1. Introduction

Miscanthus, a C4 rhizomatous perennial grass, is recognized as a promising biomass crop [

1] due to its high yield, quality, and tolerance to diverse environmental conditions [

2]. As the biomass product development advances,

Miscanthus is increasingly being used for high-value products, such as nanocellulose, rather than solely for energy generation [

3]. As China focuses on carbon neutrality, the enhancement of carbon sequestration has become vital. Planting

Miscanthus on marginal lands, such as high-salinity soils, contributes to carbon sequestration, helping mitigate climate change by reducing the atmospheric carbon levels [

4,

5,

6]. Therefore, cultivating

Miscanthus as an industrial crop on marginal lands not only provides a sustainable biomass source but also improves the soil quality and the carbon sequestration capacity of these lands [

7,

8].

The propagation of

Miscanthus from seeds is now a reality. Compared with rhizome or in vitro propagation methods, the seed-based propagation is cost-effective, has low carbon emissions, and presents a high multiplication factor (approximately 1:2000) [

9,

10,

11]. Through various breeding programs, new seed-based

Miscanthus hybrids have been developed as alternatives for clonal production [

12]. These hybrids, particularly interspecies hybrids, have shown the potential to match or even exceed the yields of

M. × giganteus on lower-grade lands [

13]. In the United States, field-scale seed production has been successfully achieved by synchronizing the flowering times of

Miscanthus sinensis and

Miscanthus sacchariflorus, significantly increasing the annual yield of viable seeds [

14]. However, initial germination tests observed that

Miscanthus seeds exhibit no dormancy and can germinate immediately after harvest. This characteristic results in spontaneous germination under favorable storage conditions, leading to a loss of seed stocks. Furthermore, germination during storage increases ambient humidity, promoting microbial growth and thereby raising the risk of seed mold and disease incidence. Patanè et al. reported that after one year of storage at room temperature, the germination percentage of

Miscanthus seeds significantly decreases from 95.6% to approximately 60% [

15]. This decline in germination percentage necessitates the use of more seeds for sowing, ultimately increasing cultivation costs.

The importance of seed storage has been recognized since plant domestication. The deterioration of seeds over time, characterized by declines in morphological structure, physiological function, and biochemical integrity [

16], leads to reduced viability and germination failure [

17,

18]. Inappropriate storage conditions can accelerate this process, with temperature, oxygen, and relative humidity acting as critical factors [

19]. For instance, the germination percentage of

Ruppia sinensis seeds remained at 74.4% after 9 months of storage under dry conditions at 5 °C, compared to a decline to 35.7% when stored at room temperature for the same duration [

20]. Currently, systematic research on storing

Miscanthus seeds remains limited. As

Miscanthus gains prominence, developing an economical, efficient, and scalable seed storage system has become an urgent requirement for supporting its industrial expansion.

This study designed six distinct storage methods for Miscanthus and evaluated their effectiveness by evaluating the germination percentages in the 4th and 5th years of storage, as well as by conducting field experiments in the 5th year. The changes in the cellular level were also observed. This study assessed the viability of Miscanthus seeds after long-term storage under various conditions, with the objective of developing an effective storage method to support future large-scale Miscanthus seed cultivation.

3. Discussion

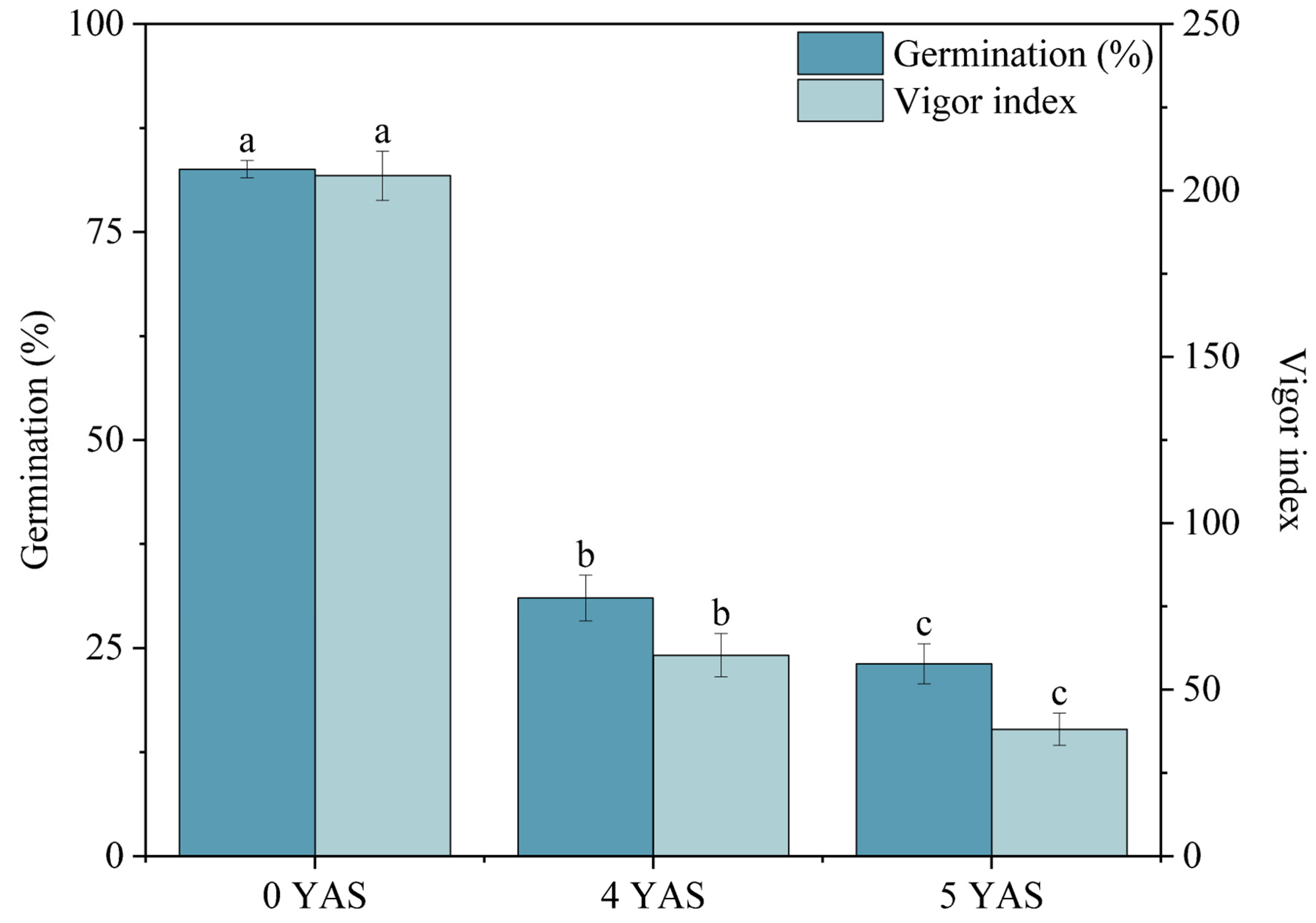

3.1. Miscanthus Seed Dormancy Failure and Short Longevity

Miscanthus seeds do not exhibit dormancy. In 2016, immediately after the

Miscanthus seeds reached maturity, we removed the glumes and promptly initiated germination experiments. The results indicated that the seeds began to germinate rapidly on the second day of the experiment, with a notably high germination percentage. The seed dormancy was defined as the condition under which viable seeds failed to germinate under the optimal temperature, humidity, and oxygen conditions [

21]. This lack of dormancy was disadvantageous for preserving

Miscanthus seeds, as they germinated immediately upon encountering suitable environmental conditions, leading to a reduction in seed numbers. Therefore, it could be essential to dry and store

Miscanthus seeds immediately after harvest to prevent losses due to spontaneous germination.

Miscanthus seeds typically have a short lifespan, attributable not only to their non-dormancy characteristics but also to their inherent genetic traits. The average weight of a thousand Miscanthus seeds was approximately 0.45 g, and their small size limits the available nutrients for consumption. As nutrients were depleted during storage, supporting successful germination has become increasingly challenging. Generally, the M. lutarioriparius seeds and hybrid seeds with M. lutarioriparius as the female parent were the largest in volume, consistent with the observations of this experiment. Specifically, the seeds from M. lutarioriparius (B0129 and Y0101) and the hybrid (Z0101) demonstrated superior germination performance after long-term storage compared to other species, and they also demonstrated stronger vitality in field trials.

3.2. Impact of Storage Conditions on Miscanthus Seed Longevity

In line with the results of this study and those of Meyer et al. [

22],

Miscanthus seeds can be classified as orthodox, indicating that reducing the relative humidity and temperature of the storage environment benefits their longevity [

23]. The use of desiccants effectively preserved the vitality of

Miscanthus seeds at room temperature. In contrast, the other two room temperature storage methods, such as room temperature alone and room temperature with vacuum, failed to support germination in the 4th and 5th years. The successful germination of seeds stored at room temperature with desiccant is likely attributable to the maintenance of low relative humidity, which retards seed aging and degradation. The final moisture content of seeds during storage is influenced by relative humidity, as seeds reach equilibrium with the surrounding water vapor [

24]. Higher relative humidity increases seed moisture content, which accelerates seed aging and reduces germination percentage [

25]. The experimental site, Changsha, has a subtropical monsoon climate with a relative humidity exceeding 50% year-round. The seeds stored at room temperature are continually exposed to high relative humidity, leading to accelerated aging. Using desiccants, a consistently low and stable relative humidity environment was maintained, allowing the

Miscanthus seeds to remain viable even after 5 years of storage at room temperature.

Reducing the temperature was more effective for the long-term preservation of Miscanthus seeds. Under the three different low-temperature storage conditions, Miscanthus seeds maintained higher vitality. Typically, the effect of low temperature desiccants was similar to that of low temperature alone, as desiccants were ineffective at −18 °C. However, during long-term storage, unforeseen power outages may occur, causing the temperature and relative humidity to rise inside the refrigerator. In such cases, the desiccant helps to mitigate the adverse effects of these environmental changes by providing emergency protection. Although the vitality index of the seeds stored under the low temperature conditions was slightly higher than that of seeds stored under the low temperature with desiccant conditions, the difference was not significant and may be due to the inherent seed variability. Overall, the low-temperature storage consistently proved more effective in maintaining the seed vitality than the room-temperature storage.

For

Miscanthus seeds, vacuum storage demonstrated a limited effect on maintaining seed viability. The vacuum treatment, isolating the moisture and oxygen, failed to preserve

Miscanthus seeds during long-term storage, as seeds at room temperature with vacuum lost viability by the fourth year. Moreover, the germination percentage and vitality index of the seeds stored under the low temperature with vacuum conditions were the lowest among the three low-temperature storage methods. This result contrasts sharply with the benefits of vacuum storage reported in other species. For instance, Flores et al. reported that the vacuum treatment prevented a 50% reduction in the germination capacity of

Juglans nigra L. seeds stored at −20 °C for one year [

26]. Similarly, Meena et al. observed that vacuum packaging extended the shelf life of soybean seeds to 18 months without compromising their quality indicators [

27]. Furthermore, Barzali et al. discovered a positive effect on the germination percentage of

Secale graale L. seeds under the room temperature vacuum conditions during a 26-year storage experiment [

28]. Hence, the effectiveness of vacuum storage is highly dependent on species. For seeds such as those of

Miscanthus, the vacuum environment may not adequately suppress aging processes, or the seeds themselves might be more sensitive to the vacuum conditions. Therefore, when formulating storage protocols, it is crucial to fully consider species-specific seed characteristics, rather than treating vacuum storage as a universally applicable optimization method.

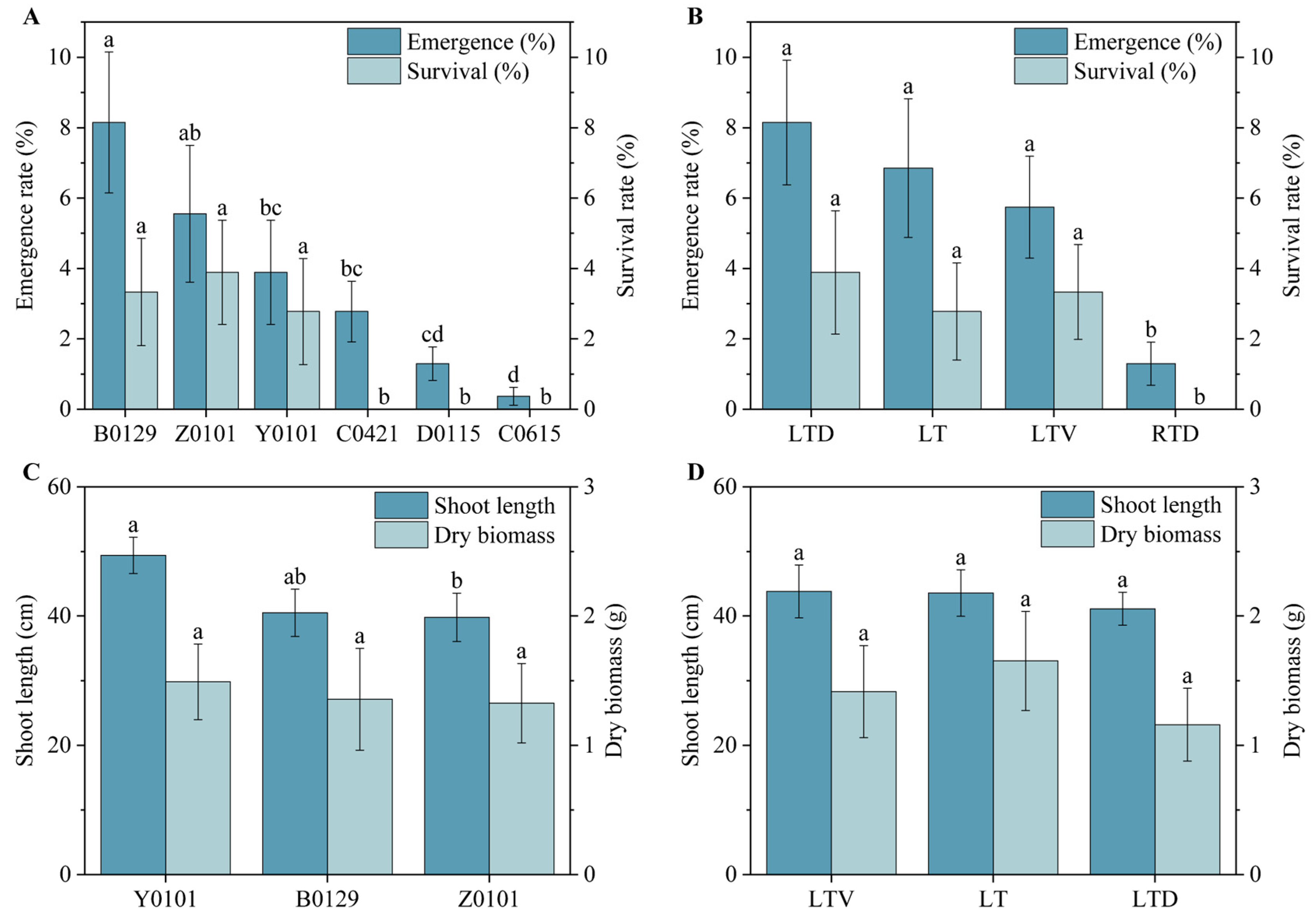

3.3. Field Performance of Miscanthus Seeds After Long-Term Storage

To evaluate the field germination of the long-stored

Miscanthus seeds, we sowed the seeds directly without prior treatment. The results were unsatisfactory, consistent with previous studies that highlighted that the direct sowing of

Miscanthus seeds was difficult to establish successfully [

29,

30]. For field planting, a “two-step” seed propagation method is recommended for

Miscanthus over direct sowing [

31]. This approach involves first cultivating seedlings in nursery beds, then strengthening them in plug trays to produce robust plantlets suited to field conditions. The seeds stored at room temperature with desiccant did not survive despite the emergence of some seedlings. The seeds stored under the three low-temperature conditions generally emerged, but only those of

M. lutarioriparius (B0129 and Y0101) and the hybrid

M. lutarioriparius ×

M. sinensis (Z0101) survived.

M. lutarioriparius and its hybrid varieties proved to be excellent biomass varieties within the

Miscanthus genus, exhibiting higher biomass yields [

32]. The higher seed viability of

M. lutarioriparius and its hybrids compared to other

Miscanthus species could provide a significant advantage in selecting

M. lutarioriparius for promotion.

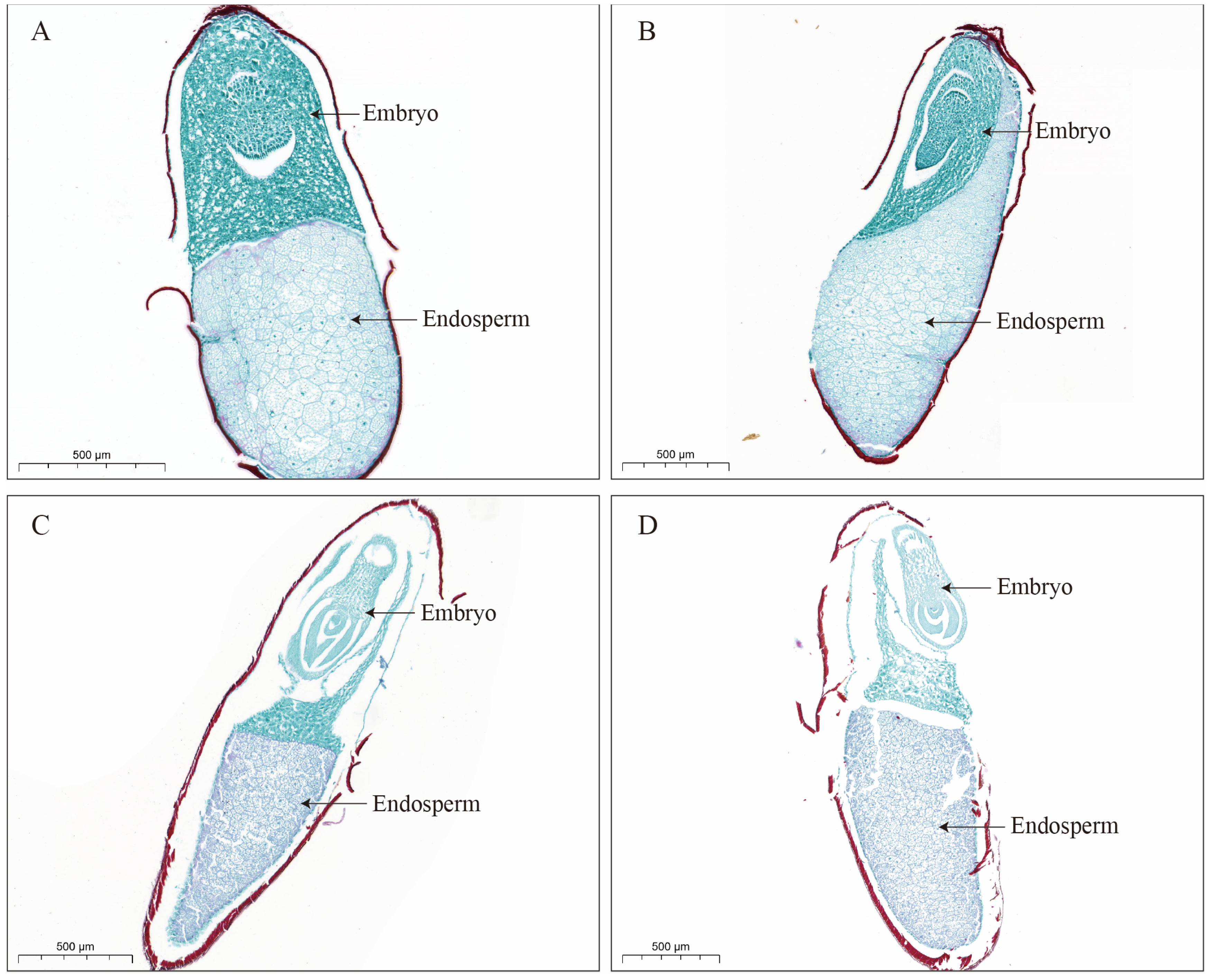

3.4. Effect of Long-Term Storage on the Cell Structure of Miscanthus Seeds

The embryo derived from a fertilized egg is the most crucial component of the seed and represents the young plant body. The cellular structure of the embryo serves as a key indicator of the physiological activity of the seed and undergoes changes as the seed ages. Among the environmental factors, relative humidity and temperature have the most direct influence on seed aging. This experiment utilized two distinct relative humidity and temperature conditions (room temperature and low temperature) for paraffin sectioning of

Miscanthus seeds. The seed cell structures demonstrated the notable differences under these conditions. The seeds stored at low temperatures maintained an intact cell structure with no apparent signs of aging, whereas the seeds stored at room temperature exhibited significant structural damage, including incomplete cell membranes and partial tissue loss in both the embryo and endosperm. As the seeds aged, the plasma membrane deteriorated, primarily due to lipid peroxidation [

33]. Increased aging led to higher concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which attacked the polyunsaturated fatty acids in membrane phospholipids. This process resulted in the breakdown of the long-chain fatty acids into smaller compounds, altering membrane permeability and causing membrane damage [

18]. Consequently, the primary cause of the failure of

Miscanthus seeds stored at room temperature to germinate was seed aging and destruction of the cellular structure.

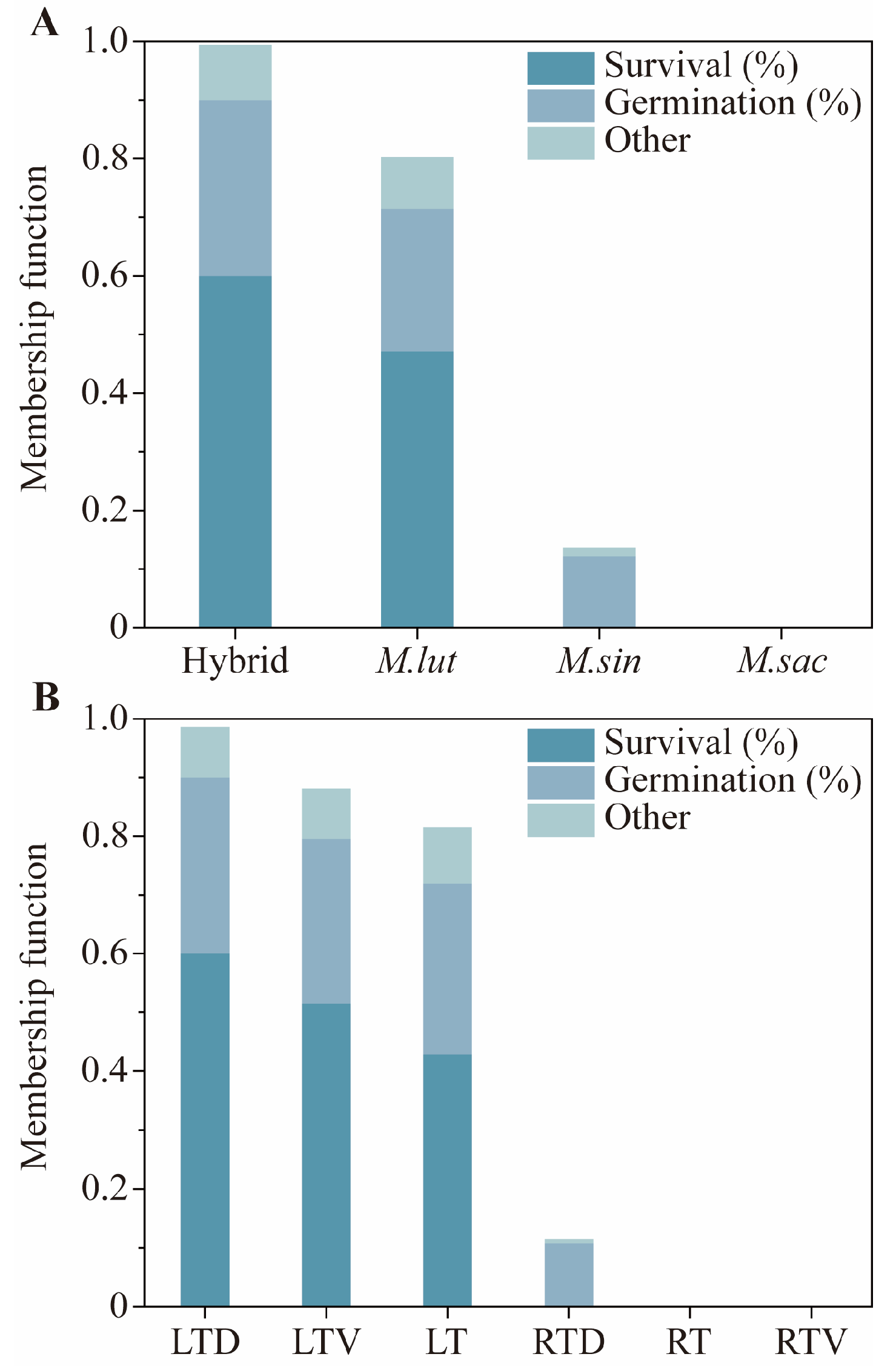

3.5. Optimal Conditions for Storing Miscanthus Seeds

To evaluate the impact of various storage conditions on Miscanthus seeds, we employed a membership function. This study aimed to provide practical guidance for the application of Miscanthus seeds, with the particular emphasis on the field survival, which has been assigned the highest weight. Although the field survival results were not entirely satisfactory, they revealed significant differences among the different storage conditions and genotypes. Additionally, the germination percentage, a primary indicator of seed quality, was also given substantial weight in the evaluation.

The results of the comprehensive evaluation indicated that the low temperature with desiccant storage was optimal for maintaining Miscanthus seeds’ vitality. This finding is significant for both seed production and long-term preservation, demonstrating that high seed vitality can be sustained using a relatively simple storage method. Although storage at −18 °C with desiccant incurs higher energy costs than other storage, it is strongly recommended for protecting high-value Miscanthus genetic resources, breeding lines, and commercial seed stocks. Producing new Miscanthus seeds is a prohibitively expensive and lengthy process, requiring a full year of dedicated land use, controlled pollination, labor-intensive harvesting, and post-harvest processing. By contrast, the energy cost of maintaining a −18 °C freezer is relatively modest. Moreover, the desiccant is not a consumable but a reusable resource. It can be regenerated by drying, thereby distributing its cost over many years. Consequently, while storage at −18 °C with desiccant has an ongoing cost, it is overwhelmingly cost-effective compared to the alternative of frequent seed regeneration. This makes the −18 °C with the desiccant method not only biologically superior but also economically imperative. To ensure the sustained viability of Miscanthus seeds, a routine monitoring program is critical. For seeds stored at −18 °C with desiccant, we recommend annual germination testing to verify the maintenance of high viability.

The evaluation also revealed the differences among genotypes. Seeds from M. lutarioriparius and its hybrids, with M. lutarioriparius as the maternal parent, exhibited superior performance, whereas M. sacchariflorus seeds performed the worst. Therefore, M. lutariparius should be prioritized as the female parent in breeding new Miscanthus varieties to cultivate strains with higher vitality and adaptability.

4. Conclusions

To promote the cultivation of Miscanthus in marginal lands, there is a significant need for Miscanthus resources. Seed propagation could offer a rapid and cost-effective alternative to the high costs of traditional rhizome propagation. However, because Miscanthus seeds lack a dormancy period, identifying the suitable storage conditions is crucial. This study developed an economical and straightforward storage method through long-term experiments: drying the Miscanthus seeds and storing them with desiccants at −18 °C to maintain the long-term viability. The seeds stored under these conditions for five years achieved the maximum average germination percentage of 75.56%, although the maximum average field survival was relatively low at 8.89%. Thus, improving the field survival remained necessary. Additionally, this study observed a significant impact of genotypes on Miscanthus seed storage. However, owing to the limited number of species studied (two Miscanthus sinensis, two Miscanthus lutarioriparius, one Miscanthus sacchariflorus, and one interspecific hybrid of Miscanthus sinensis and Miscanthus lutarioriparius), the effects of different Miscanthus species on seed storage are not fully understood.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Origin and Storage Conditions of Miscanthus Seeds

The

Miscanthus seeds utilized in this study were obtained from the

Miscanthus Resource Garden at Hunan Agricultural University in Hunan Province, China (28°11′ N, 113°4′ E). Seeds were collected from six maternal lines (

Table S3) grown in this common garden, where natural hybridization could occur. All subsequent references to species and hybrids are based on these known maternal lines. The lines included two

Miscanthus sinensis, two

Miscanthus lutarioriparius, one

Miscanthus sacchariflorus, and one interspecific hybrid (

M. sinensis ×

M. lutarioriparius). The seeds were harvested on 25 December 2016, and were then subjected to treatment and preliminary storage following the protocol developed by Chau et al. [

34]. Subsequently, the seeds were randomly selected for the pre-treatment, which included (1) assessing the initial seed viability after collection, (2) drying the seeds with desiccants, and (3) testing the seed vitality after drying. Freshly harvested seeds had a moisture content of 18.62%, compared to 12.15% after drying. This was measured by the oven method at 105 °C until constant weight was achieved. The initial tests indicated that the

Miscanthus seeds could germinate in the second test, suggesting that the

Miscanthus seeds were not recalcitrant. Therefore, storing the seeds under oxygen-rich, warm, and moist conditions, which were typically required for recalcitrant seeds, could be unnecessary.

The dry seeds were placed into the centrifuge tubes with small holes in the top cover and subjected to six different storage conditions: (1) room temperature (RT), (2) room temperature with desiccant (RTD), (3) room temperature with vacuum (RTV), (4) low temperature (LT), (5) low temperature with desiccant (LTD), and (6) low temperature with vacuum (LTV) (

Figure S2). To achieve the desired drying conditions, the centrifuge tubes containing the seeds were placed in Falcon tubes filled with silica gel pellets. For the vacuum treatment, the tubes were packed and sealed in aluminum foil bags using a vacuum sealer. Then they are transferred to a freezer at −18 °C or stored at room temperature. All the seeds were kept in the dark.

Temperature (°C) and relative humidity (%) data for the experimental site were obtained from

https://wheata.cn/ (accessed on 17 January 2024). Detailed monthly fluctuations under the ambient condition are provided in

Figure S3. Room temperature storage conditions entailed exposure to the ambient environment of the experimental site. The mean temperature ranged from 4.6 °C to 30.8 °C. Maximum temperatures commonly occurred in July and August, with peaks reaching 40.0 °C, while minimum temperatures were recorded in January and February, dropping to as low as −5.0 °C. Relative humidity was consistently high, exceeding 60% in all months except September 2019, when it dropped to 51.56%. The maximum relative humidity recorded was 89.61%.

5.2. Performance of Seed Germination During Long-Term Storage

The seed germination experiments were conducted under consistent conditions to assess the viability of the seeds after long-term storage. To prevent fungal infestation during the germination test, the seeds were disinfected with the sodium hypochlorite solution and then rinsed with distilled water. The germination experiments used the Petri dishes with the filter paper as the growth medium, and the Petri plates were sterilized by autoclaving. The samples were placed evenly on the double-layer filter paper in the culture dishes, which were then incubated in the seed incubator at 25 ± 0.5 °C with alternating light (12 h light/dark photoperiod). They were maintained in a moist environment with the daily application of distilled water. Each treatment per genotype included 30 seeds and was replicated three times to ensure statistical reliability [

35]. Germination was assessed by the presence of a visible radicle, and the germinated seeds were counted daily. The experiment was terminated if no new seeds were germinated for three consecutive days. Germination experiments were conducted in 2016, 2020 and 2021, with a focus on the later stages of storage when a substantial loss of viability was expected, to assess the long-term effectiveness of the storage methods.

5.3. Performance of Seed Establishment in the Field After Long-Term Storage

Field trials were conducted in late July 2021 at Hunan Agricultural University to evaluate the practical field establishment potential of seeds after five years of storage. The primary objective was to determine whether the viability observed in laboratory tests after extended storage translated into successful field establishment. This assessment served as the definitive test of the storage method’s practical effectiveness. The designated area was prepared for seed germination, which was divided into 108 plots, encompassing six genotypes, six storage methods, and three replications. Prior to the trial, the vegetation and litter were removed from the plots. The stored seeds from each group were randomly distributed on the plot surface, with each group consisting of 30 seeds. The regular watering every 2 d ensured the seed germination and growth. The germinated seeds were counted on the 10th day of sowing. After 60 d, all the surviving seedlings were collected, and the survival, shoot length, and dry biomass weight were measured. To determine the dry biomass weight, the seedlings were placed in a desiccator at 65 °C until a constant mass was achieved and then weighed. During the field experiment, the average highest temperature was 34.25 °C, the average lowest temperature was 25.72 °C, and total precipitation was 144.10 mm.

5.4. Paraffin Section of Long-Term Storage of Miscanthus Seeds

The paraffin sectioning was performed to examine the morphological changes in Miscanthus seeds after storage. To clearly reveal the differences in the internal structure of the seeds, we selected the seeds stored under the conditions with the highest and lowest germination percentages for these experiments. The seeds were initially rinsed with distilled water and subsequently immersed in a fixative composed of formaldehyde, acetic acid, and 50% ethanol for 24 h. Following the fixation, the seeds were subjected to a dehydration process using a graded series of ethanol solutions: 50% ethanol for 1 h, 70% for 2 h, 85% for 2 h, 95% for 1 h, and two changes of 100% ethanol for 45 min each. To achieve tissue transparency, 100% ethanol was replaced sequentially by a 1:1 mixture of 100% ethanol–dimethylbenzene, followed by dimethylbenzene, with each step lasting 1 h. The dimethylbenzene was then replaced with the 1:1 mixture of dimethylbenzene and wax, followed by three treatments with pure wax, each involving incubation in an oven at 56 °C for 4 h. The molten wax was poured into the embedding boxes, and the material was adjusted using a dissecting needle to facilitate sectioning. For the structural observations, the sections were cut using a rotary microtome and floated on the surface of a water bath set at 40 °C to flatten them. The sections were carefully transferred to the microscope slides and vertically placed in a slide holder. The slide holder was then dried in an oven at 42 °C to ensure the proper adhesion of the sections. Subsequently, the paraffin sections were deparaffinized through two treatments with xylene, each lasting 20 min. The slides were immersed in a graded ethanol series (xylene–ethanol 1:1; 100%, 95%, 85%, and 70% ethanol for 30 min each). The staining was performed using Safranine O-Fast Green Stain, according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol (Solarbio Life Science, Beijing, China). Multiple seed samples were prepared and imaged microscopically. The micrographs shown are representative of the observations.

5.5. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were analyzed using the general linear model (GLM) in Origin (version 2025) software. The statistical significance of differences between means was assessed using the Duncan test, with significant results reported at the p < 0.05 level. Given that a single trait could often fail to fully reflect the storage performance of Miscanthus seeds, this study employed a membership function approach for a comprehensive evaluation of seeds stored for five years. This method normalizes the original data of each seed vigor trait to a relative scale from 0 (poorest performance) to 1 (best performance), resulting in a dimensionless membership value for each trait. To address the varying importance of different traits, a weighted sum of the membership values was then calculated. The field survival, as a decisive indicator of crop establishment success, was assigned a weight of 0.6. The indoor germination percentage, the primary measure of seed quality, was assigned a weight of 0.3. The remaining four traits were collectively assigned a weight of 0.1 to reflect their supportive role in the overall evaluation system. The final composite evaluation score was derived from these weighted membership values.