Diversity and Biocontrol Potential of Fungi Associated with Cyst Nematodes and Soils in Swiss Potato Agroecosystems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Fungal Diversity Associated with Cyst Nematodes and Soil Samples

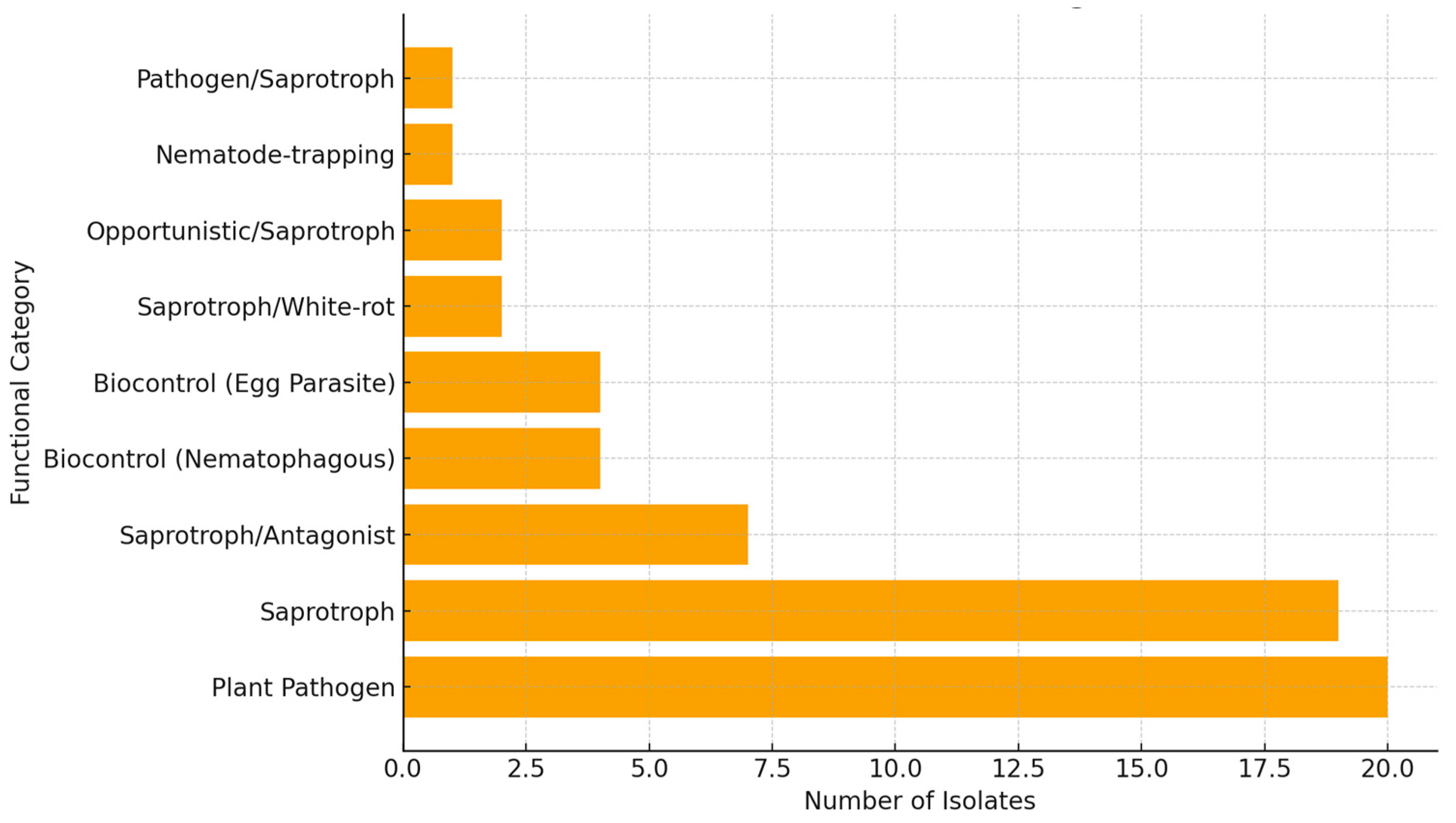

2.2. Functional Insights and Biocontrol Potential

2.3. In Vitro Evaluation of Fungal Isolates Against Meloidogyne incognita

2.4. In Planta Assessment of the Biocontrol Potential of Fungal Isolates Against Meloidogyne incognita

3. Discussion

3.1. Fungal Diversity Associated with Cyst Nematodes and Soil Samples

3.2. In Vitro Evaluation of Fungal Isolates Against Meloidogyne incognita

3.3. In Planta Assessment of the Biocontrol Potential of Fungal Isolates Against Meloidogyne incognita

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Processing

4.2. Fungal Isolation and Culture Preparation

4.3. Nematode Meloidogyne incognita and Molecular Confirmation

4.4. In Vitro Evaluation of the Biological Control Potential of Selected Fungal Isolates Against Meloidogyne incognita

4.5. In Planta Bioassay Evaluation of the Biological Control Potential

4.6. Molecular Identification of Fungal Isolates

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitehead, A.G. Sedentary endoparasites of roots and tubers (I. Globodera and Heterodera). In Plant Nematode Control; Whitehead, A.G., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1998; pp. 146–208. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, K.; Rowe, J.A. Distribution and economic importance. In The Cyst Nematodes; Sharma, S.B., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hodda, M.; Cook, D.C. Economic impact from unrestricted spread of potato cyst nematodes in Australia. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, A.Y.; Weerasooriya, D.K.; Bradley, C.A.; Allen, T.W.; Esker, P.D. Dissecting the economic impact of soybean diseases in the United States over two decades. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylka, G. New Data-Based Calculator Estimates Economic Yield Loss from SCN in Individual Fields. Iowa State University. Extension and Outreach. Integrated Crop Management. 2023. Available online: https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2023/11/new-data-based-calculator-estimates-economic-yield-loss-scn-individual-fields (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Turner, S.J.; Subbotin, S.A. Cyst nematodes. In Plant Nematology; Perry, R.N., Moens, M., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2013; pp. 109–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngala, B.; Mariette, N.; Ianszen, M.; Dewaegeneire, P.; Denis, M.-C.; Porte, C.; Piriou, C.; Robilliard, E.; Couetil, A.; Nguema-Ona, E.; et al. Hatching Induction of Cyst Nematodes in Bare Soils Drenched with Root Exudates Under Controlled Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 602825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, M. Arrested Development in Plant Parasitic. Helminthol. Abstr. B 1989, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, K.; Jones, P. Investigations into the chemoattraction of the potato cyst nematodes Globodera rostochiensis and G. pallida towards fractionated potato root leachate. Nematology 2003, 5, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairwa, A.; Venkatasalam, E.P.; Umamaheswari, R.; Sudha, R.; Singh, B.P. Effect of cultural practices on potato cyst nematode population dynamics and potato tuber yield. Indian J. Hortic. 2017, 74, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.J. Population decline of potato cyst nematodes (Globodera rostochiensis, G. pallida) in field soils in Northern Ireland. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1996, 129, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duceppe, M.O.; Lafond-Lapalme, J.; Palomares-Rius, J.E.; Sabeh, M.; Blok, V.; Moffett, P.; Mimee, B. Analysis of survival and hatching transcriptomes from potato cyst nematodes, Globodera rostochiensis and G. pallida. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, A.M.; Back, M.; Blok, V.C. Population dynamics of the potato cyst nematode, Globodera pallida, in relation to temperature, potato cultivar and nematicide application. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelsey, P.; Kettle, H.; MacKenzie, K.; Blok, V. Potential impacts of climate change on the threat of potato cyst nematode species in Great Britain. Plant Pathol. 2018, 67, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, C.; Heuer, H.; Westphal, A. Impact of cropping sequences and production strategies on soil suppressiveness against cereal cyst nematodes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 107, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, N.; Hu, W.; Haarith, D.; Chen, S.; Bushley, K. Corn and soybean host root endophytic fungi with toxicity toward the soybean cyst nematode. Phytopathology 2020, 110, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerry, B.R.; Crump, D.H.; Mullen, L.A. Parasitic fungi, soil moisture and multiplication of the cereal cyst-nematode, Heterodera avenae. Nematologica 1980, 26, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carris, L.M.; Glawe, D.A.; Smyth, C.A.; Edwards, D.I. Fungi associated with populations of Heterodera glycines in two Illinois soybean fields. Mycologia 1989, 81, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, D.H. Fungal species isolated from beet (BCN), cereal (CCN) and potato (PCN) cyst nematodes. In Methods for Studying Nematophagous Fungi; Kerry, B.R., Crump, D.H., Eds.; International Union of Biological Sciences: Paris, France, 1991; pp. 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dackman, C. Fungal parasites of the potato cyst nematode Globodera rostochiensis: Isolation and reinfection. J. Nematol. 1990, 22, 594–597. [Google Scholar]

- Crump, D.H.; Flynn, C.A. Isolation and screening of fungi for the biological control of potato cyst nematodes. Nematologica 1995, 41, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, A.; Becker, J.O. Components of soil suppressiveness against Heterodera schachtii. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.I.; Hussain, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, M.; Liu, X. Successive soybean-monoculture cropping assembles rhizosphere microbial communities for the soil suppression of soybean cyst nematode. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fiw222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Samac, D.A.; Liu, X.; Chen, S. Microbial communities in the cysts of soybean cyst nematode affected by tillage and biocide in a suppressive soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 119, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarith, D.; Hu, W.; Kim, D.-g.; Showalter, D.N.; Chen, S.; Bushley, K.E. Culturable mycobiome of soya bean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) cysts from a long-term soya bean-corn rotation system is dominated by Fusarium. Fungal Ecol. 2019, 42, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, D. Characterizing A Soybean Cyst Nematode Mycobiome from Waseca Long-term Soy-corn Rotation Experiment in Search of Fungal Biological Control Agents and Bio-nematicides. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Nuaima, R.H.; Ashrafi, S.; Maier, W.; Heuer, H. Fungi isolated from cysts of the beet cyst nematode parasitized its eggs and counterbalanced root damages. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumbam, B.; Amiri, Z.B.; Dandurand, L.M.; Zasada, I.A.; Aime, M.C. Analyses of fungal communities from culture-dependent and-independent studies reveal novel mycobiomes associated with Globodera and Heterodera species. Phytobiomes J. 2024, 8, 621–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swe, A.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Pointing, S.; Jeewon, R.; Hyde, K. Nematode-trapping fungi. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol. 2011, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.Z.; Chen, S.Y. Parasitism of Heterodera glycines by Hirsutella spp. in Minnesota soybean fields. Biol. Control 2000, 19, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Dickson, D.W.; Mitchell, D.J. Pathogenicity of fungi to eggs of Heterodera glycines. J. Nematol. 1996, 28, 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.Z.; Xiang, M.C.; Che, Y.S. The living strategy of nematophagous fungi. Mycoscience 2009, 50, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Dickson, D.W. Biological control of plant-parasitic nematodes. In Practical Plant Nematology; Manzanilla-Lopez, R.H., Marban-Mendoza, N., Eds.; Biblioteca Basica de Agricultura: Montecillo, Texcoco, Mexico, 2012; pp. 761–811. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann, J.; Sikora, R.A. Toxicity of fungal endophyte secondary metabolites to plant parasitic nematodes and soil-borne plant pathogenic fungi. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1996, 102, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, W.K.; Raizada, M.N. The diversity of anti-microbial secondary metabolites produced by fungal endophytes: An interdisciplinary perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 44840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarith, D.; Kim, D.; Strom, N.B.; Chen, S.; Bushley, K.E. In vitro screening of a culturable soybean cyst nematode cyst mycobiome for potential biological control agents and biopesticides. Phytopathology 2000, 110, 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerry, B.R. Rhizosphere interactions and the exploitation of microbial agents for the biological control of plant-parasitic nematodes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2000, 38, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosavi, M.R.; Zare, R. Fungi as biological control agents of plant-parasitic nematodes. In Plant Defense: Biological Control, Progress in Biological Control 12; Merillon, J.M., Ramawat, K.G., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 67–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.L.; Roberts, D.P. Combinations of biocontrol agents for management of plant-parasitic nematodes and soilborne plant-pathogenic fungi. J. Nematol. 2002, 34, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Llorca, L.V.; Olivares-Bernabeu, C.; Salinas, J.; Jansson, H.B.; Kolattukudy, P.E. Prepenetration events in fungal parasitism of nematode eggs. Mycol. Res. 2002, 106, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, G.R. Biological Control of Plant-Parasitic Nematodes: Soil Ecosystem Management in Sustainable Agriculture; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2014; p. 501. [Google Scholar]

- Timper, P. Utilization of biological control for managing plant-parasitic nematodes. In Biological Control of Plant-Parasitic Nematodes: Progress in Biological Control; Davies, K., Spiegel, Y., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 11, pp. 259–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, P.R.P.; Soares, P.L.M.; Santos, J.M.; Silveira, A.J. Nematophagous fungi: Formulation mass production and application technology. In Biocontrol Agents of Phytonematodes; Askary, T.H., Martinelli, P.R.P., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2015; pp. 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Köhl, J.; Postma, J.; Nicot, P.; Ruocco, M.; Blum, B. Stepwise screening of microorganisms for commercial use in biological control of plant-pathogenic fungi and bacteria. Biol. Control. 2011, 57, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainer, M.S.; Pognant-Gros, J.; Quiroz, R.D.L.C.; González, C.N.A.; Mateille, T.; Roussos, S. Commercial biological control agents targeted against plant-parasitic root-knot nematodes. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2014, 57, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, M.K.; Khan, M.R. Nematophagous Fungi: Ecology diversity and greographical distribution. In Biocontrol Agents of Phytonematodes; Askary, T.H., Martinelli, P.R.P., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2015; pp. 126–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fravel, D.R. Commercialization and implementation of biocontrol. Annu. Rev. Phytopatol. 2005, 43, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glare, T.; Caradus, J.; Gelernter, W.; Jackson, T.; Keyhani, N.; Köhl, J.; Marrone, P.; Morin, L.; Stewart, A. Have biopesticides come of age? Trends Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Nizamani, M.M.; Wu, Y.; Wei, S.; Wang, Y.; Xie, X. Diversity of fungi isolated from potato nematode cysts in Guizhou province, China. J. Fungi. 2023, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.J.; de Andrade, E.; Mota, M.; Nobrega, F.; Vicente, C.; Rusinque, L.; Inácio, M.L. Potato Cyst Nematodes: Geographical Distribution, Phylogenetic Relationships and Integrated Pest Management Outcomes in Portugal. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 606178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro, V.; Stanisavljevic, R.; Nikolic, B.; Tabakovic, M.; Secanski, M.; Tosi, S. Diversity of Mycobiota Associated with the Cereal Cyst Nematode Heterodera filipjevi Originating from Some Localities of the Pannonian Plain in Serbia. Biology 2021, 10, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Zhang, K.Q.; Xu, J. Fungi-Nematode Interactions: Diversity, Ecology, and Biocontrol Prospects in Agriculture. J. Fungi. 2020, 6, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, R.A.; Coyne, D.; Hallmann, J.; Timper, P. Plant Parasitic Nematodes in Subtropical and Tropical Agriculture, 3rd ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Dubey, M.; McEwan, K.; Menzel, U.; Franko, M.A.; Viketoft, M.; Jensen, D.F.; Karlsson, M. Evaluation of Clonostachys rosea for control of plant-parasitic nematodes in soil and in roots of carrot and wheat. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.; Broberg, M.; Haarith, D.; Broberg, A.; Bushley, K.E.; Durling, M.B.; Viketoft, M.; Jensen, D.F.; Dubey, M.; Karlsson, M. Natural variation of root lesion nematode antagonism in the biocontrol fungus Clonostachys rosea and identification of biocontrol factors through genome-wide association mapping. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 2264–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.I.; Loffredo, A.; Borneman, J.; Becker, J.O. Biocontrol Efficacy Among Strains of Pochonia chlamydosporia Obtained from a Root-Knot Nematode Suppressive Soil. J. Nematol. 2012, 44, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Yesayan, A.; Yesayan, T.; Babayan, B.; Esoyan, S.; Hayrapetyan, A.; Sevoyan, G.; Melkumyan, M. Carnivorous fungi application for pesticide-free vegetable cultivation. Funct. Food Sci. 2024, 4, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Pérez, C.J.; Collantes-González, R.D.; Pitti-Caballero, J.; Peraza-Padilla, W.; Hofmann, T.A. Nematophagous fungi for integrated management of Meloidogyne (Tylenchida): A review of taxonomic diversity, mechanisms of action and potential as biological control agents. Sci. Agropecu. 2025, 16, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas Soares, F.E.; Chaves, F.C.; Martins, M.F. Diversity and ecological distribution of nematophagous fungi. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 129, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, K.Q. Biological Control of Plant-Parasitic Nematodes by Nematophagous Fungi. In Nematode-Trapping Fungi. Fungal Diversity Research Series; Zhang, K.Q., Hyde, K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarith, D.; Ali, S.S.; Abebe, E. Fungal communities associated with Heterodera glycines cysts and their potential as biological control agents and sources of secondary metabolites. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 578454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitao, J.K.; Meyer, S.L.F.; Oliver, J.E.; Schmidt, W.F.; Chitwood, D.J. Isolation of flavipin, a fungus compound antagonistic to plant-parasitic nematodes. Nematology 2002, 4, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.G.; Tao, N.; Liu, W.J.; Yang, J.K.; Huang, X.W.; Liu, X.Y.; Tu, H.H.; Gan, Z.W.; Zhang, K.Q. Regulation of subtilisin-like protease prC expression by nematode cuticle in the nematophagous fungus Clonostachys rosea. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 3243–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.G.; Tu, H.H.; Liu, X.Y.; Tao, N.; Zhang, K.Q. PacC in the nematophagous fungus Clonostachys rosea controls virulence to nematodes. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 1868–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, R.; Mendoza-de-Gives, P.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L.; López-Arellano, M.E.; Gamboa-Angulo, M.; Hanako Rosas-Saito, G.; Reyes-Estébanez, M.; Guadalupe García-Rubio, V. In vitro lethal activity of the nematophagous fungus Clonostachys rosea (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) against nematodes of five different taxa. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3501827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Dubey, M.; Broberg, A.; Viketoft, M.; Jensen, D.F.; Karlsson, M. Deletion of the non-ribosomal peptide synthetase gene nps1 in the fungus Clonostachys rosea attenuates antagonism and biocontrol of plant pathogenic Fusarium and nematodes. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 1698–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucky, T.; Sy, E.T.; Egger, J.; Mathlouthi, E.; Krauss, J.; De Gianni, L.; Ruthes, A.C.; Dahlin, P. Control of the plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita in soil and on tomato roots by Clonostachys rosea. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 135, lxae111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Y.; He, H.P.; Shen, Y.M.; Zhang, K.Q. Nematicidal epipolysulfanyldioxopiperazines from Gliocladium roseum. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1510–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, J.D.; Haydock, P.P.J.; Hare, M.C.; Woods, S.R.; Crump, D.H. Effect of the fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia and fosthiazate on the multiplication rate of potato cyst nematodes (Globodera pallida and G. rostochiensis) in potato crops grown under UK field conditions. Biol. Control 2008, 46, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerry, B.R.; Crump, D.H.; Mullen, L.A. Studies of the cereal cyst-nematode, Heterodera avenae under continuous cereals, 1975–1978. II. Fungal parasitism of nematode females and eggs. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1982, 100, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J. The influence of fungal parasites on the population dynamics of Heterodera schachtii on oil radish. Nematologica 1982, 28, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Crump, D.H.; Irving, F. Selection of isolates and methods of culturing Verticillium chlamydosporium and its efficacy as a biological control agent of beet and potato cyst nematodes. Nematologica 1992, 38, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Z.A.; Mahmood, I. Some observations on the management of the wilt disease complex of pigeonpea by treatment with a vesicular arbuscular fungus and biocontrol agents for nematodes. Biores. Technol. 1995, 54, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.C.; Self, L.H.; Tyler, D.D. Fungal parasitism of soybean cyst nematode, Heterodera glycines (Nemata: Heteroderidae), in differing cropping-tillage regimes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 1996, 5, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Jones, G.; White, J.F.; Rodriguez-Kabana, R. Phytonematode pathology: Ultrastructural studies. I. Parasitism of Meloidogyne arenaria eggs by Verticillium chlamydosporium. Nematropica 1983, 13, 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L.; Li, L.F.; Li, D.X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, K.; Niu, X. Yellow pigment aurovertins mediate interactions between the pathogenic fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia and its nematode host. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 6577–6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, R.T.; Monteiro, T.S.A.; Coutinho, R.R.; Silva, J.G.; Freitas, L.G. Pochonia chlamydosporia no controle do nematoide de galhas em bananeira. Nematropica 2019, 49, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y. Development and Function of Constricting Ring-Forming Nematophagous Fungi. Doctoral Dissertation, Miami University, Miami, FL, USA, 2014; p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Eken, C.; Uysal, G.; Demir, D.; Çalışkan, S.; Sevindik, E.; Çağlayan, K. Use of Arthrobotrys spp. in biocontrol of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Eur. J. Biol. Res. 2023, 13, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gené, J.; Verdejo-Lucas, S.; Stchigel, A.M.; Sorribas, F.J.; Guarro, J. Microbial parasites associated with Tylenchulus semipenetrans in citrus orchards of Catalonia, Spain. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2005, 15, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A. Mechanisms involved in nematode control by endophytic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2016, 54, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Z.A.; Akhtar, M.S. Effects of antagonistic fungi, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alone and in combination on the reproduction of Meloidogyne incognita and growth of tomato. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2009, 75, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikandar, A.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Fan, H.; Xuan, Y.; Chen, L.; Duan, Y. In vitro evaluation of Penicillium chrysogenum Snef1216 against Meloidogyne incognita (root-knot nematode). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, I.; Khan, R.A.A.; Masood, T.; Baig, A.; Siddique, I.; Haq, S. Biological control of root knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita, in vitro, greenhouse and field in cucumber. Biol. Control 2021, 152, 104429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Yu, N.H.; Lee, Y.; Hwang, I.M.; Bui, H.X.; Kim, J.-C. Nematicidal activity of cyclopiazonic acid derived from Penicillium commune against root-knot nematodes and optimization of the culture fermentation process. Front. Microbial. 2021, 12, 726504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidayat, I. Dark Septate Endophytes and Their Role in Enhancing Plant Resistance to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. In Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Stress Management. Microorganisms for Sustainability; Sayyed, R., Arora, N., Reddy, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 12, pp. 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Cesanelli, I.; Diánez, F.; Sánchez-Montesinos, B.; Moreno-Gavíra, A. Advances in the role of dark septate endophytes in the plant resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbring-Hertz, B.; Jansson, H.B.; Tunlid, A. Nematophagous fungi. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; Nature Publishing Group, Macmillan Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Zhao, F.; Liu, H.; Ma, C.; Jia, X.; Jiang, L.; Fan, Z.; Wang, R. Dynamic proteomic changes and ultrastructural insights into Pochonia chlamydosporia’s parasitism of Parascaris equorum eggs. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1600620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanilla-López, R.H.; Esteves, I.; Finetti-Sialer, M.M.; Hirsch, P.R.; Ward, E.; Devonshire, J.; Hidalgo-Díaz, L. Pochonia chlamydosporia: Advances and challenges to improve its performance as a biological control agent of sedentary endo-parasitic nematodes. J. Nematol. 2013, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.B.; Sun, M.H.; Li, S.D. Identification of mycoparasitism-related genes in Clonostachys rosea 67-1 active against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga-Suazo, P.; Sanfuentes, E.; Le-Feuvre, R. Induced systemic resistance triggered by Clonostachys rosea against Fusarium circinatum in Pinus radiata. For. Res. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, N.; Lopez-Llorca, L.V. Effects on plant growth and root-knot nematode infection of an endophytic GFP transformant of the nematophagous fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia. Symbiosis 2012, 57, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavero-Camacho, I.; Ruiz-Cuenca, A.N.; Cantalapiedra-Navarrete, C.; Castillo, P.; Palomares-Rius, J.E. Diversity of microbial, biocontrol agents and nematode abundance on a susceptible Prunus rootstock under a Meloidogyne root gradient infection. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1386535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalović, O.; Vestergård, M. Can microorganisms assist the survival and parasitism of plant-parasitic nematodes? Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.A.H. Endophytic Fungi and Their Impact on Agroecosystems. In Medicinal Plants: Biodiversity, Sustainable Utilization and Conservation; Khasim, S.M., Long, C., Thammasiri, K., Lutken, H., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, J.; Viaene, N. Nematode extraction: PM 7/119 (1). EPPO Bull. 2013, 43, 471–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO). PM 9/26 (1). EPPO Bull. 2018, 48, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksman, S.A. A method for counting the number of fungi in the soil. J. Bacteriol. 1922, 7, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, J.; Kiewnick, S. Virulence of Meloidogyne incognita populations and Meloidogyne enterolobii on resistant cucurbitaceous and solanaceous plant genotypes. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2018, 125, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiewnick, S.; Wolf, S.; Willareth, M.; Frey, J.E. Identification of the tropical root-knot nematode species Meloidogyne incognita, M. javanica and M. arenaria using a multiplex PCR assay. Nematology 2013, 15, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeck, W.M. Rating scheme for field evaluation of root-knot nematode infestations. Pflanzenschutz Nachr. 1971, 24, 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, E.S. Sample preparation from blood, cells, and other fluids. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes–application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lees, S.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Bairwa, A.; Dipta, B.; Mhatre, P.H.; Venkatasalam, E.P.; Sharma, S.; Tiwari, R.; Singh, B.; Thakur, D.; Naga, K.C.; Maharana, C.; et al. Chaetomium globosum KPC3: An antagonistic fungus against the potato cyst nematode, Globodera rostochiensis. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.L.F.; Robin, N.H.; Liu, X.Z.; Humber, R.A.; Juba, J.; Nitao, J.K. Activity of fungal culture filtrates against soybean cyst nematode and root-knot nematode egg hatch and juvenile motility. Nematology 2004, 6, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahrizsangi, H.S.; Ahmadi, A.R.; Sardooei, Z.A.; Mehdi, S.; Booshehri, S.; Fekrat, F. Detection of fungi associated with cereal cyst nematode, Heterodera filipjevi, on some wheat fields of Khuzestan and effect of isolated Fusarium species on the nematode under in vitro condition. Biol. Control Pests Dis. 2019, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.L.; Huettel, R.N.; Sayre, R.M. Isolation of Fungi from Heterodera glycines and in vitro bioassays for their antagonism to eggs. J. Nematol. 1990, 22, 532–537. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, K.; Afzalinia, S. Introduction of eight fungi isolated from potato golden cyst nematode in Iran. Univ. Yasouj Plant Pathol. Sci. 2022, 11, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, G.; Rodriguez-Kabana, R.; Morgan-Jones, G. Parasitism of eggs of Heterodera glycines and Meloidogyne arenaria by fungi isolated from cysts of H. glycines. Nematropica 1982, 12, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Jones, G.; Rodriguez-Kabana, R. Fungi associated with cysts of potato cyst nematodes in Peru. Nematropica 1986, 16, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Strom, N.; Haarith, D.; Chen, S.; Bushley, K.E. Mycobiome of cysts of the soybean cyst nematode under long term crop rotation. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, S. Mycofloras in cysts, females, and eggs of the soybean cyst nematode in Minnesota. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2002, 19, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Dickson, D.W.; Kimbrough, J.W.; Mcsorley, R.; Mitchell, D.J. Fungi Associated with Females and Cysts of Heterodera glycines in a Florida Soybean Field. J. Nematol. 1994, 26, 296–303. [Google Scholar]

- Clovis, C.J.; Nolan, R.A. Fungi associated with cysts, eggs, and juveniles of the golden nematode (Globodera rostochiensis) in Newfoundland. Nemtologica 1993, 29, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, M. Fungi associated with cysts of Globodera rostochiensis, Heterodera cruciferae and Heterodera schachtii (Nematoda: Heteroderidae). Manas J. Agric. Vet. Life Sci. 2014, 4, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nigh, E.; Thomason, I.; van Gundy, S. Identification and distribution of fungal parasites of Heterodera schachtii eggs in California. Phytopathology 1980, 70, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, A.E.; Al-Bahry, S.N.; Ba-Omar, T.; Verlag, F.B.; Sohne, H. Nematophagous fungi isolated from soil in Oman. Sydowia 2003, 55, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Smaha, D.; Mokrini, F.; Daoudi-Assous, R.; Adimi, A.; Mokabli, A.; Dababat, A. Les antagonistes naturels d’Heterodera avenae dans diverses conditions de cultures de céréales en Algérie. Rev. Mar. Sci. Agron. Vet. 2020, 8, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gintis, B.O.; Morgan-Jones, G.; Rodriguez-Kabana, R. Fungi associated with several developmental stages of Heterodera glycines from an Alabama soybean field soil. Nematropica 1983, 13, 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles, C.M.; Glawe, D.A. Colonization of soybean roots by fungi isolated from cysts of Heterodera glycines. Mycologia 1989, 81, 797–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruthes, A.C.; Dahlin, P. Diversity and Biocontrol Potential of Fungi Associated with Cyst Nematodes and Soils in Swiss Potato Agroecosystems. Plants 2025, 14, 3775. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243775

Ruthes AC, Dahlin P. Diversity and Biocontrol Potential of Fungi Associated with Cyst Nematodes and Soils in Swiss Potato Agroecosystems. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3775. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243775

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuthes, Andrea Caroline, and Paul Dahlin. 2025. "Diversity and Biocontrol Potential of Fungi Associated with Cyst Nematodes and Soils in Swiss Potato Agroecosystems" Plants 14, no. 24: 3775. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243775

APA StyleRuthes, A. C., & Dahlin, P. (2025). Diversity and Biocontrol Potential of Fungi Associated with Cyst Nematodes and Soils in Swiss Potato Agroecosystems. Plants, 14(24), 3775. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243775