Carbon Sequestration, Plant Cover, and Soil Health: Strategies to Mitigate Climate Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Carbon Sequestration in Vineyards

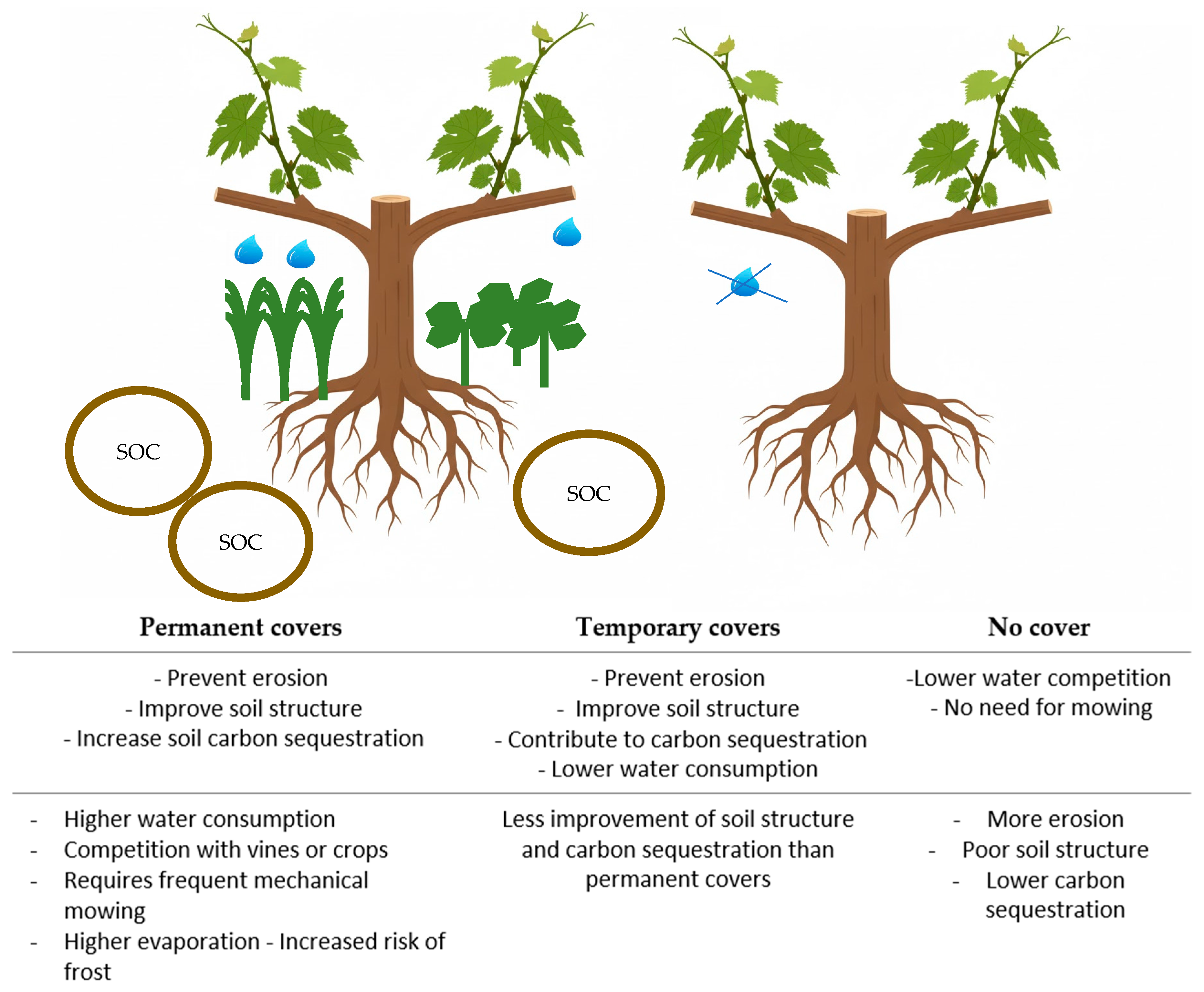

3. Plant Covers in Vineyards

4. Permanent vs. Short-Cycle Plant Covers

5. Soil Health and Resistance to Climate Change

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Villat, J.; Nicholas, K.A. Quantifying soil carbon sequestration from regenerative agricultural practices in crops and vineyards. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 7, 1234108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.P.; da Silva, J.C.E. Evaluation of the carbon footprint of the life cycle of wine production: A review. Clean. Circ. Bioeconomy 2022, 2, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, J.A.; Bohrer, G.; Ju, Y.; Wrighton, K.; Johnson, N.; Kinsman-Costello, L. Carbon sequestration and nitrogen and phosphorus accumulation in a freshwater, estuarine marsh: Effects of microtopography and nutrient loads. Geoderma 2023, 430, 116349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, M.U.F. Will changes in soil organic carbon act as a positive or negative feedback on global warming? Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Lehmann, J.; Ogle, S.; Reay, D.; Robertson, G.P.; Smith, P. Climate-smart soils. Nature 2016, 532, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.; Bossio, D.A.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Rillig, M.C. The concept and future prospects of soil health. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aguilera, E.; Lassaletta, L.; Gattinger, A.; Gimeno, B.S. Managing soil carbon for climate change mitigation and adaptation in Mediterranean cropping systems: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 168, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, J.N.J.; Lines, T.E.P.; Penfold, C.; Cavagnaro, T.R. Cover crops and carbon stocks: How under-vine management influences SOC inputs and turnover in two vineyards. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 831, 154800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Recarbonizing Global Soils—A Technical Manual of Recommended Management Practices; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchoms, S.; Wang, Z.; Vanacker, V.; Van Oost, K. Evaluating the effects of soil erosion and productivity decline on soil carbon dynamics using a model-based approach. SOIL 2019, 5, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, W.M.; Kwon, K.C. Soil carbon sequestration and land-use change: Processes and potential. Glob. Change Biol. 2000, 6, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, D.; Dangi, S.R.; Duan, Y.; Pflaum, T.; Gartung, J.; Qin, R.; Turini, T. Nitrogen dynamics affected by biochar and irrigation level in an onion field. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 714, 136432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janzen, H.H.; Fixen, P.E.; Franzluebbers, A.J.; Hattey, J.A.; Izaurralde, R.C.; Ketterings, Q.M.; Schlesinger, W.H. Soil carbon and nitrogen interactions and their potential to mitigate climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2979–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Soussana, J.-F.; Angers, D.; Schipper, L.; Chenu, C.; Rasse, D.P.; Batjes, N.H.; van Egmond, F.; McNeill, S.; Kuhnert, M.; et al. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realize the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazcano, C.; Gonzalez-Maldonado, N.; Yao, E.H.; Wong, C.T.F.; Falcone, M.; Peterson, J.D.; Casassa, L.F.; Malama, B.; Decock, C. Erratum to “Assessing the short-term effects of no-till on crop yield, greenhouse gas emissions, and soil C and N pools in a cover-cropped, biodynamic Mediterranean vineyard”. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2023, 1, e8100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumkeller, M.; Yu, R.; Torres, N.; Marigliano, L.E.; Zaccaria, D.; Kurtural, S.K. Site characteristics determine the effectiveness of tillage and cover crops on the net ecosystem carbon balance in California vineyard agroecosystems. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1024606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.B.; Gifford, R.M. Soil carbon stocks and land use change: A meta analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2002, 8, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.W.; Zeiss, M.R. Soil health and sustainability: Managing the biotic component of soil quality. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2000, 15, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, L.A.; Berli, F.; Fontana, A.; Bottini, R.; Piccoli, P. Climate Change Effects on Grapevine Physiology and Biochemistry: Benefits and Challenges of High Altitude as an Adaptation Strategy. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 835425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Shi, X.; Peng, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, R.; et al. The dynamics of wild Vitis species in response to climate change facilitate the breeding of grapevine and its rootstocks with climate resilience. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnelli, A.; Bol, R.; Trumbore, S.E.; Dixon, L.; Cocco, S.; Corti, G. Carbon and nitrogen in soil and vine roots in harrowed and grass-covered vineyards. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 193, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, D.; Carlisle, E.; Spencer, R. Carbon Flow Through Root and Microbial Respiration in Vineyards and Adjacent Oak Woodland Grassland Communities. 2001–2006 Mission Kearney Foundation of Soil Science: Soil Carbon and Californias Terrestrial Ecosystems Final Report 2001018. 2007. Available online: https://kearney.ucdavis.edu/OLD%20MISSION/2001%20final%20reports-research%20projects/2001018Smart_FINALkms.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Kroodsma, D.A.; Field, C.B. Carbon sequestration in California agriculture, 1980–2000. Ecol. Appl. 2006, 16, 1975–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, E.; Farina, R.; Biasi, R. Sustainable viticulture: The carbon-sink function of the vineyard agro-ecosystem. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 223, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, C.; Osmond, D.; Heitman, J.; Ricker, M.; Miller, G.; Wills, S. Comparison of soil health metrics for a Cecil soil in the North Carolina Piedmont. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 978–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norkaew, S.; Miles, R.J.; Brandt, D.K.; Anderson, S.H. Effects of 130 Years of Selected Cropping Management Systems on Soil Health Properties for Sanborn Field. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2019, 83, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosdocimi, M.; Cerdà, A.; Tarolli, P. Soil water erosion on Mediterranean vineyards: A review. CATENA 2016, 141, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamabolo, E.; Gaigher, R.; Pryke, J.S. Unravelling the effects of vineyard inter-row vegetation on soil biodiversity in South Africa. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 393, 109842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, F.T.; Sykes, A.; Aitkenhead, M.; Alexander, P.; Moran, D.; MacLeod, M. Soil organic carbon sequestration rates in vineyard agroecosystems under different soil management practices: A meta-analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Díaz, A.; Marqués, M.J.; Sastre, B.; Bienes, R. Labile and stable soil organic carbon and physical improvements using groundcovers in vineyards from central Spain. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 621, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zong, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhou, J.; Jin, Y.; Zou, J. Response of soil carbon dioxide fluxes, soil organic carbon and microbial biomass carbon to biochar amendment: A meta-analysis. GCB Bioenergy 2015, 7, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Colmenero, M.; Bienes, R.; Marques, M.J. Effect of cover crops manage-ment in aggregate stability of a vineyard in Central spain. In Geophysical Research Abstracts 2010; EGU2010-14186-3; EGU General Assembly: Vienna, Austria, 2010; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, P.; Le Cadre, E.; Blanchart, E.; Hinsinger, P.; Villenave, C. Organic viticulture and soil quality: A long-term study in Southern France. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2011, 50, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldon, J.; Gershenson, A. Effects of Cultivation and Alternative Vineyard Management Practices on Soil Carbon Storage in Diverse Mediterranean Landscapes: A Review of the Literature. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2015, 39, 516–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, E.; Dobrei, A.G.; Camen, D.; Sala, F.; Prundeanu, H. N2O, CO2, Production, and C Sequestration in Vineyards: A Review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, F.; López, R.; Olego, M.Á. The Health of Vineyard Soils: Towards a Sustainable Viticulture. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S.O.; Mutegi, J.K.; Hansen, E.M.; Munkholm, L.J. Tillage effects on N2O emissions as influenced by a winter cover crop. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, G.; Marchesini, E.; Reggiani, N.; Montepaone, G.; Schiatti, P.; Sommaggio, D. Habitat management of organic vineyard in Northern Italy: The role of cover plants management on arthropod functional biodiversity. Bull. Èntomol. Res. 2016, 106, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlat, R.; Chaussod, R. Long-term Additions of Organic Amendments in a Loire Valley Vineyard. I. Effects on Properties of a Calcareous Sandy Soil. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 59, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genesio, L.; Miglietta, F.; Baronti, S.; Vaccari, F.P. Biochar increases vineyard productivity without affecting grape quality: Results from a four years field experiment in Tuscany. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 201, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Orenes, F.; Roldán, A.; Morugán-Coronado, A.; Linares, C.; Cerdà, A.; Caravaca, F. Organic Fertilization in Traditional Mediterranean Grapevine Orchards Mediates Changes in Soil Microbial Community Structure and Enhances Soil Fertility. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 1622–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiotti, F.; Marcuzzo, P.; Belfiore, N.; Lovat, L.; Fornasier, F.; Tomasi, D. Influence of compost addition on soil properties, root growth and vine performances of Vitis vinifera cv Cabernet sauvignon. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Yu, R.; Kurtural, S.K. Inoculation with Mycorrhizal Fungi and Irrigation Management Shape the Bacterial and Fungal Communities and Networks in Vineyard Soils. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Wang, H. A simple method using an allometric model to quantify the carbon sequestration capacity in vineyards. Plants 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenwerth, K.L.; Belina, K.M. Cover crops enhance soil organic matter, carbon dynamics and microbiological function in a vineyard agroecosystem. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 40, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, B.; Steenwerth, K. Influence of Floor Management Technique on Grapevine Growth, Disease Pressure, and Juice and Wine Composition: A Review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2012, 63, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, Q.; Lu, Q.; Jia, J.; Cui, B.; Liu, X. Depth-distribution patterns and control of soil organic carbon in coastal salt marshes with different plant covers. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longbottom, M.; Petrie, P. Role of vineyard practices in generating and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2015, 21, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xue, T.; Gao, F.; Wei, R.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, H. Carbon Storage Distribution Characteristics of Vineyard Ecosystems in Hongsibu, Ningxia. Plants 2021, 10, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goward, J. Estimating & Predicting Carbon Sequestered in a Vineyard with Soil Surveys, Spatial Data & GIS Management. Bachelor’s Thesis, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2012; pp. 39–42, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A.; Vesterdal, L.; Leifeld, J.; VAN Wesemael, B.; Schumacher, J.; Gensior, A. Temporal dynamics of soil organic carbon after land-use change in the temperate zone—Carbon response functions as a model approach. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 2415–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, A.; Schumacher, J.; Freibauer, A. Impact of tropical land-use change on soil organic carbon stocks—A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 1658–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond-Lamberty, B.; Thomson, A.M. A global database of soil respiration data. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, F.E.; Manzoni, S.; Chenu, C. Responses of soil heterotrophic respiration to moisture availability: An exploration of processes and models. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 59, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, S.R.; Pokhrel, C.P.; Thapa, L.B.; Yadav, R.K.P.; Dhital, D. Seasonal fluctuation of autotrophic and heterotrophic soil respiration in the subtropical Schima-Castanopsis forest, central Nepal. Soil Sci. Annu. 2025, 76, 203724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, F.; Eldridge, D.J.; García, C.; Png, G.K.; Bardgett, R.D.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Soil microbial diversity–biomass relationships are driven by soil carbon content across global biomes. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-M.; Chai, Q.; Dou, X.-C.; Yin, W.; Sun, Y.-L.; Hu, F.-L.; Li, H.-T.; Liu, Z.-P.; Wei, J.-G.; Xu, X.-H. Microbial mechanism of soil carbon emission reduction in maize-pea intercropping system with no tillage in arid land areas of northwestern China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1415264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.Y.; Li, M.; He, Y.H.; Du, Z.G.; Shao, J.J.; Zhang, G.D.; Zhou, L.Y.; Zhou, X.H. Effects of different levels of nitrogen fertilization on soil respiration during growing season in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum). Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2015, 39, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandé, J.A.; Stockert, C.M.; Liles, G.C.; Williams, J.N.; Smart, D.R.; Viers, J.H. From berries to blocks: Carbon stock quantification of a California vineyard. Carbon Balance Manag. 2017, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandellari, F.; Caruso, G.; Liguori, G.; Meggio, F.; Palese, A.M.; Zanotelli, D.; Celano, G.; Gucci, R.; Inglese, P.; Pitacci, A.; et al. A survey of carbon seques-tration potential of orchards and vineyards in Italy. Europ. J. Hort. Sci. 2016, 81, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, I.; Hontoria, C.; Gabriel, J.L.; Alonso-Ayuso, M.; Quemada, M. Cover crops to mitigate soil degradation and enhance soil functionality in irrigated land. Geoderma 2018, 322, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basche, A.D.; Miguez, F.E.; Kaspar, T.C.; Castellano, M.J. Do cover crops increase or decrease nitrous oxide emissions? A meta-analysis. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2014, 69, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarraonaindia, I.; Owens, S.M.; Weisenhorn, P.; West, K.; Hampton-Marcell, J.; Lax, S.; Bokulich, N.A.; Mills, D.A.; Martin, G.; Taghavi, S.; et al. The Soil Microbiome Influences Grapevine-Associated Microbiota. mBio 2015, 6, e02527-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z. Meta-analysis shows positive effects of plant diversity on microbial biomass and respiration. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giffard, B.; Winter, S.; Guidoni, S.; Nicolai, A.; Castaldini, M.; Cluzeau, D.; Coll, P.; Cortet, J.; Le Cadre, E.; D’eRrico, G.; et al. Vineyard Management and Its Impacts on Soil Biodiversity, Functions, and Ecosystem Services. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 850272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, P.; Spain, A.; Blouin, M.; Brown, G.; Decaëns, T.; Grimaldi, M.; Jiménez, J.J.; McKey, D.; Mathieu, J.; Velasquez, E.; et al. Ecosystem Engineers in a Self-organized Soil: A Review of Concepts and Future Research Questions. Soil Sci. 2016, 181, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, J.; de Mendoza, I.H.; Marín, D.; Orcaray, L.; Santesteban, L.G. Cover crops in viticulture. A systematic review (1): Implications on soil characteristics and biodiversity in vineyard. OENO One 2021, 55, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capri, C.; Gatti, M.; Fiorini, A.; Ardenti, F.; Tabaglio, V.; Poni, S. A comparative study of fifteen cover crop species for orchard soil management: Water uptake, root density traits and soil aggregate stability. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M.; Scott, N.; Shrestha, A.; Gao, S.; Hale, L. A native plant species cover crop positively impacted vineyard water dynamics, soil health, and vine vigor. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 367, 108972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novara, A.; Cerda, A.; Barone, E.; Gristina, L. Cover crop management and water conservation in vineyard and olive orchards. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 208, 104896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Salimi, K.; Rosa, D.; Hart, M. Screening Cover Crops for Utilization in Irrigated Vineyards: A Greenhouse Study on Species’ Nitrogen Uptake and Carbon Sequestration Potential. Plants 2024, 13, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Alletto, L.; Cong, W.-F.; Labreuche, J.; Lamichhane, J.R. Strategies to improve field establishment of cover crops. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 44, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, T.; Penfold, C.; Marks, J.; Kesser, M.; Pagay, V.; Cavagnaro, T. Run for cover–the ‘right’ species of under-vine cover crops do not influence yield in an Australian vineyard. OENO One 2024, 58, 7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, P.R.; Porter, R.; Sanderson, G. Cover crops. In Soil, Irrigation and Nutrition; Reimpreso con Permiso de Winetitles Pty Ltd.; Winetitles: Broadview, SA, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, J.; Marín, D.; Santesteban, L.G.; Cibriain, J.F.; Sagüés, A. Under-vine cover crops: Impact on weed development, yield and grape composition. OENO One 2020, 54, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, J.; Andrieux, P. Infiltration characteristics of soils in Mediterranean vineyards in Southern France. CATENA 1998, 32, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, E.; Hartmann, C.; Genet, P. Radial force development during root growth measured by photoelasticity. Plant Soil 2012, 360, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celette, F.; Gaudin, R.; Gary, C. Spatial and temporal changes to the water regime of a Mediterranean vineyard due to the adoption of cover cropping. Eur. J. Agron. 2008, 29, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandula, V.K. Italian Ryegrass (Lolium perenne ssp. multiflorum) and Corn (Zea mays) Competition. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 3914–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.R.; Baldock, J.A.; Penfold, C.; Power, S.A.; Woodin, S.J.; Smith, P.; Pendall, E. Soil organic carbon and nitrogen pools are increased by mixed grass and legume cover crops in vineyard agroecosystems: Detecting short-term management effects using infrared spectroscopy. Geoderma 2020, 379, 114619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfold, C.; Collins, C. Cover Crops and Weed Suppression. 2012. Available online: https://www.wineaustralia.com/getmedia/f3032a3f-7566-4908-9ef7-8f4af7c37b01/201206-Cover-crops-and-weed-suppression.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Peng, J.; Wei, W.; Lu, H.-C.; Chen, W.; Li, S.-D.; Wang, J.; Duan, C.-Q.; He, F. Effect of Covering Crops between Rows on the Vineyard Microclimate, Berry Composition and Wine Sensory Attributes of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (Vitis vinifera L. cv.) Grapes in a Semi-Arid Climate of Northwest China. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, G.; Cabezas, J.; Sánchez-Cuesta, R.; Lora, Á.; Bauer, T.; Strauss, P.; Winter, S.; Zaller, J.; Gómez, J. A field evaluation of the impact of temporary cover crops on soil properties and vegetation communities in southern Spain vineyards. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 272, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celette, F.; Findeling, A.; Gary, C. Competition for nitrogen in an unfertilized intercropping system: The case of an association of grapevine and grass cover in a Mediterranean climate. Eur. J. Agron. 2009, 30, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, A.; Faiello, C.; Longhi, F.; Mancuso, S.; Snowball, R. Cover crop species and their management in vineyards and olive groves. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 2002, 16, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, F.J.; Cibriáin, J.F.; Santesteban, L.G.; Marín, D.; Sagüés, A. Cubiertas bajo la línea del viñedo: Una alternativa viable al uso de herbicida o al laboreo intercepas. Enoviticultura 2019, 57, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, I.; Wang, J.; Sainju, U.M.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, F.; Khan, A. Cover Cropping Enhances Soil Microbial Biomass and Affects Microbial Community Structure: A Meta-Analysis. Geoderma 2021, 381, 114693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebhard, G.; Guzmán, G.; Gómez, J.A.; Winter, S.; Zaller, J.G.; Bauer, T.; Nicolai, A.; Cluzeau, D.; Popescu, D.; Bunea, C.; et al. Vineyard cover crop management strategies and their effect on soil properties across Europe. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e13573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Ruis, S.J. Cover crop impacts on soil physical properties: A review. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 1527–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Reynolds, W.; Drury, C. Reeb Cover crop effects on soil temperature in a clay loam soil in southwestern Ontario. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 101, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.L.; Connell, J.H. Frost protection: Fundamentals, practice, and economics. In FAO Plant Production and Protection; Paper No. 118; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Salomé, C.; Coll, P.; Lardo, E.; Metay, A.; Villenave, C.; Marsden, C.; Blanchart, E.; Hinsinger, P.; Le Cadre, E. The soil quality concept as a framework to assess management practices in vulnerable agroecosystems: A case study in Mediterranean vineyards. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Baets, S.; Poesen, J.; Meersmans, J.; Serlet, L. Cover crops and their erosion-reducing effects during concentrated flow erosion. Catena 2011, 85, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Loiskandl, W.; Kaul, H.-P.; Himmelbauer, M.; Wei, W.; Chen, L.; Bodner, G. Estimation of runoff mitigation by mor-phologically different cover crop root systems. J. Hydrol. 2016, 538, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-Romo, M.G.; Veas-Bernal, A.; Martínez-García, H.; Ibáñez-Pascual, S.; Martínez-Villar, E.; Campos-Herrera, R.; Marco-Mancebón, V.S.; Pérez-Moreno, I. Effects of Ground Cover Management on Insect Predators and Pests in a Mediterranean Vineyard. Insects 2019, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, H.; Slingerland, K.; Ker, K.; Fisher, K.H.; Brewster, R. Reducing Cold Injury to Grapes Through the Use of Wind Ma-chines. 2020. Available online: https://traubenshow.de/images/stories/CCCC_2010/15_Hans_Peter_Pfeifer_Ontario_Canada/Presenttion/2010%20Jan%2011%20Final%20Wind%20Machine%20Report.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Bau, L.; Chassaing, T. Impact assessment of cover crops on the risk of frost in the Anjou vineyard. IVES_Viticulture 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crézé, C.M.; Horwath, W.R. Cover Cropping: A Malleable Solution for Sustainable Agriculture? Meta-Analysis of Ecosystem Service Frameworks in Perennial Systems. Agronomy 2021, 11, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergtold, J.; Sailus, M. (Eds.) Conservation Tillage Systems in the Southeast: Production, Profitability and Stewardship; SARE Handbook Series, 15; Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE): Beltsville, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, C.M.; Monteiro, A.; Rückert, F.E.; Gruber, B.; Steinberg, B.; Schultz, H.R. Transpiration of grapevines and co-habitating cover crop and weed species in a vineyard. A “snapshot” at diurnal trends. Vitis 2004, 43, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, A.; Lebon, E.; Voltz, M.; Wery, J. Relationships between plant and soil water status in vine (Vitis vinifera L.). Plant Soil 2004, 266, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.; Lopes, C.M. Influence of cover crop on water use and performance of vineyard in Mediterranean Portugal. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 121, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, H.F.; Valdes, G.S.B.; Lee, H.C. Mulch effects on rainfall interception, soil physical characteristics and temperature under Zea mays L. Soil Tillage Res. 2006, 91, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, J.M.; Monteiro, A.M.; Lopes, C.M.; Lourenco, J. Cover Crops in Vineyards of the Vinhos Verdes Region. A Three-Year Study of Variety Alvarinho. Cienc. Tec. Vitivinic. 2003, 18, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Homaee, M.; Afzalinia, S.; Ruhipour, H.; Basirat, S. Organic resource management: Impacts on soil aggregate stability and other soil physico-chemical properties. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 148, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, C.M.A.; Laureano, O.; Tomé, J.A. Culture et non culture de la vigne: Résultats de production, vigueur et composition des moûts, sur huit années d’essais. Ann. ANPP 1991, 3, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Agulhon, R. Intérêt des nouvelles techniques d’entretien des sols de vigne pour la viticulture, l’œnologie, l’environnement et la santé. Progrès Agric. Vitic. 1996, 113, 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- Geoffrion, R. L’enherbement permanent controlé des sols viticoles. Vingt ans de recherches sur le terrain en Anjou. Phytoma 2000, 530, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Böll, K.P. Versuche zur Gründüngung im Weinbau. Vitis 1967, 6, 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Griebel, T. Untersuchungen über die Anteile der Transpiration der Rebe und der Evaporation in begrünten Rebbeständen ander Gesamtverdunstung. Geisenheimer Berichte Band 1996, 28, 183. [Google Scholar]

- Prichard, T.L.; Sills, W.M.; Asai, W.K.; Hendricks, L.C.; Elmore, C.L. Orchard water use and soil characteri tics. Calif. Agric. 1989, 43, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Porquedduc, C.; Fiori, P.P.; Nueddus, S. Use of subterranean clover and burr medic as cover crop in vineyards. Option Mé-Diterranéennes 2000, 45, 445–448. [Google Scholar]

- Pou, A.; Gulías, J.; Moreno, M.; Tomás, M.; Medrano, H.; Cifre, J. Cover cropping in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Manto Negro vine-yards under Mediterranean conditions: Effects on plant vigour, yield and grape quality. OENO One 2011, 45, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoozlian, N.K.; Kliewer, W.M. Influence of Light on Grape Berry Growth and Composition Varies during Fruit Development. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1996, 121, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingels, C.A.; Scow, K.M.; Whisson, D.A.; Drenovsky, R.E. Effects of Cover Crops on Grapevines, Yield, Juice Composition, Soil Microbial Ecology, and Gopher Activity. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2005, 56, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Pérez, R.; Vicente-Díez, I.; Pou, A.; Pérez-Moreno, I.; Marco-Mancebón, V.S.; Campos-Herrera, R. Organic mulching modulated native populations of entomopathogenic nematode in vineyard soils differently depending on its potential to control outgrowth of their natural enemies. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2022, 192, 107781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergensen, R.G.; Mäder, P.; Fließbach, A. Long-term effects of organic farming on fungal and bacterial residues in relation to microbial energy metabolism. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2010, 46, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.B.; Araújo, A.S.F.; Leite, L.F.C.; Nunes, L.A.P.L.; Melo, W.J. Soil microbial biomass and organic matter fractions during transition from conventional to organic farming systems. Geoderma 2022, 170, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J.E.P. Actividad microbiológica y biomasa microbiana en suelos cafetaleros de los Andes venezolanos. Rev. Terra Latinoam. 2017, 36, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetunji, A.; Lewu, F.; Mulidzi, R.; Ncube, B. The biological activities of β-glucosidase, phosphatase and urease as soil quality indicators: A review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2017, 17, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Chang, W.; Qin, L. Beta-glucosidase activity in paddy soils of the taihu lake region, China. Pedosphere 2006, 16, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.; Agrawal, M.; Bohra, J.S. Effects of conventional tillage and no tillage permutations on extracellular soil enzyme activities and microbial biomass under rice cultivation. Soil Tillage Res. 2014, 136, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukumbareza, C.; Muchaonyerwa, P.; Chiduza, C. Bicultures of oat (Avena sativa L.) and grazing vetch (Vicia dasycarpa L.) cover crops increase contents of carbon pools and activities of selected enzymes in a loam soil under warm temperate conditions. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2016, 62, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Ali, E.; Afzal, K.B.; Osman, A.; Riaz, S. Soil Fertility: Factors Affecting Soil Fertility, and Biodiversity Responsible for Soil Fertility. Int. J. Plant Anim. Environ. Sci. 2022, 12, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, M.; Minervini, F.; De Angelis, M.; Papadia, P.; Migoni, D.; Dimaglie, M.; Dinu, D.G.; Quarta, C.; Selleri, F.; Caccioppola, A.; et al. Vineyard establishment under exacerbated summer stress: Effects of mycorrhization on rootstock agronomical parameters, leaf element composition and root-associated bacterial microbiota. Plant Soil 2022, 478, 613–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Kashyap, P.L.; Santoyo, G.; Newcombe, G. Plant Microbiome: Interactions, Mechanisms of Action, and Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 706049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darriaut, R.; Lailheugue, V.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I.; Marguerit, E.; Martins, G.; Compant, S.; Ballestra, P.; Upton, S.; Ollat, N.; Lauvergeat, V. Grapevine rootstock and soil microbiome interactions: Keys for a resilient viticulture. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, D.; Ding, J.; Xiao, X.; Liang, Y. Microbial coexistence in the rhizosphere and the promotion of plant stress resistance: A review. Environ. Res. 2023, 222, 115298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Walder, F.; Büchi, L.; Meyer, M.; Held, A.Y.; Gattinger, A.; Keller, T.; Charles, R.; A van der Heijden, M.G. Agricultural intensification reduces microbial network complexity and the abundance of keystone taxa in roots. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1722–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, P.; Rodríguez, I.; Fernández-Fernández, V.; Ramil, M.; Castrillo, D.; Acín-Albiac, M.; Adamo, I.; Fernán-dez-Trujillo, C.; García-Jiménez, B.; Acedo, A.; et al. Physicochemical properties and microbiome of vineyard soils from DOP Ribeiro (NW Spain) are in-fluenced by agricultural management. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, C.M.; Carter, K.R.; Carrell, A.A.; Jun, S.-R.; Jawdy, S.S.; Vélez, J.M.; Gunter, L.E.; Yang, Z.; Nookaew, I.; Engle, N.L.; et al. Abiotic Stresses Shift Belowground Populus-Associated Bacteria Toward a Core Stress Microbiome. mSystems 2018, 3, e00070-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, L.; Scavino, A.F. Strong shift in the diazotrophic endophytic bacterial community inhabiting rice (Oryza sativa) plants after flooding. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, fiv104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Stringlis, I.A.; Yu, K.; Feussner, K.; de Jonge, R.; Van Bentum, S.; Van Verk, M.C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Feussner, I.; Pieterse, C.M.J. MYB72-dependent coumarin exudation shapes root microbiome assembly to promote plant health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5213–E5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, J.H.; Kampouris, I.D.; Babin, D.; Sommermann, L.; Francioli, D.; Kuhl-Nagel, T.; Chowdhury, S.P.; Geistlinger, J.; Smalla, K.; Neumann, G.; et al. Beneficial microbial consortium improves winter rye performance by modulating bacterial communities in the rhizosphere and enhancing plant nutrient acquisition. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1232288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri, V.; Rossi, V.; Fedele, G. Efficacy of preharvest application of biocontrol agents against gray mold in grapevine. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1154370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarouchi, Z.; Esmaeel, Q.; Sanchez, L.; Jacquard, C.; Hafidi, M.; Vaillant-Gaveau, N.; Ait Barka, E. Beneficial microor-ganisms to control the gray mold of grapevine: From screening to mechanisms. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, G.; Brischetto, C.; Rossi, V. Biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea on Grape Berries as Influenced by Temperature and Humidity. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannerucci, F.; D’Ambrosio, G.; Regina, N.; Schiavone, D.; Bruno, G.L. New potential biological limiters of the main esca-associated fungi in grapevine. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Verma, J.P. Does plant—Microbe interaction confer stress tolerance in plants: A review? Microbiol. Res. 2018, 207, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.V.; Srivastava, S.; Singh, N.; Behl, H.M. Role of metal resistant plant growth promoting bacteria in ameliorat-ing fly ash to the growth of Brassica juncea. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 170, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- São-José, C.; Santos, M.A.; Schmitt, M.J. Viruses of wine-associated yeasts and bacteria. In Biology of Microorganisms on Grapes, in Must and in Wine; König, H., Unden, G., Fröhlich, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Garrido, C.; Roudet, J.; Aveline, N.; Davidou, L.; Dupin, S.; Fermaud, M. Microbial Antagonism Toward Botrytis Bunch Rot of Grapes in Multiple Field Tests Using One Bacillus ginsengihumi Strain and Formulated Biological Control Products. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, F.T.; Griffiths, R.I.; Knight, C.G.; Nicolitch, O.; Williams, A. Harnessing rhizosphere microbiomes for drought-resilient crop production. Science 2020, 368, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Medellín, C.; Edwards, J.; Liechty, Z.; Nguyen, B.; Sundaresan, V. Drought Stress Results in a Compartment-Specific Restructuring of the Rice Root-Associated Microbiomes. mBio 2017, 8, e00764-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogales, A.; Rottier, E.; Campos, C.; Victorino, G.; Costa, J.M.; Coito, J.L.; Pereira, H.S.; Viegas, W.; Lopes, C. The effects of field inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi through rye donor plants on grapevine performance and soil properties. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 313, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daler, S.; Uygun, E. Effects of Putrescine Application Against Drought Stress on the Morphological and Physiological Charac-teristics of Grapevines. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Mazahar, S.; Chapadgaonkar, S.S.; Giri, P.; Shourie, A. Phyto-microbiome to mitigate abiotic stress in crop plants. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1210890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, V.; Solomon, S.; Mall, A.K.; Prajapati, C.P.; Hashem, A.; Allah, E.F.A.; Ansari, M.I. Morphological assessment of water stressed sugarcane: A comparison of waterlogged and drought affected crop. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, S.; Naqqash, T.; Nawaz, M.S.; Laraib, I.; Siddique, M.J.; Zia, R.; Mirza, M.S.; Imran, A. Rhizosphere Engineering with Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms for Agriculture and Ecological Sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 617157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M.; Deka, S. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria—Alleviators of abiotic stresses in soil: A review. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Song, L.; Xiao, Y.; Ge, W. Drought-Tolerant Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Associated with Foxtail Millet in a Semi-arid Agroecosystem and Their Potential in Alleviating Drought Stress. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyas, N.; Mumtaz, K.; Akhtar, N.; Yasmin, H.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Khan, W.; Enshasy, H.A.E.; Dailin, D.J.; Elsayed, E.A.; Ali, Z. Exopolysaccha-rides producing bacteria for the amelioration of drought stress in wheat. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, D.; Pande, V.; Pandey, S.C.; Samant, M. Recent advances in PGPR and molecular mechanisms involved in drought stress resistance. J Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kálmán, C.D.; Nagy, Z.; Berényi, A.; Kiss, E.; Posta, K. Investigating PGPR bacteria for their competence to protect hybrid maize from the factor drought stress. Cereal Res. Commun. 2024, 52, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Reith, F.; Dennis, P.G.; Hamonts, K.; Powell, J.R.; Young, A.; Singh, B.K.; Bissett, A. Ecological drivers of soil microbial diversity and soil biological networks in the Southern Hemisphere. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoglan, M.; Radić, T.; Anić, M.; Andabaka, Ž.; Stupić, D.; Tomaz, I.; Mesić, J.; Karažija, T.; Petek, M.; Lazarević, B.; et al. Mycorrhizal Fungi Enhance Yield and Berry Chemical Composition of in Field Grown “Cabernet Sauvignon” Grapevines (V. vinifera L.). Agriculture 2021, 11, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolás, E.; Maestre-Valero, J.F.; Alarcón, J.J.; Pedrero, F.; Vicente-Sánchez, J.; Bernabé, A.; Gómez-Montiel, J.; Hernández, J.A.; Fernández, F. Effectiveness and persistence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the physiology, nutrient uptake and yield of Crimson seedless grapevine. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vineyard Management Practices | Impact on SOC | Impact on Soil and Water Health | Impact on Vine Productivity/Yield | Other Details/Benefits/ Disadvantages | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Tillage | SOC losses,  decomposition of organic matter. decomposition of organic matter. 52.1% SOC  with the conversion of fields to vineyards. with the conversion of fields to vineyards. |  rates of soil erosion, destruction of fungal hyphae and soil fauna habitats rates of soil erosion, destruction of fungal hyphae and soil fauna habitats |  short-term performance short-term performance | Conventionally emits of 15.4 to 17.41 Mg CO2 eq ha−1 year−1- | Ruiz-Comenero et al. [32]; Coll et al. [33]; Eldon and Gershenson [34]; Nistor et al. [35]. |

| No Tillage |  SOC. Sequestration rate of 3.50 Mg CO2-eq. ha−1 year−1. Helps preserve soil aggregates. SOC. Sequestration rate of 3.50 Mg CO2-eq. ha−1 year−1. Helps preserve soil aggregates. |  soil erosion, soil erosion,  soil structure, and soil moisture. soil structure, and soil moisture.  soil respiration. Minimal soil disturbance soil respiration. Minimal soil disturbance |  Yield Yield |  soil carbon. soil carbon.  SOC at greater depths. SOC at greater depths. | Eldon and Gershenson [34]; Payen et al. [29]; Visconti et al. [36]. |

| Cover Crops |  GHG (Greenhouse gas emissions), GHG (Greenhouse gas emissions),  soil fertility/carbon/ SOC (4.45 Mg CO2-eq. ha−1 year−1). soil fertility/carbon/ SOC (4.45 Mg CO2-eq. ha−1 year−1).  carbon by 1.4 times in 5 years, carbon by 1.4 times in 5 years, |  water infiltration rates/soil aggregation/water-holding capacity/arthropod biodiversity/microbial activity water infiltration rates/soil aggregation/water-holding capacity/arthropod biodiversity/microbial activity reduce soil erosion. reduce soil erosion. copper phytoremediation |  yield (22–85%) for competition. yield (22–85%) for competition. |  soil surface slow down the decomposition of organic matter, soil surface slow down the decomposition of organic matter,  accumulation of SOC accumulation of SOC | Petersen et al. [37]; Burgio et al. [38]; Nistor et al. [35]; Payen et al. [29]; Visconti et al. [36]. |

| Pruning Residues |  increases SOC. increases SOC. |  microbial activity/fertility/water infiltration/retention microbial activity/fertility/water infiltration/retention erosion/ nutrient loss erosion/ nutrient loss optimizing water efficiency. |  to crush it and incorporate it into the soil carbon sequestration. to crush it and incorporate it into the soil carbon sequestration. | Eldona and Gershensonb [34]. | |

| Organic Amendments |  SOC by +44%/ SOC by +44%/Compost and herbaceous mulch. |  soil fertility and microbial activity/SOC content. soil fertility and microbial activity/SOC content. | Morlat and Chaussod [39]; Genesio et al. [40]; García-Orenes et al. [41]; Gaiotti et al. [42]; Torres et al. [43]. | ||

| Biochar |  SOC (18%) SOC (18%) | =Soil function (Dosage 100 t/ha or more). |  productivity/grape quality. productivity/grape quality. | Most studies are short-term (≤5 years); a long-term evaluation is required. | Paustian et al. [5]. |

| Cover Type | General Advantages | Species | Particular Advantage | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legumes | Increases N total and mineral and YAN. Higher N in plant tissues, They produce aerial mass with lower C:N than rye | Phacelia tanacetifolia | Increases soil moisture and vigor. Attracts beneficial insects. Improves soil health. | Fernando et al. [69]; Feng et al. [72]. |

| Medicago L. | Loss of yield compared to herbicide control. Self-seeding annuals that are suitable for areas with less than 700 mm of annual rainfall. | Lines et al. [73]. | ||

| Vicia Sativa | Competes with other species | Nicholas et al. [74]. | ||

| Lotus corniculata | Can improve the physical structure of the soil by decreasing the bulk density and preventing compaction. | Capri et al. [68]. | ||

| Trifolium | It adapts to semi-arid conditions with irrigation, controlling weeds effectively. Effective cover crop under the vine in irrigated vineyards, controlling weeds well, with low establishment costs (it is perennial) and providing nitrogen. Multi-cut varieties resprout vigorously after mowing. | Nicholas et al. [74]; Abad et al. [75]. | ||

| Grasses | It improves soil structure and controls erosion. It prevents leaching. It increases water infiltration, improving soil profile filling in winter. Grapevines are more temperature-resistant than indoor plants, allowing them to grow in the fall after the plant stops growing and before it begins to bud in spring. | Secale cereale | Rye can produce a dense cover that is very competitive with weeds. C:N high. Preferred in low rainfall situations. Tolerates dry and poor soils. Tolerates a wide pH range and dry, infertile and sandy soils | Leonard and Andeieux [76]; Nicholas et al. [74]; Kolb et al. [77]; Novara et al. [70]. |

| Festuca spp. | Competing for water. Suitable as a permanent cover between rows (dwarf). Festuca ovina has been noted for having the lowest evapotranspiration (ET) rates among grasses, making it suitable for permanent inter-row cover. Tall fescue can be quite competitive, and complete ground cover with it can reduce yields. | Celette et al. [78]; Capri et al. [68]. | ||

| Lolium | They are very competitive and fast growing with an extensive fibrous root system. | Nandula, [79]. | ||

| Hordeum vulgare | It establishes quickly and can produce a dense cover that is very competitive with weeds, useful for erosion control. | Zumkeller et al. [16] | ||

| Dactylis glomerata | Can compete excessively with vines. Moderately persistent perennial that tolerates infertile and acidic soils, but not waterlogging. | Nicholas et al. [74]; Abad et al. [75]. | ||

| Native species (e.g., Wallaby grass, Phacelia, Atriplex semibaccata) | They present local adaptation, improve biodiversity, do not impact yield, and in normal years do not require water supplementation. Native species are often the most competitive for both water and nutrients if not managed properly. | Rytidosperma geniculatum | Perennial grass native to Australia, well adapted to low humidity and nutrient conditions, without aggressively competing with vines. | Lines et al. [73]. |

| Phacelia tanacetifolia | Improve vine vigor | Ball et al. [80]; Fernando et al. [69] | ||

| Paspalum vaginatum | Increased the frequency of earthworms | Lines et al. [73]. | ||

| Atriplex semibaccata | It works very well as a cover crop in hot, dry environments with high biomass production and weed suppression. | Penfold and Collins [81]. | ||

| Portulaca oleracea | It reduced photosynthetically active radiation and temperature in the fruiting zone. It resulted in lower total soluble solids (TSS) content in the grapes, higher titratable acidity (TA), lower alcohol content in the wine, and higher TA in the wine. It increased the anthocyanin and flavonol content of the grapes and wines, and improved the wines’ sensory value, especially floral aroma and complexity. | Peng et al. [82]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deis, L.; Fort, F.; Lin-Yang, Q.; Balda, P.; Pou, A. Carbon Sequestration, Plant Cover, and Soil Health: Strategies to Mitigate Climate Change. Plants 2025, 14, 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233610

Deis L, Fort F, Lin-Yang Q, Balda P, Pou A. Carbon Sequestration, Plant Cover, and Soil Health: Strategies to Mitigate Climate Change. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233610

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeis, Leonor, Francesca Fort, Qiying Lin-Yang, Pedro Balda, and Alicia Pou. 2025. "Carbon Sequestration, Plant Cover, and Soil Health: Strategies to Mitigate Climate Change" Plants 14, no. 23: 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233610

APA StyleDeis, L., Fort, F., Lin-Yang, Q., Balda, P., & Pou, A. (2025). Carbon Sequestration, Plant Cover, and Soil Health: Strategies to Mitigate Climate Change. Plants, 14(23), 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233610