Allelopathic Effect of the Invasive Species Acacia dealbata Link and Hakea decurrens R.Br., subsp. physocarpa on Native Mediterranean Scrub Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Allelopathic Effect of Aqueous Extracts from Invasive Species on Native Mediterranean Species

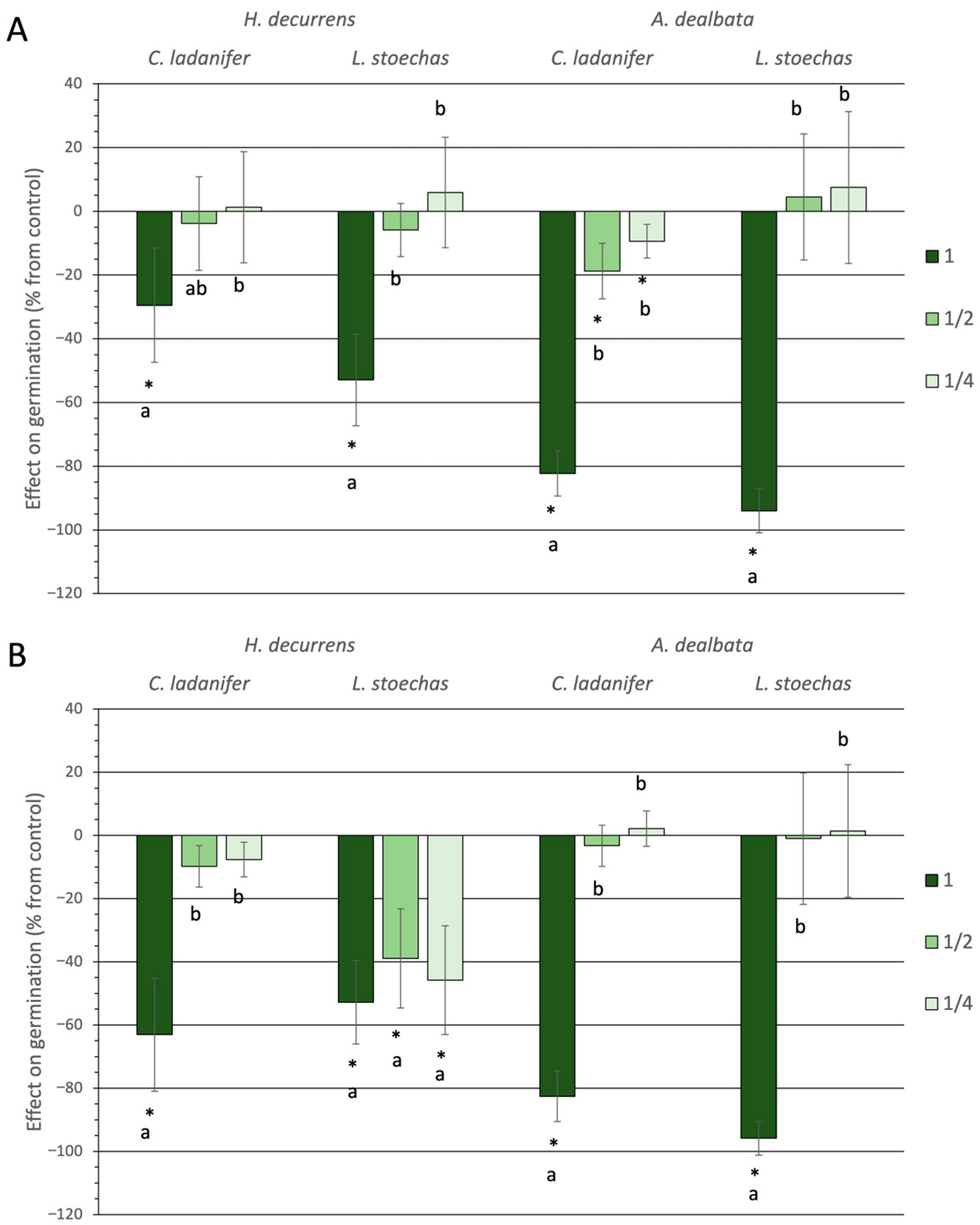

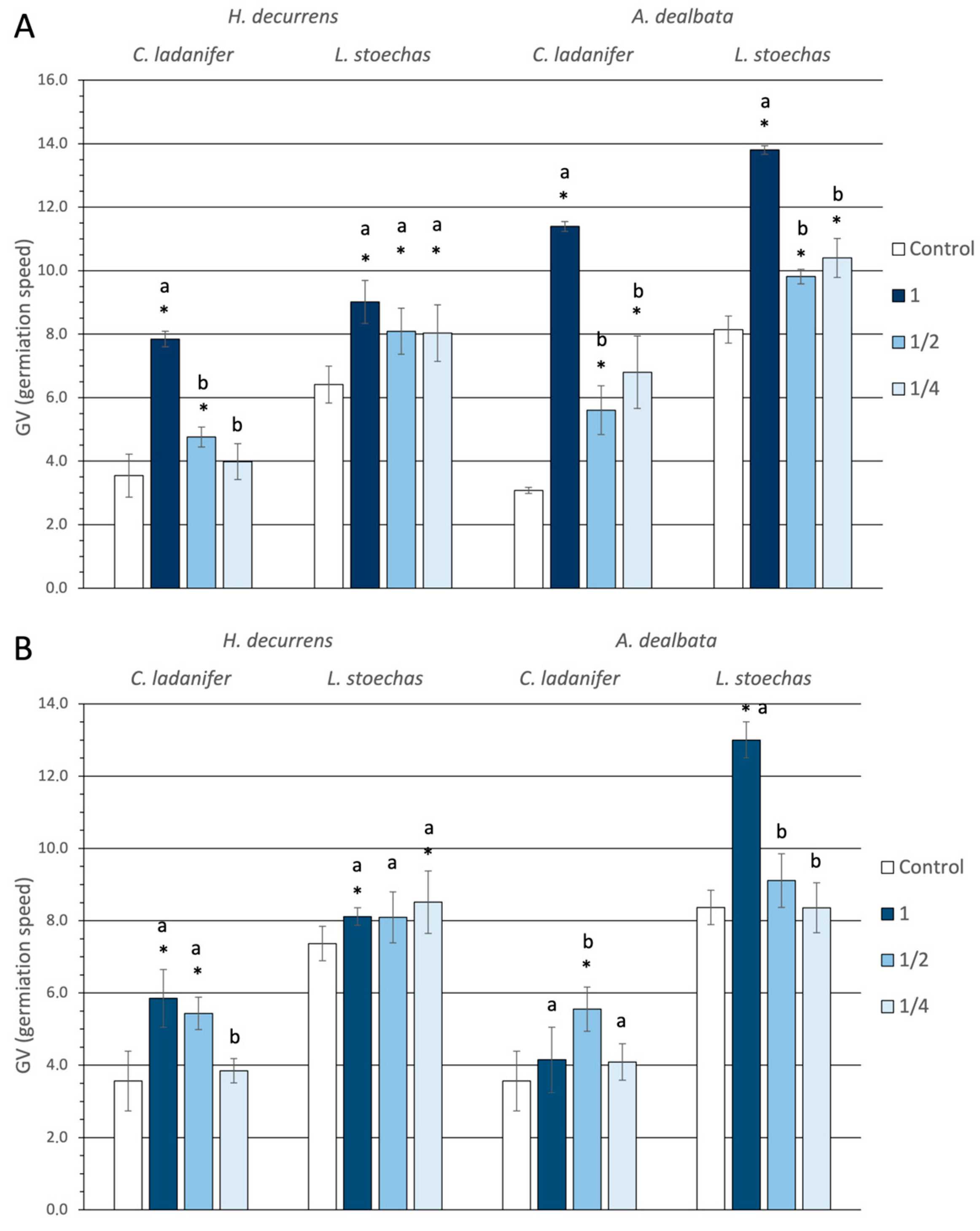

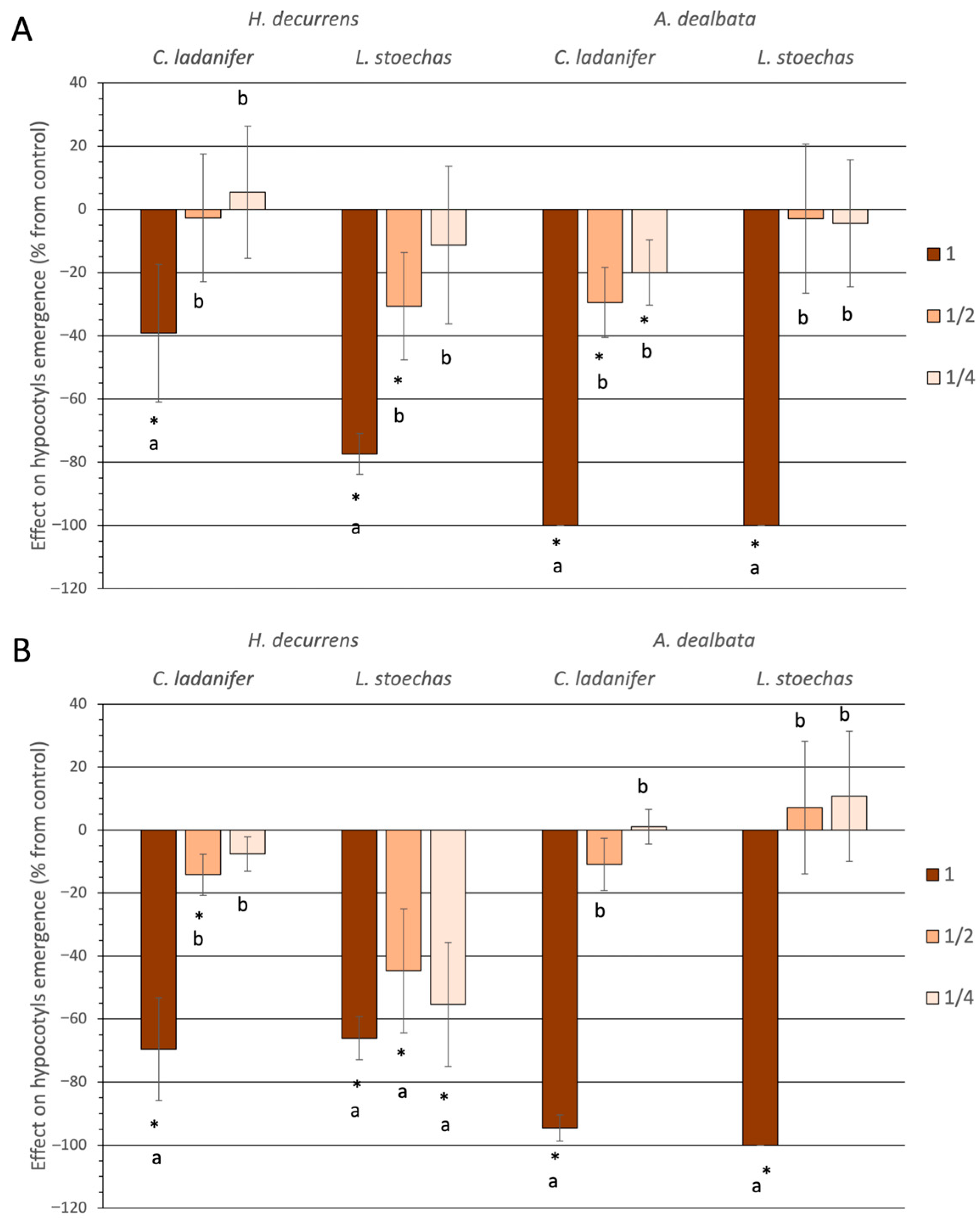

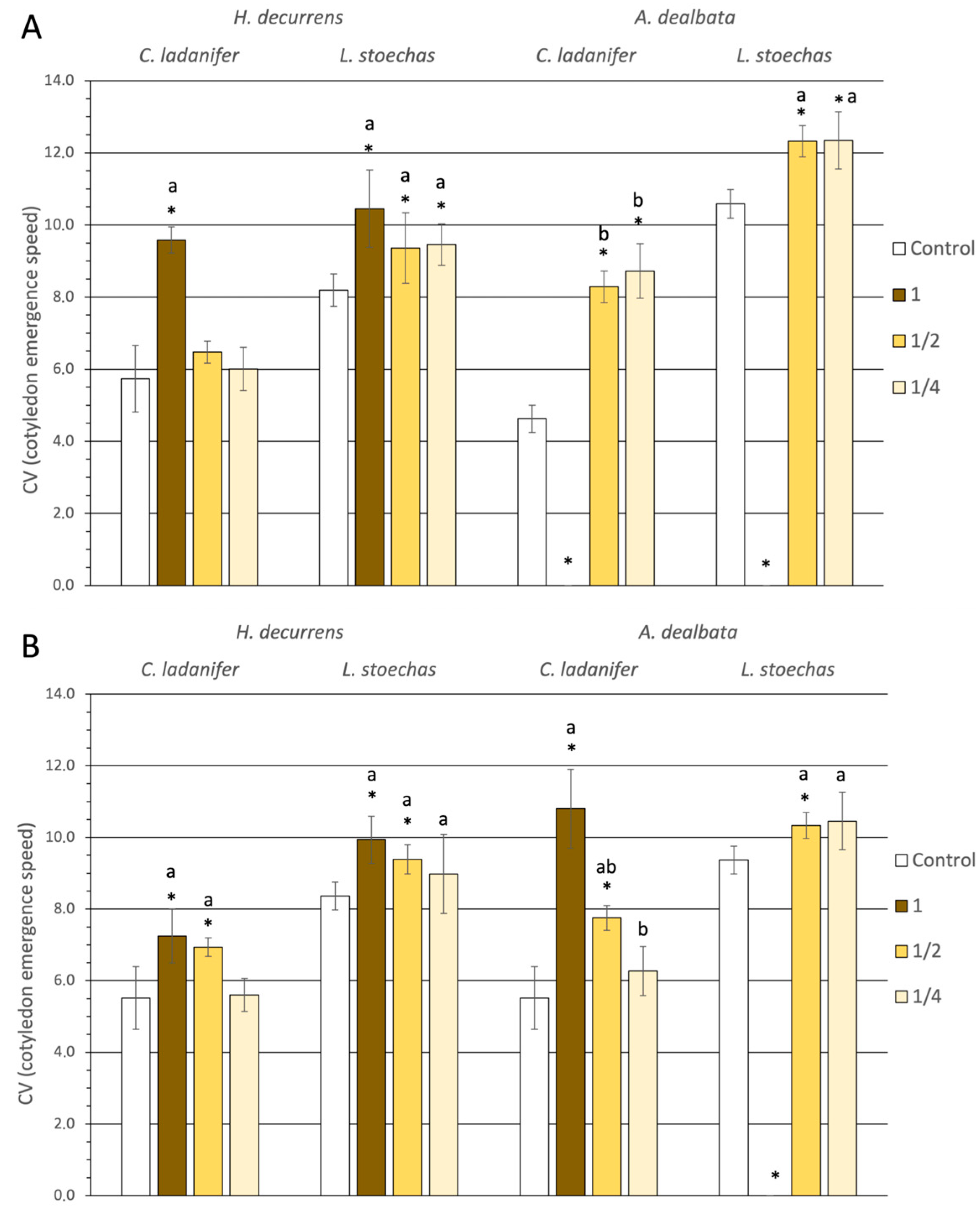

2.1.1. Effect on Germination and Hypocotyl Emergence

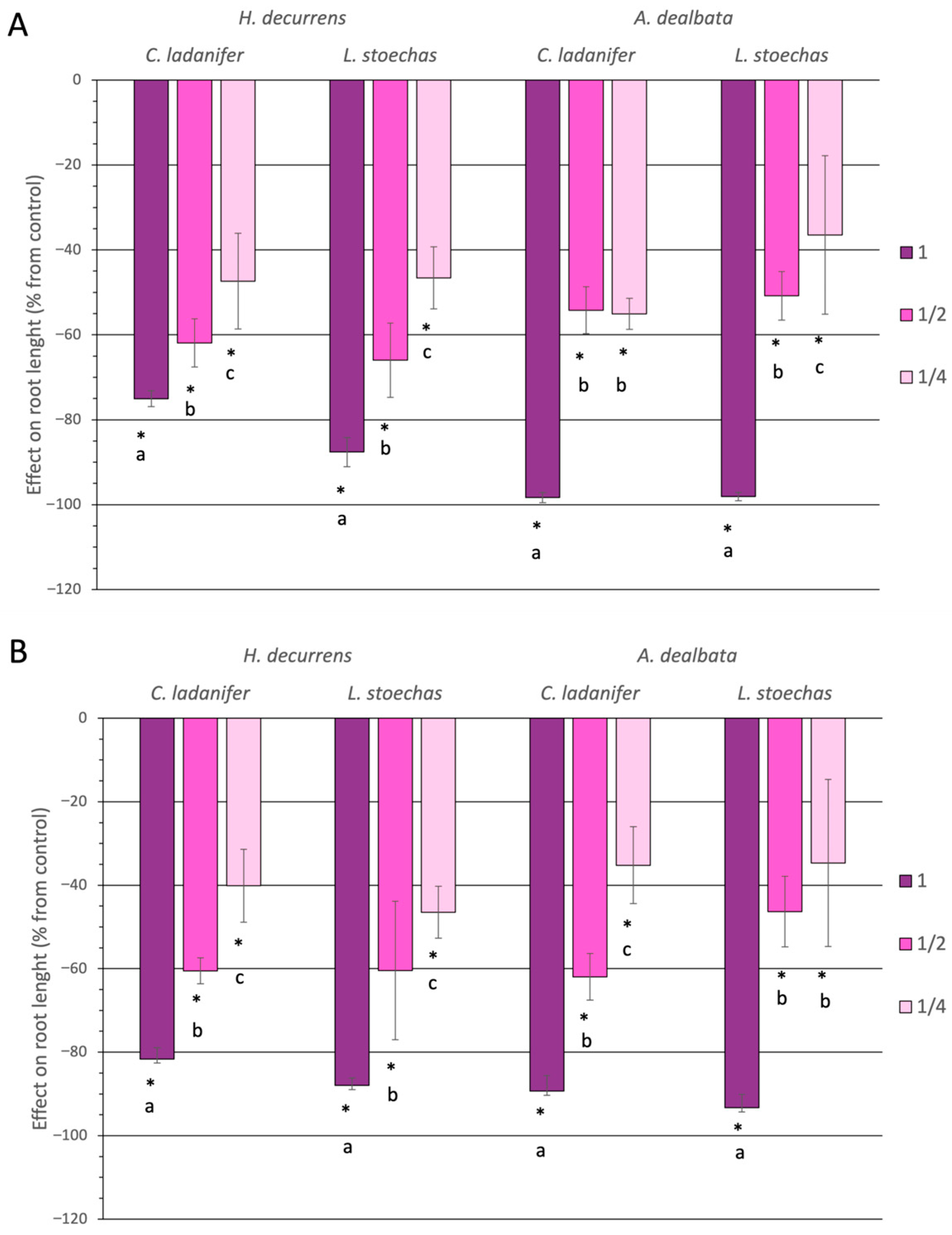

2.1.2. Effect on Root Development

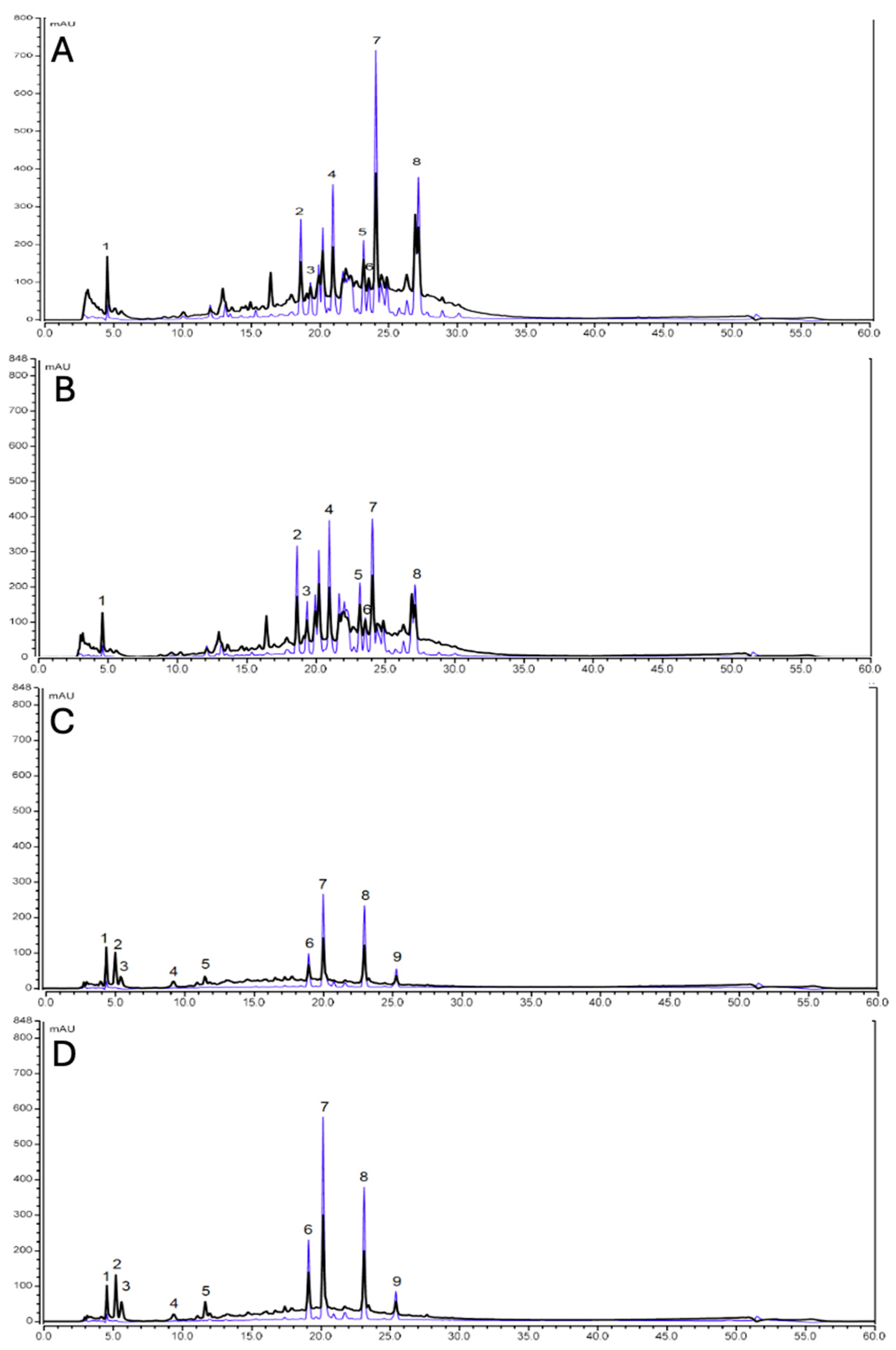

2.2. Phytochemical Analysis of Aqueous Extracts

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of Plant Material and Sample Preparation

4.2. Preparation of Aqueous Extracts

4.3. Biological Assays

- Germination percentage relative to control (%G): Number of seeds germinated in a given treatment relative to the average number of seeds germinated in the control group:

- Hypocotyl emergence percentage relative to control (%C): Calculated using the same formula as germination, replacing germinated seeds with emerged hypocotyls.

- Germination velocity (GV): Arithmetic mean indicating the number of days required for germination, calculated as:

- Hypocotyl emergence velocity (CV): Calculated using the same formula as GV, replacing germination with hypocotyl emergence.

- Root length relative to control (%LR): Average root length expressed as a percentage of the control, calculated as:

4.4. Identification and Quantification of Phenolic Compounds

4.4.1. Identification: UHPLC/Q-TOF MS Method

4.4.2. Quantification: HPLC-DAD Method

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, M.A. Biotic globalization: Does competition from introduced species threaten biodiversity? Bioscience 2003, 53, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, M.; Den Bree, A.; Hui, C.; Richardson, D.M. Impacts of alien plant invasions on species richness in Mediterranean-type ecosystems: A meta-analysis. Prog. Phys. Geog. 2009, 33, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, H.P.; Vepachedu, R.; Gilroy, S.; Callaway, R.M.; Vivanco, J.M. Allelopathy and exotic plant invasion: From molecules and genes to species interactions. Science 2003, 301, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, B.A.; Laginhas, B.B.; Whitlock, R.; Allen, J.M.; Bates, A.E.; Bernatchez, G.; Diez, J.M.; Early, R.; Lenoir, J.; Vilà, M.; et al. Disentangling the abundance–impact relationship for invasive species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9919–9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, P.; Hussain, M.I.; Gonzalez, L. Role of Allelopathy During Invasion Process by Alien Invasive Plants in Terrestrial Ecosystems. In Allelopathy: Current Trends and Future Applications; Cheema, Z.A., Farooq, M., Wahid, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.L. Allelopathy; Academic Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.H.; Yu, J.Q. Allelochemicals and photosynthesis. In Allelopathy: A Physiological Process with Ecological Implications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Weber, E.; van Kleunen, M. Effect of allelopathy on plant performance: A meta-analysis. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkkonen, A. Ecological relationships and allelopathy. In Allelopathy: A Physiological Process with Ecological Implications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, R.M.; Ridenour, W.M. Novel weapons: Invasive success and the evolution of increased competitive ability. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisz, S.; Kivlin, S.N.; Bialic-Murphy, L. Allelopathy is pervasive in invasive plants. Biol. Invasions 2021, 23, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, B.M.; Attiwill, P.M. Nitrogen-fixation by Acacia dealbata and changes in soil properties 5 years after mechanical disturbance or logging following timber harvest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 181, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballeira, A.; Reigosa, M.J. Effects of natural leachates of Acacia dealbata Link in Galicia (NW Spain). Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 1999, 40, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, P.; Gonzalez, L.; Reigosa, M.J. The genus Acacia as invader: The characteristic case of Acacia dealbata Link in Europe. Ann. For. Sci. 2010, 67, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, P.; Pazos-Malvido, E.; Gonzalez, L.; Reigosa, M.J. Allelopathic interference of invasive Acacia dealbata: Physiological effects. Allelop. J. 2008, 22, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, N.; Becerra, J.; Villaseñor-Parada, C.; Lorenzo, P.; González, L.; Hernández, V. Effects and identification of chemical compounds released from the invasive Acacia dealbata Link. Chem. Ecol. 2015, 31, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigosa, M.J. Estudio del potencial alelopático de Acacia dealbata Link. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Santiago, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, N.; González, M.; Alías, J.C. Comparison of the allelopathic potential of non-native and native species of mediterranean ecosystems. Plants 2023, 12, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seigler, D.S. Phytochemistry of Acacia-sensu lato. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2003, 31, 845–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.M.; Barker, W.R.; Haegi, L. Hakea. In Flora de Victoria Volume 3, Dicotyledons Winteraceae a Myrtaceae; Walsh, N.G., Entwisle, T.J., Eds.; Inkata Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1996; pp. 870–882. [Google Scholar]

- Van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H.; Beyer, J.; Champion, P.; Coetzee, J.; Diadema, K.; Kritzinger-Klopper, S.; Marchante, E.; Piet, L.; Richardson, D.M.; Schönberger, I. Naturalised Hakea. What species are we actually talking about in Europe? Bot. Lett. 2024, 171, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T.K.B.; Gerber, D.; Azevedo, J.C. Invasiveness, monitoring and control of Hakea sericea: A systematic review. Plants 2023, 12, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, L.; Alías, J.C.; Blanco-Salas, J.; Montero-Fernández, I.; Chaves, N. Allelopathy and Identification of Allelochemicals in the Leaves of Hakea decurrens subsp. physocarpa WR Barker. Plants 2025, 14, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, D.; Azevedo, J.C.; Nereu, M.; de Oliveira, A.S.; Marchante, E.; Jacobson, T.K.B.; Silva, J.S. Hakea decurrens invasion increases fire hazard at the landscape scale. Biol. Invasions 2024, 26, 3779–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, J.A. Vegetación y Flora de Extremadura. Universitas Editorial; University of Extremadura: Badajoz, Spain, 1995; p. 773. [Google Scholar]

- Khatri, K.; Bargali, K.; Bargali, S.S. Allelopathic effects of fresh and dried leaf extracts of Ageratina adenophora on rice varieties. Discov. Plants 2025, 2, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, A.N.; Pratley, J.E.; Haig, T. Can results from a laboratory bioassay be used as an indicator of field performance of rice cultivars with allelopathic potential against Damasonium minus (Starfruit)? Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 59, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, T.; Ren, C.; Dou, P.; Miao, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, D.; Wang, K. Aqueous extracts of three herbs allelopathically inhibit lettuce germination but promote seedling growth at low concentrations. Plants 2022, 11, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chon, S.U.; Nelson, C.J. Allelopathy in Compositae Plants. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Bao, X.; Niu, K. Seed-to-seed potential allelopathic effects between Ligularia virgaurea and native grass species of Tibetan alpine grasslands. Ecol. Res. 2011, 26, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, B.; Jiang, K. Allelopathic effects of Canada goldenrod leaf extracts on the seed germination and seedling growth of lettuce reinforced under salt stress. Ecotoxicology 2019, 28, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, P.; Rodríguez, J.; González, L.; Rodríguez-Echeverría, S. Changes in microhabitat, but not allelopathy, affect plant establishment after Acacia dealbata invasion. J. Plant Ecol. 2017, 10, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, F.; Kato-Noguchi, H. Seasonal variation in allelopathic activity of japanese red pine needles. Environ. Control Biol. 2014, 52, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kato-Noguchi, H. The seasonal variations of allelopathic activity and allelopathic substances in Brachiaria brizantha. Bot. Stud. 2015, 56, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alías, J.C.; Sosa, T.; Valares, C.; Escudero, J.C.; Chaves, N. Seasonal variation of Cistus ladanifer L. diterpenes. Plants 2012, 1, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderjit; Seastedt, T.R.; Callaway, R.M.; Pollock, J.L.; Kaur, J. Allelopathy and plant invasions: Traditional, congeneric, and bio-geographical approaches. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, R.M.; Aschehoug, E.T. Invasive plants versus their new and old neighbors: A mechanism for exotic invasion. Science 2000, 290, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Kaur, S.; Liao, H.; Kaur, L.; Pyšek, P.; Pergl, J.; Cadotte, M.W.; Callaway, R.M. Invasive Prosopis associated with large, but idiosyncratic, ecosystem changes and loss of native biodiversity across India. Plant Ecol. 2025, 226, 1315–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, M.; Duan, Z.; Shi, H. Comprehensive evaluation of the allelopathic potential of Elymus nutans. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 12389–12400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato-Noguchi, H.; Kobayashi, A.; Ohno, O.; Kimura, F.; Fujii, Y.; Suenaga, K. Phytotoxic substances with allelopathic activity may be central to the strong invasive potential of Brachiaria brizantha. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladhari, A.; Romanucci, V.; De Marco, A.; Di Fabio, G.; Zarrelli, A. Phytotoxic effects of Mediterranean plant extracts on lettuce, tomato and onion as possible additive in irrigation drips. Allelopathy J. 2018, 44, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssali, F.; Moe, S.R.; Sheil, D. The differential effects of bracken (Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn) on germination and seedling performance of tree species in the African tropics. Plant Ecol. 2019, 220, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, J.; Sarada, S. Role of phenolics in allelopathic interactions. Allelopathy J. 2012, 29, 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Marinas, I.; Dinu, M.; Ancuceanu, R.; Marilena, H.; Oprea, E.; Geana, I.; Lazǎr, V. The phenols content and phytotoxic capacity of various invasive plants. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2019, 23, 13887–13899. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.I.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Reigosa, M.J. Allelopathic potential of aqueous extract from Acacia melanoxylon R. Br. on Lactuca sativa. Plants 2020, 9, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumsri, R.; Iwasaki, A.; Suenaga, K.; Kato-Noguchi, H. Assessment of allelopathic potential of Dalbergia cochinchinensis Pierre and its growth inhibitory substance. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2020, 32, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, A.; Gaaliche, B.; Zarrelli, A.; Ghannem, M.; Ben Mimoun, M. Allelopathic potential and phenolic allelochemicals discrepancies in Ficus carica L. cultivars. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 130, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, S.; Carfora, A.; Fiorentino, A.; Natale, A.; Messere, A.; Miglietta, F.; Cotrufo, M.F. Inhibition of net nitrification activity in a Mediterranean woodland: Possible role of chemicals produced by Arbutus unedo. Plant Soil 2009, 315, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, R.; Pal, R.W.; Balazs, V.L.; Mayer, M.; Nagy, D.U.; Cook, B.J.; Farkas, Á. Can seasonal dynamics of allelochemicals play a role in plant invasions? A case study with Helianthus tuberosus L. Plant Ecol. 2016, 217, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, C.M.; Torres, L.M.B.; Torres, M.A.M.G.; Shirasuna, R.T.; Farias, D.A.; dos Santos, N.A., Jr.; Grombone-Guaratini, M.T. Phytotoxic effects of phenolic acids from Merostachys riedeliana, a native and overabundant Brazilian bamboo. Chemoecology 2016, 26, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, A.I.; Pueyo, Y.; Saiz, H.; Alados, C.L. Plant-plant interactions as a mechanism structuring plant diversity in a Mediterranean semi-arid ecosystem. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 5305–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, G.B.; Richardson, D.R.; Fischer, N.H. Allelopathic mechanism in fire-prone communities. In Allelopathy; Rizvi, S.J.H., Rizvi, V., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigulis, K.; Sheppard, A.W.; Ash, J.E.; Groves, R.H. The comparative demography of the pasture weed Echium plantagineum between its native and invaded ranges. J. Appl. Ecol. 2001, 38, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato-Noguchi, H. Isolation and identification of allelochemicals and their activities and functions. J. Pestic. Sci. 2024, 49, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.P.; Raghubanshi, A.S.; Singh, J.S. Lantana invasion: An overview. Weed. Biol. Manag. 2005, 5, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.N.; Hay, A.G.; Weston, L.A. Isolation and characterization of allelopathic volatiles from mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris). J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet-Mélou, A.; Louis, S.; Robles, C.; Greff, S.; Dupouyet, S.; Fernández, C. Allelopathic potential of Medicago arborea, a Mediterranean invasive shrub. Chemoecology 2005, 15, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipollini, K.; Greenawalt, M. Comparison of allelopathic effects of five invasive species on two native species. J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 2016, 143, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Asaeda, T.; Shampa, S.H.; Robinson, R.W. Allelopathy and its coevolutionary implications between native and non-native neighbors of invasive Cynara cardunculus L. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 7463–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkington, R.; Mehrhoff, L.A. The role of competition in structuring pasture communities. In Perspectives on Plant Competition; Grace, J.B., Tilman, D., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 308–366. [Google Scholar]

- Plan Forestal de Extremadura. Análisis y Estudio del Paisaje Vegetal y su Dinámica en la Región de Extremadura. Available online: http://extremambiente.juntaex.es/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3609&Itemid=307 (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Mikulic-Petkovsek, M.; Ravnjak, E.; Rusjan, D. Identification of phenolic compounds in the invasive plants staghorn sumac and himalayan balsam: Impact of time and solvent on the extraction of phenolics and extract evaluation on germination inhibition. Plants 2024, 13, 3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janusauskaite, D. The allelopathic activity of aqueous extracts of Helianthus annuus L., grown in boreal conditions, on germination, development, and physiological indices of Pisum sativum L. Plants 2023, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranal, M.; Santana, D. How and why to measure the germination process? Braz. J. Bot. 2006, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenton, A.G.; Godfrey, A.R. Accurate mass measurement: Terminology and treatment of data. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 21, 1821–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Compounds (mg/g DW) | March | September |

|---|---|---|

| H. decurrens | 3.54 | 5.99 |

| A. dealbata | 12.70 | 12.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nogales, L.; Chaves, N.; Blanco-Salas, J.; Mateos, L.; Rubio, L.V.; Alías, J.C. Allelopathic Effect of the Invasive Species Acacia dealbata Link and Hakea decurrens R.Br., subsp. physocarpa on Native Mediterranean Scrub Species. Plants 2025, 14, 3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233685

Nogales L, Chaves N, Blanco-Salas J, Mateos L, Rubio LV, Alías JC. Allelopathic Effect of the Invasive Species Acacia dealbata Link and Hakea decurrens R.Br., subsp. physocarpa on Native Mediterranean Scrub Species. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233685

Chicago/Turabian StyleNogales, Laura, Natividad Chaves, José Blanco-Salas, Laura Mateos, Luz Victoria Rubio, and Juan Carlos Alías. 2025. "Allelopathic Effect of the Invasive Species Acacia dealbata Link and Hakea decurrens R.Br., subsp. physocarpa on Native Mediterranean Scrub Species" Plants 14, no. 23: 3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233685

APA StyleNogales, L., Chaves, N., Blanco-Salas, J., Mateos, L., Rubio, L. V., & Alías, J. C. (2025). Allelopathic Effect of the Invasive Species Acacia dealbata Link and Hakea decurrens R.Br., subsp. physocarpa on Native Mediterranean Scrub Species. Plants, 14(23), 3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233685