Thrips Spatio-Temporal Distribution in Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) Flowers Based on the Flower Structures and Floral Development Stage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

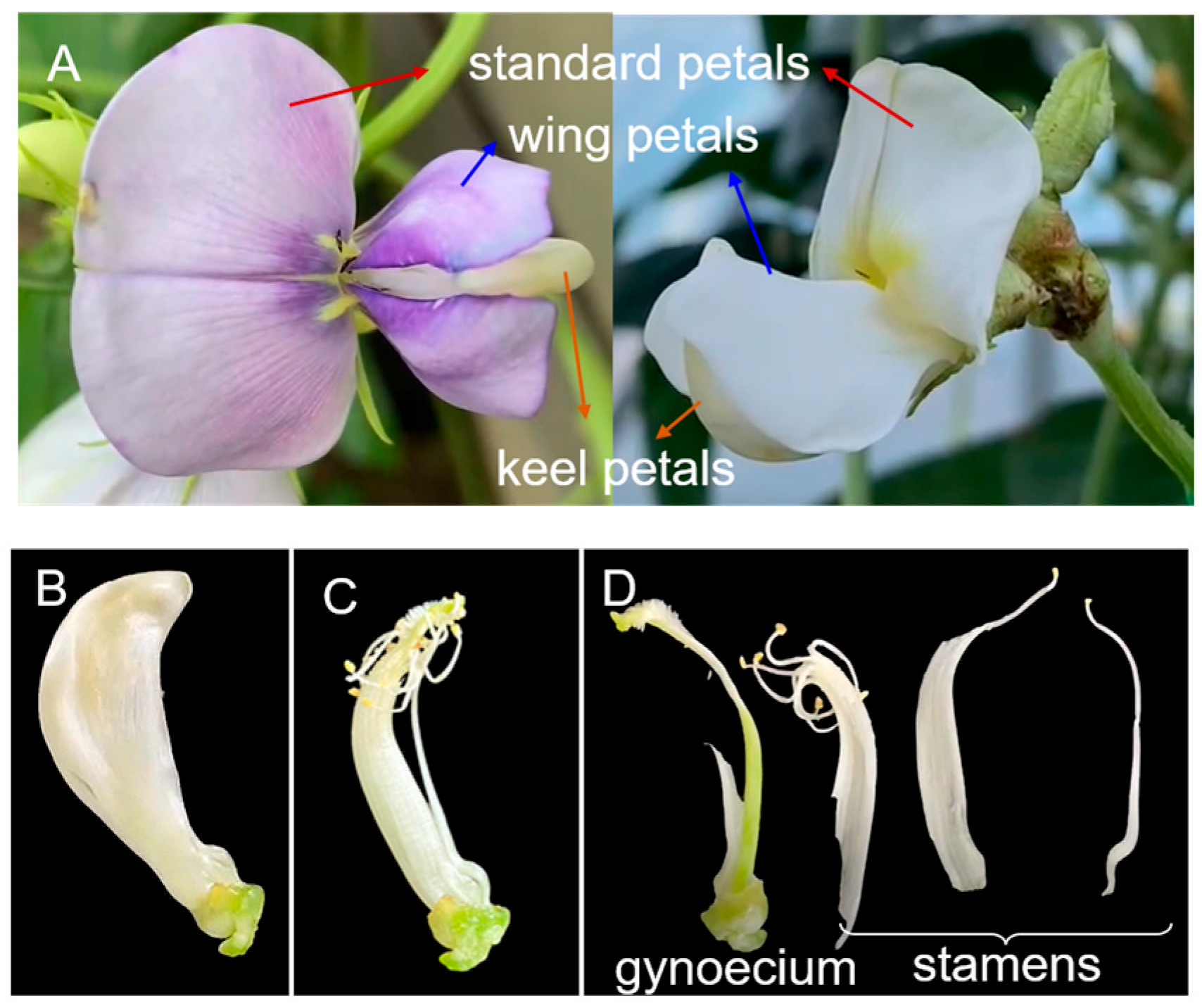

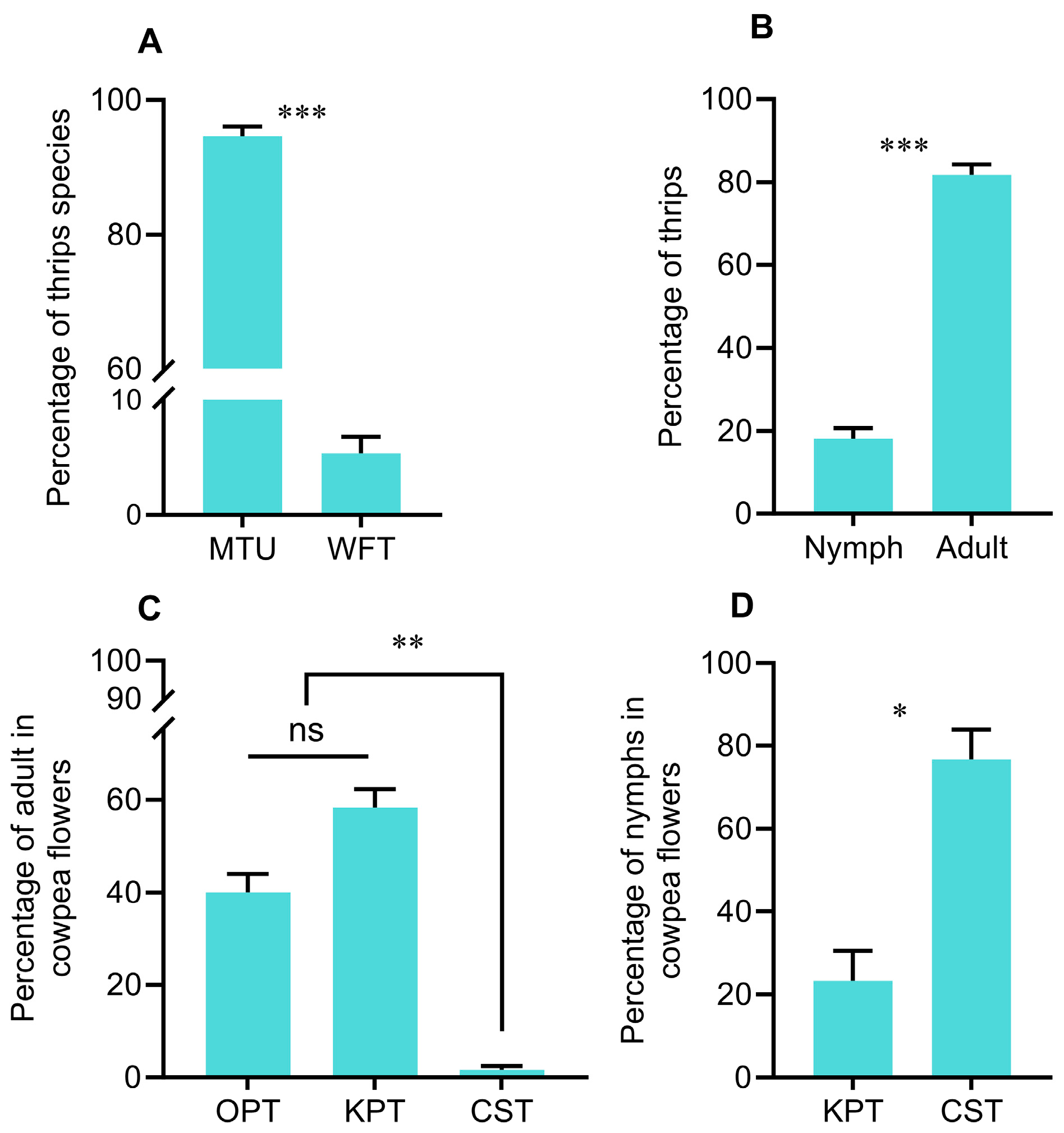

2.1. Thrips Distribution Within a Cowpea Flower

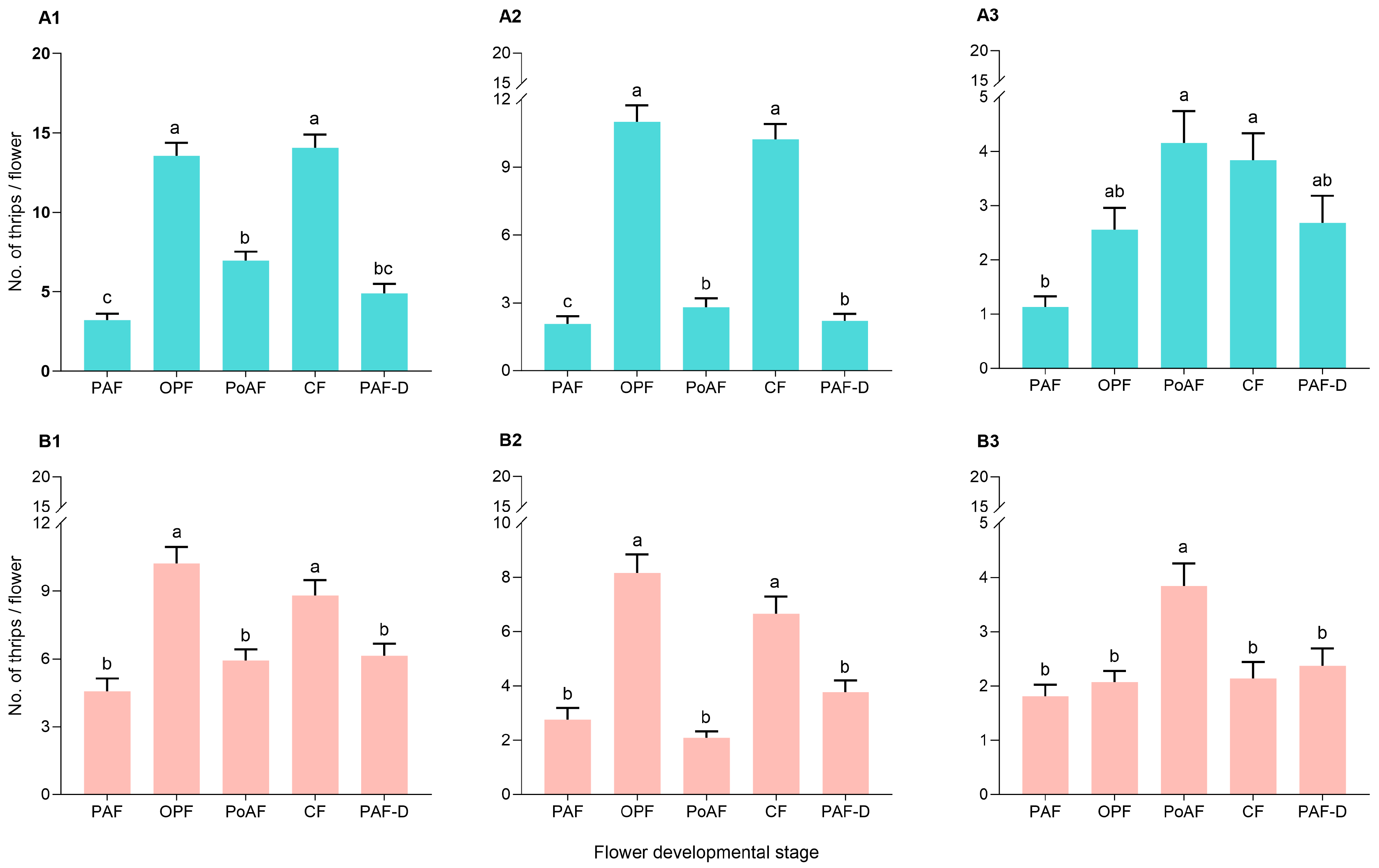

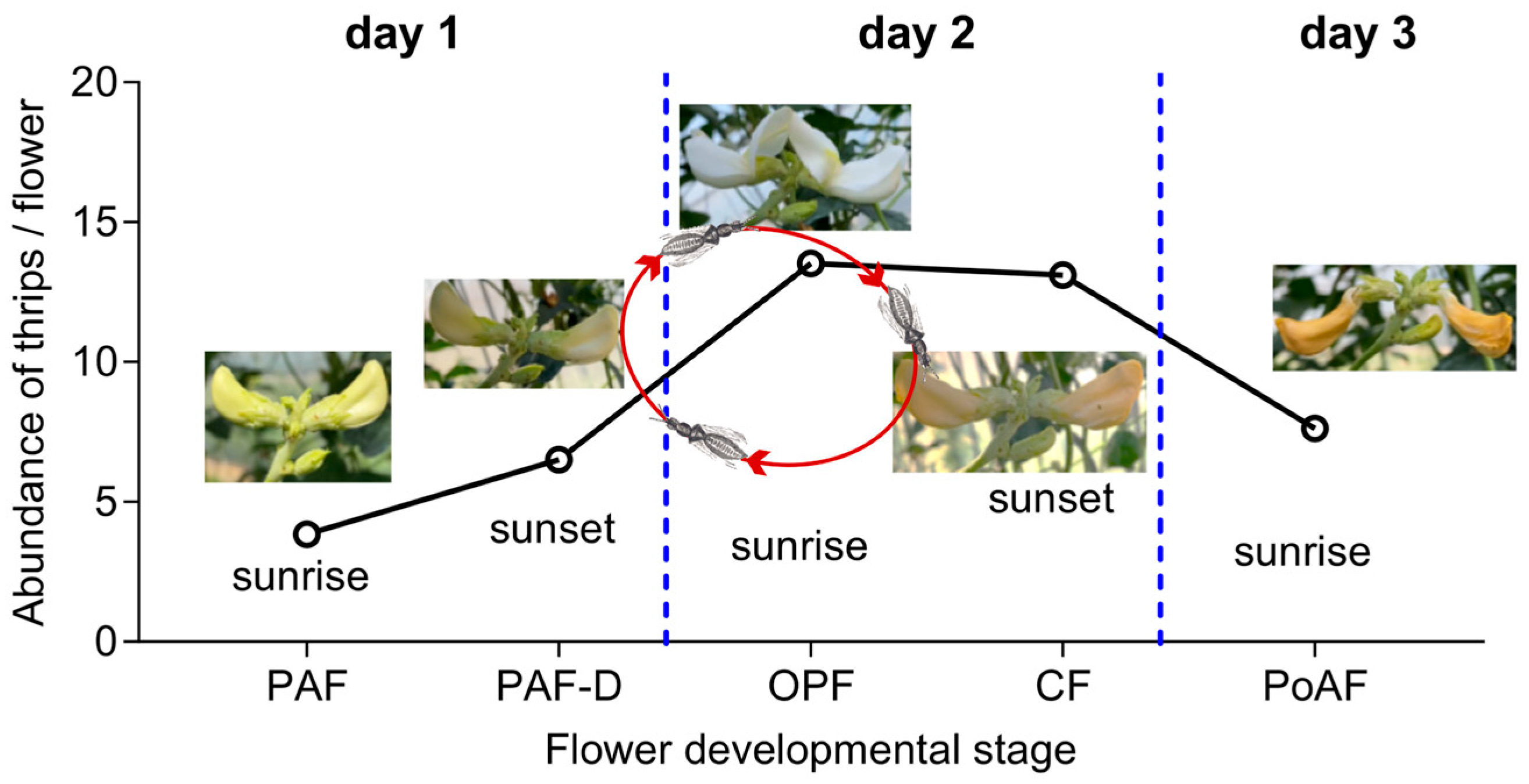

2.2. Abundance of Thrips in Different Flower Ages

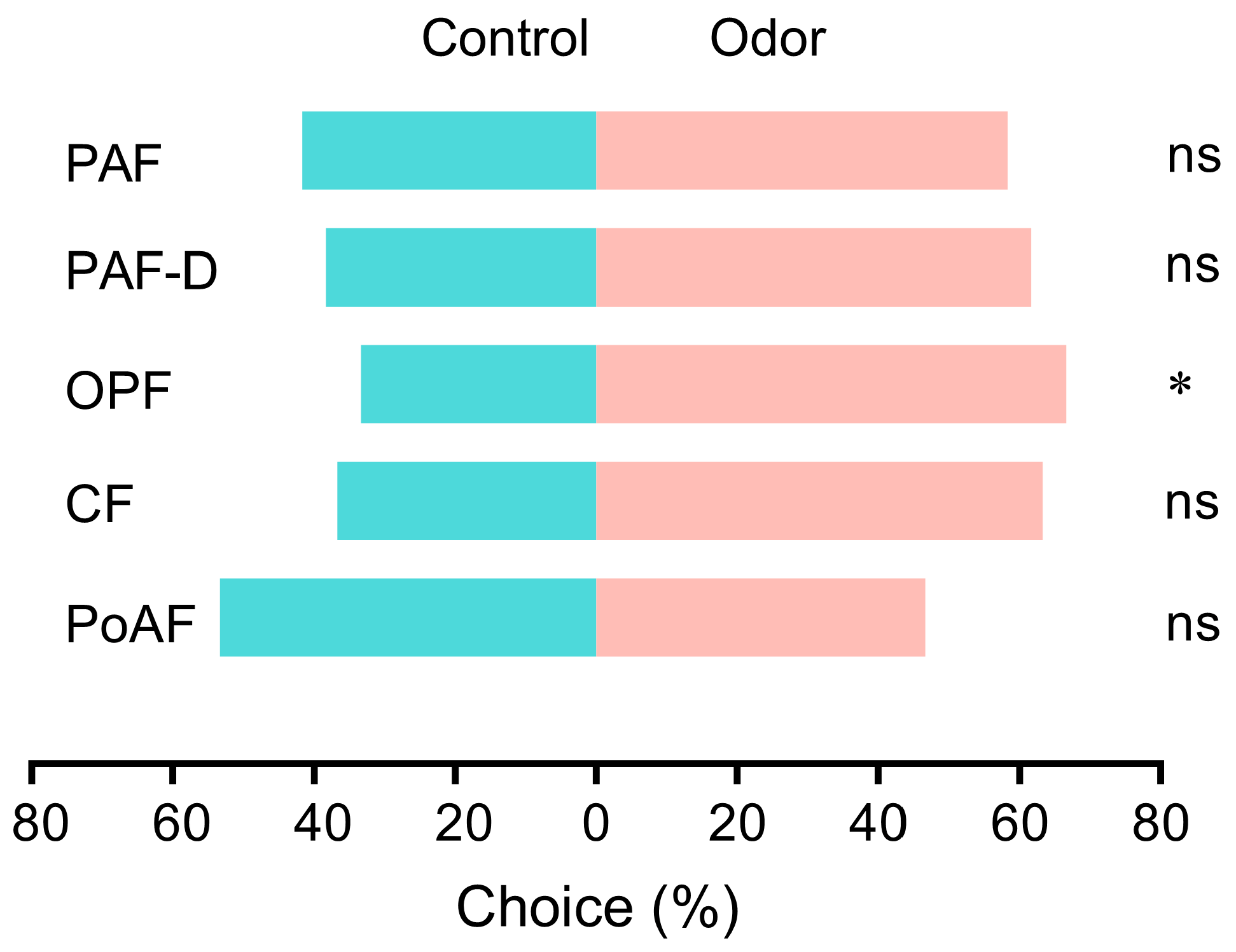

2.3. Behavior of MTU to Flowers

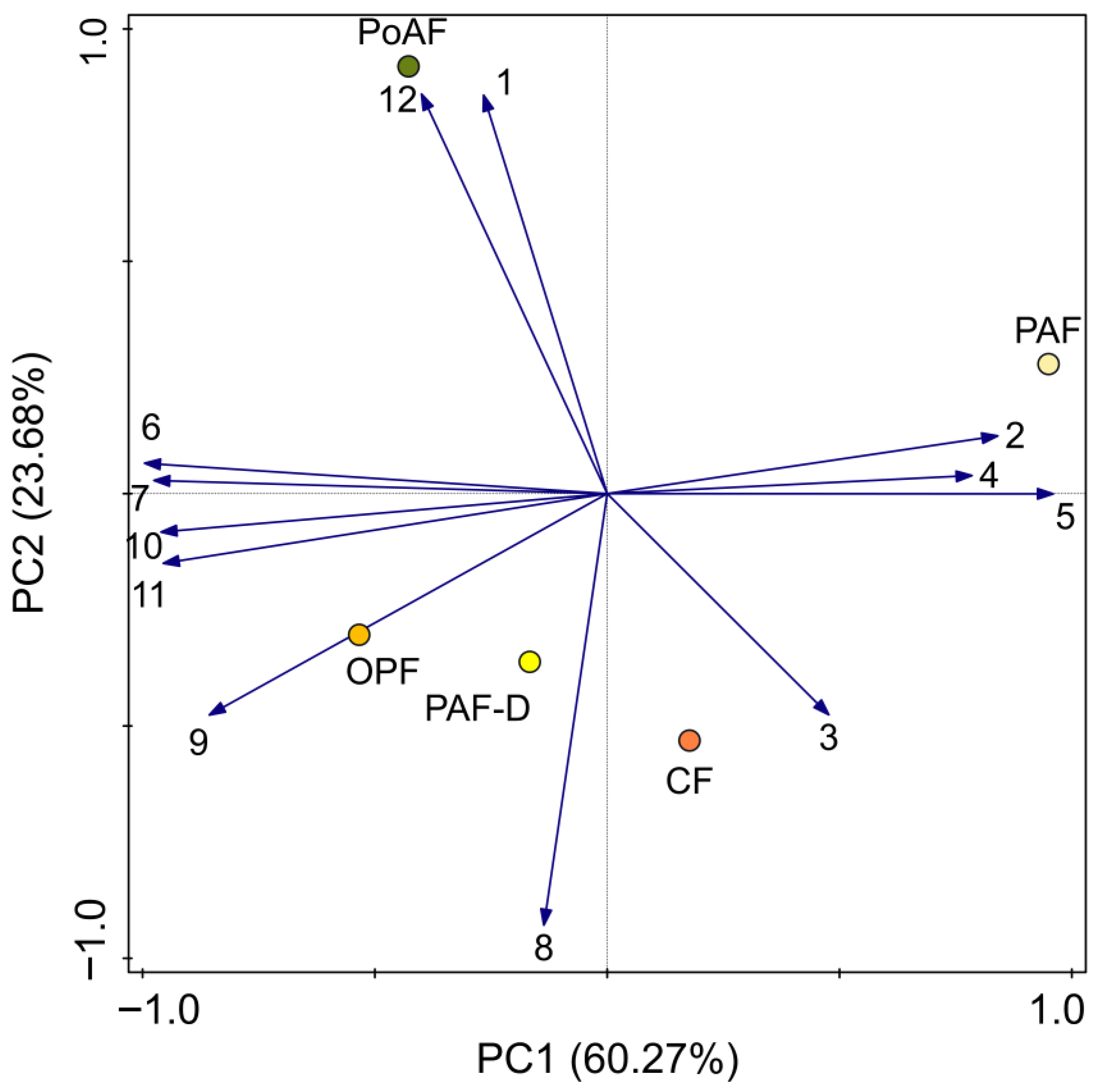

2.4. Differential Chemical Compounds in Flowers

2.5. Speculation on Adult Thrips Dynamics in Cowpea Flowers

3. Discussion

3.1. Spatial Distribution Within a Cowpea Flower

3.2. Volatile-Mediated Regulation of Thrips Abundance in Opening Flowers

3.3. Potential Role of Color in Mediating Thrips Aggregation in Open Flowers

3.4. Potential Movement Patterns of Adult Thrips in Cowpea Flowers

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Field and Plants

4.2. Thrips Species and Distribution Within the Opening Flowers

4.3. Abundance of Thrips Within Floral Development Stage

4.4. Thrips Behavior Assays to Flower Volatiles

4.5. Collection of Flower Volatiles

4.6. Analysis of Extracts

4.7. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morse, J.G.; Hoddle, M.S. Invasion biology of thrips. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitz, S.R.; Gao, Y.; Lei, Z. Thrips: Pests of concern to China and the United States. Agric. Sci. China 2011, 10, 867–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, S.R.; Gao, Y.L.; Kirk, W.D.J.; Hoddle, M.S.; Leiss, K.A.; Funderburk, J.E. Invasion biology, ecology, and management of the western flower thrips. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.D.; Guo, L.H.; Wu, J.H.; Zang, L.S. Thrips in genus Megalurothrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae): Biodiversity, bioecology, and IPM. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2023, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasada Rao, R.D.V.J.; Reddy, A.S.; Reddy, S.V.; Thirumala-Devi, K.; Chander Rao, S.; Manoj Kumar, V.; Subramaniam, K.; T Yellamanda Reddy, T.; Nigam, S.N.; Reddy, D.V.R. The host range of Tobacco streak virus in India and transmission by thrips. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2003, 142, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Guo, J.; Reitz, S.R.; Lei, Z.; Wu, S. A global invasion by the thrip, Frankliniella occidentalis: Current virus vector status and its management. Insect Sci. 2020, 27, 626–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Tang, L.; Zhang, X.; Xing, Z.; Lei, Z.; Gao, Y. A decade of a thrips invasion in China: Lessons learned. Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Reitz, S.R. Western flower thrips resistance to insecticides: Detection, mechanisms and management strategies. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloyd, R.A. Western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis) management on ornamental crops grown in greenhouses: Have we reached an impasse? Pest Technol. 2009, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mainali, B.P.; Lim, U.T. Behavioral response of western flower thrips to visual and olfactory cues. J. Insect Behav. 2011, 24, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.A.; Senior, L.J.; Brown, P.H.; Duff, J. Relative abundance and temporal distribution of adult Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) and Frankliniella schultzei (Trybom) on French bean, lettuce, tomato and zucchini crops in relation to crop age. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showkat, A.; Ahmad, S.B.; Khan, I.A.; Mir, S.A.; Banoo, P.; Khan, Z.S.; Khan, I.A. Population densities of blossom thrips at different phenological stages of apple in Kashmir. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 1268–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.; Hereward, J.P.; Walter, G.H.; Wilson, L.J.; Furlong, M.J. Seasonal abundance of cotton thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) across crop and non-crop vegetation in an Australian cotton producing region. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 256, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wu, S.; Xing, Z.; Gao, Y.; Cai, W.; Lei, Z. Abundances of thrips on plants in vegetative and flowering stages are related to plant volatiles. J. Appl. Entomol. 2020, 144, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiers, E.; de Kogel, W.J.; Balkema-Boomstra, A.; Mollema, C. Flower visitation and oviposition behaviour of Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysan., Thripidae) on cucumber plants. J. Appl. Entomol. 2000, 124, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R.; Seal, D.R.; Schaffer, B.; Liburd, O.E.; Khan, R.A. Within-plant and within-field distribution patterns of Asian bean thrips and melon thrips in snap bean. Insects 2023, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wäckers, F.L.; Romeis, J.; van Rijn, P. Nectar and pollen feeding by insect herbivores and implications for multitrophic interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007, 52, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suso, M.J.; Harder, L.; Moreno, M.T.; Maalouf, F. New strategies for increasing heterozygosity in crops: Vicia faba mating system as a study case. Euphytica 2005, 143, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, B.P.; Lim, U.T. Use of flower model trap to reduce the infestation of greenhouse whitefly on tomato. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2008, 11, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, B.P.; Lim, U.T. Evaluation of chrysanthemum flower model trap to attract two Frankliniella thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2008, 11, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, U.T.; Kim, E.; Mainali, B.P. Flower model traps reduced thrips infestations on a pepper crop in field. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2013, 16, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkesorn, J.; Milne, J.R.; Kitthawee, S. Pattern and shape effects of orchid flower traps on attractiveness of Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in an orchid farm. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2017, 51, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhi, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, R.; Wang, C.; Shang, B.; Gao, Y. Behavioral responses of Frankliniella occidentalis to floral volatiles combined with different background visual cues. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2018, 12, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wu, S.; Xing, Z.; Xu, R.; Cai, W.; Lei, Z. Behavioral responses of western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis) to visual and olfactory cues at short distances. Insects 2020, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, A.E.; Wood, M.J.; Frend, H.O.; Butt, T.M.; Allen, W.L. Visual modelling can optimise the appearance and capture efficiency of sticky traps used to manage insect pests. J. Pest Sci. 2023, 97, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridi, E.; Suso, M.J.; Ortiz-Sánchez, F.J.; Bebeli, P.J. Investigation of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.)–insect pollinator interactions aiming to increase cowpea yield and define new breeding tools. Ecologies 2023, 4, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Qiu, H.; Zhao, J.; Han, D.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, A.; Chen, J.; Li, L. Volatiles from non-host plant Baccaurea ramiflora (Malpighiales: Phyllanthaceae) attract cowpea thrips, Megalurothrips usitatus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2025, toaf223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.C.; Foster, B.J.; Rafter, M.A.; Walter, G.H. Tiny insects against the weather-flight and foraging patterns of Frankliniella schultzei (Thripidae) not altered by onset of rainfall. Insect Sci. 2018, 25, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, S.R. Biology and ecology of the western flower thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae): The making of a pest. Fla. Entomol. 2009, 92, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.G. Plant Systematics, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 275–448. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe, B.K.; Alemayehu, M.T. A review of the nutritional use of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp) for human and animal diets. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Chang, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H. Attraction effect of different colored cards on thrips Frankliniella intonsa in cowpea greenhouses in China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, Y.; Kawakita, A. Leaf shape deters plant processing by an herbivorous weevil. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, W.D.J. Aggregation and mating of thrips in flowers of Calystegia sepium. Ecol. Entomol. 1985, 10, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellaneda, J.; Díaz, M.; Coy-Barrera, E.; Rodríguez, D.; Osorio, C. Rose volatile compounds allow the design of new control strategies for the western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis). J. Pest Sci. 2019, 94, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andargie, M.; Knudsen, J.T.; Pasquet, R.S.; Gowda, B.S.; Muluvi, G.M.; Timko, M.P. Mapping of quantitative trait loci for floral scent compounds in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.). Plant Breed. 2014, 133, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, W.D.J.; de Kogel, W.J.; Koschier, E.H.; Teulon, D.A.J. Semiochemicals for thrips and their use in pest management. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021, 66, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teulon, D.A.J.; Davidson, M.M.; Hedderley, D.I.; James, D.E.; Fletcher, C.D.; Larsen, L.; Green, V.C.; Perry, N.B. 4-Pyridyl carbonyl and related compounds as thrips lures: Effectiveness for onion thrips and New Zealand flower thrips in field experiments. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 6198–6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, T.; Imai, T.; Maekawa, M. Methyl anthranilate as an attractant for two thrips species and the thrips parasitoid Ceranisus menes. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000, 26, 2557–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Owusu, J.; Vuts, J.; Caulfield, J.C.; Woodcock, C.M.; Withall, D.M.; Hooper, A.M.; Osafo-Acquaah, S.; Birkett, M.A. Identification of semiochemicals from cowpea, Vigna unguiculata, for low-input management of the legume pod borer, Maruca vitrata. J. Chem. Ecol. 2020, 46, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, A.C.; García-Sarrió, M.J.; Sanz, M.L. Volatile sampling by headspace techniques. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 71, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, O.E.; Olotuah, O.F.; Akerele, V. Floral biology and pollination ecology of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp). Mod. Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingha, B.N.; Jackai, L.E.; Amoah, B.A.; Akotsen-Mensah, C. Pollinators on cowpea Vigna unguiculata: Implications for intercropping to enhance biodiversity. Insects 2021, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Reyes, K.; Armstrong, K.F.; van Tol, R.W.H.M.; Teulon, D.A.J.; Bok, M.J. Colour vision in thrips (Thysanoptera). Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2022, 377, 20210282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainali, B.P.; Lim, U.T. Circular yellow sticky trap with black background enhances attraction of Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2010, 45, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D.A.; Whitney, H.M.; Rands, S.A. Nectar discovery speeds and multimodal displays: Assessing nectar search times in bees with radiating and non-radiating guides. Evol. Ecol. 2017, 31, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiepiel, I.; Johnson, S.D. Responses of butterflies to visual and olfactory signals of flowers of the bush lily Clivia miniata. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2021, 15, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschier, E.H.; de Kogel, W.J.; Visser, J.H. Assessing the attractiveness of volatile plant compounds to western flower thrips Frankliniella occidentalis. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000, 26, 2643–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q. Systematics of Thripidae from China (Thysanoptera: Terebrantia). Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Study of Thripidae from China (Thysanoptera: Terebrantia). Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gregg, P.C.; Del Socorro, A.P.; Landolt, P.J. Advances in attract-and-kill for agricultural pests: Beyond pheromones. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.; Aranda-Valera, E.; Quesada-Moraga, E. Lure-and-infect and lure-and-kill devices based on Metarhizium brunneum for spotted wing Drosophila control. J. Pest Sci. 2018, 91, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Component | PAF | PAF-D | OPF | CF | PoAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ethyl (E)-4-decenoate | 0.369 ± 0.045 a | 0.371 ± 0.222 a | 0.630 ± 0.250 a | 0.380 ± 0.228 a | 0.454 ± 0.180 a |

| 2 | (E)-3-decenoic acid | 0.148 ± 0.037 a | 0.032 ± 0.019 b | - | - | - |

| 3 | 3-methyl-undecane | - | 0.077 ± 0.0157 b | 0.106 ± 0.042 a | 0.209 ± 0.126 a | - |

| 4 | hexadecane | 0.286 ± 0.037 a | 0.260 ± 0.037 a | 0.165 ± 0.067 a | 0.442 ± 0.150 a | 0.176 ± 0.034 a |

| 5 | octadecane | 0.365 ± 0.044 a | 0.297 ± 0.037 a | 0.233 ± 0.095 a | 0.399 ± 0.070 a | 0.173 ± 0.029 a |

| 6 | neophytadiene | 0.110 ± 0.003 c | 0.248 ± 0.061 b | 0.359 ± 0.03 a | 0.249 ± 0.159 b | 0.191 ± 0.029 bc |

| 7 | 3-methyl-dodecane | 0.076 ± 0.045 a | 0.193 ± 0.064 a | 0.249 ± 0.098 a | 0.187 ± 0.112 a | 0.158 ± 0.066 a |

| 8 | n-hexadecanoic acid | 0.046 ± 0.027 a | 0.195 ± 0.117 a | 0.165 ± 0.022 a | 0.193 ± 0.059 a | 0.026 ± 0.026 a |

| 9 | ethyl (Z)-4-decenoate | - | 0.082 ± 0.049 a | 0.226 ± 0.090 a | 0.119 ± 0.071 a | 0.043 ± 0.017 a |

| 10 | (E)-2-dodecenol | - | 0.041 ± 0.005 a | 0.075 ± 0.032 a | 0.013 ± 0.008 a | 0.026 ± 0.026 a |

| 11 | 2-nonen-1-ol | - | 0.126 ± 0.025 a | 0.158 ± 0.061 a | 0.087 ± 0.017 a | 0.093 ± 0.023 a |

| 12 | hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | - | - | - | - | 0.047 ± 0.028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, X.; He, Y.; Wei, X.; Zheng, L.; Yu, H.; Huang, X.; Wu, S. Thrips Spatio-Temporal Distribution in Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) Flowers Based on the Flower Structures and Floral Development Stage. Plants 2025, 14, 3753. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243753

Ren X, He Y, Wei X, Zheng L, Yu H, Huang X, Wu S. Thrips Spatio-Temporal Distribution in Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) Flowers Based on the Flower Structures and Floral Development Stage. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3753. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243753

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Xiaoyun, Yuyin He, Xinbao Wei, Li Zheng, Haitao Yu, Xunbing Huang, and Shengyong Wu. 2025. "Thrips Spatio-Temporal Distribution in Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) Flowers Based on the Flower Structures and Floral Development Stage" Plants 14, no. 24: 3753. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243753

APA StyleRen, X., He, Y., Wei, X., Zheng, L., Yu, H., Huang, X., & Wu, S. (2025). Thrips Spatio-Temporal Distribution in Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) Flowers Based on the Flower Structures and Floral Development Stage. Plants, 14(24), 3753. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243753