Research on Utilizing Phosphorus Tailing Recycling to Improve Acidic Soil: The Synergistic Effect on Crop Yield, Soil Quality, and Microbial Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

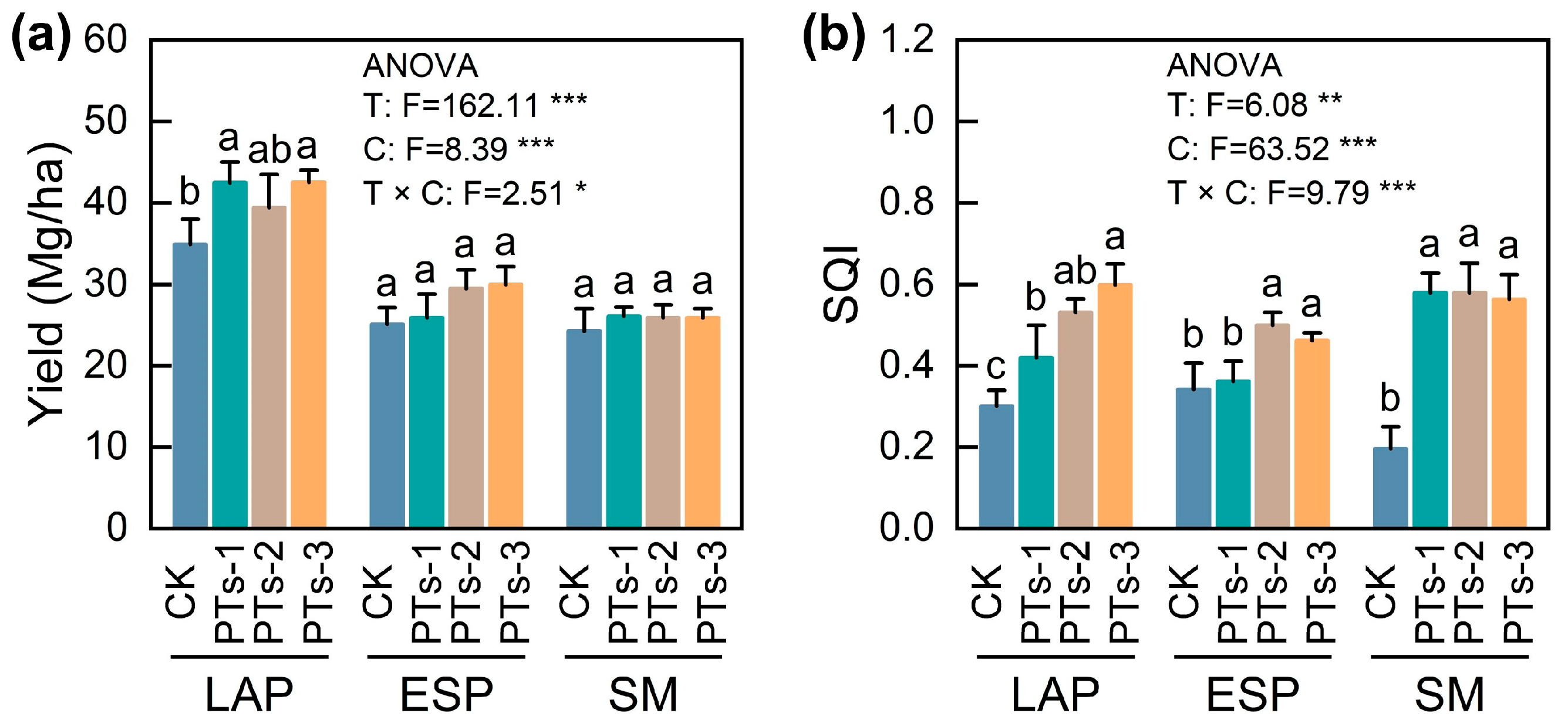

2.1. Crop Yield and Soil Quality

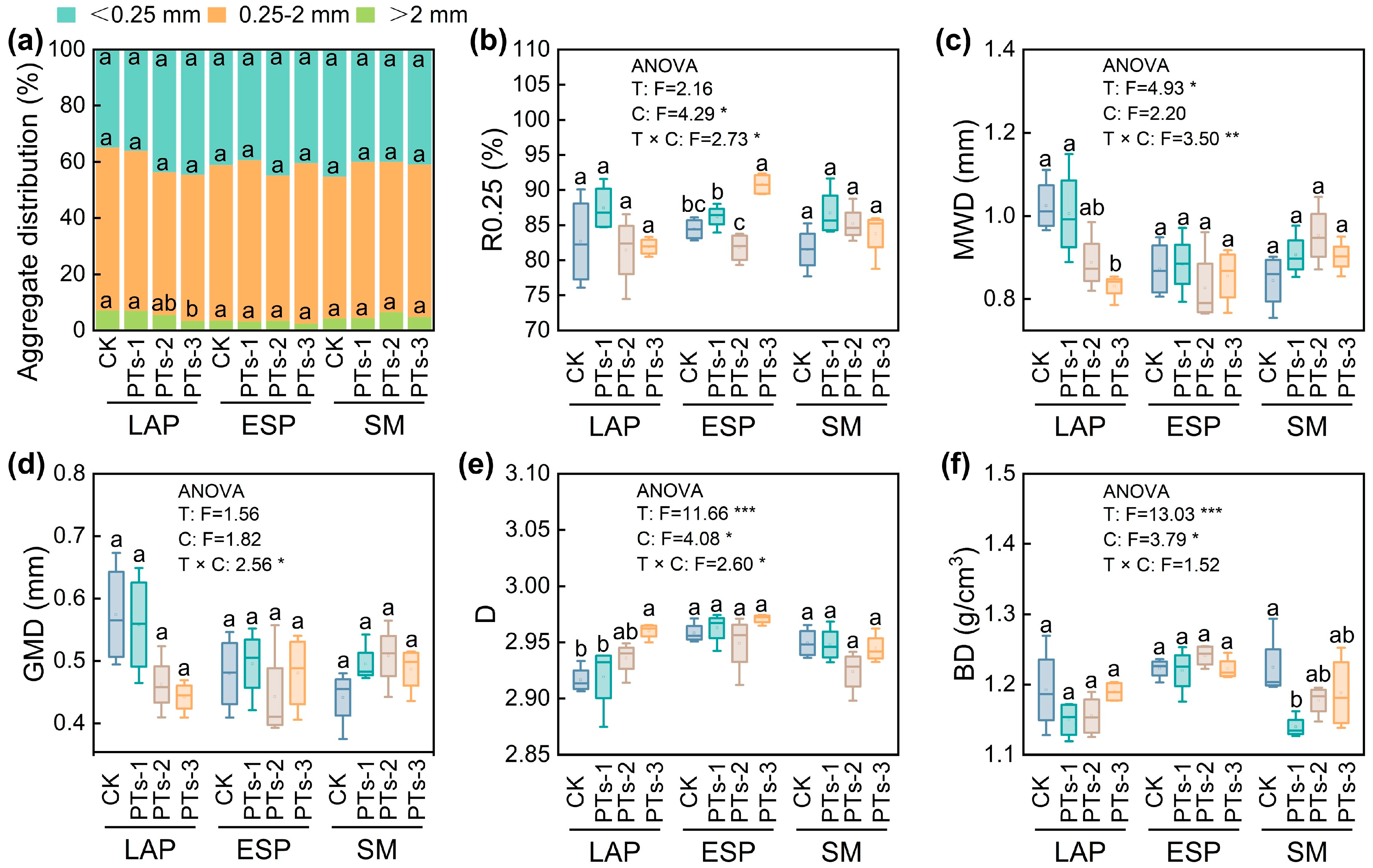

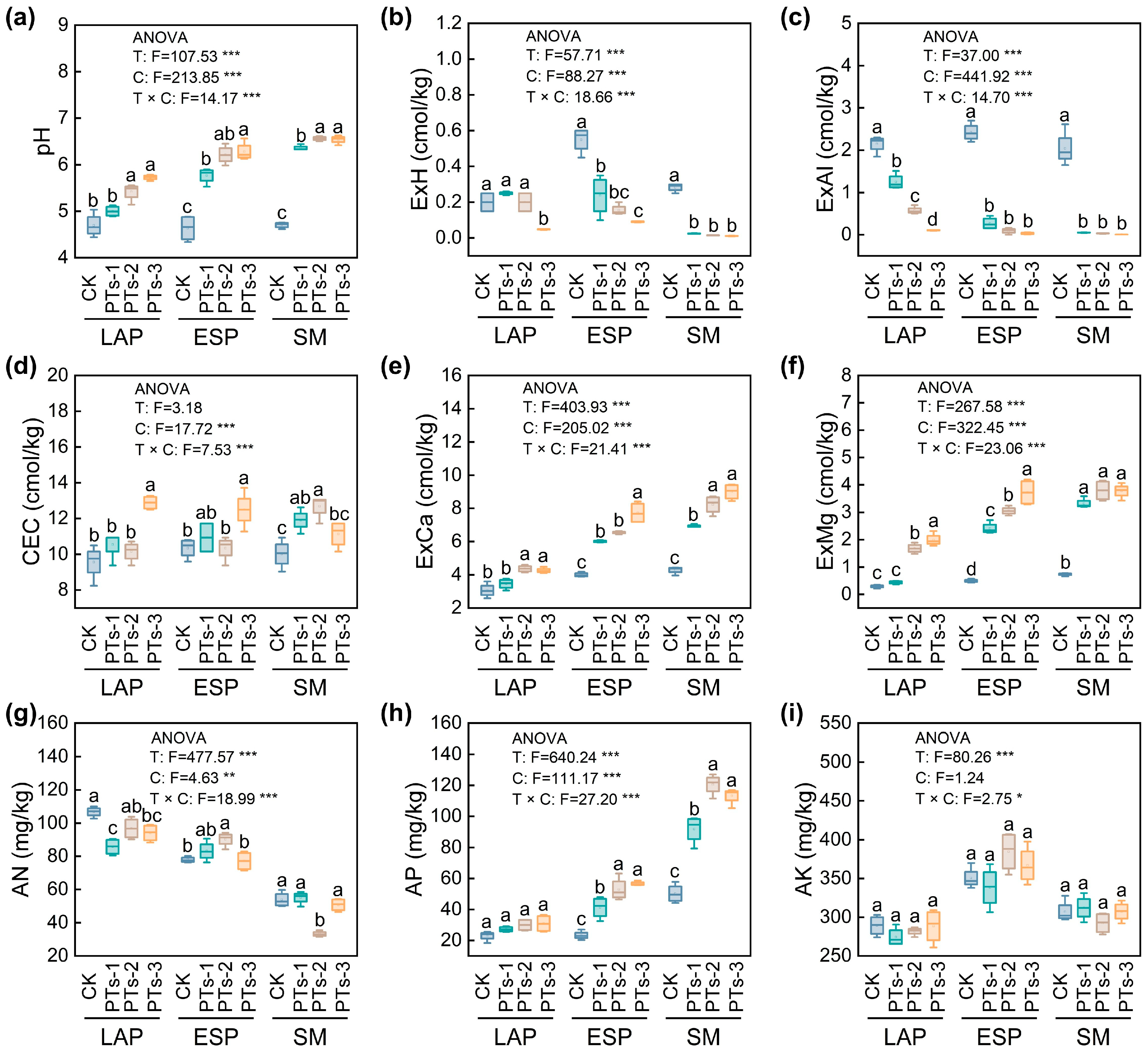

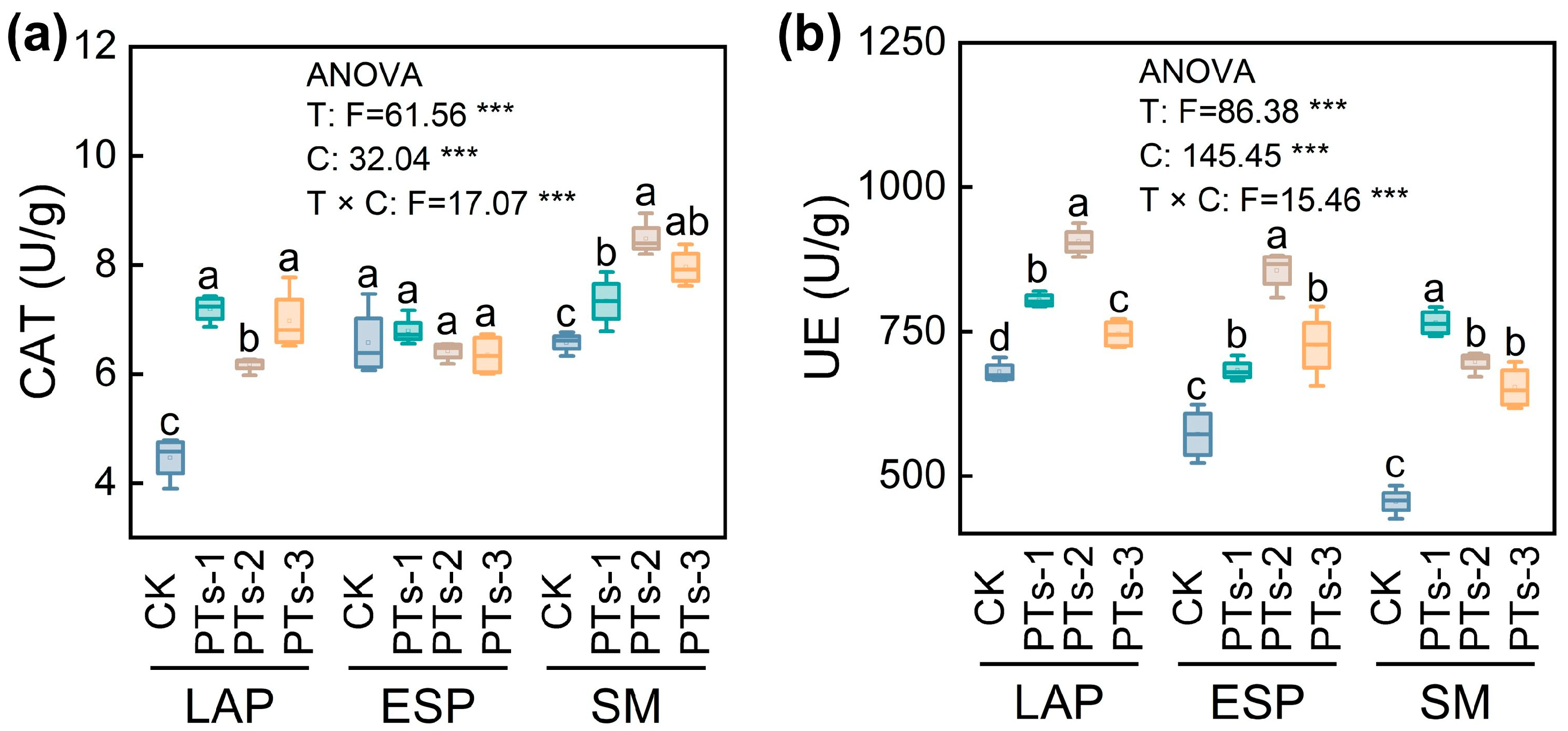

2.2. Physical, Chemical, and Biological Characteristics of the Soil

2.3. Diversity, Composition, and Key Groups of the Bacterial and Fungal Communities in the Soil

2.4. Correlation Analysis Between the Soil Quality, Crop Yield, and Soil Properties

2.5. Determinants of Crop Yield

3. Discussion

3.1. The Effect of PTs on the Soil Properties

3.2. Bacterial and Fungal Response to the PTs During Acidic Soil Remediation

3.3. The Impact of Soil Properties and Soil Quality on Crop Yield

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Overview of the Experimental Site

4.2. Test Design and Sample Collection

4.3. Analysis of the Soil Sample Properties

4.4. 16S rDNA and ITS rDNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

4.5. Characteristic Hydrolytic Stability Index and Soil Quality Index (SQI) Analysis

4.5.1. Calculation of the Characteristic Soil Water Aggregate Stability Index

4.5.2. SQI Calculation

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teutscherova, N.; Vazquez, E.; Masaguer, A.; Navas, M.; Scow, K.M.; Schmidt, R.; Benito, M. Comparison of Lime- and Biochar-Mediated PH Changes in Nitrification and Ammonia Oxidizers in Degraded Acid Soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2017, 53, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant Acidification in Major Chinese Croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Mao, Q.; Gilliam, F.S.; Luo, Y.; Mo, J. Nitrogen Deposition Contributes to Soil Acidification in Tropical Ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 20, 3790–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, J.L.; Zhang, H.; Girma, K.; Raun, W.R.; Penn, C.J.; Payton, M.E. Soil Acidification from Long-Term Use of Nitrogen Fertilizers on Winter Wheat. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xia, F.; Liu, X.; He, Y.; Xu, J.; Brookes, P.C. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilizer on the Acidification of Two Typical Acid Soils in South China. J. Soils Sediments 2013, 14, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdicek, D. Subsoil Ridge Tillage and Lime Effects on Soil Microbial Activity, Soil PH, Erosion, and Wheat and Pea Yield in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Soil Tillage Res. 2003, 74, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, T.G.; Mallawaarachchi, T.; Pringle, M.J.; Menzies, N.W.; Dalal, R.C.; Kopittke, P.M.; Searle, R.; Hochman, Z.; Dang, Y.P. Quantifying the Economic Impact of Soil Constraints on Australian Agriculture: A Case-Study of Wheat. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 3866–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijbeek, R.; van Loon, M.P.; Ouaret, W.; Boekelo, B.; van Ittersum, M.K. Liming Agricultural Soils in Western Kenya: Can Long-Term Economic and Environmental Benefits Pay off Short Term Investments? Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwiringiyimana, E.; Lai, H.; Ni, N.; Shi, R.; Pan, X.; Gao, J.; Biswash, M.R.; Li, J.; Cui, X.; Xu, R. Comparative Efficacy of Alkaline Slag, Biomass Ash, and Biochar Application for the Amelioration of Different Acidic Soils. Plant Soil 2024, 504, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lollato, R.P.; Edwards, J.T.; Zhang, H. Effect of Alternative Soil Acidity Amelioration Strategies on Soil PH Distribution and Wheat Agronomic Response. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2013, 77, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Sarmah, A.K.; Bordoloi, S.; Bolan, S.; Padhye, L.P.; Van Zwieten, L.; Sooriyakumar, P.; Khan, B.A.; Ahmad, M.; Solaiman, Z.M.; et al. Soil Acidification and the Liming Potential of Biochar. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Shen, C.; Zou, Z.; Fu, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Han, W.; Fan, L. Biochar Stimulates Tea Growth by Improving Nutrients in Acidic Soil. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 283, 110078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Xu, R.; Nkoh, J.N.; Lu, H.; Hua, H.; Guan, P. Effects of Straw Decayed Products of Four Crops on the Amelioration of Soil Acidity and Maize Growth in Two Acidic Ultisols. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 5092–5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Li, B.; Vogt, R.D.; Mulder, J.; Song, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, J. Straw Return Exacerbates Soil Acidification in Major Chinese Croplands. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafasfeh, A.; Khodakarami, M.; Alagha, L.; Moats, M.; Molatlhegi, O. Selective Depression of Silicates in Phosphate Flotation Using Polyacrylamide-Grafted Nanoparticles. Miner. Eng. 2018, 127, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, S.; Gaxiola, R.; Schilling, R.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; López-Arredondo, D.; Wissuwa, M.; Delhaize, E.; Rouached, H. Improving Phosphorus Use Efficiency: A Complex Trait with Emerging Opportunities. Plant J. 2017, 90, 868–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, D.; Wu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Z. A New Enrichment Method of Medium–Low Grade Phosphate Ore with High Silicon Content. Miner. Eng. 2022, 181, 107548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.-H.; E, S.-Z.; Che, Z.-X. The Ameliorative Effects of Low-Grade Palygorskite on Acidic Soil. Soil Res. 2020, 58, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozsin, G.; Arol, A.I.; Cayci, G. Evaluation of Pyritic Tailings from a Copper Concentration Plant for Calcareous Sodic Soil Reclamation. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2014, 50, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.V. Plant Growth in Response to Phosphorus Fertilizers in Acidic Soil Amended with Limestone or Organic Matter. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2012, 43, 1800–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venäläinen, S.H.; Nousiainen, A.; Kanerva, S. The Potential of Phosphate Mine Tailings in the Remediation of Acidic Pb-Contaminated Soil. Soil Environ. Health 2024, 2, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venäläinen, S.H.; Nousiainen, A.; Silvennoinen, M.; Kanerva, S. Stabilization of as and Sb in Contaminated Acidic Shooting Range Soil with Apatite Mine Tailings: Challenge of Co-Contamination. Soil Environ. Health 2024, 3, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, D.; Carrión, V.J.; Revillini, D.; Yin, S.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Acidification Suppresses the Natural Capacity of Soil Microbiome to Fight Pathogenic Fusarium Infections. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Naresh, R.K.; Kumar, Y.; Yadav, R.B. Conservation Tillage and Fertilization Impact on Carbon Sequestration and Mineralization in Soil Aggregates in the North West IGP under an Irrigated Rice-Wheat Rotation: A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Ni, S.; Wang, J.; Cai, C. Aggregate Pore Structure, Stability Characteristics, and Biochemical Properties Induced by Different Cultivation Durations in the Mollisol Region of Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 233, 105797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Ma, D.; Chen, L.; Zhou, G.; Duan, Y.; Tao, L.; Chen, J. Relationship Between Calcium Forms and Organic Carbon Content in Aggregates of Calcareous Soils in Northern China. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 244, 106210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C. Chapter 7 Ameliorating Soil Acidity of Tropical Oxisols by Liming for Sustainable Crop Production. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0065211308004070 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Zhang, P.; Chen, X.; Wei, T.; Yang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Yang, B.; Han, Q.; Ren, X. Effects of Straw Incorporation on the Soil Nutrient Contents, Enzyme Activities, and Crop Yield in a Semiarid Region of China. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 160, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.E.; Bennett, A.E.; Newton, A.C.; White, P.J.; McKenzie, B.M.; George, T.S.; Pakeman, R.J.; Bailey, J.S.; Fornara, D.A.; Hayes, R.C. Liming Impacts on Soils, Crops and Biodiversity in the UK: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.; Cai, A.; Liu, K.; Huang, J.; Wang, B.; Li, D.; Qaswar, M.; Feng, G.; Zhang, H. The Links Between Potassium Availability and Soil Exchangeable Calcium, Magnesium, and Aluminum Are Mediated by Lime in Acidic Soil. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 19, 1382–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.L.; Luo, J.N. Potassium-Release Mechanism on Drying Soils. Soil Sci. 1986, 141, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Ge, F.; Zhang, D.; Deng, S.; Liu, X. Roles of Phosphate Solubilizing Microorganisms from Managing Soil Phosphorus Deficiency to Mediating Biogeochemical P Cycle. Biology 2021, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Jiang, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, P.; Yao, Y.; Chen, X. Heavy Metal Content and Microbial Characteristics of Soil Plant System in Dabaoshan Mining Area, Guangdong Province. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramut, R.; Jama-Rodzeńska, A.; Woźniak, M.; Siebielec, S.; Kamińska, J.; Szuba-Trznadel, A.; Gałka, B. The Effect of Broadcast Struvite Fertilization on Element Soil Content and Microbial Activity Changes in Winter Wheat Cultivation in Southwest Poland. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, R.; Fu, W.; Fu, X. Phosphorus Dynamics in Volcanic Soils of Weizhou Island, China: Implications for Environmental and Agricultural Applications. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, C.; Liang, G.; Sun, J.; He, P.; Tang, S.; Yang, S.; Zhou, W.; Wang, X. The Alleviation of Acid Soil Stress in Rice by Inorganic or Organic Ameliorants Is Associated with Changes in Soil Enzyme Activity and Microbial Community Composition. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2015, 51, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, X.; Chen, M.; Lou, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, Q.; Pan, H.; Zhuge, Y. Effects of Soil Acidification on Bacterial and Fungal Communities in the Jiaodong Peninsula, Northern China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, L.X.; Jie, X.; Hu, D.; Feng, B.; Yue, K.; et al. Rare Fungus, Mortierella Capitata, Promotes Crop Growth by Stimulating Primary Metabolisms Related Genes and Reshaping Rhizosphere Bacterial Community. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 108017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, A.; Liu, J.; Zou, S.; Rensing, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xing, S.; Yang, W. Enhancement of Cadmium Uptake in Sedum Alfredii Through Interactions Between Salicylic Acid/Jasmonic Acid and Rhizosphere Microbial Communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Peñuelas, J.; Chu, H. Abundance of Kinless Hubs Within Soil Microbial Networks Are Associated with High Functional Potential in Agricultural Ecosystems. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lei, S.; Wu, H.; Liao, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, G.; Fang, L.; Song, Z. Simplified Microbial Network Reduced Microbial Structure Stability and Soil Functionality in Alpine Grassland along a Natural Aridity Gradient. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 191, 109366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, L.; Feng, Q.; Luo, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, C.; Cao, X.; Li, N. Influence and Role of Fungi, Bacteria, and Mixed Microbial Populations on Phosphorus Acquisition in Plants. Agriculture 2024, 14, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, N.; Deng, X.; Thomashow, L.S.; Lidbury, I.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Shen, Q.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Phosphorus Availability Influences Disease-Suppressive Soil Microbiome Through Plant-Microbe Interactions. Microbiome 2024, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.S.A.; Crusciol, C.A.C. Effects of Superficial Liming and Silicate Application on Soil Fertility and Crop Yield under Rotation. Geoderma 2013, 195–196, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshiabukole, J.P.K.; Khonde, G.P.; Phongo, A.M.; Ngoma, N.; Vumilia, R.K.; Kankolongo, A.M. Liming and Mineral Fertilization of Acid Soils in Maize Crop Within the Savannah of Southwestern of Democratic Republic of Congo. OALib 2022, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Cai, Z.; Xu, Z. Does Ammonium-Based N Addition Influence Nitrification and Acidification in Humid Subtropical Soils of China? Plant Soil 2007, 297, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahman, S.; Han, J.-C.; Ahmad, M.; Ashraf, M.N.; Khaliq, M.A.; Yousaf, M.; Wang, Y.; Yasin, G.; Nawaz, M.F.; Khan, K.A.; et al. Aluminum Phytotoxicity in Acidic Environments: A Comprehensive Review of Plant Tolerance and Adaptation Strategies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 269, 115791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Tahvanainen, T.; Malard, L.; Chen, L.; Pérez-Pérez, J.; Berninger, F. Global Analysis of Soil Bacterial Genera and Diversity in Response to PH. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 198, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; He, Z.; Lu, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, J.; Qiu, S.; Ge, S. Response of Nitrifiers to Gradually Increasing PH Conditions in a Membrane Nitrification Bioreactor: Microbial Dynamics and Alkali-Resistant Mechanism. Water Res. 2024, 268, 122567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, E.M.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil Aggregate Isolation Method Affects Measures of Intra-Aggregate Extracellular Enzyme Activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 69, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.; Fang, L.; Shen, G.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Chen, J.; Zhou, G.; Ma, D.; Bing, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; et al. New Perspectives on Microbiome and Nutrient Sequestration in Soil Aggregates during Long-Term Grazing Exclusion. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 30, e17027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S. Analysis of Agrochemical Soil; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Ma, W.; Chen, S.; Jiang, Q.; He, K.; Shi, Z. Assessment of Important Soil Properties Related to Chinese Soil Taxonomy Based on Vis–NIR Reflectance Spectroscopy. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 144, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruneh, G.A.; Hanjagi, A.; Phaneendra, B.; Lalitha, M.; Vasundhara, R.; Ramamurty, V.; Abdul Rahaman, S.; Ravikiran, T.; Simegn, A.A.; Addis, T.M.; et al. Pedogenic Variables with Color Indices of Rubified Alfisols in the Kakalachinte Microwatershed, Karnataka, South India. Geoderma Reg. 2024, 38, e00839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-L.; Gong, Z.-T. Soil Survery Laboratory Methods; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liang, C.; Luo, Y.; Xu, Q.; Han, C.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, B. Correction to: Competitive Interaction with Keystone Taxa Induced Negative Priming under Biochar Amendments. Microbiome 2019, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Jing, M.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Jiang, J.; et al. Long-Term Effect of Epigenetic Modification in Plant–Microbe Interactions: Modification of DNA Methylation Induced by Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria Mediates Promotion Process. Microbiome 2022, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Jiang, Y.-H.; Yang, Y.; He, Z.; Luo, F.; Zhou, J. Molecular Ecological Network Analyses. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, B.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; Chen, L.; Zhou, S. Aggregate-Related Changes in Network Patterns of Nematodes and Ammonia Oxidizers in an Acidic Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 88, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wen, S.; Wei, S.; Li, H.; Feng, Y.; Ren, G.; Yang, G.; Han, X.; Wang, X.; Ren, C. Straw Incorporation plus Biochar Addition Improved the Soil Quality Index Focused on Enhancing Crop Yield and Alleviating Global Warming Potential. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanalle, R.M.; Ganga, G.M.D.; Godinho Filho, M.; Lucato, W.C. Green Supply Chain Management: An Investigation of Pressures, Practices, and Performance Within the Brazilian Automotive Supply Chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Type | Organic Matter (g·kg−1) | AN (mg·kg−1) | AP (mg·kg−1) | AK (mg·kg−1) | pH | EA (cmol·kg−1) | ExK (cmol·kg−1) | ExNa (cmol·kg−1) | ExCa (cmol·kg−1) | ExMg (cmol·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upland Red Soil | 26.67 | 145.25 | 24.44 | 309.50 | 4.67 | 3.31 | 1.12 | 0.72 | 3.06 | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geng, C.; Shi, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Yang, J.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Fan, W. Research on Utilizing Phosphorus Tailing Recycling to Improve Acidic Soil: The Synergistic Effect on Crop Yield, Soil Quality, and Microbial Communities. Plants 2025, 14, 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223475

Geng C, Shi H, Wang J, Zhang H, Ma X, Yang J, Sun X, Li Y, Zheng Y, Fan W. Research on Utilizing Phosphorus Tailing Recycling to Improve Acidic Soil: The Synergistic Effect on Crop Yield, Soil Quality, and Microbial Communities. Plants. 2025; 14(22):3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223475

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeng, Chuanxiong, Huineng Shi, Jinghui Wang, Huimin Zhang, Xinling Ma, Jinghua Yang, Xi Sun, Yupin Li, Yi Zheng, and Wei Fan. 2025. "Research on Utilizing Phosphorus Tailing Recycling to Improve Acidic Soil: The Synergistic Effect on Crop Yield, Soil Quality, and Microbial Communities" Plants 14, no. 22: 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223475

APA StyleGeng, C., Shi, H., Wang, J., Zhang, H., Ma, X., Yang, J., Sun, X., Li, Y., Zheng, Y., & Fan, W. (2025). Research on Utilizing Phosphorus Tailing Recycling to Improve Acidic Soil: The Synergistic Effect on Crop Yield, Soil Quality, and Microbial Communities. Plants, 14(22), 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223475