Identification and Fine-Mapping of a Novel Locus qSCL2.4 for Resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Sunflower (Helianthus annuus)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Growth Conditions

2.3. Pathogen Inoculation and Disease Assessment

2.4. Phenotypic Data Analyses

2.5. Genotyping

2.6. Linkage Mapping and QTL Analysis

2.7. Development of KASP Markers

2.8. RNA Isolation and qPCR Analysis

2.9. Detection of HaWRKY48 Gene Polymorphism in Sunflower Germplasm

3. Results

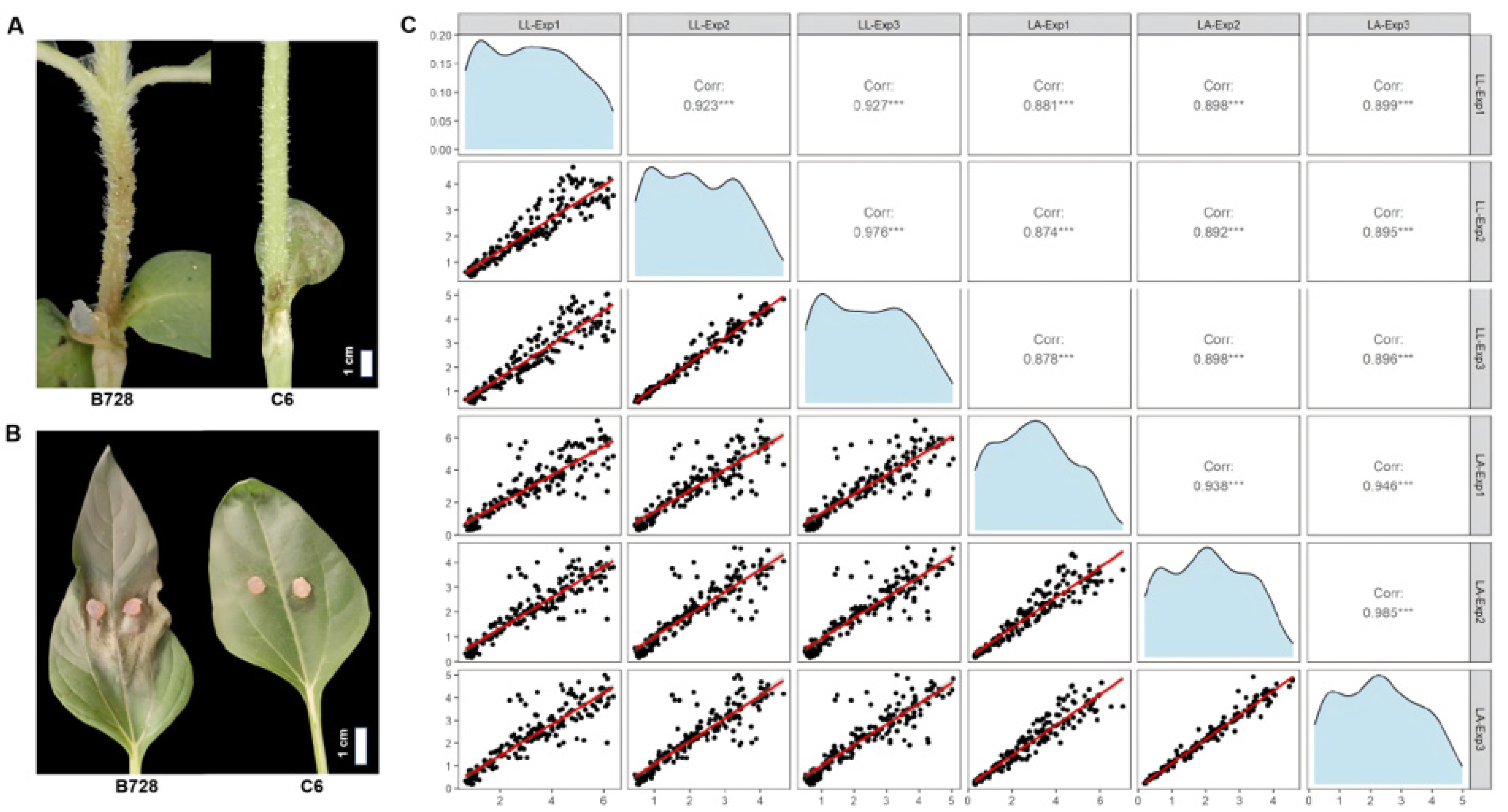

3.1. Phenotypic Variation in S. sclerotiorum Resistance Across the RIL Population

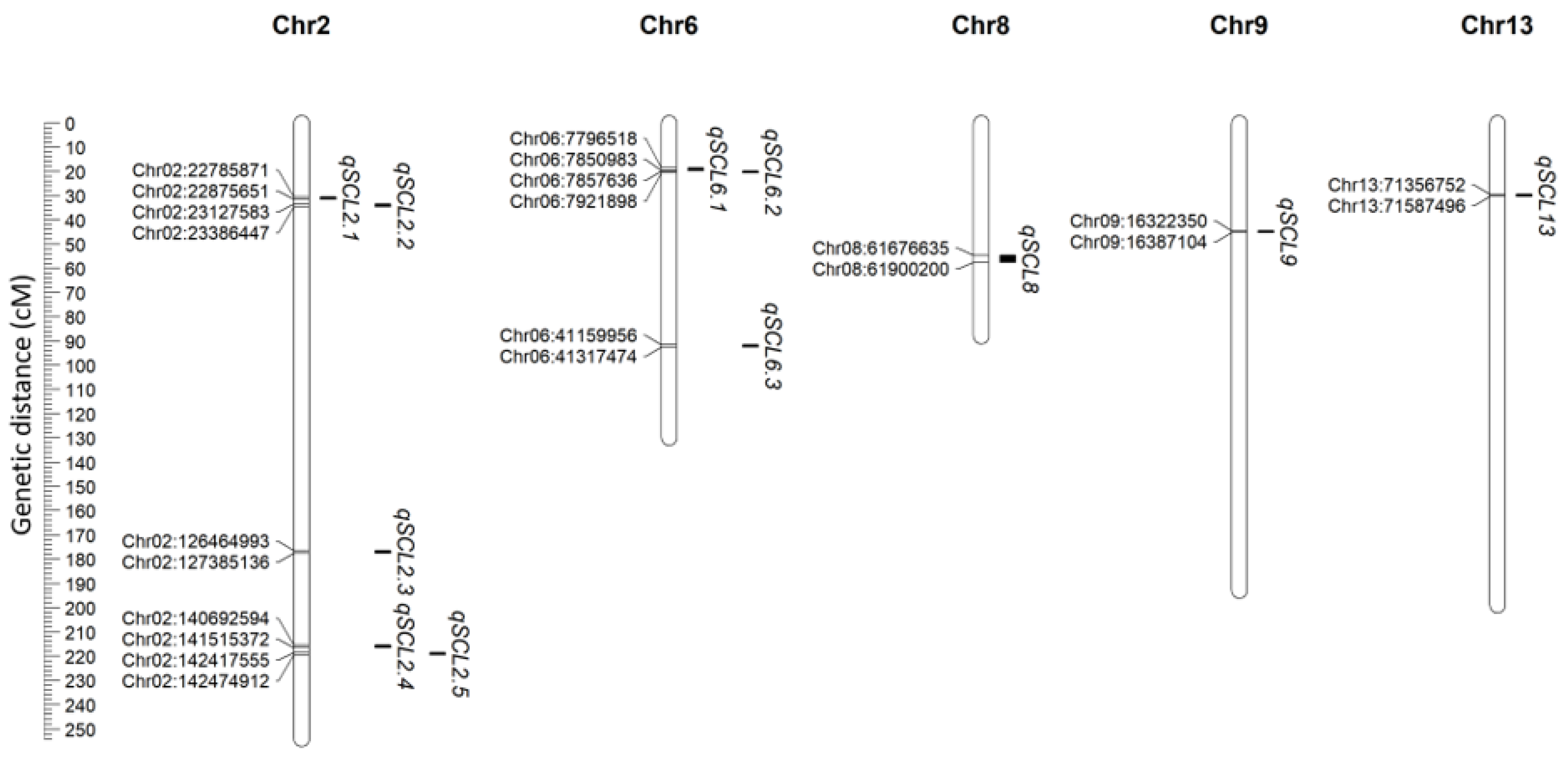

3.2. High-Density Linkage Mapping and Multi-Environment QTL Detection

3.3. Fine-Mapping of qSCL2.4 and Analyzing Candidate Genes

3.4. Natural Variation in HaWRKY48 Affects S. sclerotiorum Resistance in Sunflower

4. Discussion

4.1. Phenotypic of Sunflower Resistance to S. sclerotiorum

4.2. Identification of the Novel Locus qSCL2.4

4.3. Involvement of the WRKY Gene Family in Disease Resistance and Prediction of Candidate Genes

4.4. Excellent Allelic Variation in HaWRKY48

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adeleke, B.S.; Babalola, O.O. Oilseed crop sunflower (Helianthus annuus) as a source of food: Nutritional and health benefits. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 4666–4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, T.D.; Hoffman, D.D.; Diers, B.W.; Miller, J.F.; Steadman, J.R.; Hartman, G.L. Evaluation of soybean, dry bean, and sunflower for resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, L.E.; Bradley, C.A.; Henson, R.A.; Endres, G.J.; Hanson, B.K.; McKay, K.; Halvorson, M.; Porter, P.M.; Le Gare, D.G.; Lamey, H.A. Impact of Sclerotinia stem rot on yield of canola. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Peltier, A.J.; Meng, J.; Osborn, T.C.; Grau, C.R. Evaluation of Sclerotinia stem rot resistance in oilseed Brassica napus using a petiole inoculation technique under greenhouse conditions. Plant Dis. 2004, 88, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastien, M.; Sonah, H.; Belzile, F. Genome wide association mapping of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum resistance in soybean with a genotyping-by-sequencing approach. Plant Genome 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, V. Genetic variation for resistance to Sclerotinia head rot in sunflower inbred lines. Field Crops Res. 2002, 77, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestries, E.; Gentzbittel, L.; Tourvieille de Labrouhe, D.; Nicolas, P.; Vear, F. Analyses of quantitative trait loci associated with resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in sunflowers (Helianthus annuus L.) using molecular markers. Mol. Breed. 1998, 4, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bert, P.F.; Jouan, I.; Tourvieille de Labrouhe, D.; Serre, F.; Philippon, J.; Nicolas, P.; Vear, F. Comparative genetic analysis of quantitative traits in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). 2. Characterisation of QTL involved in developmental and agronomic traits. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 105, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micic, Z.; Hahn, V.; Bauer, E.; Schön, C.C.; Knapp, S.J.; Tang, S.; Melchinger, A.E. QTL mapping of Sclerotinia midstalk-rot resistance in sunflower. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 1474–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micic, Z.; Hahn, V.; Bauer, E.; Melchinger, A.E.; Knapp, S.J.; Tang, S.; Schön, C.C. Identification and validation of QTL for Sclerotinia midstalk rot resistance in sunflower by selective genotyping. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 111, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönicke, S.; Hahn, V.; Vogler, A.; Friedt, W. Quantitative trait loci analysis of resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in sunflower. Phytopathology 2005, 95, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Radi, S.A.; Vick, B.A.; Cai, X.; Tang, S.; Knapp, S.J.; Gulya, T.J.; Miller, J.F.; Hu, J. Identifying quantitative trait loci for resistance to Sclerotinia head rot in two USDA sunflower germplasms. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Amouzadeh, M.; Darvishzadeh, R.; Haddadi, P.; Abdollahi Mandoulakani, B. QTL mapping of partial resistance to basal stem rot in sunflower using recombinant inbred lines. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2013, 49, 330–341. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Zubrzycki, J.E.; Maringolo, C.A.; Filippi, C.V.; Quiróz, F.J.; Nishinakamasu, V.; Puebla, A.F.; Rienzo, J.A.D.; Escande, A.; Lia, V.V.; Heinz, R.A.; et al. Main and epistatic QTL analyses for Sclerotinia head rot resistance in sunflower. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 0189859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, Z.I.; Seiler, G.J.; Song, Q.; Ma, G.; Qi, L. SNP discovery and QTL mapping of Sclerotinia basal stalk rot resistance in sunflower using genotyping-by-sequencing. Plant Genome 2016, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talukder, Z.I.; Underwood, W.; Misar, C.G.; Seiler, G.J.; Cai, X.; Li, X.; Qi, L. A quantitative genetic study of sclerotinia head rot resistance introgressed from the wild perennial Helianthus maximiliani into cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talukder, Z.I.; Underwood, W.; Misar, C.G.; Seiler, G.J.; Cai, X.; Li, X.; Qi, L. Genomic insights into Sclerotinia basal stalk rot resistance introgressed from wild Helianthus praecox into cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 840954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, Z.I.; Underwood, W.; Misar, C.G.; Li, X.; Seiler, G.J.; Cai, X.; Qi, L. Genetic analysis of basal stalk rot resistance introgressed from wild Helianthus petiolaris into cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) using an advanced backcross population. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1278048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, Z.I.; Hulke, B.S.; Qi, L.; Scheffler, B.E.; Pegadaraju, V.; McPhee, K.; Gulya, T.J. Candidate gene association mapping of Sclerotinia stalk rot resistance in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) uncovers the importance of COI1 homologs. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusari, C.M.; Di Rienzo, J.A.; Troglia, C.; Nishinakamasu, V.; Moreno, M.V.; Maringolo, C.; Quiroz, F.; Álvarez, D.; Escande, A.; Hopp, E.H.; et al. Association mapping in sunflower for Sclerotinia head rot resistance. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, C.V.; Corro Molas, A.; Dominguez, M.; Colombo, D.; Heinz, N.; Troglia, C.; Maringolo, C.; Quiroz, F.; Alvarez, D.; Lia, V.; et al. Genome-wide association studies in sunflower: Towards Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Diaporthe/Phomopsis resistance breeding. Genes 2022, 13, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, C.V.; Zubrzycki, J.E.; Di Rienzo, J.A.; Quiroz, F.J.; Puebla, A.F.; Alvarez, D.; Maringolo, C.A.; Escande, A.R.; Hopp, H.E.; Paniego, N.B.; et al. Unveiling the genetic basis of Sclerotinia head rot resistance in sunflower. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Yi, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Song, D.; Sun, E.; Cui, L.; Liu, J.; Feng, L. Comparative transcriptome analysis in two contrasting genotypes for Sclerotinia sclerotiorum resistance in sunflower. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.C.; Sharma, P.; Rao, M.; Rai, P.K.; Gupta, A.K. Evaluation of non-injury inoculation technique for assessing Sclerotinia stem rot (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum) in oilseed Brassica. J. Microbiol. Methods 2020, 175, 105983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghai-Maroof, M.A.; Soliman, K.M.; Jorgensen, R.A.; Allard, R.W. Ribosomal DNA spacer-length polymorphisms in barley: Mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location, and population dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 8014–8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Hong, W.; Jiang, C.; Guan, N.; Ma, C.; Zeng, H.; et al. SLAF-seq: An efficient method of large-scale de novo SNP discovery and genotyping using high-throughput sequencing. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozich, J.J.; Westcott, S.L.; Baxter, N.T.; Highlander, S.K.; Schloss, P.D. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5112–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Stephens, M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 821–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J. QTL IciMapping: Integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in biparental populations. Crop J. 2015, 3, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.P.; Somssich, I.E. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 1648–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.H.; Anand, S.; Singh, B.; Bohra, A.; Joshi, R. WRKY transcription factors and plant defense responses: Latest discoveries and future prospects. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1071–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, T.; Gao, S.J. WRKY transcription factors in plant defense. Trends Genet. 2023, 39, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Wen, J.; Yi, B.; Shen, J.; Ma, C.; Fu, T.; Tu, J. Interactions of WRKY15 and WRKY33 transcription factors and their roles in the resistance of oilseed rape to Sclerotinia infection. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fang, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, K.; Li, G.; Gu, S.; Tan, X. Overexpression of BnWRKY33 in oilseed rape enhances resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2014, 15, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhuo, C.; Hu, K.; Li, X.; Wen, J.; Yi, B.; Shen, J.; Ma, C.; et al. Transcription factor WRKY28 curbs WRKY33-mediated resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Brassica napus. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 2757–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, D.H.; Lai, Z.B.; Zheng, Z.Y.; Vinod, K.M.; Fan, B.F.; Chen, Z.X. Stress-and pathogen-induced Arabidopsis WRKY48 is a transcriptional activator that represses plant basal defense. Mol. Plant 2008, 1, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radecka-Janusik, M.; Piechota, U.; Piaskowska, D.; Słowacki, P.; Bartosiak, S.; Czembor, P. Haplotype-based association mapping of genomic regions associated with Zymoseptoria tritici resistance using 217 diverse wheat genotypes. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Tarekegn, Z.T.; Jambuthenne, D.; Alahmad, S.; Periyannan, S.; Hickey, L.; Hayes, B. Stacking beneficial haplotypes from the Vavilov wheat collection to accelerate breeding for multiple disease resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.E.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Q.; Liu, S.; Zeng, Q.; Wu, J. Combined linkage and association mapping reveals two major QTL for stripe rust adult plant resistance in Shaanmai 155 and their haplotype variation in common wheat germplasm. Crop J. 2022, 10, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, Z.; Pironon, S.; Kantar, M.; Ramankutty, N.; Rieseberg, L. Shifts in the abiotic and biotic environment of cultivated sunflower under future climate change. Oil Seeds Fats Crops Lipids OCL 2019, 26, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ji, W.; Kang, Z. A necessary considering factor for breeding: Growth-defense tradeoff in plants. Stress Biol. 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Hao, Z.; Ning, Y.; He, Z. Revisiting growth–defence trade-offs and breeding strategies in crops. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Objective | Conditions (Year) | Plant Materials | Pathogen Inoculation | Disease Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QTL analysis | Exp1, Field (2022), Exp2, Climate chambers (2023), Exp3, Greenhouse (2022) | RILs and parents | Mycelial plugs | LL and LA, 3 dpi |

| Fine-mapping | Exp2, Climate chambers (2023) | BC1F3 and parents | Hyphal suspension | LA, 3 dpi |

| Haplotype analysis | Exp1, Field (2024), Exp2, Climate chambers (2024) | Germplasm | Mycelial plugs | LL and LA, 3 dpi |

| Trait | Condition | B728 | C6 | Mean | SE | Min | Max | H2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL (cm) | Exp1 | 7.27 | 0.77 | 3.20 | 1.72 | 0.61 | 7.15 | 0.94 |

| Exp2 | 5.05 | 0.68 | 2.20 | 1.16 | 0.42 | 4.96 | 0.95 | |

| Exp3 | 5.86 | 0.51 | 2.40 | 1.29 | 0.42 | 5.65 | 0.94 | |

| Average | 6.06 | 0.65 | 2.60 | 1.47 | 0.42 | 7.15 | 0.87 | |

| LA (cm2) | Exp1 | 7.41 | 0.31 | 3.01 | 1.71 | 0.28 | 7.32 | 0.96 |

| Exp2 | 5.52 | 0.21 | 2.08 | 1.18 | 0.16 | 5.42 | 0.95 | |

| Exp3 | 5.91 | 0.21 | 2.28 | 1.31 | 0.17 | 5.49 | 0.94 | |

| Average | 6.28 | 0.24 | 2.46 | 1.47 | 0.16 | 7.32 | 0.89 |

| QTL | Trait | Condition | Chr. | Left Marker | Right Marker | LOD | PVE (%) | Add |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qSCL2.1 | LL | Exp1 | 2 | Chr02:22785871 | Chr02:22875651 | 12.25 | 6.26 | 0.56 |

| qSCL2.2 | LL | Exp1 | 2 | Chr02:23127583 | Chr02:23386447 | 12.06 | 14.46 | 0.79 |

| LL | Mean | 2 | Chr02:23127583 | Chr02:23386447 | 11.45 | 14.48 | 0.60 | |

| qSCL2.3 | LL | Exp2 | 2 | Chr02:126464993 | Chr02:127385136 | 7.37 | 3.76 | 0.41 |

| LA | Exp2 | 2 | Chr02:126464993 | Chr02:127385136 | 7.04 | 10.11 | 0.45 | |

| LA | Exp3 | 2 | Chr02:126464993 | Chr02:127385136 | 6.61 | 10.53 | 0.48 | |

| LA | Mean | 2 | Chr02:126464993 | Chr02:127385136 | 10.35 | 6.32 | 0.44 | |

| qSCL2.4 | LL | Exp1 | 2 | Chr02:140692594 | Chr02:141515372 | 14.74 | 23.39 | 0.91 |

| LL | Exp2 | 2 | Chr02:140692594 | Chr02:141515372 | 37.92 | 28.15 | 1.11 | |

| LL | Exp3 | 2 | Chr02:140692594 | Chr02:141515372 | 16.23 | 25.71 | 0.71 | |

| LL | Mean | 2 | Chr02:140692594 | Chr02:141515372 | 14.85 | 25.42 | 0.73 | |

| LA | Exp1 | 2 | Chr02:140692594 | Chr02:141515372 | 19.26 | 25.62 | 1.03 | |

| LA | Exp2 | 2 | Chr02:140692594 | Chr02:141515372 | 37.68 | 32.86 | 1.00 | |

| LA | Exp3 | 2 | Chr02:140692594 | Chr02:141515372 | 40.39 | 30.22 | 1.23 | |

| LA | Mean | 2 | Chr02:140692594 | Chr02:141515372 | 19.29 | 27.31 | 0.82 | |

| qSCL2.5 | LL | Exp2 | 2 | Chr02:142417555 | Chr02:142474912 | 11.93 | 6.42 | −0.54 |

| LL | Exp3 | 2 | Chr02:142417555 | Chr02:142474912 | 12.07 | 7.53 | −0.48 | |

| LA | Exp2 | 2 | Chr02:142417555 | Chr02:142474912 | 13.14 | 6.81 | −0.59 | |

| qSCL6.1 | LA | Exp2 | 6 | Chr06:7796518 | Chr06:7850983 | 3.77 | 1.76 | 0.36 |

| LA | Exp3 | 6 | Chr06:7796518 | Chr06:7850983 | 3.01 | 3.98 | 0.36 | |

| LA | Mean | 6 | Chr06:7796518 | Chr06:7850983 | 2.91 | 4.20 | 0.39 | |

| qSCL6.2 | LA | Exp1 | 6 | Chr06:7857636 | Chr06:7921898 | 3.10 | 4.18 | 0.51 |

| qSCL6.3 | LL | Exp2 | 6 | Chr06:41159956 | Chr06:41317474 | 3.26 | 1.76 | 0.23 |

| LL | Exp3 | 6 | Chr06:41159956 | Chr06:41317474 | 3.55 | 1.59 | 0.28 | |

| qSCL8 | LL | Exp2 | 8 | Chr08:61676635 | Chr08:61900200 | 2.99 | 1.58 | −0.22 |

| qSCL9 | LL | Exp2 | 9 | Chr09:16322350 | Chr09:16387104 | 3.33 | 1.86 | 0.25 |

| LL | Mean | 9 | Chr09:16322350 | Chr09:16387104 | 2.62 | 3.03 | 0.28 | |

| qSCL13 | LL | Exp2 | 13 | Chr13:71356752 | Chr13:71587496 | 4.18 | 2.29 | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, M.; Wang, D.; Song, D.; Liu, X.; Yi, B.; Cao, Y.; Liu, J.; Feng, L. Identification and Fine-Mapping of a Novel Locus qSCL2.4 for Resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Sunflower (Helianthus annuus). Plants 2025, 14, 3826. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243826

Zhao M, Wang D, Song D, Liu X, Yi B, Cao Y, Liu J, Feng L. Identification and Fine-Mapping of a Novel Locus qSCL2.4 for Resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Sunflower (Helianthus annuus). Plants. 2025; 14(24):3826. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243826

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Mingzhu, Dexing Wang, Dianxiu Song, Xiaohong Liu, Bing Yi, Yuxuan Cao, Jingang Liu, and Liangshan Feng. 2025. "Identification and Fine-Mapping of a Novel Locus qSCL2.4 for Resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Sunflower (Helianthus annuus)" Plants 14, no. 24: 3826. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243826

APA StyleZhao, M., Wang, D., Song, D., Liu, X., Yi, B., Cao, Y., Liu, J., & Feng, L. (2025). Identification and Fine-Mapping of a Novel Locus qSCL2.4 for Resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Sunflower (Helianthus annuus). Plants, 14(24), 3826. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243826