ALKBH1L Is an m6A Demethylase and Mediates PVY Infection in Nicotiana benthamiana Through m6A Modification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of AlkB Gene Family Members, Gene Domains, and Analysis of Physicochemical Properties in N. benthamiana

2.2. Expression Patterns of m6A Demethylase Candidate Genes in PVY Infected N. benthamiana Leaves

2.3. Construction of Mutant Vectors and Corresponding Phenotypic Observation

2.4. NbALKBH1L Possesses the Ability to Demethylate m6A Methylation Modifications

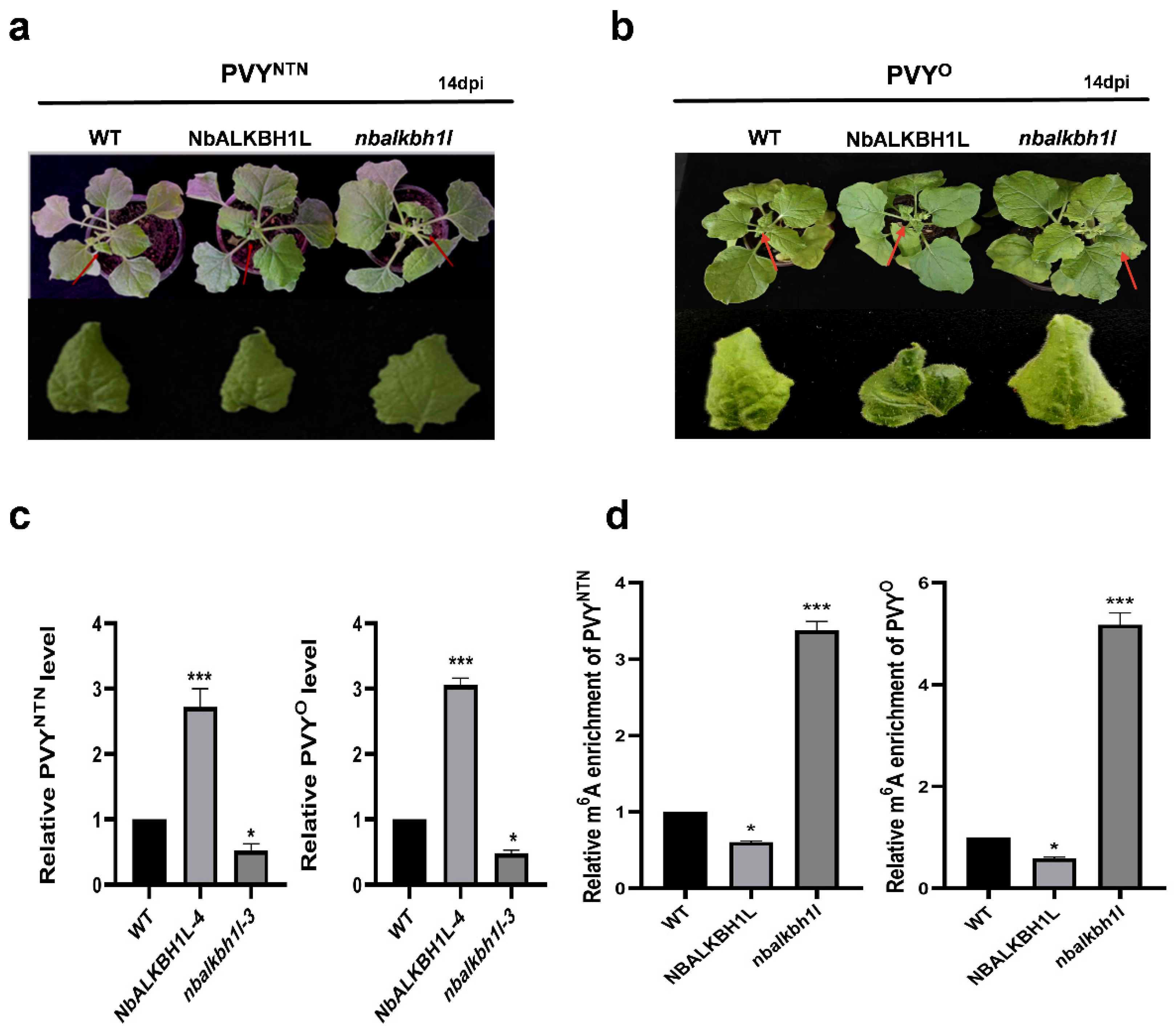

2.5. NbALKBH1L Positively Regulates PVY Infection

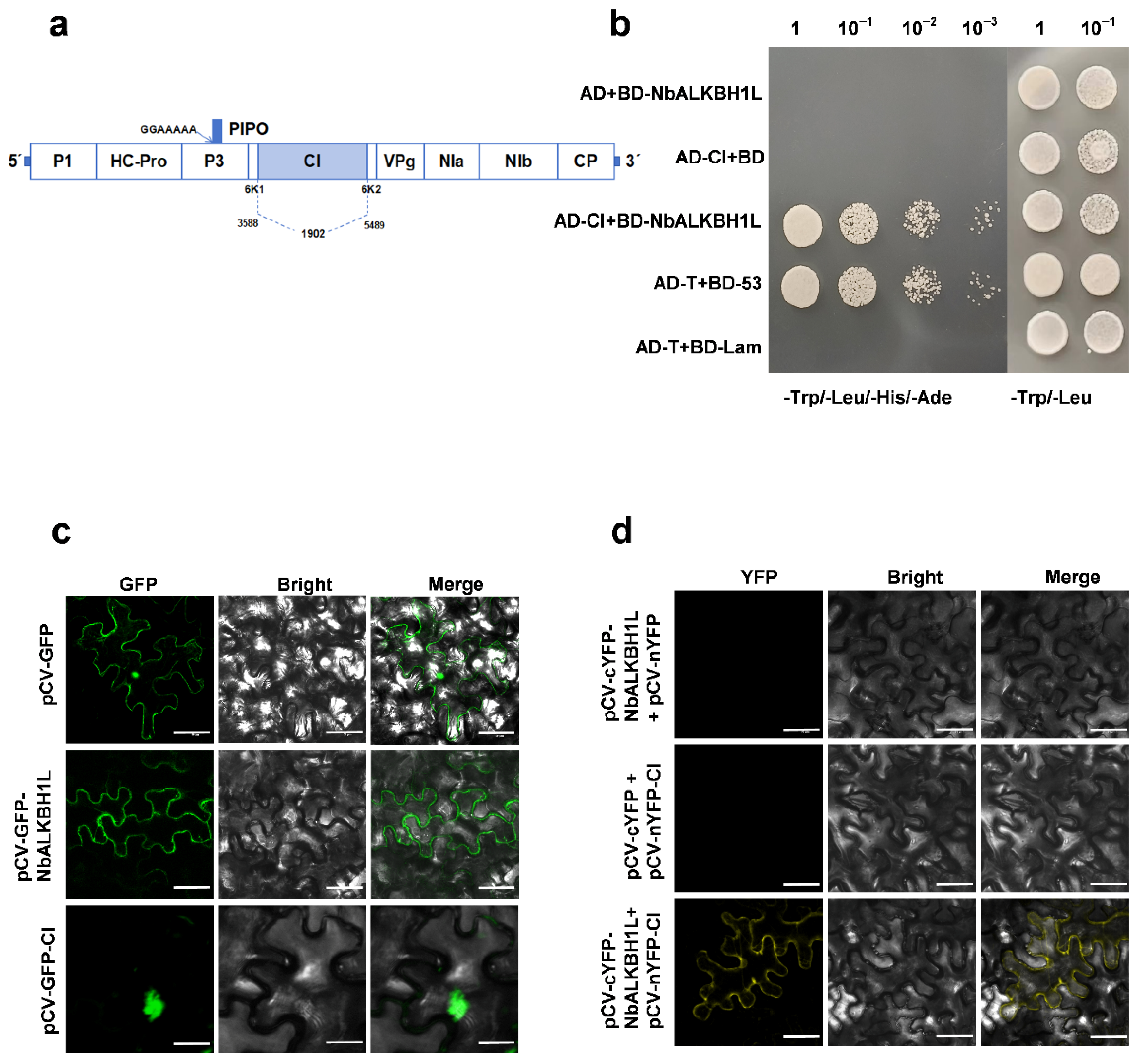

2.6. PVY CI Interacts with NbALKH1L

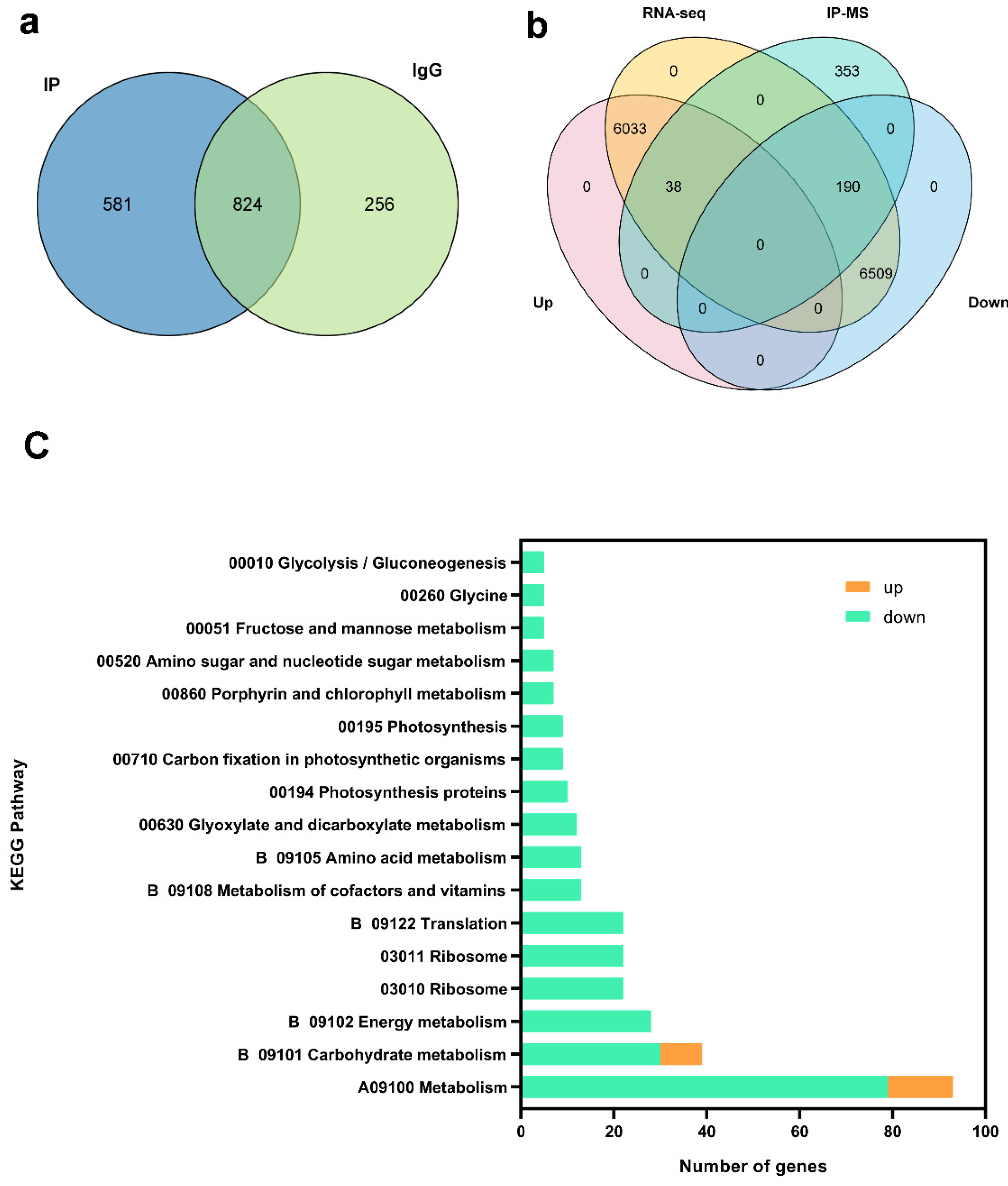

2.7. Integrated Analysis of IP-MS and RNA-Seq

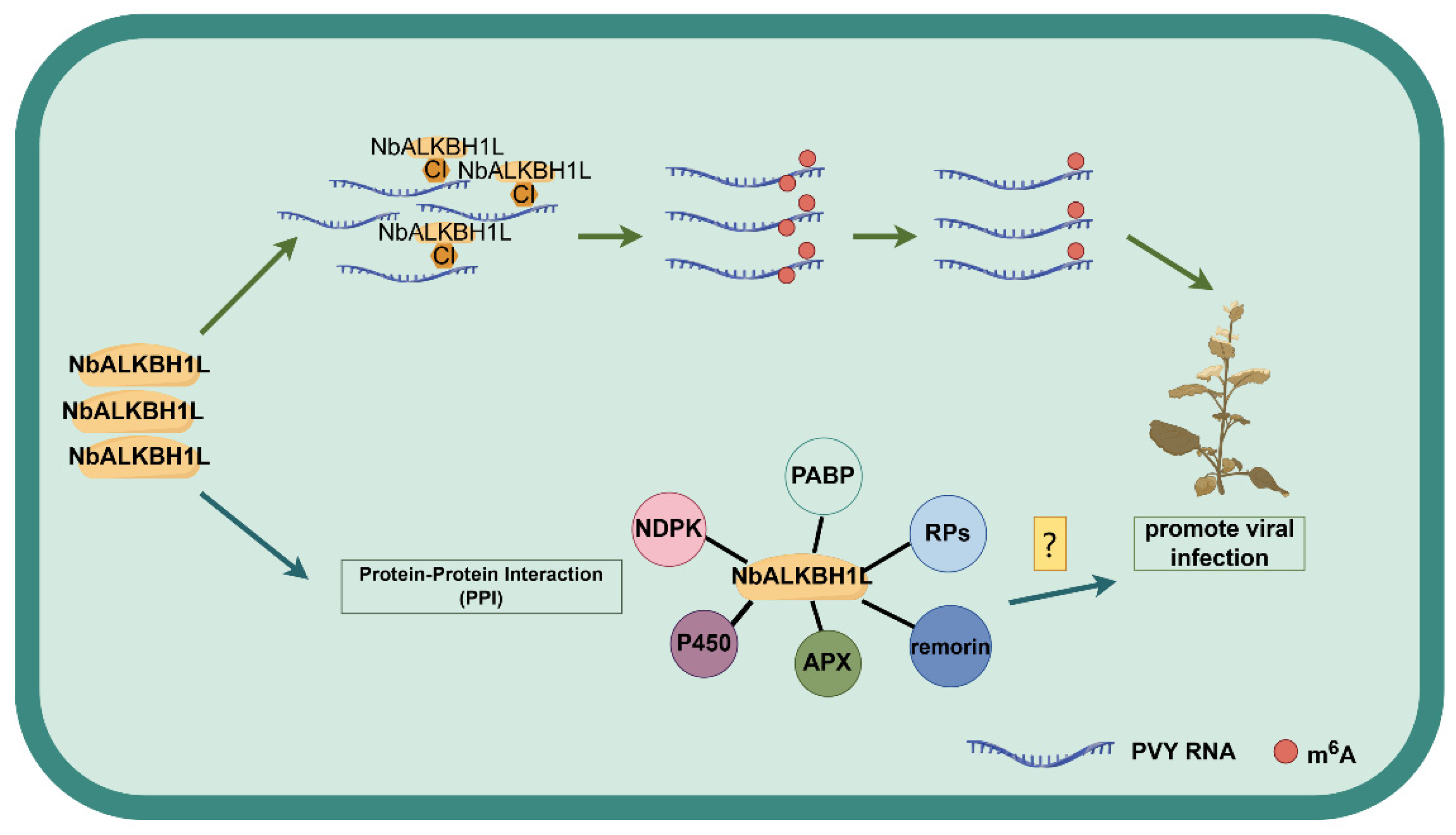

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Virus Inoculation and Sampling

4.2. Identification of AlkB Homolog (ALKB) Gene Family Members in N. benthamiana

4.3. Analysis of the Domain Structure and Physicochemical Properties of the m6A Demethylase Gene in N. benthamiana

4.4. Total RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR Analysis

4.5. Plasmid Construction

4.6. Protein Expression and Purification

4.7. Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry

4.8. Plant Transformation

4.9. Screening and Identification of Transgenic Plants

4.10. Western Blot

4.11. Dot Blot

4.12. Agrobacterium Infiltration

4.13. Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

4.14. BiFC and Subcellular Localization

4.15. m6A-IP-qPCR

4.16. Immunoprecipitation–Mass Spectrometry

4.17. RNA-Seq

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, H.; Wei, J.; He, C. Where, When, and How: Context-Dependent Functions of RNA Methylation Writers, Readers, and Erasers. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Nie, X.; Yan, Z.; Song, W. N6-methyladenosine regulatory machinery in plants: Composition, function and evolution. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1194–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Riaz, A.; Chachar, S.; Ding, Y.; Du, H.; Gu, X. Epigenetic Modifications of mRNA and DNA in Plants. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Ji, X.; Guo, X.; Ji, S. Regulatory Role of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) Methylation in RNA Processing and Human Diseases. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 2534–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motorin, Y.; Helm, M. RNA nucleotide methylation. Wiley RNA 2011, 2, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, R.; Friderici, K.; Rottman, F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 3971–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundtree, I.A.; He, C. Nuclear m6A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Trends Genet. 2016, 32, 320–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, G.; Yang, Y.; Yi, C.; Lindahl, T.; Pan, T.; Yang, Y.-G.; et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Schwartz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Ungar, L.; Osenberg, S.; Cesarkas, K.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Kupiec, M.; et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012, 485, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.D.; Saletore, Y.; Zumbo, P.; Elemento, O.; Mason, C.E.; Jaffrey, S.R. Comprehensive Analysis of mRNA Methylation Reveals Enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near Stop Codons. Cell 2012, 149, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, G.; Fu, Y.; Ji, Q.; Liu, F.; Chen, H.; He, C. Crystal structure of the RNA demethylase ALKBH5 from zebrafish. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.-F.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, W.; Hao, Y.-J.; Ping, X.-L.; Chen, Y.-S.; Wang, W.-J.; et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geula, S.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Dominissini, D.; Mansour, A.A.; Kol, N.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Hershkovitz, V.; Peer, E.; Mor, N.; Manor, Y.S.; et al. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward differentiation. Science 2015, 347, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.T.; Knop, K.; Sherwood, A.V.; Schurch, N.J.; Mackinnon, K.; Gould, P.D.; Hall, A.J.; Barton, G.J.; Simpson, G.G. Nanopore direct RNA sequencing maps the complexity of Arabidopsis mRNA processing and m6A modification. eLife 2020, 9, e49658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.-H.; Song, P.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Tang, Q.; Yu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Duan, H.-C.; Jia, G. The m6A Reader ECT2 Controls Trichome Morphology by Affecting mRNA Stability in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 968–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas-Hernández, L.; Bressendorff, S.; Hansen, M.H.; Poulsen, C.; Erdmann, S.; Brodersen, P. An m6A-YTH Module Controls Developmental Timing and Morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murik, O.; Chandran, S.A.; Nevo-Dinur, K.; Sultan, L.D.; Best, C.; Stein, Y.; Hazan, C.; Ostersetzer-Biran, O. Topologies of N6-adenosine methylation (m6A) in land plant mitochondria and their putative effects on organellar gene expression. Plant J. 2020, 101, 1269–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.-H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Peng, H.-R.; Zhou, Y.-Y.; Jia, G.-F.; He, Y. Natural Variation in RNA m6A Methylation and Its Relationship with Translational Status. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, S.S.; Bielewicz, D.; Gulanicz, T.; Bodi, Z.; Yu, X.; Anderson, S.J.; Szewc, L.; Bajczyk, M.; Dolata, J.; Grzelak, N.; et al. mRNA adenosine methylase (MTA) deposits m6A on pri-miRNAs to modulate miRNA biogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 21785–21795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glushkevich, A.; Spechenkova, N.; Fesenko, I.; Knyazev, A.; Samarskaya, V.; Kalinina, N.O.; Taliansky, M.; Love, A.J. Transcriptomic Reprogramming, Alternative Splicing and RNA Methylation in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Plants in Response to Potato Virus Y Infection. Plants 2022, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, T.D.; Lane, B.G. Wheat embryo ribonucleates. XIII. Methyl-substituted nucleoside constituents and 5′-terminal dinucleotide sequences in bulk poly(AR)-rich RNA from imbibing wheat embryos. Can. J. Biochem. 1979, 57, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S.; Li, H.; Bodi, Z.; Button, J.; Vespa, L.; Herzog, M.; Fray, R.G. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Wang, X.; Liang, X.; Huang, X.; Nawaz, M.A.; Jing, C.; Fan, Y.; Niu, J.; Wu, J.; Feng, X. Characterization of the m6A Regulatory Gene Family in Phaseolus vulgaris L. and Functional Analysis of PvMTA in Response to BCMV Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.-C.; Wei, L.-H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Lu, Z.; Chen, P.R.; He, C.; Jia, G. ALKBH10B Is an RNA N6-Methyladenosine Demethylase Affecting Arabidopsis Floral Transition. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 2995–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, S.; Yu, L.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; et al. RNA demethylation increases the yield and biomass of rice and potato plants in field trials. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MartínezPérez, M.; Aparicio, F.; ArribasHernández, L.; Tankmar, M.D.; Rennie, S.; Bülow, S.v.; LindorffLarsen, K.; Brodersen, P.; Pallas, V. Plant YTHDF proteins are direct effectors of antiviral immunity against an N6-methyladenosine-containing RNA virus. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e113378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Tang, Q.; Song, P.; Tian, E.; Yang, J.; Jia, G. The m6A reader ECT8 is an abiotic stress sensor that accelerates mRNA decay in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 2908–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.X.; Lang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, C.G. A mutually antagonistic mechanism mediated by RNA m6A modification in plant-virus interactions. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 10378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InoueNagata, A.K.; Jordan, R.; Kreuze, J.; Li, F.; LópezMoya, J.J.; Mäkinen, K.; Ohshima, K.; Wylie, S.J.; Consortium, I.R. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Potyviridae 2022. J. Gen. Virol. 2022, 103, 001738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasin, F.; Daròs, J.; Tzanetakis, I.E. Proteome expansion in the Potyviridae evolutionary radiation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 46, fuac011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.H.; Adams, M.J.; Barnett, O.W.; Brunt, A.A.; Hammond, J.; Hill, J.H.; Jordan, R.L.; Vetten, H.J. Family: Potyviridae. In Virus Taxonomy: Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; ICTV, Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 819–841. [Google Scholar]

- Moury, B.; Morel, C.; Johansen, E.; Jacquemond, M. Evidence for diversifying selection in Potato virus Y and in the coat protein of other potyviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.P.; Valkonen, J.P.T.; Gray, S.M.; Boonham, N.; Jones, R.A.C.; Kerlan, C.; Schubert, J. Discussion paper: The naming of Potato virus Y strains infecting potato. Arch. Virol. 2008, 153, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanigliulo, A.; Comes, S.; Pacella, R.; Harrach, B.; Martin, D.P.; Crescenzi, A. Characterisation of Potato virus Y nnp strain inducing veinal necrosis in pepper: A naturally occurring recombinant strain of PVY. Arch. Virol. 2005, 150, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, B.Y.-W.; Miller, W.A.; Atkins, J.F.; Firth, A.E. An overlapping essential gene in the Potyviridae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5897–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, B.A.; Flores, V.; Marholz, G. Effect of Potato virus Y on growth, yield, and chemical composition of flue-cured tobacco in Chile. Plant Dis. 1984, 68, 884–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.A.; Jenner, C.E. Turnip mosaic virus and the quest for durable resistance. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 3, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenouille, J.; Vassilakos, N.; Moury, B. Potato virus Y: A major crop pathogen that has provided major insights into the evolution of viral pathogenicity. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Wei, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wei, X.; Wang, H.; Pasin, F.; Zhao, M. AlkB RNA demethylase homologues and N6-methyladenosine are involved in Potyvirus infection. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez, M.; Aparicio, F.; López-Gresa, M.P.; Bellés, J.M.; Sánchez-Navarro, J.A.; Pallás, V. Arabidopsis m6A demethylase activity modulates viral infection of a plant virus and the m6A abundance in its genomic RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10755–10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Srivastava, S.; Rahman, M.H.; Kav, N.N.V.; Hotte, N.; Deyholos, M.K.; Strelkov, S.E. Proteome-level changes in the roots of Brassica napus as a result of Plasmodiophora brassicae infection. Plant Sci. 2008, 174, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Biswas, A.; Dey, S.; Bhattacharjee, T.; Chakrabarty, S. Cytochrome P450 Gene Families: Role in Plant Secondary Metabolites Production and Plant Defense. J. Xenobiot. 2023, 13, 402–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; Cao, H.; Pan, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, L.; Huang, D. Phosphatidylcholine Transfer Protein OsPCTP Interacts with Ascorbate Peroxidase OsAPX8 to Regulate Bacterial Blight Resistance in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.-U.; Lee, I.-G.; Ko, Y.-J.; Oh, D.-K. Microbial Synthesis of Linoleate 9 S-Lipoxygenase derived Plant C18 Oxylipins from C18 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 3209–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Greene, G.H.; Xu, G.; Dong, X. PABP/purine-rich motif as an initiation module for cap-independent translation in pattern-triggered immunity. Cell 2022, 185, 3186–3200.e3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajamäki, M.-L.; Xi, D.; Sikorskaite-Gudziuniene, S.; Valkonen, J.P.T.; Whitham, S.A. Differential Requirement of the Ribosomal Protein S6 and Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase for Plant-Virus Accumulation and Interaction of S6 Kinase with Potyviral VPg. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2017, 30, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helderman, T.A.; Deurhof, L.; Bertran, A.; Richard, M.M.S.; Kormelink, R.; Prins, M.; Joosten, M.H.A.J.; Burg, H.A.v.d. Members of the ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6) family act as pro-viral factor for tomato spotted wilt orthotospovirus infectivity in Nicotiana benthamiana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffaele, S.; Bayer, E.; Lafarge, D.; Cluzet, S.p.; Retana, S.G.; Boubekeur, T.; Leborgne-Castel, N.; Carde, J.-P.; Lherminier, J.; Noirot, E.; et al. Remorin, a solanaceae protein resident in membrane rafts and plasmodesmata, impairs potato virus X movement. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 1541–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Ge, X.; Song, F. A rice serine carboxypeptidase-like gene OsBISCPL1 is involved in regulation of defense responses against biotic and oxidative stress. Gene 2008, 420, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, J.; Sousa, S.M.; Figueiredo, A. Subtilisin-like proteases in plant defence: The past, the present and beyond. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Song, F. Ectopic expression of a rice protein phosphatase 2C gene OsBIPP2C2 in tobacco improves disease resistance. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Wan, S.; Lin, F.; Xu, H. Comparison of Glyphosate-Degradation Ability of Aldo-Keto Reductase (AKR4) Proteins in Maize, Soybean and Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sappah, A.H.E.; Li, J.; Yan, K.; Zhu, C.; Huang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tarabily, K.A.E.; AbuQamar, S.F. Fibrillin gene family and its role in plant growth, development, and abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1453974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Jia, G.; Pang, X.; Wang, R.N.; Wang, X.; Li, C.J.; Smemo, S.; Dai, Q.; Bailey, K.A.; Nobrega, M.A.; et al. FTO-mediated formation of N6-hydroxymethyladenosine and N6-formyladenosine in mammalian RNA. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Dahl, J.A.; Niu, Y.; Fedorcsak, P.; Huang, C.-M.; Li, C.J.; Vågbø, C.B.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.-L.; Song, S.-H.; et al. ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Lei, D.; Yang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Cai, Z.; Zhu, S.; Wan, J.; et al. OsALKBH9-mediated m6A demethylation regulates tapetal PCD and pollen exine accumulation in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2410–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, L.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, M. Transcriptome-wide N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methylation in watermelon under CGMMV infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Tian, S.; Qin, G. RNA methylomes reveal the m6A-mediated regulation of DNA demethylase gene SlDML2 in tomato fruit ripening. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Pan, F.; Jia, M.; Pott, D.M.; He, H.; Shan, H.; Durán, R.L.; Wang, A.; Zhou, X.; Li, F. RNA modifications in plant biotic interactions. Plant Commun. 2024, 6, 101232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Ye, J.; Wei, T.; Li, Z.; Tao, X.; Cui, F.; Wang, X.; et al. Plant virology in the 21st century in China: Recent advances and future directions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 579–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Ge, L.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Li, F. Pepino mosaic virus antagonizes plant m6A modification by promoting the autophagic degradation of the m6A writer HAKAI. aBIOTECH 2023, 4, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shi, C.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Feng, H.; Liu, P.; Guo, J.; Lu, Q.; et al. N6-methyladenosine RNA modification promotes viral genomic RNA stability and infection. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Zhang, C.; Hong, J.; Xiong, R.; Kasschau, K.D.; Zhou, X.; Carrington, J.C.; Wang, A. Formation of complexes at plasmodesmata for potyvirus intercellular movement is mediated by the viral protein P3N-PIPO. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. Cell-to-cell movement of plant viruses via plasmodesmata: A current perspective on potyviruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021, 48, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Laín, S.; García, J.A. RNA helicase activity of the plum pox potyvirus CI protein expressed in Escherichia coli. Mapping of an RNA binding domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Huang, T.-S.; McNeil, J.; Laliberté, J.-F.; Hong, J.; Nelson, R.S.; Wang, A. Sequential recruitment of the endoplasmic reticulum and chloroplasts for plant potyvirus replication. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Cui, X.; Chen, H.; Renaud, J.B.; Yu, K.; Chen, X.; Wang, A. Dynamin-Like Proteins of Endocytosis in Plants Are Coopted by Potyviruses To Enhance Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01320-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Cui, X.; Dai, Z.; He, R.; Li, Y.; Yu, K.; Bernards, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, A. A plant RNA virus hijacks endocytic proteins to establish its infection in plants. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 101, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, X.; Molen, T.A. Host recovery and reduced virus level in the upper leaves after Potato virus Y infection occur in tobacco and tomato but not in potato plants. Viruses 2015, 7, 680–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D265–D268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artimo, P.; Jonnalagedda, M.; Arnold, K.; Baratin, D.; Csardi, G.; Castro, E.d.; Duvaud, S.; Flegel, V.; Fortier, A.; Gasteiger, E.; et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W597–W603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, G.C.; Flores-Vergara, M.A.; Krasynanski, S.; Kumar, S.; Thompson, W.F. A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissues using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2320–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, S.; Soares, F.; Ahmed, M.; Guo, H.; Wang, M.; Hua, J.T.; Guan, J.; Moran, M.F.; et al. Refined RIP-seq protocol for epitranscriptome analysis with low input materials. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2006092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhuang, X.; Dong, Z.; Xu, K.; Chen, X.; Liu, F.; He, Z. The dynamics of N6-methyladenine RNA modification in interactions between rice and plant viruses. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, J.; Sun, S.; Yuan, J.; Dong, L.; Wang, X.; Jing, C.; Nawaz, M.A.; Tang, R.; Cao, H.; Nie, B.; et al. ALKBH1L Is an m6A Demethylase and Mediates PVY Infection in Nicotiana benthamiana Through m6A Modification. Plants 2025, 14, 3796. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243796

Zhou J, Sun S, Yuan J, Dong L, Wang X, Jing C, Nawaz MA, Tang R, Cao H, Nie B, et al. ALKBH1L Is an m6A Demethylase and Mediates PVY Infection in Nicotiana benthamiana Through m6A Modification. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3796. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243796

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Jue, Shuocong Sun, Jingtao Yuan, Li Dong, Xinhua Wang, Chenchen Jing, Muhammad Amjad Nawaz, Ruimin Tang, Hui Cao, Bihua Nie, and et al. 2025. "ALKBH1L Is an m6A Demethylase and Mediates PVY Infection in Nicotiana benthamiana Through m6A Modification" Plants 14, no. 24: 3796. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243796

APA StyleZhou, J., Sun, S., Yuan, J., Dong, L., Wang, X., Jing, C., Nawaz, M. A., Tang, R., Cao, H., Nie, B., & Feng, X. (2025). ALKBH1L Is an m6A Demethylase and Mediates PVY Infection in Nicotiana benthamiana Through m6A Modification. Plants, 14(24), 3796. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243796