Assessment of Bacterial Diversity and Rhizospheric Community Shifts in Maize (Zea mays L.) Grown in Soils with Contrasting Productivity Levels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Key Differences in Physicochemical Properties

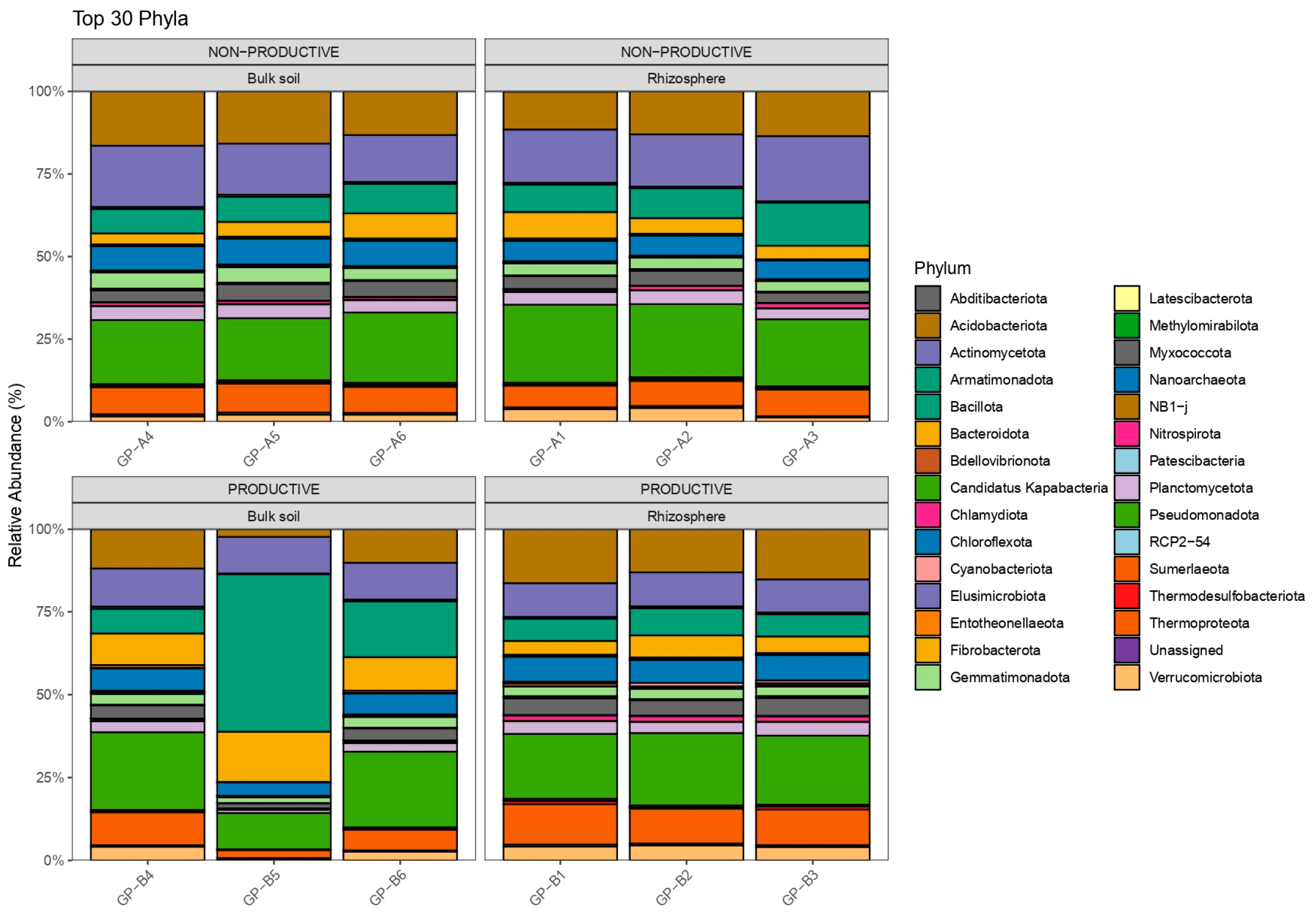

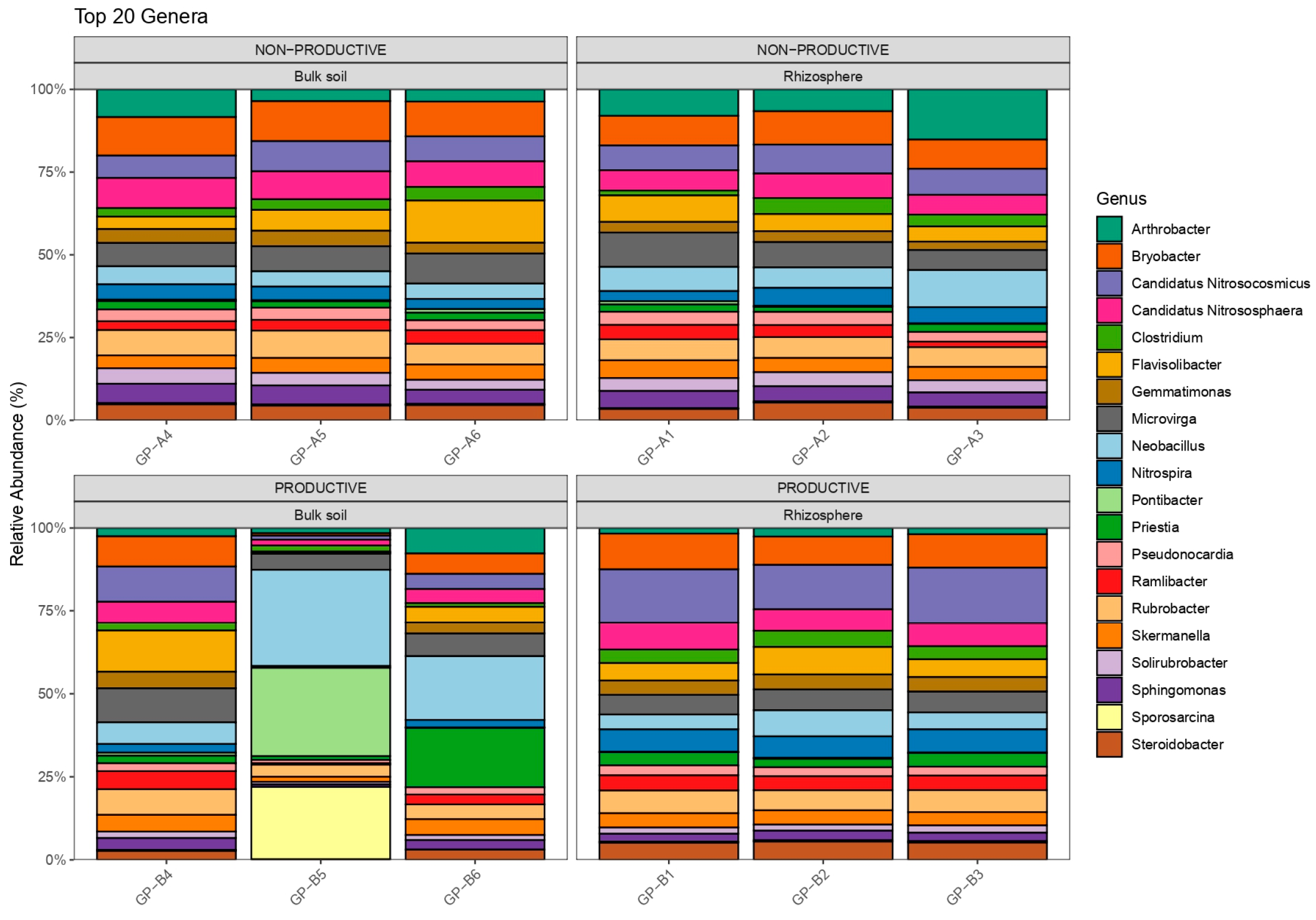

2.2. Evaluation of Bacterial Diversity Using 16S rRNA Sequencing

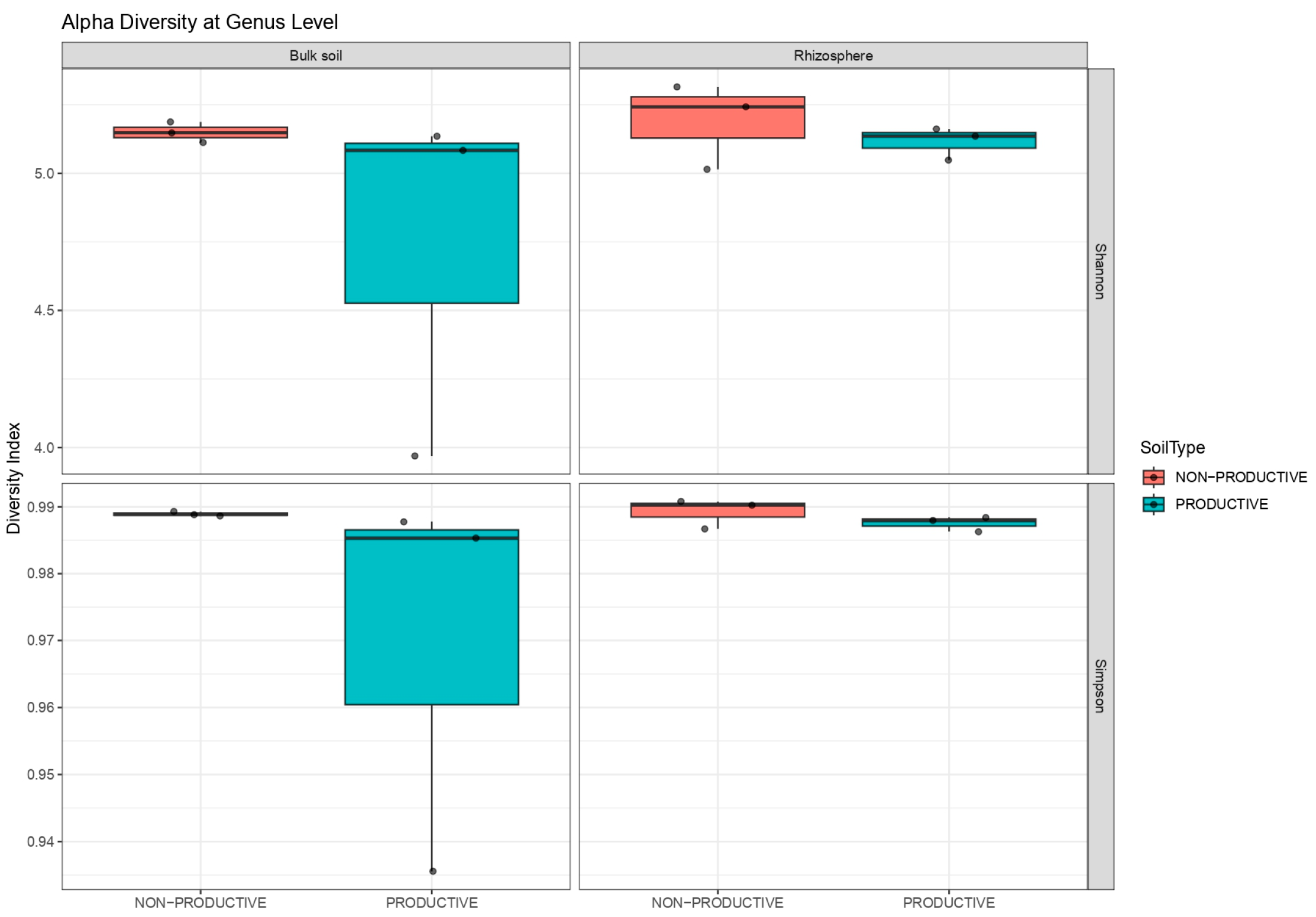

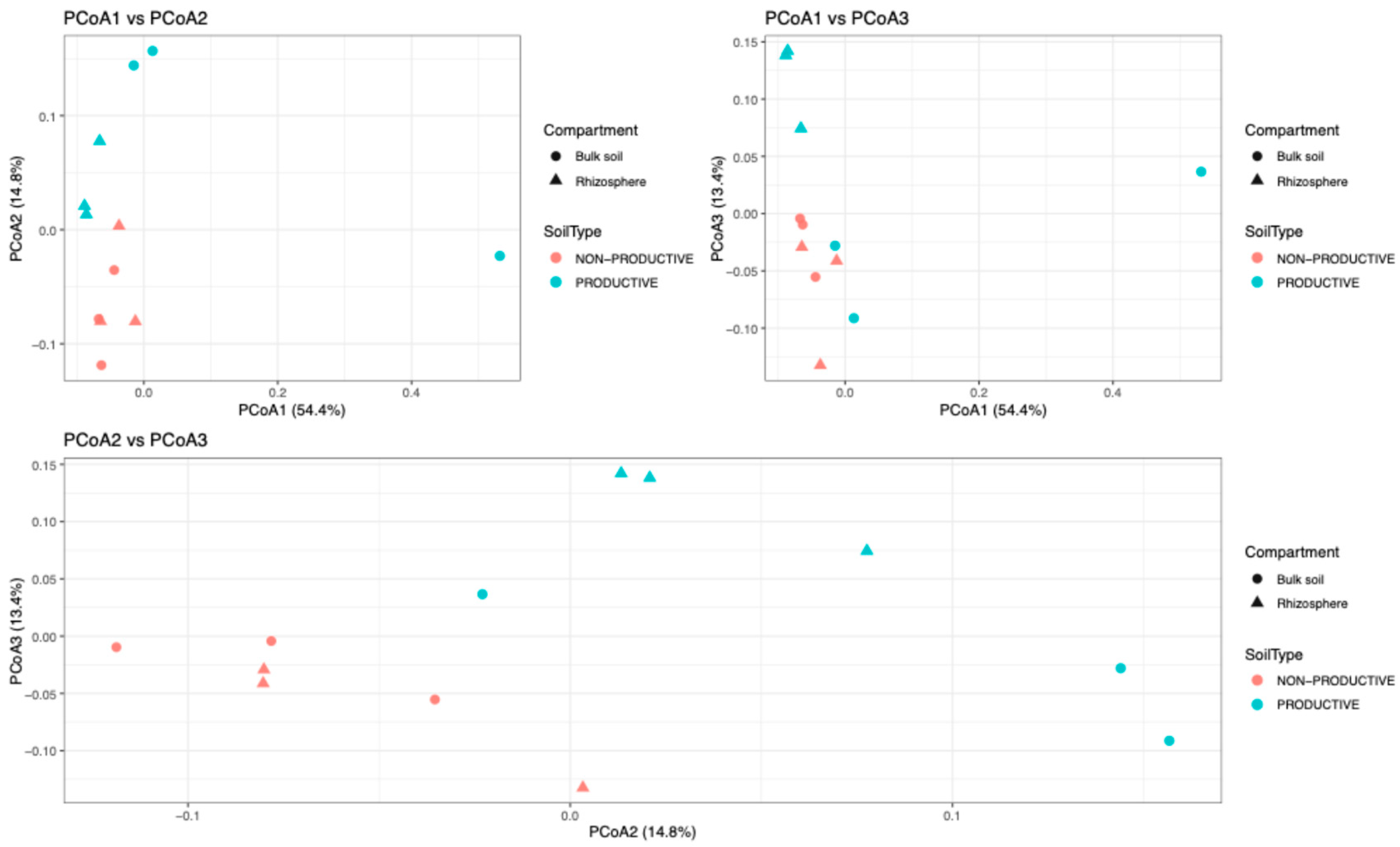

2.3. Alpha and Beta Diversity Analysis

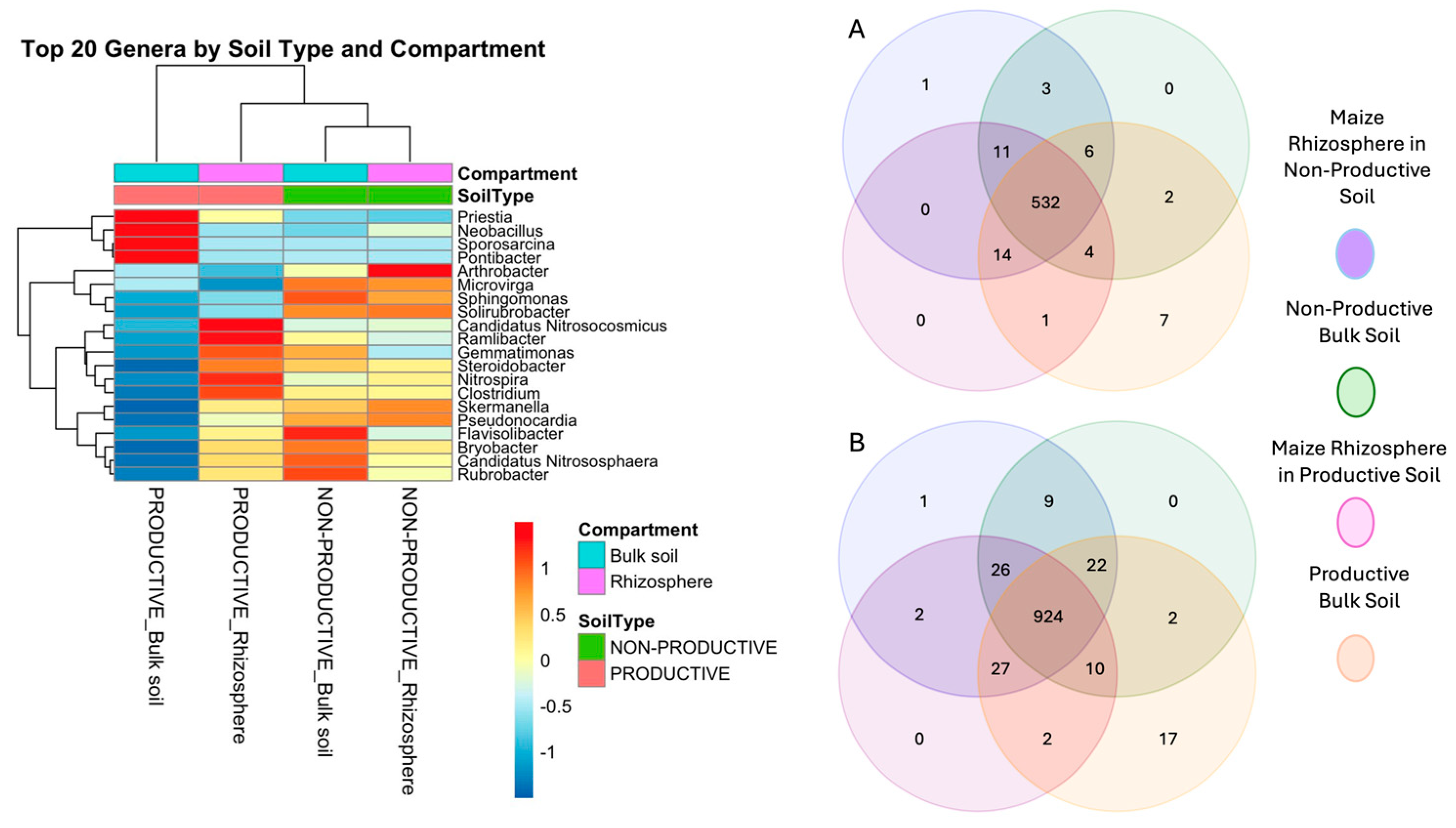

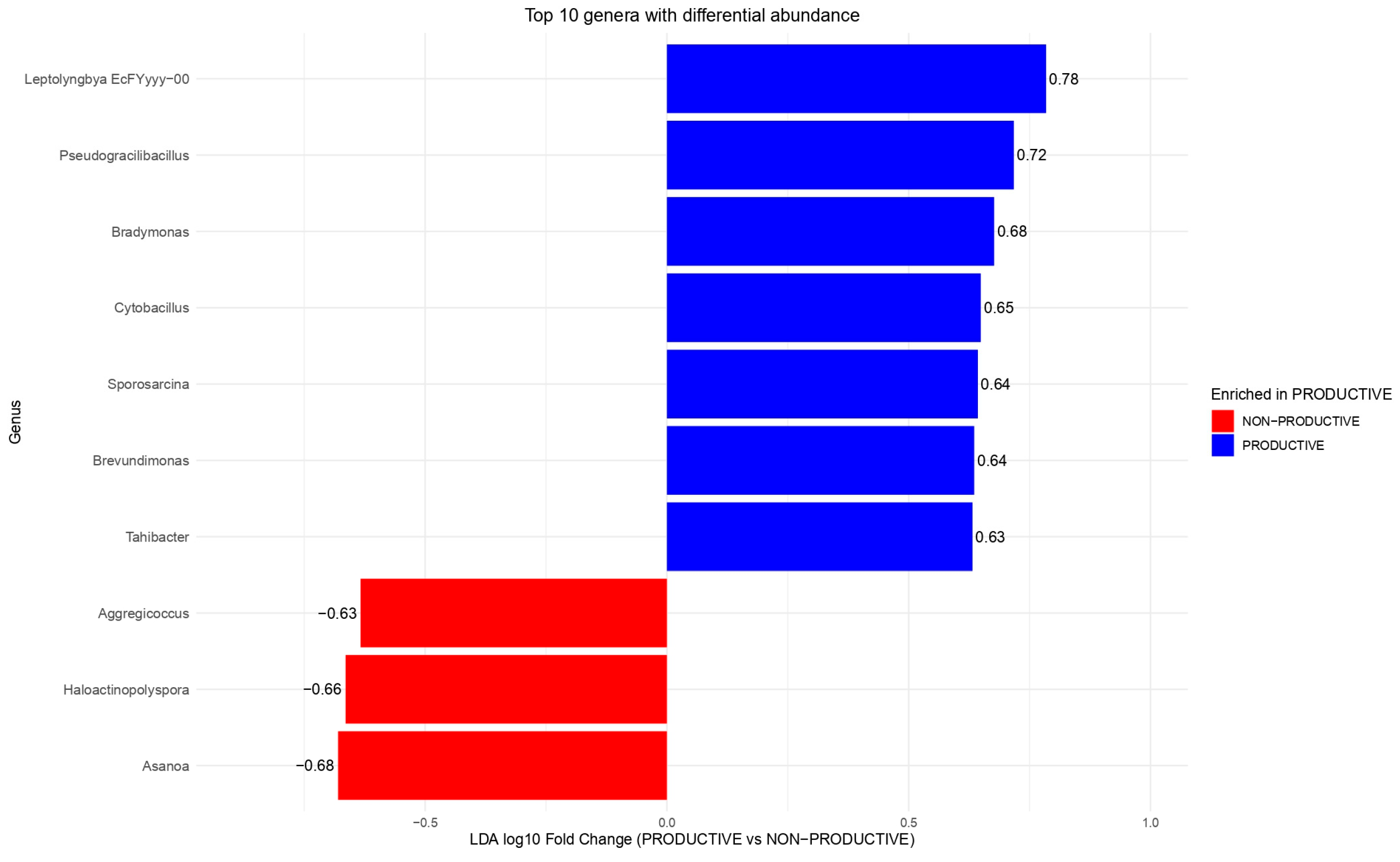

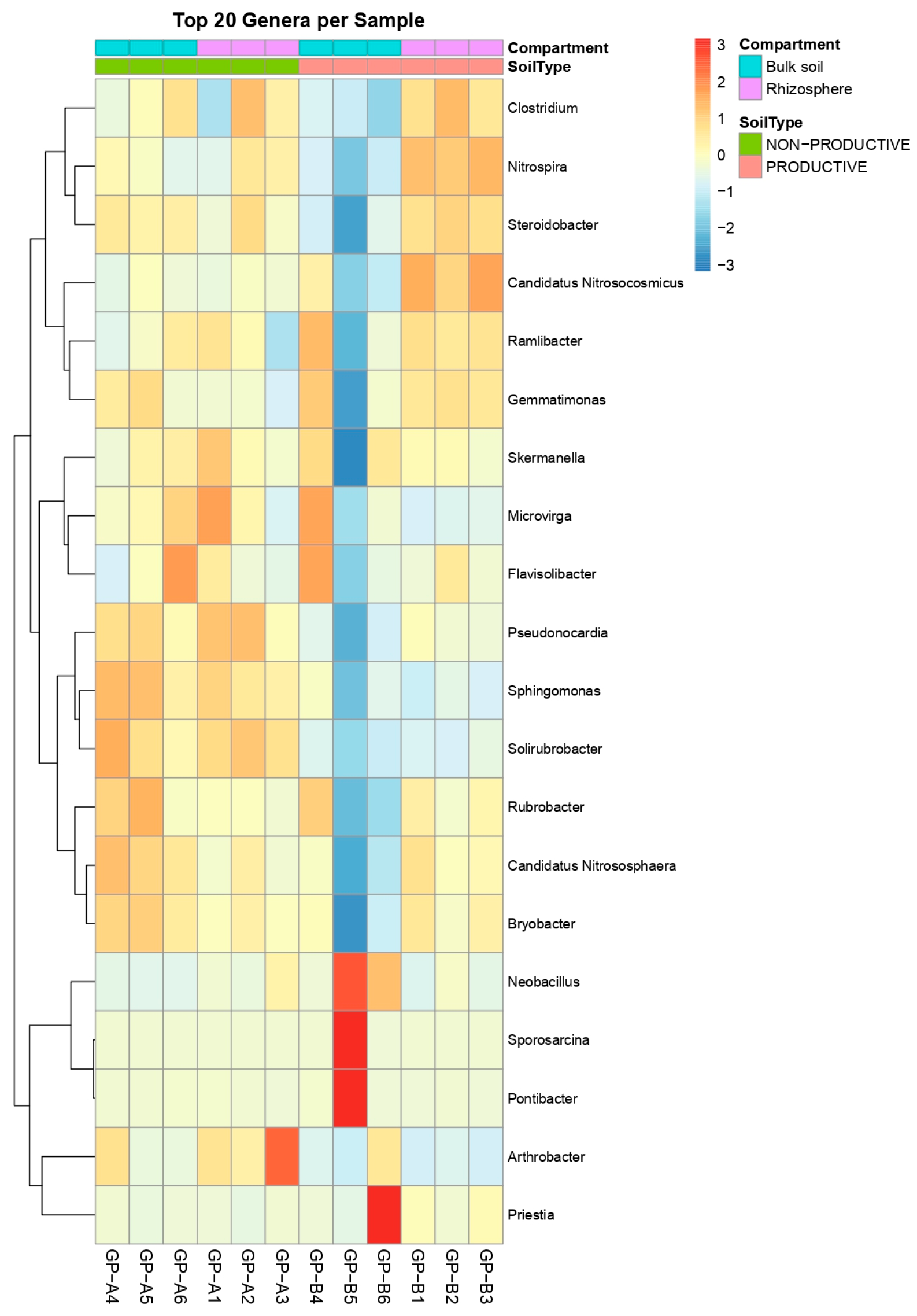

2.4. Differential Abundance and Key Shared Taxa

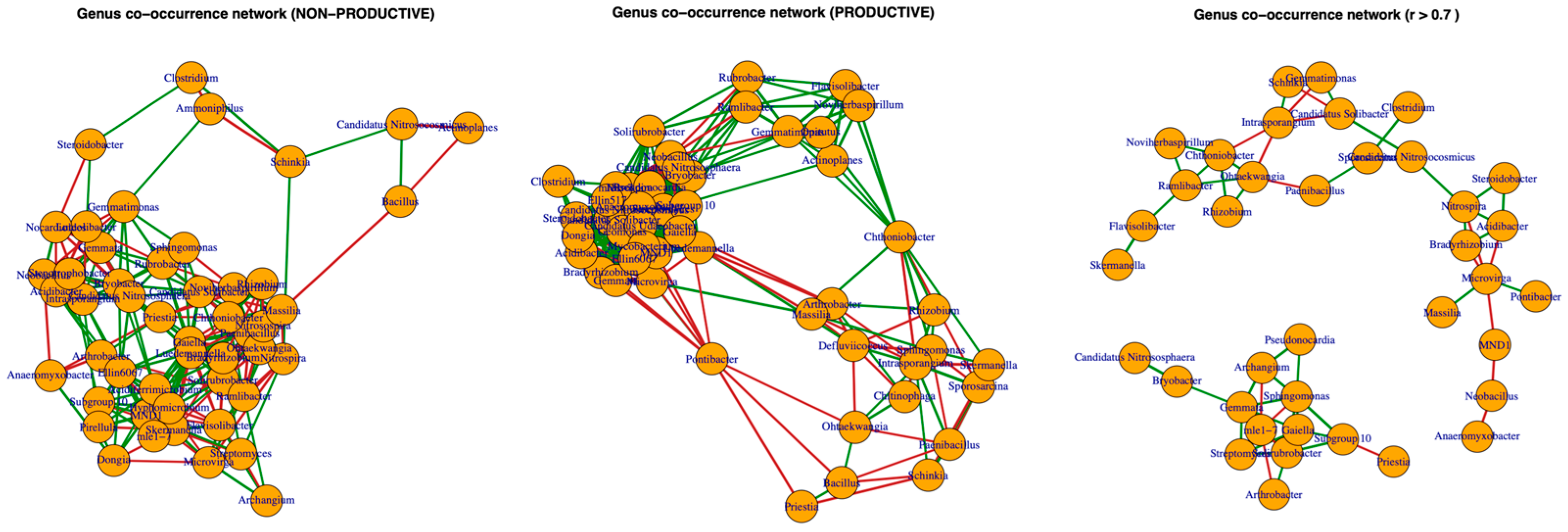

2.5. Co-Occurrence Networks

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

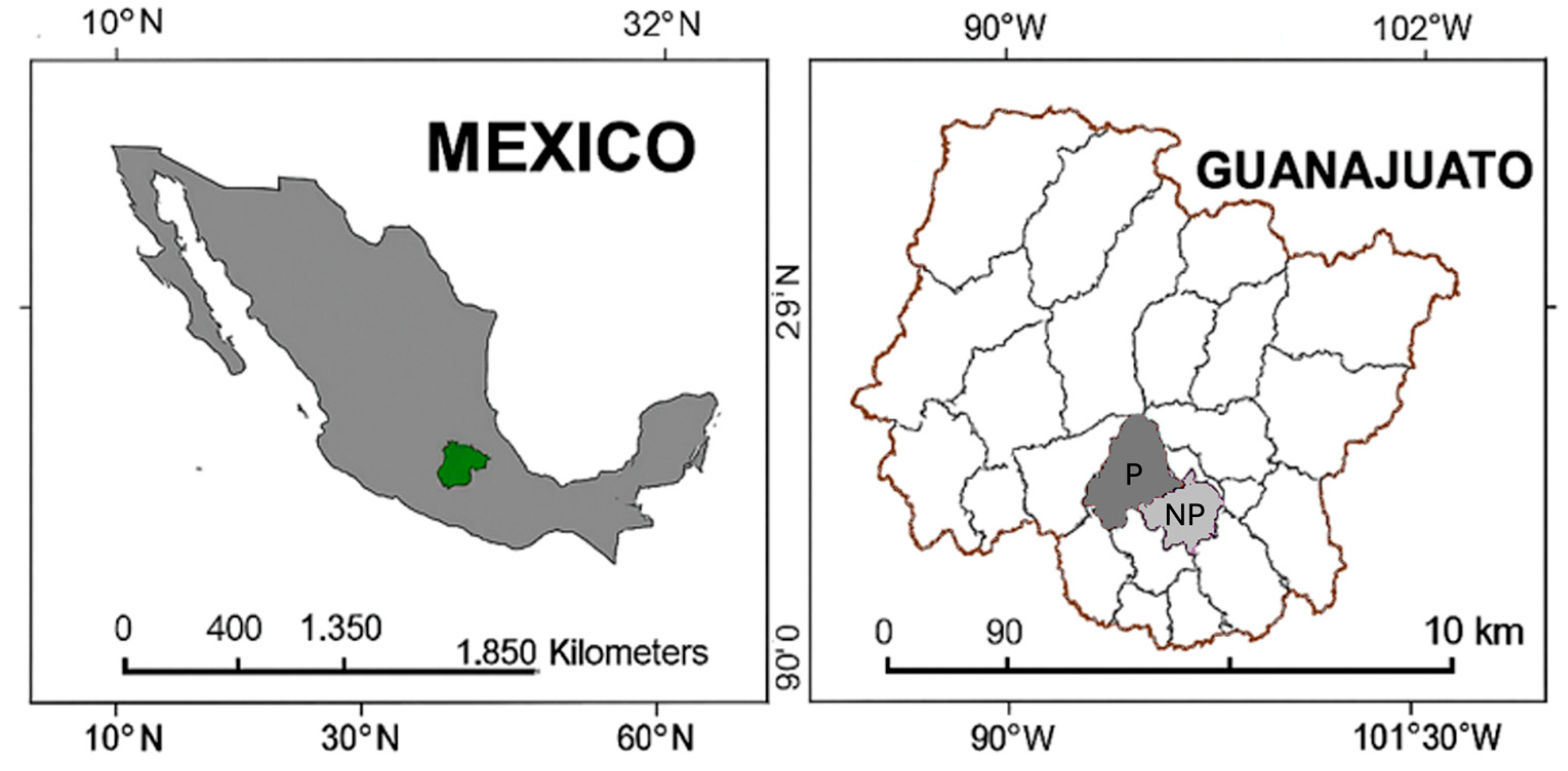

4.1. Study Site and Sampling

4.2. DNA Extraction and Microbial Soil Sequencing

4.3. Sequence Processing and Quality Assurance

4.4. Inference of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs)

4.5. Taxonomic Classification

4.6. Community Structure and Visualization

4.7. Differential Abundance Analysis

4.8. Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giller, K.E.; Delaune, T.; Silva, J.V.; Descheemaeker, K.; Van de Ven, G.; Schut, A.G.; van Ittersum, M.K. The future of farming: Who will produce our food? Food Secur. 2021, 13, 1073–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlaug, N.E. The Green Revolution Revisited and the Road Ahead; Nobelprize.org: Stockholm, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yanai, J.; Tanaka, S.; Nakao, A.; Abe, S.S.; Hirose, M.; Sakamoto, K.; Kyuma, K. Long-term changes in paddy soil fertility. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sheershwal, A.; Bisht, S. Rhizobacteria revolution: Amplifying crop resilience and yield. J. Basic Microbiol. 2025, 65, e039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, A.J.; Amalraj, E.L.D.; Talluri, V.R. Commercial aspects of biofertilizers and biostimulants development. In Rhizosphere Microbes: Soil and Plant Functions; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 655–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoso, M.A.; Wagan, S.; Alam, I.; Hussain, A.; Ali, Q.; Saha, S.; Liu, F. Impact of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on plant nutrition and root characteristics: Current perspective. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, D.; Pande, V.; Pandey, S.C.; Samant, M. Recent advances in PGPR and molecular mechanisms involved in drought stress resistance. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Pandey, V.K.; Jain, D.; Singh, G.; Brar, N.S.; Taufeeq, A.; Rustagi, S. PGPR-induced plant signalling and stress management. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Takishita, Y.; Zhou, G.; Smith, D.L. Plant associated rhizobacteria for biocontrol and plant growth enhancement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 634796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pei, Y.; Wang, X.; Dai, X.; Zhu, M. Antimicrobial metabolites from PGPR. Adv. Agrochem. 2021, 3, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, N.L.G. La agricultura del maíz y el sorgo en el Bajío mexicano: Revolución verde, sequías y expansión forrajera, 1940–2021. Hist. Agrar. 2023, 91, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Guzmán, A.; Bedolla-Rivera, H.I.; Conde-Barajas, E.; Negrete-Rodríguez, M.d.l.L.X.; Lastiri-Hernández, M.A.; Gámez-Vázquez, F.P.; Álvarez-Bernal, D. Corn Cropping Systems in Agricultural Soils from the Bajio Region of Guanajuato: Soil Quality Indexes (SQIs). Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteros-Urquieta, C.; Francois, J.P.; Aguilar-Muñoz, P.; Molina, V. Soil Microbial Communities Changes Along Depth and Contrasting Facing Slopes at the Parque Nacional La Campana, Chile. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hu, H.W.; Yang, G.W.; Cui, Z.L.; Chen, Y.L. Crop rotational diversity enhances soil microbiome network complexity and multifunctionality. Geoderma 2023, 436, 116562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, Q.; Reitz, T.; Schädler, M.; Hodgskiss, L.H.; Peng, J.; Schnabel, B.; Heintz-Buschart, A. Metabolic potential of Nitrososphaera-associated clades. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelkner, J.; Huang, L.; Lin, T.W.; Schulz, A.; Osterholz, B.; Henke, C.; Schlüter, A. Abundance, classification and genetic potential of Thaumarchaeota in metagenomes of European agricultural soils: A meta-analysis. Environ. Microbiome 2023, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelkner, J.; Henke, C.; Lin, T.W.; Pätzold, W.; Hassa, J.; Jaenicke, S.; Schlüter, A. Effect of long-term farming practices on agricultural soil microbiome members represented by metagenomically assembled genomes (MAGs) and their predicted plant-beneficial genes. Genes 2019, 10, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltruschat, H.; Santos, V.M.; da Silva, D.K.A.; Schellenberg, I.; Deubel, A.; Sieverding, E.; Oehl, F. Unexpectedly high diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in fertile Chernozem croplands in Central Europe. Catena 2019, 182, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moturu, U.S.; Nunna, T.; Avula, V.G.; Jagarlamudi, V.R.; Gutha, R.R.; Tamminana, S. Investigating the diversity of bacterial endophytes in maize and their plant growth-promoting attributes. Folia Microbiol. 2023, 68, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpfer, P.; Glaeser, S.P.; McInroy, J.A.; Clermont, D.; Lipski, A.; Criscuolo, A. Neobacillus rhizosphaerae sp. nov., isolated from the rhizosphere, and reclassification of Bacillus dielmonensis as Neobacillus dielmonensis comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 005636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Luo, Y.; Chen, J.; Jin, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Straw return strategies to improve soil properties and crop productivity in a winter wheat-summer maize cropping system. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 133, 126436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauri, P.V.; Silva, C.; Trasante, T.; Acosta, S.; Tió, A.; Lucas, C.; Massa, A.M. Exploration of seed culturable microbiota for the conservation of South American riparian forests. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 6, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.S.; Nguyen, N.T.; Tran, K.T.; Tsuji, K.; Ogo, S. Nitrogen fixation genes from Thermoleptolyngbya sp. Microbes Environ. 2017, 32, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Li, S.; Yan, X. Microbiota in alkaline–sandy soil under fertiliser treatments. Chem. Ecol. 2024, 40, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhou, G.; Chen, L.; Wang, H. Additive quality influences the reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes during chicken manure composting. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 220, 112413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.-K.; Yun, B.-R.; Han, J.-H.; Kim, S.B. Pseudogracilibacillus endophyticus sp. nov., a moderately thermophilic and halophilic species isolated from plant root. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, L.; Dai, J.; Chen, L.; Zeng, G.; Liu, E.; Fang, J. FeSO4 influences phosphorus transport by crucial bacteria during the thermophilic composting phase: Enhancement of phosphorus efficiency. SSRN Preprint 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janarthine, S.R.S.; Eganathan, P. Plant growth promoting of endophytic Sporosarcina aquimarina SjAM16103 isolated from the pneumatophores of Avicennia marina L. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012, 2012, 532060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H. Biostimulant and beyond: Bacillus spp., the Important Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR)-Based Biostimulant for sustainable agriculture. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 9, 1465–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Ramírez, C.E.; Prado-Guzmán, I.S.; Navarrete-Bolaños, J.L.; Ortega, F.V.; García-Rodríguez, Y.M.; Rojas-Solís, D.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.C. Analysis of novel volatile compounds and genomic features of the endophyte Bacillus velezensis ITCE1. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 140, 102867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Etesami, H.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma: A multifunctional agent in plant health and microbiome interactions. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruščić, K.; Jelušić, A.; Hladnik, M.; Janakiev, T.; Anđelković, J.; Bandelj, D.; Dimkić, I. The Influence of Bacterial Inoculants and a Biofertilizer on Maize Cultivation and the Associated Shift in Bacteriobiota During the Growing Season. Plants 2025, 14, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, G.; Dong, Q.G. Bacterial network modularization and crop yields. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2021, 57, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ruan, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y. Microbial interaction patterns in lake sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | Salamanca (Productive Soil) | Villagrán (Non-Productive Soil) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Textural class | – | Clay | Clay |

| Saturation point | % | 68 | 60 |

| Field capacity | % | 36.65 | 32.10 |

| Permanent wilting point | % | 21.70 | 19.10 |

| Hydraulic conductivity | cm·h−1 | 0.60 | 0.28 |

| Bulk density | g·cm−3 | 1.13 | 1.24 |

| Organic matter | % | 5.22 | 2.40 |

| Phosphorus (P-Bray) | ppm | 38.9 | 38.6 |

| Potassium (K) | ppm | 552 | 501 |

| Calcium (Ca) | ppm | 3892 | 4243 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | ppm | 858 | 532 |

| Sodium (Na) | ppm | 230 | 754 |

| Iron (Fe) | ppm | 12.7 | 8.15 |

| Zinc (Zn) | ppm | 0.56 | 0.32 |

| Manganese (Mn) | ppm | 36.1 | 8.90 |

| Copper (Cu) | ppm | 0.93 | 0.64 |

| Boron (B) | ppm | 0.69 | 2.57 |

| Sulfur (S) | ppm | 4.22 | 14.6 |

| Nitrate (N-NO3) | ppm | 14.9 | 5.36 |

| pH (1:2 soil–water) | – | 6.83 | 8.66 |

| Total carbonates | % | 0.01 | 1.70 |

| Year | Maize—Productive Soil | Maize—Non-Productive Soil | Wheat—Productive Soil | Wheat—Non-Productive Soil |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 16,360 | 13,280 | 7390 | 5690 |

| 2021 | 13,160 | 11,125 | 7840 | 6450 |

| 2022 | 14,590 | 12,135 | 7670 | 6590 |

| 2023 | 15,900 | 10,128 | 8050 | 7940 |

| 2024 | 12,890 | 10,380 | 7470 | 6140 |

| Mean annual yield | 14,580 ± 1564 a | 11,410 ± 1305 b | 7684 ± 270 a | 6562 ± 844 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cano-Serrano, S.; Castelán-Sánchez, H.G.; Oyaregui-Cabrera, H.; Hernández, L.G.; Pérez-Pérez, M.C.; Santoyo, G.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.d.C. Assessment of Bacterial Diversity and Rhizospheric Community Shifts in Maize (Zea mays L.) Grown in Soils with Contrasting Productivity Levels. Plants 2026, 15, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010130

Cano-Serrano S, Castelán-Sánchez HG, Oyaregui-Cabrera H, Hernández LG, Pérez-Pérez MC, Santoyo G, Orozco-Mosqueda MdC. Assessment of Bacterial Diversity and Rhizospheric Community Shifts in Maize (Zea mays L.) Grown in Soils with Contrasting Productivity Levels. Plants. 2026; 15(1):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010130

Chicago/Turabian StyleCano-Serrano, Sebastian, Hugo G. Castelán-Sánchez, Helen Oyaregui-Cabrera, Luis G. Hernández, Ma. Cristina Pérez-Pérez, Gustavo Santoyo, and Ma. del Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda. 2026. "Assessment of Bacterial Diversity and Rhizospheric Community Shifts in Maize (Zea mays L.) Grown in Soils with Contrasting Productivity Levels" Plants 15, no. 1: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010130

APA StyleCano-Serrano, S., Castelán-Sánchez, H. G., Oyaregui-Cabrera, H., Hernández, L. G., Pérez-Pérez, M. C., Santoyo, G., & Orozco-Mosqueda, M. d. C. (2026). Assessment of Bacterial Diversity and Rhizospheric Community Shifts in Maize (Zea mays L.) Grown in Soils with Contrasting Productivity Levels. Plants, 15(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010130