Tortula murciana (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta), a New Species from Mediterranean Mountains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Taxonomy

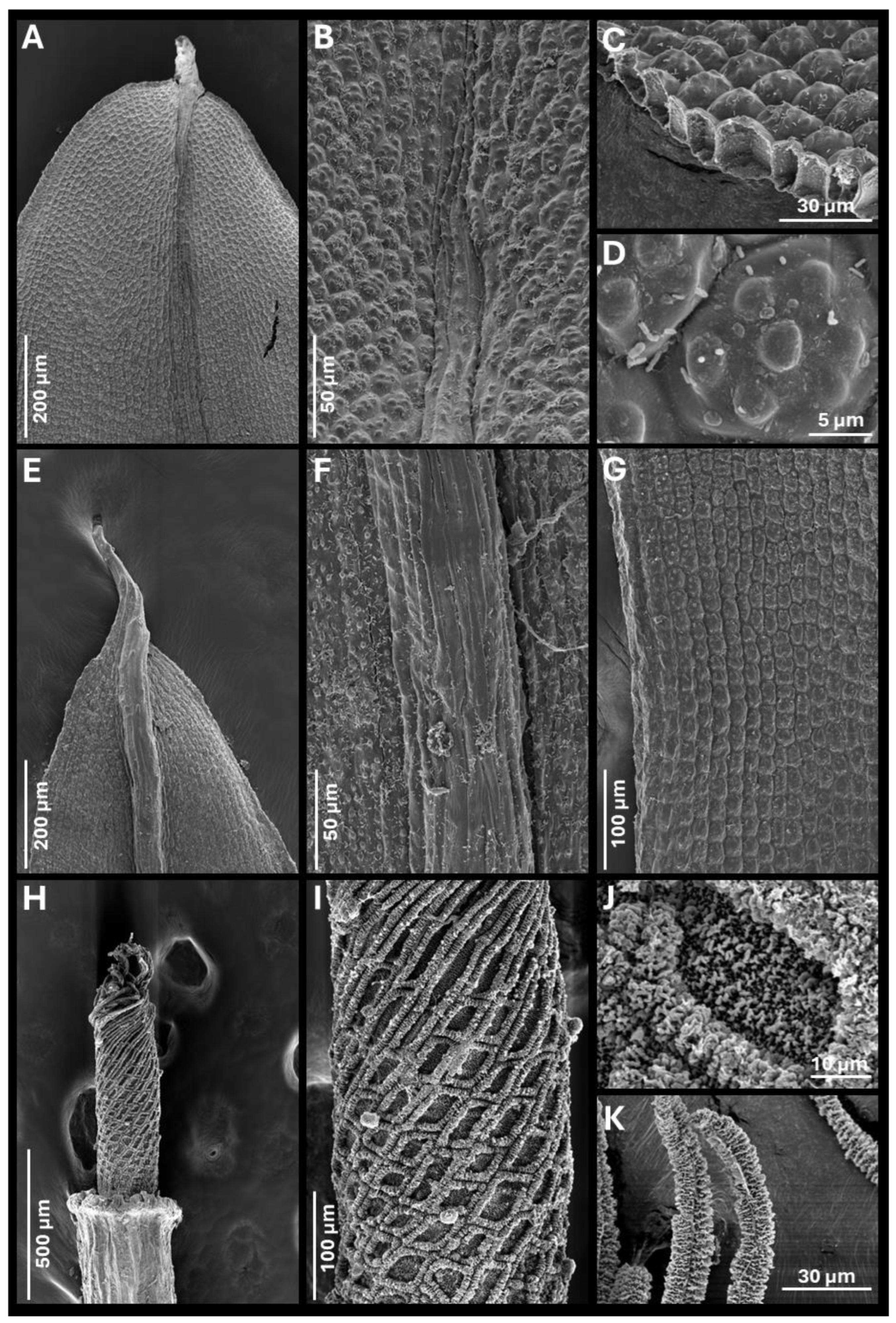

- Diagnosis. It can be distinguished from other closely related species of Tortula subulata complex by the following a unique combination of morphological traits: a translucent leaf lamina, upper laminal cells with 3–7 simple, wart-like papillae (verrucae), 2–3 µm high, middle laminal cells 16–24(35) µm wide, higher near the costa than towards the margins, and ventral epidermal cells of the costa at mid-leaf (when viewed in cross-section) that are quadrate to spherical, inflated, measuring 19.0–24.0 × 14.5–16.0 µm. The costa is robust, up to 140 µm wide at mid-leaf, papillose on the dorsal side, and excurrent in an apiculus, with the apical cell typically hyaline and often deciduous. Leaf border of differentiated cells is usually absent, more rarely poorly developed, non-yellowish, extending up to halfway of the leaf, with 2–3 rows of elongated, smooth cells. Basal membrane of the peristome 0.70–0.90 mm long, with a reticulate pattern where the lumina are delimited by strongly developed muri ornamented with globose, densely arranged clusters of ear-like lobes (auricles).

- Type. SPAIN: Murcia province, Revolcadores massif, ascent to Pico de los Obispos, 38.071260 N, 2.268584 W, 1814 m, alkaline, organic-rich soil accumulated between the roots of Pinus nigra, 1 August 2023, R.M. Ros & O. Werner s.n. (sample ID number 442), (holotype MUB 63607).

- Description. Plants 0.3–0.5 cm tall, yellowish green, growing in lax turfs; stems tomentose, branched; rhizoids orange, smooth, without gemmae; flagelliform shoots not observed; stem cross-section rounded, 350–410 µm wide, hyalodermis absent, scleroderm irregularly present, central strand present, sometimes poorly developed, 40–200 µm wide; axillary hairs hyaline, up to eight cells long, basal cell shorter and sometimes brown; median leaves usually individually spirally twisted, rarely twisted around the stem when dry, erect when moist, usually elliptical, rarely lanceolate, lingulate or spatulate, frequently concave, 3.3–4.5 × 0.7–1.6 mm, (2.3)2.6–4.5(5.9) times as long as wide; apex acute, short acuminate, or obtuse, more rarely rounded, not cucullate; margins recurved from base to 2/3 of leaf length, crenulate to papillose-crenulate, unistratose; leaf border of differentiated cells usually absent, more rarely poorly developed, non-yellowish, extending up to halfway of the leaf, with 2–3 rows of narrowed, smooth cells; costa greenish, gradually narrowing from base to apex, (55)80–140 µm wide at mid-leaf, excurrent in an apiculus (60)200–400(550) µm long, brownish, smooth, with a usually hyaline and deciduous apical cell 50–100 µm long; ventral epidermal cells of the costa at the upper part of the leaf elongated in the 1/4–1/5 upper part of the leaf (laminal cells not covering the costa, exposing ventral stereids), further down quadrate to rectangular, 4–5 cells across the weakly convex ventral surface, inflated and papillose; dorsal epidermal cells of the costa at mid-leaf elongate, slightly to strongly papillose; costa cross-section at mid-leaf circular to semicircular, with two guide cells in one layer, although sometimes appearing as four guide cells due to each of the two laminal cells on either side of the costa breaks through the costa, band of ventral stereids usually undifferentiated but sometimes present formed by 2 stereid layers, band of dorsal stereids semicircular, with (3)4–5 stereid layers, hydroids differentiated, ventral epidermal cells disposed mostly in one layer, sometimes in two layers, the external usually quadrate to spherical, inflated, 19.0–24.0 × 14.5–16.0 µm, dorsal epidermal cells differentiated; basal costa cross-section biconvex; upper lamina translucent, collenchymatous, trigones scarcely to strongly developed; upper laminal cells usually polygonal, sometimes quadrate, short-rectangular or oblate, (13)16–25(30) × (14)16–28(32) µm, usually thin-walled, sometimes thick-walled, walls 1.2(3.2) µm thick, bearing 3–7 simple, wart-like papillae (verrucae), 2–3 µm high; upper external marginal cells quadrate, short-rectangular or oblate, (13)16–24(25.5) × (12)16–24(32) µm [length/width ratio 0.5–2.5], thick-walled, walls 3.2 µm thick; middle lamina translucent, collenchymatous, trigones scarcely to strongly developed, rarely absent; middle laminal cells usually polygonal or short-rectangular, sometimes quadrate or oblate, (16)20–32(40) × (11)16–24(35) µm, thin-walled, usually equally thin in all cells from costa to margin, occasionally thicker near the costa than in the margin, higher near the costa than towards the margins, bearing 3–9 simple, wart-like papillae (verrucae), bulging in both faces; middle external marginal cells short-rectangular, quadrate, oblate or more rarely long-rectangular, (13)16–28(50) × (13)16–23(35) µm [length/width ratio (0.5)0.8–1.8(3.6)], thick-walled, walls 3.2(4.7) µm thick, smooth to scarcely papillose; basal lamina not collenchymatous; basal median laminal cells rectangular, (35)50–90(110) × (13)20–32(40) µm, thin-walled, that collapse very easily, smooth; basal external marginal cells longer and narrower, with 1–2 rows ascending the lamina, (20)40–80(105) × (8)11–16(24) µm [length/width ratio, 2–8.7(14.2)], thin-walled, smooth; basal yuxtacostal cells rectangular (50)70–100(150) × (8)16–24(32) µm, thin-walled, and that do not collapse easily. Autoecious. Perigonia along the stem. Perichaetia apical and subapical. Perichaetial leaves undifferentiated or slightly differentiated, more widely elliptical than median leaves or more rarely lingulate, spathulate or ovate, frequently convolute, (2.0)3.0–3.5(4.5) × (0.8)1.0–1.5 mm. Seta erect, 8.0–12.4 mm long, straight or sinistrorse below, dextrorse above, yellowish to orange, smooth, in cross-section with epidermal cell walls thickened, cortex cell walls usually homogenously thickened and sometimes thicker on the outside part and gradually thinning to the inside, central strand present, 16.0–25.0 µm in diameter. Capsule erect, stegocarpous, exerted; theca cylindrical, 3.0–3.9 × 0.5–0.7 mm, orange; exothecial cells rectangular, disposed in rows, frequently with longitudinal walls thicker than transversal, sometimes thin-walled; annulus falling only when dissecting, formed by two rows of vesiculose cells, the upper one 16.0–22.0 µm long, reddish externally, and 40.0–47.6 µm, hyaline, when observed in top view; stomata phaneroporous, in one or two rows in the neck of the capsule; peristome basal membrane tessellated, 0.7–0.9 mm long (measured from the inner side of the capsule), with a reticulate pattern where the lumina are delimited by strongly developed muri ornamented with globose, densely arranged clusters of ear-like lobes (auricles), and 32 filiform peristome teeth spirally twisted in two turns, (0.4)0.7–0.9 mm long, orange, densely papillose, with non-grouped, long baculate papillae; operculum long conical, (1.3)1.5–2.3 mm long, not systylious, with spirally twisted cells. Calyptra cucullate, smooth, 3.5–5.3 mm long, brownish yellow. Spores (11)14–20 µm in diameter, finely and irregularly papillose. Leaf color reaction with KOH yellowish.

- Etymology. The specific epithet murciana refers to the Spanish Region of Murcia, the first and so far only area where the species has been found, located along the Mediterranean Sea. Although it may eventually be detected in other areas, the name highlights the locality where the species was first discovered.

- Paratypes. SPAIN: Murcia province, Revolcadores massif, ascent to Pico de los Obispos, 38.071260 N, 2.268584 W, 1814 m, soil accumulated between the roots of Pinus nigra, 1 August 2023, R.M. Ros & O. Werner s.n. (sample ID number 443), (MUB 63617); idem, 38.071937 N, 2.270092 W, 1775 m, alkaline soil accumulated among Pinus nigra roots, 15 June 2023, R.M. Ros & O. Werner s.n. (sample ID number 365), (MUB 63608); idem, 38.072343 N, 2.270303 W, 1749 m, alkaline soil at the base of a Pinus nigra, 1 August 2023, R.M. Ros & O. Werner s.n. (sample ID number 440), (MUB 63609); idem, 38.071978 N, 2.269992 W, 1755 m, alkaline soil accumulated among exposed Pinus nigra roots, 1 August 2023, R.M. Ros & O. Werner s.n. (sample ID number 446), (MUB 63610); idem, 38.072372 N, 2.270413 W, 1743 m, alkaline soil accumulated over exposed Pinus nigra roots, 1 August 2023, R.M. Ros & O. Werner s.n. (sample ID number 447), (MUB 63611); idem, 38.082104 N, 2.24175 W, 1540 m, thin layer of soil over limestone, 15 July 2025, R.M. Ros, O. Werner &A. Calvo-Torralbo s.n. (sample ID number 900), (MUB 63612); idem, 38.0722770 N, 2.2699746 W, 1759 m, on soil deposited over a limestone bedrock, 16 July 2025, R.M. Ros, O. Werner &A. Calvo-Torralbo s.n. (sample ID number 907), (MUB 63613); idem, 38.0722770 N, 2.2699746 W, 1759 m, soil deposited over a limestone bedrock, 16 July 2025, R.M. Ros, O. Werner &A. Calvo-Torralbo s.n. (sample ID number 908), (MUB 63614); idem, 38.071584 N, 2.269359 W, 1782 m, soil in a crevice of limestone rock, 16 July 2025, R.M. Ros, O. Werner &A. Calvo-Torralbo s.n. (sample ID number 909), (MUB 63615); idem, 38.070131 N, 2.264594 W, 1950 m, soil in a crevice of limestone rock, 16 July 2025, R.M. Ros, O. Werner &A. Calvo-Torralbo s.n. (sample ID number 912), (MUB 63616).

- Distribution and habitat. Tortula murciana is so far restricted to the Revolcadores Massif (Murcia province, SE Spain), where it is relatively abundant on the slopes of Pico de los Obispos, the highest peak in the region (2014 m a.s.l.). The massif has a karstic relief on dolomites and dolomitic limestones, resulting in calcium-rich soils [51]. At higher elevations, the vegetation is dominated by Pinus nigra J.F. Arnold, with Quercus rotundifolia Lam., Q. coccifera L., and a shrub layer of Berberis hispanica Boiss. & Reut, Erinacea anthyllis Link., and Genista scorpius DC. These areas consist of wind-exposed rocky slopes that receive 500–700 mm/m2 of rainfall. The species occurs in soil accumulated in rock crevices and among exposed roots of P. nigra, microhabitats that protect it from snowmelt runoff and strong insolation. It has been recorded between 1540 and 1950 m a.s.l. In the same habitats T. inermis, T. mucronifolia, and T. subulata also occur.

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Discussion

| 1. Upper laminal cells strongly papillose, papillae branched, C-shaped; leaf lamina opaque | 2 |

| 1. Upper laminal cells smooth or slightly papillose, papillae simple, conic or wart-like; leaf lamina translucent | 4 |

| 2. Leaves regularly twisted around the stem when dry; leaf margins recurved from base to apex; leaf border undifferentiated | T. inermis |

| 2. Leaves generally spirally arranged independently from each other when dry; leaf margins plane or recurved from base to 2/3 of the leaf; leaf border variable, from distinctly differentiated from base to at least mid-leaf, to almost undifferentiated | 3 |

| 3. Leaf margins bistratose; leaf border distinctly differentiated from the base to at least mid-leaf; middle laminal cells (7.5)10.0–16.3(17.5) µm wide; peristome basal membrane (580)1090–1316(1644) µm long | T. schimperi |

| 3. Leaf margins unistratose; leaf border variable, from distinctly differentiated from base to at least mid-leaf, to almost absent; middle laminal cells (13.8)15.0–20.0 µm wide; peristome basal membrane (400)750–1000(1445) long | T. subulata s.l. |

| 4. Upper laminal cells smooth or with 1–2 simple, conic papillae, 1 µm high, extremely scarce and restricted to a few cells; leaves L/W ratio of 1.7–3.6(4.8); costa width at mid-leaf 45.5–87.5(114.0) µm; upper laminal cells (11)14–20(28) µm wide; peristome basal membrane 0.30–0.74(1.0) mm long, with ornamentation consisting of linear clusters of ear-like lobes (auricles), sparsely arranged | T. mucronifolia |

| 4. Upper laminal cells with (0)2–7 simple, wart-like papillae, 1–3 µm high; leaves L/W ratio of 3.9–5.1; costa width at mid-leaf (55.0)70.0–140.0 µm; upper laminal cells 13–28(32) µm wide; peristome basal membrane 0.50–0.90 mm long, with ornamentation consisting of globose clusters of ear-like lobes (auricles) | 5 |

| 5. Plants 1–3 cm tall; leaves broadly lingulate or linear-lingulate to narrowly lanceolate, 3.9–7.0 mm long, with acute to long-acuminate apex and entire, crenulate or somewhat irregularly dentate margins towards the apex; leaf border always present, poorly developed, yellowish, extending up to 2/3 of the leaf, with 3–4 rows of cells, that are elongated in the middle and basal parts and quadrate to short-rectangular distally; ventral epidermal cells of the costa at mid-leaf (seen in cross-section) quadrate to elliptical or oblate, no or very slightly inflated, 11.0–19.0 × 11.0–14.0 µm; middle laminal cells (seen in cross-section) slightly higher near the costa (until 28 µm) as in the margin (until 20 µm); dorsal epidermal cells of the costa at mid-leaf smooth; theca 3.8–10.0 mm long; basal membrane of the peristome with a reticulate pattern without or slightly developed muri delimiting the lumina in some areas | T. subulata (var. graeffii) |

| 5. Plants 0.3–0.5 cm tall; leaves elliptical, rarely lanceolate, lingulate or spatulate, 3.3–4.5 mm long, acute or shortly acuminate to obtuse, more rarely rounded apex and crenulate to papillose–crenulate margins at upper part; leaf border usually absent, more rarely poorly developed, not yellowish, extending up to halfway of the leaf, with 2–3 rows of elongated, smooth cells; ventral epidermal cells of the costa at mid-leaf (seen in cross-section) quadrate to spherical, inflated, 19.0–24.0 × 14.5–1.06 µm; middle laminal cells (seen in cross-section) much higher near the costa (until 32 µm) than in the margin (until 16 µm); dorsal epidermal cells of the costa at mid-leaf papillose; theca 3.0–3.9 mm long; basal membrane of the peristome with a reticulate pattern with well-developed muri delimitating the lumina | T. murciana |

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling

4.2. DNA Sequencing

4.3. Data Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zander, R.H. Genera of the Pottiaceae: Mosses of harsh environments. Bull. Buffalo Soc. Nat. Sci. 1993, 32, 1–378. [Google Scholar]

- Košnar, J.; Kolář, F. A taxonomic study of selected European taxa of the Tortula muralis (Pottiaceae, Musci) complex: Variation in morphology and ploidy level. Preslia 2009, 81, 399–421. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, J.; Feng, C. Tortula neoeckeliae (Pottiaceae, Musci), a new species from China. Bryologist 2018, 121, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, R.H. Adaptations of Ecosystems. In Macroevolutionary Systematics of the Streptotrichaceae of the Bryophyta and Application to Ecosystem Thermodynamic Stability; Zander, R.H., Ed.; Zetetic Publications: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2017; pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Zander, R.H. Seven new genera in Pottiaceae (Musci) and a lectotype for Syntrichia. Phytologia 1989, 65, 424–436. [Google Scholar]

- Brinda, J.C.; Atwood, J.J. The Bryophyte Nomenclator. Available online: https://www.bryonames.org/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Werner, O.; Ros, R.M.; Cano, M.J.; Guerra, J. Tortula and some related genera (Pottiaceae, Musci): Phylogenetic relationships based on chloroplast rps4 sequences. Plant Syst. Evol. 2002, 235, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košnar, J.; Herbstová, M.; Kolár, F.; Koutecký, P.; Kucera, J. A case study of intragenomic ITS variation in bryophytes: Assessment of gene flow and role of polyploidy in the origin of European taxa of the Tortula muralis (Musci: Pottiaceae) complex. Taxon 2012, 61, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.J.; Werner, O.; Guerra, J. A morphometric and molecular study in Tortula subulata complex (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2005, 149, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, O.; Guerra, J. Molecular phylogeography of the moss Tortula muralis Hedw (Pottiaceae) based on chloroplast rps4 gene sequence data. Plant Biol. 2004, 6, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannezhad, H.; Magdy, M.; Werner, O.; Ros, R.M. Exploring plastome diversity and molecular evolution within genus Tortula (family Pottiaceae, Bryophyta). Plants 2025, 14, 2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochyra, R.; Żarnowiec, J.; Bednarek-Ochyra, H. Census Catalogue of Polish Mosses; Polish Academy of Sciences, Institute of Botany: Kraków, Poland, 2003; pp. 1–372. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, M.J.; Gallego, M.T. The genus Tortula (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta) in South America. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2008, 156, 173–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgetts, N.G.; Söderström, L.; Blockeel, T.L.; Caspari, S.; Ignatov, M.S.; Konstantinova, N.A.; Lockhart, N.; Papp, B.; Schröck, C.; Sim-Sim, M.; et al. An annotated checklist of bryophytes of Europe, Macaronesia and Cyprus. J. Bryol. 2020, 42, 1–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleffi, M.; Cogoni, A.; Poponessi, S. An updated checklist of the bryophytes of Italy, including the Republic of San Marino and Vatican City State. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 157, 1259–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugués, M.; Ruiz, E. Catàleg de les Molses de l’Espanya Peninsular. Available online: https://webs.uab.cat/briologia/cataleg-de-les-molses-de-lespanya-peninsular/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Ros, R.M.; Mazimpaka, V.; Abou-Salama, U.; Aleffi, M.; Blockeel, T.L.; Brugués, M.; Cros, R.M.; Dia, M.G.; Dirkse, G.M.; Draper, I.; et al. Mosses of the Mediterranean, an annotated checklist. Cryptog. Bryol. 2013, 34, 99–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The Mediterranean: A Biodiversity Hotspot Under Threat. Available online: https://iucn.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/the_mediterranean_a_biodiversity_hotspot_under_threat_factsheet_en.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Medail, F.; Quezel, P. Hot-Spots analysis for conservation of plant biodiversity in the Mediterranean Basin. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1997, 84, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, J.-P. Mosses and Liverworts of the Mediterranean: An Illustrated Field Guide; Books on Demand: Hamburg, Germany, 2010; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, M.J.; Velten, J.; Mishler, B.D. Desiccation tolerance in bryophytes: A reflection of the primitive strategy for plant survival in dehydrating habitats? Integr. Comp. Biol. 2005, 45, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, J.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.J.; Ros, R.M. On the degree of adaptation of the moss flora and vegetation in gypsiferous zones of the south-east Iberian Peninsula. J. Bryol. 1992, 17, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M.C.F.; Oliver, M.J.; Wood, A.J.; Alpert, P.; Stark, L.R.; Cleavitt, N.L.; Mishler, B.D. Desiccation-tolerance in bryophytes: A review. Bryologist 2007, 110, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, R.H.; Eckel, P.M. Tortula Hedwig. In Flora of North America North of Mexico; Bryophyta, Part 1; Flora of North America Editorial Committee, Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 27, pp. 586–603. [Google Scholar]

- Casas, C.; Brugués, M.; Cros, R.M.; Sérgio, C. Handbook of Mosses of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands; Institut d’Estudis Catalans: Barcelona, Spain, 2006; p. 349. [Google Scholar]

- Thouvenot, L. Flore bibliographique des bryophytes du Département des Pyrénées-orientales. Nat. Ruscinonensia 2002, 11, 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Casas, C.; Brugués, M.; Cros, R.M.; Ruiz, E.; Barrón, A. Checklist of mosses of the Spanish Central Pyrenees. Cryptog. Bryol. 2009, 30, 33–65. [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi, M.; Kürschner, H.; Privitera, M. Syntaxonomy, life forms and life strategies of the bryophyte vegetation of the Carnic Alps (NE Italy). Nova Hedwig. 2013, 96, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rams, S.; Werner, O.; Ros, R.M. Updated checklist of the bryophytes from Sierra Nevada Mountains (S of Spain). Cryptog. Bryol. 2014, 35, 261–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legland, T.; Garraud, L. Mousses et Hépatiques des Alpes Françaises. Etat des Connaissances, Atlas, Espèces Protégées; Conservatoire Botanique National Alpin: Gap, France, 2018; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.J.E. Bryophyte Ecology; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1982; pp. x+511. [Google Scholar]

- Glime, J.M. Adaptive Strategies: Growth and Life Forms (Chapt. 4–5). Available online: http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Cano, M.J. Typification of the names of some infraspecific taxa in the Tortula subulata complex (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta) and their taxonomic disposition. Taxon 2007, 56, 949–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.J. Tortula. In Flora Briofítica Ibérica; Guerra, J., Cano, M.J., Ros, R.M., Eds.; Universidad de Murcia—Sociedad Española de Briología: Murcia, Spain, 2006; Volumen III, pp. 146–176. [Google Scholar]

- Warnstorf, C. Der Formenkreis der Tortula subulata (L.) Hedw. und deren Verhältnis zu Tortula mucronifolia Schwgr. Hedwigia 1912, 52, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.J.E. The Moss Flora of Britain and Ireland, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; pp. i–xii, 1–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Nyholm, E. Illustrated Moss Flora of Fennoscandia; II. Musci. Fasc. 2; CWK Gleerup: Lund, Sweden, 1956; pp. 85–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hending, D. Cryptic species conservation: A review. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2025, 100, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, J.; Klugmann, F.; Hentschel, J.; Schneider, H. DNA taxonomy, cryptic speciation and diversification of the Neotropical-African liverwort, Marchesinia brachiata (Lejeuneaceae, Porellales). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2009, 53, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, A.J. Biogeographic patterns and cryptic speciation in bryophytes. J. Biogeogr. 2001, 28, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, A.; Kasana, S.; Uniyal, P.L. From barcodes to genomes: A new era of molecular exploration in bryophyte research. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1500607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, R.; Lara, F.; Goffinet, B.; Garilleti, R.; Mazimpaka, V. Integrative taxonomy successfully resolves the pseudo-cryptic complex of the disjunct epiphytic moss Orthotrichum consimile s.l. (Orthotrichaceae). Taxon 2012, 61, 1180–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, R.; Lara, F.; Goffinet, B.; Garilleti, R.; Mazimpaka, V. Unnoticed diversity within the disjunct moss Orthotrichum tenellum s.l. validated by morphological and molecular approaches. Taxon 2013, 62, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, M.A.M. Opportunities and challenges presented by cryptic bryophyte species. Telopea 2020, 23, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.J.; Jiménez, J.A.; Martínez, M.; Hedenäs, L.; Gallego, M.T.; Rodríguez, O.; Guerra, J. Integrative taxonomy reveals hidden diversity in the Aloina catillum complex (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta). Plants 2024, 13, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köckinger, H.; Werner, O.; Ros, R.M. A new taxonomic approach to the genus Oxystegus (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta) in Europe based on molecular data. Nova Hedwigia. Beiheft 2010, 138, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, M.J.; Jiménez, J.F.; Alonso, M.; Jiménez, J.A. Untangling Pseudocrossidium crinitum s.l. (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta) through molecular and morphometric analysis. Nova Hedwig. 2016, 102, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köckinger, H.; Hedenäs, L. A farewell to Tortella bambergeri (Pottiaceae) as understood over the last decades. J. Bryol. 2017, 39, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köckinger, H.; Hedenäs, L. The supposedly well-known carbonate indicator Tortella tortuosa (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta) split into eight species in Europe. Lindbergia 2023, 2023, 24903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedenäs, L. Another Fennoscandian Tortella species with fragile leaves, Tortella fragmenta (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta). Lindbergia 2025, 2025, e026226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Ramo Jiménez, A.; Guillén Mondéjar, F. Actualización del Inventario de Lugares de Interés Geológico en la Región de Murcia-2009. Available online: https://info.igme.es/ielig/documentacion/mu/mu017/documentos/d-mu017-01.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Mishler, B.D. Tortula Hedw., nom. cons. In The Moss Flora of Mexico; Sharp, A.J., Crum, H., Eckel, P.M., Eds.; The New York Botanical Garden: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 1, pp. 319–350. [Google Scholar]

- Steere, W.C. Tortula in North America north of Mexico. Bryologist 1940, 43, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnstorf, C. Kryptogamenflora der Mark Brandenburg und angrenzender Gebiete. Abteilung Moose. Zweiter Band. In Laubmoose; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Leipzig, Germany, 1906; Volume 2, pp. [i]–xii, [1]–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Crundwell, A.C. Further notes on Tortula subulata var. graeffii. Trans. Brit. Bryol. Soc. 1956, 3, 125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Buck, W.R.; Goffinet, B. A new checklist of the mosses of the continental United States and Canada. Bryologist 2024, 127, 484–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnell, N.; Hassel, K.; Goldberg, I.; Huttunen, S.; Bjarnason, Á.H.; Blom, H.H.; Hallingbäck, T.; Hedenäs, L.; Høitomt, T.; Pihlaja, K.; et al. An annotated checklist of bryophytes of the Nordic countries. Lindbergia 2025, 2025, e025337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatova, E.A.; Tubanova, D.Y.; Tumurova, O.D.; Goryunov, D.V.; Kuznetsova, O.I. When the plant size matters: A new semi-cryptic species of Dicranum from Russia. Arctoa 2015, 24, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.S.; Kruijer, J.D.; Stech, M. DNA barcoding of Arctic bryophytes: An example from the moss genus Dicranum (Dicranaceae, Bryophyta). Polar Biol. 2014, 37, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, O.; Jiménez, J.A.; Ros, R.M. The systematic position of the moss Kingiobryum paramicola (Pottiaceae) based on molecular and morphological data. Bryologist 2004, 107, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbritter, H.; Ulrich, S.; Grímsson, F.; Weber, M.; Zetter, R.; Hesse, M.; Buchner, R.; Svojtka, M.; Frosch-Radivo, A. Illustrated Pollen Terminology, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. XVIII+483. [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz Laín, C. Glosario de términos palinológicos. Lazaroa 2004, 25, 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm, B.; Malcolm, N. Mosses and Other Bryophytes—An Illustrated Glossary, 2nd ed.; Micro-Optics Press: Nelson, New Zealand, 2006; pp. [i]–iv+1–336. [Google Scholar]

- Magill, R.E. Glossarium Polyglottum Bryologiae. A multilingual glossary for bryology. In Monographs in Systematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1990; Volume 33, p. 297. [Google Scholar]

- Avise, J.C. Phylogeography: The History and Formation of Species; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- van Valen, L. A new evolutionary law. Evol. Theory 1973, 1, 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zander, R.H. Shannon entropy and informational redundancy in minimally monophyletic bryophyte genera. Plants 2025, 14, 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, R.H. Structural Monophyly Abstractions. Res Botanica Technical Report 2025-09-30. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/144227468/STRUCTURAL_MONOPHYLY_ABSTRACTIONS (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Zander, R.H. Evolutionary leverage of dissilient genera of Pleuroweisieae (Pottiaceae) evaluated with Shannon-Turing analysis. Hattoria 2021, 12, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M., Gelfand, D., Sninsky, J., White, T., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, S.H.; Ward, L.J.; Li, X.; Chittaranjan, S. Attenuation of PCR inhibition in the presence of plant compounds by addition of BLOTTO. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 2567–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K. SeqState—Primer design and sequence statistics for phylogenetic DNA data sets. Appl. Bioinform. 2005, 4, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, M.P.; Ochoterena, H. Gaps as characters in sequence-based phylogenetic analyses. Syst. Biol. 2000, 49, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F. MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1572–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Larget, B.; Alfaro, M.E. Bayesian Phylogenetic Model Selection Using Reversible Jump Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004, 21, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöver, B.C.; Müller, K.F. TreeGraph 2: Combining and visualizing evidence from different phylogenetic analyses. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T. inermis | T. mucronifolia | T. murciana | T. schimperi | T. subulata s.l. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0048 | 0.0028 | 0.0000 | 0.0124 | 0.0135 |

| T. inermis | T. mucronifolia | T. murciana | T. schimperi | T. subulata s.l. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. inermis | - | - | - | - | - |

| T. mucronifolia | 0.0501 | - | - | - | - |

| T. murciana | 0.0191 | 0.0530 | - | - | - |

| T. schimperi | 0.0375 | 0.0468 | 0.0402 | - | - |

| T. subulata s.l. | 0.0144 | 0.0486 | 0.0226 | 0.0353 | -- |

| Character | T. murciana | T. mucronifolia | T. subulata var. graeffii |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants size (stem) | 0.3–0.5 cm | 0.5–1.6 cm | 1.0–3.0 cm |

| Stem tomentum | abundant | absent or sparse | sparse to abundant |

| Leaves shape | usually elliptical, rarely lanceolate, lingulate or spathulate | usually elliptical, lingulate or ovate, rarely lanceolate or spathulate | broadly lingulate, linear-lingulate or narrowly lanceolate |

| Median leaves size (L × W) | 3.3–4.5 × 0.7–1.6 mm | (1.7)2.5–4.0(5.9) × (0.6)0.7–1.4 mm | 3.9–7.0 × 0.9–2.0 mm |

| Median leaves L/W ratio | (2.3)2.6–4.5(5.9) | 1.7–3.6(4.8) | 3.9–5.1 |

| Median leaves apex | acute or shortly acuminate to obtuse, more rarely rounded | acute or obtuse to rounded | acute to long-acuminate |

| Median leaf margins at upper part | crenulate to papillose–crenulate | entire to crenulate | entire, crenulate or somewhat irregularly dentate towards the apex |

| Median leaves border | usually absent, more rarely poorly developed, non-yellowish, extending up to halfway of the leaf, with 2–3 rows of elongated, smooth cells | usually absent, more rarely poorly developed, yellowish, extending up to halfway of the leaf, with 1–3 rows of elongated, smooth or more rarely, scarcely papillose cells | always present, poorly developed, usually yellowish, extending up to 2/3 of the leaf, with 3–4 rows of cells, that are elongated in the middle and basal parts and quadrate to short-rectangular distally |

| Apiculus apical cell | usually hyaline, very frequently deciduous | usually yellowish, sometimes deciduous | usually greenish, sometimes deciduous |

| Apiculus apical cell length | 50–100 µm | 30–70 µm | 40–90 µm |

| Costa width at mid-leaf | (55.0)80.0–140.0 µm | 45.5–87.5(114.0) µm | 70.0–100.0 µm |

| Dorsal epidermal cells of the costa at mid-leaf | slightly to strongly papillose | smooth | smooth |

| Ventral epidermal cells of the costa at the upper part of the leaf (below the most apical elongated cells) | quadrate to rectangular, inflated and papillose | quadrate to rectangular, not or slightly inflated and smooth | rectangular, inflated and papillose |

| Ventral epidermal cells of the costa at mid-leaf (seen in cross-section) | quadrate to spherical, inflated, 19.0–24.0 × 14.5–16.0 µm | quadrate to short-rectangular, elliptical or oblate, non or very slightly inflated, 9.0–13.0(20.0) × 8.0–13.0(20.0) µm | quadrate to elliptical or oblate, not or very slightly inflated, 11.0–19.0 × 11.0–14.0 µm |

| Upper laminal cells width | (14)16–28(32) µm | (11)14–20(28) µm | 13–27 µm |

| Upper laminal cells papillosity | 3–7 simple, wart-like papillae (verrucae), 2 3 µm high | absent or, if present at all, extremely scarce and restricted to a few cells, with 1–2 simple, conic papillae, 1 µm high | 2–8 conic, wart-like papillae (verrucae), 1–3 µm high |

| Middle laminal cells width | (11)16–24(35) µm | (10)14–28 µm | 16–27 µm |

| Middle laminal cells papillosity | 3–9 simple, wart-like papillae (verrucae) | smooth (very rarely with 1–2 simple conic papillae) | 4–9 simple, wart-like papillae (verrucae) |

| Middle laminal cells height (seen in cross-section) | higher near the costa (until 32 µm) than in the margin (until 16 µm) | similar height or slightly different near the costa (until 22 µm) as in the margin (until 16 µm) | slightly higher near the costa (up to 28 µm) than in the margin (up to 20 µm) |

| Theca length | 3.0–3.9 mm | 2.0–3.6(6.0) mm | 3.8–10.0 mm |

| Peristome basal membrane length | 0.70–0.90 mm | 0.30–0.74(1.0) mm | 0.50–0.85 mm |

| Pattern of the tessellated peristome basal membrane | reticulate with strongly developed muri delimiting the lumina | reticulate without or slightly developed muri delimiting the lumina | reticulate, without or slightly developed muri delimiting the lumina in some areas |

| Ornamentation of the muri | globose clusters of ear-like lobes (auricles), densely arranged | linear clusters of ear-like lobes (auricula), sparsely arranged | globose clusters of ear-like lobes (auricles), sparsely arranged |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ros, R.M.; Werner, O.; Muñoz, J.; Magdy, M. Tortula murciana (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta), a New Species from Mediterranean Mountains. Plants 2025, 14, 3861. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243861

Ros RM, Werner O, Muñoz J, Magdy M. Tortula murciana (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta), a New Species from Mediterranean Mountains. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3861. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243861

Chicago/Turabian StyleRos, Rosa M., Olaf Werner, Jesús Muñoz, and Mahmoud Magdy. 2025. "Tortula murciana (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta), a New Species from Mediterranean Mountains" Plants 14, no. 24: 3861. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243861

APA StyleRos, R. M., Werner, O., Muñoz, J., & Magdy, M. (2025). Tortula murciana (Pottiaceae, Bryophyta), a New Species from Mediterranean Mountains. Plants, 14(24), 3861. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243861