Optimization of N-P-K Nutrient Ratios for Three Leafy Vegetables Using Response Surface Methodology and Principal Component Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

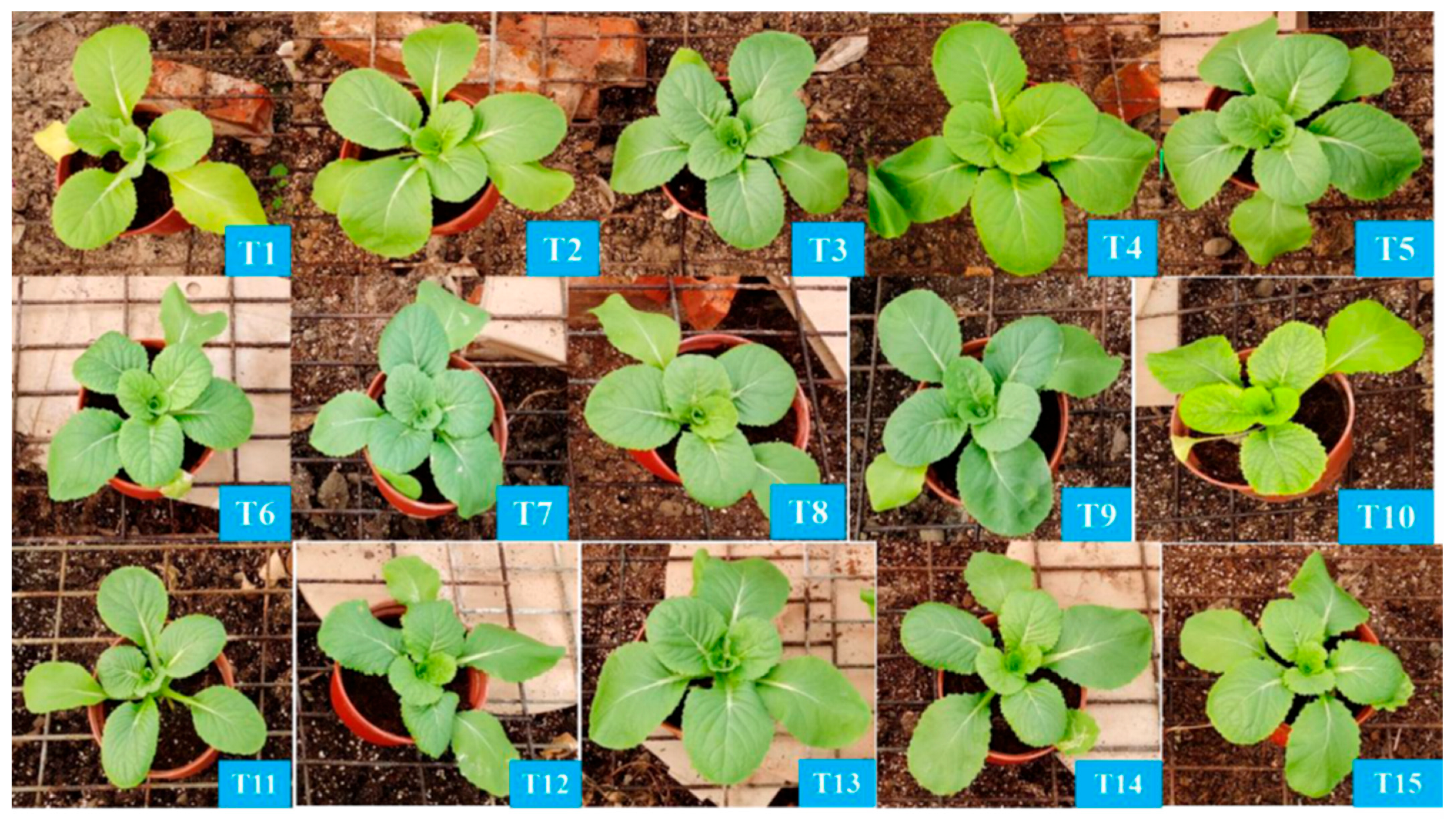

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. Fertilizer Treatments and Application

2.3. Screening Experiment and Measurements

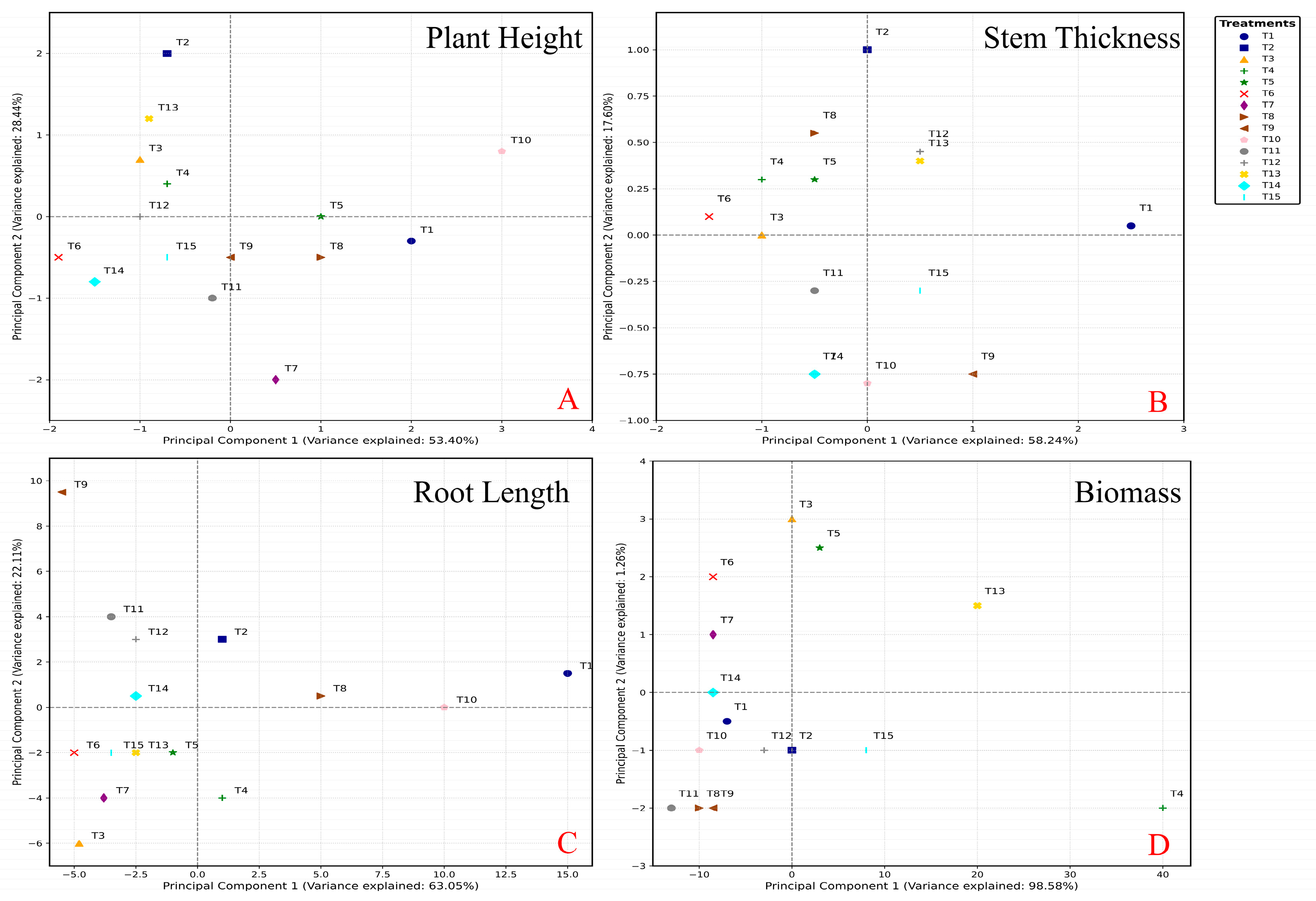

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Spinach N-P-K Formula

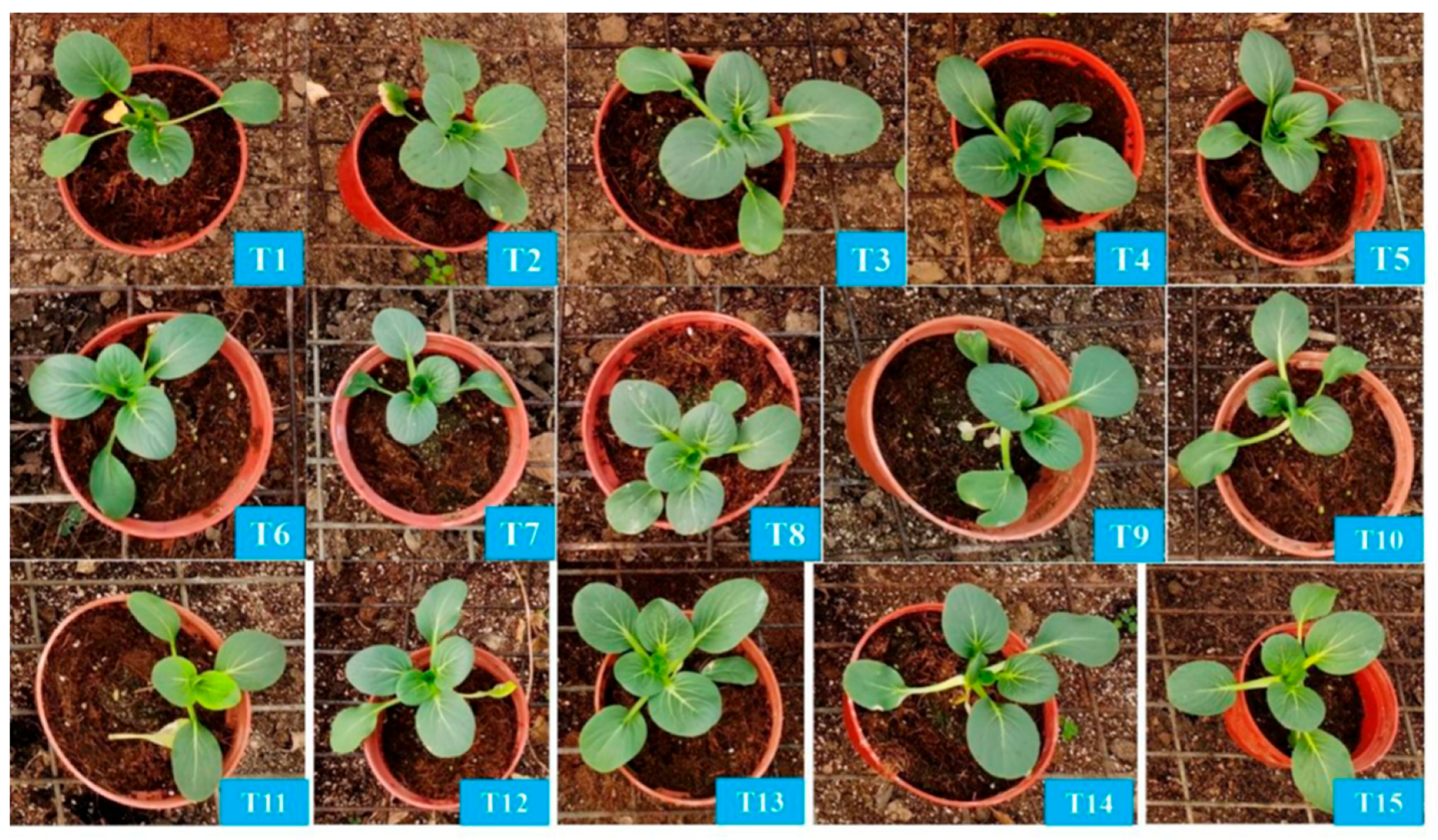

3.2. Bok Choy N-P-K Formula

3.3. Chinese Cabbage N-P-K Formula

3.4. N-P-K and Plant Growth

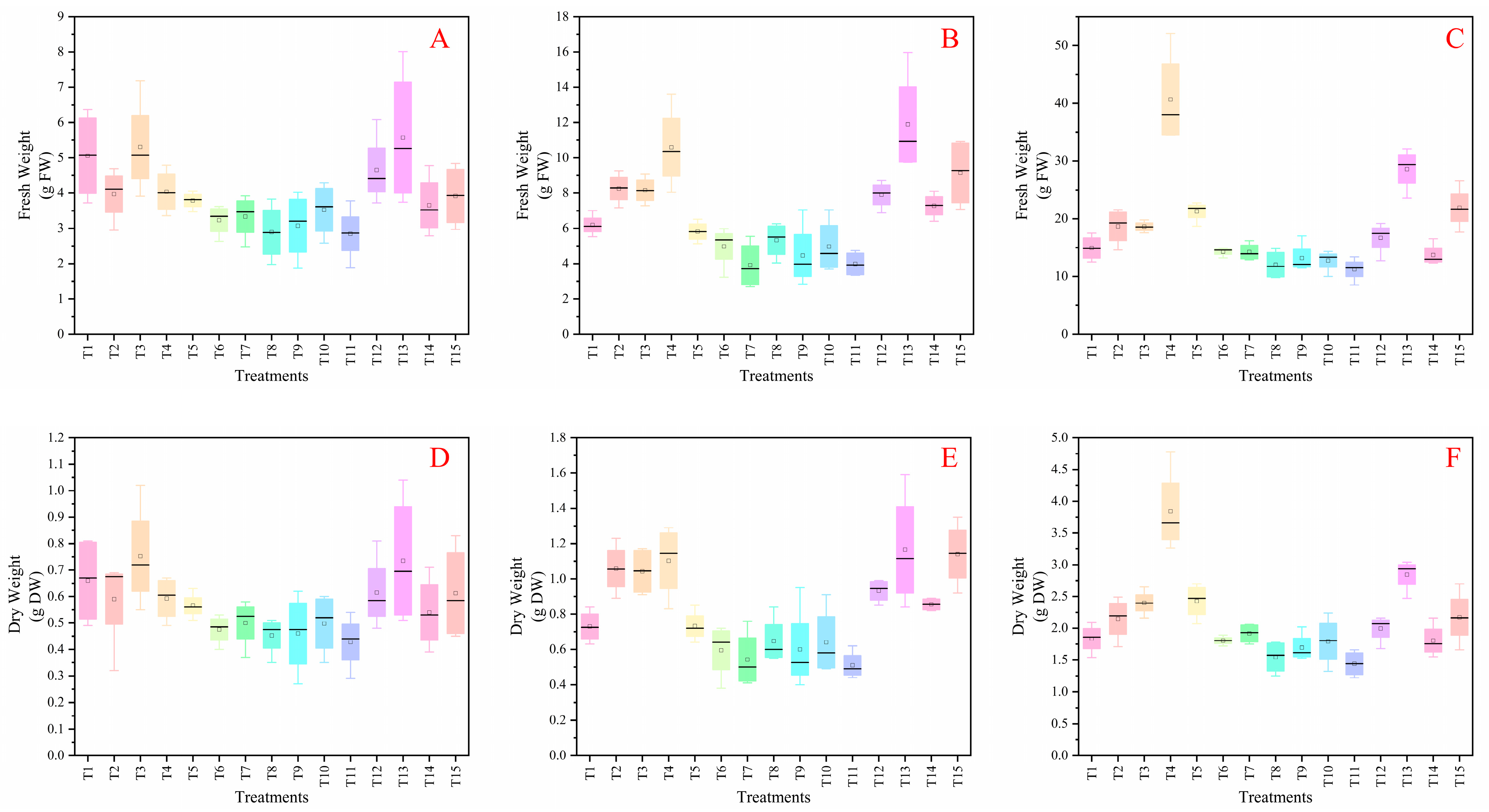

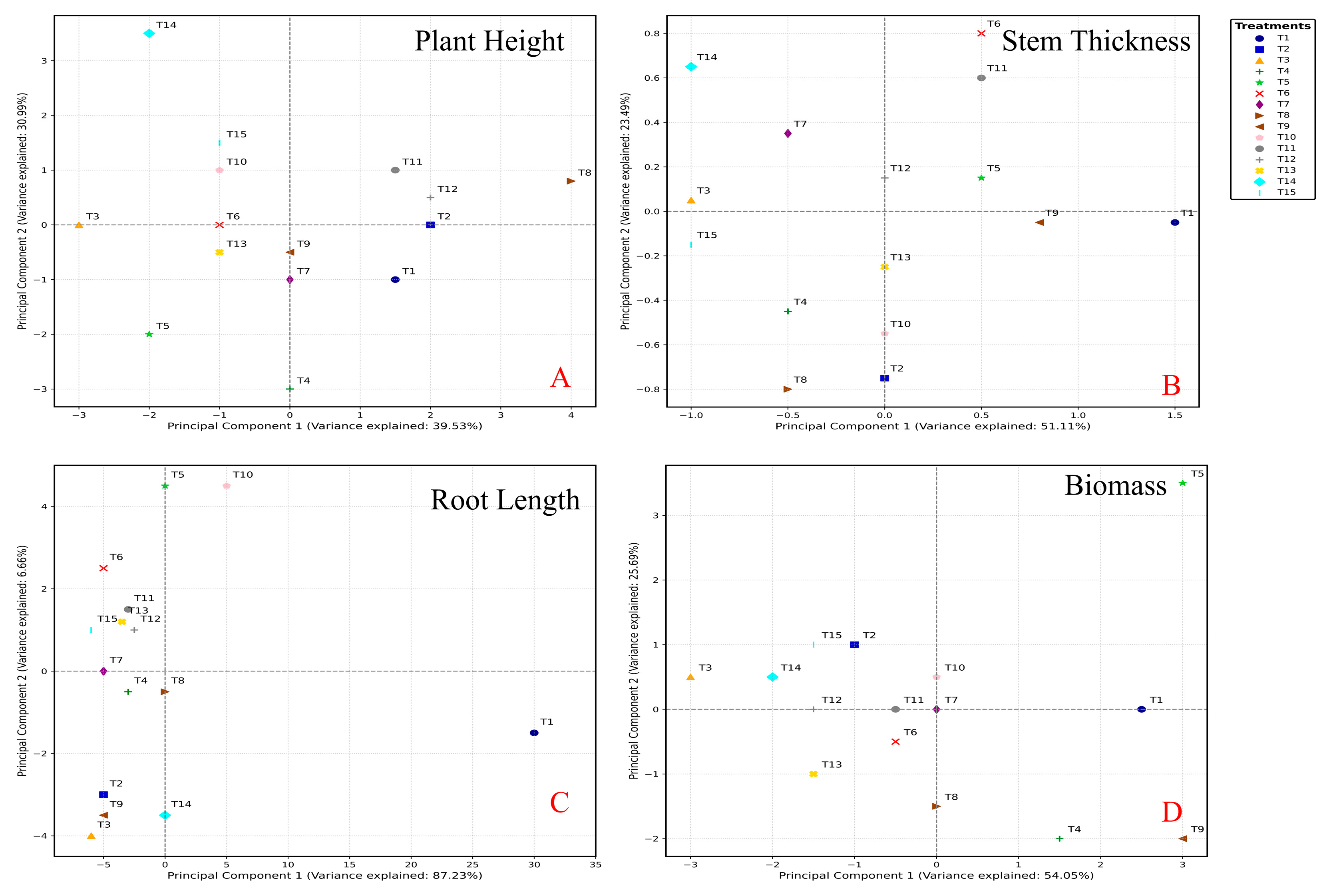

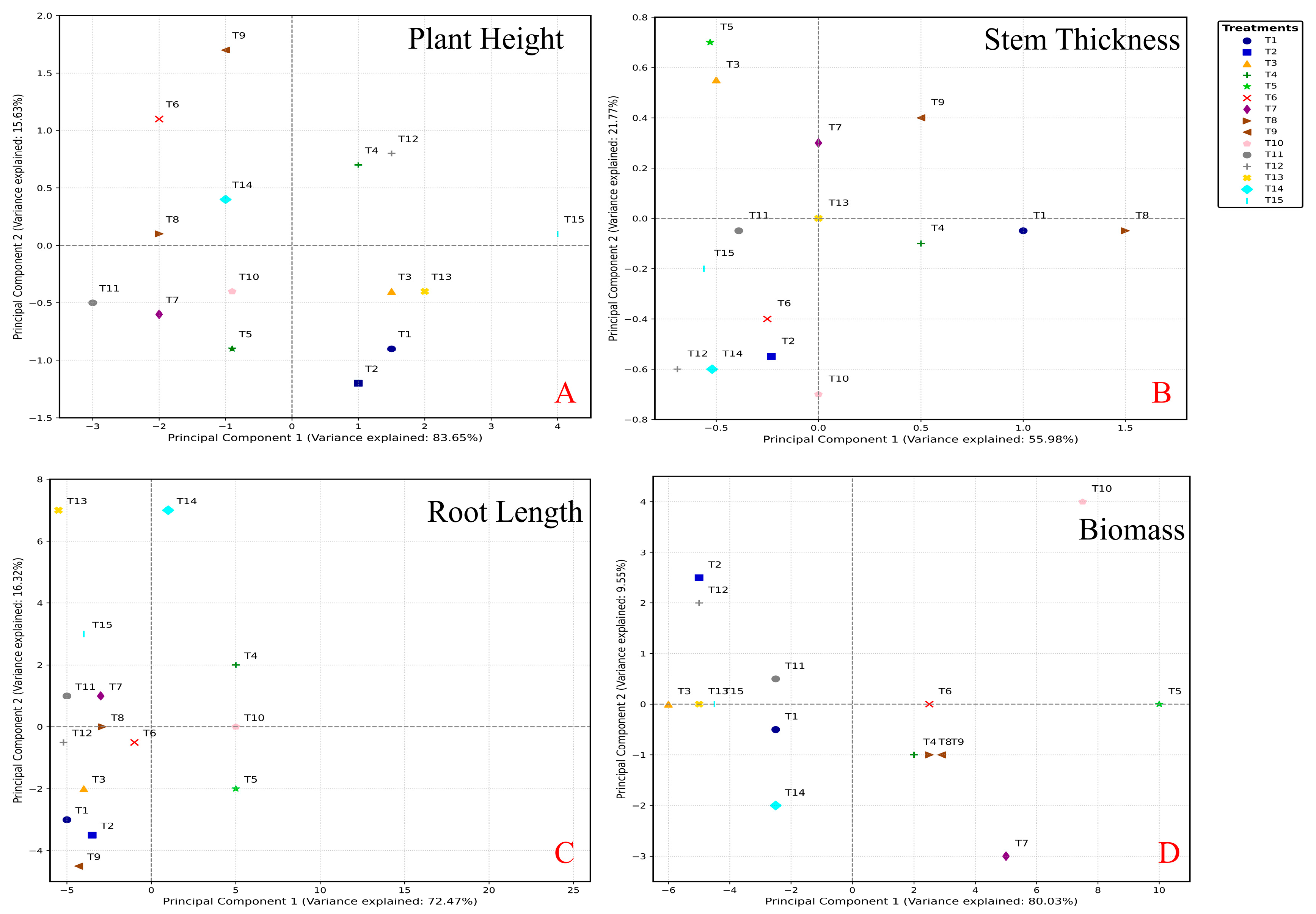

3.5. Statistical Analysis for Screening Optimization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, M.N.; Mobin, M.; Abbas, Z.K.; Alamri, S.A. Fertilizers and their contaminants in soils, surface and groundwater. Encycl. Anthr. 2018, 5, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divito, G.A.; Sadras, V.O. How do phosphorus, potassium and sulphur affect plant growth and biological nitrogen fixation in crop and pasture legumes? A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2014, 156, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.J. Soil erosion, climate change and global food security: Challenges and strategies. Sci. Prog. 2014, 97, 97–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanda, P.Z.; Yatich, T.; Ochola, W.O.; Ngece, N. Natural resource management in the context of climate change. In Managing Natural Resources for Development in Africa: A Resource Book; University of Nairobi Press: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010; p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- Dobermann, A.; Bruulsema, T.; Cakmak, I.; Gerard, B.; Majumdar, K.; McLaughlin, M.; Reidsma, P.; Vanlauwe, B.; Wollenberg, L.; Zhang, F.; et al. Responsible plant nutrition: A new paradigm to support food system transformation. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 33, 100636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morizet-Davis, J.; Marting Vidaurre, N.A.; Reinmuth, E.; Rezaei-Chiyaneh, E.; Schlecht, V.; Schmidt, S.; Singh, K.; Vargas-Carpintero, R.; Wagner, M.; von Cossel, M. Ecosystem Services at the Farm Level—Overview, Synergies, Trade-Offs, and Stakeholder Analysis. Glob. Chall. 2023, 7, 2200225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaparapu, J.; Pragada, P.M.; Geddada, M.N.R. Fruits and vegetables and its nutritional benefits. In Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals: Bioactive Components, Formulations and Innovations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanda, D.T.; Guinée, J.B.; Tukker, A. The second green revolution: Innovative urban agriculture’s contribution to food security and sustainability—A review. Glob. Food Secur. 2019, 22, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemadodzi, L.E.; Araya, H.; Nkomo, M.; Ngezimana, W.; Mudau, N.F. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium effects on the physiology and biomass yield of baby spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). J. Plant Nutr. 2017, 40, 2033–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Xu, F.; Chen, G.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Du, L.; Ding, G. Evaluation of the effects of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium applications on the growth, yield, and quality of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Agronomy 2022, 12, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E.; Delaune, T.; Silva, J.V.; Descheemaeker, K.; van de Ven, G.; Schut, A.G.; van Wijk, M.; Hammond, J.; Hochman, Z.; Taulya, G.; et al. The future of farming: Who will produce our food? Food Secur. 2021, 13, 1073–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Cai, Y. Problems, challenges, and strategic options of grain security in China. Adv. Agron. 2009, 103, 101–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buturi, C.V.; Mauro, R.P.; Fogliano, V.; Leonardi, C.; Giuffrida, F. Mineral Biofortification of Vegetables as a Tool to Improve Human Diet. Foods 2021, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Vanga, S.K.; Saxena, R.; Orsat, V.; Raghavan, V. Effect of climate change on the yield of cereal crops: A review. Climate 2018, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, M.A.N.; Alari, F.O.; Ferreira, M.M.C.; do Amaral, L.R. Influence of soil sample preparation on the quantification of NPK content via spectroscopy. Geoderma 2019, 338, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, Y.P.; Yang, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, C.; Yan, J. Interactive effects of nitrogen and phosphorus additions on plant growth vary with ecosystem type. Plant Soil 2019, 440, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggio, G.M.; Jones, S.L.; Gibson, K.E. Risk of human pathogen internalization in leafy vegetables during lab-scale hydroponic cultivation. Horticulturae 2019, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Mor, V.S.; Tokas, J.; Punia, H.; Malik, S.; Malik, K.; Sangwan, S.; Tomar, S.; Singh, P.; Singh, N.; et al. Biostimulant-treated seedlings under sustainable agriculture: A global perspective facing climate change. Agronomy 2020, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fess, T.L.; Kotcon, J.B.; Benedito, V.A. Crop breeding for low input agriculture: A sustainable response to feed a growing world population. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1742–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Subramanian, P.; Hahn, B.S. Glucosinolate Diversity Analysis in Spinach (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis var. parachinensis) Germplasms for Functional Food Breeding. Foods 2023, 12, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laczi, E.; Apahidean, A.; Luca, E.; Dumitraş, A.; Boancă, P. Headed Chinese cabbage growth and yield influenced by different manure types in organic farming system. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 43, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Takeuchi, W. Bio-Geophysical Suitability Mapping for Chinese Cabbage of East Asia from 2001 to 2020. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y.; Kim, D.G.; Park, J.T.; Kandpal, L.M.; Hong, S.J.; Cho, B.K.; Lee, W.H. Physicochemical quality changes in Chinese cabbage with storage period and temperature: A review. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 41, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, L.M.; Ho, E.; Obeid, R.; Tzoulis, C.; Green, M.; Huber, L.G.; Stout, M.; Griffiths, J.C. Advancing nutrition science to meet evolving global health needs. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Tang, B.; Shen, Y. The Role of biochar nanoparticles performing as nanocarriers for fertilizers on the growth promotion of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa (Pekinensis Group)). Coatings 2022, 12, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.D.; Akiyama, T. A rapid method of measuring leaf area. Weed Sci. 1963, 11, 266–268. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.L.; Dijak, M.; Bulman, P. Determination of dry weight per unit leaf area: A comparison of techniques. Crop Sci. 1988, 28, 837–839. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, R. Plant Growth Analysis; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issifu, M.; Naitchede, L.H.S.; Ateka, E.M.; Onguso, J.; Ngumi, V.W. Synergistic effects of substrate inoculation with Pseudomonas strains on tomato phenology, yield, and selected human health-related phytochemical compounds. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 2023, 6, e20435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbisa, A. Toward the recent advances in nutrient use efficiency (NUE): Strategies to improve phosphorus availability to plants. In Sustainable Crop Production-Recent Advances; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; Volume 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, W.; Xu, Z.; Wang, L.; Ma, L. Yield, nitrogen use efficiency and economic benefits of biochar additions to Chinese Flowering Cabbage in Northwest China. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2019, 113, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leghari, S.J.; Wahocho, N.A.; Laghari, G.M.; HafeezLaghari, A.; MustafaBhabhan, G.; HussainTalpur, K. Role of nitrogen for plant growth and development: A review. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2016, 10, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, H.; Vandana; Sharma, S.; Pandey, R. Phosphorus nutrition: Plant growth in response to deficiency and excess. In Plant Nutrients and Abiotic Stress Tolerance; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Hazra, K.K.; Nath, C.P.; Praharaj, C.S.; Singh, U. Grain legumes for resource conservation and agricultural sustainability in South Asia. In Legumes for Soil Health and Sustainable Management; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, R.; Su, H.; Lai, J.; Sheng, Y.; Shen, Y. Optimization of N-P-K Nutrient Ratios for Three Leafy Vegetables Using Response Surface Methodology and Principal Component Analysis. Plants 2025, 14, 3681. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233681

Yang R, Su H, Lai J, Sheng Y, Shen Y. Optimization of N-P-K Nutrient Ratios for Three Leafy Vegetables Using Response Surface Methodology and Principal Component Analysis. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3681. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233681

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Ruiping, Hao Su, Jiangshan Lai, Yu Sheng, and Yu Shen. 2025. "Optimization of N-P-K Nutrient Ratios for Three Leafy Vegetables Using Response Surface Methodology and Principal Component Analysis" Plants 14, no. 23: 3681. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233681

APA StyleYang, R., Su, H., Lai, J., Sheng, Y., & Shen, Y. (2025). Optimization of N-P-K Nutrient Ratios for Three Leafy Vegetables Using Response Surface Methodology and Principal Component Analysis. Plants, 14(23), 3681. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233681