Multi-Omics Analysis Unravels the Biosynthesis and Regulatory Mechanisms of Floral Scent Across Various Cultivars and Developmental Stages in Phalaenopsis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Metabolite Analysis of VOCs Reveals the Variation in Floral Scent of 10 Phalaenopsis Cultivars

2.2. Identification of VOCs Related Regulatory Factors During Different Floret Stages of Phalaenopsis Formosa Sweet Memory

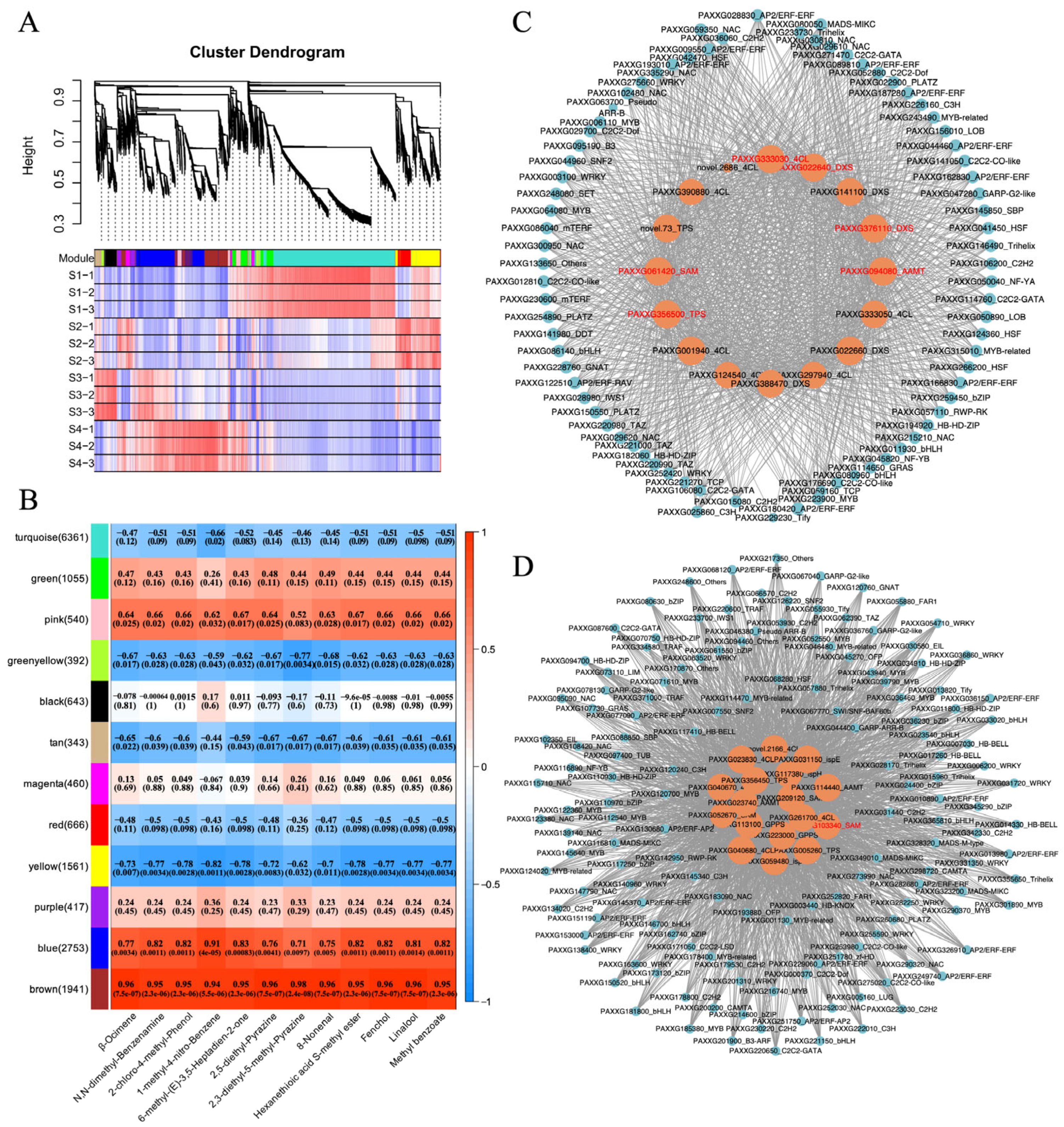

2.3. Expression of 82 TF Genes During Phalaenopsis Opening Was Positively Correlated with Aroma-Related Structural Genes

2.4. Thirty-Three Structural Genes and TF Genes Were Hub Genes Involved in the Aroma Synthesis During Phalaenopsis Flowering

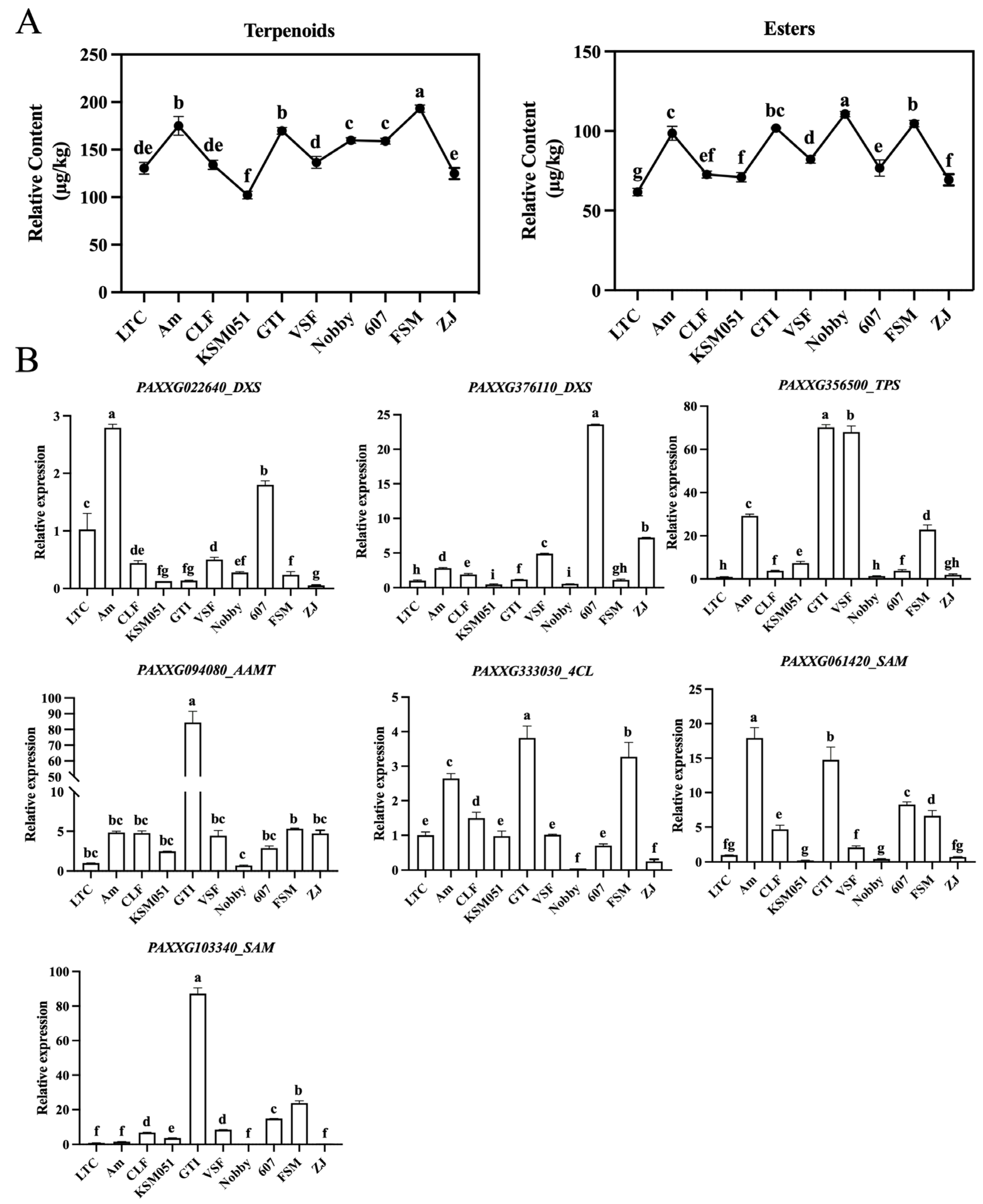

2.5. Expression Patterns of Candidate DEGs Involved in Phalaenopsis Aroma Biosynthesis

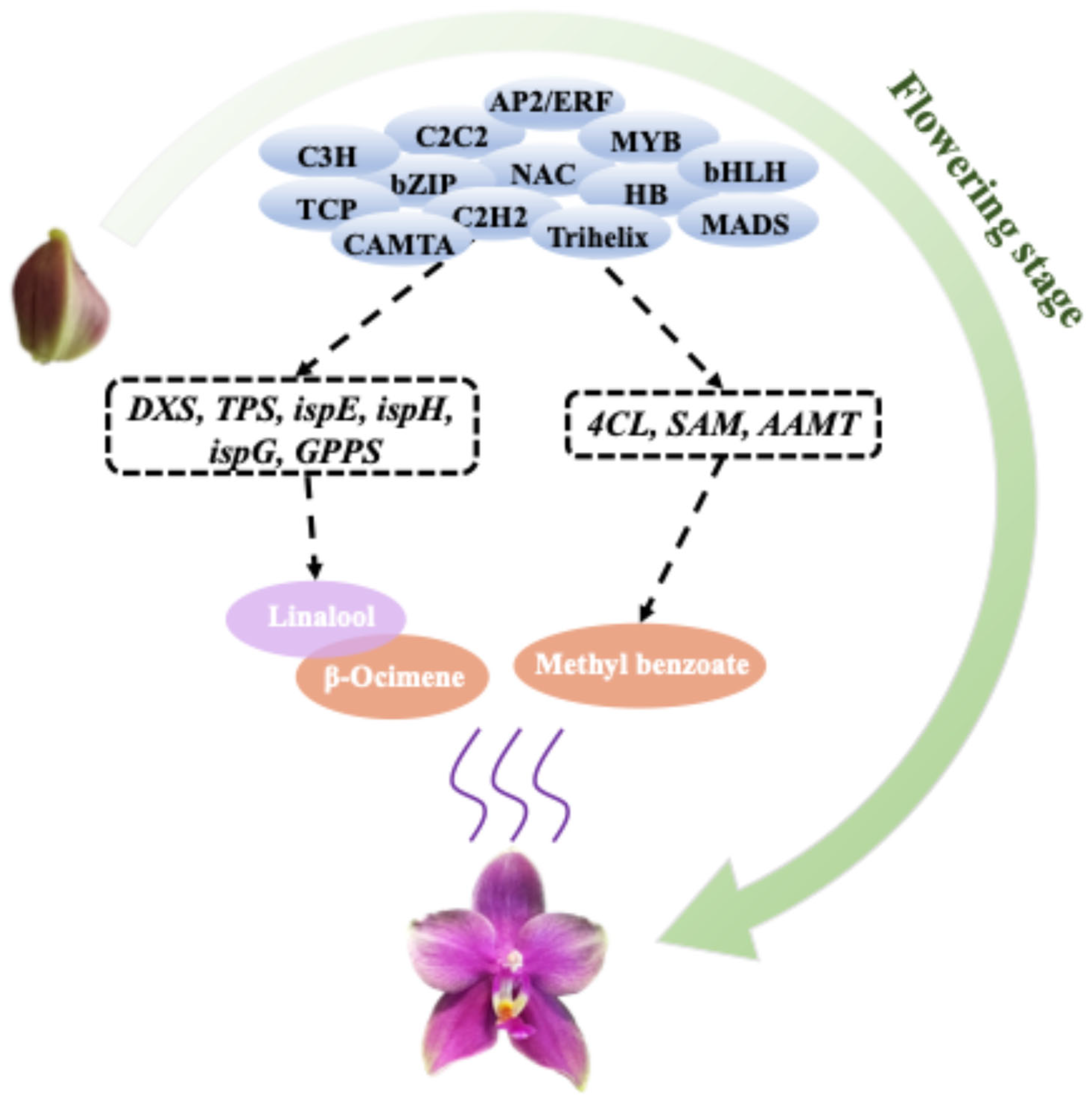

3. Discussion

3.1. The Main VOCs of Phalaenopsis Formosa Sweet Memory Were β-Ocimene, Linalool, and Methyl Benzoate

3.2. PeTPS, Pe4CL, and PeSAM May Function as Master Regulators in the Coordinated Regulation of Phalaenopsis Aroma Formation

3.3. The Formation of the Fragrance of Phalaenopsis May Be Regulated by Multiple Transcription Factors

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Collection and GC-MS/MS Analysis of VOCs

4.3. RNA Extraction and Transcriptome Sequencing

4.4. Analysis of RNA-Seq Data

4.5. qRT-PCR Assay

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Schiestl, F.P. Ecology and evolution of floral volatile-mediated information transfer in plants. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlemann, J.K.; Klempien, A.; Dudareva, N. Floral volatiles: From biosynthesis to function. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1936–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, W.; Davidovich-Rikanati, R.; Lewinsohn, E. Biosynthesis of plant-derived flavor compounds. Plant J. 2008, 54, 712–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichersky, E.; Noel, J.P.; Dudareva, N. Biosynthesis of plant volatiles: Nature’s diversity and ingenuity. Science 2006, 311, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido, P.; Perello, C.; Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. New insights into plant isoprenoid metabolism. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falara, V.; Akhtar, T.A.; Nguyen, T.T.; Spyropoulou, E.A.; Bleeker, P.M.; Schauvinhold, I.; Matsuba, Y.; Bonini, M.E.; Schilmiller, A.L.; Last, R.L.; et al. The tomato terpene synthase gene family. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 770–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholl, D. Biosynthesis and biological functions of terpenoids in plants. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2015, 148, 63–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.; Ke, Y.; Yu, R.; Yue, Y.; Amanullah, S.; Jahangir, M.M.; Fan, Y. Volatile terpenoids: Multiple functions, biosynthesis, modulation and manipulation by genetic engineering. Planta 2017, 246, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-Y.; Jeng, M.-F.; Tsai, W.-C.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Li, C.-Y.; Wu, T.-S.; Kuoh, C.-S.; Chen, W.-H.; Chen, H.-H. A novel homodimeric geranyl diphosphate synthase from the orchid Phalaenopsis bellina lacking a DD(X)2–4D motif. Plant J. 2008, 55, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Hong, S.; Jiang, X.; Lv, F. Determination of volatile components in flowers of Phalaenopsis violacea. Chin. J. Trop. Agric. 2020, 40, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, C.; Fan, Y.P. Analysis of Aroma Components of Oncidium. Acta Agric. Univ. Jiangxiensis 2012, 34, 692–698. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.L.; Wang, Y.; Tian, M.; Fan, M.H. Changes of Aroma Components in Oncidium Sharry Baby in Different Florescence and Flower Parts. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2011, 44, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhong, S.; Kong, L.; Fan, R.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, H. Emission and Transcriptional Regulation of Aroma Variation in Oncidium Twinkle ‘Red Fantasy’ Under Diel Rhythm. Plants 2024, 13, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhou, S.; Jin, Y.; Wang, W.; Xia, K.; Chen, Z. Aromatic Terpenes and Their Biosynthesis in Dendrobium, and Conjecture on the Botanical Perfumer Mechanism. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5305–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.L.; Hu, H.Z.; Yan, B.; Chen, L.Q. Advances of Researches on Biosynthesis and Regulation of Floral Volatile Benzenoids/Phenylpropanoids. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2021, 48, 1815–1826. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.J.; Cao, H.; Liao, Q.C.; Chen, D.P.; Cun, D.C.; Li, D.H.; Li, H.; Lu, L. Advances in Synthesis and Gene Regulation of Floral Scents from Dendrobium. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 26, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Z.; Hu, H.; Shi, S.; Yuan, X.; Yan, B.; Chen, L. An Update on the Function, Biosynthesis and Regulation of Floral Volatile Terpenoids. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Jin, B. Floral Scents and Fruit Aromas: Functions, Compositions, Biosynthesis, and Regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 860157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.T.; Chen, W.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Ho, H.Y.; Yeh, C.H.; Kuo, Y.T.; Su, C.L.; Yen, S.H.; Hsueh, H.Y.; Yeh, J.H.; et al. Chromosome-level assembly, genetic and physical mapping of Phalaenopsis aphrodite genome provides new insights into species adaptation and resources for orchid breeding. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 2027–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dong, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhai, J. A review for the breeding of orchids: Current achievements and prospects. Hortic. Plant J. 2021, 7, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainstein, A.; Lewinsohn, E.; Pichersky, E.; Weiss, D. Floral fragrance. New inroads into an old commodity. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.Y.; Tsai, W.C.; Chen, W.H.; Chen, H.H. Biosynthetic Regulation of Floral Scent in Phalaenopsis. In Orchid Biotechnology II; World Scientific Publishing Co.: Singapore, 2015; pp. 145–180. [Google Scholar]

- Caì, J.; Liu, X.; Vanneste, K.; Proost, S.; Tsai, W.C.; Liu, K.W.; Chen, L.J.; He, Y.; Xu, Q.; Bian, C. The genome sequence of the orchid Phalaenopsis equestris. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awano, K.; Honda, T.; Ogawa, T.; Suzuki, S.; Matsunaga, Y. Volatile components of Phalaenopsis schilleriana Rehb. f. Flavour. Fragr. J. 1997, 12, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.Y.; Tsai, W.C.; Kuoh, C.S.; Huang, T.H.; Wang, H.C.; Wu, T.S.; Leu, Y.L.; Chen, W.H.; Chen, H.H. Comparison of transcripts in Phalaenopsis bellina and Phalaenopsis equestris (Orchidaceae) flowers to deduce monoterpene biosynthesis pathway. BMC Plant Biol. 2006, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, M.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, E.; Wang, W.; Zhao, K.; Peng, D.; Zhou, Y. Volatile component analysis of new hybrid varieties of Phalaenopsis. Guihaia 2023, 43, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Y.C.; Hung, Y.C.; Tsai, W.C.; Chen, W.H.; Chen, H.H. PbbHLH4 regulates floral monoterpene biosynthesis in Phalaenopsis orchids. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 4363–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Kwon, O.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, P.; Park, P.; Choi, I.; Lee, H.; Yoo, J. Breeding of Yellow Small-Type Phalaenopsis ‘Yellow Scent’ with Fragrance. Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2019, 32, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Lv, F. Analysis of volatile components in flowers of four different Phalaenopsis germplasm resources by headspace solid phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. China Agric. Univ. 2021, 26, 38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Tian, J.; Xie, D.; Lin, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liao, X.; Wu, Z. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses provide insight into the variation of floral scent and molecular regulation in different cultivars and flower development of Curcuma alismatifolia. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, D.R. Evolution of flavors and scents. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagegowda, D.A. Plant volatile terpenoid metabolism: Biosynthetic genes, transcriptional regulation and subcellular compartmentation. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 2965–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, K.; Wu, Q.; Lu, X.; Lu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Qiu, S. Combined Analysis of Volatile Compounds and Extraction of Floral Fragrance Genes in Two Dendrobium Species. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Guo, Y.; Shi, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, M. Overexpression of LiTPS2 from a cultivar of lily (Lilium ‘Siberia’) enhances the monoterpenoids content in tobacco flowers. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, F.; Ke, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Y.; Waseem, M.; Ashraf, U.; Li, X.; Yu, R.; Fan, Y. Genome-wide analysis of ARF transcription factors reveals HcARF5 expression profile associated with the biosynthesis of β-ocimene synthase in Hedychium coronarium. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, A.; Jowkar, A.; Chehrazi, M.; Moghadam, A.; Karami, A. Fragrance and color production from corona and perianth of Iranian narcissus (Narcissus tazetta L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 212, 118368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, S.; Yan, H.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, J.; Henry, R.J. Integrated multi-omics analysis unravels the floral scent characteristics and regulation in “Hutou” multi-petal jasmine. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y. Composition and Emission Rhythm of Floral Scent Volatiles from Eight Lily Cut Flowers. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Science. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2012, 137, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington-Rauth, M.C.; Ramírez, S.R. Evolution and diversity of floral scent chemistry in the euglossine bee-pollinated orchid genus Gongora. Ann. Bot. 2016, 118, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H. Study on the Volatile, Characteristic Floral Fragrance Components of Chinese Cymbidium; Chinese Academy of Forestry: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Y.C.; Lee, M.C.; Chang, Y.L.; Chen, W.H.; Chen, H.H. Diurnal regulation of the floral scent emission by light and circadian rhythm in the Phalaenopsis orchids. Bot. Stud. 2017, 58, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colinas, M.; Goossens, A. Combinatorial Transcriptional Control of Plant Specialized Metabolism. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Liu, B.; Li, M.; Gao, X.; Fang, Q.; Liu, C.; Ding, H.; Wang, L.; Gao, X. Identification and characterization of terpene synthase genes accounting for volatile terpene emissions in flowers of Freesia x hybrida. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 4249–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Liu, C.; Zheng, R.; Cai, X.; Luo, J.; Zou, J.; Wang, C. Emission and Accumulation of Monoterpene and the Key Terpene Synthase (TPS) Associated with Monoterpene Biosynthesis in Osmanthus fragrans Lour. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, F.; Ke, Y.; Yu, R.; Fan, Y. Functional characterization and expression analysis of two terpene synthases involved in floral scent formation in Lilium ‘Siberia’. Planta 2019, 249, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Kuo, Y.W.; Chuang, Y.C.; Yang, Y.P.; Huang, L.M.; Jeng, M.F.; Chen, W.H.; Chen, H.H. Terpene Synthase-b and Terpene Synthase-e/f Genes Produce Monoterpenes for Phalaenopsis bellina Floral Scent. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 700958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Sun, T.; Xu, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, L. Gene clone and expression analysis of 4-coumarate-CoA ligase in Sweet Osmanthus (Osmanthus fragrans Lour.). Mol. Plant Breed. 2016, 3, 536–541. [Google Scholar]

- Rui, C.; Dao-cheng, M.; Huan, X.; Tiao-hong, F.; Wen-han, C. Cloning, Sequencing and Expression Analysis of Rosa multiflora Rm4CL Gene. North. Hortic. 2022, 17, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, M.; Liu, N.; He, Z.-S.; Dong, X.-M.; Gao, T.-Y.; Zhu, A.; Yang, J.-B.; Zhang, S.-B. Integrative omics reveals mechanisms of biosynthesis and regulation of floral scent in Cymbidium tracyanum. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 2162–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhong, J.; Liang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, M. Positive regulatory role of R2R3 MYBs in terpene biosynthesis in Lilium ‘Siberia’. Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 1024–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Yu, G.; Qing, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C. Petunia bZIP transcription factor PhbZIP3 is involved in floral volatile benzenoid/phenylpropanoid biosynthesis through regulating the expression of PhPAL2 and PhBSMT. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 326, 112719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Jiang, M.Y.; Zhu, L.L.; Zeng, X.M.; Ju, H.; Yang, Q.L.; Zhang, T.Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Zheng, R.R. OfWRKY33 binds to the promoter of key linalool synthase gene OfTPS7 to stimulate linalool synthesis in Osmanthus fragrans flowers. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varet, H.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Coppée, J.Y.; Dillies, M.A. SARTools: A DESeq2- and EdgeR-Based R Pipeline for Comprehensive Differential Analysis of RNA-Seq Data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Shen, S.; Zhou, S.; Li, Y.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shi, Y.; An, L.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, W.; et al. Rice metabolic regulatory network spanning the entire life cycle. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiao, C.; Sun, H.; Rosli, H.G.; Pombo, M.A.; Zhang, P.; Banf, M.; Dai, X.; Martin, G.B.; Giovannoni, J.J.; et al. iTAK: A Program for Genome-wide Prediction and Classification of Plant Transcription Factors, Transcriptional Regulators, and Protein Kinases. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 1667–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, S.; He, J.; Lin, B.; Wu, J.; Fan, R. Multi-Omics Analysis Unravels the Biosynthesis and Regulatory Mechanisms of Floral Scent Across Various Cultivars and Developmental Stages in Phalaenopsis. Plants 2025, 14, 3682. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233682

Zhong H, Chen Y, Zhong S, He J, Lin B, Wu J, Fan R. Multi-Omics Analysis Unravels the Biosynthesis and Regulatory Mechanisms of Floral Scent Across Various Cultivars and Developmental Stages in Phalaenopsis. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3682. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233682

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Huaiqin, Yan Chen, Shengyuan Zhong, Jun He, Bing Lin, Jianshe Wu, and Ronghui Fan. 2025. "Multi-Omics Analysis Unravels the Biosynthesis and Regulatory Mechanisms of Floral Scent Across Various Cultivars and Developmental Stages in Phalaenopsis" Plants 14, no. 23: 3682. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233682

APA StyleZhong, H., Chen, Y., Zhong, S., He, J., Lin, B., Wu, J., & Fan, R. (2025). Multi-Omics Analysis Unravels the Biosynthesis and Regulatory Mechanisms of Floral Scent Across Various Cultivars and Developmental Stages in Phalaenopsis. Plants, 14(23), 3682. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233682