Pangenome-Wide Identification, Evolutionary Analysis of Maize ZmPLD Gene Family, and Functional Validation of ZmPLD15 in Cold Stress Tolerance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

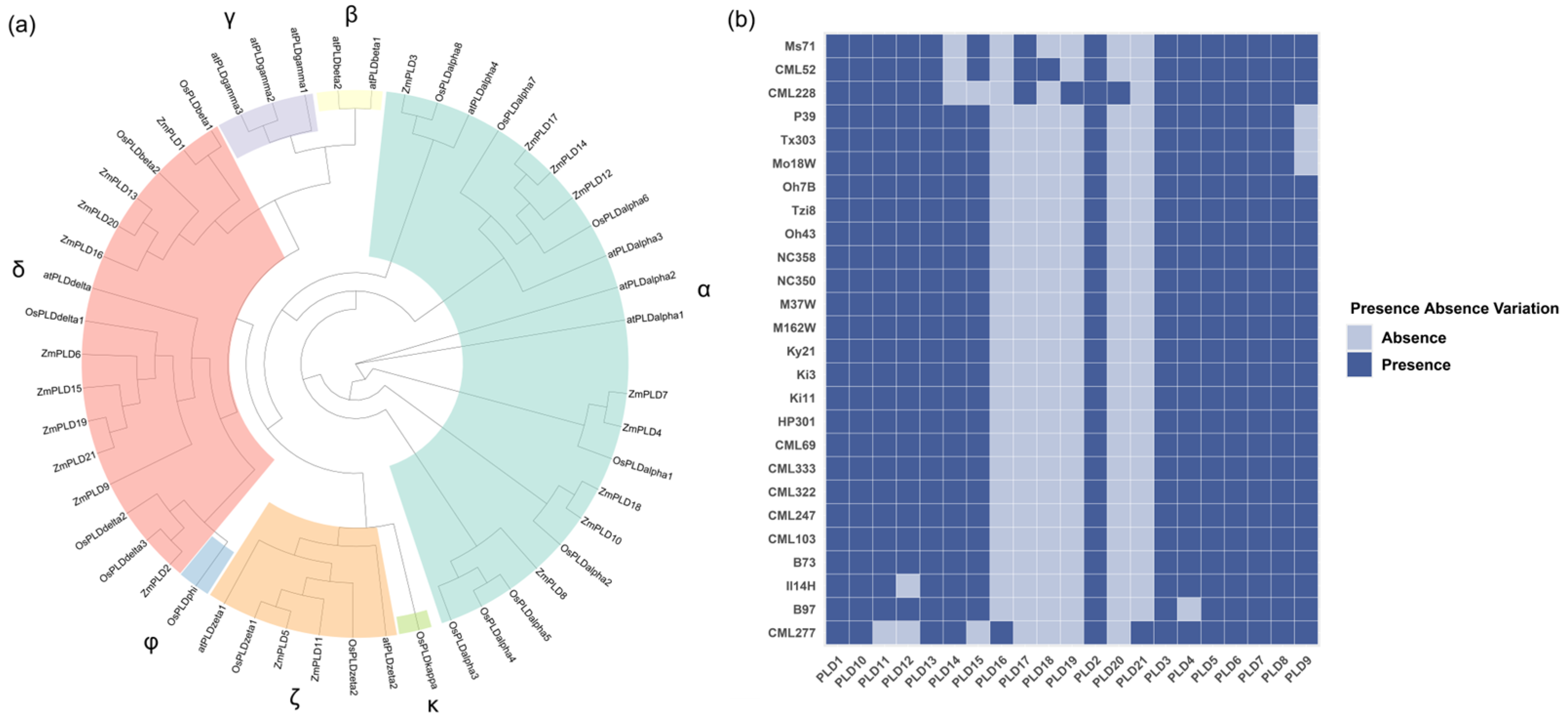

2.1. Pan-Genome-Wide ZmPLD Identification

2.2. ZmPLD Is Subjected to Different Selection Pressures Among Maize Varieties

2.3. Expression and Structure of ZmPLD15 Genes Are Affected by SV in the Promoters

2.4. Impact of Mutations on ZmPLD15 Protein Spatial Structure and Substrate Binding Free Energy

2.5. Impact of ZmPLD15 Overexpression on Cold Stress Tolerance in Maize

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of Maize PLD Gene Family

4.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Presence/Absence Variation in ZmPLD Gene Family

4.3. Ka/Ks Calculation

4.4. Expression and Structure of ZmPLD15 Genes Are Affected by SV in the Promoters

4.5. Impact of Mutations on ZmPLD15 Protein Spatial Structure and Substrate Binding Free Energy

4.6. Impact of ZmPLD15 Overexpression on Cold Stress Tolerance in Maize

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, U.; Lu, S.; Fadlalla, T.; Iqbal, S.; Yue, H.; Yang, B.; Hong, Y.; Wang, X.; Guo, L. The functions of phospholipases and their hydrolysis products in plant growth, development and stress responses. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, R.; Quinto, C. Phospholipase Ds in plants: Their role in pathogenic and symbiotic interactions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 173, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Fan, R.; Yao, S.; Lou, H.; Li, J.; Guo, L.; Wang, X. Non-specific phospholipase Cs and their potential for crop improvement. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, eraf334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, D.; Qin, H.; Yu, Z. Integration of hepatic lipidomics and transcriptomics reveals dysregulation of lipid metabolism in a golden hamster model of visceral leishmaniasis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1595702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Figueiredo, J.; Laureano, G.; Machado, A.; Arrabaca, J.D.; Duarte, B.; Figueiredo, A.; Matos, A.R. Membrane remodelling and triacylglycerol accumulation in drought stress resistance: The case study of soybean phospholipases A. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 169, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, W.; Fang, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, F.; Sun, T.; Xiang, L.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Phospholipase Ds in Perennial Ryegrass Highlights LpABFs-LpPLDdelta3 Cascade Modulated Osmotic and Heat Stress Responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Bayaraa, U.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, O.R. Overexpression of the patatin-related phospholipase A gene, PgpPLAIIIbeta, in ginseng adventitious roots reduces lignin and ginsenoside content while increasing fatty acid content. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 221, 109602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, N.; Rui, C.; Fan, Y.; Wang, J.; Han, M.; Wang, Q.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; et al. Genome-wide expression analysis of phospholipase A1 (PLA1) gene family suggests phospholipase A1-32 gene responding to abiotic stresses in cotton. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 1058–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Tyagi, K.; Roy, A. Recent advances in understanding the molecular role of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C gamma 1 as an emerging onco-driver and novel therapeutic target in human carcinogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1876, 188619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.; Deepika; Biswas, D.K.; Chandrasekar, R.; Singh, A. Genome-wide identification, structure analysis and expression profiling of phospholipases D under hormone and abiotic stress treatment in chickpea (Cicer arietinum). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 169, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y. Headgroup biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine in seed plants. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 82, 101091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, S.; Yao, S.; Li, X.; Jia, Q.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. Nonspecific phospholipases C3 and C4 interact with PIN-FORMED2 to regulate growth and tropic responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 2310–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Yang, B.; Li, J.; Tang, S.; Tang, S.; Kim, S.C.; Wang, X. Phosphatidic acid signaling in modulating plant reproduction and architecture. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Wang, X. The Arabidopsis phospholipase D family. Characterization of a calcium-independent and phosphatidylcholine-selective PLD zeta 1 with distinct regulatory domains. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Lin, F.; Xue, H.W. Genome-wide analysis of the phospholipase D family in Oryza sativa and functional characterization of PLD beta 1 in seed germination. Cell Res. 2007, 17, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W. Genomic analysis of phospholipase D family and characterization of GmPLDαs in soybean (Glycine max). J. Plant Res. 2012, 125, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Cao, B.; Han, N.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, S.F.; Li, W.C.; Fu, F.L. Phospholipase D family and its expression in response to abiotic stress in maize. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 81, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, J.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, P.; Xu, Y. Structural insights into phospholipase D function. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 81, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Violot, S.; Abousalham, A.; Noiriel, A. A new bacterial phospholipase D with specificity for phosphatidylethanolamine over phosphatidylcholine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 304, 140578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.C.; Yao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X. Phospholipase Ddelta and phosphatidic acid mediate heat-induced nuclear localization of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 112, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, D.M.; Yu, W.W.; Shi, L.L.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, Y.X.; Huang, L.P.; Qi, H.; Chen, Q.F.; Yao, N.; et al. Phosphatidic acid modulates MPK3- and MPK6-mediated hypoxia signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 889–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yao, J.; Yin, K.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, N.; et al. Populus euphratica PeNADP-ME interacts with PePLDdelta to mediate sodium and ROS homeostasis under salinity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 210, 108600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.; Goel, R.; Mishra, G. Phosphatidic acid binds to and stimulates the activity of ARGAH2 from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 185, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, P.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Lu, S.; Liu, Z.; Yang, M.; Deng, T.; Chen, L.; Qi, H.; et al. OsPLDalpha1 mediates cadmium stress response in rice by regulating reactive oxygen species accumulation and lipid remodeling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, D.; Singh, A. Plant phospholipase D: Novel structure, regulatory mechanism, and multifaceted functions with biotechnological application. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2022, 42, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Zhang, T.; Lu, Y.; Govindan, V.; Liu, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, L.; et al. Overexpression of TdNACB improves the drought resistance of rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 216, 109157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, C.; Wu, B.; Ma, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Gao, R.; Jiang, H.; Jia, C. Genome-wide characterization of LBD transcription factors in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) and the involvement of PvLBD12 in salt tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz, A.; Carolak, E.; Dutkiewicz, A.; Blachut, A.; Waszczuk, W.; Grzymajlo, K. Better together-Salmonella biofilm-associated antibiotic resistance. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2229937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, H.; Jiang, C.; Tang, C.; Nie, X.; Du, L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, P.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Kang, Z.; et al. Wheat adaptation to environmental stresses under climate change: Molecular basis and genetic improvement. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1564–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gong, J.S.; Qin, J.; Li, H.; Hou, H.J.; Zhang, X.M.; Xu, Z.H.; Shi, J.S. Phospholipids (PLs) know-how: Exploring and exploiting phospholipase D for its industrial dissemination. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 1257–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eh, T.J.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, M.; Li, J.; Lei, P.; Ji, X.; Kim, H.I.; Zhao, X.; Meng, F. The role of trehalose metabolism in plant stress tolerance. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 76, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Zhang, X.; Song, G.; Lv, Q.; Li, M.; Fu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; et al. Genetic variation in the aquaporin TONOPLAST INTRINSIC PROTEIN 4;3 modulates maize cold tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 3037–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luklova, M.; Dubois, M.; Kameniarova, M.; Plackova, K.; Novak, J.; Kopecka, R.; Karady, M.; Pavlu, J.; Skalak, J.; Jindal, S.; et al. Light Quantity Impacts Early Response to Cold and Cold Acclimation in Young Leaves of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 5030–5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pei, Y.; Zhu, F.; He, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, B.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Khan, A.; Jahangir, M.; et al. CaSnRK2.4-mediated phosphorylation of CaNAC035 regulates abscisic acid synthesis in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) responding to cold stress. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2024, 117, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, G.; Pan, Y.; Li, Q.; Miao, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, A. Brassinosteroid-signaling kinase 4 activates mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 to enhance cold stress tolerance in maize. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Piao, M.; Li, Y.; Yao, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, G.; Yang, D.; et al. Comparative Proteomics Combined with Morphophysiological Analysis Revealed Chilling Response Patterns in Two Contrasting Maize Genotypes. Cells 2022, 11, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Fu, D.; Wu, S.; Li, M.; Yang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Lai, J.; et al. Natural polymorphism of ZmICE1 contributes to amino acid metabolism that impacts cold tolerance in maize. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, R.; Kim, H.S.; Yu, T.; Zhang, A.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Yu, W.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, Q.; et al. Identification and function analysis of bHLH genes in response to cold stress in sweetpotato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 169, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Chong, K. The teosinte-derived allele COOL1 is a potential target for molecular design of chilling resilience in maize. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 1205–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Li, Z.; Shi, Y.; Fu, D.; Yin, P.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, C.; Yang, S. Natural variation in a type-A response regulator confers maize chilling tolerance. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufford, M.B.; Seetharam, A.S.; Woodhouse, M.R.; Chougule, K.M.; Ou, S.; Liu, J.; Ricci, W.A.; Guo, T.; Olson, A.; Qiu, Y.; et al. De novo assembly, annotation, and comparative analysis of 26 diverse maize genomes. Science 2021, 373, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yocca, A.E.; Lu, Z.; Schmitz, R.J.; Freeling, M.; Edger, P.P. Evolution of Conserved Noncoding Sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 2692–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Pardines, C.; Haro-Moreno, J.M.; Rodriguez-Valera, F.; Lopez-Perez, M. Extensive paralogism in the environmental pangenome: A key factor in the ecological success of natural SAR11 populations. Microbiome 2025, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: A toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2010, 8, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Guan, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, R.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; et al. Multi-Omics Analyses Offer Novel Insights into the Selection of Sugar and Lipid Metabolism During Maize Domestication and Improvement. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 2377–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, M.; Aleem, S.; Sharif, I.; Wu, Z.; Aleem, M.; Tahir, A.; Atif, R.M.; Cheema, H.M.N.; Shakeel, A.; Lei, S.; et al. Characterization of SOD and GPX Gene Families in the Soybeans in Response to Drought and Salinity Stresses. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Y.; Song, G.; Yang, D.; Xia, Z.; Sun, C.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, M.; Zhang, M.; Qi, Z.; et al. Gene expression and expression quantitative trait loci analyses uncover natural variations underlying the improvement of important agronomic traits during modern maize breeding. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 115, 772–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Li, R.Z.; Prohaska, T.A.; Hoeksema, M.A.; Spann, N.J.; Tao, J.; Fonseca, G.J.; Le, T.; Stolze, L.K.; Sakai, M.; et al. Systematic analysis of naturally occurring insertions and deletions that alter transcription factor spacing identifies tolerant and sensitive transcription factor pairs. eLife 2022, 11, e70878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurieva, B.; Kumar, D.K.; Morag, R.; Lupo, O.; Carmi, M.; Barkai, N.; Jonas, F. Disordered sequences of transcription factors regulate genomic binding by integrating diverse sequence grammars and interaction types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 8763–8777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Villegas, M.; Rebnegger, C.; Kowarz, V.; Prielhofer, R.; Mattanovich, D.; Gasser, B. Systematic sequence engineering enhances the induction strength of the glucose-regulated GTH1 promoter of Komagataella phaffii. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 11358–11374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Lei, Y.; Xu, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, M.; Tai, Y.; Han, X.; Hao, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, D.; et al. Natural variations in the promoter of ZmDeSI2 encoding a deSUMOylating isopeptidase controls kernel methionine content in maize. Mol. Plant 2025, 18, 872–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazda, V.; Bartas, M.; Bowater, R.P. Evolution of Diverse Strategies for Promoter Regulation. Trends Genet. TIG 2021, 37, 730–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, G.; Lupo, O.; Wittkopp, P.; Barkai, N. Evolution of transcription factor binding through sequence variations and turnover of binding sites. Genome Res. 2022, 32, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangappa, S.N.; Chattopadhyay, S. MYC2 differentially regulates GATA-box containing promoters during seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e25679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Jiang, H.; Li, L.; Zhai, Q.; Qi, L.; Zhou, W.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Zheng, W.; Sun, J.; et al. The Arabidopsis mediator subunit MED25 differentially regulates jasmonate and abscisic acid signaling through interacting with the MYC2 and ABI5 transcription factors. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2898–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangappa, S.N.; Maurya, J.P.; Yadav, V.; Chattopadhyay, S. The regulation of the Z- and G-box containing promoters by light signaling components, SPA1 and MYC2, in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, P.; Browse, J. The Arabidopsis JAZ2 promoter contains a G-Box and thymidine-rich module that are necessary and sufficient for jasmonate-dependent activation by MYC transcription factors and repression by JAZ proteins. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitha, K.C.; Ramu, S.V.; Pruthvi, V.; Mahesh, P.; Nataraja, K.N.; Udayakumar, M. Co-expression of AtbHLH17 and AtWRKY28 confers resistance to abiotic stress in Arabidopsis. Transgenic Res. 2013, 22, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata, M.; Mitsuda, N.; Herde, M.; Koo, A.J.; Moreno, J.E.; Suzuki, K.; Howe, G.A.; Ohme-Takagi, M. A bHLH-type transcription factor, ABA-INDUCIBLE BHLH-TYPE TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR/JA-ASSOCIATED MYC2-LIKE1, acts as a repressor to negatively regulate jasmonate signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 1641–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki-Sekimoto, Y.; Jikumaru, Y.; Obayashi, T.; Saito, H.; Masuda, S.; Kamiya, Y.; Ohta, H.; Shirasu, K. Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors JASMONATE-ASSOCIATED MYC2-LIKE1 (JAM1), JAM2, and JAM3 are negative regulators of jasmonate responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutcliffe, J.W.; Hellmann, E.; Heyl, A.; Rashotte, A.M. CRFs form protein-protein interactions with each other and with members of the cytokinin signalling pathway in Arabidopsis via the CRF domain. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 4995–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, N.; Virlouvet, L.; Riethoven, J.J.; Fromm, M.; Avramova, Z. Four distinct types of dehydration stress memory genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raines, T.; Shanks, C.; Cheng, C.Y.; McPherson, D.; Argueso, C.T.; Kim, H.J.; Franco-Zorrilla, J.M.; López-Vidriero, I.; Solano, R.; Vaňková, R.; et al. The cytokinin response factors modulate root and shoot growth and promote leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 85, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwack, P.J.; Compton, M.A.; Adams, C.I.; Rashotte, A.M. Cytokinin response factor 4 (CRF4) is induced by cold and involved in freezing tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, H.; Iwabuchi, M.; Meshi, T. Arabidopsis GARP transcriptional activators interact with the Pro-rich activation domain shared by G-box-binding bZIP factors. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.J.; Shih, M.C. Interaction of a GATA factor with cis-acting elements involved in light regulation of nuclear genes encoding chloroplast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 300, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Jin, B.; Capra, J.A.; Bush, W.S. Integration of Protein Structure and Population-Scale DNA Sequence Data for Disease Gene Discovery and Variant Interpretation. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2022, 5, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, G.; Malesys, S.; Bourgeron, T. Systematic detection of brain protein-coding genes under positive selection during primate evolution and their roles in cognition. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhou, L.; Wu, B.; Li, S.; Zha, W.; Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, L.; Shi, L.; Lin, Y.; et al. Improvement of Bacterial Blight Resistance in Two Conventionally Cultivated Rice Varieties by Editing the Noncoding Region. Cells 2022, 11, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Guo, Z. Natural uORF variation in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, T.E.; Green, A.E.; Mellor, K.C.; McKnight, A.E.; Bacher, K.; Kumar, S.; Newbold, K.; Lorenz, O.; Pohler, E.; Monshi, M.S.; et al. Naturally acquired promoter variation influences Streptococcus pneumoniae infection outcomes. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1473–1483.e1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, C.; Du, Z.; Guo, F.; Song, D.; Wang, N.; Wei, Z.; Jiang, J.; Cao, Z.; Shi, C.; et al. Transposable elements cause the loss of self-incompatibility in citrus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Di, H.; Zhang, L.; Dong, L.; Lu, Q.; Zeng, X.; Liu, X.; et al. The G protein-coupled receptor COLD1 promotes chilling tolerance in maize during germination. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, A.C.; Kromdijk, J. Can we improve the chilling tolerance of maize photosynthesis through breeding? J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3138–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Zheng, X. Metabolomics combined with physiology and transcriptomics reveal how Nicotiana tabacum leaves respond to cold stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 208, 108464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran Garzon, C.; Lequart, M.; Charras, Q.; Fournet, F.; Bellenger, L.; Sellier-Richard, H.; Giauffret, C.; Vermerris, W.; Domon, J.M.; Rayon, C. The maize low-lignin brown midrib3 mutant shows pleiotropic effects on photosynthetic and cell wall metabolisms in response to chilling. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 184, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Liang, Y.; Sang, M.; 77Zhao, G.; Song, J.; Liu, P.; Zou, C.; Chen, Z.; Ma, L.; Shen, Y. Complex regulatory network of ZmbZIP54-mediated Pb tolerance in maize. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 224, 109945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Liu, T.; Liang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zou, C.; Chen, Z.; Ma, L.; Shen, Y. GWAS and gene co-expression network analysis reveal the genetic control of seed germination under salt stress in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2025, 138, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Nielsen, R. Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.A.; Wells, D.M. An Updated Protocol for High Throughput Plant Tissue Sectioning. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.-N.; Li, Y.-L.; Sun, M.-H.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Cai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.-G. Pangenome-Wide Identification, Evolutionary Analysis of Maize ZmPLD Gene Family, and Functional Validation of ZmPLD15 in Cold Stress Tolerance. Plants 2025, 14, 3858. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243858

Li S-N, Li Y-L, Sun M-H, Sun Y, Li X, Cai Q, Wang Y, Zhang J-G. Pangenome-Wide Identification, Evolutionary Analysis of Maize ZmPLD Gene Family, and Functional Validation of ZmPLD15 in Cold Stress Tolerance. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3858. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243858

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Si-Nan, Yun-Long Li, Ming-Hao Sun, Yan Sun, Xin Li, Quan Cai, Yunpeng Wang, and Jian-Guo Zhang. 2025. "Pangenome-Wide Identification, Evolutionary Analysis of Maize ZmPLD Gene Family, and Functional Validation of ZmPLD15 in Cold Stress Tolerance" Plants 14, no. 24: 3858. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243858

APA StyleLi, S.-N., Li, Y.-L., Sun, M.-H., Sun, Y., Li, X., Cai, Q., Wang, Y., & Zhang, J.-G. (2025). Pangenome-Wide Identification, Evolutionary Analysis of Maize ZmPLD Gene Family, and Functional Validation of ZmPLD15 in Cold Stress Tolerance. Plants, 14(24), 3858. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243858