Sustainable Management of Invasive Algal Waste (Caulerpa prolifera): Biomass Compost for Nitrogen Reduction in Vulnerable Coastal Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

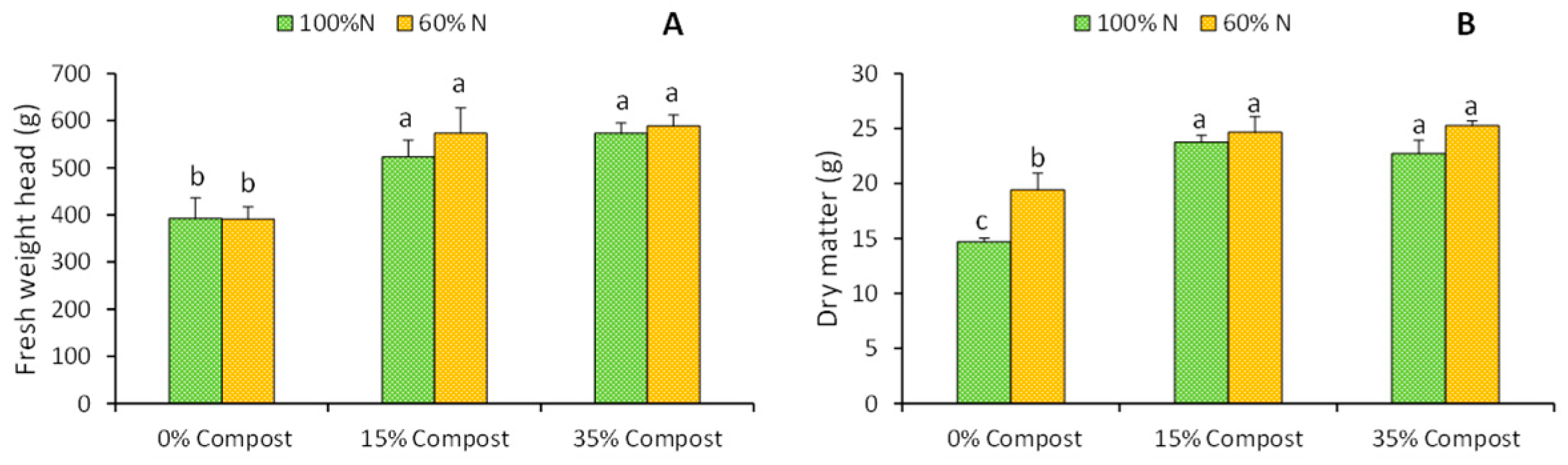

2.1. Biomass

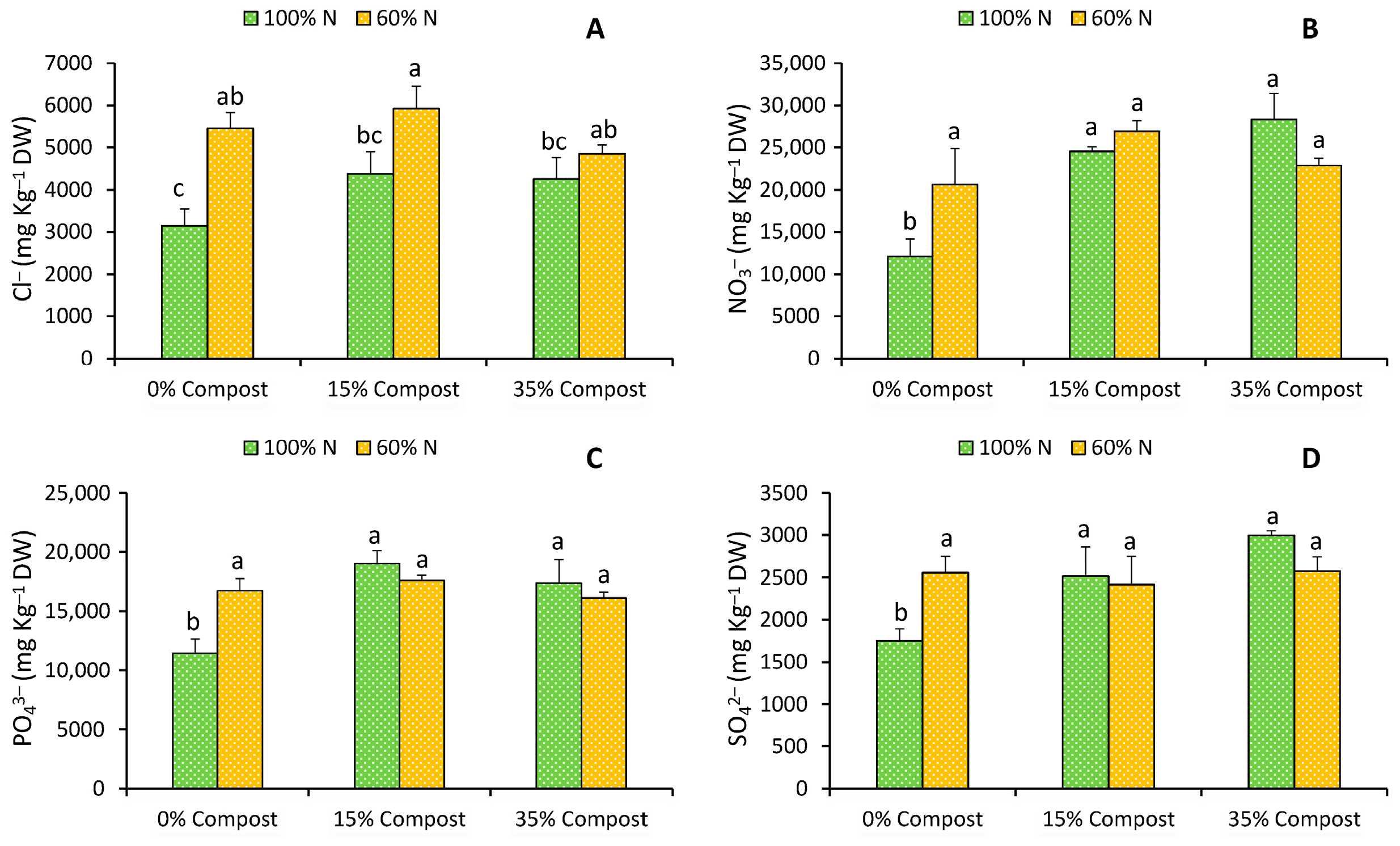

2.2. Mineral Content

2.3. Free Amino Acids

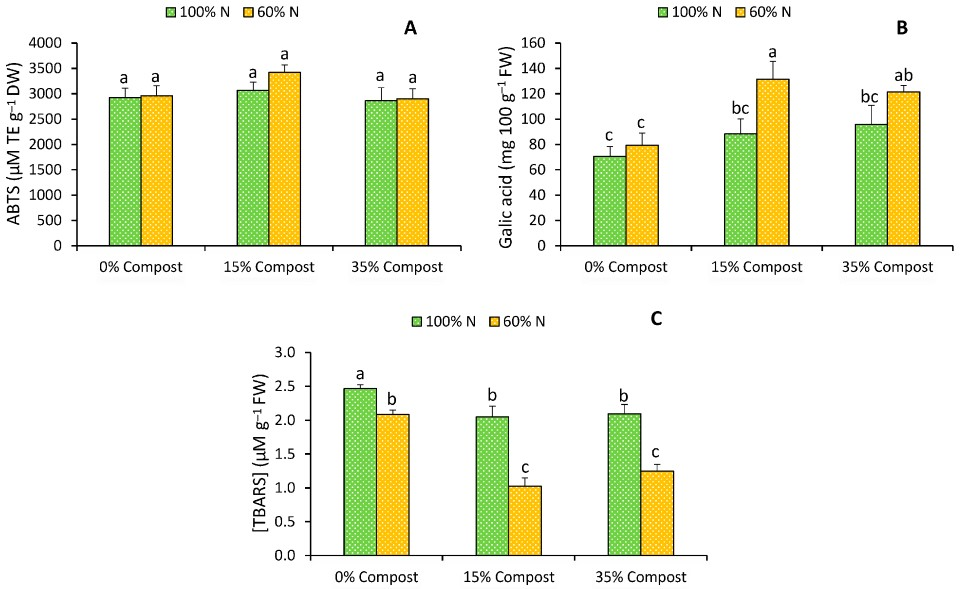

2.4. Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolic Compounds and Lipid Peroxidation

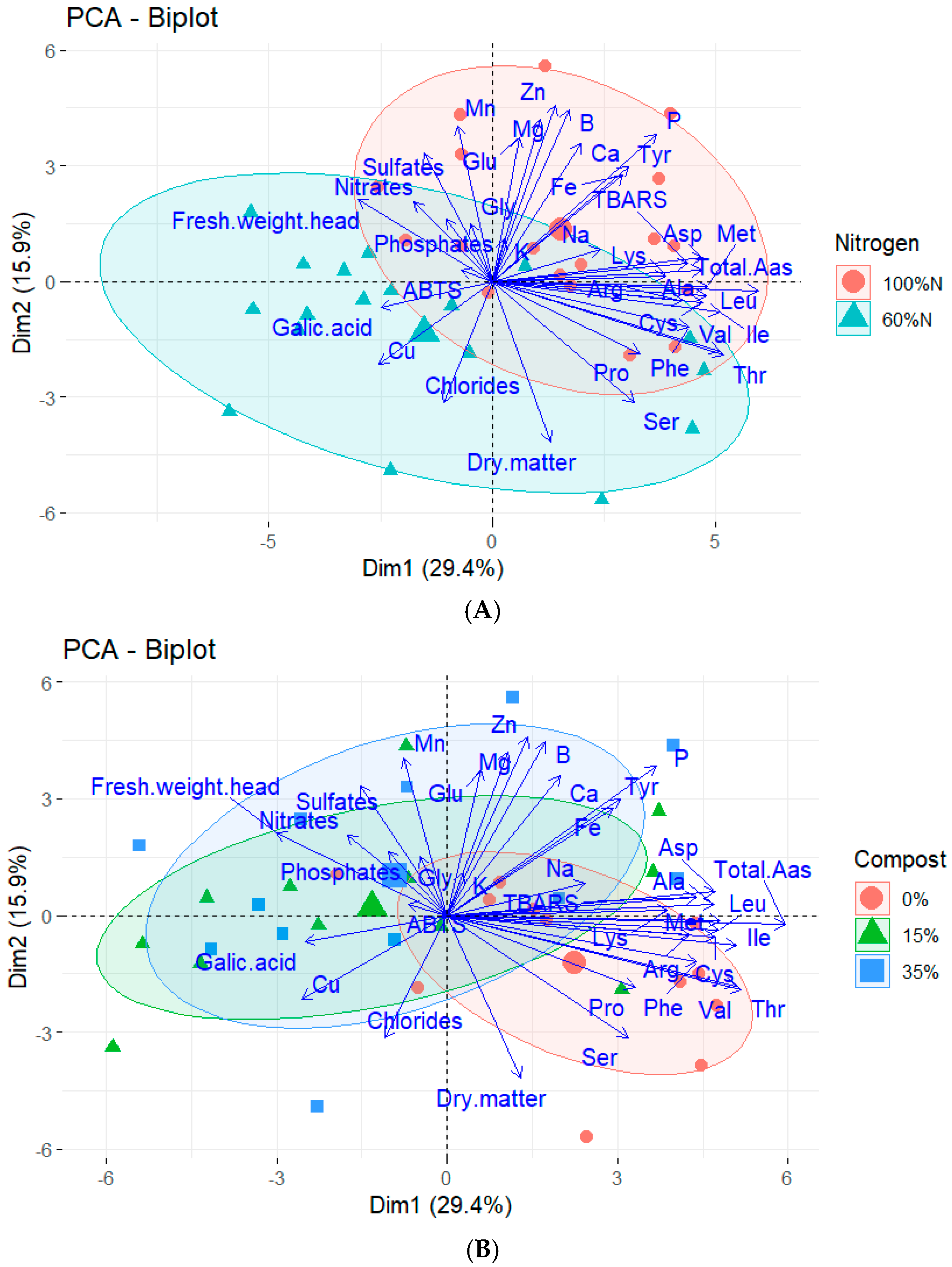

2.5. Principal Component Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

- (1)

- 100% N + 0% Compost

- (2)

- 100% N + 15% Compost

- (3)

- 100% N + 35% Compost

- (4)

- 60% N + 0% Compost

- (5)

- 60% N + 15% Compost

- (6)

- 60% N + 35% Compost

3.2. Method of Composting

3.3. Biomass

3.4. Mineral Content

3.5. Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolic Compounds and Lipid Peroxidation

3.6. Free Amino Acids

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ballester Sabater, R. El Componente Vegetal en los Humedales de La Región de Murcia: Catalogación, Evaluación de la Rareza y Propuestas de Medidas para su Conservación; Novograf, S.A.: Murcia, Spain, 2003; ISBN 84-688-2563-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A.; Morkune, R.; Marcos, C.; Pérez-Ruzafa, I.M.; Razinkovas-Baziukas, A. Can an Oligotrophic Coastal Lagoon Support High Biological Productivity? Sources and Pathways of Primary Production. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 153, 104824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero, M.C.; Collado-González, J.; Otálora, G.; González, Y.; Amor, F.M. Agro-Physiological Performance of Iceberg Le Tt Uce (Lactuca sativa L.) Cultivated on Substrates Amended with the Invasive Algae Caulerpa prolifera from the Mar Menor. Phycology 2025, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Xie, X. Effects of Different Composting Methods on Enteromorpha: Maturity, Nutrients, and Organic Carbon Transformation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibilisco, P.E.; Lancelotti, J.L.; Negrin, V.L.; Idaszkin, Y.L. Composting of seaweed waste: Evaluation on the growth of Sarcocornia perennis. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 274, 111193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madejón, E.; Panettieri, M.; Madejón, P.; Pérez-de-Mora, A. Composting as Sustainable Managing Option for Seaweed Blooms on Recreational Beaches. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2022, 13, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, I.; Tuhy, L.; Chojnacka, K.W. Co-Composting of Algae and Effect of the Compost on Germination and Growth of Lepidium sativum. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 25, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabti, E.; Jha, B.; Hartmann, A. Impact of seaweeds on agricultural crop production as biofertilizer. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 14, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Council Directive 91/676/EEC of 12 December 1991 Concerning the Protection of Waters Against Pollution Caused by Nitrates from Agricultural Sources. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1991, 375, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto-Ley 14/2020, de 7 de Agosto, de Medidas Urgentes para Garantizar la Sostenibilidad Ambiental en el Entorno del Mar Menor. Boletín Of. Estado 2020, 221, 70878–70952. [Google Scholar]

- Ammaturo, C.; Pacheco, D.; Cotas, J.; Formisano, L.; Ciriello, M.; Pereira, L.; Bahcevandziev, K. Use of Chlorella vulgaris and Ulva lactuca as Biostimulant on Lettuce. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, E.E.; Aioub, A.A.A.; Elesawy, A.E.; Karkour, A.M.; Mouhamed, M.S.; Amer, A.A.; EL-Shershaby, N.A. Algae as Bio-Fertilizers: Between Current Situation and Future Prospective: The Role of Algae as a Bio-Fertilizer in Serving of Ecosystem. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 3083–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulant properties of seaweed extracts in plants: Implications towards sustainable crop production. Plants 2021, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz Ferreira, R.L.; De Mello Prado, R.; De Souza Junior, J.P.; Gratão, P.L.; Tezotto, T.; Cruz, F.J.R. Oxidative Stress, Nutritional Disorders, and Gas Exchange in Lettuce Plants Subjected to Two Selenium Sources. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Livestock Products. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- MAPA. Anuario de Estadística 2023. Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/estadistica/pags/anuario/2023/global%202023/ANUARIO_2023.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Tsouvaltzis, P.; Kasampali, D.S.; Aktsoglou, D.C.; Barbayiannis, N.; Siomos, A.S. Effect of reduced nitrogen and supplemented amino acids nutrient solution on the nutritional quality of baby green and red lettuce grown in a floating system. Agronomy 2020, 10, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, I.G.; Durnford, J.; Lynn, J.; McClement, S.; Hand, P.; Pink, D. The influence of genetic variation and nitrogen source on nitrate accumulation and iso-osmotic regulation by lettuce. Plant Soil 2012, 352, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Antón, A.A.; Zamora-Natera, J.F.; Zarazúa-Villaseñor, P.; Santacruz-Ruvalcaba, F.; Sánchez-Hernández, C.V.; Águila Alcántara, E.; Torres-Morán, M.I.; Velasco-Ramírez, A.P.; Hernández-Herrera, R.M. Application of Seaweed Generates Changes in the Substrate and Stimulates the Growth of Tomato Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Boukhari, M.E.M.; Barakate, M.; Bouhia, Y.; Lyamlouli, K. Trends in seaweed extract based biostimulants: Manufacturing process and beneficial effect on soil-plant systems. Plants 2020, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, I.B.; Ledezma, A.K.D.; Montaño, E.M.; Leyva, J.A.S.; Carrera, E.; Ruiz, I.O. Identification and quantification of plant growth regulators and antioxidant compounds in aqueous extracts of Padina durvillaei and Ulva lactuca. Agronomy 2020, 10, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battacharyya, D.; Babgohari, M.Z.; Rathor, P.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed extracts as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhouna, D.; Kies, F.; Elegbede, I.; Matemilola, S.; Zorriehzahra, J.; Hussein, E.K. Use of two green algae Ulva lactuca and Ulva intestinalis as bio-fertilizers. Sustain. Agri Food Environ. Res. 2021, 9, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Solangi, F.; Azeem, S.; Bodlah, M.A.; Zaheer, M.S.; Niaz, Y.; Ashraf, M.; Abid, M.; Gul, H.; et al. Impact of amino acid supplementation on hydroponic lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) growth and nutrient content. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salahas, G.; Papasavvas, A.; Giannakopoulos, E.; Tselios, T.; Konstantopoulou, H.; Savvas, D. Impact of Nitrogen Deficiency on Biomass Production, Leaf Gas Exchange, and Betacyanin and Total Phenol Concentrations in Red Beet (Beta vulgaris L. ssp. vulgaris) Plants. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2011, 76, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, O.; Bakare, O.O.; Daniel, A.I.; Gokul, A.; Beukes, D.R.; Fadaka, A.O.; Keyster, M.; Klein, A. Seaweed-Derived Phenolic Compounds in Growth Promotion and Stress Alleviation in Plants. Life 2022, 12, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahabi, S.; Daoudi, N.E.; Chebaibi, M.; Mssillou, I.; Rahhou, I.; Bnouham, M.; Hammouti, B.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Ayerdi Gotor, A.; Rhazi, L.; et al. A Comparative Study of the Phytochemical Composition, Antioxidant Properties, and In Vitro Anti-Diabetic Efficacy of Different Extracts of Caulerpa prolifera. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Debnath, P.; Singh, S.; Kumar, N. An overview of plant phenolics and their involvement in abiotic stress tolerance. Stresses 2023, 3, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, I.; Guesmi, F.; Kharbech, O.; Hfaiedh, N.; Djebali, W. Gallic acid improves the antioxidant ability against cadmium toxicity: Impact on leaf lipid composition of sunflower (Helianthus annuus) seedlings. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 210, 111906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaid, A.; Mohammad, F.; Wani, S.H.; Siddique, K.M.H. Salicylic acid enhances nickel stress tolerance by up-regulating antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems in mustard plants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 180, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero, M.C.; Gómez-Candón, D.; López-Maestresalas, A.; Collado-González, J.; Otálora, G.; del Amor, F.M. Cost-effective multispectral imaging system for detecting nitrogen over-fertilization under different temperatures in greenhouse sweet pepper plants. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahkonen, M.P.; Hopia, A.I.; Vuorela, H.J.; Rauha, J.P.; Pihlaja, K.; Kujala, T.S.; Heinonen, M. Antioxidant activity of plant extracts containing phenolic compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3954–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in Isolated Chloroplasts: I. Kinetics and Stoichiometry of Fatty Acid Peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrasse, K.B.; Gallego, S.M.; Tomaro, M.L. Aluminium stress affects nitrogen fixation and assimilation in soybean (Glycine max L.). Plant Growth Regul. 2006, 48, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-González, J.; Piñero, M.; Otálora, G.; López-Marín, J.; Del Amor Saavedra, F.M. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria as Affected by N Availability as a Suitable Strategy to Enhance the Nutritional Composition of Lamb’s Lettuce Affected by Global Warming. Food Chem. 2023, 426, 136559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters. UPLC Amino Acid Analysis Solution; Waters Corporation: Milford, MA USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| N | Compost | P | K | Ca | Mg | Na | B | Mn | Fe | Zn | Cu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (C) | g Kg−1 DW | mg Kg−1 DW | ||||||||||

| 100% | Control | 7.31 ± 0.04 ab | 41.74 ± 1.45 a | 2.26 ± 0.19 a | 1.41 ± 0.02 ab | 1.48 ± 0.09 a | 16.05 ± 0.37 b | 6.40 ± 0.41 c | 104.70 ± 2.20 b | 55.78 ± 2.03 b | 4.07 ± 0.24 b | |

| 15% C | 7.62 ± 0.03 a | 40.26 ± 0.36 a | 1.66 ± 0.23 ab | 1.46 ± 0.14 a | 1.18 ± 0.09 bc | 16.13 ± 0.81 b | 10.93 ± 1.51 ab | 116.33 ± 4.37 a | 71.20 ± 2.41 a | 3.22 ± 0.58 b | ||

| 35% C | 7.59 ± 0.18 a | 44.40 ± 1.48 a | 2.25 ± 0.20 a | 1.40 ± 0.15 ab | 1.26 ± 0.08 abc | 18.33 ± 1.01 a | 13.20 ± 0.53 a | 85.38 ± 3.08 c | 75.05 ± 5.63 a | 3.29 ± 0.58 b | ||

| 60% | Control | 7.14 ± 0.15 b | 43.10 ± 1.88 a | 1.77 ± 0.25 ab | 1.25 ± 0.09 ab | 1.41 ± 0.07 ab | 15.66 ± 0.34 b | 6.07 ± 1.26 c | 86.03 ± 2.44 c | 54.64 ± 3.03 b | 3.97 ± 0.12 b | |

| 15% C | 6.77 ± 0.04 c | 40.22 ± 1.36 a | 1.49 ± 0.43 ab | 1.32 ± 0.06 ab | 1.10 ± 0.12 c | 14.10 ± 0.38 b | 6.85 ± 0.14 c | 70.70 c ± 8.50 d | 53.45 ± 0.26 b | 5.67 ± 0.08 a | ||

| 35% C | 6.70 ± 0.11 c | 40.85 ± 1.11 a | 1.32 ± 0.13 b | 1.09 ± 0.18 b | 1.08 ± 0.08 c | 14.93 ± 1.05 b | 9.60 ± 1.83 bc | 80.70 ± 2.49 cd | 59.93 ± 3.53 b | 4.17 ± 0.18 b | ||

| [N] | Compost | Ser | Arg | Gly | Asp | Glu | Thr | Ala | Pro | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (C) | (µmol L−1) | |||||||||

| 100% | Control | 141.0 ± 13.9 b | 97.5 ± 28.0 ab | 14.3 ± 0.7 ab | 47.4 ± 5.2 ab | 41.6 ± 4.5 a | 110.0 ± 9.2 ab | 125.4 ± 15.6 ab | 26.1 ± 2.9 ab | |

| 15% C | 129.1 ± 14.7 b | 125.2 ± 29.3 ab | 9.2 ± 1.4 bc | 49.5 ± 3.1 a | 37.4 ± 5.0 a | 97.4 ± 8.0 bc | 180.6 ± 11.2 a | 20.3 ± 3.8 b | ||

| 35% C | 106.7 ± 13.9 b | 104.6 ± 21.0 ab | 19.4 ± 3.1 a | 31.4 ± 4.5 c | 39.1 ± 4.8 a | 91.9 ± 16.7 bc | 137.8 ± 30.0 ab | 22.0 ± 3.4 b | ||

| 60% | Control | 193.0 ± 15.3 a | 183.9 ± 43.2 a | 7.1 ± 0.9 c | 37.4 ± 1.5 bc | 14.8 ± 3.3 b | 141.4 ± 17.6 a | 161.3 ± 17.3 a | 38.4 ± 8.1 a | |

| 15% C | 128.8 ± 19.5 b | 78.9 ± 35.1 b | 18.0 ± 3.6 a | 12.3 ± 2.0 d | 23.6 ± 5.2 b | 40.9 ± 9.3 d | 56.8 ± 4.2 c | 24.3 ± 5.0 b | ||

| 35% C | 107.8 ± 7.1 b | 56.2 ± 8.2 b | 10.2 ± 2.2 bc | 15.7 ± 2.8 d | 20.9 ± 2.3 b | 69.7 ± 7.6 cd | 87.0 ± 16.0 bc | 14.8 ± 2.2 b | ||

| [N] | Compost | Cys | Lys | Tyr | Met | Val | Ile | Leu | Phe | Total |

| (C) | (µmol L−1) | |||||||||

| 100% | Control | 10.9 ± 0.3 a | 14.1 ± 1.4 b | 144.1 ± 26.5 b | 5.8 ± 0.6 b | 61.9 ± 7.8 b | 81.0 ± 9.7 ab | 71.0 ± 7.0 a | 55.0 ± 4.1 ab | 1044.6 ± 98.0 a |

| 15% C | 11.4 ± 0.3 a | 22.3 ± 3.7 b | 149.5 ± 16.4 b | 8.8 ± 0.6 a | 67.2 ± 11.0 b | 92.6 ± 17.9 a | 68.9 ± 7.1 a | 53.7 ± 3.6 ab | 1120.9 ± 102.4 a | |

| 35% C | 11.5 ± 0.2 a | 30.1 ± 2.5 a | 230.5 ± 22.2 a | 8.6 ± 1.3 a | 63.1 ± 5.0 b | 81.2 ± 14.4 ab | 73.9 ± 10.1 a | 55.1 ± 6.3 ab | 1106.6 ± 116.3 a | |

| 60% | Control | 11.4 ± 0.3 a | 24.8 ± 4.2 a | 87.8 ± 8.0 c | 8.8 ± 0.6 a | 108.1 ± 11.9 a | 90.4 ± 8.4 a | 77.0 ± 5.1 a | 68.6 ± 8.7 a | 1254.3 ± 91.7 a |

| 15% C | 9.6 ± 0.1 b | 5.1 ± 1.0 c | 77.2 ± 15.0 c | 2.9 ± 0.4 c | 24.1 ± 5.3 c | 48.7 ± 6.4 b | 51.8 ± 10.6 a | 49.7 ± 3.9 b | 635.4 ± 75.3 b | |

| 35% C | 10.1 ± 0.2 b | 5.1 ± 1.0 c | 105.5 ± 9.5 c | 5.4 ± 0.5 b | 47.9 ± 6.3 b | 55.7 ± 14.1 ab | 61.2 ± 6.5 a | 48.6 ± 2.3 b | 721.7 ± 73.7 b | |

| Parameters | Compost | Coconut Fiber |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.49 ± 0.04 | 6.3 ± 0.1 |

| EC (µS/cm) | 1670 ± 100 | 225 ± 15 |

| Organic matter | 59.20 ± 0.50 | 80% ± 0.1 |

| %C | 28.7 | 40 |

| %N | 2.1 | 0.5 |

| C/N | 13.5 | 80 |

| Concentrations (mg/kg) | ||

| As | 7.42 ± 0.36 | Trace levels |

| Zn | 250.67 ± 7.16 | 9.1 |

| Pb | 304.12 ± 5.76 | Trace levels |

| Cd | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 1.06 |

| Cu | 9.55 ± 0.84 | 5.88 |

| P | 956.55 ± 49.25 | 844.00 |

| Mn | 970.99 ± 29.24 | 18.37 |

| Ca | 3054.74 ± 30.28 | 2947.33 |

| Na | 903.44 ± 90.68 | 1387.00 |

| K | 1291.57 ± 31.12 | 6308.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piñero, M.C.; García Delgado, C.; López Rayo, S.; Collado-González, J.; Otálora, G.; del Amor, F.M. Sustainable Management of Invasive Algal Waste (Caulerpa prolifera): Biomass Compost for Nitrogen Reduction in Vulnerable Coastal Area. Plants 2025, 14, 3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243778

Piñero MC, García Delgado C, López Rayo S, Collado-González J, Otálora G, del Amor FM. Sustainable Management of Invasive Algal Waste (Caulerpa prolifera): Biomass Compost for Nitrogen Reduction in Vulnerable Coastal Area. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243778

Chicago/Turabian StylePiñero, María Carmen, Carlos García Delgado, Sandra López Rayo, Jacinta Collado-González, Ginés Otálora, and Francisco M. del Amor. 2025. "Sustainable Management of Invasive Algal Waste (Caulerpa prolifera): Biomass Compost for Nitrogen Reduction in Vulnerable Coastal Area" Plants 14, no. 24: 3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243778

APA StylePiñero, M. C., García Delgado, C., López Rayo, S., Collado-González, J., Otálora, G., & del Amor, F. M. (2025). Sustainable Management of Invasive Algal Waste (Caulerpa prolifera): Biomass Compost for Nitrogen Reduction in Vulnerable Coastal Area. Plants, 14(24), 3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243778