Streptomyces Volatiles Alter Auxin/Cytokinin Signaling, Root Architecture, and Growth Rate in Arabidopsis thaliana via Signaling Through the KISS ME DEADLY Gene Family

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

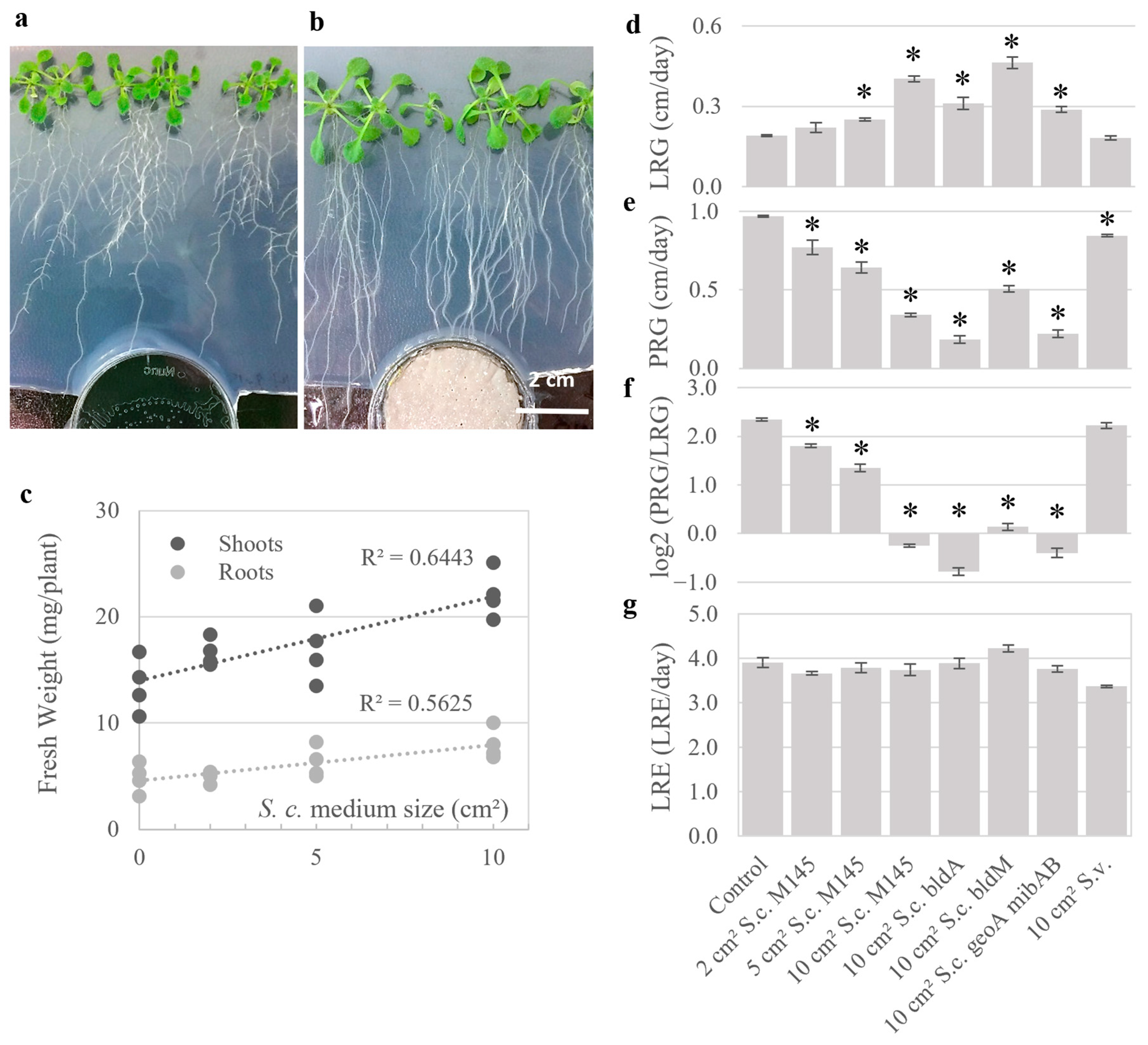

2.1. Bacterial Volatiles Enhance Tissue Expansion and Modify Root Architecture in Seedlings

2.2. Seedling Growth Is Modified by Volatiles Independent of Bacterial Developmental Stage

2.3. Screening of Volatiles from Different Isolates

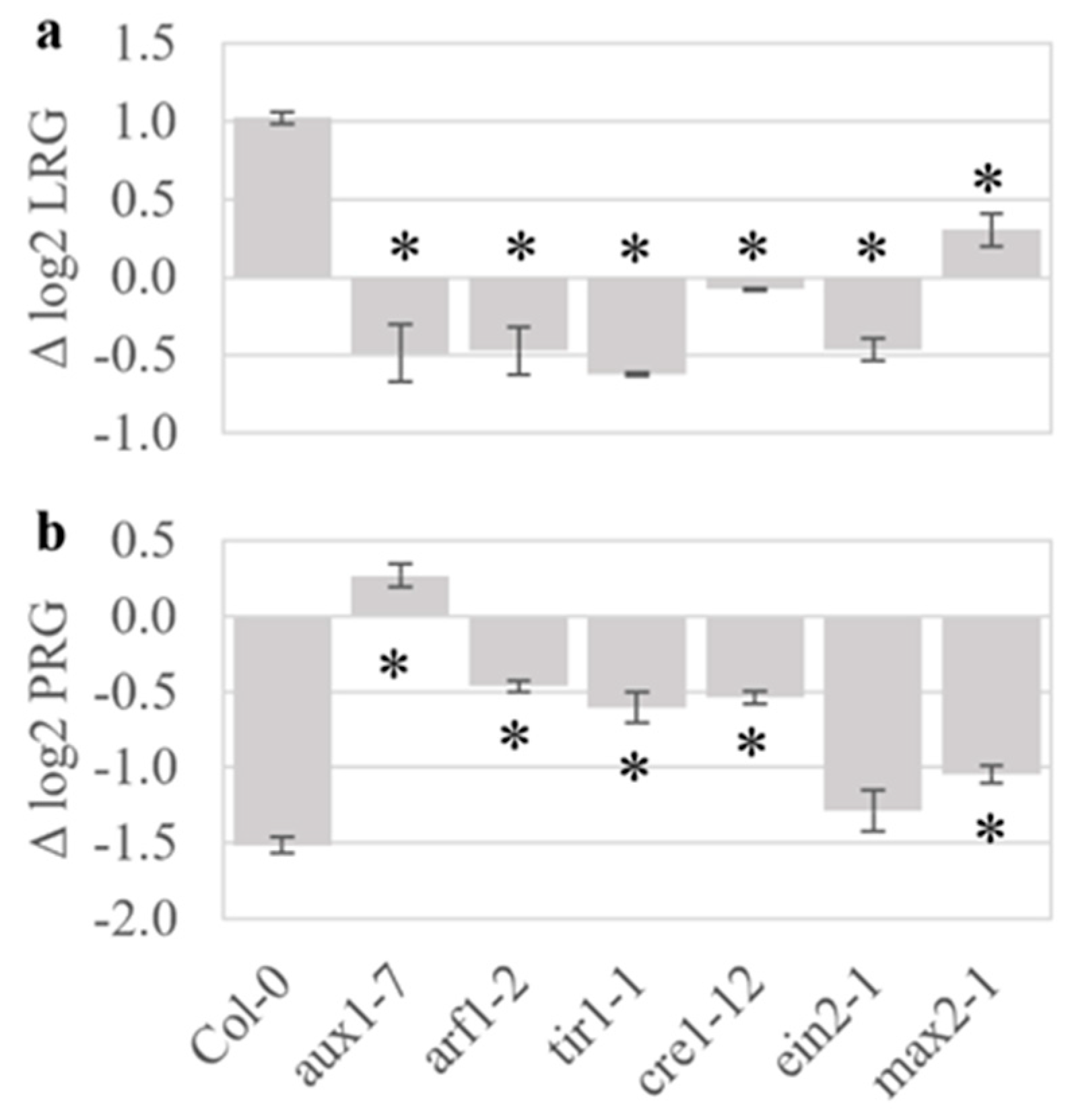

2.4. Plant Hormone Mutants Have Altered Responses to Volatiles

2.5. The Plant Response to Bacterial Volatiles Shows Similarity to Other Biotic Responses

2.6. Gene Ontology Analysis of RNA-Seq Data Identifies Initial Plant Reprogramming Components

2.7. Transgenic Plants Deficient in KMD and Associated Cytokinin Response Proteins Are Unresponsive to Volatiles

2.8. The Root Growth Response Elicited by the Bioactive Volatile 3-Octanone Depends on KMD and Auxin/Cytokinin Homeostasis

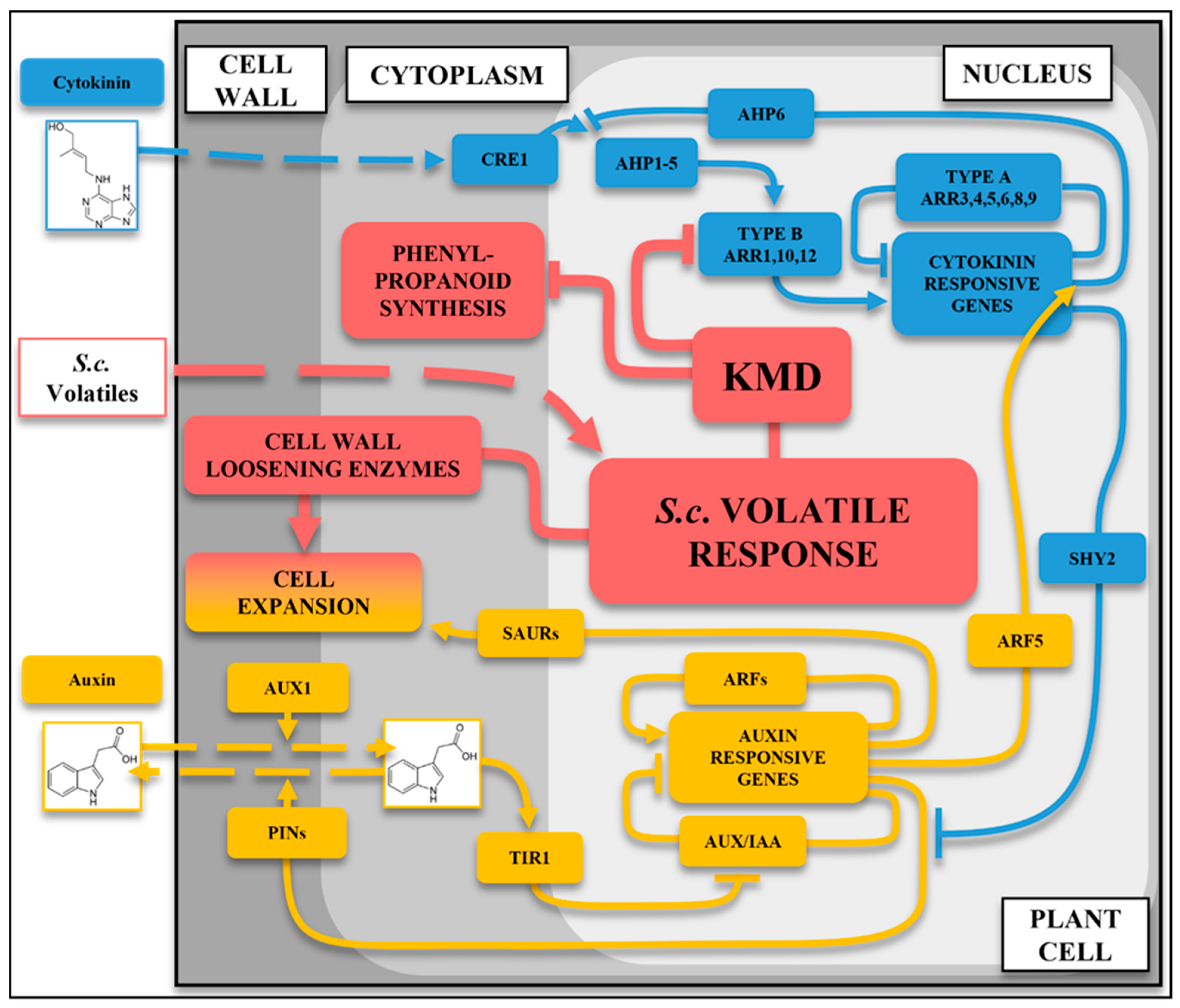

2.9. Integrated Model of the Volatile Response Pathway

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Methods

5.1. Plant Growth System

5.2. Bacterial Growth

5.3. Analysis of Tissue Growth

5.4. Volatile Collection and Analyses

5.5. RNA Extraction

5.6. Analysis of RNA-Seq Data

5.7. qRT-PCR Confirmation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gruntman, M.; Groß, D.; Májeková, M.; Tielbörger, K. Decision-making in plants under competition. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segundo-Ortin, M.; Calvo, P. Consciousness and cognition in plants. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2022, 13, e1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Segundo-Ortin, M.; Calvo, P. Decision making in plants: A rooted perspective. Plants 2023, 12, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuman, M.C.; Baldwin, I.T. The layers of plant responses to insect herbivores. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2016, 61, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dener, E.; Kacelnik, A.; Shemesh, H. Pea plants show risk sensitivity. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1763–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, P.; Ali, N.; Saini, S.; Pati, P.K.; Pati, A.M. Physiological and molecular insight of microbial biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1041413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Salem, H.M.; Ahmed, A.I.; Mahmood, M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Ebrahim, A.A.M.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Negm, S.H.; et al. Plant growth-promoting microorganisms as biocontrol agents of plant diseases: Mechanisms, challenges and future perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 923880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.M.; Ameye, M.; Devlieghere, F.; De Saeger, S.; Eeckhout, M.; Audenaert, K. Streptomyces strains promote plant growth and induce resistance against Fusarium verticillioides via transient regulation of auxin signaling and archetypal defense pathways in maize plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 755733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, J.; Kolnaar, R.; Ravensberg, W.J. Mode of action of microbial biological control agents against plant diseases: Relevance beyond efficacy. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 454982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaene, T.; Langendries, S.; Beirinckx, S.; Maes, M.; Goormachtig, S. Streptomyces as a plant’s best friend? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Kang, H.; Peng, Q.; Wicaksono, W.A.; Berg, G.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhang, D.; Cernava, T.; Liu, Y. Microbiome homeostasis on rice leaves is regulated by a precursor molecule of lignin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, G.E.; Bishopp, A.; Kieber, J.J. The yin-yang of hormones: Cytokinin and auxin interactions in plant development. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backer, R.; Rokem, J.S.; Ilangumaran, G.; Lamont, J.; Praslickova, D.; Ricci, E.; Subramanian, S.; Smith, D.L. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: Context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization of biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, R.; Ryu, C.-M. Revisiting bacterial volatile-mediated plant growth promotion: Lessons from the past and objectives for the future. Ann. Bot. 2018, 122, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.L.; Hermosa, R.; Lorito, M.; Monte, E. Trichoderma: A multipurpose, plant-beneficial microorganism for eco-sustainable agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglione, A.M.; Mannino, G.; Contartese, V.; Bertea, C.M.; Ertani, A. Microbial biostimulants as response to modern agriculture needs: Composition, role and application of these innovative products. Plants 2021, 10, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmagnani, A.S.; Kanchiswamy, C.N.; Paponov, I.A.; Bossi, S.; Malnoy, M.; Maffei, M.E. Bacterial volatiles (mVOC) emitted by the phytopathogen Erwinia amylovora promote Arabidopsis thaliana growth and oxidative stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kim, M.; Krishnamachari, V.; Payton, P.; Sun, Y.; Grimson, M.; Farag, M.A.; Ryu, C.; Allen, R.; Melo, I.S.; et al. Rhizobacterial volatile emissions regulate auxin homeostasis and cell expansion in Arabidopsis. Planta 2007, 226, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.A.S.; Gu, Q.; Wu, H.; Raza, W.; Hanif, A.; Wu, L.; Colman, M.V.; Gao, X. Plant growth promotion by volatile organic compounds produced by Bacillus subtilis SYST2. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hung, R.; Yap, M.; Bennett, J.W. Age matters: The effects of volatile organic compounds emitted by Trichoderma atroviride on plant growth. Arch. Microbiol. 2015, 197, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, D.; Fabbri, C.; Connor, E.C.; Schiestl, F.P.; Klauser, D.R.; Boller, T.; Eberl, L.; Weisskopf, L. Production of plant growth modulating volatiles is widespread among rhizosphere bacteria and strongly depends on culture conditions. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 3047–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincheira, P.; Quiroz, A. Microbial volatiles as plant growth inducers. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 208, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Chiang, Y.; Kieber, J.J.; Schaller, G.E. SCF(KMD) controls cytokinin signaling by regulating the degradation of type-B response regulators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 10028–10033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, E.; Triana, M.R.; Kubasi, S.; Blum, S.; Paz-Ares, J.; Rubio, V.; Weiss, D. KISS-ME-DEADLY F-box proteins modulate cytokinin responses by targeting the transcription factor TCP14 for degradation. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kieber, J.J.; Schaller, G.E. The rice F-box protein KISS ME DEADLY2 functions as a negative regulator of cytokinin signaling. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e26434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordovez, V.; Carrion, V.J.; Etalo, D.W.; Mumm, R.; Zhu, H.; van Wezel, G.P.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Diversity and functions of volatile organic compounds produced by Streptomyces from a disease-suppressive soil. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottier, F.; Mühlschlegel, F.A. Communication in fungi. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012, 2012, 351832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Jacobo, M.F.; Steyaert, J.M.; Salazar-Badillo, F.B.; Nguyen, D.V.; Rostás, M.; Braithwaite, M.; De Souza, J.T.; Jimenez-Bremont, J.F.; Ohkura, M.; Stewart, A.; et al. Environmental growth conditions of Trichoderma spp. affects indole acetic acid derivatives, volatile organic compounds, and plant growth promotion. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa-Becerra, R.; Desgarennes, D.; Molina-Torres, J.; Ramírez-Chávez, E.; Kiel-Martínez, A.L.; Carrión, G.; Ortiz-Castro, R. Plant growth-promoting and non-promoting rhizobacteria from avocado trees differentially emit volatiles that influence growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. Protoplasma 2022, 259, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.-M.; Farag, M.A.; Hu, C.-H.; Reddy, M.S.; Kloepper, J.W.; Paré, P.W. Bacterial volatiles induce systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenke, K.; Wanke, D.; Kilian, J.; Berendzen, K.; Harter, K.; Piechulla, B. Volatiles of two growth-inhibiting rhizobacteria commonly engage AtWRKY18 function. Plant J. 2012, 70, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacquard, S.; Kracher, B.; Hiruma, K.; Münch, P.C.; Garrido-Oter, R.; Thon, M.R.; Weimann, A.; Damm, U.; Dallery, J.-F.; Hainaut, M.; et al. Survival trade-offs in plant roots during colonization by closely related beneficial and pathogenic fungi. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majda, M.; Robert, S. The role of auxin in cell wall expansion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruz, T.; Laule, O.; Szabo, G.; Wessendorp, F.; Bleuler, S.; Oertle, L.; Widmayer, P.; Gruissem, W.; Zimmermann, P. Genevestigator v3: A reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv. Bioinform. 2008, 2008, 420747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eden, E.; Navon, R.; Steinfeld, I.; Lipson, D.; Yakhini, Z. GOrilla: A tool for discovery and visualization of enriched go terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbon, S.; Ireland, A.; Mungall, C.J.; Shu, S.; Marshall, B.; Lewis, S. AmiGO Hub and Web Presence Working Group. AmiGO: Online access to ontology and annotation data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cai, X.; Wei, H.; Zhang, L.; Dong, A.; Su, W. Histone methylation readers MRG1/MRG2 interact with the transcription factor TCP14 to positively modulate cytokinin sensitivity in Arabidopsis. J. Genet. Genom. 2023, 50, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Gou, M.; Liu, C.-J. Arabidopsis kelch repeat F-box proteins regulate phenylpropanoid biosynthesis via controlling the turnover of PHENYLALANINE AMMONIA-LYASE. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4994–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.; Muhammad, S.; Jin, W.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Munir, R.; et al. Modulating root system architecture: Cross-talk between auxin and phytohormones. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1343928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, L.; Ruffley, M.; Exposito-Alonso, M. Planting genomes in the wild: Arabidopsis from genetics history to the ecology and evolutionary genomics era. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2025, 76, 605–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.K.; McClure, R.; Egbert, R.G. Soil microbiome engineering for sustainability in a changing environment. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1716–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacheron, J.; Desbrosses, G.; Bouffaud, M.-L.; Touraine, B.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Muller, D.; Legendre, L.; Wisniewski-Dyé, F.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleery, W.T.; Mohd-Radzman, N.A.; Grieneisen, V.A. Root branching plasticity: Collective decision-making results from local and global signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017, 44, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splivallo, R.; Novero, M.; Bertea, C.M.; Bossi, S.; Bonfante, P. Truffle volatiles inhibit growth and induce an oxidative burst in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2007, 175, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbeva, P.; Hordijk, C.; Gerards, S.; de Boer, W. Volatiles produced by the mycophagous soil bacterium Collimonas. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 87, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, T.; Kimura, T.; Tanaka, H.; Kaneko, S.; Ichii, S.; Kiuchi, M.; Suzuki, T. Analysis of volatile metabolites emitted by soil-derived fungi using head space solid-phase microextraction/gas chromatography/mass spectrometry: I. Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus nidulans, Fusarium solani and Penicillium paneum. Surf. Interface Anal. 2012, 44, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kües, U.; Khonsuntia, W.; Subba, S.; Dörnte, B. Volatiles in communication of Agaricomycetes. Physiol. Genet. 2018, 15, 149–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druzhinina, I.S.; Seidl-Seiboth, V.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Horwitz, B.A.; Kenerley, C.M.; Monte, E.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Zeilinger, S.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Kubicek, C.P. Trichoderma: The genomics of opportunistic success. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitarra, G.S.; Abee, T.; Rombouts, F.M.; Posthumus, M.A.; Dijksterhuis, J. Germination of Penicillium paneum conidia is regulated by 1-octen-3-ol, a volatile self-inhibitor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 2823–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Behringer, G.; Hung, R.; Bennett, J. Effects of fungal volatile organic compounds on Arabidopsis thaliana growth and gene expression. Fungal Ecol. 2019, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellosillo, T.; Martínez, M.; López, M.A.; Vicente, J.; Cascón, T.; Dolan, L.; Hamberg, M.; Castresana, C. Oxylipins produced by the 9-lipoxygenase pathway in Arabidopsis regulate lateral root development and defense responses through a specific signaling cascade. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.J.; Mahoney, N.E.; Cook, D.; Gee, W.S. Generation of the volatile spiroketals conophthorin and chalcogran by fungal spores on polyunsaturated fatty acids common to almonds and pistachios. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11869–11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzenberger, M.; Grosch, W. Origin of the oxygen in the products of the enzymatic cleavage reaction of linoleic acid to 1-octen-3-ol and 10-oxo-trans-8-decenoic acid in mushrooms (Psalliota bispora). Biochim. Biophys. Acta Lipids Lipid Metab. 1984, 794, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieser, T.; Bibb, M.J.; Buttner, M.J.; Chater, K.F.; Hopwood, D.A. Practical Streptomyces Genetics; The John Innes Foundation: Norwich, UK, 2000; p. 613. [Google Scholar]

- Prabakaran, M.; Lee, K.-J.; An, Y.; Kwon, C.; Kim, S.; Yang, Y.; Ahmad, A.; Kim, S.-H.; Chung, I.-M. Changes in soybean (Glycine max L.) flour fatty-acid content based on storage temperature and duration. Molecules 2018, 23, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidorov, V.; Jdanova, M. Volatile organic compounds from leaves litter. Chemosphere 2002, 48, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurepa, J.; Shull, T.E.; Karunadasa, S.S.; Smalle, J.A. Modulation of auxin and cytokinin responses by early steps of the phenylpropanoid pathway. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmassry, M.M.; Farag, M.A.; Preissner, R.; Gohlke, B.-O.; Piechulla, B.; Lemfack, M.C. Sixty-one volatiles have phylogenetic signals across bacterial domain and fungal kingdom. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 557253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennerman, K.K.; Yin, G.; Bennett, J.W. Eight-carbon volatiles: Prominent fungal and plant interaction compounds. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, B.R.; Soltan, D.; Schmidt, J.; Areskoug, M.; Rabe, K.; Swart, C.; Widell, S.; Rasmusson, A.G. The antibiotic peptaibol alamethicin from Trichoderma permeabilises Arabidopsis root apical meristem and epidermis but is antagonised by cellulase-induced resistance to alamethicin. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magelhaes, P.J.; Ram, S.J.; Abramoff, M.D. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, M.J.; Bibb, M.J.; Chandra, G.; Findlay, K.C.; Buttner, M.J. Genes required for aerial growth, cell division, and chromosome segregation are targets of WhiA before sporulation in Streptomyces venezuelae. MBio 2013, 4, e00684-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrudan, M.I.; Smakman, F.; Grimbergen, A.J.; Westhoff, S.; Miller, E.L.; van Wezel, G.P.; Rozen, D.E. Socially mediated induction and suppression of antibiosis during bacterial coexistence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11054–11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Drai, D.; Elmer, G.; Kafkafi, N.; Golani, I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav. Brain Res. 2001, 125, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováts, E. Gas-chromatographische charakterisierung organischer verbindungen. teil 1: Retentionsindices aliphatischer halogenide, alkohole, aldehyde und ketone. Helv. Chim. Acta 1958, 41, 1915–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamesch, P.; Berardini, T.Z.; Li, D.; Swarbreck, D.; Wilks, C.; Sasidharan, R.; Muller, R.; Dreher, K.; Alexander, D.L.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.; et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): Improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1202–D1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, S.; McCarthy, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Okoniewski, M.; Smyth, G.K.; Huber, W.; Robinson, M.D. Count-based differential expression analysis of rna sequencing data using r and bioconductor. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1765–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, E.; Leyns, L.; Vandesompele, J. Standardization of real-time pcr gene expression data from independent biological replicates. Anal. Biochem. 2008, 379, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koressaar, T.; Remm, M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program primer3. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1289–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okushima, Y.; Overvoorde, P.J.; Arima, K.; Alonso, J.M.; Chan, A.; Chang, C.; Ecker, J.R.; Hughes, B.; Lui, A.; Nguyen, D.; et al. Functional genomic analysis of the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR gene family members in Arabidopsis thaliana: Unique and overlapping functions of ARF7 and ARF19. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, K.; Yamashino, T.; Yokoyama, A.; Mizuno, T. Three type-B response regulators, ARR1, ARR10 and ARR12, play essential but redundant roles in cytokinin signal transduction throughout the life cycle of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, J.P.C.; Haberer, G.; Ferreira, F.J.; Deruère, J.; Mason, M.G.; Schaller, G.E.; Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R.; Kieber, J.J. Type-A Arabidopsis response regulators are partially redundant negative regulators of cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, F.B.; Wilson, A.K.; Estelle, M. The AUX1 mutation of Arabidopsis confers both auxin and ethylene resistance. Plant Physiol. 1990, 94, 1462–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, M.; Pischke, M.S.; Mähönen, A.P.; Miyawaki, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Seki, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Kato, T.; Tabata, S.; et al. In planta functions of the Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8821–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottenschläger, I.; Wolff, P.; Wolverton, C.; Bhalerao, R.P.; Sandberg, G.; Ishikawa, H.; Evans, M.; Palme, K. Gravity-regulated differential auxin transport from columella to lateral root cap cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2987–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, P.; Ecker, J.R. Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 1990, 2, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleecker, A.B.; Estelle, M.A.; Somerville, C.; Kende, H. Insensitivity to ethylene conferred by a dominant mutation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 1988, 241, 1086–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirnberg, P.; van de Sande, K.; Leyser, H.M.O. MAX1 and MAX2 control shoot lateral branching in Arabidopsis. Development 2002, 129, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegger, M.; Dewey, E.; Gray, W.M.; Hobbie, L.; Turner, J.; Estelle, M. The TIR1 protein of Arabidopsis functions in auxin response and is related to human SKP2 and yeast grr1p. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koornneef, M.; Reuling, G.; Karssen, C.M. The isolation and characterization of abscisic acid-insensitive mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol. Plant. 1984, 61, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koorneef, M.; Elgersma, A.; Hanhart, C.J.; Loenen-Martinet, E.P.; Rijn, L.; Zeevaart, J.A.D. A gibberellin insensitive mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol. Plant. 1985, 65, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, T.; Fujioka, S.; Choe, S.; Takatsuto, S.; Yoshida, S.; Yuan, H.; Feldmann, K.A.; Tax, F.E. Brassinosteroid-insensitive dwarf mutants of Arabidopsis accumulate brassinosteroids. Plant Physiol. 1999, 121, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becher, P.G.; Verschut, V.; Bibb, M.J.; Bush, M.J.; Molnár, B.P.; Barane, E.; Al-Bassam, M.M.; Chandra, G.; Song, L.; Challis, G.L.; et al. Developmentally regulated volatiles geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol attract a soil arthropod to Streptomyces bacteria promoting spore dispersal. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Chater, K.; Lee, K.; Hesketh, A. Changes in the extracellular proteome caused by the absence of the BldA gene product, a developmentally significant tRNA, reveal a new target for the pleiotropic regulator AdpA in Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 2957–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, M.J.; Chandra, G.; Al-Bassam, M.M.; Findlay, K.C.; Buttner, M.J. BldC delays entry into development to produce a sustained period of vegetative growth in Streptomyces venezuelae. MBio 2019, 10, e02812-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S.c. M145 | S.c. bldA | S.c. bldM | S.v. | K.I. Exp. | K.I. Pub. | CAS Number | ID Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-unknown | 0.03 ± 0.01 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 1134 | - | - | MS |

| B-unknown | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 6.8 ± 0.3 | 1147 | - | - | MS |

| 3-Octanone | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | N.D. | 1260 | 1266 | 106-68-3 | MS, KI, RC |

| Styrene | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1263 | 1259 | 100-42-5 | MS, KI |

| Chalcogran (i) | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | N.D. | 1357 | 1343 | 35401-84-2 | MS, KI, RC |

| Chalcogran (ii) | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | N.D. | 1361 | 1348 | 35401-84-2 | MS, KI, RC |

| C§-unknown | 0.36 ± 0.04 | N.D. | 1.3 ± 0.3 | N.D. | 1436 | - | - | - |

| 2-Methyl-Isoborneol | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | N.D. | 60.7 ± 4.6 | 1595 | 1602 | 2371-42-8 | MS, KI, RC |

| E-unknown | 0.33 ± 0.04 | N.D. | 2.7 ± 0.4 | N.D. | 1610 | - | - | MS |

| F-unknown | N.D. | 0.7 ± 0.4 | N.D. | 1.7 ± 1.6 | 1714 | - | - | MS |

| Germacrene D | 9.9 ± 1.9 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | N.D. | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1724 | 1724 | 483-76-1 | MS, KI |

| G-unknown | N.D. | 42.8 ± 3.1 | 30.8 ± 2.4 | N.D. | 1732 | - | - | MS |

| H-unknown | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1747 | - | - | MS |

| Geosmin | 49.1 ± 3.2 | 6.9 ± 0.2 | N.D. | 6.2 ± 2.0 | 1845 | 1858 | 19700-21-1 | MS, KI, RC |

| I-unknown | 1.7 ± 0.5 | N.D. | N.D. | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 2150 | - | - | MS |

| Species | Experiment Description | Experiment Number | Searched Dataset Collection | GEO Number | Similarity Score | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serratia plymuthica HRO-C | 48 volatile-treated seedlings/mock-treated seedling (24 h after treatment) | AT-00496 | ATH1 Microarray | GSE35325 | 2.6 | [31] |

| Colletotrichum tofieldiae | inoculated seedling roots (low P)/untreated seedling roots (sufficient P) (10 days after inoculation) | AT-00754 | RNASEQ | GSE70094 | 2.6 | [32] |

| Colletotrichum incanum | inoculated seedling roots (low P)/untreated seedling roots (sufficient P) (10 days after inoculation) | AT-00754 | RNASEQ | GSE70094 | 2.3 | [32] |

| (a) Program | Description of Bin | GO Bin Hits | GO Bin Size | GO Term | FDR q-Value |

| Genevestigator | Negative Regulation of Cytokinin-Activated Signaling Pathways | 3 | 3 | 80,037 | 0.008 |

| Genevestigator | Biological Process | 116 | 22,565 | 8150 | 0.008 |

| Genevestigator | Response to Stimulus | 52 | 6661 | 50,896 | 0.014 |

| Gorilla | Cell Wall Organization | 20 | 109 | 71,555 | 0.071 |

| Gorilla | Regulation of Phenylpropanoid Metabolic Process | 4 | 5 | 2,000,762 | 0.09 |

| (b) Gene Number | Gene Description | Average FPKM Control | Average FPKM S.c. Volatiles | Fold Change S.c. Volatiles/Control | GO Bin |

| At1g80440 | Galactose oxidase/kelch repeat superfamily protein; KISS ME DEADLY 1 | 95.8 | 182.5 | 1.9 | GO:80037; GO:0008150; GO:0050896; GO:2000762 |

| At1g15670 | Galactose oxidase/kelch repeat superfamily protein; KISS ME DEADLY 2 | 104.1 | 171.2 | 1.7 | GO:80037; GO:0008150; GO:0050896; GO:2000762 |

| At2g44130 | Galactose oxidase/kelch repeat superfamily protein; KISS ME DEADLY 3 | 67.7 | 113.2 | 1.7 | GO:0008150; GO:0050896; GO:2000762 |

| At3g59940 | Galactose oxidase/kelch repeat superfamily protein; KISS ME DEADLY 4 | 221.4 | 302.6 | 1.4 | GO:80037; GO:0008150; GO:0050896; GO:2000762 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dotson, B.R.; Verschut, V.; Flärdh, K.; Becher, P.G.; Rasmusson, A.G. Streptomyces Volatiles Alter Auxin/Cytokinin Signaling, Root Architecture, and Growth Rate in Arabidopsis thaliana via Signaling Through the KISS ME DEADLY Gene Family. Plants 2026, 15, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010124

Dotson BR, Verschut V, Flärdh K, Becher PG, Rasmusson AG. Streptomyces Volatiles Alter Auxin/Cytokinin Signaling, Root Architecture, and Growth Rate in Arabidopsis thaliana via Signaling Through the KISS ME DEADLY Gene Family. Plants. 2026; 15(1):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010124

Chicago/Turabian StyleDotson, Bradley R., Vasiliki Verschut, Klas Flärdh, Paul G. Becher, and Allan G. Rasmusson. 2026. "Streptomyces Volatiles Alter Auxin/Cytokinin Signaling, Root Architecture, and Growth Rate in Arabidopsis thaliana via Signaling Through the KISS ME DEADLY Gene Family" Plants 15, no. 1: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010124

APA StyleDotson, B. R., Verschut, V., Flärdh, K., Becher, P. G., & Rasmusson, A. G. (2026). Streptomyces Volatiles Alter Auxin/Cytokinin Signaling, Root Architecture, and Growth Rate in Arabidopsis thaliana via Signaling Through the KISS ME DEADLY Gene Family. Plants, 15(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010124