Influence of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Soybean Growth and Yield: A Metabarcoding Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

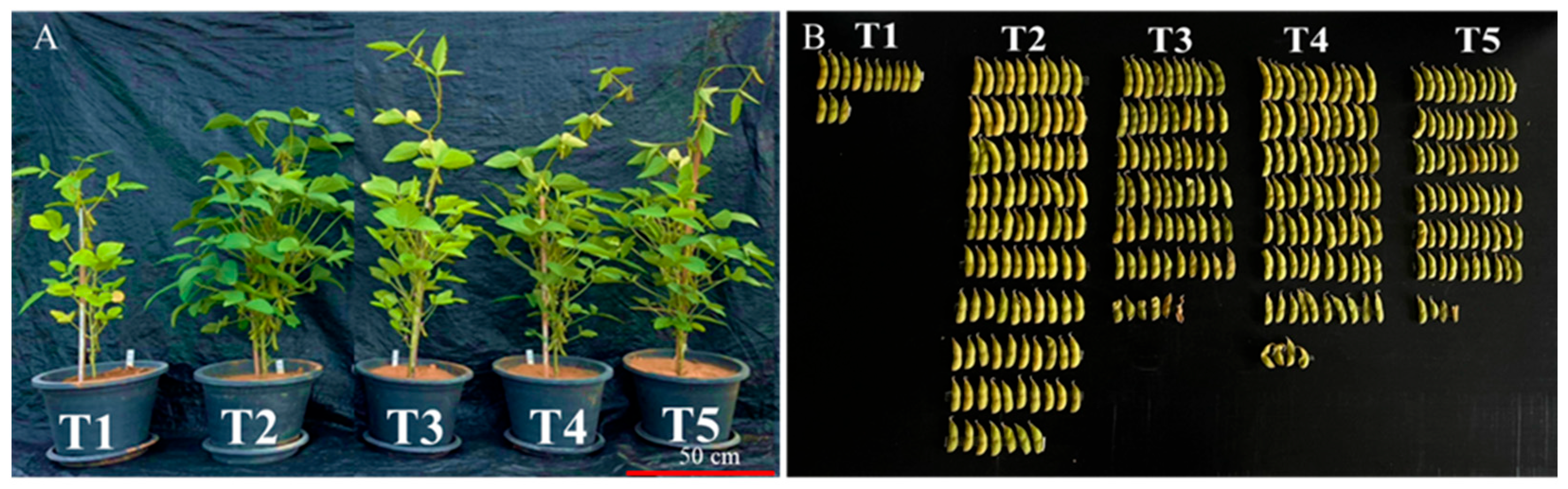

2.1. Plant Growth and Photosynthetic Performance

2.2. Effects of AMF on Biomass, Pod Yield, and Nodules of Soybean

2.3. Protein Concentration and Phytochemicals in Soybean Seeds

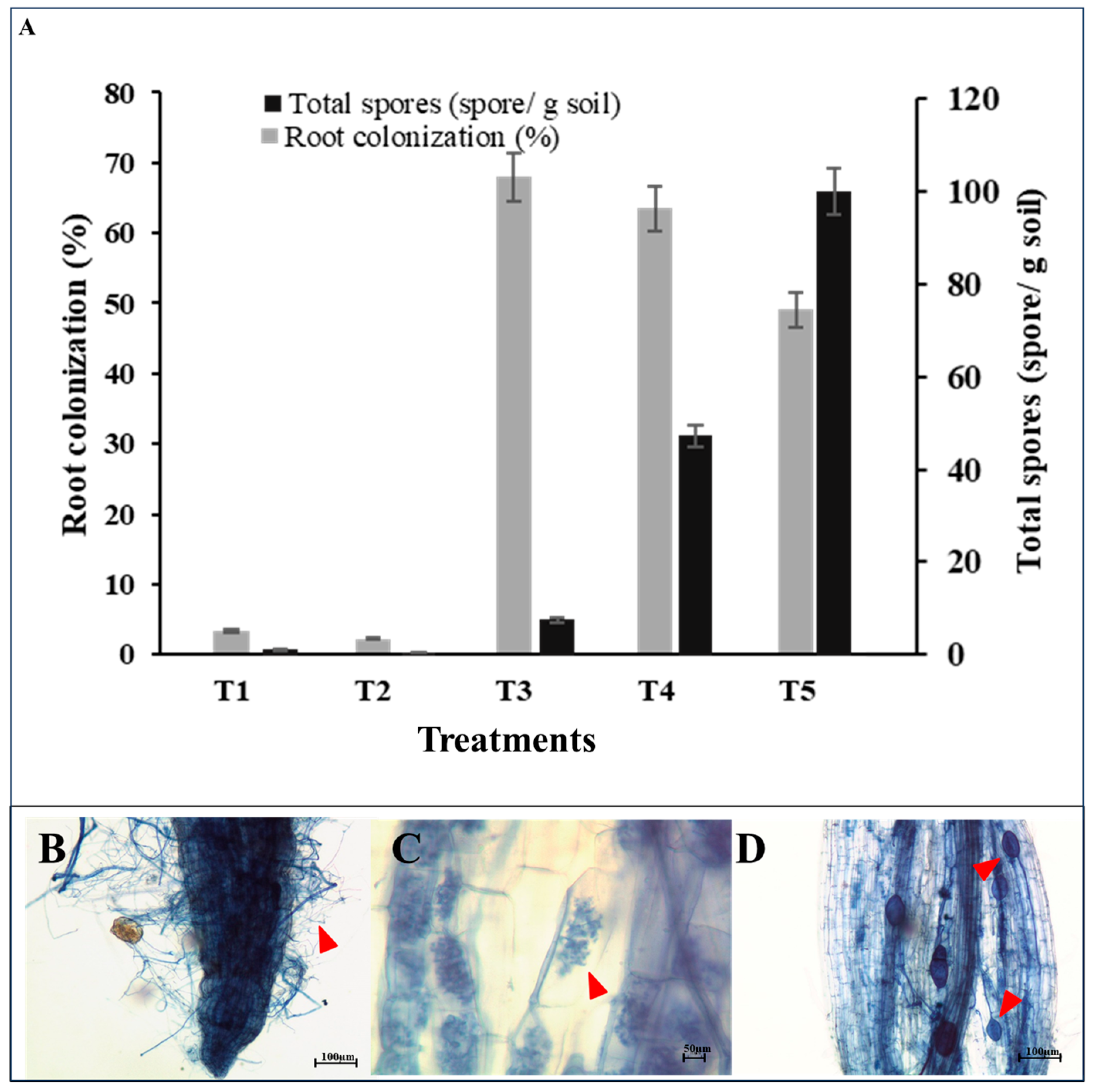

2.4. Root Colonization and Spore Density

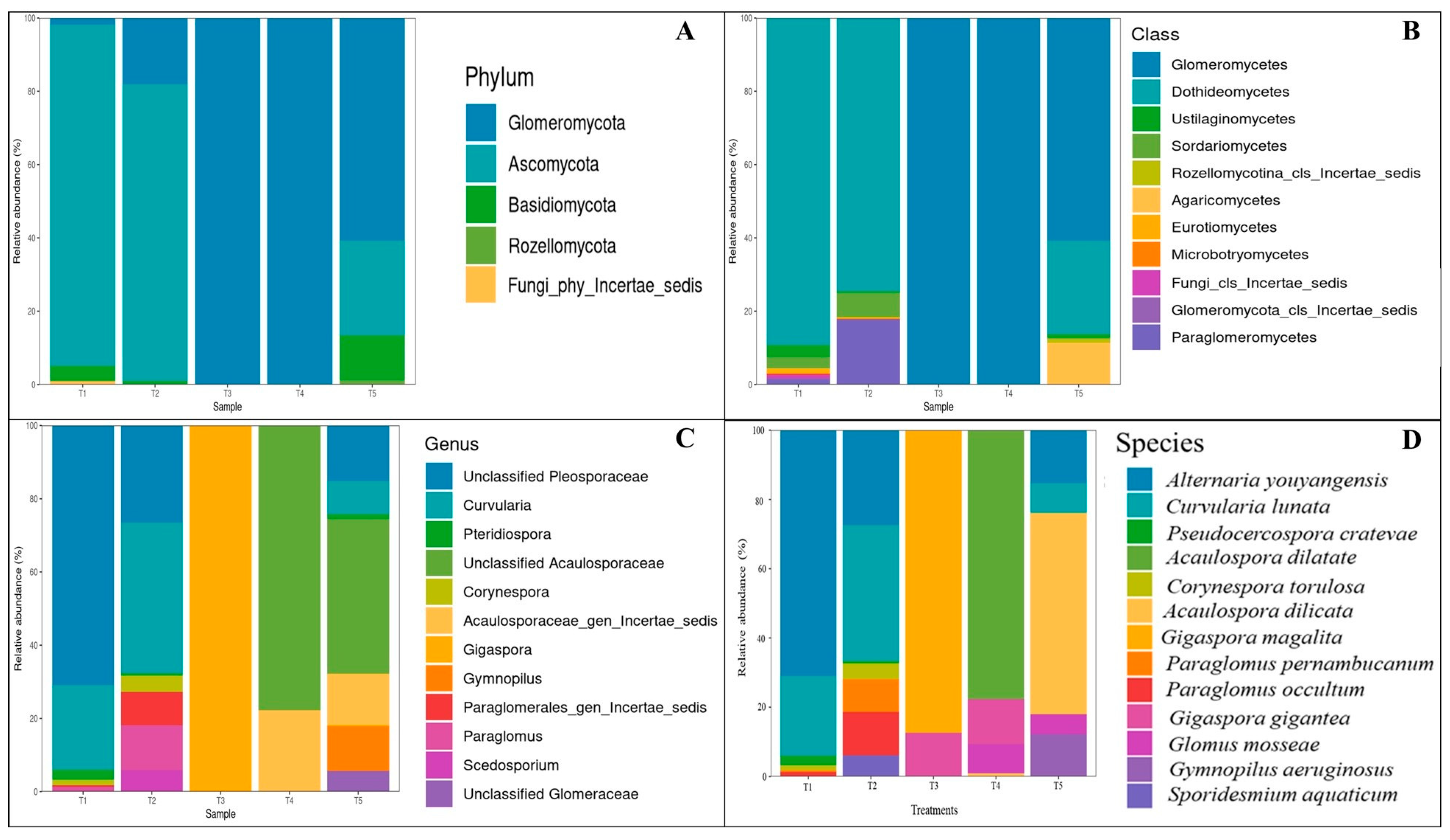

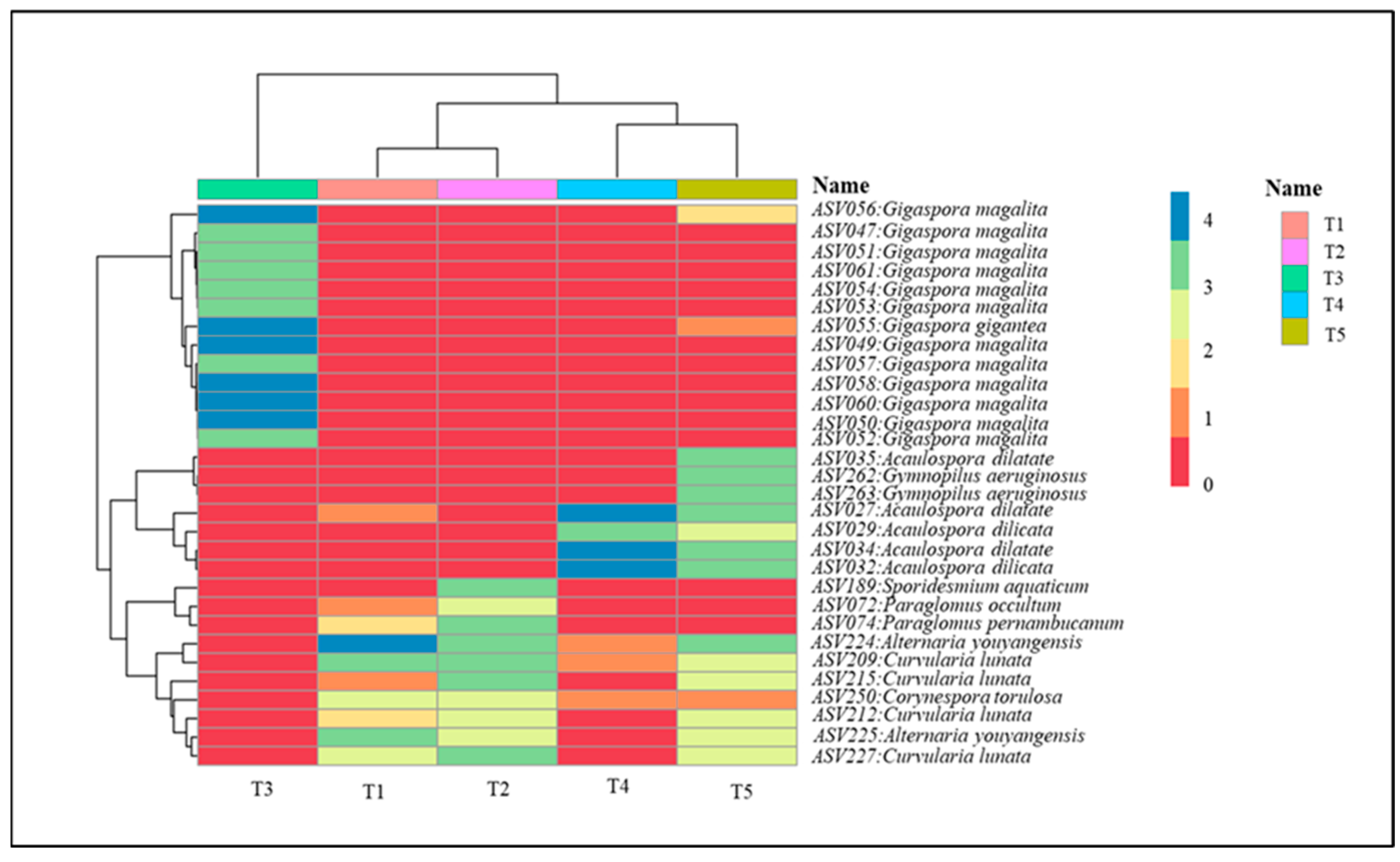

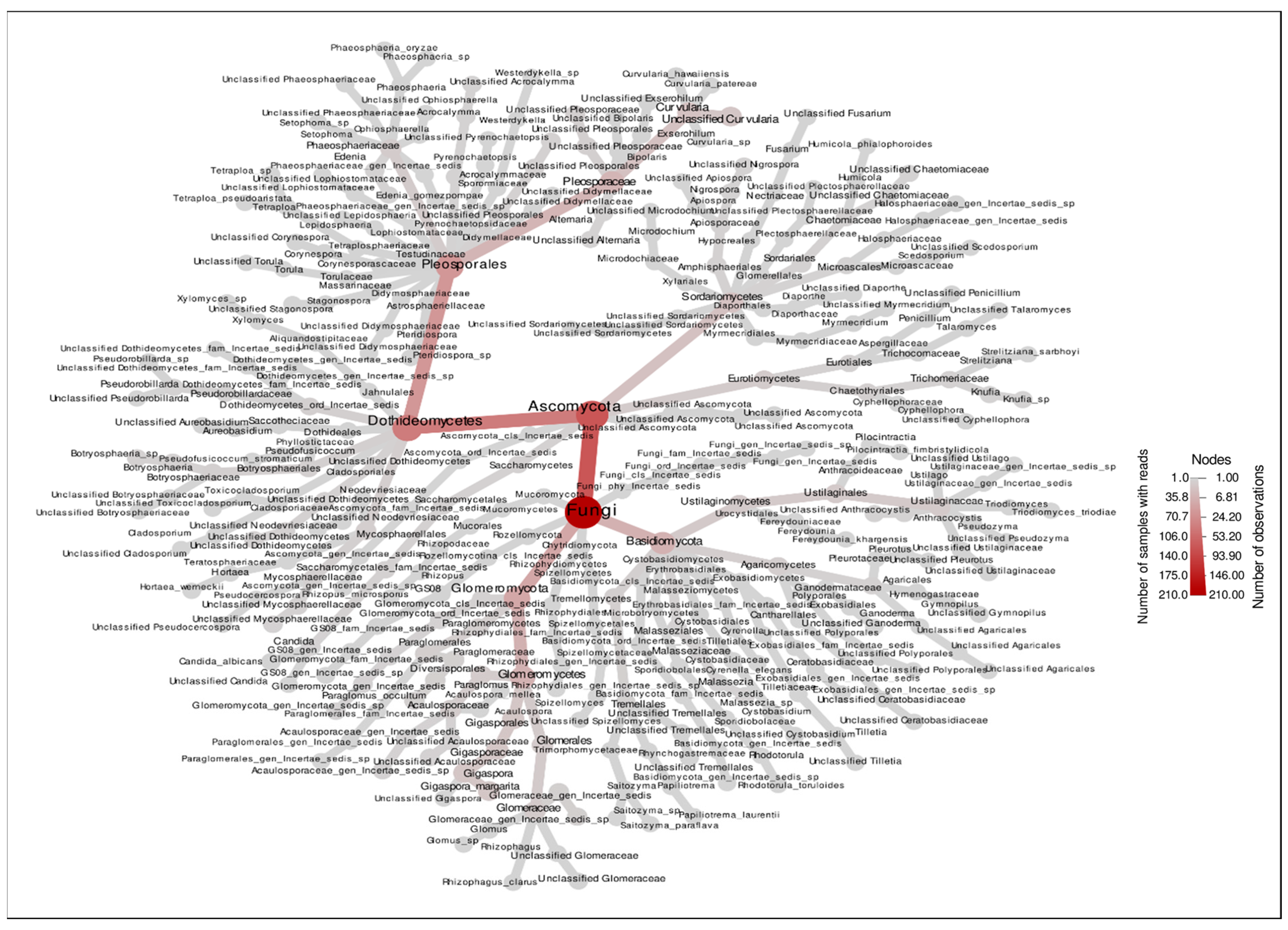

2.5. Fungal Community Analysis

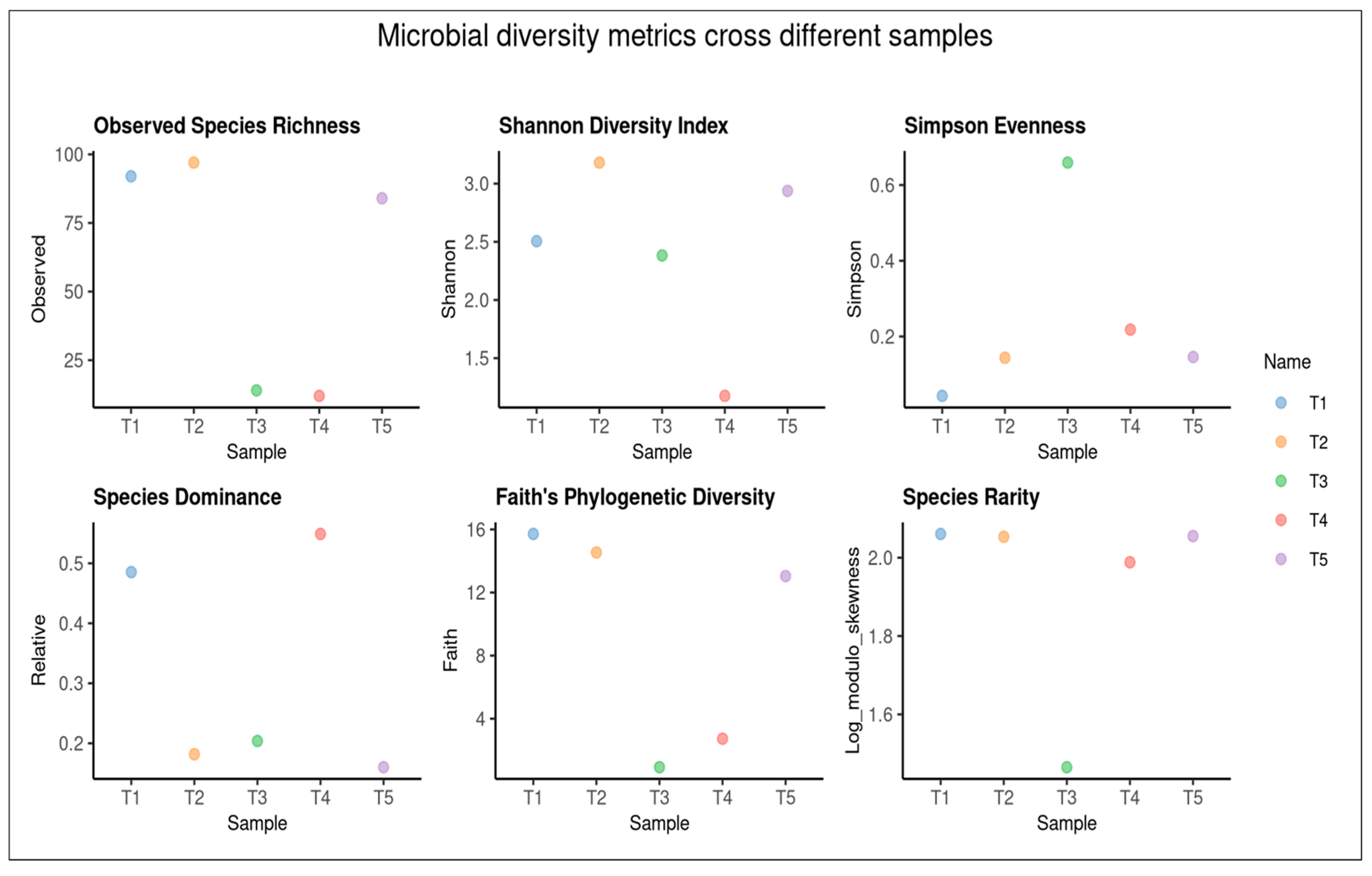

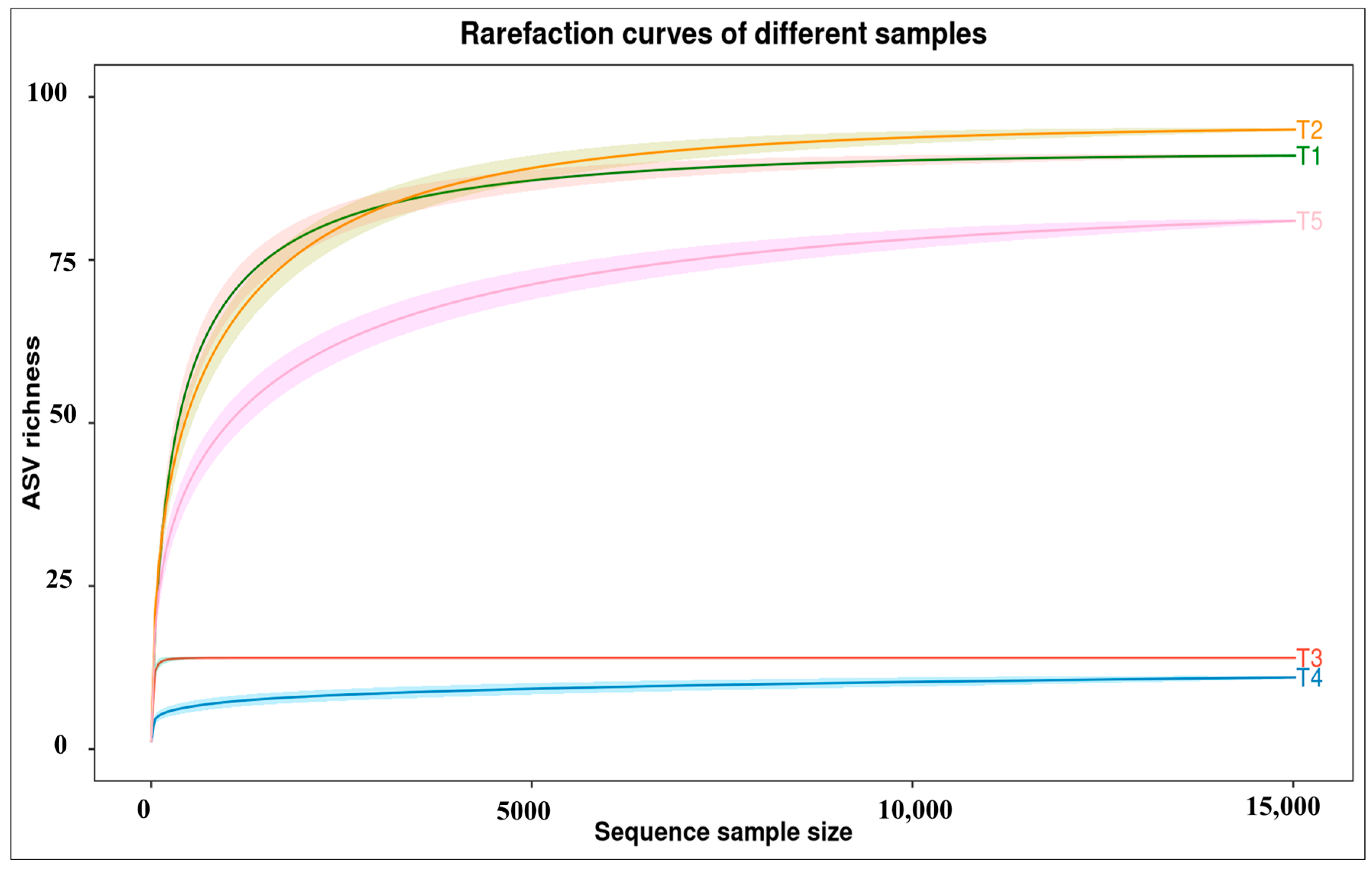

2.6. Alpha Diversity of Fungal Metabarcoding

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. AMF Preparation

4.2. Soil Preparation

4.3. Soybean Preparation

4.4. Experimental Design

4.5. Plant Performance

4.6. Phytochemical Analysis of Soybean Seeds

4.7. Total Protein Content

4.8. Determination of Root Colonization and Total Number of AMF Spores

4.9. Fungal Community Analysis

4.9.1. Extraction of DNA and Sequencing

4.9.2. Bioinformatics

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jung, J.W.; Park, S.Y.; Oh, S.D.; Jang, Y.; Suh, S.J.; Park, S.K.; Ha, S.H.; Park, S.U.; Kim, J.K. Metabolomic variability of different soybean genotypes: β-Carotene-enhanced (Glycine max), wild (Glycine soja), and hybrid (Glycine max × Glycine soja) soybeans. Foods 2021, 10, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooyandeh, H. Soy products as healthy and functional foods. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2011, 7, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.S. Current perspectives on the beneficial effects of soybean isoflavones and their metabolites for humans. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Shin, B.K.; Seo, J.A.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, D.Y.; Choi, H.K. Discrimination of the geographical origin of soybeans using NMR-based metabolomics. Foods 2021, 10, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandini; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R.; Prakash, O. The impact of chemical fertilizers on our environment and ecosystem. In Research Trends in Environmental Sciences, 2nd ed.; Mittal Publications: New Delhi, India, 2019; pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Seemakram, W.; Paluka, J.; Suebrasri, T.; Lapjit, C.; Kanokmedhakul, S.; Kuyper, T.W.; Ekprasert, J.; Boonlue, S. Enhancement of growth and cannabinoids content of hemp (Cannabis sativa) using arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 845794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonlue, S.; Surapat, W.; Pukahuta, C.; Suwanarit, P.; Suwanarit, A.; Morinaga, T. Diversity and efficiency of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in soils from organic chili (Capsicum frutescens L.) farms. Mycoscience 2012, 53, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemakram, W.; Suebrasri, T.; Khaekhum, S.; Ekprasert, J.; Aimi, T.; Boonlue, S. Growth enhancement of the highly prized tropical trees Siamese rosewood and Burma padauk. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacoon, S.; Ekprasert, J.; Riddech, N.; Mongkolthanaruk, W.; Jogloy, S.; Vorasoot, N.; Cooper, J.; Boonlue, S. Growth enhancement of sunchoke by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under drought condition. Rhizosphere 2021, 17, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentpéteri, V.; Virág, E.; Mayer, Z.; Duc, N.H.; Hegedűs, G.; Posta, K. First peek into the transcriptomic response in heat-stressed tomato inoculated with Septoglomus constrictum. Plants 2024, 13, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacoon, S.; Seemakram, W.; Ekprasert, J.; Theerakulpisut, P.; Sanitchon, J.; Kuyper, T.W.; Boonlue, S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance growth and increase concentrations of anthocyanin, phenolic compounds, and antioxidant activity of black rice (Oryza sativa L.). Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, G.G.; Santana, L.R.; da Silva, L.N.; Teixeira, M.B.; da Silva, A.A.; Cabra, J.S.R.; Souchie, E.L. Morpho-physiological traits of soybean plants in symbiosis with Gigaspora sp. and submitted to water restriction. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudin, M.; Nelvia, N.; Deviona, D. Growth and yield of soybean plants (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) in podsolic soil with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and synthetic zeolite from fly ash as soil amendments. Devotion J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 4, 2240–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustini, L.; Irianto, R.S.B.; Indrayadi, H.; Tanna, R.D.; Faulina, S.A.; Turjaman, M.; Hidayat, A.; Tjahjono, B.; Priatna, D. The effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation on growth and survivability of micropropagated Eucalyptus pellita and Acacia crassicarpa in nursery. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 533, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virág, E.; Hegedűs, G.; Nagy, Á.; Pallos, J.P.; Kutasy, B. Temporal shifts in hormone signaling networks orchestrate soybean floral development under field conditions: An RNA-Seq Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, M.J.; Azcón-Aguilar, C. Unraveling mycorrhiza-induced resistance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.C.; Martinez-Medina, A.; Lopez-Raez, J.A.; Pozo, M.J. Mycorrhiza-induced resistance and priming of plant defenses. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012, 38, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Qin, C.; Ahanger, M.A.; Raza, S.; Khan, M.I.; Ashraf, M.; Ahmed, N.; Zhang, L. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: Implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Yang, M.; Fazal, A.; Han, H.; Lin, H.; Yin, T.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, S.; Niu, K.; Sun, S.; et al. Harnessing the power of microbes: Enhancing soybean growth in an acidic soil through AMF inoculation rather than P-fertilization. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngosong, C.; Tatah, B.N.; Olougou, M.N.E.; Suh, C.; Nkongho, R.N.; Ngone, M.A.; Achiri, D.T.; Tchakounté, G.V.T.; Ruppe, S. Inoculating plant growth-promoting bacteria and arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi modulates rhizosphere acid phosphatase and nodulation activities and enhances the productivity of soybean (Glycine max). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 934339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marro, N.; Cofré, N.; Grilli, G.; Alvarez, C.; Labuckas, D.; Maestri, D.; Urcelay, C. Soybean yield, protein content and oil quality in response to interaction of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and native microbial populations from mono- and rotation-cropped soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 152, 103575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Molotla, I.A.; Félix-Gastélum, R.; Leyva-Madrigal, K.Y.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Maldonado-Mendoza, I.E. Etiology of soybean (Glycine max) leaf spot in Sinaloa, Mexico. Mex. J. Phytopathol. 2021, 39, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Machado, C.; Bogaj, V.; Papp, V.; Balázs, G.; Papp, D. Alternaria and Curvularia leaf spot pathogens show high aggressivity on watermelon, and are emerging pathogens in cucurbit production. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2025, 64, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Walker, C.; Bending, G.D. Dimorphic spore production in the genus Acaulospora. Mycoscience 2014, 55, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, O.X.; Datta, M.S. Microbial interactions and community assembly at microscales. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016, 31, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.G.; Zhang, F.M.; Yang, T.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.G.; Dai, C.C. Endophytic fungus drives nodulation and N2 fixation attributable to specific root exudates. mBio 2019, 10, e00728-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, D.D.; Neal, A.L.; van Wees, S.C.M.; Ton, J. Mycorrhiza-induced resistance: More than the sum of its parts. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.C.; Wilson, G.W.T.; Wilson, J.A.; Miller, R.M.; Bowker, M.A. Mycorrhizal phenotypes and the law of the minimum. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirkell, T.J.; Pastok, D.; Field, K.J. Carbon for nutrient exchange between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and wheat varies according to cultivar and fungal species. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 2318–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Martin, F.M.; Selosse, M.A.; Sanders, I.R. Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: The past, the present, and the future. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarathambal, C.; Manimaran, B.; Peeran, M.F.; Srinivasan, V.; Praveena, R.; Gayathri, P.; Dilkush, F.; Abraham, A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization promotes plant growth and regulates biochemical and molecular defense responses against Pythium myriotylum and Meloidogyne incognita in ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.). Rhizosphere 2025, 34, 101071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, A. The effectiveness of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal species (Funneliformis mosseae, Rhizophagus intraradices, and Claroideoglomus etunicatum) in the biocontrol of root and crown rot pathogens, Fusarium solani and Fusarium mixture in pepper. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, B.A.; Skipper, H.D. Method for the recovery and quantitative estimation of propagules from soil. In Methods and Principles of Mycorrhizal Research; Schenck, N.C., Ed.; American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1982; pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.L. Nitrogen determination for soils and plant tissue. In Soil Chemical Analysis; Prentice-Hall of India Private Limited: New Delhi, India, 1967; pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman, G.E.; Stanley, M.A.; Knudsen, D. Automated total nitrogen analysis of soil and plant samples. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. Proc. 1973, 37, 480–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, P.R. A Textbook of Soil Chemical Analysis; Murray: London, UK, 1971; pp. 120–309. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, I.; Adeniyi, A.; Mukaila, T.; Hammed, A. Optimization of soybean protein extraction with ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) using response surface methodology. Foods 2023, 12, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koske, R.E.; Gemma, J.N. A modified procedure for staining roots to detect VA mycorrhizas. Mycol. Res. 1989, 92, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouvelot, A.; Kough, J.; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V. Evaluation of VA infection levels in root systems: Research for estimation methods having a functional significance. In Physiological and Genetical Aspects of Mycorrhizae; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V., Gianinazzi, S., Eds.; INRA Press: Paris, France, 1986; pp. 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Correction in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0252-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beule, L.; Karlovsky, P. Improved normalization of species count data in ecology by scaling with ranked subsampling (SRS): Application to microbial communities. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõljalg, U.; Nilsson, H.R.; Schigel, D.; Tedersoo, L.; Larsson, K.H.; May, T.W.; Taylor, A.F.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Frøslev, T.G.; Lindahl, B.D.; et al. The taxon hypothesis paradigm—On the unambiguous detection and communication of taxa. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Height (cm) | Diameter (mm) | SPAD | Photosynthetic Rate (µmol CO2 m−2 s−1) | Stomatal Conductance (mol H2O m−2 s−1) | Transpiration Rate (mmol H2O m−2 s−1) | Water Use Efficiency (µmol CO2/mmol H2O m−2 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 74.0 b | 3.66 d | 30.6 c | 8.26 d | 0.45 aa | 1.66 a | 5.78 c |

| T2 | 105.3 a | 10.73 a | 41.6 a | 21.03 a | 0.49 a | 1.85 a | 11.90 ac |

| T3 | 95.0 ab | 9.06 ab | 37.0 ab | 15.31 b | 0.502 a | 2.36 a | 7.20 bc |

| T4 | 115.0 a | 8.10 bc | 36.6 abc | 11.74 c | 0.53 a | 2.12 a | 5.86 bc |

| T5 | 112.3 a | 6.83 c | 32.2 cb | 18.85 a | 0.39 a | 1.73 a | 10.87 a |

| %CV. | 12 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 28 | 30 | 29 |

| F-test | ** | ** | * | ** | ns | ns | * |

| Treatments | Number of Pods | Total Seed Weight (g Plant−1) | 100 Seed Weight (g) | Biomass (g Plant−1) | Number of Nodules Plant−1 | Nodules Fresh Weight (g) | Total N (mg g−1) | Total P (mg g−1) | Total K (mg g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 13.7 d | 5.1 c | 10.3 c | 10.5 c | 1.7 b | 0.20 | 1.07 b | 0.80 c | 4.20 b |

| T2 | 97.0 a | 30.0 a | 12.6 ab | 63.8 a | 4.7 b | 0.8 d | 8.00 a | 2.80 a | 8.70 a |

| T3 | 66.3 c | 15.1 b | 10.6 bc | 32.9 b | 8.3 b | 1.9 c | 6.80 a | 1.40 b | 6.60 ab |

| T4 | 74.0 b | 14.06 b | 13.07 a | 36.5 b | 9.7 b | 2.2 b | 5.90 a | 1.00 b | 7.30 a |

| T5 | 64.3 c | 14.5 b | 13.1 a | 34.2 b | 22.3 a | 5.8 a | 6.90 a | 1.40 b | 6.90 ab |

| %CV. | 5 | 12 | 10 | 16 | 24 | 14 | 18 | 12 | 11 |

| F-test | ** | ** | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ns |

| Treatments | Total Protein (mg g−1) | Total Phenolic Compound (mg Gallic eq 100 g−1 DW) | Antioxidant (% Radical Scavenging) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 452 c | 126.1 bc | 29.3 c |

| T2 | 401 d | 112.3 c | 44.4 bc |

| T3 | 522 a | 196.5 a | 33.1 bc |

| T4 | 494 b | 175.3 a | 60.2 ab |

| T5 | 496 b | 167.0 ab | 72.1 a |

| %CV. | 23 | 15 | 25 |

| F-test | ** | ** | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Seemakram, W.; Suebrasri, T.; Chankaew, S.; Boonlue, S. Influence of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Soybean Growth and Yield: A Metabarcoding Approach. Plants 2026, 15, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010131

Seemakram W, Suebrasri T, Chankaew S, Boonlue S. Influence of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Soybean Growth and Yield: A Metabarcoding Approach. Plants. 2026; 15(1):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010131

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeemakram, Wasan, Thanapat Suebrasri, Sompong Chankaew, and Sophon Boonlue. 2026. "Influence of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Soybean Growth and Yield: A Metabarcoding Approach" Plants 15, no. 1: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010131

APA StyleSeemakram, W., Suebrasri, T., Chankaew, S., & Boonlue, S. (2026). Influence of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Soybean Growth and Yield: A Metabarcoding Approach. Plants, 15(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010131