Regulatory Effects of Paclobutrazol and Uniconazole Mixture on the Morphology and Biomass Allocation of Amorpha fruticosa Seedlings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

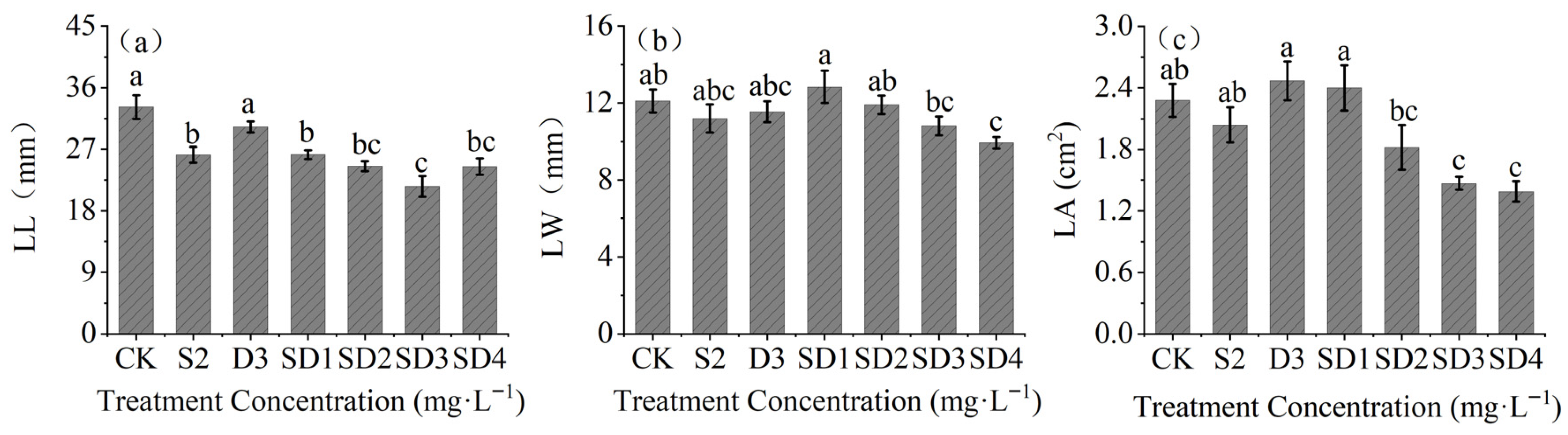

2.1. Effects of Plant Growth Retardants on Seedling Height and Basal Stem Diameter

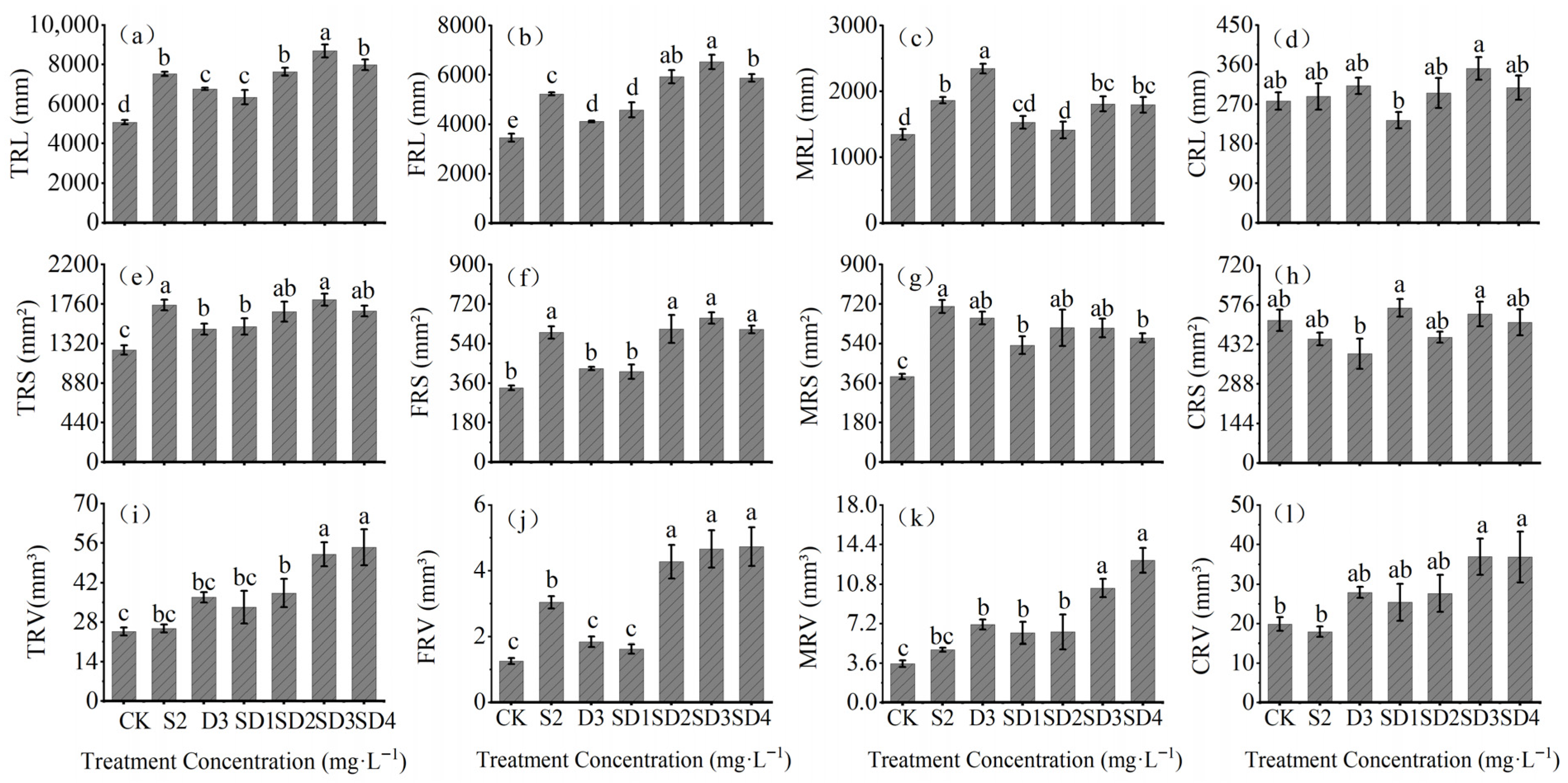

2.2. Effects of Plant Growth Retardants on Root System Development

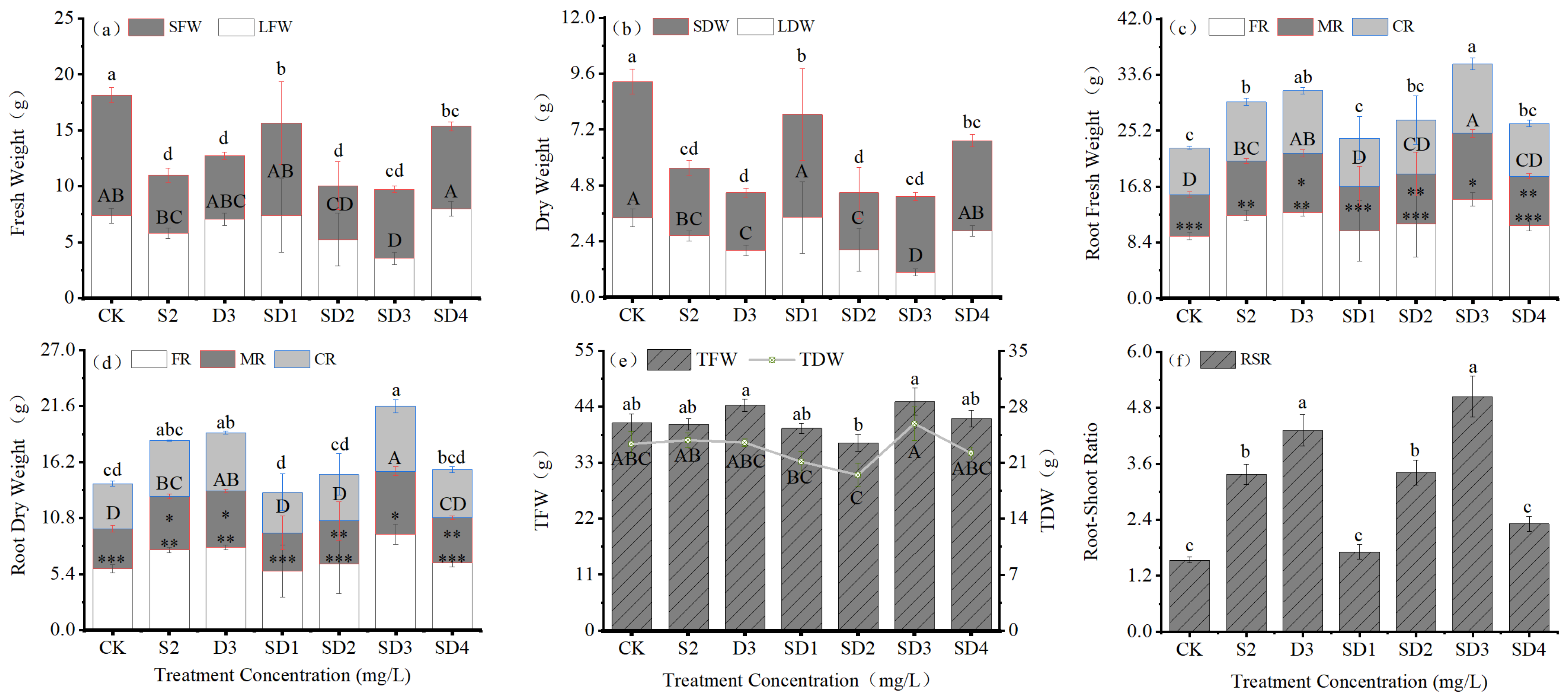

2.3. Effects of Plant Growth Retardants on Biomass Allocation of Seedlings

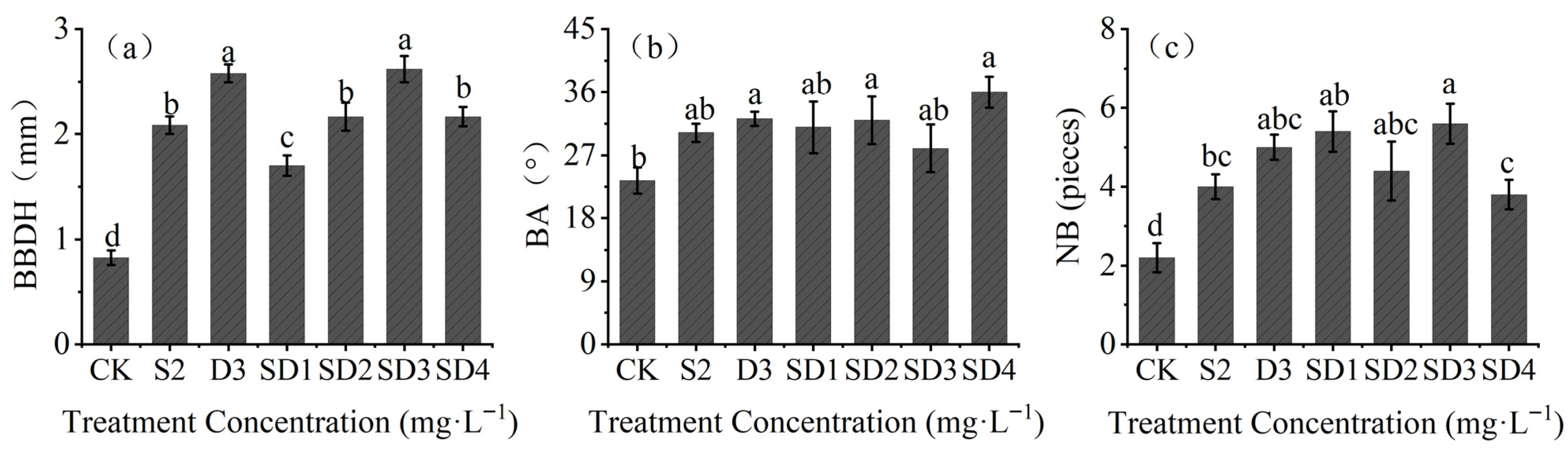

2.4. Effects of Plant Growth Retardants on Branch Growth

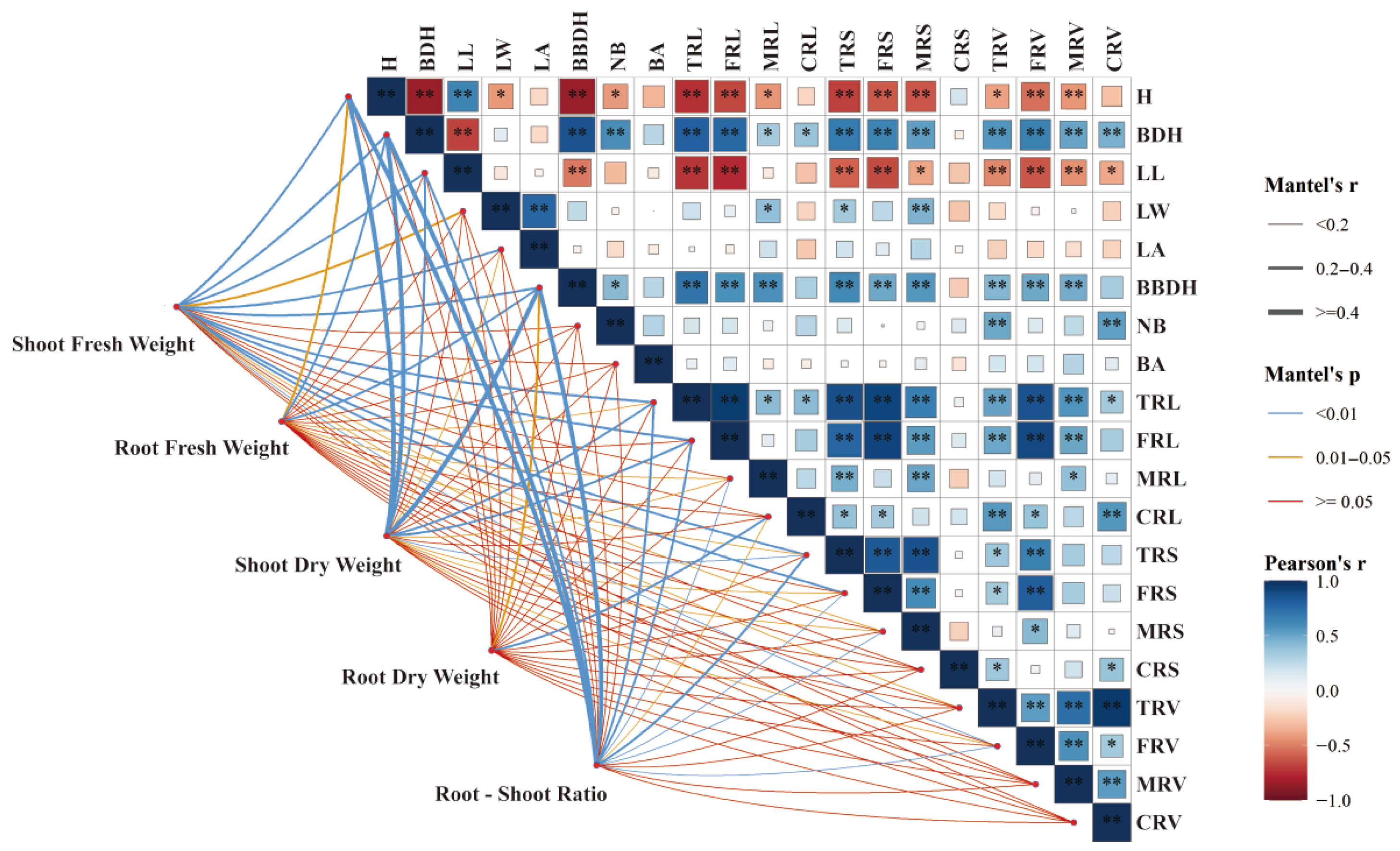

2.5. Correlation Analysis of Morphological Traits Under Different Treatments

2.6. Principal Component Analysis and Comprehensive Evaluation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Measurement of Growth Parameters

4.3.1. Plant Height and Basal Diameter

4.3.2. Branch and Leaf Traits

4.3.3. Root Trait Measurement

4.3.4. Biomass Measurement

4.4. Data Processing and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Ge, Q.; Geng, X.; Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Bryan, B.A.; Chen, S.; Su, Y.; Cai, D.; Ye, J.; et al. Unintended consequences of combating desertification in China. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestre, F.T.; Guirado, E.; Armenteras, D.; Beck, H.E.; AlShalan, M.S.; Al-Saud, N.T.; Chami, R.; Fu, B.; Gichenje, H.; Huber-Sannwald, E.; et al. Bending the curve of land degradation to achieve global environmental goals. Nature 2025, 644, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D. Desertification in northern China from 2000 to 2020: The spatial-temporal processes and driving mechanisms. Eco. Inform. 2024, 82, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yang, B.; Wu, G.; Feng, G.; Ljungqvist, F.C.; Che, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Guan, X.; Huang, C.; et al. Increased desertification exposure in dryland areas. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 179, 114264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Lu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Lu, M.; Qin, Y.; Sun, D.; Ding, Z. Research on desertification monitoring and vegetation refinement extraction methods based on the synergy of multisource remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4404819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perović, V.; Kadović, R.; Đurđević, V.; Pavlović, D.; Pavlović, M.; Cakmak, D.; Mitrović, M.; Pavlović, P. Major drivers of land degradation risk in Western Serbia: Current trends and future scenarios. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 123, 107377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnashar, A.; Zeng, H.; Wu, B.; Gebremicael, T.G.; Marie, K. Assessment of environmentally sensitive areas to desertification in the Blue Nile Basin driven by the MEDALUS-GEE framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Li, M.; Sun, T. The status and trend analysis of desertification and sandification. For. Resour. Manag. 2016, 1, 1–5+13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Jia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Peng, B.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, M. Spatiotemporal characteristics and driving mechanism of land degradation sensitivity in Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, D. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors analysis of fractional vegetation coverage in the arid region of northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shen, Y.; Wang, G.; Ma, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, G.; Huo, X.; Liu, Z. Plant species diversity and functional diversity relations in the degradation process of desert steppe in an arid area of northwest China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, C.; Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Ren, Z.; Stringer, L.C. Changes and drivers of vegetation productivity in China’s drylands under climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 114001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, L.; Niu, Z.; Nath, B. Vegetation recovery and recent degradation in different karst landforms of Southwest China over the past two decades using GEE Satellite archives. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 68, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, K.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, X.; Wang, G.G.; Li, M. Impacts of the world’s largest afforestation program (Three-North Afforestation Program) on desertification control in sandy land of China. GISci. Remote Sens. 2023, 60, 2167574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Huang, J. Constructing semi-arid ecological barriers to prevent desertification. Innov. Geosci. 2024, 2, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, S.A.; Nickling, W.G. The protective role of sparse vegetation in wind erosion. Prog. Phys. Geog. 1993, 17, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryrear, D.W.; Bilbro, J.D.; Saleh, A.R.W.E.Q.; Schomberg, H.; Stout, J.E.; Zobeck, T.M. RWEQ: Improved wind erosion technology. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2000, 55, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Koyama, A.; Okuro, T. Coupling structural and functional thresholds for vegetation changes on a Mongolian shrubland. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, H.; Young, J.; Napelenok, S.; Ran, L.; Appel, K.W.; Gilliam, R.C.; Pleim, J. Development and evaluation of a physics-based windblown dust emission scheme implemented in the CMAQ modeling system. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2017, 9, 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. The Study on Architecture and Wind Break Efficiency of Imitation Sand–Fixed Shrub. Ph.D. Thesis, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, China, 2012. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.L.; Cheng, H.; Xie, Q.M.; Hou, H.; Ni, X.L. Evaluation of drought resistance of six shrubs in arid area and selection of identification indexes. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2022, 37, 24–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wilder, B.T.; Hultine, K.R.; Dorshow, W.B.; Vanderplank, S.E.; López, B.R.; Medel-Narváez, A.; Marvan, M.; Kindl, K.; Musgrave, A.; Macfarlan, S.; et al. Plant responses to anomalous heat and drought events in the Sonoran desert. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cui, G.; Li, G.; Lu, H.; Wei, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H. Assessing the efficacy and residual impact of plant growth retardants on crop lodging and overgrowth: A review. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 159, 127276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaw, T.; Hammes, S.; Robbertse, J. Paclobutrazol induced leaf, stem, and root anatomical modifications in potato. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2005, 40, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Gai, D.; Liang, J.; Cui, J.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, L.; Shao, X. Paclobutrazol enhances lodging resistance and yield of direct-seeded rice by optimizing plant type and canopy light transmittance. Field Crop. Res. 2025, 331, 109882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Deng, Y.; Ou, Y.; Ma, D.; Li, D.; Xie, W.; Li, Z. Effects of PBO and PP333 on shoot growth, nutrient accumulation, and fruit quality in Carya Illinoinensis cv. ‘Shaoxing’. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 93, 3293–3312. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, X.; Chu, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Song, R.; Fang, Y.; et al. Effects of exogenous paclobutrazol and sampling time on the efficiency of in vitro embryo rescue in the breeding of new seedless grape varieties. J. Int. Agric. 2022, 21, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ajlouni, M.G.; Othman, Y.A.; A’saf, T.S.; Ayad, J.Y. Lilium morphology, physiology, anatomy and postharvest flower quality in response to plant growth regulators. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 156, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, W. Growth retardants: Effects on gibberellin biosynthesis and other metabolic pathways. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2000, 51, 501–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, N.; Sun, T.; Gubler, F. Gibberellin signaling: Biosynthesis, catabolism and response pathways. Plant Cell. 2002, 14, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, L. Plant Growth and Development: Hormones and Environment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 16, pp. 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wittwer, S.; Tolbert, N. 2-chloroethyl trimethylammonium chloride and related compounds as plant growth substances. V. Growth, flowering, and fruiting responses as related to those induced by auxin and gibberellin. Plant Physiol. 1960, 35, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, K.; Kamiya, Y.; Sakurai, A.; Oshio, H.; Takahashi, N. Studies of sites of action of a new plant growth retardant (E)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4,4-dimethyl-2-(1, 2, 4-triazol-1-yl)-1-penten-3-ol (S-3307) and comparative effects of its stereoisomers in a cell-free system from Cucurbita maxima. Plant Cell Physiol. 1985, 26, 821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.; Yuan, T. Effect of GA and PP333 on autumn reflowering of two Chinese tree peony (Paeonia × suffruticosa Andrews) cultivars. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 177, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Okamoto, M.; Shinoda, S.; Kushiro, T.; Koshiba, T.; Kamiya, Y.; Hirai, N.; Todoroki, Y.; Sakata, K.; Nambara, E.; et al. A plant growth retardant, Uniconazole, is a potent inhibitor of ABA catabolism in Arabidopsis. Biosci. Biotech. Bioch. 2006, 70, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Feng, N.; Zheng, D.; Cui, H.; Sun, F.; Gong, X. Uniconazole and diethyl aminoethyl hexanoate increase soybean pod setting and yield by regulating sucrose and starch content. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Feng, N.; Zheng, D.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Huo, J.; Mei, W. Effects of exogenous Uniconazole (S3307) on oxidative damage and carbon metabolism of rice under salt stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wang, N.; Ren, W.; Zhang, R.; Hong, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, K.; Shu, Y.; Hu, N.; Yang, Y. Molecular dissection unveiling dwarfing effects of plant growth retardants on pomegranate. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 866193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Fan, G. Maize straw mulching with uniconazole application increases the tillering capacity and grain yield of dryland winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Field Crop. Res. 2022, 284, 108573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Lin, C.; Jiang, Z.; Yan, F.; Li, Z.; Tang, X.; Yang, F.; Ding, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; et al. Uniconazole enhances lodging resistance by increasing structural carbohydrate and sclerenchyma cell wall thickness of japonica rice (Oryza sativa L.) under shading stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 206, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Mao, G. Effects of different carrier bacterial fertilizers on growth, photosynthetic characteristics and soil nutrients of Amorpha fruticosa. J. Nanjing For. Univ. 2024, 48, 81–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bi, Y.; Du, X.; Tian, L.; Li, M.; Yin, K. Effects of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus on Amorpha fruticosa roots and soil preferential flow in an arid area of opencast coal mine waste. Soil Till. Res. 2025, 245, 106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Li, S.; Sun, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y. Effects of soil-applied paclobutrazol on growth and physiological characteristics of Amorpha fruticosa. Plant Physiol. J. 2015, 51, 1495–1501. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Hu, W.; Sun, Y.; Morriën, E.; Yang, Q.; Aqeel, M.; Du, Q.; Xiong, J.; Dong, L.; Yao, S.; et al. Active restoration efforts drive community succession and assembly in a desert during the past 53 years. Ecol. Appl. 2025, 35, e3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurans, M.; Munoz, F.; Charles-Dominique, T.; Heuret, P.; Fortunel, C.; Isnard, S.; Sabatier, A.A.; Caraglio, Y.; Violle, C. Why incorporate plant architecture into trait-based ecology? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2024, 39, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fu, B.; Deng, R.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, J.; Tang, J. Integrating remote sensing and mechanistic model for spatial evaluation of shelterbelt porosity and windbreak effectiveness in agricultural landscapes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 374, 110822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Jiang, Y.; Han, W.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Cui, Y.; Du, X.; Gao, Z.; Liang, X. Simultaneous enhancement of maize yield and lodging resistance via delaying plant growth retardant application. Field Crop. Res. 2024, 317, 109530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthélémy, D.; Caraglio, Y. Plant architecture: A dynamic, multilevel and comprehensive approach to plant form, structure and ontogeny. Ann. Bot. 2007, 99, 375–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Akhtar, G.; Shehzad, M.; Ullah, S.; Faried, H.; Razzaq, K.; Nawaz, F.; Rajwana, I.; Amin, M.; Ahsan, M. Paclobutrazol and maleic hydrazide-induced growth inhibition in warm season turfgrasses through structural and physiological differences. Kuwait J. Sci. 2023, 50, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Ruan, Y.; Liu, C. Pod canopy staggered-layer cultivation increases rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) yield by improving population canopy structure and fully utilizing light-energy resources. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 158, 127229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebmeyer, H.; Fiedler-Wiechers, K.; Hoffmann, C. Drought tolerance of sugar beet-Evaluation of genotypic differences in yield potential and yield stability under varying environmental conditions. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 125, 126262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testerink, C.; Lamers, J. How plant roots go with the flow. Nature 2022, 612, 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Xia, M.; Wei, X.; Chang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. Anatomical traits associated with absorption and mycorrhizal colonization are linked to root branch order in twenty-three Chinese temperate tree species. New Phytol. 2008, 180, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, M.; Dickie, I.; Eissenstat, D.; Fahey, T.; Fernandez, C.; Guo, D.; Helmisaari, H.; Hobbie, E.; Iversen, C.; Jackson, R.; et al. Redefining fine roots improves understanding of below-ground contributions to terrestrial biosphere processes. New Phytol. 2015, 207, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, M.; Brown, S.; Baumgardner, H. Root biomass allocation in the world’s upland forests. Oecologia 1997, 111, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobbagy, E.; Jackson, R. The Vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its relation to climate and vegetation. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, G.; Jobbágy, R. The Distribution of Soil Nutrients with Depth: Global Patterns and the Imprint of Plants. Biogeochemistry 2001, 53, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, B.; Wang, D.; Snyder, M.; Bormann, F.; Benoit, G.; April, R. Raped, plant-induced weathering in an aggrading experimental Ecosystem. Biogeochemistry 1998, 43, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ali, S.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Pang, G.; Assal, M.; Rafi Shaik, M. Irrigation management practices with novel plant growth regulators improve root growth, root lodging resistance and maize productivity under semi-arid regions. Field Crop. Res. 2025, 333, 110097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Meng, Y.; Wang, N.; Shi, C. Impact of paclobutrazol on storage root number and yield of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.). Field Crop. Res. 2023, 300, 109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, K.; Su, W.; Irshad, A.; Meng, X.; Cui, W.; Zhang, X.; Mou, S.; Aaqil, K.; Han, Q.; Liu, T. Application of paclobutrazol affect maize grain yield by regulating root morphological and physiological characteristics under a semi-arid region. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Liu, Y.; Buitrago, S.; Jiang, W.; Gao, H.; Han, H.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X. Adventitious root formation is dynamically regulated by various hormones in leaf-vegetable sweet potato cuttings. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 253, 153267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Song, Z.; Cong, P.; Cheng, H.; Zheng, X.; Song, W.; Yue, P.; Wang, S.; Zuo, X. Precipitation-induced biomass enhancement and differential allocation in Inner Mongolia’s herbaceous and shrub communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña, M.N.; Cao, M.; Lin, L.; Swenson, N.G.; Zhang, C. Trade-offs in above- and below-ground biomass allocation influencing seedling growth in a tropical forest. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Xu, X.; Liao, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, J. Ampelocalamus luodianensis (Poaceae), a plant endemic to karst, adapts to resource heterogeneity in differing microhabitats by adjusting its biomass allocation. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 41, e02374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, T.; Corina, G.; Jordi, S.; Zeng, F.; Alice, C.H.; Zeeshan, A.; Abd, U.; Sikandar, A.; Gao, Y.; Josep, P. Plant root mechanisms and their effects on carbon and nutrient accumulation in desert ecosystems under changes in land use and climate. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 916–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.W. Effect of transplanting and paclobutrazol on root growth of ‘Green Column’ black maple and ‘Summit’ green ash. J. Environ. Hortic. 2004, 22, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, R.; McCullough, D.G.; Bert, M.C. Effects of paclobutrazol and fertilizer on the physiology, growth and biomass allocation of three Fraxinus species. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Effects of Plant Growth Retardants on the Phenotype Characteristics of Amorpha fruticosa Seedlings. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wu, A. Effects of Combined Administration of Naphthalene Acetic Acid with Paclobutrazol on Growth and Biomass Allocation of Carya illinoensis ‘Pawnee’ Container Seedling. J. Northeast For. Univ. 2023, 51, 64–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. The Effects of Plant Retardant on Phenotypic Plasticity of Hedysarum laeve Under Drought and Saline-Alkali Stress. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Michael, G.; Patrick, J.F.G.; Trevor, H.; Alfonso, I.; Angelos, M.; Elena, T. Principal component analysis. Nat. Rev. Method. Prime. 2022, 2, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew, C. Notes on the use of principal component analysis in agronomic research. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2025, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Guo, B.; Guo, Y.; Ma, X.; Luo, S.; Feng, L.; Pan, Z.; Deng, L.; Pan, S.; Wei, J.; et al. A comprehensive “quality-quantity-activity” approach based on portable near-infrared spectrometer and membership function analysis to systematically evaluate spice quality: Cinnamomum cassia as an example. Food Chem. 2024, 439, 138142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | Treatment Concentration (mg·L–1) | Treatment Time (d) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 75 | 90 | ||

| H (cm) | CK | 22.24 ± 0.49 a | 17.60 ± 1.00 a | 8.62 ± 0.46 a | 1.88 ± 0.14 a | 0.86 ± 0.08 a | 0.20 ± 0.04 ab |

| S2 | 4.36 ± 0.16 cd | 2.86 ± 0.18 bc | 0.52 ± 0.04 d | 0.20 ± 0.03 e | 0.10 ± 0.03 c | 0.08 ± 0.04 b | |

| D3 | 5.20 ± 0.52 c | 3.86 ± 0.31 bc | 2.40 ± 0.20 b | 1.44 ± 0.25 b | 0.84 ± 0.17 a | 0.20 ± 0.06 ab | |

| SD1 | 7.74 ± 0.44 b | 4.10 ± 0.26 b | 2.28 ± 0.27 b | 1.04 ± 0.16 c | 0.50 ± 0.05 b | 0.14 ± 0.05 ab | |

| SD2 | 7.11 ± 0.51 b | 3.24 ± 0.32 bc | 1.52 ± 0.14 c | 0.72 ± 0.12 cd | 0.30 ± 0.05 bc | 0.14 ± 0.04 ab | |

| SD3 | 3.76 ± 0.25 d | 1.44 ± 0.09 d | 1.02 ± 0.04 cd | 0.54 ± 0.05 de | 0.40 ± 0.07 b | 0.28 ± 0.06 a | |

| SD4 | 5.62 ± 0.62 c | 2.56 ± 0.40 cd | 1.34 ± 0.22 c | 0.72 ± 0.07 cd | 0.28 ± 0.04 bc | 0.26 ± 0.05 a | |

| BDH (mm) | CK | 0.28 ± 0.02 d | 0.19 ± 0.02 d | 0.13 ± 0.02 c | 0.09 ± 0.009 c | 0.05 ± 0.007 b | 0.02 ± 0.006 a |

| S2 | 0.89 ± 0.05 c | 0.74 ± 0.04 ab | 0.44 ± 0.05 ab | 0.17 ± 0.03 ab | 0.07 ± 0.03 ab | 0.02 ± 0.006 a | |

| D3 | 0.93 ± 0.06 c | 0.74 ± 0.05 ab | 0.51 ± 0.05 a | 0.19 ± 0.03 ab | 0.08 ± 0.005 ab | 0.04 ± 0.02 a | |

| SD1 | 0.92 ± 0.05 c | 0.58 ± 0.05 c | 0.36 ± 0.03 b | 0.14 ± 0.01 bc | 0.11 ± 0.03 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | |

| SD2 | 1.31 ± 0.05 b | 0.64 ± 0.06 bc | 0.43 ± 0.05 ab | 0.19 ± 0.02 ab | 0.11 ± 0.02 a | 0.02 ± 0.009 a | |

| SD3 | 1.78 ± 0.06 a | 0.80 ± 0.04 a | 0.52 ± 0.05 a | 0.23 ± 0.03 a | 0.09 ± 0.009 ab | 0.01 ± 0.007 a | |

| SD4 | 0.93 ± 0.03 c | 0.73 ± 0.02 ab | 0.42 ± 0.05 ab | 0.23 ± 0.01 a | 0.11 ± 0.01 a | 0.03 ± 0.007 a | |

| Traits | Root System Classification | CK | S2 | D3 | SD1 | SD2 | SD3 | SD4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFW | FR | 41.25 ± 0.58 a | 42.11 ± 0.55 a | 41.35 ± 0.60 a | 42.05 ± 0.55 a | 41.84 ± 0.49 a | 42.17 ± 0.58 a | 41.49 ± 0.60 a |

| MR | 27.66 ± 0.68 a | 27.89 ± 0.55 a | 28.43 ± 0.68 a | 27.97 ± 0.54 a | 27.80 ± 0.58 a | 28.13 ± 0.49 a | 28.29 ± 0.67 a | |

| CR | 31.09 ± 0.80 a | 30.00 ± 0.44 ab | 30.22 ± 0.37 ab | 29.97 ± 0.45 ab | 30.36 ± 0.40 ab | 29.70 ± 0.40 ab | 30.22 ± 0.37 b | |

| RDW | FR | 41.79 ± 1.07 a | 42.21 ± 0.86 a | 41.82 ± 0.80 a | 42.78 ± 0.86 a | 42.40 ± 0.40 a | 42.79 ± 1.03 a | 41.86 ± 0.49 a |

| MR | 27.51 ± 1.02 a | 28.24 ± 0.73 a | 28.57 ± 0.81 a | 27.64 ± 0.97 a | 27.70 ± 0.68 a | 28.15 ± 0.87 a | 28.10 ± 0.86 a | |

| CR | 30.70 ± 0.97 a | 29.56 ± 0.51 a | 29.61 ± 0.24 a | 29.58 ± 0.75 a | 29.91 ± 0.55 a | 29.06 ± 0.45 a | 30.05 ± 0.55 a | |

| RS | FR | 27.24 ± 0.92 b | 37.50 ± 1.14 a | 25.39 ± 0.54 b | 27.30 ± 1.15 b | 36.11 ± 3.34 a | 36.29 ± 0.76 a | 36.02 ± 1.14 a |

| MR | 31.32 ± 0.58 c | 39.91 ± 0.95 a | 39.03 ± 1.43 ab | 35.16 ± 1.20 abc | 36.16 ± 3.58 abc | 33.76 ± 2.10 bc | 33.77 ± 1.55 bc | |

| CR | 41.44 ± 1.48 a | 22.60 ± 1.26 c | 23.82 ± 3.45 bc | 37.54 ± 1.03 a | 27.73 ± 1.95 bc | 29.96 ± 2.18 b | 30.21 ± 2.09 b | |

| RV | FR | 5.24 ± 0.65 c | 13.78 ± 0.94 a | 5.02 ± 0.42 c | 5.25 ± 0.59 c | 11.73 ± 1.85 ab | 9.21 ± 1.38 b | 9.14 ± 1.33 b |

| MR | 14.75 ± 1.99 c | 22.47 ± 0.83 ab | 19.28 ± 0.71 abc | 19.27 ± 0.62 abc | 17.13 ± 3.70 bc | 20.58 ± 2.17 abc | 24.67 ± 2.90 a | |

| CR | 80.00 ± 2.60 a | 63.74 ± 1.62 c | 75.70 ± 0.94 ab | 75.48 ± 1.08 ab | 71.14 ± 3.28 bc | 70.22 ± 3.09 bc | 66.18 ± 4.11 c |

| Index | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | PC7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | −0.118 | −0.555 | −0.595 | −0.282 | −0.334 | −0.135 | 0.127 |

| BDH | 0.266 | 0.606 | 0.461 | −0.051 | 0.464 | 0.153 | −0.062 |

| LL | −0.091 | −0.668 | −0.359 | −0.028 | −0.193 | −0.068 | −0.392 |

| LW | −0.020 | 0.153 | 0.187 | 0.829 | −0.049 | −0.093 | −0.146 |

| LA | −0.199 | 0.054 | 0.025 | 0.870 | −0.101 | −0.126 | 0.086 |

| BBDH | 0.372 | 0.408 | 0.594 | 0.114 | 0.303 | 0.259 | −0.266 |

| NB | 0.143 | −0.025 | 0.325 | −0.057 | 0.789 | 0.071 | 0.201 |

| BA | −0.343 | 0.070 | 0.097 | −0.082 | 0.557 | 0.152 | −0.348 |

| TRL | 0.228 | 0.894 | 0.263 | 0.048 | 0.042 | 0.238 | −0.008 |

| FRL | 0.070 | 0.937 | 0.200 | −0.092 | 0.081 | 0.116 | 0.120 |

| MRL | 0.461 | 0.082 | 0.293 | 0.415 | −0.110 | 0.455 | −0.389 |

| CRL | 0.534 | 0.350 | −0.203 | −0.156 | 0.404 | 0.162 | −0.017 |

| TRS | 0.255 | 0.815 | 0.198 | 0.303 | 0.074 | 0.090 | −0.062 |

| FRS | 0.147 | 0.935 | 0.125 | 0.079 | −0.064 | 0.018 | 0.011 |

| MRS | 0.164 | 0.641 | 0.220 | 0.407 | 0.036 | −0.080 | −0.324 |

| CRS | 0.031 | 0.061 | −0.212 | −0.051 | 0.080 | 0.163 | 0.820 |

| TRV | 0.179 | 0.336 | 0.055 | −0.160 | 0.470 | 0.671 | 0.294 |

| FRV | 0.027 | 0.862 | 0.126 | −0.251 | 0.042 | 0.260 | 0.008 |

| MRV | 0.056 | 0.352 | 0.173 | −0.116 | 0.115 | 0.806 | 0.043 |

| CRV | 0.206 | 0.186 | −0.004 | −0.129 | 0.556 | 0.557 | 0.361 |

| LFW | −0.247 | −0.346 | −0.483 | 0.499 | 0.036 | 0.323 | −0.058 |

| SFW | −0.047 | −0.457 | −0.766 | −0.238 | −0.101 | −0.064 | 0.109 |

| LDW | −0.279 | −0.351 | −0.573 | 0.457 | −0.250 | 0.028 | 0.284 |

| SDW | −0.061 | −0.321 | −0.794 | −0.219 | −0.129 | −0.111 | 0.142 |

| FRFW | 0.779 | 0.213 | 0.496 | −0.067 | −0.068 | 0.142 | 0.165 |

| MRFW | 0.788 | 0.248 | 0.435 | −0.075 | 0.020 | 0.177 | 0.083 |

| CRFW | 0.804 | 0.177 | 0.475 | −0.068 | −0.054 | 0.134 | 0.160 |

| FRDW | 0.926 | 0.181 | 0.170 | −0.060 | 0.101 | −0.025 | −0.054 |

| MRDW | 0.892 | 0.260 | 0.113 | −0.058 | 0.137 | 0.000 | −0.177 |

| CRDW | 0.929 | 0.154 | 0.140 | −0.046 | 0.100 | −0.054 | −0.093 |

| TFW | 0.858 | −0.136 | −0.027 | 0.018 | −0.078 | 0.286 | 0.215 |

| TDW | 0.917 | −0.013 | −0.327 | −0.023 | 0.000 | −0.067 | 0.028 |

| RSR | 0.624 | 0.243 | 0.645 | −0.175 | 0.158 | 0.038 | −0.148 |

| Eigenvalue | 13.534 | 5.064 | 3.374 | 2.296 | 2.004 | 1.265 | 1.002 |

| Contribution rate (%) | 41.013 | 15.345 | 10.224 | 6.959 | 6.071 | 3.832 | 3.035 |

| Accumulated contribution rate (%) | 41.013 | 56.358 | 66.582 | 73.541 | 79.612 | 83.444 | 86.479 |

| Treatment Concentration | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | PC7 | Comprehensive Score | Rank Order |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD3 | 5.25 | 1.72 | 1.66 | −0.75 | −0.94 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 2.91 | 1 |

| SD4 | 0.43 | 1.74 | 1.54 | 1.23 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.21 | 0.90 | 2 |

| D3 | 1.44 | 1.26 | −1.82 | −1.28 | 1.99 | 0.39 | −0.26 | 0.74 | 3 |

| SD2 | 0.60 | 1.69 | 0.50 | −1.31 | −0.74 | −0.42 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 4 |

| S2 | 1.81 | −1.18 | −2.82 | 1.67 | −1.31 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.36 | 5 |

| SD1 | −3.15 | −0.89 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 1.15 | −0.98 | 0.58 | −1.55 | 6 |

| CK | −6.38 | −2.54 | 0.50 | 0.10 | −1.05 | 0.12 | −0.35 | −3.49 | 7 |

| Treatments | Plant Buffer Concentration | Application Rate (mL) | Number of Plants |

|---|---|---|---|

| CK | Clear water | 200 | 5 |

| S2 | S3307 200 mg·L–1 | 200 | 5 |

| D3 | PP333 300 mg·L–1 | 200 | 5 |

| SD1 | S3307 100 mg·L–1 + PP333 200 mg·L–1 | 200 | 5 |

| SD2 | S3307 100 mg·L–1 + PP333 300 mg·L–1 | 200 | 5 |

| SD3 | S3307 200 mg·L–1 + PP333 200 mg·L–1 | 200 | 5 |

| SD4 | S3307 200 mg·L–1 + PP333 300 mg·L–1 | 200 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Liu, N.; Wu, K.; Zhang, X.; Gao, C.; Liu, F.; Sun, J.; Liu, C. Regulatory Effects of Paclobutrazol and Uniconazole Mixture on the Morphology and Biomass Allocation of Amorpha fruticosa Seedlings. Plants 2025, 14, 3684. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233684

Zhang J, Liu N, Wu K, Zhang X, Gao C, Liu F, Sun J, Liu C. Regulatory Effects of Paclobutrazol and Uniconazole Mixture on the Morphology and Biomass Allocation of Amorpha fruticosa Seedlings. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3684. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233684

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jiapeng, Ning Liu, Keyan Wu, Xueli Zhang, Chengcheng Gao, Fenfen Liu, Jimeng Sun, and Chenggong Liu. 2025. "Regulatory Effects of Paclobutrazol and Uniconazole Mixture on the Morphology and Biomass Allocation of Amorpha fruticosa Seedlings" Plants 14, no. 23: 3684. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233684

APA StyleZhang, J., Liu, N., Wu, K., Zhang, X., Gao, C., Liu, F., Sun, J., & Liu, C. (2025). Regulatory Effects of Paclobutrazol and Uniconazole Mixture on the Morphology and Biomass Allocation of Amorpha fruticosa Seedlings. Plants, 14(23), 3684. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233684