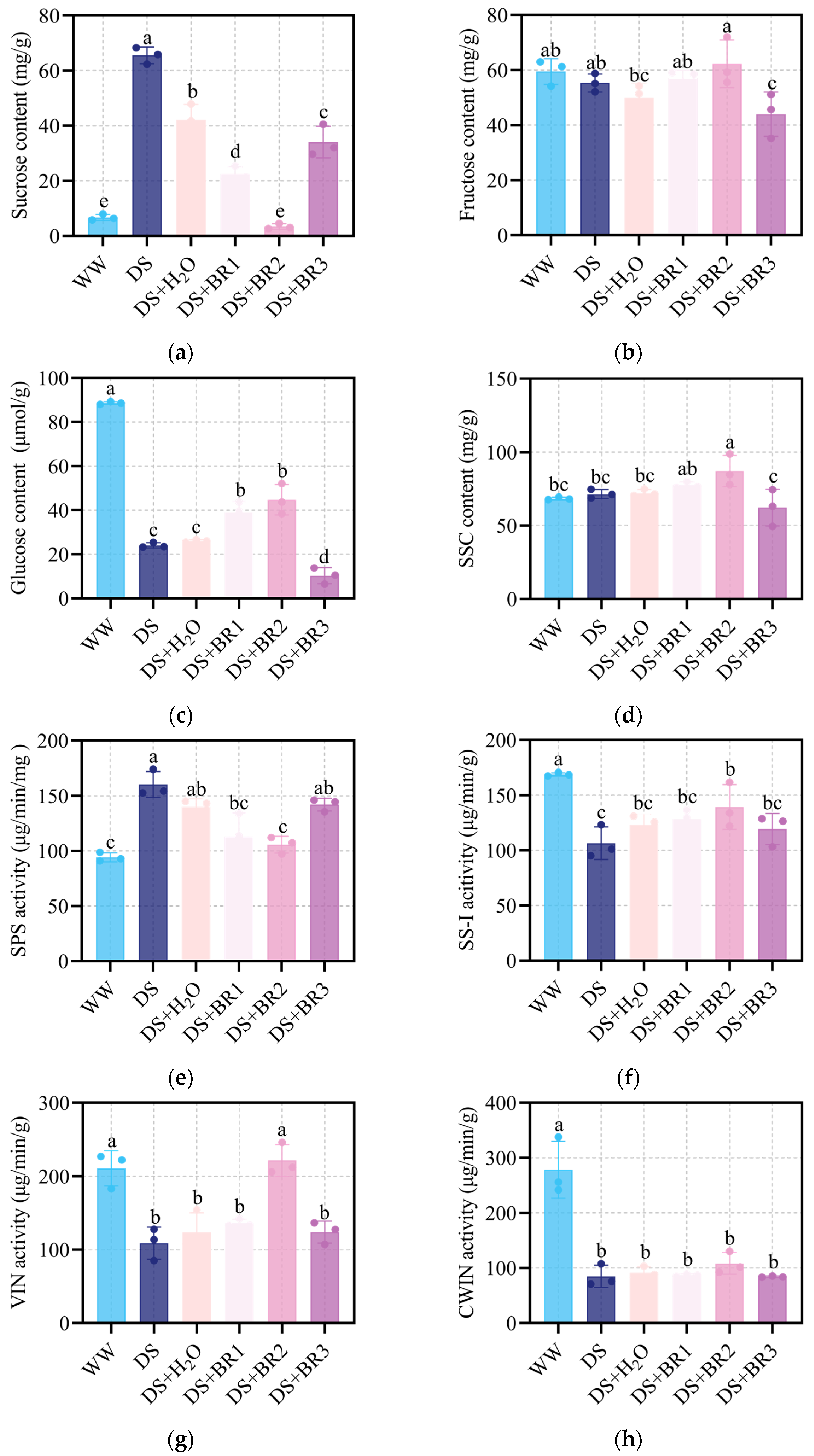

3.5. Effect of Exogenous BR on Sugar Contents and Sugar Metabolism in Water-Deficit-Stressed Silk

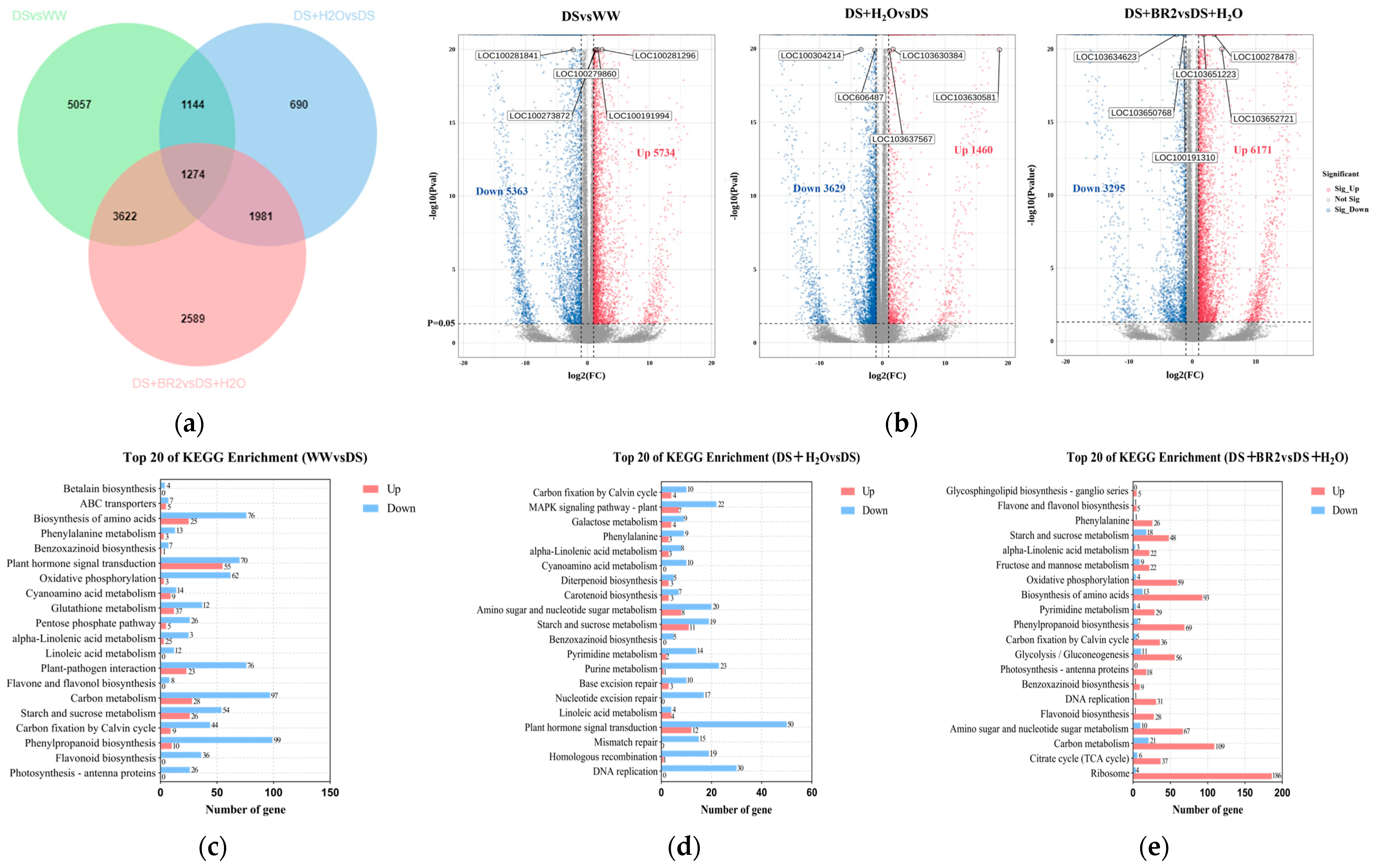

3.6. Transcriptome Analysis of BR-Treated Water-Deficit-Stressed Silk

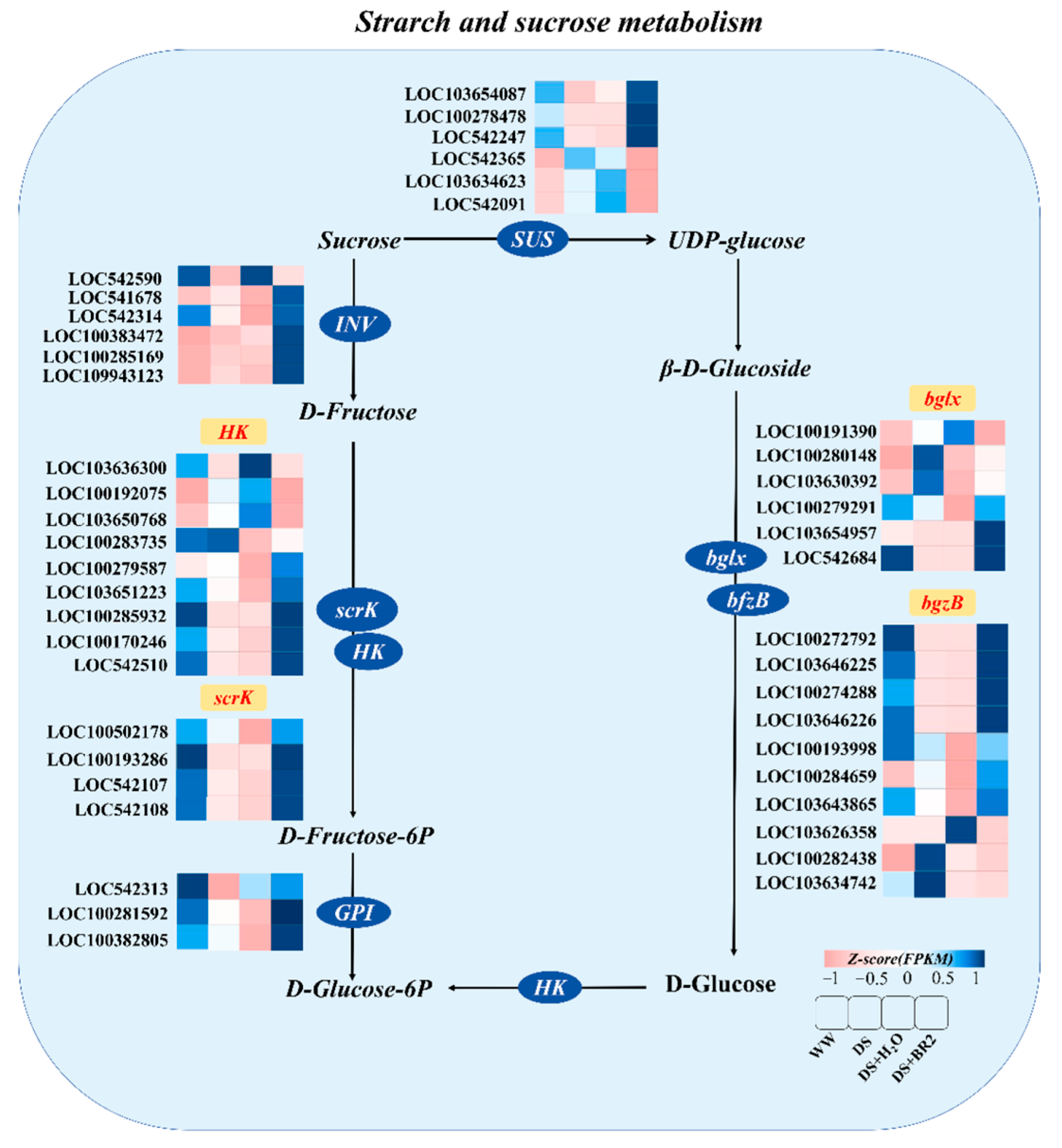

3.7. Expression of Starch and Sucrose Metabolism Genes Under BR Treatment

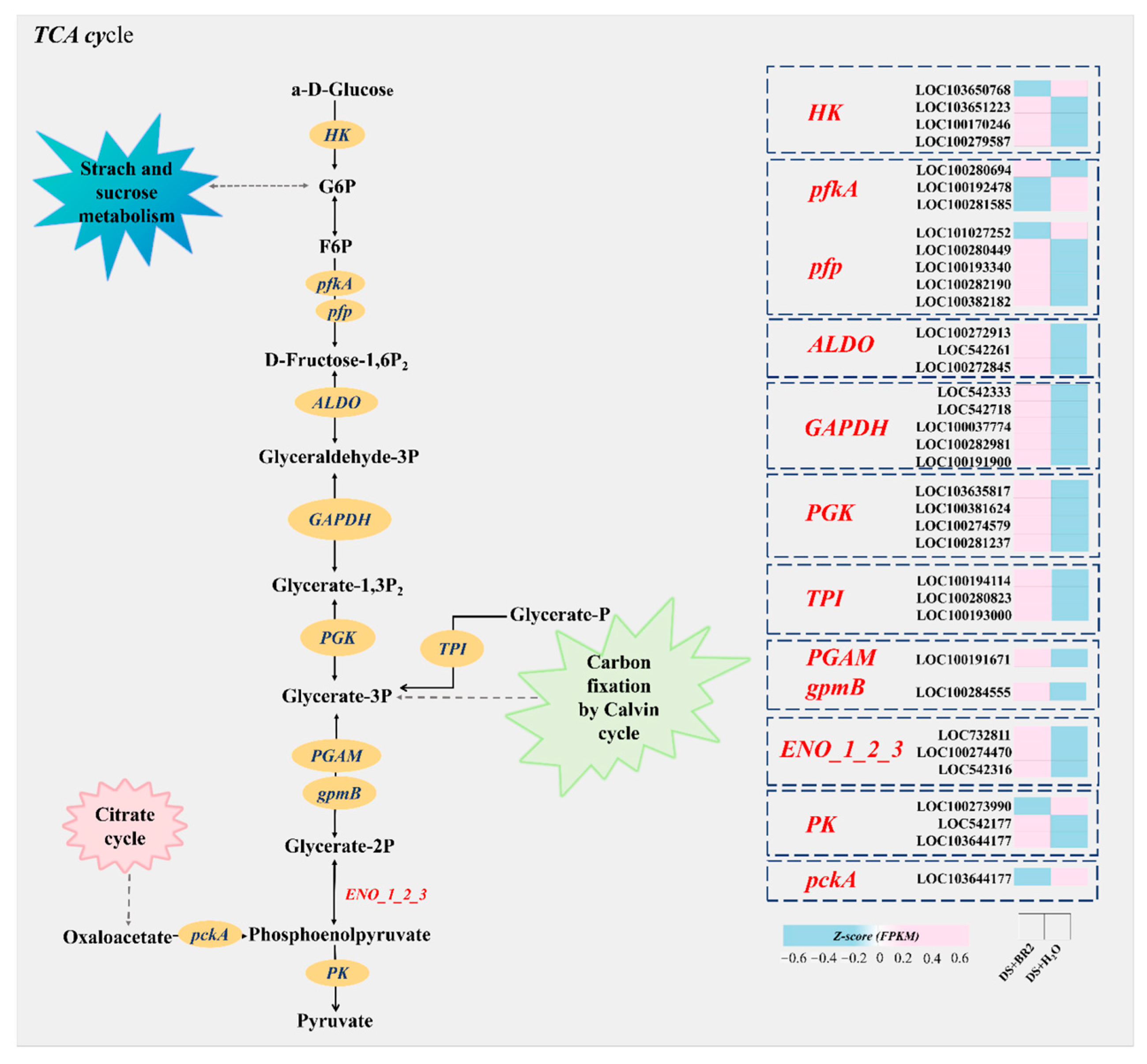

3.8. Expression of Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis Genes Under BR Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Critchely, W.; Siegert, K. A Manual for the Design and Construction of Water Harvesting Schemes for Plant Production; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Dai, A. The Magnitude and Causes of Global Drought Changes in the Twenty-First Century under a Low–Moderate Emissions Scenario. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 4490–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, A.; El-Shazly, H.H.; Tarawneh, R.A.; Börner, A. Screening for drought tolerance in maize (Zea mays L.) germplasm using germination and seedling traits under simulated drought conditions. Plants 2020, 9, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Bano, N.; Kumar, A.; Dubey, A.K.; Asif, M.H.; Sanyal, I.; Pande, V.; Pandey, V. Comparative transcriptomic analysis and antioxidant defense mechanisms in clusterbean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub.) genotypes with contrasting drought tolerance. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2022, 22, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasin, S.; Zavala-García, F.; Niño-Medina, G.; Rodríguez-Salinas, P.A.; Gutiérrez-Diez, A.; Sinagawa-García, S.R.; Lugo-Cruz, E.J.A. Morphological and physiological response of maize (Zea mays L.) to drought stress during reproductive stage. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, D.; Aleksandrov, V.; Anev, S.; Sergiev, I. Comparative study of photosynthesis performance of herbicide-treated Young triticale plants during drought and waterlogging stress. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ahmad, I.; Hussien Ibrahim, M.E.; Qin, B.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, G. Differential Responses of Two Sorghum Genotypes to Drought Stress at Seedling Stage Revealed by Integrated Physiological and Transcriptional Analysis. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Liu, Y.-H.; Ashley, J.; Wu, L.; Song, Y. Coordinated regulation of sucrose and lignin metabolism for arrested silk elongation under drought stress in maize. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 214, 105482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, M.S.; Zhang, C.; Kurjogi, M.M.; Pervaiz, T.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, C.; Lide, C.; Shangguan, L.; Fang, J. Insights into grapevine defense response against drought as revealed by biochemical, physiological and RNA-Seq analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, G.S.F.; Zelong, Z.; Adnan, R.; Ul, H.I.; Asim, A.; Shakil, A.; Yinxia, W.; Tajammal, K.M.; Rehana, S.; Yunling, P. Brassinosteroids induced drought resistance of contrasting drought-responsive genotypes of maize at physiological and transcriptomic levels. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 961680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Jones, A.; Rose, R.J.; Ruan, Y.; Song, Y. Mitigating drought-associated reproductive failure in maize: From physiological mechanisms to practical solutions. Crop J. 2025, 13, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Dai, M. Improving crop drought resistance with plant growth regulators and rhizobacteria: Mechanisms, applications, and perspectives. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.; Arshad, M.; Aslam, S. Comprehensive Review on the Role of Exogenous Phytohormones in Enhancing Temperature Stress Tolerance in Plants. J. Crop Health 2025, 77, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumanova, N.; Akimbayeva, N.; Myrzakhmetova, N.; Dzhiembaev, B.; Ku, A.; Diyarova, B.; Seilkhanov, O.; Kishibayev, K.; Meldeshov, A.; Saparbekova, I. A comprehensive review of new generation plant growth regulators. ES Food Agrofor. 2024, 17, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.A.; McAdam, S.A. Misleading conclusions from exogenous ABA application: A cautionary tale about the evolution of stomatal responses to changes in leaf water status. Plant Signal. Behav. 2019, 14, 1610307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Liu, H.Q.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Hasan, M.M. Aba-induced active stomatal closure in bulb scales of Lanzhou lily. Plant Signal. Behav. 2025, 20, 2446865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chollet, J.F.; Marivingt-Mounir, C.; La Camera, S.; Oussou, R. Salicylic acid: A key natural foundation for next-generation plant defense stimulators. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, M.; Zhang, D.; Liao, K.; Chen, X.; Ahmed, N.; Wang, D.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z. The past, present, and future of plant activators targeting the salicylic acid signaling pathway. Genes 2024, 15, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Han, Z.; Chepkorir, D.; Fang, W.; Ma, Y. Effect of Exogenous Jasmonates on Plant Adaptation to Cold Stress: A Comprehensive Study Based on a Systematic Review with a Focus on Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, Y.S.; Kretynin, S.V.; Filepova, R.; Dobrev, P.I.; Martinec, J.; Kravets, V.S. Polyamines metabolism and their biological role in plant cells: What do we really know? Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 23, 997–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Qu, J.; Fang, Y.; Yang, H.; Lai, W.; Pan, L.; Liu, J.H. Polyamines: The valuable bio-stimulants and endogenous signaling molecules for plant development and stress response. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.J.; Shi, X.Z.; Qu, Y.N.; Li, S.Y.; Ai, G.; Wang, Y.Z.; Zeng, L.Q.; Liu, X.L.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.H. Insights into the synergistic effects of exogenous glycine betaine on the multiphase metabolism of oxyfluorfen in Oryza sativa for reducing environmental risks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 491, 137970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, G.; Anna, J.; Michal, D.; Ewa, P.; Jana, O.; Iwona, S. Barley Brassinosteroid Mutants Provide an Insight into Phytohormonal Homeostasis in Plant Reaction to Drought Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Lu, D. Effects of exogenous brassinolide application at the silking stage on nutrient accumulation, translocation and remobilization of waxy maize under post-silking heat stress. Agriculture 2022, 12, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S.; Wang, L.; Farooq, M.; Hussain, M.; Xue, L.; Zou, C. Brassinolide application improves the drought tolerance in maize through modulation of enzymatic antioxidants and leaf gas exchange. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2011, 197, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Lee, D.J.; Cheema, S.; Aziz, T. Drought stress: Comparative time course action of the foliar applied glycinebetaine, salicylic acid, nitrous oxide, brassinosteroids and spermine in improving drought resistance of rice. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2010, 196, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sheng, J.; Xu, Y.; Xiong, F.; Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Role of brassinosteroids in rice spikelet differentiation and degeneration under soil-drying during panicle development. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Liu, M.; Yang, H.; Dai, L.; Wang, L. Brassinosteroids Regulate the Water Deficit and Latex Yield of Rubber Trees. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalbaev, A.; Fedyaev, V.; Lubyanova, A.; Yuldashev, R.; Allagulova, C. 24-Epibrassinolide Reduces Drought-Induced Oxidative Stress by Modulating the Antioxidant System and Respiration in Wheat Seedlings. Plants 2024, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, W.; Li, Y.; Collins, B.; Song, Y.h. Response characteristics of leaf assimilate supply and silk sucrose metabolism in maize to drought stress. In Proceedings of the 20th Agronomy Australia Conference, Toowoomba, Australia, 18–22 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Lei, W. Evidence of arrested silk growth in maize at high planting density using phenotypic and transcriptional analyses. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 3148–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.-L. Signaling Role of Sucrose Metabolism in Development. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 763–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bishop, E.; Bridges, W.C.; Tharayil, N.; Sekhon, R.S. Sugar partitioning and source–sink interaction are key determinants of leaf senescence in maize. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 2597–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, C.; Juárez-Colunga, S.; Trachsel, S.; Marsch-Martínez, N.; Gillmor, C.S.; Tiessen, A. Analysis of Global Gene Expression in Maize (Zea mays) Vegetative and Reproductive Tissues That Differ in Accumulation of Starch and Sucrose. Plants 2022, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Ma, H.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Li, P.; Xia, T. Overexpression of ZmSUS1 increased drought resistance of maize (Zea mays L.) by regulating sucrose metabolism and soluble sugar content. Planta 2024, 259, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.M.; DeLong, J.M.; Forney, C.F.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 59, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Cai, X.; Liu, Y.H.; Jones, A.; Song, Y. Regulation of Maize (Zea mays L.) Silk Extension Tolerance to Moderate Drought Stress Associated With Sucrose Metabolism, Phytohormone and Secondary Metabolism. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 2026, 212, e70140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufford, M.; Seetharam, A.S.; Woodhouse, M.; Chougule, K.; Ou, S.; Liu, J.; Ricci, W.A.; Guo, T.; Olson, A.J.; Qiu, Y. De novo assembly, annotation, and comparative analysis of 26 diverse maize genomes. Science 2021, 373, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.; Anders, S.; Huber, W. Differential analysis of count data—The DESeq2 package. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 10–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Niu, Y.; Zakir, H.; Zhao, B.; Bai, X.; Taotao, M. New insights into light spectral quality inhibits the plasticity elongation of maize mesocotyl and coleoptile during seed germination. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1152399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilevskaya, O.N.; Yu, G.; Meng, X.; Xu, J.; Stephenson, E.; Estrada, S.; Chilakamarri, S.; Zastrow-Hayes, G.; Thatcher, S. Developmental and transcriptional responses of maize to drought stress under field conditions. Plant Direct 2019, 3, e00129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, C.; Zhang, D.; He, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z. Effects of maize organ-specific drought stress response on yields from transcriptome analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Lee, B.-M. Effects of climate change and drought tolerance on maize growth. Plants 2023, 12, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukašinović, N.; Wang, Y.; Vanhoutte, I.; Fendrych, M.; Guo, B.; Kvasnica, M.; Jiroutová, P.; Oklestkova, J.; Strnad, M.; Russinova, E. Local brassinosteroid biosynthesis enables optimal root growth. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Ge, X.; Li, F. BR deficiency causes increased sensitivity to drought and yield penalty in cotton. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujita, D.; Basra, S.M. Plant drought stress: Effects, mechanisms and management. Agron. Sustain. Agric. 2009, 29, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.S.; Hussain, A.; Hussain, S.J.; Wani, O.A.; Zahid Nabi, S.; Dar, N.A.; Baloch, F.S.; Mansoor, S. Plant drought stress tolerance: Understanding its physiological, biochemical and molecular mechanisms. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2021, 35, 1912–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Miao, Y.; Kong, J.; Lindsey, K.; Zhang, X.; Min, L. ROS signaling and its involvement in abiotic stress with emphasis on heat stress-driven anther sterility in plants. Crop Environ. 2024, 3, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Zulfiqar, T.; Yang, H.; Farooq, M. Strigolactones mitigate drought stress in maize by improving chloroplast protection stomatal function and antioxidant defense mechanisms. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2025, 70, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, S.C.; Logan, B.A. Energy dissipation and radical scavenging by the plant phenylpropanoid pathway. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 355, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, L.; Lv, J. The spike plays important roles in the drought tolerance as compared to the flag leaf through the phenylpropanoid pathway in wheat. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 152, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghifar, H.; Ragauskas, A.J. Lignin as a Natural Antioxidant: Chemistry and Applications. Macromol 2025, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yao, X.; Liu, X.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, X. Brassinolide can improve drought tolerance of maize seedlings under drought stress: By inducing the photosynthetic performance, antioxidant capacity and ZmMYB gene expression of maize seedlings. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 2092–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.; Sattar, A.; Sher, A.; Ijaz, M.; Baig, A.; Naz, I.; Almaghasla, M.; Hamed, L.; Ramadan, K.; El-Mogy, M. Exogenous application of silicon and brassinosteroids alleviate the adversities of drought stress on maize through up-regulation of photosynthetic efficiency, antioxidants defense system and osmotic adjustment. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 72, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinselmeier, C.; Westgate, M.E.; Schussler, J.R.; Jones, R.J. Low water potential disrupts carbohydrate metabolism in maize (Zea mays L.) ovaries. Plant Physiol. 1995, 107, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Ma, S.; Chen, X.M.; Yi, F.; Li, B.B.; Liang, X.G.; Liao, S.J.; Gao, L.H.; Zhou, S.L.; Ruan, Y.L. A transcriptional landscape underlying sugar import for grain set in maize. Plant J. 2022, 110, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibarat, Z.; Saidi, A.; Zabet-Moghaddam, M.; Shahbazi, M.; Zeinalabedini, M.; Gorji, A.M.; Mirzaei, M.; Haynes, P.A.; Hosseini Salekdeh, G.; Ghaffari, M.R. Integrated proteome and metabolome analysis of the penultimate internodes revealing remobilization efficiency in contrasting barley genotypes under water stress. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, S.-F.; Huang, Y.-F.; Chen, D.-L.; Zhong, C. Dihydroporphyrin iron (III) enhances low temperature tolerance by increasing carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Andrographis paniculata. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1522481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdar, B.; Ahmed, N.; Tu, P.; Li, Z.H. Beyond Energy: How small-molecule sugars fuel seed life and shape next-generation crop technologies. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2025, 211, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guehaz, K.; Chakou, F.Z.; Ciani, M.; Boual, Z.; Adessi, A.; Telli, A.; Mohamed, H.I. The Effect of Saccharides on Plant response to stress and their regulatory function during development. In Elicitors for Sustainable Crop Production: Overcoming Abiotic Stress Challenges in Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 333–359. [Google Scholar]

- Sprent, N.; Cheung, C.M.; Shameer, S.; Ratcliffe, R.G.; Sweetlove, L.J.; Töpfer, N. Metabolic modeling reveals distinct roles of sugars and carboxylic acids in stomatal opening as well as unexpected carbon fluxes. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koae252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Ruan, M.; Ye, Q.; Wang, R.; Yao, Z.; Zhou, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Wan, H. Roles and regulations of acid invertases in plants: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Plants 2025, 14, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhal, S.; Pal, H. Regulation of glycolysis and krebs cycle during biotic and abiotic stresses. In Photosynthesis and Respiratory Cycles During Environmental Stress Response in Plants; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 263–308. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, M.; Song, Y.C.; Zargar, M.; Chen, M.X.; Lin, S.Y.; Zhu, F.Y.; Song, T. Unlocking bamboo’s fast growth: Exploring the vital role of non-structural carbohydrates (NSCs). Plant J. 2025, 122, e70147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo-Gonzalez, R.; Rodriguez-Buenfil, I.M.; Reynoso, O.G. Anti-inflammatory molecules. In Recent Advances in Phytochemical Research; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025; Volume 93. [Google Scholar]

- Dorion, S.; Ouellet, J.C.; Rivoal, J. Glutathione metabolism in plants under stress: Beyond reactive oxygen species detoxification. Metabolites 2021, 11, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y.-L.; Chourey, P.S. Carbon partitioning in developing seed. In Handbook of Seed Science and Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana, A. Nucleotide sugars and the transporters that put them at the right place. In Plant Cell Walls; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Soltani Gishini, M.F.; Kurokawa, T.; Singh, R.M.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Role of cuticle, sterols, sphingolipids, and glycerolipids in plant defense. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, eraf255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Cheng, Z.; Dai, L.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Anicet, G.; Yu, Y.; Song, Y. Brassinolide Alleviates Maize Silk Growth Under Water Deficit by Reprogramming Sugar Metabolism and Enhancing Antioxidant Defense. Plants 2026, 15, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010139

Xu J, Cheng Z, Dai L, Li W, Chen L, Anicet G, Yu Y, Song Y. Brassinolide Alleviates Maize Silk Growth Under Water Deficit by Reprogramming Sugar Metabolism and Enhancing Antioxidant Defense. Plants. 2026; 15(1):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010139

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jinrong, Zhicheng Cheng, Li Dai, Wangjing Li, Liyuan Chen, Gatera Anicet, Yi Yu, and Youhong Song. 2026. "Brassinolide Alleviates Maize Silk Growth Under Water Deficit by Reprogramming Sugar Metabolism and Enhancing Antioxidant Defense" Plants 15, no. 1: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010139

APA StyleXu, J., Cheng, Z., Dai, L., Li, W., Chen, L., Anicet, G., Yu, Y., & Song, Y. (2026). Brassinolide Alleviates Maize Silk Growth Under Water Deficit by Reprogramming Sugar Metabolism and Enhancing Antioxidant Defense. Plants, 15(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010139