Exploration of the Donors and Specific Genes of B Subgenome in Perilla frutescens Based on Genomic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

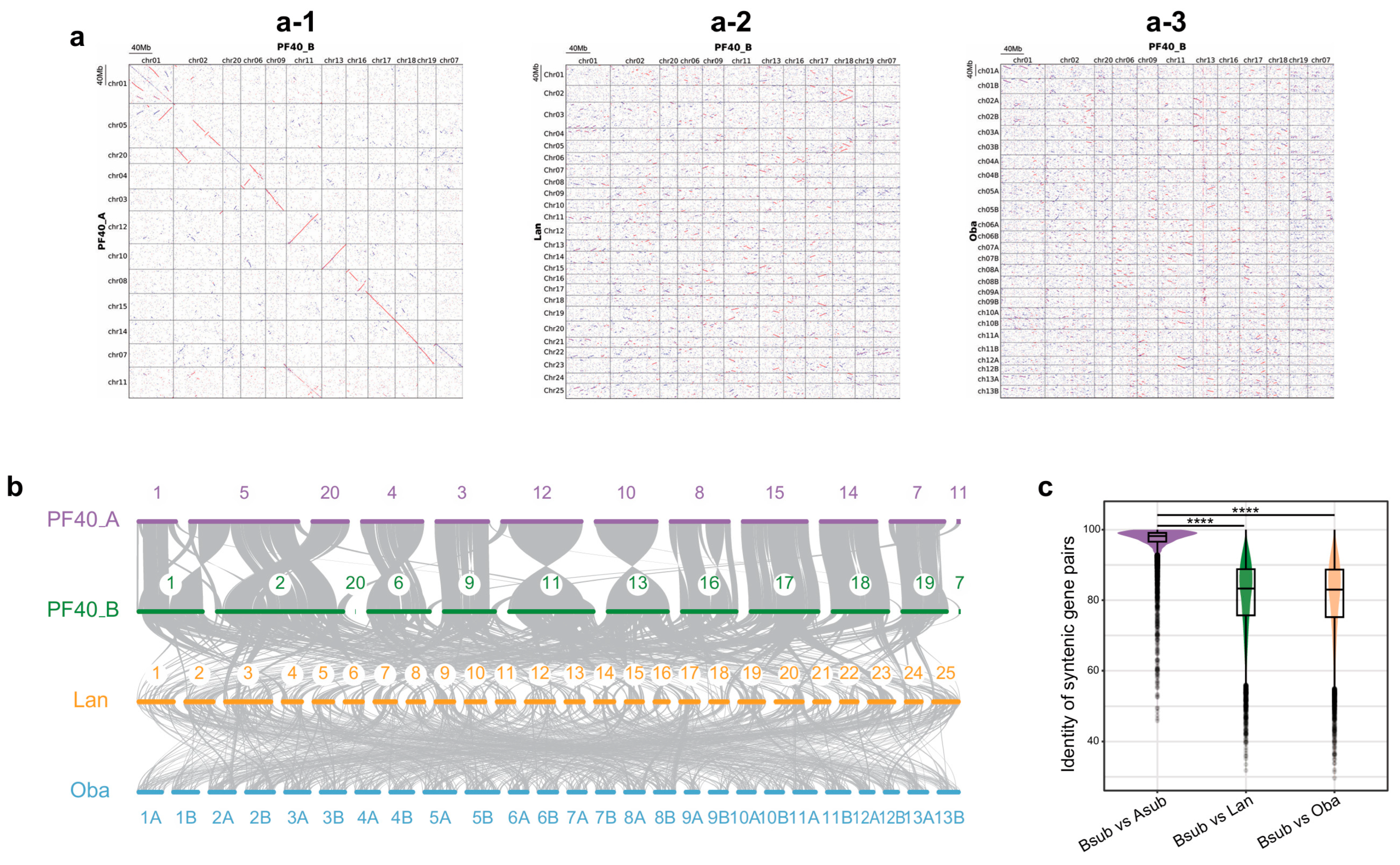

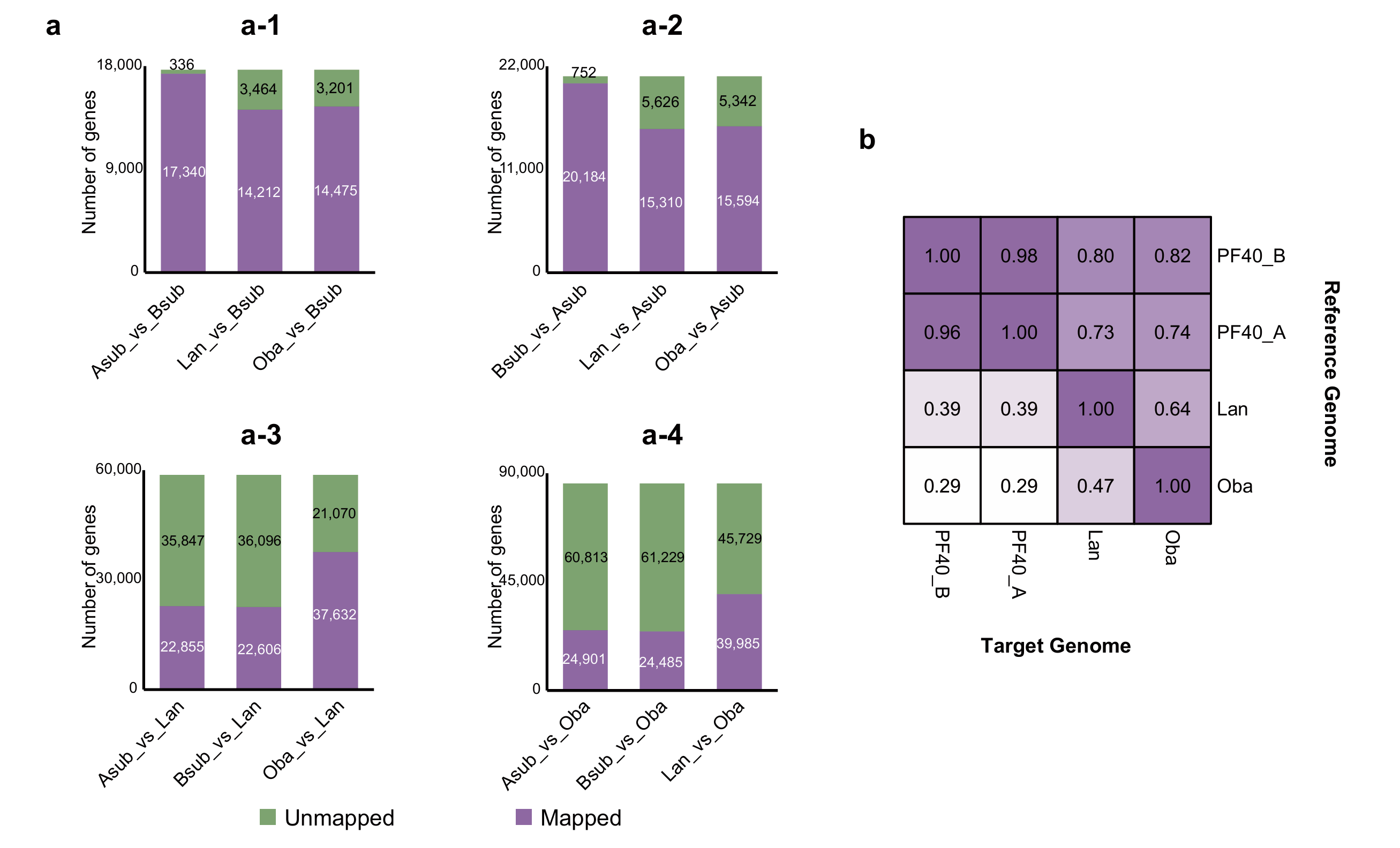

2.1. Analysis of Protein Sequence Similarity Between BB and Its Related Species

2.2. Analysis of Similarity of Gene Structures Between BB and Its Related Species

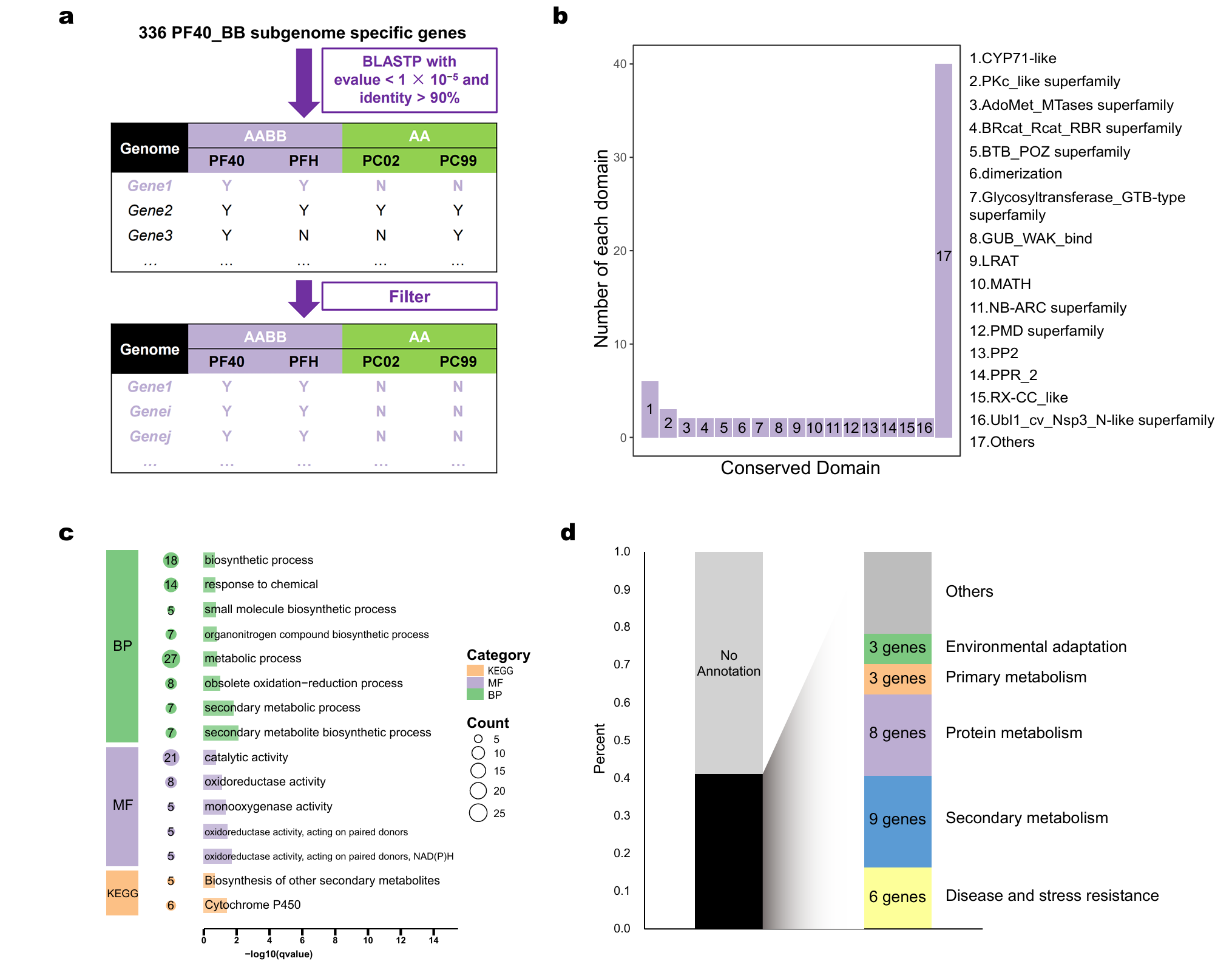

2.3. Screening and Functional Annotation of BB Progenitor-Specific Genes

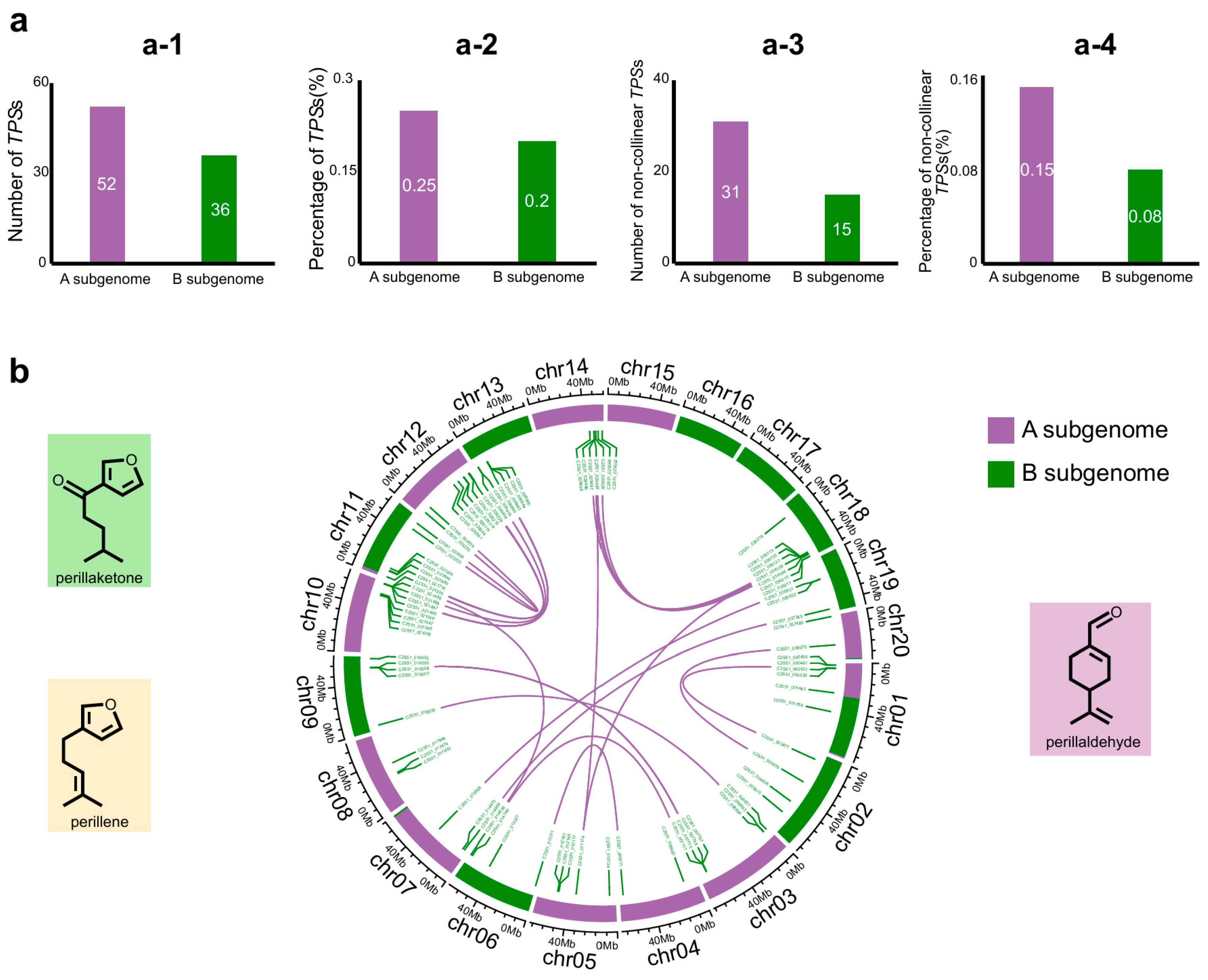

2.4. Asymmetric Distribution of TPS Families Between Subgenomes

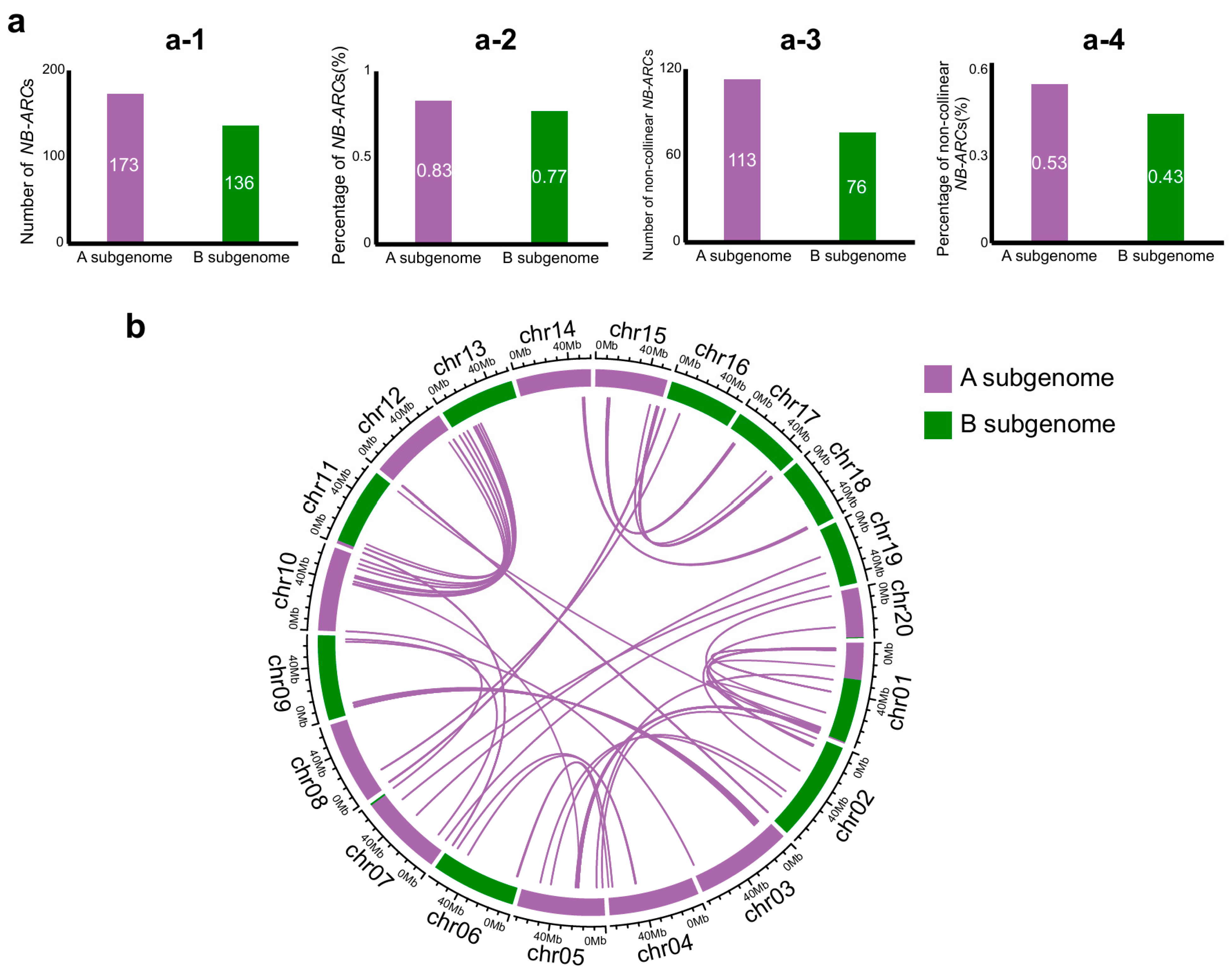

2.5. Asymmetric Distribution of NB-ARC Families Between Subgenomes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Genomic Data

4.2. Collinearity Analysis

4.3. Analysis of Gene Structural Similarity

4.4. Enrichment Analysis and Annotation of Genes

4.5. Identification and Collinearity Analysis of the TPS Family

4.6. Identification and Collinearity Analysis of the NB-ARC Family

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.-L. The vegetables of ancient China. Econ. Bot. 1969, 23, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeven, A.; De Wet, J.M. Dictionary of Cultivated Plants and Their Regions of Diversity Excluding Most Ornamentals, Forest Trees and Lower Plants; Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nitta, M.; Lee, J.K.; Kang, C.W.; Katsuta, M.; Yasumoto, S.; Liu, D.; Nagamine, T.; Ohnishi, O. The Distribution of Perilla Species. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2005, 52, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, G.; Yuba, A.; Kojima, T.; Tabata, M. Chemotaxonomic and cytogenetic studies on Perilla frutescens var. citriodora (‘Lemon Egoma’). Nat. Med. 1994, 48, 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, M.; Honda, G. Geraniol synthases from perilla and their taxonomical significance. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, Q.; Leng, L.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.; Shi, Y.; Ning, Z.; Chen, S. Incipient diploidization of the medicinal plant Perilla within 10,000 years. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Kato, H.; Oka, Y. Phylogenetic analysis of Japanese Perilla species by using DNA polymorphisms. Nat. Med. 1998, 52, 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto, N.; Korin, M.; Ito, M. Geraniol and linalool synthases from wild species of perilla. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, Y.; Ito, M. Investigation of microsatellite loci for the identification of registered varieties of Perilla frutescens and a discussion on the ancestor species of P. frutescens. J. Nat. Med. 2023, 77, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Honda, G. A taxonomic study of Japanese wild Perilla (Labiatae). J. Phytogeoer. Taxon. 1996, 44, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, H. Studies on Folium perillae. VI. Constituent of essential oils and evaluation of genus Perilla. Yakugaku Zasshi J. Pharm. Soc. Jpn. 1970, 90, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, L.; Qianrong, C. Essential oil variations in different Perilla L. accessions: Chemotaxonomic implications. Plant Syst. Evol. 2009, 281, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Ohnishi-Kameyama, M.; Nagamine, T.; Yoshida, M. Essential oil variation of cultivated and wild Perilla analyzed by GC/MS. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2006, 34, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-L.; Guo, B.-L.; Zhang, C.-W.; Zhang, F.; Tian, J.; Bai, X.-L.; Zhang, S.-N. Perilla resources of China and essential oil chemotypes of Perilla leaves. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2016, 41, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Kiuchi, F.; Yang, L.L.; Honda, G. Perilla citriodora from Taiwan and its phytochemical characteristics. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 23, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, N.; Gong, Z.; Du, H. High-quality genome of allotetraploid Avena barbata provides insights into the origin and evolution of B subgenome in Avena. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 1515–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Yuan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Li, L.; Peng, J.; Zhang, J.; Fan, X.; Jiang, C.; Sha, L.-N.; Wang, Z. Analysis of allohexaploid wheatgrass genome reveals its Y haplome origin in Triticeae and high-altitude adaptation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boachon, B.; Buell, C.R.; Crisovan, E.; Dudareva, N.; Garcia, N.; Godden, G.; Henry, L.; Kamileen, M.O.; Kates, H.R.; Kilgore, M.B.; et al. Phylogenomic mining of the mints reveals multiple mechanisms contributing to the evolution of chemical diversity in Lamiaceae. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. Phylogenomic analyses revealed widely occurring hybridization events across Elsholtzieae (Lamiaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2024, 198, 108112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.P.; Vaillancourt, B.; Wood, J.C.; Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Soltis, D.E.; Buell, C.R.; Soltis, P.S. Chromosome-scale genome assembly of the ‘Munstead’ cultivar of Lavandula angustifolia. BMC Genom. Data 2023, 24, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Abu-Abied, M.; Milavski, R.; Adler, C.; Shachter, A.; Kahane-Achinoam, T.; Melnik-Ben-Gera, H.; Davidovich-Rikanati, R.; Powell, A.F.; Chaimovitsh, D.; et al. Chromosome-level assembly of basil genome unveils the genetic variation driving Genovese and Thai aroma types. Plant J. 2025, 121, e17224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumate, A.; Salzberg, S.L. Liftoff: Accurate mapping of gene annotations. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 1639–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Sakamoto, M.; Tanizawa, Y.; Mochizuki, T.; Matsushita, S.; Kato, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Okuhara, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Bono, H. A highly contiguous genome assembly of red perilla (Perilla frutescens) domesticated in Japan. DNA Res. 2023, 30, dsac044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mau, C.J.D.; Karp, F.; Ito, M.; Honda, G.; Croteau, R.B. A candidate cDNA clone for (-)-limonene-7-hydroxylase from Perilla frutescens. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Ito, M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a Perilla frutescens cytochrome P450 enzyme that catalyzes the later steps of perillaldehyde biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 2017, 134, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupien, S.; Karp, F.; Wildung, M.; Croteau, R. Regiospecific cytochrome P450 limonene hydroxylases from mint (Mentha) species: cDNA Isolation, characterization, and functional expression of (−)-4S-limonene-3-hydroxylase and (−)-4S-limonene-6-hydroxylase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 368, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampranis, S.C.; Ioannidis, D.; Purvis, A.; Mahrez, W.; Ninga, E.; Katerelos, N.A.; Anssour, S.; Dunwell, J.M.; Degenhardt, J.; Makris, A.M.; et al. Rational conversion of substrate and product specificity in a Salvia monoterpene synthase: Structural insights into the evolution of terpene synthase function. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1994–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ooijen, G.; Mayr, G.; Kasiem, M.M.; Albrecht, M.; Cornelissen, B.J.; Takken, F.L. Structure–function analysis of the NB-ARC domain of plant disease resistance proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 1383–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G.B.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Sessa, G. Understanding the functions of plant disease resistance proteins. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2003, 54, 23–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Qu, M.; Rybicki, N.; Dodd, L.L.; Min, J.; Chen, Y.; Gao, L. Genomic resequencing unravels species differentiation and polyploid origins in the aquatic plant genus Trapa. Plant J. 2025, 123, e70463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Jiao, B.; Yang, Y.; Shan, L.; Li, T.; Li, X.; Xi, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. WGDI: A user-friendly toolkit for evolutionary analyses of whole-genome duplications and ancestral karyotypes. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Krishnakumar, V.; Zeng, X.; Xu, Z.; Taranto, A.; Lomas, J.S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yim, W.C.; et al. JCVI: A versatile toolkit for comparative genomics analysis. iMeta 2024, 3, e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R. BEDTools: The swiss-army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2014, 47, 11.12.1–11.12.34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Jose da Costa Gonzales, L.; Bowler-Barnett, E.H.; Rice, D.L.; Kim, M.; Wijerathne, S.; Luciani, A.; Kandasaamy, S.; Luo, J.; Watkins, X.; et al. The UniProt website API: Facilitating programmatic access to protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W547–W553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Gu, L.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M.; Brors, B. Circlize implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2811–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Wei, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Z.; Wei, J. Exploration of the Donors and Specific Genes of B Subgenome in Perilla frutescens Based on Genomic Analysis. Plants 2025, 14, 3698. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233698

Li Z, Wang B, Wei W, Liu Y, Wang Q, Gao Z, Wei J. Exploration of the Donors and Specific Genes of B Subgenome in Perilla frutescens Based on Genomic Analysis. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3698. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233698

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhaoyuan, Bin Wang, Wei Wei, Yang Liu, Qiuling Wang, Zhihui Gao, and Jianhe Wei. 2025. "Exploration of the Donors and Specific Genes of B Subgenome in Perilla frutescens Based on Genomic Analysis" Plants 14, no. 23: 3698. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233698

APA StyleLi, Z., Wang, B., Wei, W., Liu, Y., Wang, Q., Gao, Z., & Wei, J. (2025). Exploration of the Donors and Specific Genes of B Subgenome in Perilla frutescens Based on Genomic Analysis. Plants, 14(23), 3698. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233698