Identification of Spike Length Gene and Development of KASP Markers in Wheat

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenotypic Identification and Genetic Analysis

2.2. BSA-Seq Analysis

| Sample | Aikang 58 | Long Spike Mutants | Normal Offspring Mixed Pool | Long Spike Offspring Pool |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Reads Number | 133,225,654 | 124,622,072 | 141,320,642 | 158,423,946 |

| Clean Reads Number | 133,225,650 | 124,622,072 | 141,320,642 | 158,423,946 |

| Raw Bases (bp) | 19,983,848,100 | 18,693,310,800 | 21,198,096,300 | 23,763,591,900 |

| Clean Bases (bp) | 19,903,818,088 | 18,614,137,400 | 21,098,284,286 | 23,641,511,070 |

| Effective Rate (%) | 99.60 | 99.58 | 99.53 | 99.49 |

| Q20 (%) | 98.86 | 98.86 | 98.88 | 98.90 |

| Q30 (%) | 96.86 | 96.84 | 96.90 | 96.98 |

| Align reads number | 132,849,145 | 124,431,656 | 140,910,807 | 158,167,511 |

| Align rate (%) | 99.72 | 99.85 | 99.71 | 99.84 |

| Target region size (Mb) | 236.64 | 237.91 | 232.73 | 231.11 |

| Target region coverage Rate (%) | 96.88 | 97.53 | 98.56 | 98.58 |

| Depth (X) | 50.09 | 49.17 | 53.26 | 61.15 |

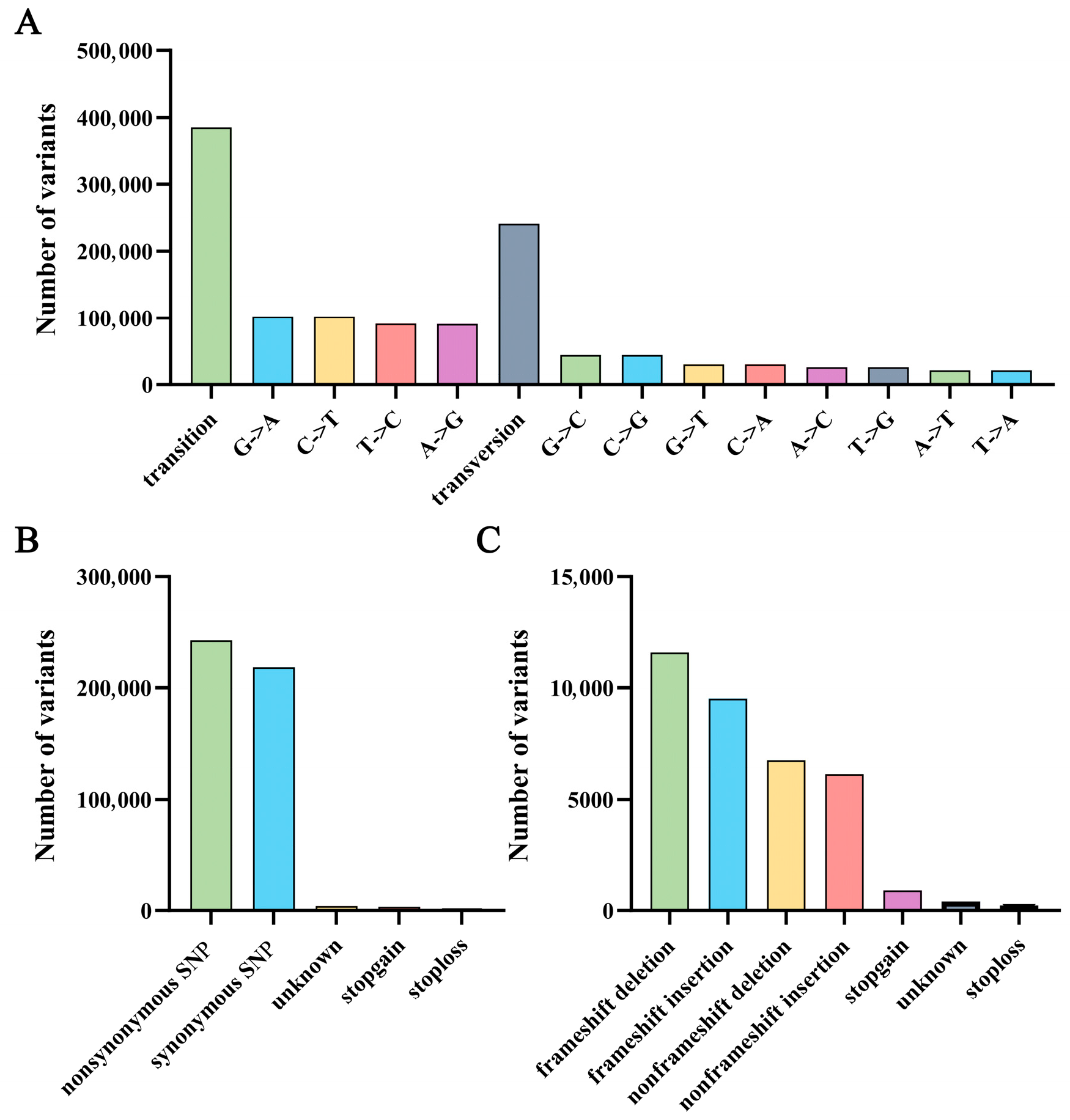

2.3. Mutation Site Detection

2.4. SNP-Index Association Analysis

2.5. Euclidean Distance Analysis

2.6. Target Trait Region Mapping

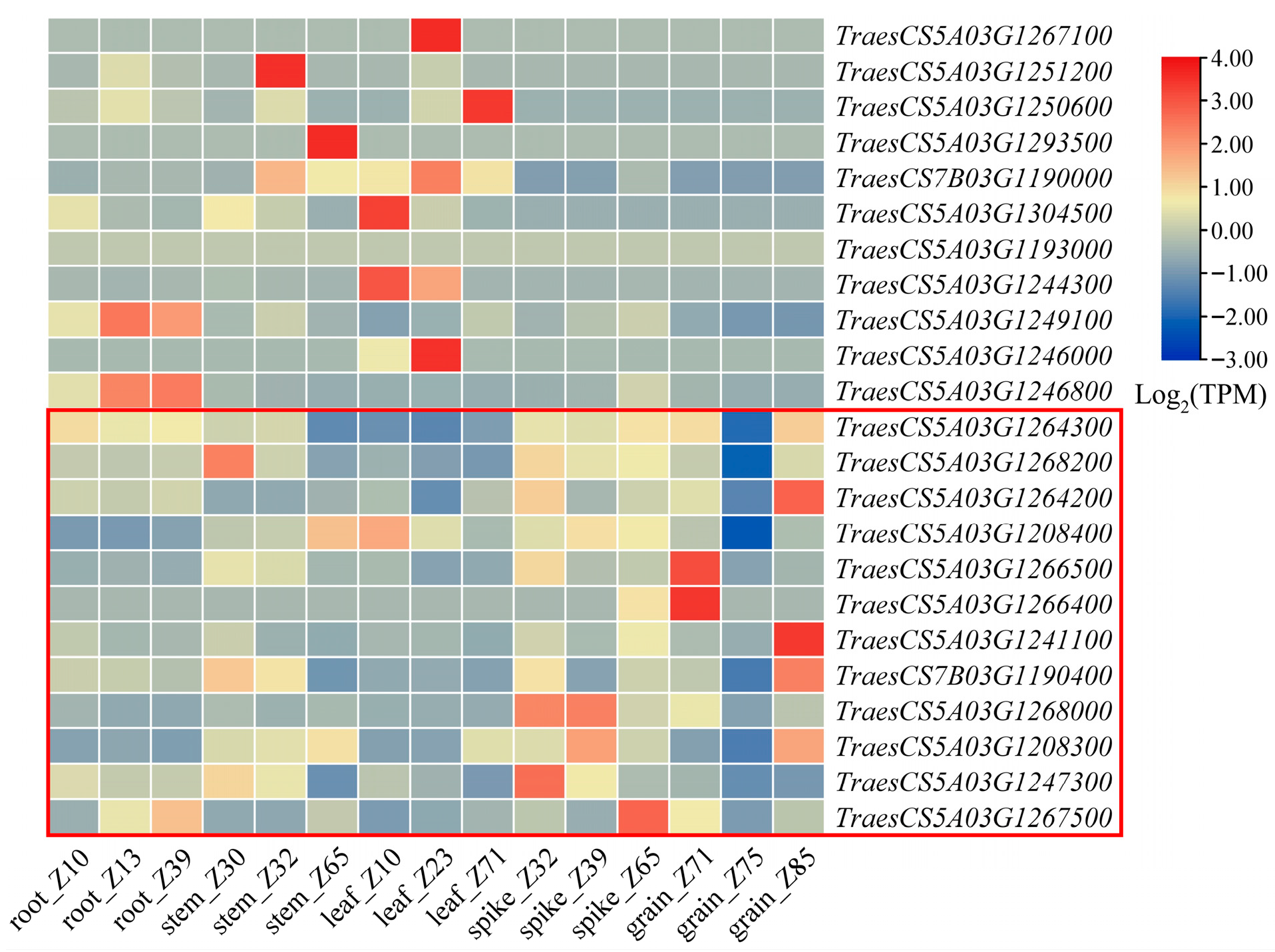

2.7. Candidate Gene Prediction and Expression Analysis

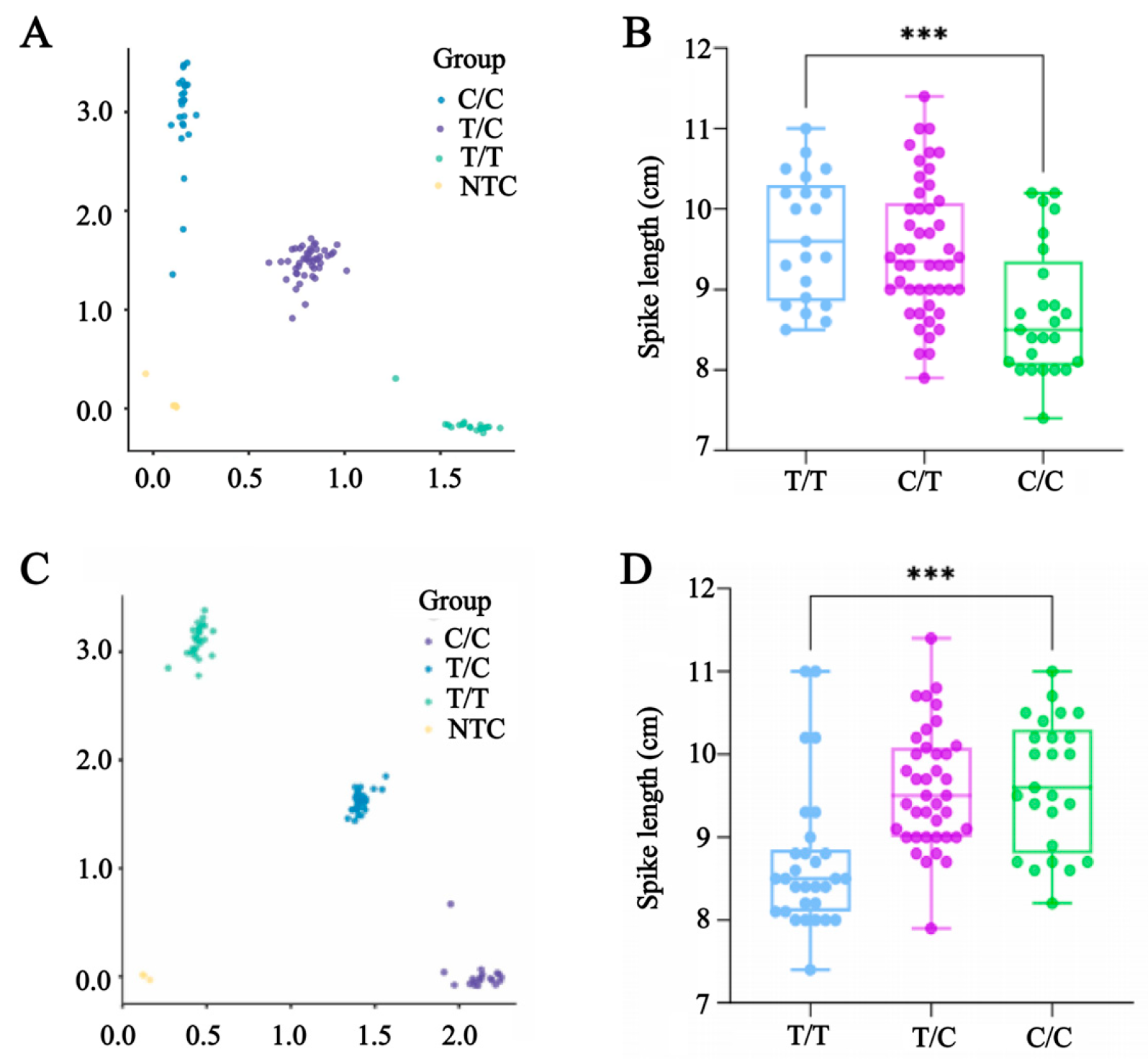

2.8. KASP Marker Development and Validation

3. Discussion

3.1. Identification of Key Spike-Length-Related Genetic Loci Relevant to Increasing Wheat Yields

3.2. Analysis of Wheat Spike-Length-Related Candidate Genomic Regions

3.3. Candidate Gene Expression and Function

3.4. Development of KASP Markers for Long Spikes and Screening of Effective Genotyping Markers

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Phenotypic Data Collection

4.2. BSA-Seq

4.2.1. DNA Extraction and Mixed Pool Construction

4.2.2. Reference Genome Alignment and SNP Detection

4.3. Candidate Region Analysis and Gene Identification

4.4. KASP Marker Development

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, H.; Li, T.; Hou, J.; Yin, X.; Wang, Y.; Si, X.; Rehman, S.U.; Zhuang, L.; Guo, W.; Hao, C.; et al. TaWUS-like-5D affects grain weight and filling by inhibiting the expression of sucrose and trehalose metabolism-related genes in wheat grain endosperm. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 2018–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiferaw, B.; Smale, M.; Braun, H.J.; Duveiller, E.; Reynolds, M.; Muricho, G. Crops that feed the world 10. Past successes and future challenges to the role played by wheat in global food security. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qiao, L.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Liu, C.; Guo, H.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, S.; Chang, L.; Chen, F.; et al. Genetic incorporation of the favorable alleles for three genes associated with spikelet development in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 892642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hegarty, J.; Padilla, M.; Tricoli, D.M.; Dubcovsky, J.; Debernardi, J.M. Manipulation of the microRNA172–AP2L2 interaction provides precise control of wheat and triticale plant height. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z. Ring the yield: Regulation of spike architecture by an E3 ubiquitin ligase in crops. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 4889–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wang, C.; Cai, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F.; Shi, X.; Cheng, J.; Sun, H.; Wu, Y.; et al. Characterization of a wheat stable QTL for spike length and its genetic effects on yield-related traits. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, V.; Uauy, C.; Chen, Y. Identification of a novel SNP in the miR172 binding site of Q homoeolog AP2L–D5 is associated with spike compactness and agronomic traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 137, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; She, M.; Yang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhai, S.; Balotf, S.; Zhao, Y.; Anwar, M.; Alhabbar, Z.; et al. Yield-related QTL clusters and the potential candidate genes in two wheat DH populations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kulwal, P.L.; Balyan, H.S.; Gupta, P.K. QTL Mapping for Yield and Yield Contributing Traits in Two Mapping Populations of Bread Wheat. Mol. Breed. 2007, 19, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.M.; Tamhankar, S.A.; Oak, M.D.; Raut, A.L.; Honrao, B.K.; Rao, V.S.; Misra, S.C. Mapping of QTL for agronomic traits and kernel characters in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.). Euphytica 2013, 190, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, R.; Wang, M.; Li, L.; Yan, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, A.; Su, Z.; et al. Identification and characterization of QTL for spike morphological traits, plant height and heading date derived from the D genome of natural and resynthetic allohexaploid wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, C.H.; Zhao, X.F.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Z.P.; Ding, L.; Pu, Z.E.; Ma, J.; Jiang, Q.-T.; Chen, G.-Y.; Wang, J.-R.; et al. Mapping and characterization of major QTL for spike traits in common wheat. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, S.; Lin, F.; Kong, Z.; Tian, D.; Luo, Q. Molecular genetic analysis of five spike-related traits in wheat using RIL and immortalized F2 populations. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2007, 277, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Gao, A. QTL mapping of yield-related traits in the wheat germplasm 3228. Euphytica 2011, 177, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tang, S.; Zhan, Q.; Hou, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Feng, Q.; Zhou, C.; Lyu, D.; Cui, L.; et al. Dissecting a heterotic gene through Graded Pool-Seq mapping informs a rice-improvement strategy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Huang, S.; Mu, J.; Zeng, Q.; Huang, L.; Han, D.; Kang, Z. Saturation mapping of a major effect QTL for stripe rust resistance on wheat chromosome 2B in cultivar Napo 63 using SNP genotyping arrays. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneeberger, K.; Weigel, D. Fast-forward genetics enabled by new sequencing technologies. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lu, J.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Ao, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, L. Identification and validation of a major quantitative trait locus for spike length and compactness in the wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) line Chuanyu12D7. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1186183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Xu, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, Q.; Liu, X.; Liao, S.; Feng, B.; Wang, T. Identification of a major and stable QTL on chromosome 5A confers spike length in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Mol. Breed. 2021, 41, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, E.; Cheng, S.; Ma, A. Identification of molecular markers and candidate regions associated with grain number per spike in Pubing3228 using SLAF-BSA. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1361621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Feng, B.; Xu, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ji, G.; Liao, S.; Gao, P.; Wang, T. Genetic Dissection of Three Major Quantitative Trait Loci for Spike Compactness and Length in Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 882655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wen, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, S.; He, Z.; Rasheed, A.; Jin, H.; Zhang, C.; Yan, J.; et al. Genetic architecture of grain yield in bread wheat based on genome-wide association studies. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, X.; Pu, X.; Pan, Z.; et al. High-resolution detection of quantitative trait loci for seven important yield-related traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using a high-density SLAF-seq genetic map. BMC Genom. Data 2022, 23, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Kumar, J.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, S. Multi-locus genome-wide association mapping for spike-related traits in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiang, M.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Cheng, X.; Li, H.; Zeng, Q. Development and application of the GenoBaits Wheat SNP 16K array to accelerate wheat genetic research and breeding. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Feng, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Xiao, S.; Ni, Z.; Sun, Q. QTL analysis of spike morphological traits and plant height in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using a high-density SNP and SSR-based linkage map. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, P.; Chen, W.; Hao, Y.; Ma, X.; Xu, S.; Jia, J.; Kong, L.; et al. QTL mapping for yield-related traits in wheat based on four RIL populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiong, H.; Guo, H.; Li, Y.; Xie, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gu, J.; Zhao, S.; Ding, Y.; et al. Identification of the Q gene playing a role in spike morphology variation in wheat mutants and its regulatory network. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 807731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shi, Z.; Ma, F.; Xu, Y.; Han, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; An, D. Identification and validation of plant height, spike length and spike compactness loci in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Batool, A.; Xu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Lin, X.; Bie, X.; et al. TabHLH27 orchestrates root growth and drought tolerance to enhance water use efficiency in wheat. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1295–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Fu, X.; Zhou, N.; Liu, M.; Bai, S.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, R.; Li, S.; Zhang, D. Identification and map-based cloning of an EMS-induced mutation in wheat gene TaSP1 related to spike architecture. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xue, S.; Jia, J.; Zhao, G.; Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Kong, C.; Yan, D.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; et al. The wheat transcription factor Q functions in gibberellin biosynthesis and signaling and regulates height and spike length. Plant Cell. 2025, 37, koaf183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Pang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H.; Li, G.; Wu, Y.; et al. qSL2B/TaeEF1A regulates spike development and grain number in wheat. Crop J. 2025, 13, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobe, B.; Kajava, A.V. The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001, 11, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, J.; Walshe, K.; Alsbury, S.; Hokamp, K.; O’Keeffe, S.; Okafuji, T.; Miller, S.F.; Tear, G.; Mitchell, K.J. The extracellular leucine-rich repeat superfamily; a comparative survey and analysis of evolutionary relationships and expression patterns. BMC Genom. 2007, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Song, Q.; Shan, S.; Wang, J.; Ma, S.; Song, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, G.; Niu, N. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of TUA and TUB genes in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) during its development. Plants 2022, 11, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Dai, Y.; Cui, S.; Ma, L. Histone H2B monoubiquitination in the chromatin of FLOWERING LOCUS C regulates flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2586–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Jiang, D.; Wang, Y.; Bachmair, A.; He, Y. Repression of the floral transition via histone H2B monoubiquitination. Plant J. 2009, 57, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yin, Y.; Liu, X.; Tong, S.; Xing, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pudake, R.N.; Izquierdo, E.M.; Peng, H.; Xin, M.; et al. The E3 ligase TaSAP5 alters drought stress responses by promoting the degradation of DRIP proteins. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 1878–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, V.; Majee, M. Emerging roles of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway in enhancing crop yield by optimizing seed agronomic traits. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 1805–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Hu, T.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, J.; Hao, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, T. TaGW2L, a GW2-like RING finger E3 ligase, positively regulates heading date in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Crop J. 2022, 10, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Xi, Y.; Wang, J.; Mao, X.; Jing, R. RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase gene TaAIRP2-1B controls spike length in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 5014–5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wu, M.; Pei, W.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, S. Quantitative phosphoproteomic profiling of fiber differentiation and initiation in a fiberless mutant of cotton. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, J.; Wang, F.; Ji, G.; Yang, L.; Feng, B.; Wang, T. A genome-wide association study of wheat spike related traits in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Hu, X.; Ma, C.; Jiang, H.; Xie, C.; Gao, Y.; Ding, G.; Zhao, C.; et al. Genome-wide association study and genomic selection of spike-related traits in bread wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, P.; Liang, X.; Zhao, H.; Feng, B.; Xu, E.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y. Identification of the quantitative trait loci controlling spike-related traits in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Planta 2019, 250, 1967–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porebski, S.; Bailey, L.G.; Baum, B.R. Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 1997, 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouard, J.S.; Schenkel, F.; Marete, A.; Bissonnette, N. The GATK joint genotyping workflow is appropriate for calling variants in RNA-seq experiments. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, M.; Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SNPs Mutation Region | Number of Variants | InDels Mutation Region | Number of Variants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exonic | 469,329 | Exonic | 35,361 |

| Intronic | 117,672 | Intronic | 38,173 |

| UTR3 | 13,059 | UTR3 | 4234 |

| UTR5 | 10,178 | UTR5 | 4515 |

| Upstream | 6972 | Upstream | 2495 |

| Downstream | 5248 | Downstream | 1559 |

| Upstream; downstream | 2979 | Upstream; downstream | 955 |

| Splicing | 925 | Splicing | 610 |

| Exonic; splicing | 125 | Exonic; splicing | 32 |

| UTR5; UTR3 | 19 | UTR5; UTR3 | 8 |

| Chrom | Start | End | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5A | 673,837,810 | 674,334,747 | 496,938 |

| 5A | 680,382,639 | 682,026,829 | 1,644,191 |

| 5A | 682,106,425 | 682,770,497 | 664,073 |

| 5A | 691,443,224 | 696,644,520 | 5,201,297 |

| 5A | 700,302,103 | 701,184,634 | 882,532 |

| 5A | 709,603,814 | 709,631,542 | 27,729 |

| 5A | 711,943,509 | 713,264,094 | 1,320,586 |

| 7B | 714,825,625 | 715,608,889 | 783,265 |

| 7B | 717,391,811 | 717,688,886 | 297,076 |

| 7B | 727,435,274 | 727,441,287 | 6014 |

| Chrom | Start | End | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5A | 673,837,810 | 674,334,747 | 496,938 |

| 5A | 680,382,639 | 682,026,829 | 1,644,191 |

| 5A | 682,106,425 | 682,770,497 | 664,073 |

| 5A | 691,500,001 | 695,000,001 | 3,500,001 |

| 5A | 700,302,103 | 701,184,634 | 882,532 |

| 5A | 709,603,814 | 709,631,542 | 27,729 |

| 5A | 712,000,001 | 713,264,094 | 1,264,094 |

| 7B | 714,825,625 | 715,608,889 | 783,265 |

| 7B | 717,391,811 | 717,688,886 | 297,076 |

| Gene ID | Gene Function Annotation |

|---|---|

| TraesCS5A03G1193000 | Peptidase S1, PA clan |

| TraesCS5A03G1208300 | Protein kinase domain |

| TraesCS5A03G1208400 | PAZ domain |

| TraesCS5A03G1241100 | Protein PAIR1 |

| TraesCS5A03G1244300 | TIFY/JAZ family |

| TraesCS5A03G1246000 | Helix-loop-helix DNA-binding domain superfamily |

| TraesCS5A03G1246800 | ABC transporter A |

| TraesCS5A03G1247300 | Tubulin |

| TraesCS5A03G1249100 | Transcription factor GRAS |

| TraesCS5A03G1250600 | Bifunctional inhibitor/plant lipid transfer protein/seed storage helical domain |

| TraesCS5A03G1251200 | Bifunctional inhibitor/plant lipid transfer protein/seed storage helical domain superfamily |

| TraesCS5A03G1264200 | Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase-related |

| TraesCS5A03G1264300 | PLAC8 motif-containing protein |

| TraesCS5A03G1266400 | Aspartic peptidase A1 family |

| TraesCS5A03G1266500 | Aspartic peptidase A1 family |

| TraesCS5A03G1267100 | Leucine-rich repeat |

| TraesCS5A03G1267500 | Leucine-rich repeat domain superfamily |

| TraesCS5A03G1268000 | RING-type E3 ubiquitin transferase, |

| TraesCS5A03G1268200 | F-box domain-containing protein |

| TraesCS5A03G1293500 | ACT domain |

| TraesCS5A03G1304500 | ABC transporter-like |

| TraesCS7B03G1190000 | Alpha/Beta hydrolase fold |

| TraesCS7B03G1190400 | Lysine methyltransferase |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, T.; Meng, L.; Ji, C.; Wang, Z.; Cao, H.; Sun, R.; Xu, K.; Meng, X.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y. Identification of Spike Length Gene and Development of KASP Markers in Wheat. Plants 2025, 14, 3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233703

Jiang T, Meng L, Ji C, Wang Z, Cao H, Sun R, Xu K, Meng X, Yang X, Zhao Y. Identification of Spike Length Gene and Development of KASP Markers in Wheat. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233703

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Tiantian, Lingpeng Meng, Chao Ji, Zehui Wang, Huiwen Cao, Ruoxi Sun, Ke Xu, Xianghai Meng, Xueju Yang, and Yong Zhao. 2025. "Identification of Spike Length Gene and Development of KASP Markers in Wheat" Plants 14, no. 23: 3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233703

APA StyleJiang, T., Meng, L., Ji, C., Wang, Z., Cao, H., Sun, R., Xu, K., Meng, X., Yang, X., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Identification of Spike Length Gene and Development of KASP Markers in Wheat. Plants, 14(23), 3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233703