Nutritional Status and Nitrogen Uptake Dynamics of Waxy-Type Winter Wheat Under Liquid Organic Fertilization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Variation in Soil Nitrogen Supply Due to the Application of Organic Fertilizers During Two Years of Winter Wheat Production

2.2. Nitrogen Use by Waxy Winter Wheat During the Period of Intensive Growth

2.3. Nitrogen Accumulation in Waxy Winter Wheat Yield and Nitrogen Uptake Intensity Throughout the Growing Season

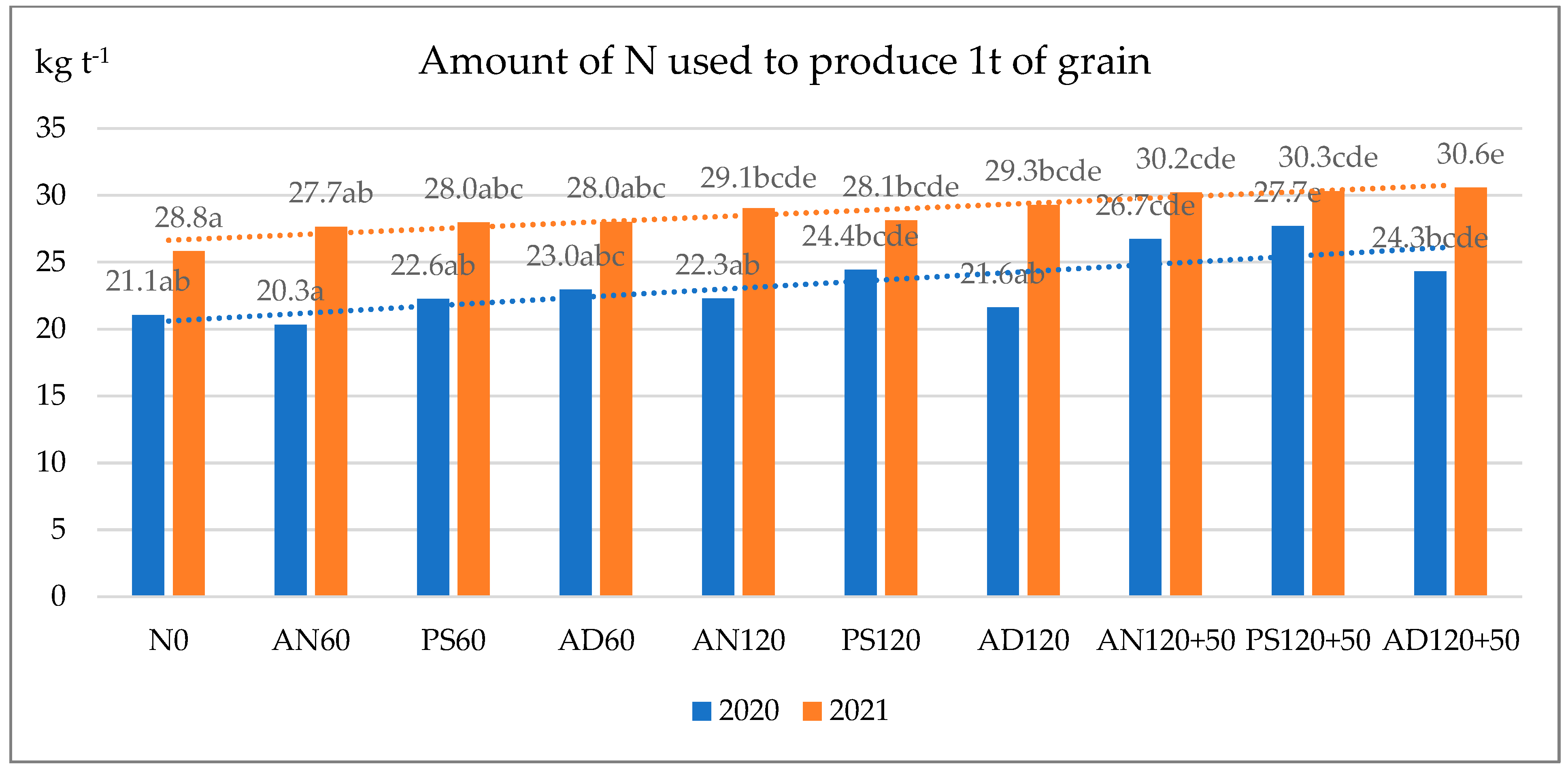

2.4. Productivity of Waxy Winter Wheat

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Site and Soil

4.2. Experimental Design and Details

4.3. Meteorological Conditions

4.4. Soil, Organic Fertilizers, and Plant Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McLennon, E.; Dari, B.; Jha, G.; Sihi, D.; Kankarla, V. Regenerative agriculture and integrative permaculture for sustainable and technology-driven global food production and security. Agron. J. 2021, 113, 4541–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atapattu, A.J.; Ranasinghe, C.S.; Nuwarapaksha, T.D.; Udumann, S.S.; Dissanayaka, N.S. Sustainable Agriculture and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In Emerging Technologies and Marketing Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture; Garwi, J., Masengu, R., Chiwaridzo, O., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badagliacca, G.; Testa, G.; La Malfa, S.G.; Cafaro, V.; Lo Presti, E.; Monti, M. Organic Fertilizers and Bio-Waste for Sustainable Soil Management to Support Crops and Control Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Mediterranean Agroecosystems: A Review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli, R.; Valboa, G.; Lagomarsino, A.; Fabiani, A.; Simoncini, S.; Zaghi, M.; Vignozzi, N. Recycling Biogas Digestate from Energy Crops: Effects on Soil Properties and Crop Productivity. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, J.; Chen, Z.; Park, Y. Potential Applications of Food-Waste-Based Anaerobic Digestate for Sustainable Crop Production Practice. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honcharuk, I.; Yemchyk, T.; Tokarchuk, D. Efficiency of Digestate from Biogas Plants for the Formation of Bio-Organic Technologies in Agriculture. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.J.; Jones, D.L.; Chadwick, D.R.; Williams, A.P. Repeated application of anaerobic digestate, undigested cattle slurry and inorganic fertilizer N: Impacts on pasture yield and quality. Grass Forage Sci. 2018, 73, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovičs, A.; Poiša, L. The effect of an innovative fertilizer of digestate and wood ash mixtures on winter garlic productivity. In Proceedings of the 14th International Scientific and Practical Conference, Rezekne, Latvia, 15–16 June 2023; Volume 1, pp. 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.J.; Rousk, J.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Jones, D.L.; Williams, A.P. Fungal and bacterial growth following the application of slurry and anaerobic digestate of livestock manure to temperate pasture soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2012, 48, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, C.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Clemente, R.; Bernal, M.P. Soil C and N mineralisation and agricultural value of the products of an anaerobic digestion system. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2013, 4, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonmatí, A.; Flotats, X. Pig Slurry Concentration by Vacuum Evaporation: Influence of Previous Mesophilic Anaerobic Digestion Process. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2003, 53, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkoa, R. Agricultural benefits and environmental risks of soil fertilization with anaerobic digestates: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.G.; Li, X.J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.G.; Cheng, B. Effect of microscale ZVI/magnetite on methane production and bioavailability of heavy metals during anaerobic digestion of diluted pig manure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 12328–12337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tong, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X. Biogas production and metal passivation analysis during anaerobic digestion of pig manure: Effects of a magnetic Fe3O4/FA composite supplement. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 4488–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graybosch, R.A. Waxy wheats: Origin, properties, and prospects. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 1998, 9, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.J.; Meldrum, A.; Wang, S.; Joyner, H.; Ganjyal, G.M. Waxy Wheat Flour as a Freeze-Thaw Stable Ingredient Through Rheological Studies. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 1281–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohm, J.-B.; Dykes, L.; Graybosch, R.A. Variation of protein molecular weight distribution parameters and their correlations with gluten and mixing characteristics for winter waxy wheat. Cereal Chem. 2019, 96, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesevičienė, J.; Gorash, A.; Liatukas, Ž.; Armonienė, R.; Ruzgas, V.; Statkevičiūtė, G.; Jaškūnė, K.; Brazauskas, G. Grain Yield Performance and Quality Characteristics of Waxy and Non-Waxy Winter Wheat Cultivars under High and Low-Input Farming Systems. Plants 2022, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zi, Y.; Ding, J.; Song, J.; Humphreys, G.; Peng, Y.; Li, C.; Zhu, X.; Guo, W. Grain Yield, Starch Content and Activities of Key Enzymes of Waxy and Non-waxy Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liatukas, Ž.; Ruzgas, V.; Gorash, A.; Cecevičienė, J.; Armonienė, R.; Statkevičiūtė, G.; Jaškūnė, K.; Brazauskas, G. Development of the new waxy winter wheat cultivars Eldija and Sarta. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2021, 57, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rroço, E.; Mengel, K. Nitrogen losses from entire plants of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum) from tillering to maturation. Eur. J. Agron. 2000, 13, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bang, T.C.; Husted, S.; Laursen, K.H.; Persson, D.P.; Schjoerring, J.K. The molecular–physiological functions of mineral macronutrients and their consequences for deficiency symptoms in plants. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2446–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Mohapatra, T. Interaction Between Macro- and Micro-Nutrients in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 665583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkesford, M.J.; Cakmak, I.; Coskun, D.; De Kok, L.J.; Lambers, H.; Schjoerring, J.K.; White, P.J. Chapter 6—Functions of macronutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Plants, 4th ed.; Rengel, Z., Cakmak, I., White, P.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 201–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobermann, A.; Ping, J.L.; Adamchuk, V.I.; Simbahan, G.C.; Ferguson, R.B. Classification of Crop Yield Variability in Irrigated Production Fields. Agron. J. 2003, 95, 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.H.; Teixeira, L.A.; Cantarella, H.; Rehm, G.W.; Grant, C.A.; Gearhart, M.M. Agronomic Effectiveness of Granular Nitrogen/Phosphorus Fertilizers Containing Elemental Sulfur with and without Ammonium Sulfate: A Review. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.K.; Bali, S.K. A Review of Methods to Improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Agriculture. Sustainability 2018, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, H.; Barraclough, P.B.; Weir, A.H. Utilization of mineral nitrogen in the subsoil by winter wheat. Z. Pflanzenernähr. Bodenkd. 1989, 152, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Anwar, S.; Shaobo, Y.; Gao, Z.; Sun, M.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Ren, A.; Yang, Z. Soil water consumption, water use efficiency and winter wheat production in response to nitrogen fertilizer and tillage. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, G.; Houssou, A.A.; Wu, H.; Cai, D.; Wu, X.; Gao, L.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Li, S. Seasonal Patterns of Soil Respiration and Related Soil Biochemical Properties under Nitrogen Addition in Winter Wheat Field. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbachová, G.; Růžek, P.; Kusá, H.; Vavera, R.; Káš, M. Winter Wheat Straw Decomposition under Different Nitrogen Fertilizers. Agriculture 2021, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.O.; Fugice, J.; Singh, U.; Lewis, T.D. Development of fertilizers for enhanced nitrogen use efficiency—Trends and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731, 139113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldren, R.P.; Flowerday, A.D. Growth Stages and Distribution of Dry Matter, N, P, and K in Winter Wheat. Agron. J. 1979, 71, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.C.; Di, H.J.; Moir, J.L. Nitrogen losses from the soil/plant system: A review. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2013, 162, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häfner, F.; Hartung, J.; Möller, K. Digestate Composition Affecting N Fertiliser Value and C Mineralisation. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 3445–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirel, B.; Tétu, T.; Lea, P.J.; Dubois, F. Improving Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Crops for Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1452–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Noor, H.; Noor, F.; Ding, P.; Sun, M.; Gao, Z. Effect of Soil Water and Nutrient Uptake on Nitrogen Use Efficiency, and Yield of Winter Wheat. Agronomy 2024, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, J.; Cao, P.; Hatfield, J.L. Are we getting better in using nitrogen?: Variations in nitrogen use efficiency of two cereal crops across the United States. Earths Future 2019, 7, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.V.; Raun, W.R. Nitrogen Response Index as a Guide to Fertilizer Management. J. Plant Nutr. 2003, 26, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubar, M.S.; Alshallash, K.S.; Asghar, M.A.; Feng, M.; Raza, A.; Wang, C.; Saleem, K.; Ullah, A.; Yang, W.; Kubar, K.A.; et al. Improving Winter Wheat Photosynthesis, Nitrogen Use Efficiency, and Yield by Optimizing Nitrogen Fertilization. Life 2022, 12, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, X.; Guo, W.; Feng, C. Effects of Climate Change on Wheat Yield and Nitrogen Losses per Unit of Yield in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River in China. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Owens, J.L.; Thomas, B.W.; Hao, X.; Coles, K.; Holzapfel, C.; Rahmani, E.; Karimi, R.; Gill, K.S.; Beres, B.L. Winter wheat responses to enhanced efficiency granular nitrogen fertilizer in the Canadian Prairies. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2023, 103, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekała, W. Digestate as a Source of Nutrients: Nitrogen and Its Fractions. Water 2022, 14, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Senbayram, M.; Blagodatsky, S.; Myachina, O.; Dittert, K.; Lin, X.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Kuzyakov, Y. Soil C and N availability determine the priming effect: Microbial N mining and stoichiometric decomposition theories. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 2356–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuland, G.; Sigurnjak, I.; Dekker, H.; Sleutel, S.; Meers, E. Assessment of the Carbon and Nitrogen Mineralisation of Digestates Elaborated from Distinct Feedstock Profiles. Agronomy 2022, 12, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; He, Z.; Zhu, T.; Zhao, F. Organic-C quality as a key driver of microbial nitrogen immobilization in soil: A meta-analysis. Geoderma 2021, 383, 114784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, K. Effects of anaerobic digestion on soil carbon and nitrogen turnover, N emissions, and soil biological activity. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1021–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, A.; Carter, M.S.; Jensen, E.S.; Hauggard-Nielsen, H.; Ambus, P. Effects of digestate from anaerobically digested cattle slurry and plant materials on soil microbial community and emission of CO2 and N2O. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2013, 63, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, M.; Stinner, W. Effects of different manuring systems with and without biogas digestion on soil mineral nitrogen content and on gaseous nitrogen losses (ammonia, nitrous oxides). Eur. J. Agron. 2009, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, B.; Sadet-Bourgeteau, S.; Cannavacciuolo, M.; Chauvin, C.; Flamin, C.; Haumont, A.; Jean-Baptiste, V.; Reibel, A.; Vrignaud, G.; Ranjard, L. Impact of biogas digestates on soil microbiota in agriculture: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 3265–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, D.; Cabassi, G.; Borrelli, L.; Geromel, G.; Bechini, L.; Degano, L.; Gallina, P.M. Nitrogen fertilizer replacement value of undigested liquid cattle manure and digestates. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 73, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, Z.; Feyisa, H. Effects of Nitrogen Rates and Time of Application on Yield of Maize: Rainfall Variability Influenced Time of N Application. Int. J. Agron. 2017, 2017, 1545280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, P.C.; Lory, J.A. Calibrating Corn Color from Aerial Photographs to Predict Sidedress Nitrogen Need. Agron. J. 2002, 94, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwary, A.; Williams, I.D.; Pant, D.C.; Kishore, V.V.N. Assessment and mitigation of the environmental burdens to air from land applied food-based digestate. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 203, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickenscheidt, T.; Freibauer, A.; Heinichen, J.; Augustin, J.; Drösler, M. Short-term effects of biogas digestate and cattle slurry application on greenhouse gas emissions affected by N availability from grasslands on drained fen peatlands and associated organic soils. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 6187–6207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, V.V.; Banerjee, P.; Verma, V.C.; Sukumaran, S.; Chandran, M.A.S.; Gopinath, K.A.; Venkatesh, G.; Yadav, S.K.; Singh, V.K.; Awasthi, N.K. Plant Nutrition: An Effective Way to Alleviate Abiotic Stress in Agricultural Crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melero, S.; Porras, J.C.R.; Herencia, J.F.; Madejon, E. Chemical and biochemical properties in a silty loam soil under conventional and organic management. Soil Tillage Res. 2006, 90, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlare, M.; Pell, M.; Svensson, K. Changes in soil chemical and microbiological properties during 4 years of application of various organic residues. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möller, K.; Stinner, W.; Deuker, A.; Leithold, G. Effects of different manuring systems with and without biogas digestion on nitrogen cycle and crop yield in mixed organic dairy farming systems. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2008, 82, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka-Czubaszek, A. Dynamics of Nitrogen Transformations in Soil Fertilized with Digestate from Agricultural Biogas Plant. J. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 20, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, C.; Orzi, V.; Carozzi, M.; Acutis, M.; Boccasile, G.; Lonati, S.; Tambone, F.; D’Imporzano, G.; Adani, F. Short-term experiments in using digestate products as substitutes for mineral (N) fertilizer: Agronomic performance, odours, and ammonia emission impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 547, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, F.; Bhogal, A.; Cardenas, L.; Chadwick, D.; Misselbrook, T.; Rollett, A.; Taylor, M.; Thorman, R.; Williams, J. Nitrogen losses to the environment following food-based digestate and compost applications to agricultural land. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 228, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangueiro, D.; Hjorth, M.; Gioelli, F. Acidification of animal slurry—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 149, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, A.R.; Carswell, A.M.; Shaw, R.; Hunt, J.; Saunders, K.; Cotton, J.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L.; Misselbrook, T.H. Advanced Processing of Food Waste Based Digestate for Mitigating Nitrogen Losses in a Winter Wheat Crop. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuccio, M.R.; Romeo, F.; Mallamaci, C.; Muscolo, A. Digestate Application on Two Different Soils: Agricultural Benefit and Risk. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 4341–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoraj, M.; Mironiuk, M.; Izydorczyk, G.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Szopa, D.; Moustakas, K.; Chojnacka, K. The challenges and perspectives for anaerobic digestion of animal waste and fertilizer application of the digestate. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraityte, D.; Ceseviciene, J.; Arlauskiene, A.; Slepetiene, A.; Skersiene, A.; Gecaite, V. Variation of Soil Nitrogen, Organic Carbon, and Waxy Wheat Yield Using Liquid Organic and Mineral Fertilizers. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mažvila, J.; Vaišvila, Z. Evaluation of Agricultural Crop Productivity Based on the Total Energy Amount. In Soil Productivity of Lithuania; Mažvila, J., Ed.; Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry: Akademija, (Kėdainiai District), Lithuania, 2011; pp. 105–107. (In Lithuanian) [Google Scholar]

- Tarakanovas, P.; Raudonius, S. Statistical Analysis of Agronomic Research Data Using Computer Programs ANOVA, STAT, SPLIT-PLOT from the Package SELEKCIJA and IRRISTAT; Lithuanian University of Agriculture: Akademija, (Kaunas District), Lithuania, 2003; p. 58. (In Lithuanian) [Google Scholar]

| Treatments | Sampling Periods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | |||||

| 1AV | 1IG | 1AH | 2AV | 2IG | 2AH | |

| N0 | 5.18 ± 0.08 | 9.46 ± 0.61 | 13.26 ± 0.43 | 4.11 ± 0.32 | 4.68 ± 0.63 | 2.38 ± 0.28 |

| Time × N rates | ||||||

| N60 | 5.13 cd | 11.33 f | 12.73 g | 4.57 bc | 6.14 de | 3.22 a |

| N120 | 5.13 cd | 11.79 e | 15.61 h | 4.65 bc | 6.73 e | 3.50 ab |

| N120 + 50 | 5.13 cd | 11.49 fg | 15.56 h | 4.53 c | 6.81 e | 6.47 e |

| Time × fertilizer | ||||||

| AN | 5.13 abc | 10.37 d | 14.16 efg | 4.26 a | 7.65 d | 4.53 a |

| PS | 5.13 abc | 10.93 d | 14.54 efg | 4.84 abc | 5.87 bc | 4.17 a |

| AD | 5.13 abc | 13.61 e | 15.20 g | 4.65 ab | 6.15 c | 4.49 a |

| Mean | 5.13 | 11.64 | 14.63 | 4.58 | 6.56 | 4.40 |

| Treatments | 2020 Vegetation Period | Autumn and Non-Vegetation Period (2AV–1AH) | 2021 Vegetation Period | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The First Half (1IG–1AV) | The Second Half (1AH–1IG) | The First Half (2IG–2AV) | The Second Half (2AH–2IG) | ||

| N0 | 4.28 ± 0.54 | 3.80 ± 0.56 | −9.15 ± 0.38 | 0.57 ± 0.37 | −2.29 ± 0.47 |

| Time × N rates | |||||

| N60 | 6.20 fg | 1.41 cd | −8.16 ab | 1.57 cd | −2.92 b |

| N120 | 6.67 g | 3.82 e | −10.96 a | 2.07 de | −3.22 b |

| N120 + 50 | 6.67 fg | 3.77 e | −11.03 a | 2.28 de | −0.34 c |

| Time × fertilizer | |||||

| AN | 5.24 ef | 3.79 ef | −9.90 a | 3.40 de | −3.12 b |

| PS | 5.81 f | 3.61 e | −9.70 a | 1.03 c | −1.70 b |

| AD | 8.49 g | 1.59 cd | −10.55 a | 1.50 cd | −1.66 b |

| Mean | 6.52 | 3.00 | −10.05 | 1.98 | −2.16 |

| Treatments | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM | Above-Ground Mass | DM | Above-Ground Mass | |||||

| g kg−1 | Change * g kg−1 | kg ha−1 DM | Change * kg ha−1 | g kg−1 | Change * g kg−1 | kg ha−1 DM | Change * kg ha−1 | |

| N0 | 280.77 c | 0.00 | 3363.6 a | 0.0 | 229.5 bcd | 0.00 | 1553.1 a | 0.0 |

| AN60 | 265.93 abc | −14.83 abc | 3690.8 abc | 327.2 ab | 217.2 abcd | −12.27 ab | 1819.5 abc | 266.4 abc |

| PS60 | 268.63 abc | −12.13 abc | 3627.8 abc | 264.2 ab | 230.8 d | 1.27 d | 1783.8 abc | 230.6 a |

| AD60 | 257.67 a | −23.10 a | 3782.8 c | 419.2 ab | 227.9 bcd | −1.63 bcd | 1763.8 ab | 210.7 a |

| AN120 | 278.83 bc | −1.93 c | 3781.9 bc | 418.3 ab | 210.4 a | −19.07 a | 2136.9 e | 583.8 c |

| PS120 | 253.90 a | −26.87 a | 3866.7 c | 503.1 b | 216.6 ab | −12.87 ab | 1876.0 bcde | 322.8 abc |

| AD120 | 262.90 abc | −17.87 abc | 3839.5 bc | 475.9 ab | 226.5 bcd | −2.97 bcd | 2064.8 cde | 511.7 abc |

| Mean | 266.9 | −16.1 | 3707.6 | 401.3 | 222.7 | −7.92 | 1856.8 | 303.7 |

| Treatments | 2020 | 2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Concentration, g kg−1 DM | N Accumulated in Biomass, kg ha−1 | NUE, % | N Concentration, g kg−1 DM | N Accumulated in Biomass, kg ha−1 | NUE, % | |

| N0 | 13.66 a | 43.6 a | - | 21.8 a | 33.9 a | - |

| AN60 | 16.39 bcd | 60.5 bcd | 28.1 bcd | 24.89 bcd | 45.2 b | 18.8 ab |

| PS60 | 15.66 ab | 56.9 b | 22.2 abcd | 22.94 ab | 41.2 ab | 11.9 ab |

| AD60 | 17.40 bcd | 66.0 bcd | 37.3 d | 23.45 ab | 41.5 ab | 12.7 ab |

| AN120 | 15.94 bcd | 60.2 b | 13.8 a | 26.98 d | 57.8 d | 19.9 b |

| PS120 | 18.11 d | 70.0 d | 22.0 ab | 24.68 abcd | 46.4 b | 10.4 ab |

| AD120 | 16.85 bcd | 64.7 bcd | 17.6 ab | 23.00 ab | 47.5 bcd | 11.4 ab |

| Mean | 16.29 | 60.3 | 23.5 | 23.96 | 44.7 | 14.2 |

| Treatments | 2020 | 2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Concentration in Grain, g kg−1 | N Accumulated in Grain–Straw Biomass, kg ha−1 | NUE, % | N Concentration in Grain, g kg−1 | N Accumulated in Grain–Straw Biomass, kg ha−1 | NUE, % | |

| N0 | 16.58 a | 67.15 a | 21.75 a | 39.00 a | ||

| AN60 | 16.65 ab | 96.82 abcd | 49.5 abc | 23.17 ab | 55.65 bc | 27.8 ab |

| PS60 | 17.67 ab | 108.80 bcd | 69.4 bc | 24.00 bcd | 57.14 bcde | 30.2 b |

| AD60 | 18.64 ab | 112.09 bcd | 74.9 c | 24.11 bcd | 48.03 ab | 15.0 ab |

| AN120 | 17.91 ab | 89.95 ab | 19.0 a | 24.35 bcd | 68.96 cde | 25.0 ab |

| PS120 | 19.23 bcde | 118.87 bcd | 43.1 abc | 23.54 b | 61.44 bcde | 18.7 ab |

| AD120 | 17.63 ab | 101.11 abcd | 28.3 abc | 23.33 b | 62.15 bcde | 19.3 ab |

| AN120 + 50 | 21.56 cde | 122.01 bcd | 32.3 abc | 24.60 bcd | 70.56 e | 18.6 ab |

| PS120 + 50 | 21.96 e | 135.54 d | 40.2 abc | 25.65 d | 65.86 cde | 15.8 ab |

| AD120 + 50 | 18.86 abc | 116.23 bcd | 28.9 abc | 25.48 cd | 66.87 cde | 16.4 ab |

| Mean | 18.78 | 106.86 | 42.8 | 24.00 | 59.56 | 20.8 |

| Treatments | Gross Energy GJ ha−1 | Gross Energy index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | Cumulative | Relative Units | |

| N0 | 59.2 a | 28.0 a | 87.2 a | 100.0 |

| AN60 | 88.2 bc | 37.4 bcd | 125.6 bc | 144.0 |

| PS60 | 90.2 bc | 38.3 bcd | 128.4 bc | 147.2 |

| AD60 | 89.3 bc | 32.0 ab | 121.3 bc | 139.1 |

| AN120 | 74.2 abc | 44.3 d | 118.5 bc | 135.9 |

| PS120 | 90.7 c | 40.8 cd | 131.5 c | 150.8 |

| AD120 | 86.8 bc | 39.7 bcd | 126.5 bc | 145.1 |

| AN120 + 50 | 84.0 bc | 43.5 cd | 127.5 bc | 146.2 |

| PS120 + 50 | 90.2 bc | 40.3 bcd | 130.5 bc | 149.7 |

| AD120 + 50 | 88.4 bc | 40.7 bcd | 129.1 bc | 148.1 |

| Mean | 84.1 | 38.5 | 122.6 | 140.6 |

| Treatments Abbreviation | Main Fertilization | Additional Fertilization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilizer Name | Fertilization Time | N Rate kg ha−1 | Fertilizer Name | Fertilization Time | N Rate kg ha−1 | |

| N0 | Unfertilized (Control) | BBCH 25 | 0 | |||

| AN60 | Ammonium nitrate | BBCH 25 | 60 | |||

| PS60 | Pig slurry | BBCH 25 | 60 | |||

| AD60 | Anaerobic digestate | BBCH 25 | 60 | |||

| AN120 | Ammonium nitrate | BBCH 25 | 120 | |||

| PS120 | Pig slurry | BBCH 25 | 120 | |||

| AD120 | Anaerobic digestate | BBCH 25 | 120 | |||

| AN120 + 50 | Ammonium nitrate | BBCH 25 | 120 | Ammonium nitrate | BBCH 35 | 50 |

| PS120 + 50 | Pig slurry | BBCH 25 | 120 | Ammonium nitrate | BBCH 35 | 50 |

| AD120 + 50 | Anaerobic digestate | BBCH 25 | 120 | Ammonium nitrate | BBCH 35 | 50 |

| Year | pH | DM | OM | Corg | Ntot | N-NH4 | N-NO3 | MHS | MHA | MFA | C/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g kg−1 | |||||||||||

| Pig slurry (PS) | |||||||||||

| 2020 | 7.65 | 31.6 | 24.1 | 7.41 | 2.36 | 1.65 | 0.018 | 3.40 | 1.18 | 2.22 | 3.14 |

| 2021 | 6.86 | 40.4 | 31.4 | 12.87 | 4.74 | 2.94 | 0.012 | 7.66 | 1.78 | 5.88 | 2.72 |

| Anaerobic digestate (AD) | |||||||||||

| 2020 | 7.72 | 27.5 | 17.2 | 10.44 | 2.76 | 1.66 | 0.009 | 4.18 | 1.78 | 2.40 | 3.78 |

| 2021 | 7.77 | 14.0 | 10.1 | 4.46 | 2.38 | 1.79 | 0.017 | 3.12 | 1.37 | 1.75 | 1.87 |

| Month | Temperature, °C | Precipitation, mm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | SCN (1991–2020) | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | SCN (1991–2020) | |

| September | 13.8 | 16.2 | 12.0 | 57.0 | 17.7 | 57.9 |

| October | 10.5 | 12.2 | 6.3 | 34.1 | 60.6 | 45.5 |

| November | 5.0 | 5.2 | 1.4 | 45.1 | 65.3 | 42.7 |

| December | 2.6 | 0.8 | −3.0 | 31.7 | 23.6 | 39.0 |

| January | 2.8 | −5.7 | −4.7 | 26.1 | 51.6 | 31.6 |

| February | 2.8 | −9.6 | −5.0 | 33.2 | 9.0 | 26.9 |

| March | 3.7 | −2.0 | −0.6 | 26.0 | 35.0 | 26.6 |

| April | 6.4 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 14.9 | 11.4 | 33.7 |

| May | 10.5 | 13.7 | 12.3 | 44.8 | 137.2 | 45.6 |

| June | 20.2 | 23.5 | 15.5 | 104.2 | 69.7 | 60.0 |

| July | 19.1 | 25.2 | 17.2 | 113.7 | 32.9 | 72.8 |

| August | 22.1 | 17.6 | 17.0 | 26.7 | 176.0 | 63.5 |

| Mean/sum | 9.96 | 13.52 | 11.04 | 557.5 | 657.1 | 545.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arlauskienė, A.; Petraitytė, D.; Palubinskas, T.; Jimenez, M.; Cesevičienė, J. Nutritional Status and Nitrogen Uptake Dynamics of Waxy-Type Winter Wheat Under Liquid Organic Fertilization. Plants 2025, 14, 3799. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243799

Arlauskienė A, Petraitytė D, Palubinskas T, Jimenez M, Cesevičienė J. Nutritional Status and Nitrogen Uptake Dynamics of Waxy-Type Winter Wheat Under Liquid Organic Fertilization. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3799. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243799

Chicago/Turabian StyleArlauskienė, Aušra, Danutė Petraitytė, Tadas Palubinskas, Marlo Jimenez, and Jurgita Cesevičienė. 2025. "Nutritional Status and Nitrogen Uptake Dynamics of Waxy-Type Winter Wheat Under Liquid Organic Fertilization" Plants 14, no. 24: 3799. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243799

APA StyleArlauskienė, A., Petraitytė, D., Palubinskas, T., Jimenez, M., & Cesevičienė, J. (2025). Nutritional Status and Nitrogen Uptake Dynamics of Waxy-Type Winter Wheat Under Liquid Organic Fertilization. Plants, 14(24), 3799. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243799