The Use of Rhizospheric Microorganisms of Crotalaria for the Determination of Toxicity and Phytoremediation to Certain Petroleum Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effect of CRO on Rhizobia and Nodules at Different Stages of the Crotalaria Life Cycle

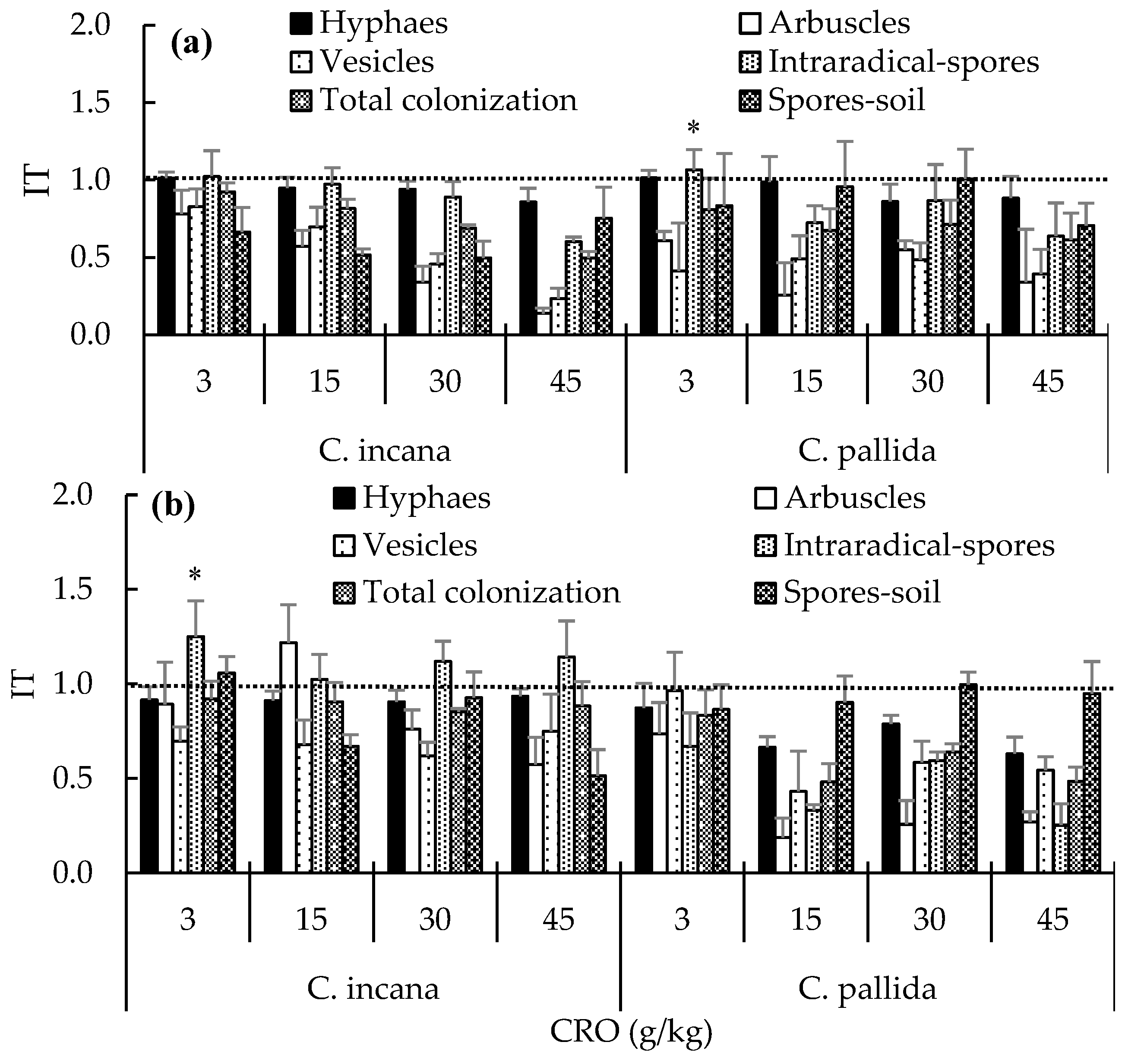

2.2. Effects of CRO on AMFs According to the Crotalaria Growth Stage

2.3. Effects of Petroleum Toxicity on Rhizobium, Nodule and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungy

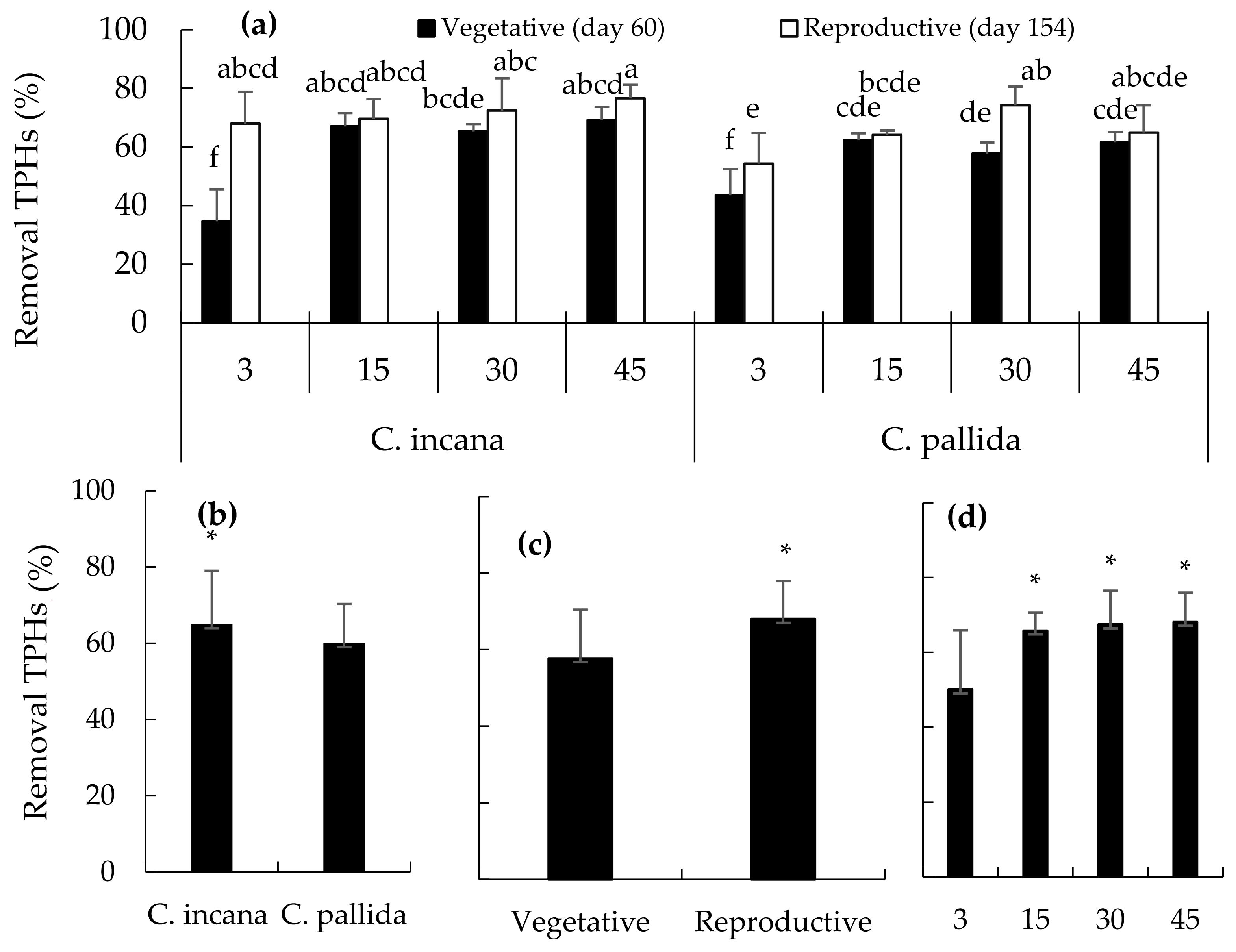

2.4. Removal of Total Hydrocarbons from Crude Oil

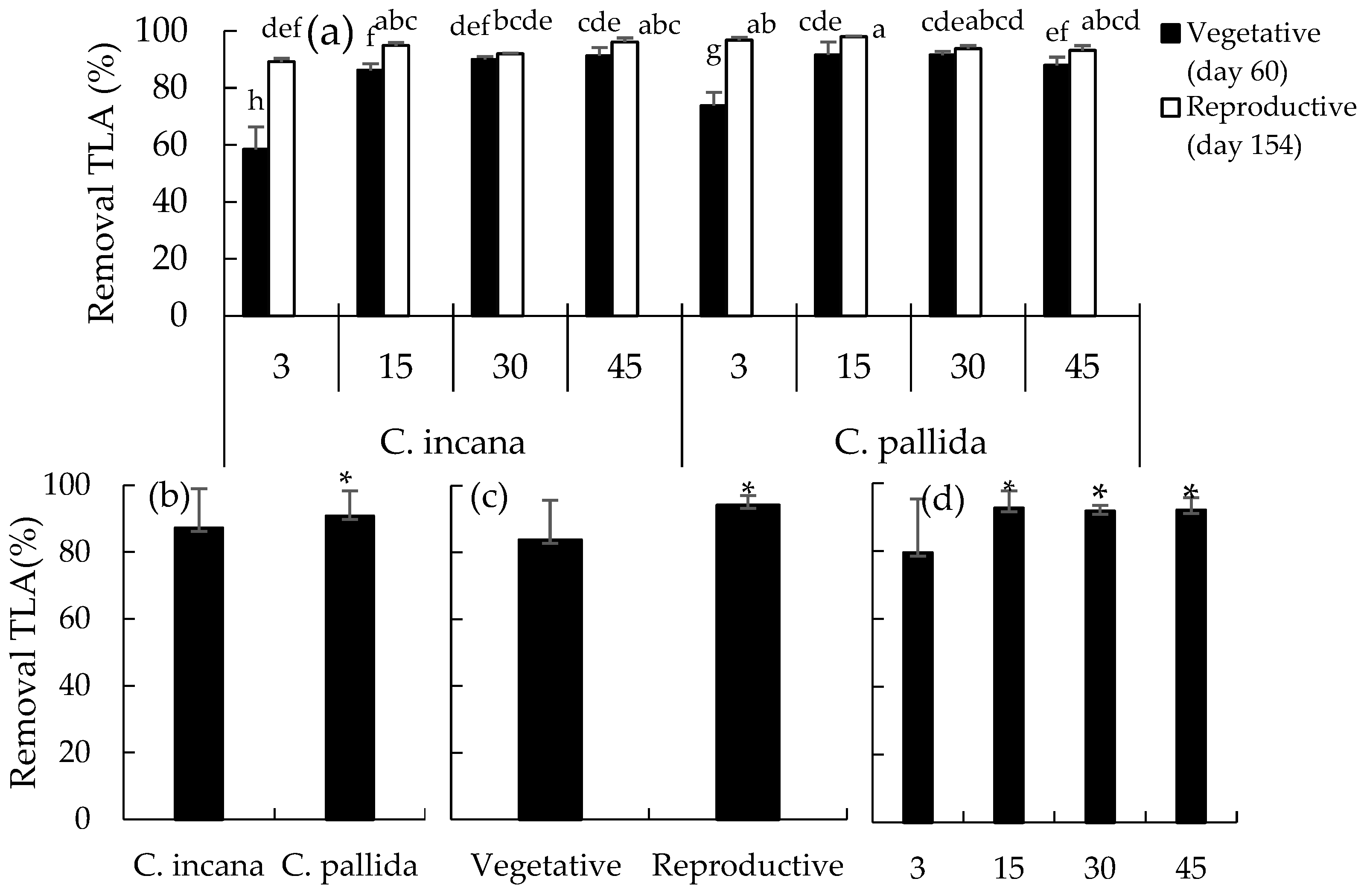

2.5. Removal of Linear Alkane from Crude Oil

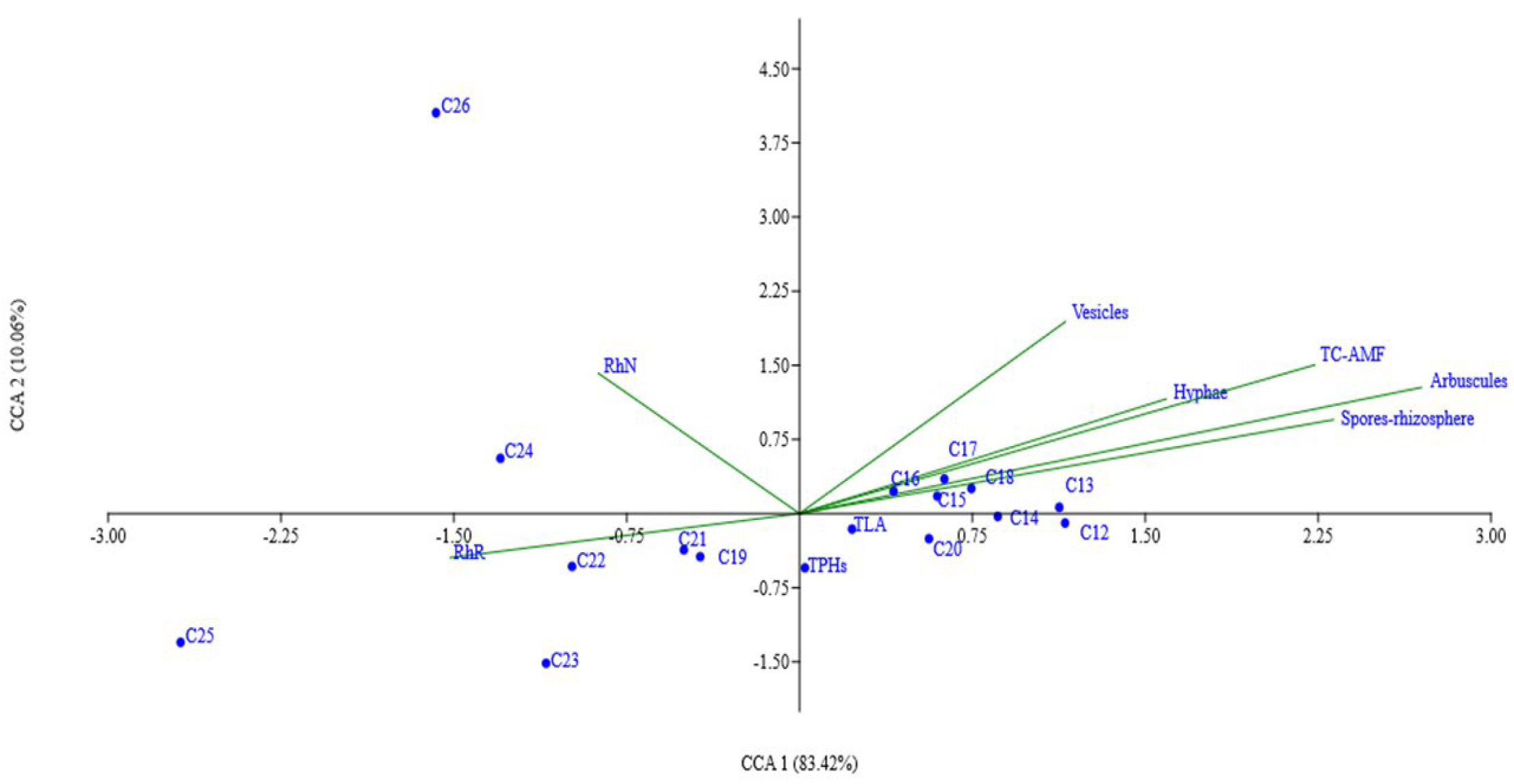

2.6. Linear Alkanes Removal and Microbiological Association

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

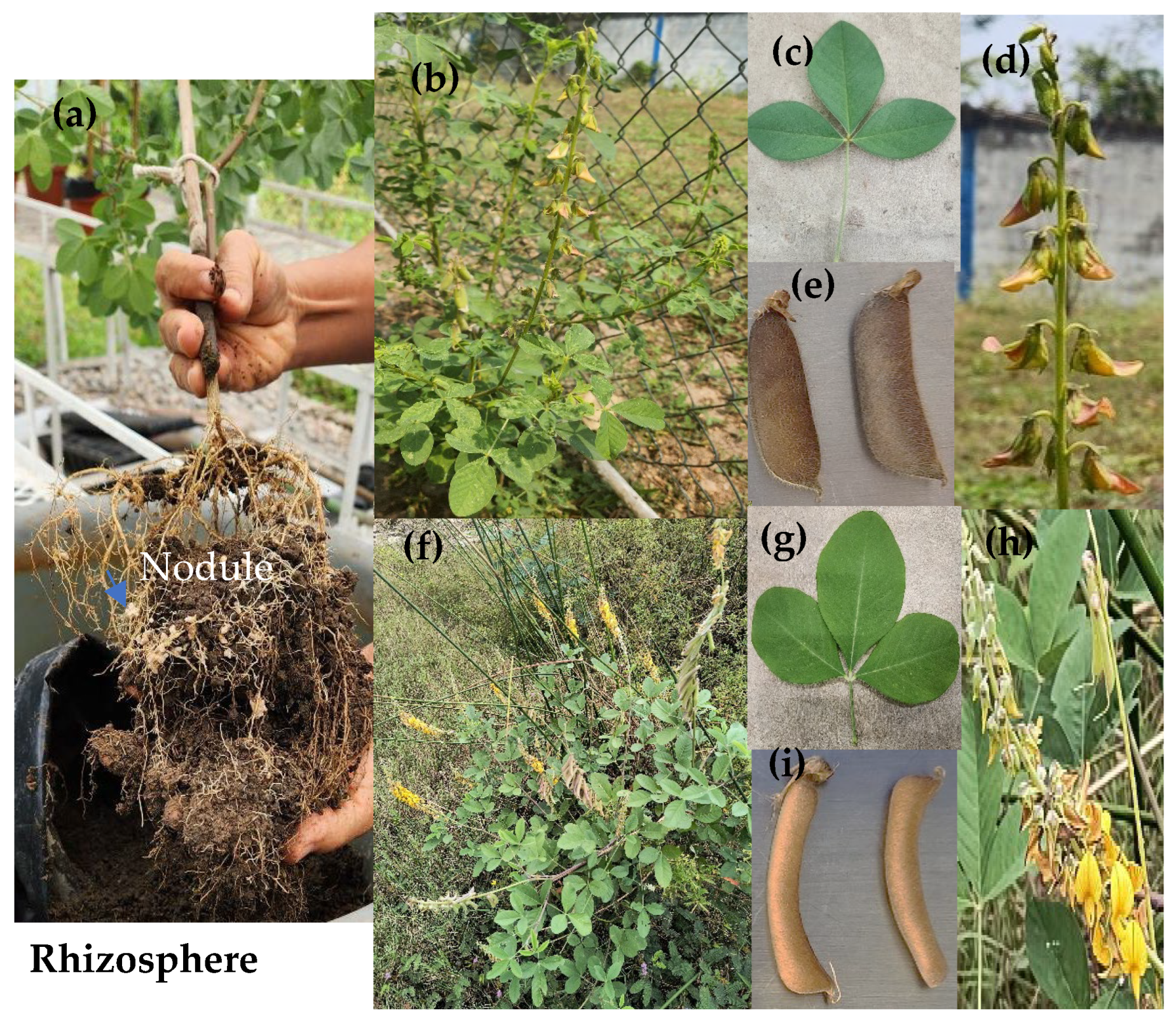

4.1. Soil, Plants, and Crude Oil

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Nodules and Population of Microorganisms

4.4. Index of Toxicity

4.5. Analysis of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons and Linear Alkanes

4.6. Removal of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons and Linear Alkanes

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMFs | Arbuscular mycorrizal fungi |

| CFUs | Colony-forming units |

| CRO | Crude oil |

| IT | Index of toxicity |

| LAs | Linear alkanes |

| NN | Number of nodules |

| RhN | Rhizobium in nodule |

| RhR | Rhizobia in rhizosphere |

| RS | Reproductive stage |

| TLA | Total linear alkanes |

| TPHs | Total petroleum hydrocarbons |

| VS | Vegetative stage |

References

- Huesemann, M.H. Guidelines for land-treating petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil. J. Soil. Contam. 1994, 3, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuji, C.; Onojake, C.M. Trace heavy metals associated with crude oil: A case study of ebocha-8 oil-spill-polluted site in Niger Delta, Nigeria. Chem. Biodivers. 2004, 1, 1708–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). Toxicological Profile for Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1999; p. 315.

- Le Roux, M.M.; Boatwright, J.S.; van Wyk, B.-E. A global infrageneric classification system for the genus Crotalaria (Leguminosae) based on molecular and morphological evidence. Taxon 2013, 62, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowsher, C.; Tobin, A. Plant Biochemistry, 2nd ed.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; p. 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yuan, J.; Gao, H. Microbial oxidative stress response: Novel insights from environmental facultative anaerobic bacteria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 584, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotmann, U.; Durand, M.J.; Thouand, G.; Eberlein, C.; Helpleper, J.H.; Gartiser, S.; Pagga, U. Microbiological toxicity tests using standardized ISO/OECD methods-current state and outlook. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro-Córdova, A.; Rivera-Cruz, M.C.; Hernández-Cuevas, L.V.; Alarcón, A.; Trujillo-Narcía, A.; García-de la Cruz, R. Responses of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and grass Leersia hexandra Swartz exposed to soil with crude oil. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2017, 228, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Álvarez, K.; Rivera-Cruz, M.d.C.; Aceves-Navarro, L.A.; Trujillo-Narcía, A.; García-de la Cruz, R.; Vega-López, A. Physiological and microbiological hormesis in sedge Eleocharis palustris induced by crude oil in phytoremediation of flooded clay soil. Ecotoxicology 2022, 31, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Blain, R.B. Hormesis and plant biology. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agathokleous, E.; Calabrese, E.J. Environmental toxicology and ecotoxicology: How clean is clean? Rethinking dose-response analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 138769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, P. Rhizosphere biology. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Plants, 4th ed.; Rengel, Z., Cakmak, I., White, P.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 587–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iffis, B.; St-Arnaud, M.; Hijri, M. Petroleum contamination and plant identity influence soil and root microbial communities while AMF spores retrieved from the same plants possess markedly different communities. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joner, E.J.; Leyval, C. Rhizosphere gradients of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) dissipation in two industrial soils and the impact of arbuscular mycorrhiza. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 2371–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, M.T.; Bender, K.S.; Buckley, D.H.; Sattley, W.M.; Stahl, D.A. Brock Biología de los Microorganismos, 16th ed.; Pearson Educación: London, UK, 2022; p. 1124. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasian, F.; Lockington, R.; Mallavarapu, M.; Naidu, R. A comprehensive review of aliphatic hydrocarbon biodegradation by bacteria. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 176, 670–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.; Gu, L.; Guo, C.; Xun, F.; Liu, J. Effect of PGPR Serratia marcescens BC-3 and AMF Glomus intraradices on phytoremediation of petroleum contaminated soil. Ecotoxicology 2014, 23, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourbabaee, A.A.; Khazaei, M.; Alikhani, H.A.; Emami, S. Root nodulation of alfalfa by Ensifer meliloti in petroleum contaminated soil. Rhizosphere 2021, 17, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, N.; Khanafer, M.; El-Nemr, I.; Sorkhoh, N.; Ali, N.; Radwan, S. The potential of oil-utilizing bacterial consortia associated with legume root nodules for cleaning oily soils. Chemosphere 2009, 74, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, L.P.; Pandey, P. Rhizosphere assisted bioengineering approaches for the mitigation of petroleum hydrocarbons contamination in soil. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, G.; Lal, M.A. Physiology of flowering. In Plant Physiology, Development and Metabolism; Bhatla, S.C., Lal, M.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2018; pp. 797–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.J.; Ding, G. Long-distance transport in the xylem and phloem. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Plants, 4th ed.; Rengel, Z., Cakmak, I., White, P.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, G.; Ludewing, U. Rhizosphere chemistry influencing plant nutrition. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Plants, 4th ed.; Rengel, Z., Cakmak, I., White, P.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 545–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J.J.; Maranho, L.T. Rhizospheric microorganisms as a solution for the recovery of soils contaminated by petroleum: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 210, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambaye, T.G.; Chebbi, A.; Formicola, F.; Prasad, S.; Gomez, F.H.; Franzetti, A.; Vaccari, M. Remediation of soil polluted with petroleum hydrocarbons and its reuse for agriculture: Recent progress, challenges, and perspectives. Chemosphere 2022, 293, 133572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riskuwa-Shehu, M.L.; Ijah, U.J.J.; Manga, S.B.; Bilbis, L.S. Evaluation of the use of legumes for biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons in soil. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 14, 2205–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubogu, M.; Akponah, E.; Ejukonemu, E.F. Response of Rhizobium to spent engine-oil contamination in the rhizosphere of legumes (Arachis hypogaea and Phaseolus vulgaris). Kuwait J. Sci. 2019, 46, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Luna, D.; Castelán-Estrada, M.; Rivera-Cruz, M.d.C.; Ortíz-Ceballos, A.I.; Izquierdo, R.F. Crotalaria incana L. y Leucaena leucocephala Lam. (Leguminosae): Especies indicadoras de toxicidad por hidrocarburos de petróleo en el suelo. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambie. 2010, 26, 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, H.; Smith, K.E.C.; Wick, L.Y. Problems of hydrophobicity/bioavailability: An introduction. In Cellular Ecophysiology of Microbe: Hydrocarbon and Lipid Interactions; Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology; Krell, T., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarighat, H.; Boustani, P.; Farahbod, F. Laboratory investigation of removal of total petroleum hydrocarbons from oil-contaminated soil using Santolina plant. Egyp. J. Pet. 2024, 33, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Yang, J.; Yu, N.; Wang, E. Hormone modulation of legume-rhizobial symbiosis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, D.J.; Krieg, N.R.; Staley, J.T.; Garrity, G.M. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd ed.; (The Proteobacteria), part C (The Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, and Epsilonproteobacteria); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 2, p. 1388. [Google Scholar]

- Chaulagain, D.; Frugoli, J. The regulation of nodule number in legumes is a balance of three signal transduction pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, U.; Khan, A.H.A.; Farooqi, A.; Muhammad, Y.S.; Barros, R.; Tamayo-Ramos, J.A.; Iqbal, M.; Yousaf, S. Interactive effect of biochar and compost with Poaceae and Fabaceae plants on remediation of total petroleum hydrocarbons in crude oil contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thies, J.E. Biological dinitrogen fixation: Symbiotic. In Principles and Applications of Soil Microbiology, 3rd ed.; Gentry, T.J., Fuhrmann, J.J., Zuberer, D.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 455–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osadebe, A.U.; Chukwu, C.B. Degradation properties of Rhizobium petrolearium on different concentrations of crude oil and its derivative fuels. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 21, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.M.C.; Winter, H.; Storer, P.J.; Bussell, J.D.; Schuller, K.A.; Atkins, C.A. Effect of short-term N2 deficiency on expression of the ureide pathway in cowpea root nodules. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 1216–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiares, J.D.; Kenworthy, K.E.; Rhykerd, R.L. Root and shoot biomass of plants seeded in crude oil contaminated soil. TXJANR 2001, 14, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers, H.; Oliveira, R.S. Plant Physiological Ecology, 3rd ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; p. 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Canigia, M.V. Factores Determinantes de la Nodulación: Edición Ampliada y Actualizada, 1st ed.; Grasso, A., Ed.; Libro Digital: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2020; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers, H.; Poorter, H. Inherent variation in growth rate between higher plants: A search for physiological causes and ecological consequences. In Advances in Ecological Research: Classic Papers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 23, pp. 187–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcon-Bieto, J.; Talón, M. Fundamentos de Fisiología Vegetal, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España: Madrid, Spain; Publicacions I Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2013; p. 651. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Trinidad, A.; Rivera-Cruz, M.C.; Trujillo-Narcía, A. Fitotoxicidad de un suelo contaminado con petróleo fresco sobre Phaseolus vulgaris L. (Leguminosae). Rev. Int. Contam. Ambie. 2017, 33, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, A.; García-Díaz, M.; Hernández-Cuevas, L.V.; Esquivel-Cote, R.; Ferrera-Cerrato, R.; Almaraz-Suárez, J.J.; Ferrera-Rodríguez, O. Impact of crude oil on functional groups of culturable bacteria and colonization of symbiotic microorganisms in the Clitoria-Brachiaria rhizosphere grown in mesocosms. Acta Biol. Colomb. 2019, 24, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpo, M.A.; Nkanang, A.J. Nitrogen fixing capacity of legumes and their Rhizospheral microflora in diesel oil polluted soil in the tropics. J. Petroleum Gas. Eng. 2010, 1, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Akaninwor, J.O.; Ayeleso, A.O.; Monago, C.C. Effect of different concentrations of crude oil (Bonny light) on major food reserves in guinea corn during germination and growth. Sci. Res. Essay 2007, 2, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira do Nascimento, T.C.; Santos Oliveira, F.J.; Pessoa de França, F. Biorremediación de un suelo tropical contaminado con residuos aceitosos intemperizados. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2013, 29, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Redden, B.; Leonforte, T.; Ford, R.; Croser, J.; Slattery, J. Pea (Pisum sativum L.). In Genetic Resources, Chromosome Engineering, and Crop Improvement; Singh, R.J., Jauhar, P.P., Eds.; Grain legumes; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 58–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, P.; Anjum, N.A.; Muthukumar, T.; Sridevi, G.; Vasudhevan, P.; Maruthupandian, A. Arbuscular mycorrhizae: Natural modulators of plant-nutrient relation and growth in stressful environments. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M. Mycorrhizal Planet: How Symbiotic Fungi Work with Roots to Support Plant Health and Build Soil Fertility; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2017; p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Burak, K.; Yanardağ, H.I.; Gómez-López, M.D.; Faz, A.; Yalçin, H.; Sakin, E.; Ramazanoğlu, E.; Orak, A.B.; Yanardağ, A. The effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on biological activity and biochemical properties of soil under vetch growing conditions in calcareous soils. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Klironomos, J.N.; Ursic, M.; Moutoglis, P.; Streitwolf-Engel, R.; Boller, T.; Wiemken, A.; Sanders, I.R. Mycorrhizal fungal diversity determines plant biodiversity, ecosystem variability and productivity. Nature 1998, 396, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangaro, W.; Rostirola, L.V.; de Souza, P.B.; Alves, R.d.A.; Lescano, L.E.A.M.; Rondina, A.B.L.; Nogueira, M.A.; Carrenho, R. Root colonization and spore abundance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in distinct successional stages from an Atlantic rainforest biome in southern Brazil. Mycorrhiza 2013, 23, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajtor, M.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Prospects for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) to assist in phytoremediation of soil hydrocarbon contaminants. Chemosphere 2016, 162, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Ling, W.; Zhu, X. Arbuscular mycorrhizal phytoremediation of soils contaminated with phenanthrene and pyrene. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debiane, D.; Calonne, M.; Fontaine, J.; Laruelle, F.; Grandmoungin-Ferjani, A.; Lounes-Hadj Sahraoui, A. Lipid content disturbance in the arbuscular mycorrhizal, Glomus irregulare grown in monoxenic conditions under PAHs pollution. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.R.; Brady, C.N. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2017; p. 1104. [Google Scholar]

- Strotmann, U.; Pastor Flores, D.; Konrad, O.; Gendig, C. Bacterial Toxicity Testing: Modification and Evaluation of the Luminescent Bacteria Test and the Respiration Inhibition Test. Processes 2020, 8, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, D.J.; de la Providencia, I.E.; Pitre, F.E.; St-Arnaud, M.; Hijri, M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal assemblages significantly shifted upon bacterial inoculation in non-contaminated and petroleum-contaminated environments. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meištininkas, R.; Vaškevičiene, I.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.I.; Krupka, M.; Žaltauskaitė, J. Sustainable recovery of the health of soil with old petroleum hydrocarbon contamination through individual and microorganism-assisted phytoremediation with Lotus corniculatus. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Chávez, E.; Rivera-Cruz, M.C.; Izquierdo-Reyes, F.; Palma-López, D.J. Efectos de rizosfera, microorganismos y fertilización en la biorremediación y fitorremediación de suelos con petróleos crudo nuevo e intemperizado. Univ. Cienc. Trópico Húmedo 2010, 26, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Moubasher, H.A.; Hegazy, A.K.; Mohamed, N.H.; Moustafa, Y.M.; Kabiel, H.F.; Hamad, A.A. Phytoremediation of soils polluted with crude petroleum oil using Bassia scoparia and its associated rhizosphere microorganisms. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2015, 98, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, D.; Dussan, J. Landfarmed oil sludge as a carbon source for Canavalia ensiformis during phytoremediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 11, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.F.; Adnan, H.Z. Rule of Rhizobia and Bacillus in phytoremediation of contaminated soil with diesel oil. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2024, 23, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Bano, A.; Sattar, S.; Hashmi, M.Z.; Qin, M.; Shakoor, A. Hydrocarbon degradation in oily sludge by bacterial consortium assisted with alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) and maize (Zea mays L.). Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Wu, Y.; Fan, Q.; Li, P.; Liang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, R.; Li, R.; Shi, L. Remediating petroleum hydrocarbons in highly saline-alkali soils using three native plant species. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 339, 117928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Zhao, Z.; Bartlam, M.; Wang, Y. Combination of biochar amendment and phytoremediation for hydrocarbon removal in petroleum-contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 21219–21228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allamin, I.A.; Yasid, N.A.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Halmi, M.I.E.; Shukor, M.Y. Phyto-tolerance degradation of hydrocarbons and accumulation of heavy metals by of Cajanus cajan (Pigeon Pea) in petroleum-oily-sludge-contaminated Soil. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil by petroleum-degrading bacteria immobilized on biochar. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 35304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, F.; Shi, Q.; Luo, S.; Liu, C. Fast biodegradation of long-chain alkanes in heavily polluted soil by improving C/H conversion after pre-oxidation. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 186, 108594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steliga, T.; Kluk, D. Assessment of the suitability of Melilotus officinalis for phytoremediation of soil contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH and PAH), Zn, Pb and Cd based on toxicological tests. Toxics 2021, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, F. Degradation of alkanes by bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 2477–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, P.; Rehman, M.B. Biodegradation of diesel hydrocarbon in soil by bioaugmentation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A laboratory scale study. Int. J. Environ. Bioremediat. Biodegrad. 2014, 2, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.T.; Li, M.S.M.; McDowell, T.; MacDonald, J.; Yuan, Z.-C. Characterization and genomic analysis of a diesel-degrading bacterium, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus CA16, isolated from Canadian soil. BMC Biotechnol. 2020, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medić, A.; Lješević, M.; Inui, H.; Beškoski, V.; Kojić, I.; Stojanović, K.; Karadžić, I. Efficient biodegradation of petroleum n-alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by polyextremophilic Pseudomonas aeruginosa san ai with multidegradative capacity. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 14060–14070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, P.A.; La Montagne, M.G.; Bruce, A.K.; Miller, W.G.; Lindow, S.E. Assessing the role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface-active gene expression in hexadecane biodegradation in sand. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afkhami, M.E.; Stinchcombe, J.R. Multiple mutualist effects on genomewide expression in the tripartite association between Medicago truncatula, nitrogen-fixing bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 4946–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Dong, W.; Murray, J.; Wang, E. Innovation and appropriation in mycorrhizal and rhizobial symbioses. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 1573–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.B.; Hayman, D.S. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 1970, 55, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdemann, J.W.; Nicolson, T.H. Spores of mycorrhizal endogone species extracted from soil by wet sieving and decanting. Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 1963, 46, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, B.A.; Skipper, H.D. Methods for the recovery and quantitative estimation of propagules from soil. In Methods and Principles of Mycorrhizal Research; Schenck, N.C., Ed.; American Phytopathological Society: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 1982; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA-3540C. Soxhlet Extraction Organics. SW-846 Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste Physical/Chemical Methods. 1996. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/hw-sw846/sw-846-test-method-3540c-soxhlet-extraction (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Cam, D.; Gagni, S. Determination of petroleum hydrocarbons in contaminated soils using solid-phase microextraction with Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2001, 39, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| T | Crotalaria/Stage | CRO (g/kg) | (104 CFUs g−1) | NN | IT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RhR | RhN | RhR | RhN | NN | ||||

| 1 | incana/VS | 0 | 13 i | 8 g | 182 efg | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 2 | 3 | 18 i | 1 g | 203 efg | 1.4 | 0.1 | 1.1 | |

| 3 | 15 | 144 fgh | 11 g | 184 efg | 11.1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | |

| 4 | 30 | 144 fgh | 3 g | 78 h | 11.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| 5 | 45 | 150 fgh | 3 g | 54 hi | 11.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| 6 | pallida/VS | 0 | 8 i | 3 g | 166 g | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 7 | 3 | 79 hi | 3 g | 162 g | 9.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 8 | 15 | 89 ghi | 6 g | 63 hi | 11.1 | 2.0 | 0.4 | |

| 9 | 30 | 11 i | 22 g | 28 hi | 1.4 | 7.3 | 0.2 | |

| 10 | 45 | 74 hi | 26 g | 11 i | 9.2 | 8.7 | 0.1 | |

| 11 | incana/RS | 0 | 282 e | 916 a | 515 c | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 12 | 3 | 218 ef | 620 b | 369 d | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| 13 | 15 | 1034 c | 439 d | 375 d | 3.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | |

| 14 | 30 | 1110 c | 275 e | 585 b | 3.9 | 0.3 | 1.1 | |

| 15 | 45 | 1301 b | 277 e | 657 a | 4.6 | 0.3 | 1.3 | |

| 16 | pallida/RS | 0 | 218 ef | 580 c | 470 c | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 17 | 3 | 138 fgh | 219 f | 243 e | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| 18 | 15 | 196 efg | 33 g | 189 efg | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.4 | |

| 19 | 30 | 773 d | 26 g | 172 fg | 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.4 | |

| 20 | 45 | 1792 a | 17 g | 233 ef | 8.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| Factor | ||||||||

| Crotalaria | incana | 441 * | 255 * | 320 * | 6.0 | 0.5 | 0.8 | |

| pallida | 338 * | 93 | 173 | 5.6 | 2.4 | 0.4 | ||

| Stage | VS | 73 | 9 | 113 | 8.3 | 2.7 | 0.6 | |

| RS | 706 * | 340 * | 381 * | 3.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | ||

| CRO | Without | 130 * | 377 * | 333 * | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| With | 454 | 124 | 225 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 0.67 | ||

| T | Crotalaria/Stage | CRO (g/kg) | Colonization (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyphae | Arbuscules | Vesicles | Intraradical-Spores | Spores-Rhizosphere | |||

| 1 | incana/VS | 0 | 95 * | 63 * | 77 * | 80 * | 1905 * |

| 2 | 3 | 96 * | 50 | 63 | 82 * | 1266 | |

| 3 | 15 | 90 * | 36 | 53 | 78 * | 984 | |

| 4 | 30 | 90 * | 22 | 35 | 71 | 947 | |

| 5 | 45 | 82 | 9 | 18 | 48 | 1436 | |

| 6 | pallida/VS | 0 | 76 | 40 | 48 | 44 | 1169 |

| 7 | 3 | 77 | 25 | 20 | 47 | 975 | |

| 8 | 15 | 75 | 10 | 24 | 32 | 1119 | |

| 9 | 30 | 65 | 22 | 23 | 38 | 1177 | |

| 10 | 45 | 67 | 9 | 19 | 28 | 826 | |

| 11 | incana/RS | 0 | 96 * | 29 | 70 * | 52 | 1463 |

| 12 | 3 | 88 | 26 | 49 | 65 | 1548 | |

| 13 | 15 | 88 | 35 | 47 | 53 | 981 | |

| 14 | 30 | 87 | 22 | 43 | 58 | 1357 | |

| 15 | 45 | 90 | 17 | 53 | 59 | 753 | |

| 16 | pallida/RS | 0 | 96 * | 22 | 58 | 54 | 1264 |

| 17 | 3 | 84 | 16 | 56 | 36 | 1094 | |

| 18 | 15 | 64 | 4 | 25 | 18 | 1141 | |

| 19 | 30 | 75 | 6 | 34 | 32 | 1260 | |

| 20 | 45 | 60 | 6 | 31 | 14 | 1199 | |

| Crotalaria | |||||||

| incana | 90 a | 31 a | 51 a | 64 a | 1264 a | ||

| pallida | 74 b | 17 b | 34 b | 34 b | 1122 b | ||

| Stage | |||||||

| Vegetative | 81 a | 29 a | 38 b | 55 a | 1180 a | ||

| Reproductive | 83 b | 18 b | 47 a | 44 b | 1206 a | ||

| CRO | |||||||

| Without | 91 a | 39 a | 63 a | 57 a | 1450 a | ||

| With | 80 b | 20 b | 37 b | 47 b | 1129 b | ||

| Crotalaria/Stage | CRO g/kg | Linear Alkane (Carbon Chain Length) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | ||

| ------------------------------------------------------------Removal (%)----------------------------------------------------- | ||||||||||||||||

| incana | 3 | 100 * | 100 * | 85 | 75 | 68 | 74 | 79 | 30 | 69 | 30 | 17 | 5 | 21 | 22 | 29 |

| (VS) | 15 | 98 | 96 | 93 | 90 | 86 | 88 | 89 | 85 * | 85 | 81 | 71 | 65 | 55 | 43 | 34 |

| 30 | 98 | 97 | 95 | 94 | 92 | 87 | 89 | 91 * | 90 | 83 | 78 | 72 | 67 | 53 | 57 | |

| 45 | 97 | 94 | 93 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 92 * | 92 | 89 * | 87 * | 84 | 78 | 71 | 61 | |

| pallida | 3 | 100 * | 100 * | 100 * | 86 | 79 | 83 | 85 | 57 | 78 | 58 | 50 | 90 * | 45 | 25 | 29 |

| (VS) | 15 | 99 | 97 | 97 | 95 | 93 | 92 | 92 | 90 * | 88 | 87 * | 83 | 75 | 74 | 74 | 70 |

| 30 | 98 | 96 | 95 | 94 | 93 | 90 | 92 | 94 * | 91 | 84 * | 85 * | 79 | 75 | 65 | 45 | |

| 45 | 95 | 91 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 90 | 89 | 89 * | 88 | 86 * | 83 | 79 | 73 | 66 | 51 | |

| incana | 3 | 100 * | 100 * | 100 * | 97 | 96 | 94 | 94 | 86 * | 84 | 82 | 78 | 69 | 81 | 47 | 87 |

| (RS) | 15 | 100 * | 100 * | 99 * | 99 * | 96 | 95 * | 94 | 96 * | 94 * | 92 * | 82 | 78 | 86 | 82 | 72 |

| 30 | 100 * | 100 * | 98 * | 95 | 92 | 90 | 93 | 91 * | 90 | 86 * | 79 | 77 | 71 | 55 | 58 | |

| 45 | 100 * | 100 * | 98 * | 98 * | 98 * | 95 * | 95 | 94 * | 95 * | 93 * | 93 * | 91 * | 90 * | 89 | 7 | |

| pallida | 3 | 100 * | 100 * | 100 * | 100 * | 100 * | 99 * | 99 * | 95 * | 97 * | 92 * | 92 * | 100 * | 90 * | 70 | 95 * |

| (RS) | 15 | 100 * | 100 * | 100 * | 100 * | 99 * | 98 * | 97 * | 98 * | 96 * | 97 * | 92 * | 94 * | 91 * | 93 * | 93 * |

| 30 | 100 * | 100 * | 98 * | 96 | 94 | 91 | 95 | 94 * | 92 | 89 * | 87 * | 79 | 83 | 76 | 54 | |

| 45 | 100 * | 100 * | 98 * | 95 | 94 | 90 | 89 | 91 * | 90 | 88 * | 93 * | 92 * | 92 * | 90 * | 73 | |

| Crotalaria | ||||||||||||||||

| incana | 99 a | 98 a | 95 b | 92 b | 90 b | 90 b | 91 b | 83 b | 87 a | 80 b | 73 b | 68 b | 69 b | 67 b | 60 a | |

| pallida | 99 a | 98 a | 97 a | 94 a | 92 a | 92 a | 92 a | 88 a | 90 a | 85 a | 83 a | 86 a | 78 a | 70 a | 64 a | |

| Stage | ||||||||||||||||

| VS | 98 b | 96 b | 94 b | 89 b | 86 b | 87 b | 88 b | 78 b | 85 b | 80 b | 69 b | 69 b | 61 b | 52 b | 47 b | |

| RS | 100 a | 100 a | 99 a | 97 a | 96 a | 94 a | 94 a | 93 a | 92 a | 90 a | 87 a | 85 a | 85 a | 75 a | 76 a | |

| CRO (g/kg dw) | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 100 a | 100 a | 96 a | 90 c | 86 b | 88 b | 89 c | 67 b | 82 b | 66 b | 59 c | 66 c | 59 c | 41 c | 60 ab | |

| 15 | 99 b | 98 b | 97 a | 96 a | 94 a | 94 a | 93 a | 92 a | 91 a | 89 a | 82 b | 78 b | 76 b | 73 a | 67 a | |

| 30 | 99 b | 98 b | 97 a | 95 ab | 93 a | 89 b | 92 ab | 92 a | 91 a | 86 a | 82 b | 77 b | 74 b | 62 b | 54 b | |

| 45 | 98 c | 96 c | 95 b | 93 b | 93 a | 92 a | 91 b | 91 a | 91 a | 89 a | 89 a | 86 a | 83 a | 79 a | 66 a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ramírez-May, A.G.; Rivera-Cruz, M.d.C.; Mendoza-López, M.R.; Acosta-Pech, R.G.; Trujillo-Narcía, A.; Bautista-Muñoz, C. The Use of Rhizospheric Microorganisms of Crotalaria for the Determination of Toxicity and Phytoremediation to Certain Petroleum Compounds. Plants 2026, 15, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010103

Ramírez-May AG, Rivera-Cruz MdC, Mendoza-López MR, Acosta-Pech RG, Trujillo-Narcía A, Bautista-Muñoz C. The Use of Rhizospheric Microorganisms of Crotalaria for the Determination of Toxicity and Phytoremediation to Certain Petroleum Compounds. Plants. 2026; 15(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010103

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamírez-May, Ana Guadalupe, María del Carmen Rivera-Cruz, María Remedios Mendoza-López, Rocío Guadalupe Acosta-Pech, Antonio Trujillo-Narcía, and Consuelo Bautista-Muñoz. 2026. "The Use of Rhizospheric Microorganisms of Crotalaria for the Determination of Toxicity and Phytoremediation to Certain Petroleum Compounds" Plants 15, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010103

APA StyleRamírez-May, A. G., Rivera-Cruz, M. d. C., Mendoza-López, M. R., Acosta-Pech, R. G., Trujillo-Narcía, A., & Bautista-Muñoz, C. (2026). The Use of Rhizospheric Microorganisms of Crotalaria for the Determination of Toxicity and Phytoremediation to Certain Petroleum Compounds. Plants, 15(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010103