Hydration–Dehydration Dynamics in the Desiccation-Tolerant Moss Hedwigia ciliata

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

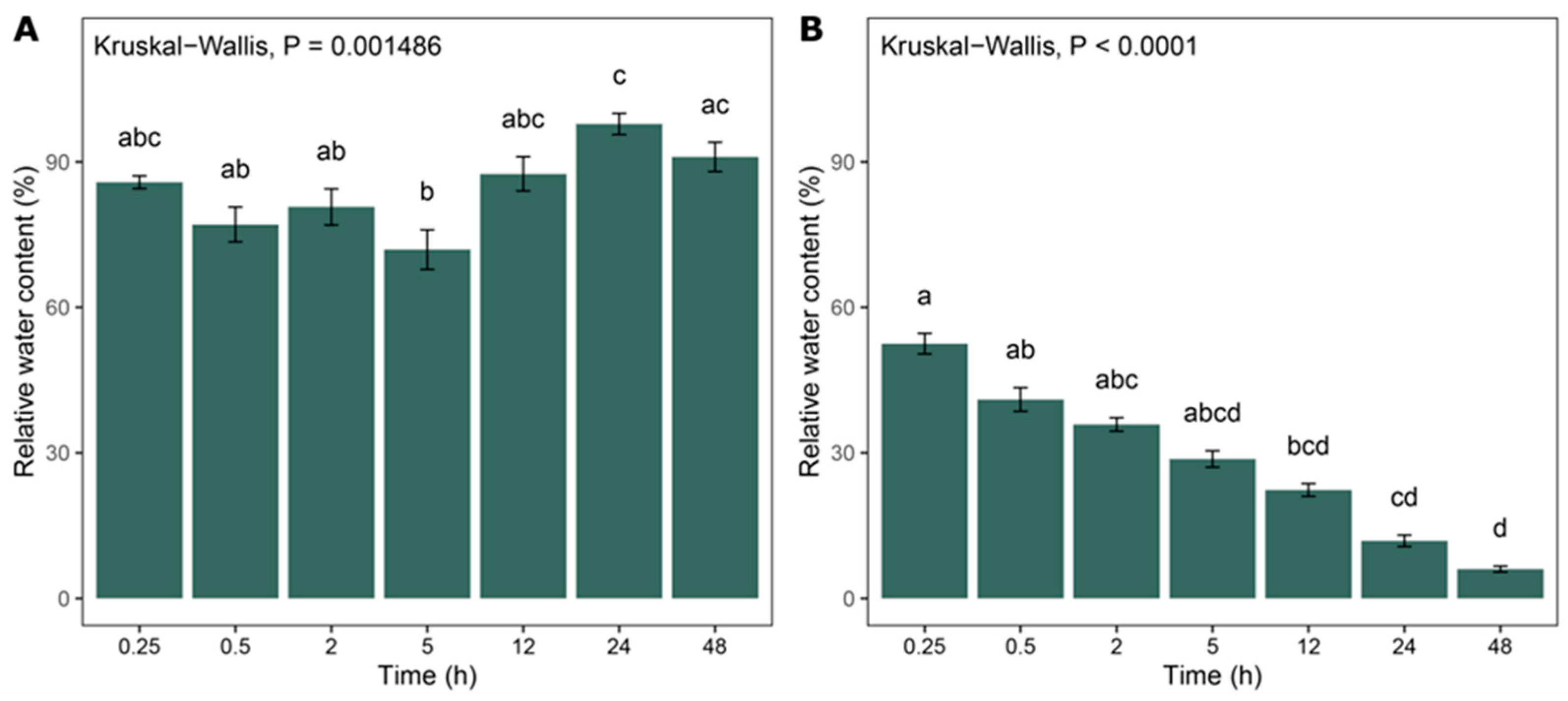

2.1. Relative Water Content

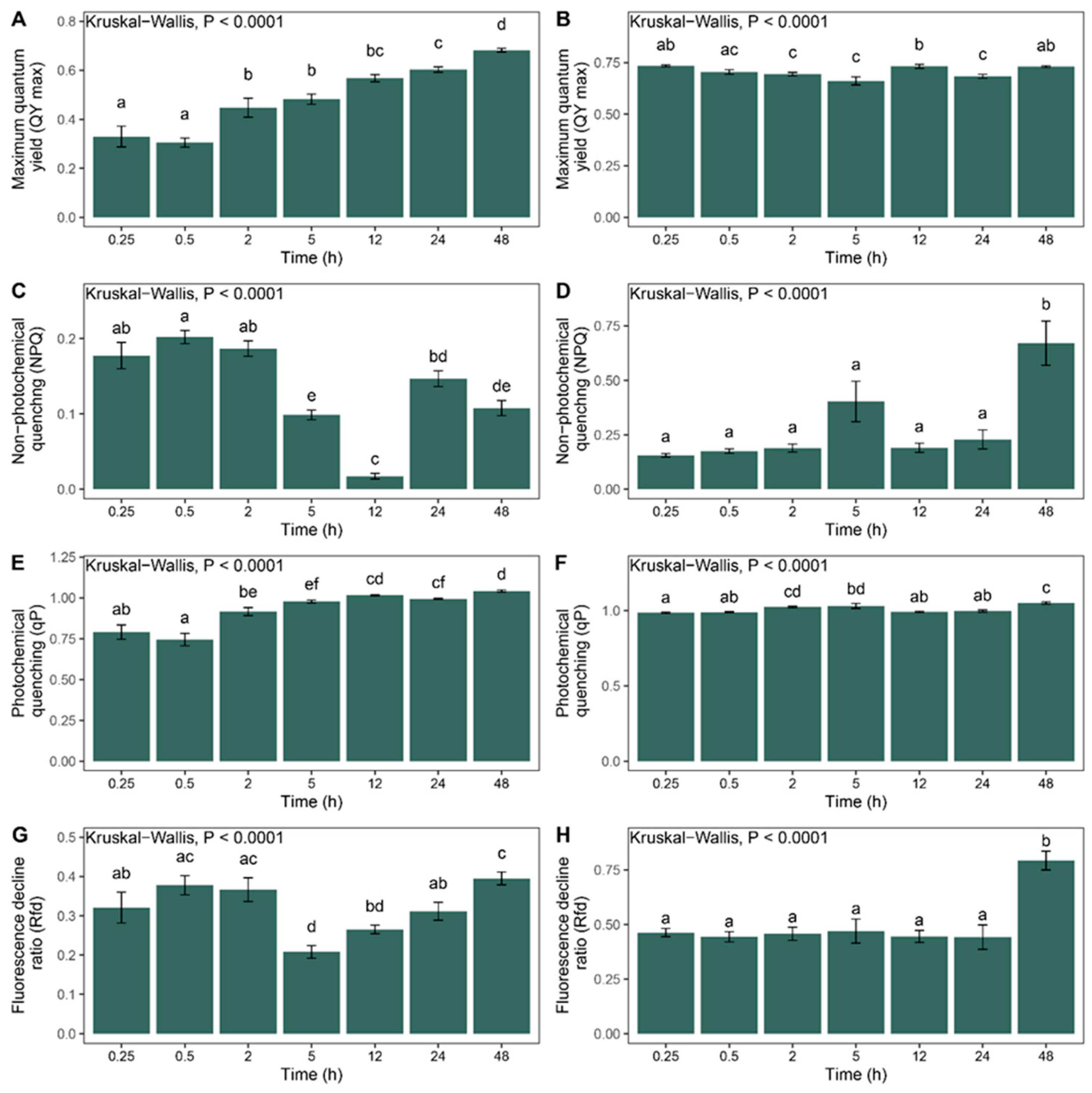

2.2. Chlorophyll Fluorescence

3. Discussion

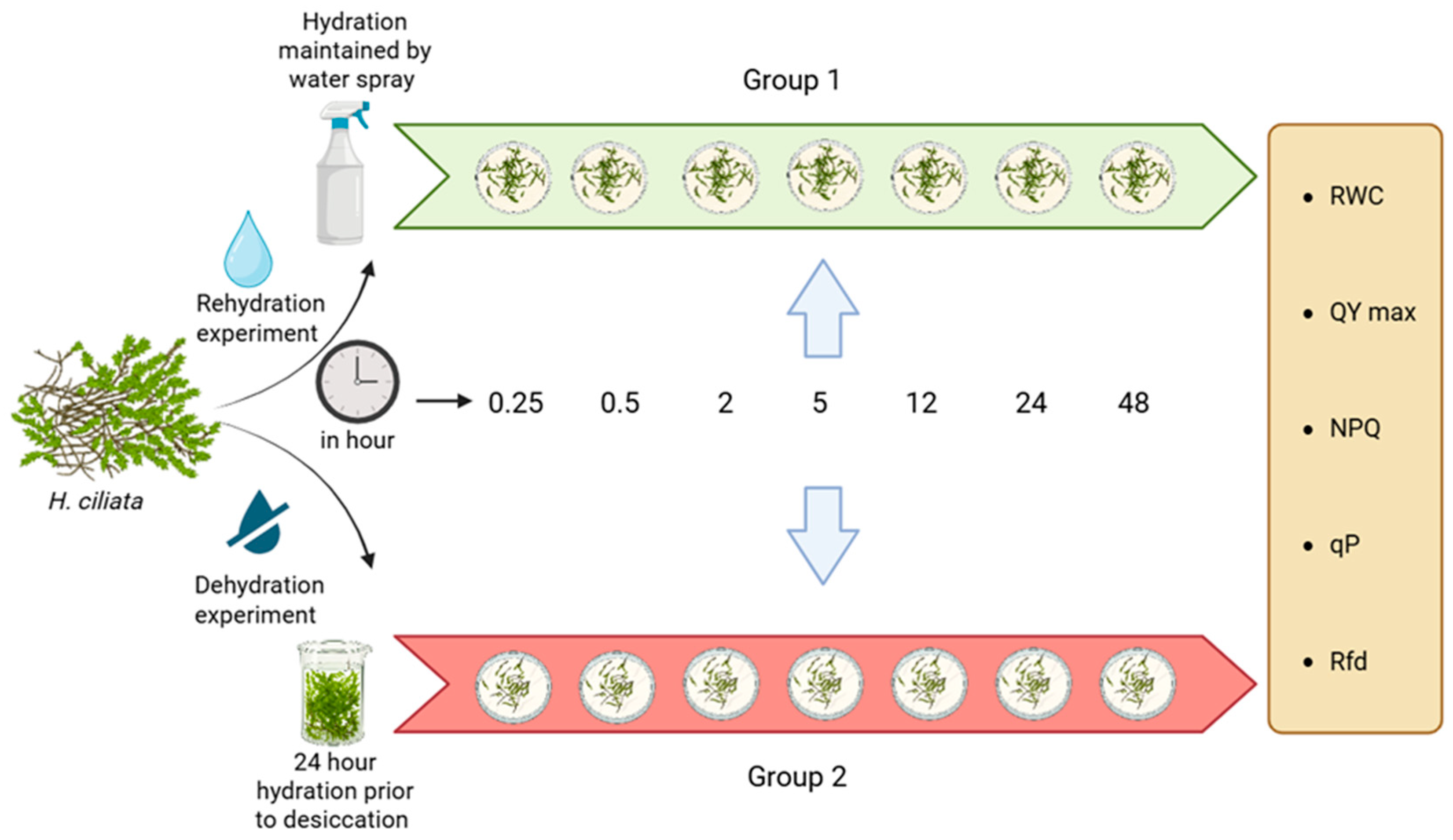

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of Samples

Experimental Design

4.2. Relative Water Content

4.3. Chlorophyll Fluorescence

- (A)

- Maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (QY max.) = Fv/Fm (where Fv = Fm − F0, F0 represents the ground fluorescence in the dark-adapted state and Fm represents the maximum fluorescence during a saturating radiation pulse in the dark-adapted state).

- (B)

- Photochemical quenching (qP).

- (C)

- Non-photochemical quenching (NPQ).

- (D)

- Fluorescence decline ratio (Rfd) = Fp/Ft (where Fp represents the fluorescence peak and Ft represents the steady-state fluorescence in the dark-adapted state).

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, H.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, C.; Xie, T.; Zheng, T.; Yu, C. Assessing the vitality status of plants: Using the correlation between stem water content and external environmental stress. Forests 2022, 18, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.U.; Adair, E.C.; Cardinale, B.J.; Byrnes, J.E.; Hungate, B.A.; Matulich, K.L.; Gonzalez, A.; Duffy, J.E.; Gamfeldt, L.; O’Connor, M.I. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature 2012, 486, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; He, K.S.; Hyvönen, J. Will bryophytes survive in a warming world? Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016, 19, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Sarkar, S.; Das, S.; Dutta, S.; Roy Choudhury, M.; Giri, A.; Bera, B.; Bag, K.; Mukherjee, B.; Banerjee, K.; et al. Water scarcity: A global hindrance to sustainable development and agricultural production—A critical review of the impacts and adaptation strategies. Camb. Prism. Water 2025, 3, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/05/drought-2050-un-report-climate-change/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Ciriaco da Silva, E.; Bandeira de Albuquerque, M.; Dias de Azevedo Neto, A.; Dias da Silva Junior, C. Drought and its consequences to plants—From individual to ecosystem. In Responses of Organisms to Water Stress; Akinci, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; pp. 17–47. ISBN 978-953-51-5346-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmgren, M.; Shabala, S. Adapting crops for climate change: Regaining lost abiotic stress tolerance in crops. Front. Sci. 2024, 2, 1416023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuba, Z.; Slack, N.G.; Stark, L.R. The Ecological Value of Bryophytes as Indicators of Climate Change. In Bryophyte Ecology and Climate Change; Tuba, Z., Slack, N.G., Stark, L.R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M.C.; Tuba, Z. Poikilohydry and homoihydry: Antithesis or spectrum of possibilities? New Phytol. 2002, 156, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, J.W.; Bokhorst, S.; Zielke, M.; Callaghan, T.V.; Bowles, F.W.; Phoenix, G.K. Contrasting sensitivity to extreme winter warming events of dominant sub-Arctic heathland bryophyte and lichen species. J. Ecol. 2011, 99, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, T.; Michelsen, O.; Graae, B.J.; Kyrkjeeide, M.O.; Holien, H.; Hassel, K.; Lindmo, S.; Kapás, R.E.; De Frenne, P. Impact of climate change on alpine vegetation of mountain summits in Norway. Ecol. Res. 2017, 32, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Božović, D.P.; Routray, D.; Backor, M.; Sabovljević, M.S.; Goga, M. An insight into drought resilience in three cohabiting mosses. Egypt. J. Bot. 2025, 65, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belnap, J.; Büdel, B.; Lange, O.L. Biological soil crusts: Characteristics and distribution. In Biological Soil Crusts: Structure, Function, and Management; Belnap, J., Lange, O.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Elbert, W.; Weber, B.; Burrows, S.; Steinkamp, J.; Büdel, B.; Andreae, M.O.; Pöschl, U. Contribution of cryptogamic covers to the global cycles of carbon and nitrogen. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Sánchez, J.Á.; Mark, K.; Souza, J.P.S.; Niinemets, Ü. Desiccation–rehydration measurements in bryophytes: Current status and future insights. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 4338–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligrone, R.; Duckett, J.G.; Renzaglia, K.S. Conducting tissues and phyletic relationships of bryophytes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 355, 795–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilks, T.; Proctor, M. Photosynthesis, respiration and water content in bryophytes. New Phytol. 1979, 82, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M. Physiological ecology: Water relations, light and temperature responses, carbon balance. In Bryophyte Ecology; Smith, A.J.E., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 333–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui-Lazo, J.; Wilson, M.; Mishler, B.D. The dynamics of external water conduction in the dryland moss Syntrichia. AoB Plants 2023, 15, plad025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitt, D.H.; Crandall-Stotler, B.; Wood, A. Bryophytes: Survival in a dry world through tolerance and avoidance. In Plant Ecology and Evolution in Harsh Environments; Rajakaruna, N., Kricsfalusy, V., Tobe, H., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 267–295. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Bai, W.; Yang, Q.; Yin, Z.; Zhao, B.; Kuang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D. The extremotolerant desert moss Syntrichia caninervis is a promising pioneer plant for colonizing extraterrestrial environments. Innovation 2024, 5, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, U.; Singh, H.; Kumar, D.; Soni, V. Rehydratation induces quick recovery of photosynthesis in desiccation tolerant moss Semibarbula orientalis. J. Plant Sci. Res. 2019, 35, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhindsa, R.; Matowe, W. Drought tolerance in two mosses: Correlated with enzymatic defence against lipid peroxidation. J. Exp. Bot. 1981, 32, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Y.; Lei, C.Y.; Jin, J.H.; Guan, Y.Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.S.; Liu, W.Q. Physiological responses of two moss species to the combined stress of water deficit and elevated N deposition (II): Carbon and nitrogen metabolism. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 7596–7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramyasheree, C.; Banupriya, T.G.; Yathisha, N.S.; Sharathchandra, R.G. Desiccation tolerance in the moss Hyophyla propagulifera: Coordinated physiological and biochemical responses during dessication and recovery. Ann. Biol. 2021, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, C.; Liu, T.; Zhang, X. Influence of drought stress and rehydration on moisture and photosynthetic physiological changes in three Epilithic Moss species in areas of karst rocky desertification. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 4944012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M.C.F.; Oliver, M.J.; Wood, A.J.; Alpert, P.; Stark, L.R.; Cleavitt, N.L.; Mishler, B.D. Desiccation-tolerance in bryophytes: A review. Bryologist 2007, 110, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ekwealor, J.T.B.; Mishler, B.D.; Silva, A.T.; Yu, L.; Jones, A.K.; Nelson, A.D.L.; Oliver, M.J. Syntrichia ruralis: Emerging model moss genome reveals a conserved and previously unknown regulator of desiccation in flowering plants. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zhang, Y.M.; Downing, A.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C. Membrane stability of the desert moss Syntrichia caninervis Mitt. during desiccation and rehydration. J. Bryol. 2012, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuba, Z.; Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Csintalan, Z.; Nagy, Z.; Szente, K. Reconstitution of chlorophylls and photosynthetic CO2 assimilation upon rehydration of the desiccated poikilochlorophyllous plant Xerophyta scabrida (Pax) Th. Dur. et Schinz. Planta 1994, 192, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, K.L.; Balsamo, R.A.; Espinoza, C.; Oliver, M.J. Desiccation sensitivity and tolerance in the moss Physcomitrella patens: Assessing limits and damage. Plant Growth Regul. 2010, 62, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebel, A.; Staniaszek-Kik, M.; Rosadzinski, S.; Wierzgon, M.; Fojcik, B.; Smoczyk, M.; Voncina, G. An unusual epiphytic habitat for Hedwigia ciliata (Bryophyta: Hedwigiaceae) in Poland (Central Europe). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2021, 90, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatova, E.A.; Kuznetsova, O.I.; Fedosov, V.E.; Ignatov, M.S. On the genus Hedwigia (Hedwigiaceae, Bryophyta) in Russia. Arctoa 2016, 25, 241–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.R.; Taniguchi, M.; Kooi, H.; Gurdak, J.J.; Allen, D.M.; Hiscock, K.M.; Treidel, H.; Aureli, A. Beneath the surface of global change: Impacts of climate change on groundwater. J. Hydrol. 2011, 405, 532–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-Z.; Ma, W.-Z.; Ignatov, M.S.; Ignatova, E.A.; Sulayman, M.; Wu, Y.-h.; Zhu, R.-L. A taxonomic revision of Hedwigia (Hedwigiaceae, Hedwigiales) in China. Phytotaxa 2024, 634, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, P.; Clymo, R. Profiles of water content and pore size in Sphagnum and peat, and their relation to peat bog ecology. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1982, 215, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkova, I.I.; Volkov, I.V.; Morozova, Y.A.; Nikitkin, V.A.; Vishnyakova, E.K.; Mironycheva-Tokareva, N.P. Water holding capacity of some Bryophyta species from tundra and north taiga of the West Siberia. Water 2023, 15, 2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbs, N.; Walter, D.; Barbosa, C.G.; Brill, S.; Alves, R.P.; Cerqueira, G.R.; de Oliveira Sá, M.; de Araújo, A.C.; de Oliveira, L.R.; Ditas, F. Microclimatic conditions and water content fluctuations experienced by epiphytic bryophytes in an Amazonian rain forest. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 5399–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz de Carvalho, R.; Maurício, A.; Pereira, M.F.; Marques da Silva, J.; Branquinho, C. All for one: The role of colony morphology in bryophyte desiccation tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Marín, B.; Kranner, I.; Sebastián, M.S.; Artetxe, U.; Laza, J.M.; Vilas, J.L.; Pritchard, H.W.; Nadajaran, J.; Míguez, F.; Becerril, J.M. Evidence for the absence of enzymatic reactions in the glassy state. A case study of xanthophyll cycle pigments in the desiccation-tolerant moss Syntrichia ruralis. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3033–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrant, J.M.; Moore, J.P. Programming desiccation-tolerance: From plants to seeds to resurrection plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz de Carvalho, R.; Afonso do Paço, T.; Branquinho, C.; Marques da Silva, J. Using chlorophyll a fluorescence imaging to select desiccation-tolerant native moss species for water-sustainable green roofs. Water 2020, 12, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, J.D.; Bradford, K.J.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Nonogaki, H. Seeds: Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy, 3rd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.J.; Farrant, J.M.; Hilhorst, H.W.; Mundree, S.; Williams, B.; Bewley, J.D. Desiccation tolerance: Avoiding cellular damage during drying and rehydration. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 435–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruchika; Csintalan, Z.; Péli, E.R. Seasonality and small spatial-scale variation of chlorophyll a fluorescence in bryophyte Syntrichia ruralis [Hedw.] in semi-arid sandy grassland, Hungary. Plants 2020, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, M.; Beckett, R.P. Photosynthetic responses in the inducible mechanisms of desiccation tolerance of a liverwort and a moss. Act. Biol. Szeged. 2005, 49, 155–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, K.B.; Rosputinský, M.; Grieš, M.; Puhovkin, A. Photoprotective mechanisms activated in Antarctic moss Chorisodontium aciphyllum during desiccation. Czech Polar Rep. 2024, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuba, Z.; Csintalan, Z.; Badacsonyi, A.; Proctor, M.C. Chlorophyll fluorescence as an exploratory tool for ecophysiological studies on mosses and other small poikilohydric plants. J. Bryol. 1997, 19, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deltoro, V.I.; Calatayud, A.; Gimeno, C.; Barreno, E. Water relations, chlorophyll fluorescence, and membrane permeability during desiccation in bryophytes from xeric, mesic, and hydric environments. Can. J. Bot. 1998, 76, 1923–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyyak, N.; Terek, O.; Baik, O.; Sokhanchak, R. Photosynthetic activity and protective reactions of mosses in forest ecosystems of the Ukrainian Roztochia under changing ecological conditions. Stud. Biol. 2025, 19, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.J.; Tuba, Z.; Mishler, B.D. The evolution of vegetative desiccation tolerance in land plants. Plant Ecol. 2000, 151, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Yobi, A.; Koster, K.L.; He, Y.; Oliver, M.J. Desiccation tolerance in Physcomitrella patens: Rate of dehydratation and the involvement of endogenous abscisic acid (ABA). Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Meléndez, S.; Valadez-Hernández, E.; Delgadillo, C.; Luna-Guevara, M.L.; Martinez-Nunez, M.A.; Sanchez-Perez, M.; Martinez y Perez, J.L.; Arroyo-Becerra, A.; Cardenas, L.; Bibbins-Martinez, M.; et al. Pseudocrossidium replicatum (Taylor) R.H. Zander is a fully desiccation-tolerant moss that expresses an inducible molecular mechanism in response to severe abiotic stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 107, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Yang, P.F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.Z.; Hu, Y.; Chen, H.; Kuang, T.Y.; Pei, Z.M.; Shen, S.H.; He, Y.K. Exploring the mechanism of Physcomitrella patens desiccation tolerance through a proteomic strategy. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 1739–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz de Carvalho, R.; Bernardes da Silva, A.; Soares, R.; Almeida, A.M.; Coelho, A.V.; Marques da Silva, J.; Branquinho, C. Differential proteomics of dehydration and rehydration in bryophytes: Evidence towards a common desiccation tolerance mechanism. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1499–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, L.R.; Brinda, J.C.; Greenwood, J.L. Propagula and shoots of Syntrichia pagorum (Pottiaceae) exhibit different ecological strategies of desiccation tolerance. Bryologist 2016, 119, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, L.R.; Brinda, J.C.; Mcletchie, D.N.; Oliver, M.J. Extended periods of hydration do not elicit dehardening to desiccation tolerance in regeneration trials of the moss Syntrichia caninervis. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 173, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, M.; Qi, Q.; Yang, Q.; López-Pujol, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, D. Complete organelle genome of the desiccation-tolerant (DT) moss Tortula atrovirens and comparative analysis of the Pottiaceae family. Genes 2024, 15, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, L.R.; Dos Santos, W.L. Do spores of Tortula inermis (Brid.) Mont. deharden to desiccation tolerance during germination? Crypt. Bryol. 2025, 46, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goga, M.; Ručova, D.; Kolarcik, V.; Sabovljević, M.; Bačkor, M.; Lang, I. Usnic acid, as a biotic factor, changes the ploidy level in mosses. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 2781–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozovic, D.P.; Cosic, M.V.; Kolarcik, V.; Goga, M.; Varotto, C.; Li, M.; Sabovljevic, A.D.; Sabovljevic, M.S. Different genotypes of the rare and threatened moss Physcomitrium eurystomum (Funariaceae) exhibit different resilience to zinc and copper stress. Plants 2025, 14, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, L.R. Ecology of desiccation tolerance in bryophytes: A conceptual framework and methodology. Bryologist 2017, 120, 129–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozovic, D.; Li, M.; Sabovljevic, A.; Sabovljevic, M.; Varotto, C. Sex determination in bryophytes: Current state of the art. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 6939–6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozovic, D.; Vesovic, M.V.; Jadranin, B.Z.; Matic, N.A.; Sabovljevic, A.D.; Sabovljevic, M.S. Axenic cultivation of bryophytes: Cultivated species checklist. Compr. Plant Biol. 2025, 49, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabovljević, M.S.; Ćosić, M.V.; Jadranin, B.Z.; Pantović, J.P.; Giba, Z.S.; Vujičić, M.M.; Sabovljević, A.D. The Conservation Physiology of Bryophytes. Plants 2022, 11, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šinžar-Sekulić, J.B.; Sabovljević, M.S.; Stevanović, B.M. Comparison of desiccation tolerance among mosses from different habitats. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2005, 57, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; Lawson, T. Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: A guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3983–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 25 December 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, P.; Božović, D.P.; Routray, D.; Goga, M.; Bačkor, M.; Sabovljević, M.S. Hydration–Dehydration Dynamics in the Desiccation-Tolerant Moss Hedwigia ciliata. Plants 2025, 14, 3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243849

Singh P, Božović DP, Routray D, Goga M, Bačkor M, Sabovljević MS. Hydration–Dehydration Dynamics in the Desiccation-Tolerant Moss Hedwigia ciliata. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243849

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Pragya, Djordje P. Božović, Deepti Routray, Michal Goga, Martin Bačkor, and Marko S. Sabovljević. 2025. "Hydration–Dehydration Dynamics in the Desiccation-Tolerant Moss Hedwigia ciliata" Plants 14, no. 24: 3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243849

APA StyleSingh, P., Božović, D. P., Routray, D., Goga, M., Bačkor, M., & Sabovljević, M. S. (2025). Hydration–Dehydration Dynamics in the Desiccation-Tolerant Moss Hedwigia ciliata. Plants, 14(24), 3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243849