Overcoming Recalcitrance: A Review of Regeneration Methods and Challenges in Roses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Limiting Factors in Rose Regeneration

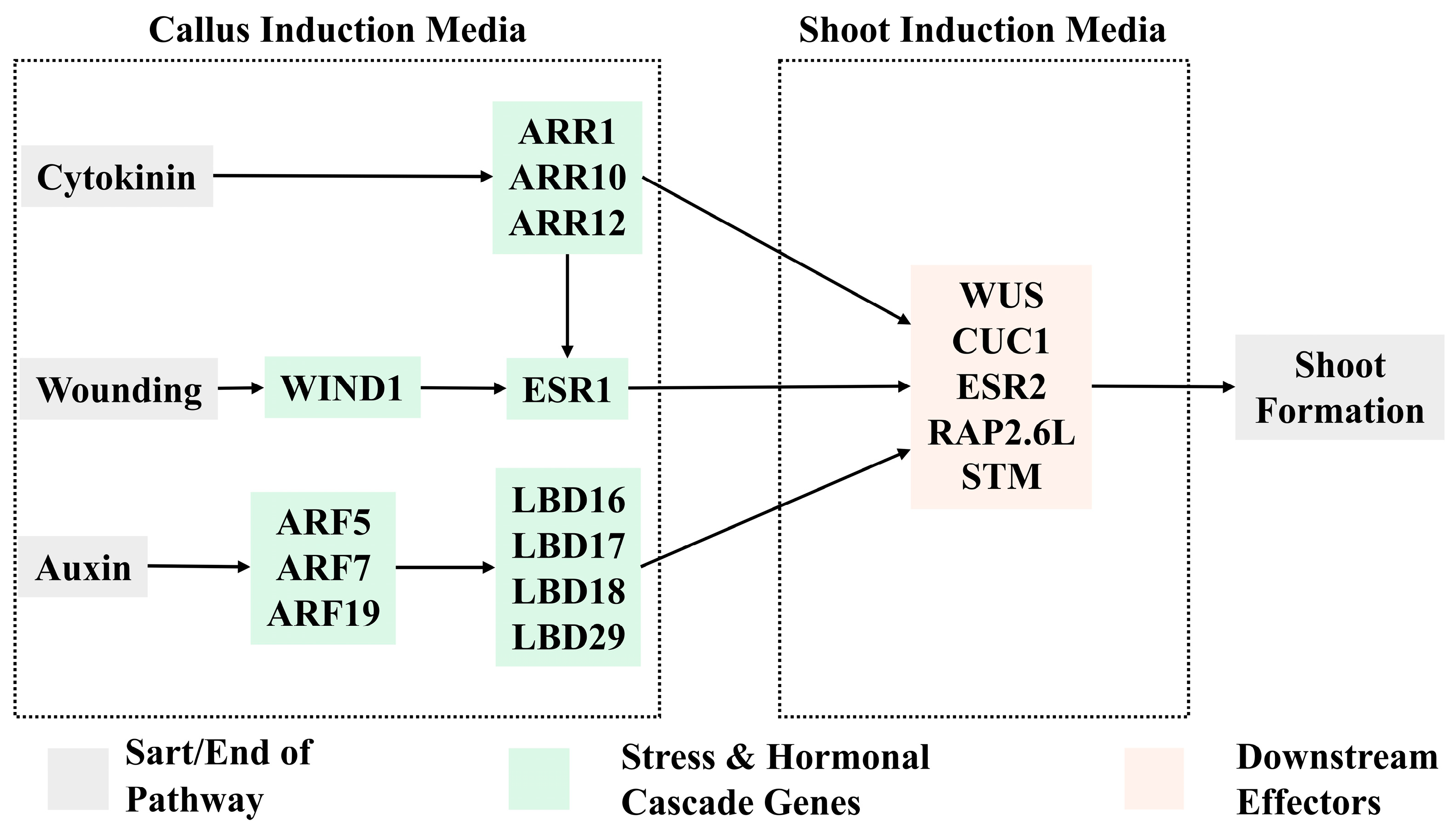

3. Model of Plant Regeneration in Rose Tissue Culture

4. Molecular Pathways of Regeneration

5. Biochemistry of Rose Regeneration

6. Advances in Rose Tissue Culture (1990–2025)

6.1. Environmental Conditions–Temperature

6.2. Environmental Conditions–Liquid Cultures

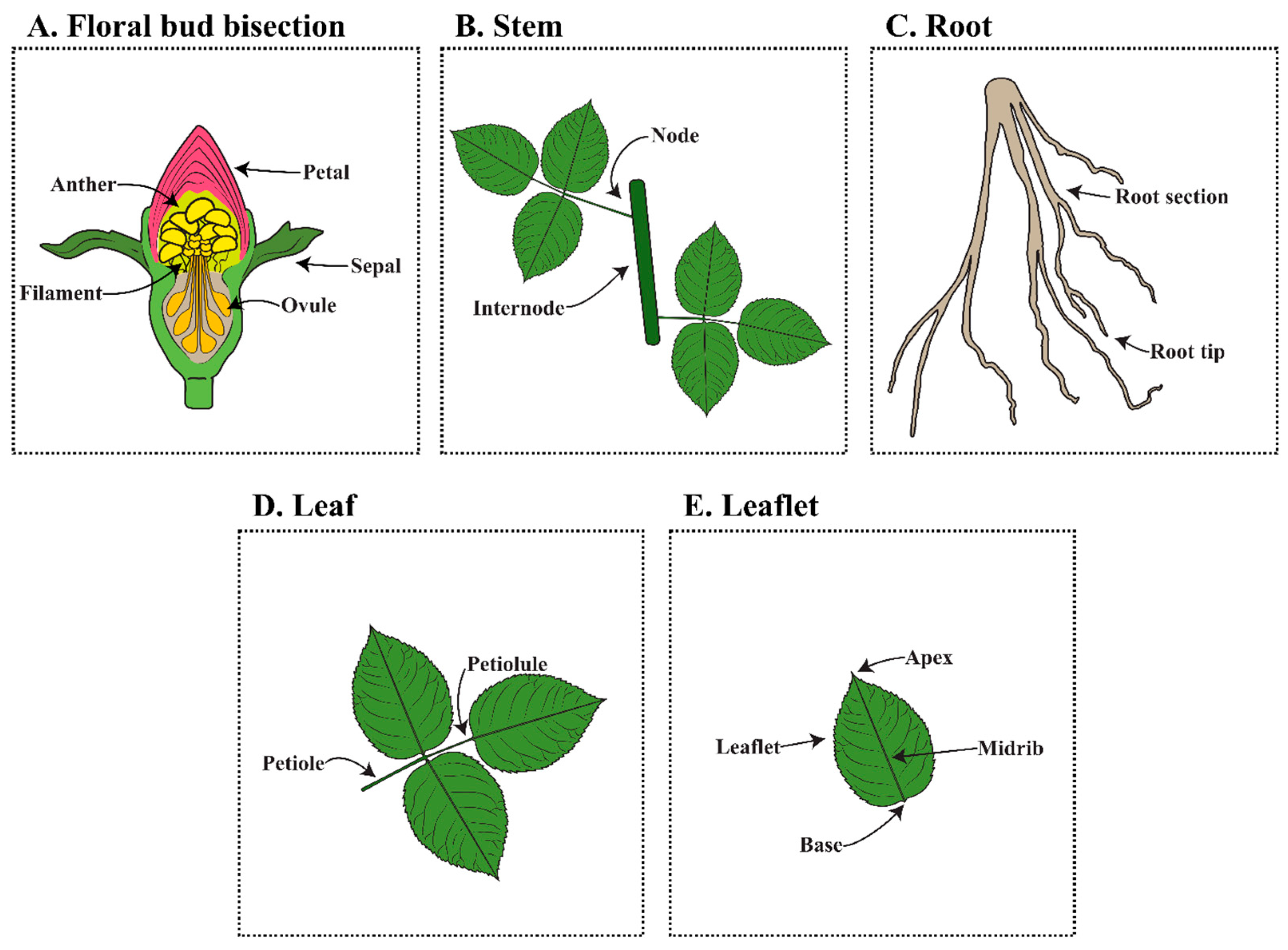

6.3. Explant Source and Selection

| Explant Source | Regeneration Type | Cultivar | Associated Publications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthers | Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Meirutral’ | Arene et al., 1993 [72] |

| Embryos | Organogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Bridal Pink’ × pollen parents (also R. hybrida) | Burger et al., 1990 [62] |

| R. hybrida ‘Shortcake’ | Asano and Tanimoto, 2002 [73] | ||

| Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Meirutral’ | Arene et al., 1993 [72] | |

| Somatic Embryogenesis | R. rugosa Thunb. | Kunitake et al., 1993 [57] | |

| R.rugosa | Kim et al., 2004 [32] | ||

| R.bourboniana | Kaur et al., 2006 [33] | ||

| Filaments | Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Royalty’ | Noriega and Söndahl, 1991 [74] |

| Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Royalty’ | Firoozabady et al., 1994 [75] | |

| R. hybrida ‘Tournament of Roses’ | Burrell et al., 2006 [31] | ||

| Ovules | Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Meirutral’ | Arene et al., 1993 [72] |

| Petals | Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Meirutral’ | Arene et al., 1993 [72] |

| Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Anny’ | Borissova et al., 2000 [24] | |

| Sepals | Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Meirutral’ | Arene et al., 1993 [72] |

| Internodal Stem Segments | Organogenesis | R. chinensis minima ‘Baby Katie’ R. chinensis minima ‘Red Sunblaze’ | Hsia and Korban, 1996 [61] |

| Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Meirutral’ | Arene et al., 1993 [72] | |

| R. hybrida ‘Charming’ | Kim et al., 2004 [32] | ||

| Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Landora’ | Rout et al., 1991 [70] | |

| Leaflet Sections | Organogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Sonia’ | Derks et al., 1995 [76] |

| R. hybrida ‘Lavande’ | Katsumoto et al., 2007 [25] | ||

| R. chinensis minima ‘Baby Katie’ R. chinensis minima ‘Red Sunblaze’ | Hsia and Korban, 1996 [61] | ||

| Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Apollo’ | Pourhosseini et al., 2013 [35] | |

| R. hybrida ‘Eiffel Tower’ | Mahmoud et al., 2018 [21] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Carefree Beauty’ | Hsia and Korban, 1996 [61] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Tineke’ | Kim et al., 2004 [32] | ||

| Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Tournament of Roses’ | Burrell et al., 2006 [31] | |

| R. hybrida ‘Livin’ Easy’ | Estabrooks et al., 2007 [59] | ||

| R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ | Cai et al., 2022 [20] | ||

| Petioles | Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Glad Tidings’ | Marchant et al., 1998 [77] |

| Leaflets | Organogenesis | R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ R. hybrida ‘Delstrimen’ R. hybrida ‘Félicité et Perpétue’ R. hybrida ‘Natal Briar’ R. hybrida ‘White Pet’ R. wichurana | Hamama et al., 2019 [30] |

| Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Heckenzauber’ R. hybrida ‘Pariser Charme’ R. indica | Dohm et al., 2001 [22] | |

| R. hybrida ‘Italian Ice’ R. hybrida ‘Ringo All-Star’ R. hybrida ‘Carefree Beauty’ | Harmon et al., 2022 [78] | ||

| Organogenesis; Protocorm-Like Bodies | R. multiflora var. cathayensis R. multiflora f. carnea | Tian et al., 2008 [49] | |

| Protocorm-Like Bodies | R. canina | Kou et al., 2016 [79] | |

| Somatic Embryogenesis | R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ | Cai et al., 2022 [20] | |

| R. hybrida ‘Domingo’ R. hybrida ‘Vickey Brown’ | de Wit et al., 1990 [37] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Heckenzauber’ | Dohm et al., 2001 [22] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Landora’ | Das et al., 2010 [80] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Samantha’ | Bao et al., 2012 [19] | ||

| Leaves | Organogenesis | R. damascena ‘Jwala’ | Pati et al., 2004 [38] |

| R. hybrida ‘Amanda’ R. hybrida ‘Black Baccara’ R. hybrida ‘Maroussia’ R. hybrida ‘Apollo’ | Pourhosseini et al., 2013 [35] | ||

| R. sp. | Nguyen et al., 2017 [23] | ||

| Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Carefree Beauty’ | Arene et al., 1993 [72] | |

| R. hybrida ‘Meirutral’ | Li et al., 2002 [36] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Charming’ R. hybrida ‘4th of July’ R. hybrida ‘Tournament of Roses’ | Kim et al., 2004 [32] | ||

| Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis; Secondary Somatic Embryogenesis | R. chinensis ‘Jacq.’ | Chen et al., 2014 [58] | |

| Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Landora’ | Rout et al., 1991 [70] | |

| R. hybrida ‘Soraya’ | Kintzios et al., 1999 [26] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Saltze Gold’ | Borissova et al., 2000 [24] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Heckenzauber’ R. hybrida ‘Pariser Charme’ | Dohm et al., 2001 [22] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Trimontsium’ | Borissova et al., 2005 [81] | ||

| R. chinensis ‘Jacq.’ | Chen et al., 2010 [65] | ||

| R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’ | Vergne et al., 2010 [69] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Linda’ | Zakizadeh et al., 2013 [82] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘E.H.L.Krause RI | Randoux et al., 2014 [66] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Samantha’ | Liu et al., 2021 [15] Wang et al., 2023 [17] | ||

| R. hybrida ‘Carola’ | Duan et al., 2024 [67] | ||

| Somatic Embryogenesis; Secondary Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Carefree Beauty’ | Li et al., 2002 [36] | |

| Roots | Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Meirutral’ | Arene et al., 1993 [72] |

| R. hybrida ‘Charming’ | Kim et al., 2004 [32] | ||

| Somatic Embryogenesis | R. persica × xanthina | Matthews et al., 1991 [63] | |

| R. hybrida ‘Fresham’ | Yokoya et al., 1996 [71] | ||

| Not Specified | Organogenesis; Somatic Embryogenesis | R. hybrida ‘Pariser Charme’ R. persica × R. xanthina R. hybrida ‘Elina’ | Schum et al., 2001 [64] |

| Somatic Embryogenesis | R. floribunda ‘Trumpeter’ R. hybrida ‘Dr. Huey’ R. multiflora ‘Tineké’ | Castillón and Kamo, 2002 [34] |

6.4. Media Composition

| Media Composition | Associated PGRs | Environmental Conditions | Associated Publications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MS Modified vitamins Fructose; Glucose; Maltose; Sucrose | BAP; Fe-EDDHA; IBA; TDZ | 21 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Hamama et al., 2019 [30] |

| MS Modified vitamins Sucrose | GA3; NAA; Zeatin | 24 ± 1 °C Dark conditions | Noriega and Söndahl, 1991 [74] |

| BAP; IAA | 25 ± 1 °C Dark conditions | Firoozabady et al., 1994 [75] | |

| 2,4-D | 25 °C Dark conditions | Castillón and Kamo, 2002 [34] | |

| Dicamba; IBA; Kinetin | 25 ± 1 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Kim et al., 2004 [32] | |

| 2,4-D; BAP; GA3 | 25 ± 2 °C 16-h photoperiod | Das et al., 2010 [80] | |

| MS Morel and Martin Vitamins Sucrose | 2,4-D; BAP | 23 °C 16-h photoperiod | Arene et al., 1993 [72] |

| MS Morel and Wetmore Vitamins Sucrose | AgNO3; BAP; GA3; NAA | 25 ± 1 °C 16-h photoperiod | Mahmoud et al., 2018 [21] |

| MS MS Vitamins Fructose; Glucose; Maltose; Sorbitol; Sucrose | 2,4-D; Adenine; BAP; Kinetin; NAA; Picloram; Zeatin | 25 °C Continuous photoperiod | Kunitake et al., 1993 [57] |

| MS MS Vitamins Fructose; Glucose; Sucrose | 2,4,5-T; 2,4-D; BAP; TDZ | 23 °C Dark conditions Photoperiod (not described) | Harmon et al., 2022 [78] |

| MS MS Vitamins Glucose | 2,4-D; BAP; TDZ | 24 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 14 h photoperiod | Bao et al., 2012 [19] |

| AgNO3; BAP; IBA; TDZ | 23 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Nguyen et al., 2017 [23] | |

| 2,4-D; BAP; GA3; Kinetin; NAA | 22 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Liu et al., 2021 [15] | |

| BAP; IBA; NAA; Zeatin | 25 ± 1 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Duan et al., 2024 [67] | |

| MS MS Vitamins Mannitol; Sucrose | GA3; IBA; NAA; Zeatin | 25 °C Dark conditions light conditions | Vergne et al., 2010 [69] |

| MS MS Vitamins Sucrose | Kinetin; NAA | 20 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | de Wit et al., 1990 [37] |

| 2,4-D; Adenine sulfate; BAP; GA3; NAA | 25 ± 2 °C; 8 ± 1 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Rout et al., 1991 [70] | |

| GA3; TDZ | 22 ± 1 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Hsia and Korban, 1996 [61] | |

| BAP; IAA; Kinetin; pCPA | 25 °C 16-h photoperiod | Kintzios et al., 1999 [26] | |

| 2-iP; Dicamba; Kinetin | 25 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Borissova et al., 2000 [24] | |

| GA3; NAA; Zeatin | 25 °C Ambient photoperiod (not described) 90 rpm 23 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Dohm et al., 2001 [22] | |

| BAP; NAA | 25 °C Photoperiod (not described) | Asano and Tanimoto, 2002 [73] | |

| 2,4-D | 25 °C 16-h photoperiod | Kim et al., 2004 [32] | |

| 2,4-D; Zeatin | 25 °C Dark conditions 16 h photoperiod | Kim et al., 2004 [32] | |

| AgNO3; BAP; NAA; TDZ | 25 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 14 h photoperiod | Pati et al., 2004 [38] | |

| 2-iP; 2,4-D; ABA; BAP; Dicamba; GA3; Kinetin | 25 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Borissova et al., 2005 [81] | |

| 2,4-D; BAP | 25 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Kaur et al., 2006 [33] | |

| 2,4,5-T; ABA | 22 °C Dark conditions | Estabrooks et al., 2007 [59] | |

| BAP | 25 °C 16-h photoperiod | Katsumoto et al., 2007 [25] | |

| 2,4-D; BAP; GA3; IBA; TDZ | 25 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Tian et al., 2008 [49] | |

| 2,4-D; BAP; GA3; IBA; Kinetin; NAA; NPA; TDZ | 25 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Kou et al., 2016 [79] | |

| 2,4-D; GA3; TDZ | 23 ± 1 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Li et al., 2002 [36] | |

| 2,4-D; GA3;TDZ 2,4-D; ABA; BAP; GA3; NAA; TDZ; Zeatin | 22 ± 2 °C Dark conditions | Pourhosseini et al., 2013 [35] | |

| 23 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Zakizadeh et al., 2013 [68] | ||

| MS Staba Vitamins Glucose; Sucrose | 2,4-D; BAP | Not described | Randoux et al., 2014 [66] |

| 2,4-D; Zeatin | 24 ± 3 °C Dark conditions | Burrell et al., 2006 [31] | |

| MS; B5 MS Vitamins; B5 Vitamins Glucose; Sucrose | 2,4-D; BAP; IBA; NAA | 22 °C Dark conditions Photoperiod (not described) | Derks et al., 1995 [76] |

| MS; SH Modified vitamins Sucrose | 2,4-D; BAP; GA3; Kinetin | 25 ± 2 °C 16-h photoperiod | Cai et al., 2022 [20] |

| MS; SH MS Vitamins; SH Vitamins Sucrose | 2,4-D | 25 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Schum et al., 2001 [64] |

| Not described | 25 °C Dark conditions 130 rpm | Wang et al., 2023 [17] | |

| 2,4-D | 25 °C Dark conditions Photoperiod (not described) | Matthews et al., 1991 [63] | |

| SH Modified vitamins Sucrose | 2,4-D; BAP; NAA | 25 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Kim et al., 2004 [32] |

| 2,4-D; TDZ | 24 °C; 4 °C Dark conditions Photoperiod (not described) | Yokoya et al., 1996 [71] | |

| SH SH Vitamins Maltose; Sucrose | 2,4-D; ABA; GA3; TDZ | 25 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h photoperiod | Chen et al., 2010 [65] |

| SH SH Vitamins Sucrose | 2,4-D; ABA; GA3; TDZ | 25 ± 2 °C Dark conditions 16-h Photoperiod (not described); red light; white light | Chen et al., 2014 [58] |

6.5. Plant Growth Regulators (PGRs)

7. Organic and Inorganic Additives

8. Case Studies

8.1. ‘Samantha’

8.2. ‘Carefree Beauty’

8.3. ‘Rosaceae Crops’

9. Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic Acid |

| pCPA | P-Chlorophenoxyacetic Acid |

| BAP | 6-Benzylaminopurine |

| B5 | Gamborg B-5 medium |

| BBM | BABY BOOM gene |

| Fe-EDDHA | Iron(III) ethylenediamine-N,N′-bis(2-hydroxyphenylacetic) acid |

| GA3 | Gibberellic Acid |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic Acid |

| IBA | Indole-3-butyric Acid |

| MFs | Morphogenetic Factors |

| MS | Murashige and Skoog |

| NAA | Naphthaleneacetic acid |

| NPA | N-1-naphthylphthalamic Acid |

| POD | Superoxide Peroxidase |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SH | Schenk and Hildebrandt medium |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| TDZ | Thidiazuron |

| 2,4-D | 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid |

| 2,4,5-T | 2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxyacetic Acid |

| WUS | WUSCHEL gene |

References

- Rihn, A.L.; Yue, C.; Hall, C.; Behe, B.K. Consumer Preferences for Longevity Information and Guarantees on Cut Flower Arrangements. HortScience 2014, 49, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, D.E.; Palma, M.A.; Byrne, D.H.; Hall, C.R.; Ribera, L.A. Willingness to Pay for Rose Attributes: Helping Provide Consumer Orientation to Breeding Programs. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Beneficial Medicinal Effects and Material Applications of Rose. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oargă (Porumb), D.P.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Cordea, M.I. Unveiling the Mechanisms for the Development of Rosehip-Based Dermatological Products: An Updated Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1390419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasery, M.; Hassanzadeh, M.; Najaran, Z.T.; Emami, S.A. Rose (Rosa × Damascena Mill.) Essential Oils. In Essential Oils in Food Preservation, Flavor, and Safety; Preedy, V.R., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 659–665. ISBN 978-0-12-416641-7. [Google Scholar]

- Joshel, C.; Melnicoe, R. Crop Timeline for California Greenhouse Grown Cut Roses; Western IPM Center, University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail, V.J.; Kevan, P.G. Review of the Breeding Systems of Wild Roses (Rosa spp.). Floric. Ornam. Biotechnol. 2009, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Meral, E.D. Crossability of Miniature Rose and Quantitative and Qualitative Traits in Hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1244426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, D.H.; Klein, P.; Yan, M.; Young, E.; Lau, J.; Ong, K.; Shires, M.; Olson, J.; Windham, M.; Evans, T.; et al. Challenges of Breeding Rose Rosette–Resistant Roses. HortScience 2018, 53, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Huang, B.; Yan, X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, S.; Wu, Q.; Bao, M.; Bendahmane, M.; Fu, X. Identification of Distinct Roses Suitable for Future Breeding by Phenotypic and Genotypic Evaluations of 192 Rose Germplasms. Hortic. Adv. 2024, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, D.D.; Chen, H.; Byrne, D.; Liu, W.; Ranney, T.G. Cytogenetics, Ploidy, and Genome Sizes of Rose (Rosa spp.) Cultivars and Breeding Lines. Ornam. Plant Res. 2023, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukosavljev, M.; Zhang, J.; Esselink, G.D.; Van ‘T Westende, W.P.C.; Cox, P.; Visser, R.G.F.; Arens, P.; Smulders, M.J.M. Genetic Diversity and Differentiation in Roses: A Garden Rose Perspective. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 162, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altpeter, F.; Baisakh, N.; Beachy, R.; Bock, R.; Capell, T.; Christou, P.; Daniell, H.; Datta, K.; Datta, S.; Dix, P.J.; et al. Particle bombardment and the genetic enhancement of crops: Myths and realities. Mol. Breed. 2005, 15, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsch, R.B.; Fry, J.E.; Hoffmann, N.L.; Eichholtz, D.; Rogers, S.G.; Fraley, R.T. A simple and general method for transferring genes into plants. Science 1985, 227, 1229–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, H.; Bao, Y.; Ning, G.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, H.; Gao, J.; Ma, N. Agrobacterium Tumefaciens-Mediated Transformation of Modern Rose (Rosa hybrida) Using Leaf-Derived Embryogenic Callus. Hortic. Plant J. 2021, 7, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, K.; Harmon, D.; Nelson, A.; Leng, H.; McLennan, S.; Nix, C.; Kinsch, E.; Leoshko, G.; Hall, G.; Huang, D.; et al. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of rose meristem in vitro. Acta Hortic. 2024, 1404, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Yu, Q.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, X.; Ma, N. An efficient CRISPR/Cas9 platform for targeted genome editing in rose (Rosa hybrida). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.F.; Wang, J.H.; Feng, H.; Li, Y.; Shi, X.B. Establishment of plant regeneration from leaves explants of Rosa hybrida. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2004, 34, 533–536. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y.; Liu, G.; Shi, X.; Wen, X.; Ning, G.; Liu, J.; Bao, M. Primary and repetitive secondary somatic embryogenesis in Rosa hybrida ‘Samantha’. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 2012, 109, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Tang, L.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Chen, J. Somatic embryogenesis in Rosa chinensis cv. ‘Old Blush’. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 2022, 149, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.M.A.; Hassanein, A.M.A. Essential factors for in vitro regeneration of rose and a protocol for plant regeneration from leaves. Hortic. Sci. 2018, 45, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohm, A.; Ludwig, C.; Nehring, K.; Debener, T. Somatic Embryogenesis in Roses. Acta Hortic. 2001, 547, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.N.; Schulz, D.; Winkelmann, T.; Debener, T. Genetic Dissection of Adventitious Shoot Regeneration in Roses by Employing Genome-Wide Association Studies. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 1493–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borissova, A.; Tsolova, V.; Angeliev, V.; Atanassov, A. Somatic Embryogenesis of Rosa hybrida L. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2000, 14, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Katsumoto, Y.; Fukuchi-Mizutani, M.; Fukui, Y.; Brugliera, F.; Holton, T.A.; Karan, M.; Nakamura, N.; Yonekura-Sakakibara, K.; Togami, J.; Pigeaire, A.; et al. Engineering of the Rose Flavonoid Biosynthetic Pathway Successfully Generated Blue-Hued Flowers Accumulating Delphinidin. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007, 48, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kintzios, S.; Manos, C.; Makri, O. Somatic Embryogenesis from Mature Leaves of Rose (Rosa sp.). Plant Cell Rep. 1999, 18, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Oh, M.J.; Liu, J.R. Somatic Embryogenesis and Plant Regeneration in Zygotic Embryo Explant Cultures of Rugosa Rose. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2009, 3, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Trinh, M.D.L.; Falkenberg, M.K.D.; Chiurazzi, M.J.; Najafi, J.; Nørrevang, A.F.; Correia, P.M.P.; Palmgren, M. Unlocking in Vitro Transformation of Recalcitrant Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 1306–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, A.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, A.; Yang, X.; Ming, M.; Cao, F.; Fu, F. Application of Developmental Regulators for Enhancing Plant Regeneration and Genetic Transformation. Plants 2024, 13, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama, L.; Voisine, L.; Pierre, S.; Cesbron, D.; Ogé, L.; Lecerf, M.; Cailleux, S.; Bosselut, J.; Foucrier, S.; Foucher, F.; et al. Improvement of in Vitro Donor Plant Competence to Increase de Novo Shoot Organogenesis in Rose Genotypes. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 252, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, A.M.; Lineberger, R.D.; Rathore, K.S.; Byrne, D.H. Genetic Variation in Somatic Embryogenesis of Rose. HortScience 2006, 41, 1165–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.K.; Oh, J.Y.; Chung, J.D.; Burrell, A.M.; Byrne, D.H. Somatic Embryogenesis and Plant Regeneration from In-Vitro-Grown Leaf Explants of Rose. HortScience 2004, 39, 1378–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Pati, P.K.; Sharma, M.; Ahuja, P.S. Somatic Embryogenesis from Immature Zygotic Embryos of Rosa Bourboniana Desp. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2006, 42, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillón, J.; Kamo, K. Maturation and Conversion of Somatic Embryos of Three Genetically Diverse Rose Cultivars. HortScience 2002, 37, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhosseini, L.; Kermani, M.J.; Habashi, A.A.; Khalighi, A. Efficiency of Direct and Indirect Shoot Organogenesis in Different Genotypes of Rosa hybrida. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2013, 112, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Krasnyanski, S.F.; Korban, S.S. Somatic Embryogenesis, Secondary Somatic Embryogenesis, and Shoot Organogenesis in Rosa. J. Plant Physiol. 2002, 159, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, J.C.; Esendam, H.F.; Honkanen, J.J.; Tuominen, U. Somatic Embryogenesis and Regeneration of Flowering Plants in Rose. Plant Cell Rep. 1990, 9, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, P.K.; Sharma, M.; Sood, A.; Ahuja, P.S. Direct Shoot Regeneration from Leaf Explants of Rosa Damascena Mill. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2004, 40, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Yang, Y.; Pan, G.; Shen, Y. New Insights Into Tissue Culture Plant-Regeneration Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 926752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, F.L.; Kaeppler, H.F. History and Current Status of Embryogenic Culture-Based Tissue Culture, Transformation and Gene Editing of Maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Genome 2025, 18, e20451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minocha, R.; Jain, S.M. (Eds.) Tissue Culture of Woody Plants and Its Relevance to Molecular Biology. In Molecular Biology of Woody Plants; Forestry Sciences; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 64, pp. 315–339. ISBN 978-90-481-5338-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra, S.; Goel, M.K.; Kukreja, A.K.; Mishra, B.N. Efficiency of Liquid Culture Systems over Conventional Micropropagation: A Progress towards Commercialization. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Le, V. Co-Transformation of Oil Palm Using Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation. Nat. Preced. 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Li, G.; Malzahn, A.A.; Cheng, Y.; Leyson, B.; Sretenovic, S.; Gurel, F.; Coleman, G.D.; Qi, Y. Boosting Plant Genome Editing with a Versatile CRISPR-Combo System. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scintilla, S.; Salvagnin, U.; Giacomelli, L.; Zeilmaker, T.; Malnoy, M.A.; Rouppe Van Der Voort, J.; Moser, C. Regeneration of Non-Chimeric Plants from DNA-Free Edited Grapevine Protoplasts. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1078931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwase, A.; Harashima, H.; Ikeuchi, M.; Rymen, B.; Ohnuma, M.; Komaki, S.; Morohashi, K.; Kurata, T.; Nakata, M.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; et al. WIND1 Promotes Shoot Regeneration through Transcriptional Activation of ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION1 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaün, C.; Lepiniec, L.; Dubreucq, B. Genetic and Molecular Control of Somatic Embryogenesis. Plants 2021, 10, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.-L.; Abdurazak, I.; Xi, L.; Gao, B.; Wang, L.; Tian, C.-W.; Zhao, L.-J. Morphohistological Analysis of the Origin and Development of Rosa Canina Protocorm-like Bodies. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 167, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, L. Plant Regeneration through Protocorm-like Bodies Induced from Rhizoids Using Leaf Explants of Rosa spp. Plant Cell Rep. 2008, 27, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.F.; Kou, Y.P.; Gao, B.; Soliman, T.M.A.; Xu, K.D.; Ma, N.; Cao, X.; Zhao, L.J. Identification and Functional Analysis of BABY BOOM Genes from Rosa Canina. Biol. Plant. 2014, 58, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Kuang, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhan, M.; Li, C.; et al. Overexpression of RcFUSCA3, a B3 Transcription Factor from the PLB in Rosa Canina, Activates Starch Accumulation and Induces Male Sterility in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2018, 133, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Liu, K.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, L. A MADS-Box Gene Associated with Protocorm-like Body Formation in Rosa Canina Alters Floral Organ Development in Arabidopsis. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2017, 98, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Da Silva, J.A.T.; Fujita, M. Plant Response and Tolerance to Abiotic Oxidative Stress: Antioxidant Defense Is a Key Factor. In Crop Stress and Its Management: Perspectives and Strategies; Venkateswarlu, B., Shanker, A.K., Shanker, C., Maheswari, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 261–315. ISBN 978-94-007-2219-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.J.; Duan, M.; Zhou, C.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, P.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Shen, Q.; Ji, P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Antioxidant Defense System in Plants: Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Signaling, and Scavenging During Abiotic Stress-Induced Oxidative Damage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Kang, X.; Hu, X.; Wu, R.; Yuan, M.; Weng, S.; Du, L. Study on Physiological and Biochemical Characteristics Being Used for Identification of Different Plantlet Regeneration Approaches from Somatic Embryo of Rosa hybrida ‘J. F. Kennedy’. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2024, 159, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Qin, Z.; Pei, H. Reactive Oxygen and Related Regulatory Factors Involved in Ethylene-Induced Petal Abscission in Roses. Plants 2024, 13, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunitake, H.; Imamizo, H.; Mii, M. Somatic Embryogenesis and Plant Regeneration from Immature Seed-Derived Calli of Rugosa Rose (Rosa Rugosa Thunb.). Plant Sci. 1993, 90, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-R.; Wu, L.; Hu, B.-W.; Yi, X.; Liu, R.; Deng, Z.-N.; Xiong, X.-Y. The Influence of Plant Growth Regulators and Light Quality on Somatic Embryogenesis in China Rose (Rosa Chinensis Jacq.). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 33, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estabrooks, T.; Browne, R.; Dong, Z. 2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxyacetic Acid Promotes Somatic Embryogenesis in the Rose Cultivar ‘Livin’ Easy’ (Rosa sp.). Plant Cell Rep. 2007, 26, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, Y. Effects of Plant Growth Regulators on the Callus of Rose Leaves. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2023, 52, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, C.; Korban, S.S. Organogenesis and Somatic Embryogenesis in Callus Cultures of Rosa hybrida and Rosa Chinensis Minima. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1996, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, D.W.; Liu, L.; Zary, K.W.; Lee, C.I. Organogenesis and Plant Regeneration from Immature Embryos of Rosa hybrida L. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1990, 21, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.; Mottley, J.; Horan, I.; Roberts, A.V. A Protoplast to Plant System in Roses. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1991, 24, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schum, A.; Hofmann, K. Use of Isolated Protoplasts in Rose Breeding. Acta Hortic. 2001, 547, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-R.; Lü, J.-J.; Liu, R.; Xiong, X.-Y.; Wang, T.; Chen, S.-Y.; Guo, L.-B.; Wang, H.-F. DREB1C from Medicago Truncatula Enhances Freezing Tolerance in Transgenic M. Truncatula and China Rose (Rosa chinensis Jacq.). Plant Growth Regul. 2010, 60, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randoux, M.; Davière, J.; Jeauffre, J.; Thouroude, T.; Pierre, S.; Toualbia, Y.; Perrotte, J.; Reynoird, J.; Jammes, M.; Hibrand-Saint Oyant, L.; et al. RoKSN, a Floral Repressor, Forms Protein Complexes with RoFD and RoFT to Regulate Vegetative and Reproductive Development in Rose. New Phytol. 2014, 202, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Wang, S.; Jia, R.; Zhao, X.; Kou, Y.; Su, K.; et al. Somatic Embryogenesis from the Leaf-Derived Calli of In Vitro Shoot-Regenerated Plantlets of Rosa hybrida ‘Carola. Plants 2024, 13, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakizadeh, H.; Debener, T.; Sriskandarajah, S.; Frello, S.; Serek, M. Regeneration of Miniature Potted Rose (Rosa hybrida L.) via Somatic Embryogenesis. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2008, 73, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergne, P.; Maene, M.; Gabant, G.; Chauvet, A.; Debener, T.; Bendahmane, M. Somatic Embryogenesis and Transformation of the Diploid Rosa Chinensis Cv Old Blush. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2010, 100, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, G.R.; Debata, B.K.; Das, P. Somatic Embryogenesis in Callus Cultures of Rosa hybrida L. cv. Landora. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1991, 27, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoya, K.; Walker, S.; Sarasan, V. Regeneration of Rose Plants from Cell and Tissue Cultures. Acta Hortic. 1996, 424, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arene, L.; Pellegrino, C.; Gudin, S. A Comparison of the Somaclonal Variation Level of Rosa hybrida L. cv Meirutral Plants Regenerated from Callus or Direct Induction from Different Vegetative and Embryonic Tissues. Euphytica 1993, 71, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, G.; Tanimoto, S. Plant Regeneration from Embryogenic Calli Derived from Immature Seeds in Miniature Rose Cultivar. ‘Shortcake’; Somaclonal Variation, Cytological Study and RAPD Analysis. Plant Biotechnol. 2002, 19, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Noriega, C.; Söndahl, M.R. Somatic Embryogenesis in Hybrid Tea Roses. Bio Technol. 1991, 9, 991–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozabady, E.; Moy, Y.; Courtney-Gutterson, N.; Robinson, K. Regeneration of Transgenic Rose (Rosa hybrida) Plants from Embryogenic Tissue. Nat. Biotechnol. 1994, 12, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, F.H.M.; Van Dijk, A.J.; Hänisch Ten Cate, C.H.; Florack, D.E.A.; Dubois, L.A.M.; De Vries, D.P. Prolongation of Vase Life of Cut Roses via Introduction of Genes Coding for Antibacterial Activity, Somatic Embryogenesis and Agrobacterium-Mediated Tranformation. Acta Hortic. 1995, 405, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, R.; Power, J.B.; Lucas, J.A.; Davey, M.R. Biolistic Transformation of Rose (Rosa hybrida L.). Ann. Bot. 1998, 81, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, D.D.; Touchell, D.H.; Ranney, T.G.; Da, K.; Liu, W. Tissue Culture and Regeneration of Three Rose Cultivars. HortScience 2022, 57, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Yuan, C.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, G.; Nie, J.; Ma, Z.; Cheng, C.; Teixeira Da Silva, J.A.; Zhao, L. Thidiazuron Triggers Morphogenesis in Rosa canina L. Protocorm-Like Bodies by Changing Incipient Cell Fate. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P. Mass Cloning of Rose and Mussaenda, Popular Garden Plants, via Somatic Embryogenesis. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 37, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borissova, A.; Hvarleva, T.; Bedzhov, I.; Kondakova, V.; Atanassov, A.; Atanassov, I. Agrobacterium—Mediated Transformation of Secondary Somatic Embryos from Rosa hybrida L. and Recovery of Transgenic Plants. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2005, 19, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakizadeh, H.; Lütken, H.; Sriskandarajah, S.; Serek, M.; Müller, R. Transformation of Miniature Potted Rose (Rosa hybrida cv. Linda) with P SAG12 -Ipt Gene Delays Leaf Senescence and Enhances Resistance to Exogenous Ethylene. Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosh-Khui, M.; Sink, K.C. Callus Induction and Culture of Rosa. Sci. Hortic. 1982, 17, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samiei, L.; Davoudi Pahnehkolayi, M.; Tehranifar, A.; Karimian, Z. Organic and Inorganic Elicitors Enhance in Vitro Regeneration of Rosa Canina. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Krasnyanski, S.F.; Korban, S.S. Optimization of the uidA Gene Transfer into Somatic Embryos of Rose via Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2002, 40, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gasic, K.; Cammue, B.; Broekaert, W.; Korban, S.S. Transgenic Rose Lines Harboring an Antimicrobial Protein Gene, Ace-AMP1, Demonstrate Enhanced Resistance to Powdery Mildew (Sphaerotheca pannosa). Planta 2003, 218, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, K.; Yazhi, L.; Huairui, S. Plant Regeneration from Callus of in Vitro Apple Leaves. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 1995, 9, 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Da, K.; Song, Z.; Yazhi, L. Somatic Embryogenesis from Petiole in Apple. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 1996, 10, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- James, D.J.; Passey, A.J.; Rugini, E. Factors Affecting High Frequency Plant Regeneration from Apple Leaf Tissues Cultured in Vitro. J. Plant Physiol. 1988, 132, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar-Tábori, K.; Dobránszki, J.; Teixeira Da Silva, J.A.; Bulley, S.M.; Hudák, I. The Role of Cytokinins in Shoot Organogenesis in Apple. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2010, 101, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, K.; Song, Z.; Mi, R.; Zhou, Z.; Wei, Q.; Shu, H. Wounding Induced Efficient Direct Somatic Embryogenesis in Apple Leaves. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 2001, 15, 290–293. [Google Scholar]

- Aldwinkle, H.; Maloy, M. Plant Regeneration and Transformation in the Rosaceae. Transgenic Plant J. 2009, 3, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria, H.; Hussein, G.M.; Abdel-Hadi, A.-H.A.; Abdallah, N.A. Improved Regeneration and Transformation Protocols for Three Strawberry Cultivars. GM Crops Food 2014, 5, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, W.; Zohora, S.; Talukder, A.I.; Kayess, O. Effect of Different Hormone Combinations on Callus Induction and Plant Regeneration of Strawberry. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 3, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Palei, S.; Rout, G.R.; Das, A.K.; Dash, D.K. Callus Induction and Indirect Regeneration of Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa) Duch. CV. Chandler. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folta, K.M.; Dhingra, A. Invited Review: Transformation of Strawberry: The Basis for Translational Genomics in Rosaceae. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2006, 42, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakulin, S.D.; Monakhos, S.G.; Bruskin, S.A. Morphogenetic Factors as a Tool for Enhancing Plant Regeneration Capacity During In Vitro Transformation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clough, S.J.; Bent, A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998, 16, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, H.; Linghu, Q.; Nagira, Y.; Miki, R.; Taoka, N.; Imai, R. An in planta biolistic method for stable wheat transformation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nelson, A.; Ranney, T.; Liu, W.; Kelliher, T.; Duan, H.; Da, K. Overcoming Recalcitrance: A Review of Regeneration Methods and Challenges in Roses. Plants 2025, 14, 3797. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243797

Nelson A, Ranney T, Liu W, Kelliher T, Duan H, Da K. Overcoming Recalcitrance: A Review of Regeneration Methods and Challenges in Roses. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3797. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243797

Chicago/Turabian StyleNelson, Anna, Thomas Ranney, Wusheng Liu, Tim Kelliher, Hui Duan, and Kedong Da. 2025. "Overcoming Recalcitrance: A Review of Regeneration Methods and Challenges in Roses" Plants 14, no. 24: 3797. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243797

APA StyleNelson, A., Ranney, T., Liu, W., Kelliher, T., Duan, H., & Da, K. (2025). Overcoming Recalcitrance: A Review of Regeneration Methods and Challenges in Roses. Plants, 14(24), 3797. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243797