Development and Characterization of Wheat-Thinopyrum elongatum 1B-1E Translocation Lines with Fusarium Head Blight Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

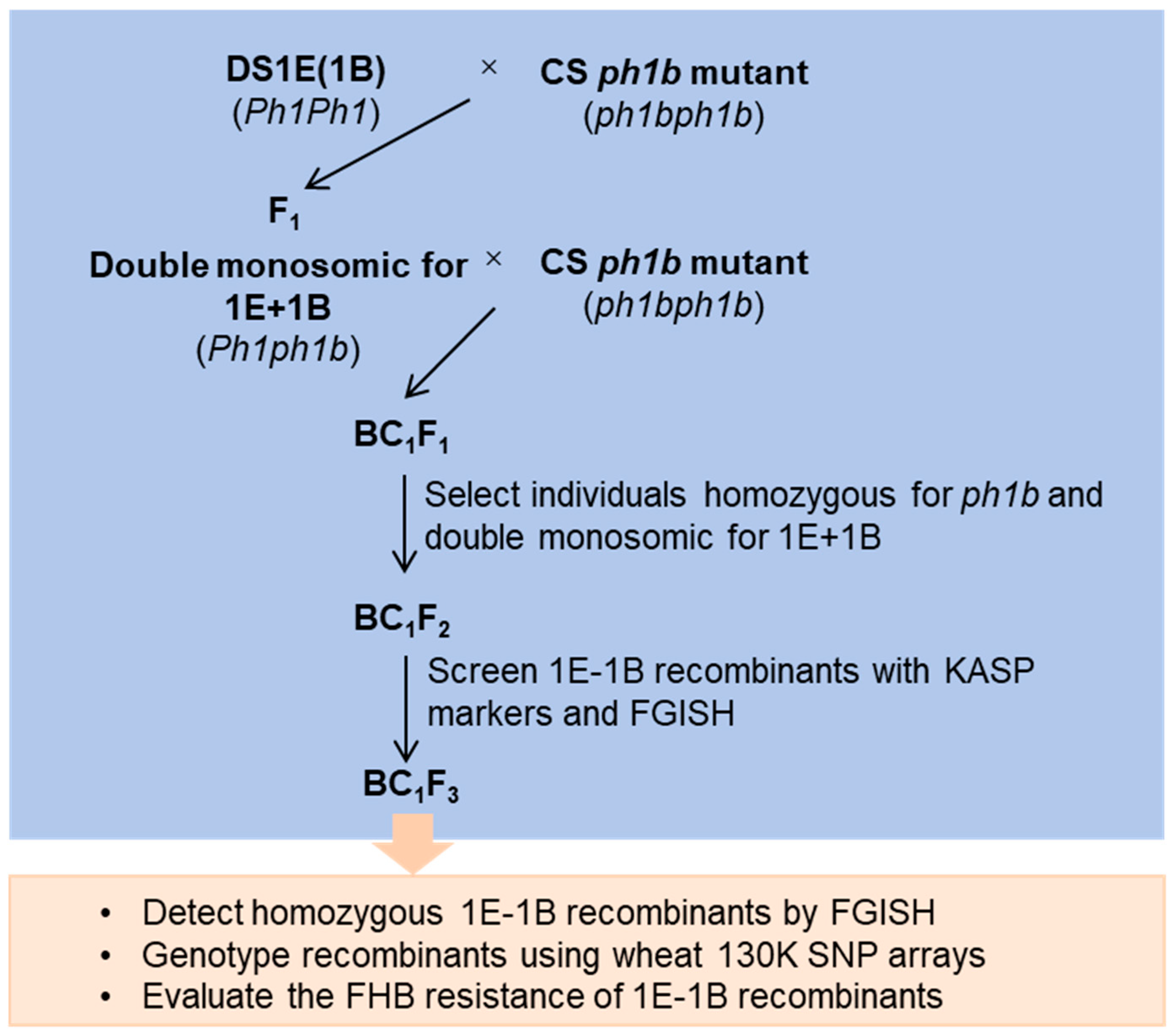

2.1. Construction of ph1b-Induced 1E/1B Homoeologous Recombination Population

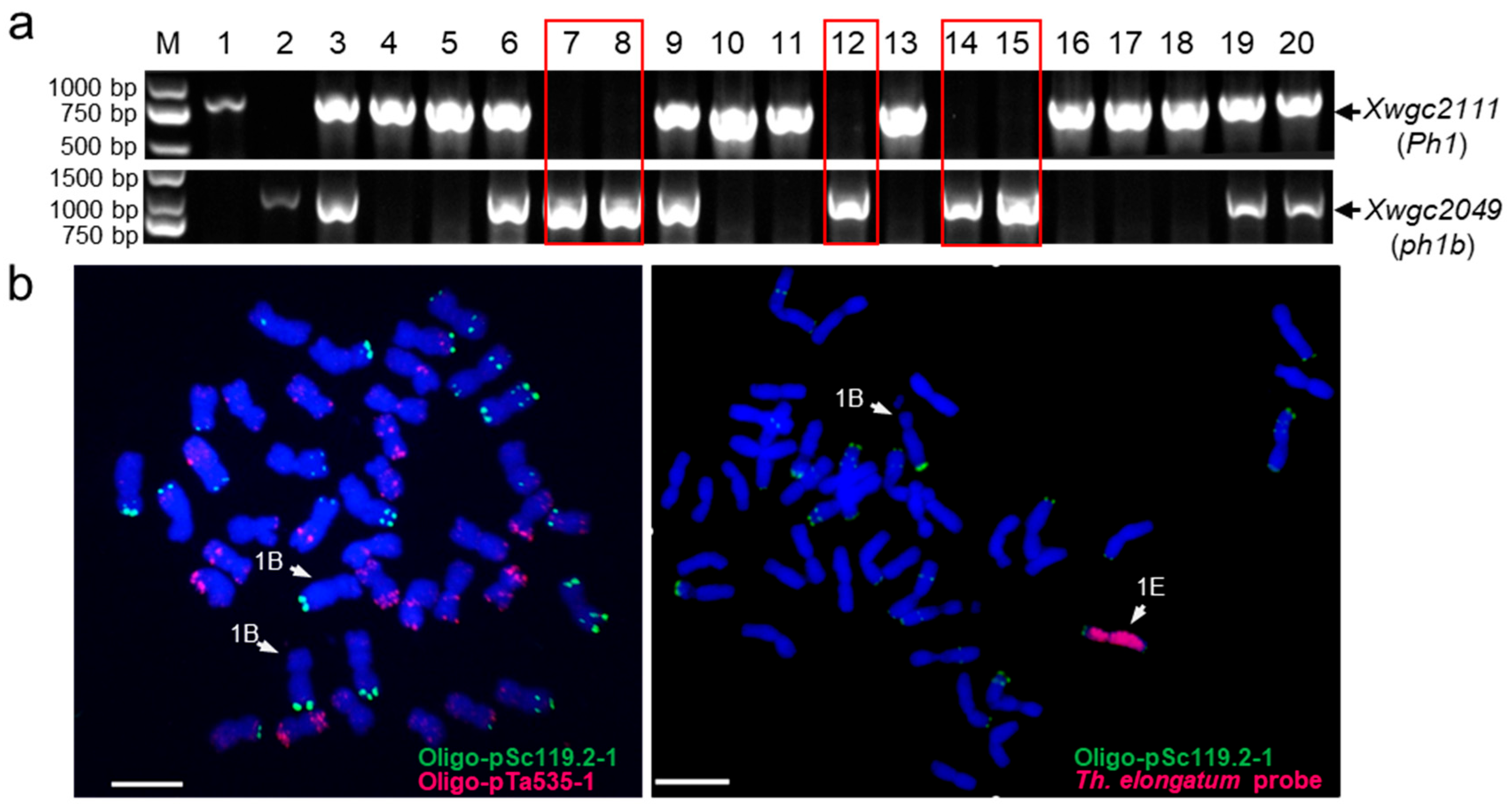

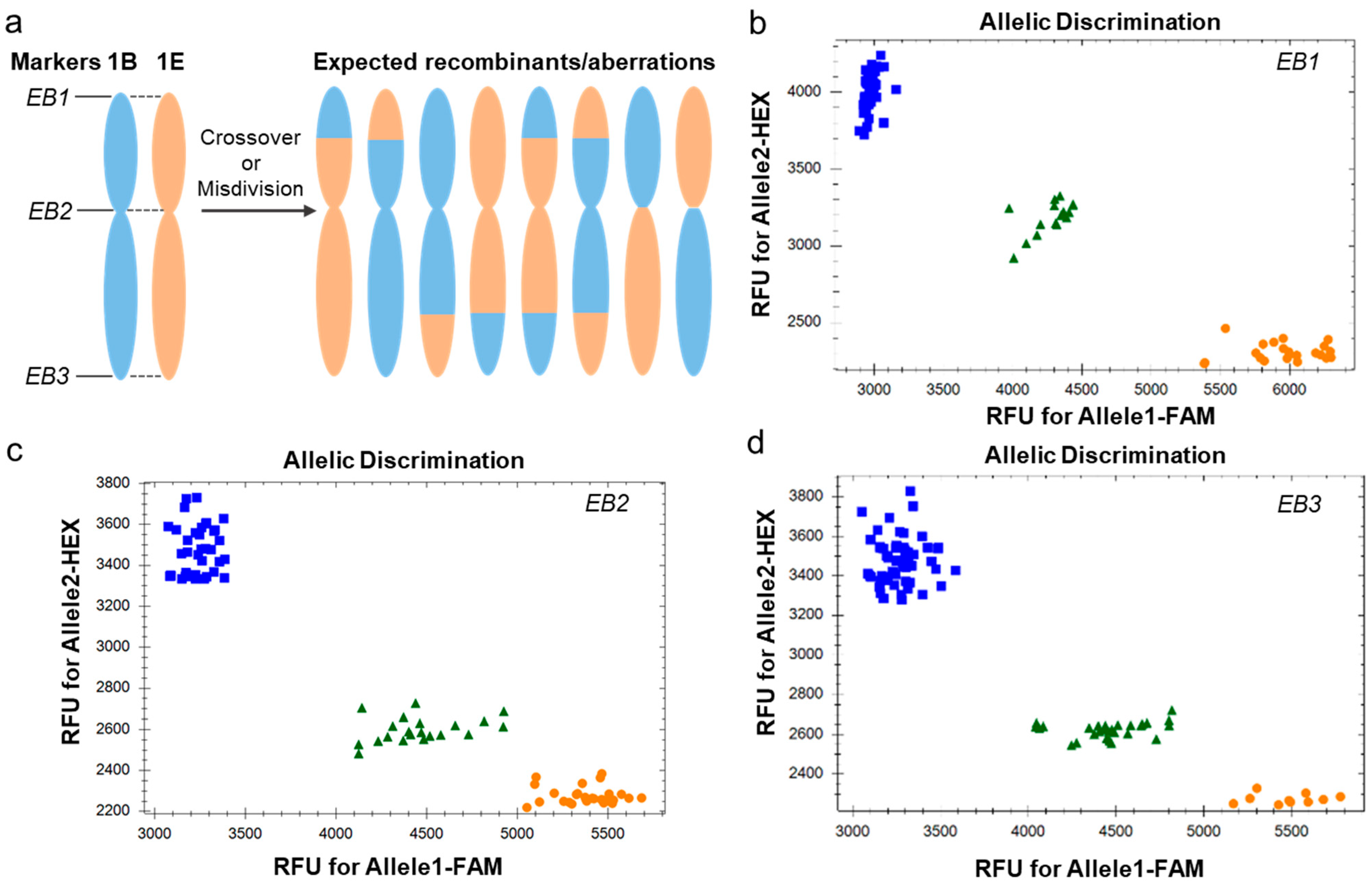

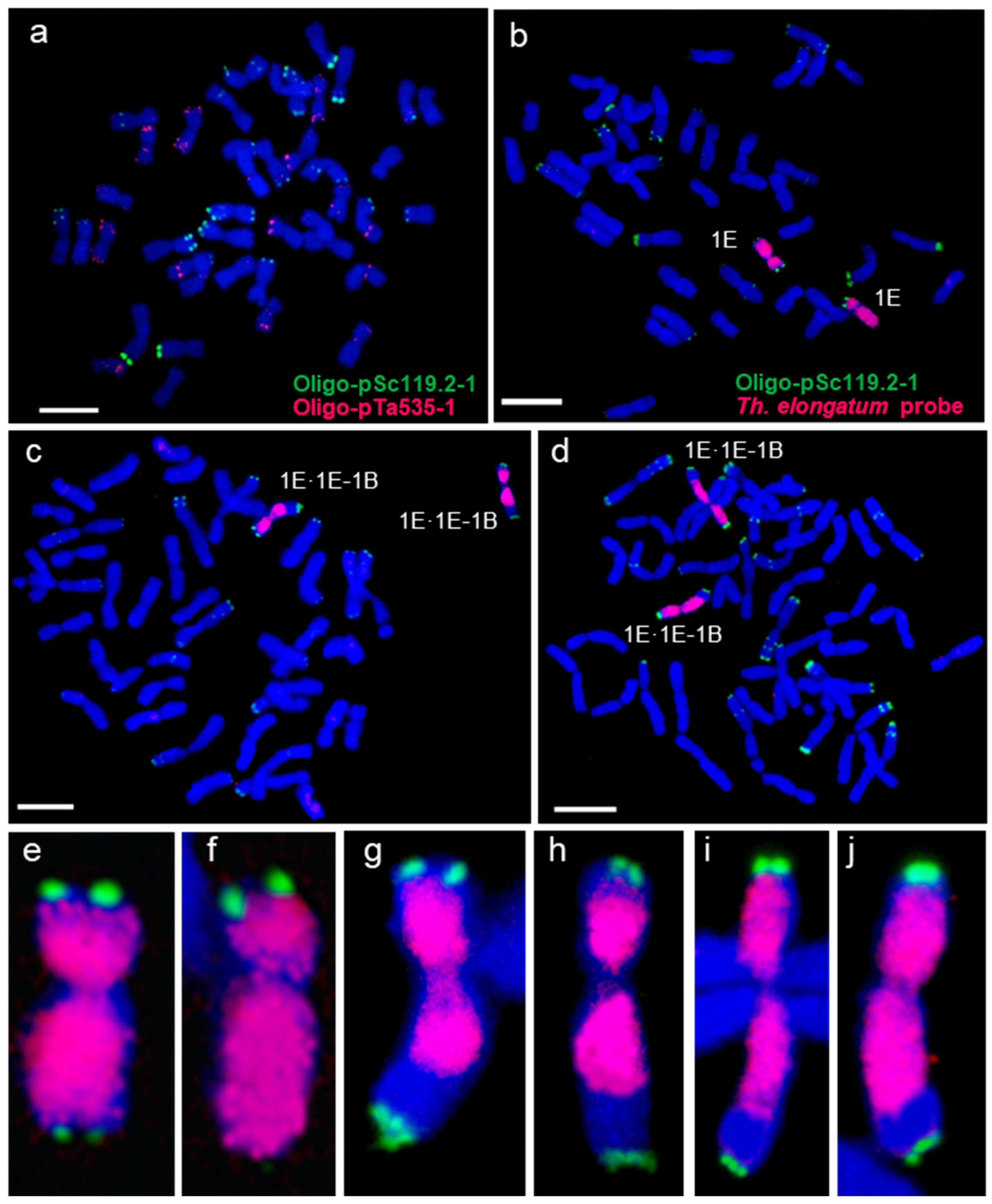

2.2. Screening and Verification of 1E-1B Recombinants by KASP Markers and GISH

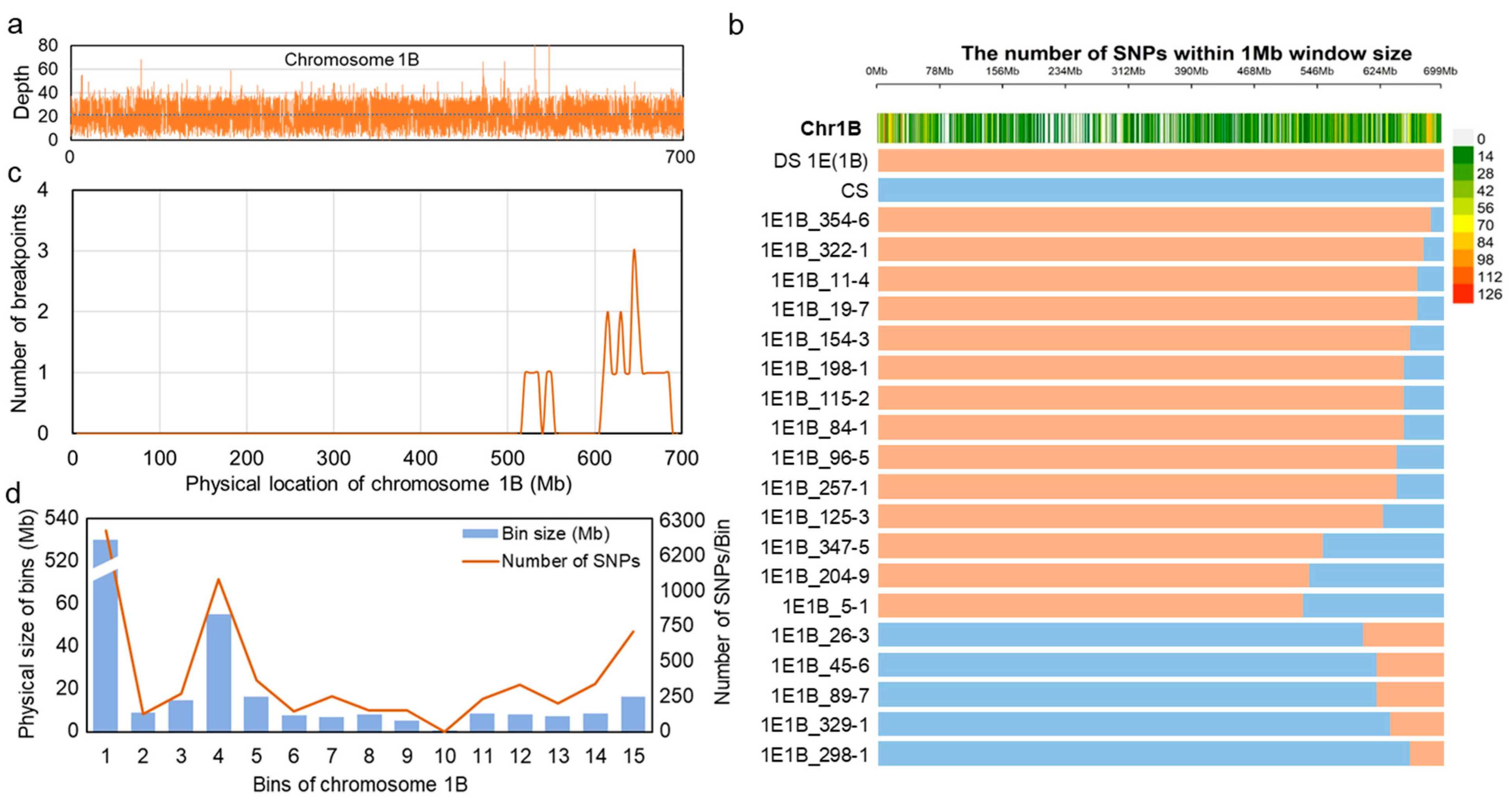

2.3. Homoeologous Recombination-Based Delineation and Physical Mapping of Wheat Chromosome 1B

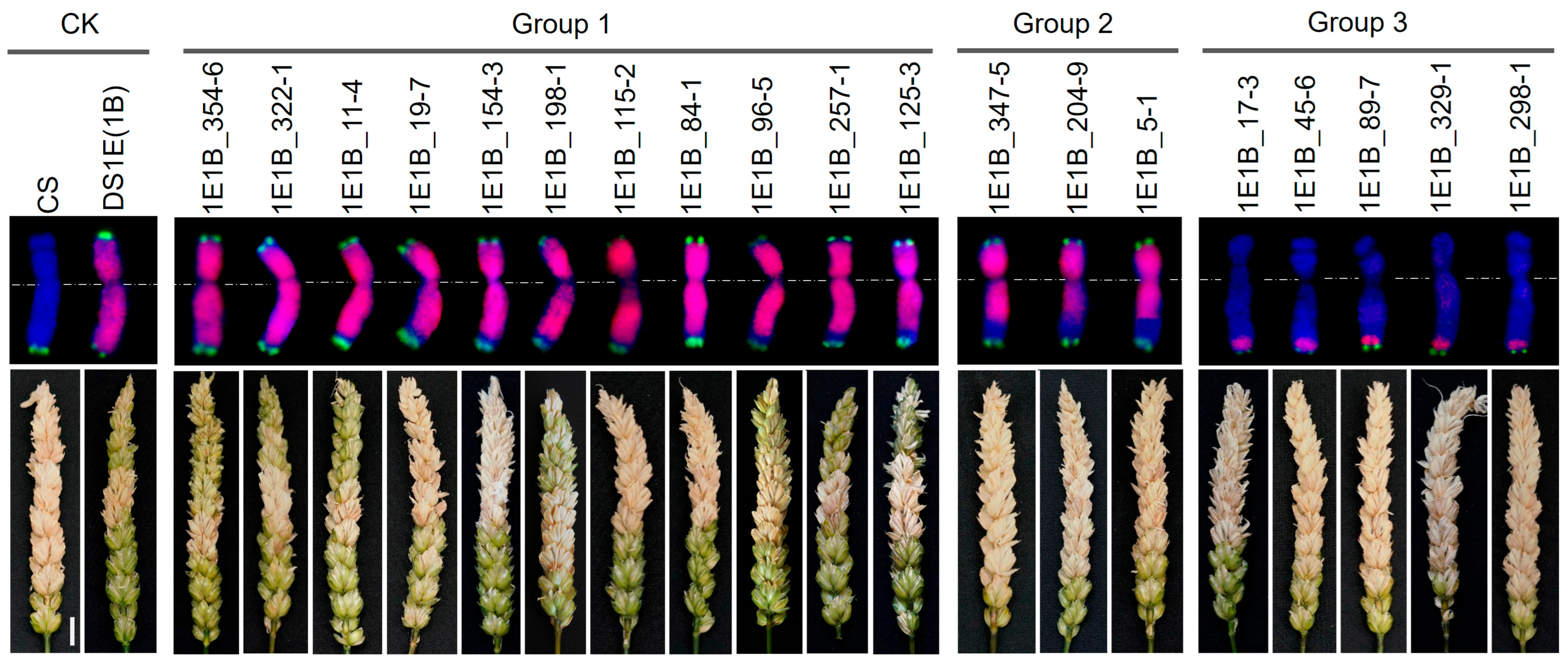

2.4. Evaluation of the Reaction of 1E-1B Recombinants to FHB

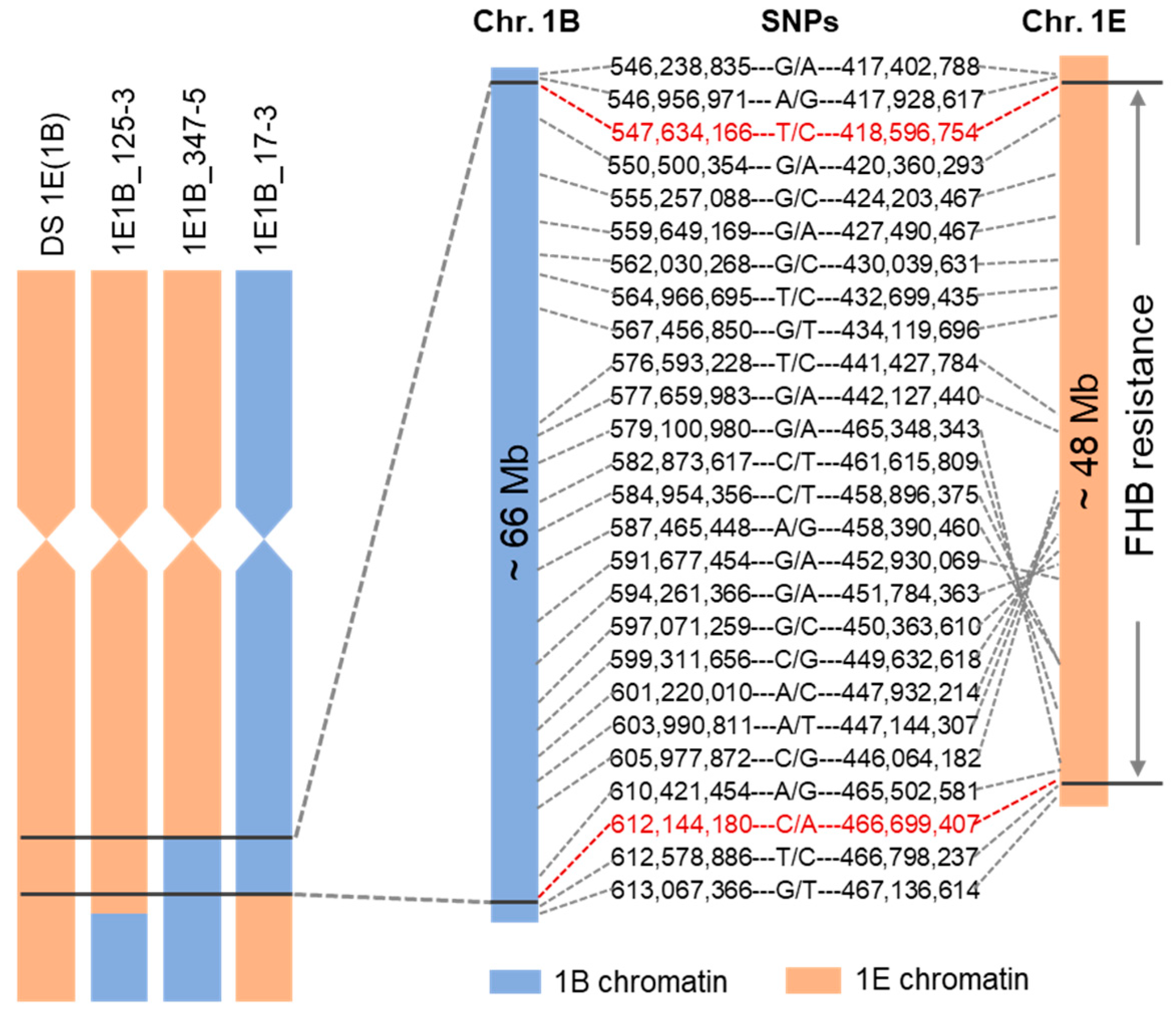

2.5. Molecular Mapping of the FHB Resistance Gene(s) on Th. elongatum 1E

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods Plant Materials

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Population Development

4.3. Cytogenetic Analysis

4.4. KASP Assay Analysis

4.5. Wheat 130K SNP Array and Bioinformatics Analysis

4.6. Physical Map Construction

4.7. FHB Disease Evaluation and Data Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McMullen, M.; Jones, R.; Gallenberg, D. Scab of wheat and barley: A re-emerging disease of devastating impact. Plant Dis. 1997, 81, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, G.; Shaner, G. Management and resistance in wheat and barley to fusarium head blight. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2004, 42, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hathout, A.; Aly, S. Biological detoxification of mycotoxins: A review. Ann. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trail, F. For blighted waves of grain: Fusarium graminearum in the postgenomics era. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, I.; Persson, P.; Friberg, H. Fusarium head blight from a microbiome perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 628373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerstmayr, M.; Steiner, B.; Buerstmayr, H. Breeding for Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat—Progress and challenges. Plant Breed. 2020, 139, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.Q.; Xie, Q.; Li, G.Q.; Jia, H.Y.; Zhou, J.Y.; Kong, Z.X.; Li, N.; Yuan, Y. Germplasms, genetics and genomics for better control of disastrous wheat Fusarium head blight. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 1541–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.S.; El-Basyoni, I.; Baenziger, P.S.; Singh, S.; Royo, C.; Ozbek, K.; Aktas, H.; Ozer, E.; Ozdemir, F.; Manickavelu, A.; et al. Exploiting genetic diversity from landraces in wheat breeding for adaptation to climate change. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3477–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, C.; Leroy, T.; Seidel, M.; Tondelli, A.; Duchemin, W.; Armisen, D.; Lang, D.; Bustos-Korts, D.; Goué, N.; Balfourier, F.; et al. Tracing the ancestry of modern bread wheats. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Ma, S.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, C.; Lu, Y.; Si, Y.; Tian, S.; Shi, X.; Liu, X.; Naeem, M.K. Whole-genome sequencing of diverse wheat accessions uncovers genetic changes during modern breeding in China and the United States. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 4199–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, X. Alien introgression and breeding of synthetic wheat. In Advances in Breeding Techniques for Cereal Crops; Ordon, F., Friedt, W., Eds.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 3–54. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.; Frei, M.; Zeibig, F.; Pantha, S.; Özkan, H.; Kilian, B.; Siddique, K.H.M. Back into the wild: Harnessing the power of wheat wild relatives for future crop and food security. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, eraf141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhao, Y. Harness the wild: Progress and perspectives in wheat genetic improvement. J. Genet. Genom. 2025; advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.L.; Pumphrey, M.O.; Friebe, B.; Chen, P.D.; Gill, B.S. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of alien introgressions with gene Fhb3 for resistance to Fusarium head blight disease of wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008, 117, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cainong, J.C.; Bockus, W.W.; Feng, Y.G.; Chen, P.D.; Qi, L.L.; Sehgal, S.K.; Danilova, T.V.; Koo, D.-H.; Friebe, B.; Gill, B.S. Chromosome engineering, mapping, and transferring of resistance to Fusarium head blight disease from Elymus tsukushiensis into wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Sun, S.; Ge, W.; Zhao, L.; Hou, B.; Wang, K.; Lyu, Z.; Chen, L.; Xu, S.; Guo, J.; et al. Horizontal gene transfer of Fhb7 from fungus underlies Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Science 2020, 368, eaba5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.; Chapman, V. Genetic control of the cytologically diploid behaviour of hexaploid wheat. Nature 1958, 182, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.; Chapman, V.; Kimber, G. Genetic control of chromosome pairing in intergeneric hybrids with wheat. Nature 1959, 185, 1244–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, E.R. An induced mutant with homoeologous pairing in common wheat. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 1977, 19, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello-Sampayo, T. Genetic regulation of meiotic chromosome pairing by chromosome 3D of Triticum aestivum. Nat. New Biol. 1971, 230, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.; Sharp, R.; Foote, T.; Bertin, I.; Wanous, M.; Reader, S.; Colas, I.; Moore, G. Molecular characterization of Ph1 as a major chromosome pairing locus in polyploid wheat. Nature 2006, 439, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Friebe, B.; Gill, B.S. Recent advances in alien gene transfer in wheat. Euphytica 1994, 73, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebe, B.; Jiang, J.; Raupp, W.J.; McIntosh, R.A.; Gill, B.S. Characterization of wheat–alien translocations conferring resistance to diseases and pests: Current status. Euphytica 1996, 91, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, R.; Nagarajan, R.; Bennypaul, H.; Sidhu, G.K.; Sidhu, G.; Rustgi, S.; Wettstein, D.; Gill, K.S. Silencing of a metaphase I-specific gene results in a phenotype similar to that of the Pairing homeologous 1 (Ph1) gene mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14187–14192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patokar, C.; Sepsi, A.; Schwarzacher, T.; Kishii, M.; Heslop-Harrison, J.S. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of novel wheat Thinopyrum bessarabicum recombinant lines carrying intercalary translocations. Chromosoma 2016, 125, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, M.; Martín, A.C.; Smedley, M.; Hayta, S.; Harwood, W.; Shaw, P.; Moore, G. Magnesium increases homoeologous crossover frequency during meiosis in ZIP4 (Ph1 gene) mutant wheat wild relative hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Klindworth, D.L.; Friesen, T.L.; Chao, S.; Jin, Y.; Cai, X.; Xu, S.S. Targeted introgression of a wheat stem rust resistance gene by DNA marker-assisted chromosome engineering. Genetics 2011, 187, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Danilova, T.V.; Rouse, M.N.; Bowden, R.L.; Friebe, B.; Gill, B.G. Development and characterization of a compensating wheat Thinopyrum intermedium Robertsonian translocation with Sr44 resistance to stem rust (Ug99). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Wang, H.; Xiao, J.; Bie, T.; Cheng, S.; Jia, Q.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, R.; Cao, A.; Chen, P.; et al. Induction of 4VS chromosome recombinants using the CS ph1b mutant and mapping of the wheat yellow mosaic virus resistance gene from Haynaldia villosa. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 2921–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Danilova, T.; Zhang, M.; Ren, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhong, S.; Dykes, L.; Fiedler, J.; Xu, S.; et al. Cytogenetic and genomic characterization of a novel tall wheatgrass-derived Fhb7 allele integrated into wheat B genome. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 4409–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jin, Y.; Li, W.; Kong, L.; Liu, X.; Xing, L.; Cao, A.; Zhang, R. Introgression of an adult-plant powdery mildew resistance gene Pm4VL from Dasypyrum villosum chromosome 4V into bread wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 20, 1401525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, M.; Chao, S.; Xu, S.; Cai, X. Meiotic homoeologous recombination-based mapping of wheat chromosome 2B and its homoeologues in Aegilops speltoides and Thinopyrum elongatum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 2381–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Klindworth, D.L.; Yu, G.; Friesen, T.L.; Chao, S.; Jin, Y.; Cai, X.; Ohm, J.-B.; Rasmussen, J.B.; Xu, S.S. Development and characterization of wheat lines carrying stem rust resistance gene Sr43 derived from Thinopyrum ponticum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 129, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danilova, T.V.; Friebe, B.; Gill, B.S. Development of a wheat single gene FISH map for analyzing homoeologous relationship and chromosomal rearrangements within the Triticeae. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, K.; Zhao, R.; Shi, M.; Xiao, J.; Yu, Z.; Jia, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, C.; Sun, H.; Cao, A.; et al. Dissection and cytological mapping of chromosome arm 4VS by the development of wheat-Haynaldia villosa structural aberration library. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 133, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Shi, Q.; Liu, Y.; Su, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Fu, S.; et al. Systemic development of wheat-Thinopyrum elongatum translocation lines and their deployment in wheat breeding for Fusarium head blight resistance. Plant J. 2023, 114, 1475–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wong, D.; Forrest, K.; Allen, A.; Huang, B.E.; Maccaferri, M.; Salvi, S.; Milner, S.G.; Cattivelli, L.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; et al. Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high density 90,000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfield, M.O.; Allen, A.M.; Burridge, A.J.; Barker, G.L.A.; Benbow, H.R.; Wilkinson, P.A.; Coghill, J.; Waterfall, C.; Davassi, A.; Scopes, G.; et al. High-density SNP genotyping array for hexaploid wheat and its secondary and tertiary gene pool. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.M.; Winfield, M.O.; Burridge, A.J.; Downie, R.C.; Benbow, H.R.; Barker, G.L.; Wilkinson, P.A.; Coghill, J.; Waterfall, C.; Davassi, A.; et al. Characterization of a Wheat Breeders’ Array suitable for high-throughput SNP genotyping of global accessions of hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chen, F. The wheat 660K SNP array demonstrates great potential for marker-assisted selection in polyploid wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burridge, A.J.; Winfield, M.; Przewieslik-Allen, A.; Edwards, K.J.; Siddique, I.; Barral-Arca, R.; Griffiths, S.; Cheng, S.; Huang, Z.; Feng, C.; et al. Development of a next generation SNP genotyping array for wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2235–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choulet, F.; Alberti, A.; Theil, S.; Glover, N.; Barbe, V.; Daron, J.; Pingault, L.; Sourdille, P.; Couloux, A.; Paux, E.; et al. Structural and functional partitioning of bread wheat chromosome 3B. Science 2014, 6194, 1249721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC). Shifting the limits in wheat research and breeding using a fully annotated reference genome. Science 2018, 361, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avni, R.; Nave, M.; Barad, O.; Baruch, K.; Twardziok, S.O.; Gundlach, H.; Hale, L.; Mascher, M.; Spannagl, M.; Wiebe, K.; et al. Wild emmer genome architecture and diversity elucidate wheat evolution and domestication. Science 2017, 357, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.C.; Gu, Y.Q.; Puiu, D.; Wang, H.; Twardziok, S.O.; Deal, K.R.; Huo, N.; Zhu, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Genome sequence of the progenitor of the wheat D genome Aegilops tauschii. Nature 2017, 551, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, H.Q.; Ma, B.; Shi, X.L.; Liu, H.; Dong, L.L.; Sun, H.; Cao, Y.H.; Gao, Q.; Zheng, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Genome sequence of the progenitor of wheat A subgenome Triticum urartu. Nature 2018, 557, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Dong, Z.; Ma, C.; Tian, X.; Qi, Z.; Wu, N.; Friebe, B.; Xiang, Z.; Xia, Q.; Liu, W.; et al. Physical mapping of stem rust resistance gene Sr52 from Dasypyrum villosum based on ph1b-induced homoeologous recombination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Gao, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, W.; Xu, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Fan, X.; et al. Development of wheat-tetraploid Thinopyrum elongatum 4EL small fragment translocation lines with stripe rust resistance gene Yr4EL. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiang, M.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Cheng, X.; Li, H.; Singh, R.P.; Bhavani, S.; Huang, S.; Zheng, W.; et al. Development and application of the GenoBaits Wheat SNP 16K array to accelerate wheat genetic research and breeding. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhar, P.P.; Peterson, T.S.; Xu, S.S. Cytogenetic and molecular characterization of a durum alien disomic addition line with enhanced tolerance to Fusarium head blight. Genome 2009, 52, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Lv, Z.; Qi, B.; Guo, X.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Han, F. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of wheat—Thinopyrum elongatum addition, substitution and translocation lines with a novel source of resistance to wheat Fusarium Head Blight. J. Genet. Genom. 2012, 39, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceoloni, C.; Forte, P.; Kuzmanović, L.; Tundo, S.; Moscetti, I.; De Vita, P.; Virili, M.E.; D’ovidio, R. Cytogenetic mapping of a major locus for resistance to Fusarium head blight and crown rot of wheat on Thinopyrum elongatum 7EL and its pyramiding with valuable genes from a Th. ponticum homoeologous arm onto bread wheat 7DL. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 2005–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, P.; Virili, M.E.; Kuzmanović, L.; Moscetti, I.; Gennaro, A.; D’Ovidio, R.; Ceoloni, C. A novel assembly of Thinopyrum ponticum genes into the durum wheat genome: Pyramiding Fusarium head blight resistance onto recombinant lines previously engineered for other beneficial traits from the same alien species. Mol. Breed. 2014, 34, 1701–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Y.; Cai, J.; Shen, X.; Zhou, T.; Xu, H.; Ohm, H.W.; Wang, H.; Li, A.; et al. High-density mapping of the major FHB resistance gene Fhb7 derived from Thinopyrum ponticum and its pyramiding with Fhb1 by marker-assisted selection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 2301–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedak, G.; Chi, D.; Wolfe, D.; Ouellet, T.; Cao, W.G.; Han, F.P.; Xue, A. Transfer of fusarium head blight resistance from Thinopyrum elongatum to bread wheat cultivar Chinese spring. Genome 2021, 64, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, D.; Xuan, Y.; He, Z.; Zhao, L.; Hao, Y.; Ge, W.; Xu, S.; Hou, B.; Wang, B.; et al. Elimination of the yellow pigment gene PSY-E2 tightly linked to the Fusarium head blight resistance gene Fhb7 from Thinopyrum ponticum. Crop J. 2023, 11, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Chen, P.D.; Xu, S.S.; Oliver, R.E.; Chen, X. Utilization of alien genes to enhance Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat: A review. Euphytica 2005, 142, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhar, P.P. Durum wheat genetic stocks involving chromosome 1E of diploid wheatgrass: Resistance to Fusarium head blight. Nucleus. 2014, 57, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H.W.; Christensen, J.J.; Christensen, J.D.; Platz-Christensen, J.J.; Schroeder, H. Factors affecting resistance of Wheat to scab caused by Gibberella zeae. Phytopathology 1963, 53, 831–838. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.D.; Young, J.C.; Sampson, D.R. Deoxynivalenol and Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Spring Cereals. J. Phytopathol. 1985, 113, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterházy, A. Types and components of resistance to Fusarium head blight of wheat. Plant Breed. 1995, 114, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.L.; Friebe, B.; Zhang, P.; Gill, B.S. Homoeologous recombination, chromosome engineering and crop improvement. Chromosome Res. 2007, 15, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Cao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Ma, G.; Chao, S.; Yan, C.; Xu, S.S.; Cai, X. Molecular cytogenetic and genomic analyses reveal new insights into the origin of the wheat B genome. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.; Sun, Q.; Chao, S.; Yan, C.; Xu, S.S.; Fiedler, J.; Cai, X. Partitioning and physical mapping of wheat chromosome 3B and its homoeologue 3E in Thinopyrum elongatum by inducing homoeologous recombination. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.; Sun, Q.; Yan, C.; Xu, S.S.; Fiedler, J.; Cai, X. Dissection and physical mapping of wheat chromosome 7B by inducing meiotic recombination with its homoeologues in Aegilops speltoides and Thinopyrum elongatum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 3455–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukaszewski, A.J.; Curtis, C.A. Physical distribution of recombination in B-genome chromosomes of tetraploid wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1993, 86, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erayman, M.; Sandhu, D.; Sidhu, D.; Dilbirligi, M.; Baenziger, P.S.; Gill, K.S. Demarcating the gene-rich regions of the wheat genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 3546–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saintenac, C.; Falque, M.; Martin, O.C.; Paux, E.; Feuillet, C.; Sourdille, P. Detailed recombination studies along chromosome 3B provide new insights on crossover distribution in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Genetics 2009, 181, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chao, S.; Xu, S.; Cai, X. Delimitation of wheat ph1b deletion and development of ph1b-specific DNA markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Jones, S.; Murray, T. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of Thinopyrum and wheat-Thinopyrum translocated chromosomes in a wheat Thinopyrum amphiploid. Chromosome Res. 1998, 6, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Fu, S. Oligonucleotides replacing the roles of repetitive sequences pAs1, pSc119.2, pTa-535, pTa71, CCS1, and pAWRC.1 for FISH analysis. Appl. Genet. 2014, 55, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Holme, J.; Anthony, J. SNP genotyping: The KASP assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1145, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhong, S.; Chao, S.; Gu, Y.Q.; Kianian, S.F.; Elias, E.; Cai, X.W. Toward a better understanding of the genomic region harboring Fusarium head blight resistance QTL Qfhs.ndsu-3AS in durum wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Markers | SNP Alleles | SNP Chromosome Location | SNP Reference Location (bp) a | Forward and Reverse Primers b | Polymorphism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EB1 | [G/A] | 1B | 1,518,466 | F1:[Tail1]-5′CAGAGGTTCGAGGAAGCT 3′ F2:[Tail2]-5′ACCTGATGAGTCAAGAGTG 3′ R:5′CACTCCCTCGTAGAACGCG 3′ | 1B-1E |

| EB2 | [A/G] | 1B | 383,971,145 | F1:[Tail1]-5′GAGGAAGTGTTTCAGCTGTG 3′ F2:[Tail2]-5′GGAAGTCAAAAGGCGGC 3′ R:5′CATGCTTCAACTTCTTCCAGCTC3′ | 1B-1E |

| EB3 | [A/T] | 1B | 697,751,963 | F1:[Tail1]-5′CACAAAGTAATCATCCAGTGT 3′ F2:[Tail2]-5′CAACACAAAGTAATCCAGTGA3′ R:5′AGCCAAGCTGTATGGCTACAG 3′ | 1B-1E |

| Lines | Translocated Chromosomes | Mean FHB Severity (%) * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 Fall | 2025 Spring | ||

| CS | 1B | 70.0 ± 6.4 b | 78.0 ± 7.5 a |

| DS1E(1B) | 1E | 25.8 ± 5.8 d | 42.8 ± 6.5 bcde |

| 1E1B_354-6 | 1E·1E-1B | 23.8 ± 6.2 d | 38.3 ± 6.3 de |

| 1E1B_322-1 | 1E·1E-1B | 26.2 ± 6.7 d | 41.0 ± 3.0 cde |

| 1E1B_11-4 | 1E·1E-1B | 29.3 ± 7.9 d | 36.0 ± 9.7 e |

| 1E1B_19-7 | 1E·1E-1B | 47.3 ± 4.5 c | 52.3 ± 7.2 b |

| 1E1B_154-3 | 1E·1E-1B | 47.0 ± 6.4 c | 46.8 ± 4.8 bcd |

| 1E1B_198-1 | 1E·1E-1B | 48.0 ± 6.8 c | 51.5 ± 7.1 b |

| 1E1B_115-2 | 1E·1E-1B | 50.0 ± 6.4 c | 53.5 ± 4.4 b |

| 1E1B_84-1 | 1E·1E-1B | 51.0 ± 6.7 c | 50.0 ± 6.7 bc |

| 1E1B_96-5 | 1E·1E-1B | 49.2 ± 7.7 c | 53.7 ± 5.5 b |

| 1E1B_257-1 | 1E·1E-1B | 30.3 ± 6.6 d | 45.2 ± 5.6 bcde |

| 1E1B_125-3 | 1E·1E-1B | 29.0 ± 5.3 d | 43.3 ± 5.6 bcde |

| 1E1B_347-5 | 1E·1E-1B | 72.5 ± 8.7 b | 78.8 ± 16.6 a |

| 1E1B_204-9 | 1E·1E-1B | 76.0 ± 12.7 ab | 73.3 ± 9.4 a |

| 1E1B_5-1 | 1E·1E-1B | 72.3 ± 10.2 b | 77.5 ± 13.2 a |

| 1E1B_17-3 | 1B·1B-1E | 83.2 ± 11.3 a | 75.8 ± 14.0 a |

| 1E1B_45-6 | 1B·1B-1E | 71.0 ± 15.3 b | 79.3 ± 11.8 a |

| 1E1B_89-7 | 1B·1B-1E | 72.5 ± 3.6 b | 75.5 ± 12.9 a |

| 1E1B_329-1 | 1B·1B-1E | 83.7 ± 11.6 a | 82.7 ± 11.8 a |

| 1E1B_298-1 | 1B·1B-1E | 76.0 ± 10.9 ab | 81.0 ± 6.4 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Guo, X.; He, H.; Wang, A.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, W. Development and Characterization of Wheat-Thinopyrum elongatum 1B-1E Translocation Lines with Fusarium Head Blight Resistance. Plants 2025, 14, 3805. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243805

Wang C, Liu Z, Wang X, Wang X, Guo X, He H, Wang A, Cao Y, Zhang W. Development and Characterization of Wheat-Thinopyrum elongatum 1B-1E Translocation Lines with Fusarium Head Blight Resistance. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3805. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243805

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Can, Zixuan Liu, Xingwen Wang, Xiaoni Wang, Xinyue Guo, Haitong He, Aiping Wang, Yaping Cao, and Wei Zhang. 2025. "Development and Characterization of Wheat-Thinopyrum elongatum 1B-1E Translocation Lines with Fusarium Head Blight Resistance" Plants 14, no. 24: 3805. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243805

APA StyleWang, C., Liu, Z., Wang, X., Wang, X., Guo, X., He, H., Wang, A., Cao, Y., & Zhang, W. (2025). Development and Characterization of Wheat-Thinopyrum elongatum 1B-1E Translocation Lines with Fusarium Head Blight Resistance. Plants, 14(24), 3805. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243805