Water–Nitrogen Coupling Under Film Mulching Synergistically Enhances Soil Quality and Winter Wheat Yield by Restructuring Soil Microbial Co-Occurrence Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sample Collection and Measurements

2.3.1. Soil Sample Collection

2.3.2. Soil Physicochemical Property Determination

2.3.3. Collection and Determination of Winter Wheat Plant Samples

2.3.4. DNA Extraction and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.4. Soil Quality Index and Water and Nitrogen Use Efficiency of Winter Wheat

2.4.1. Winter Wheat Harvest Index and Water and Nitrogen Use Efficiency

- (1)

- Irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE, kg·m−3) [39]

- (2)

- Agronomic efficiency of nitrogen (AEN, kg·kg−1) [40]

- (3)

- Harvest index (HI) [41]

2.4.2. Soil Quality Evaluation

2.4.3. Calculation of the Co-Occurrence Network

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of Winter Wheat Soils

3.2. Soil Microbial Community and Network Co-Occurrence of Winter Wheat

3.2.1. Microbial Diversity of Winter Wheat

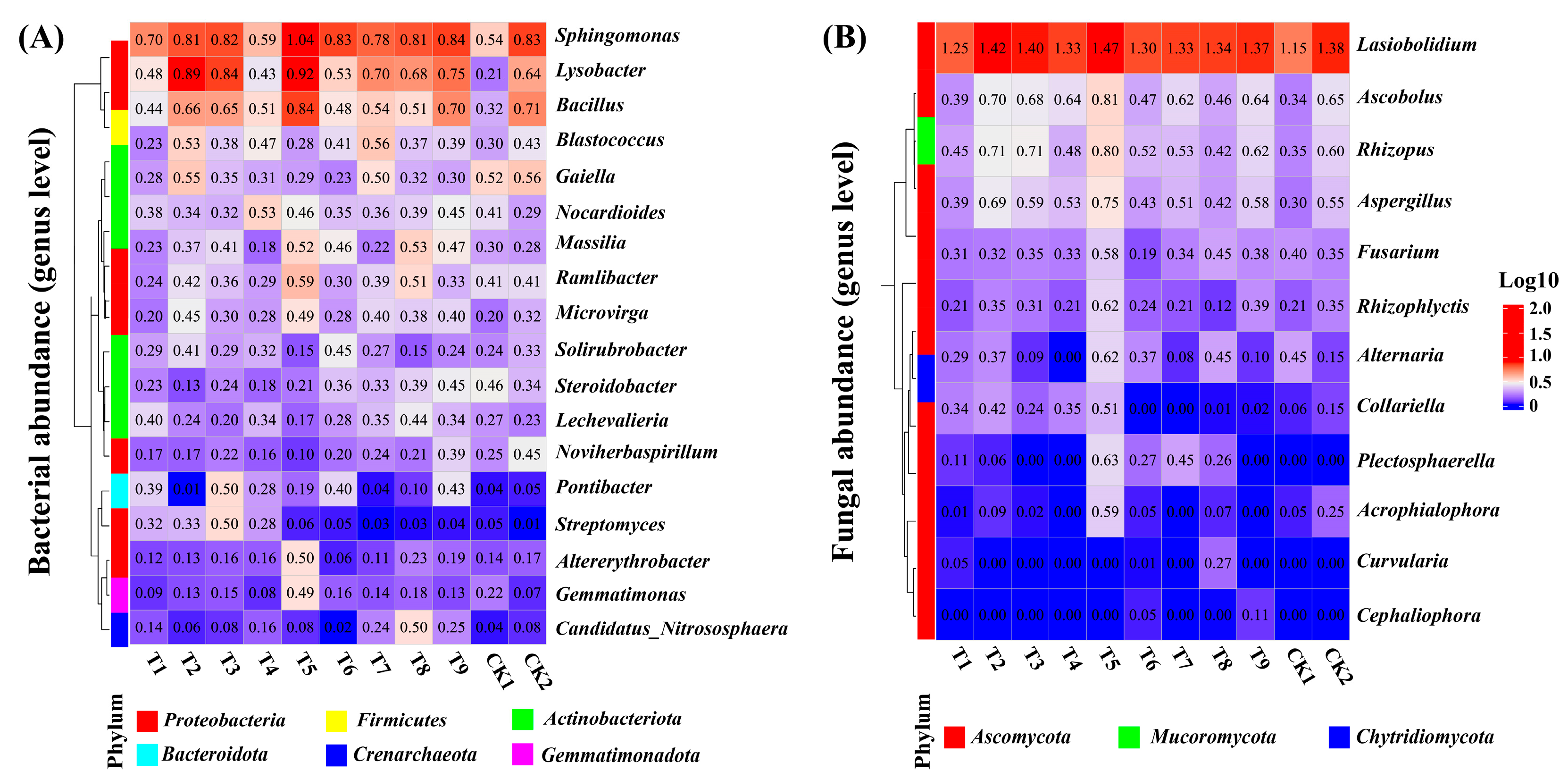

3.2.2. Microbial Community of Winter Wheat

3.2.3. Soil Microbial Co-Occurrence Networks of Winter Wheat

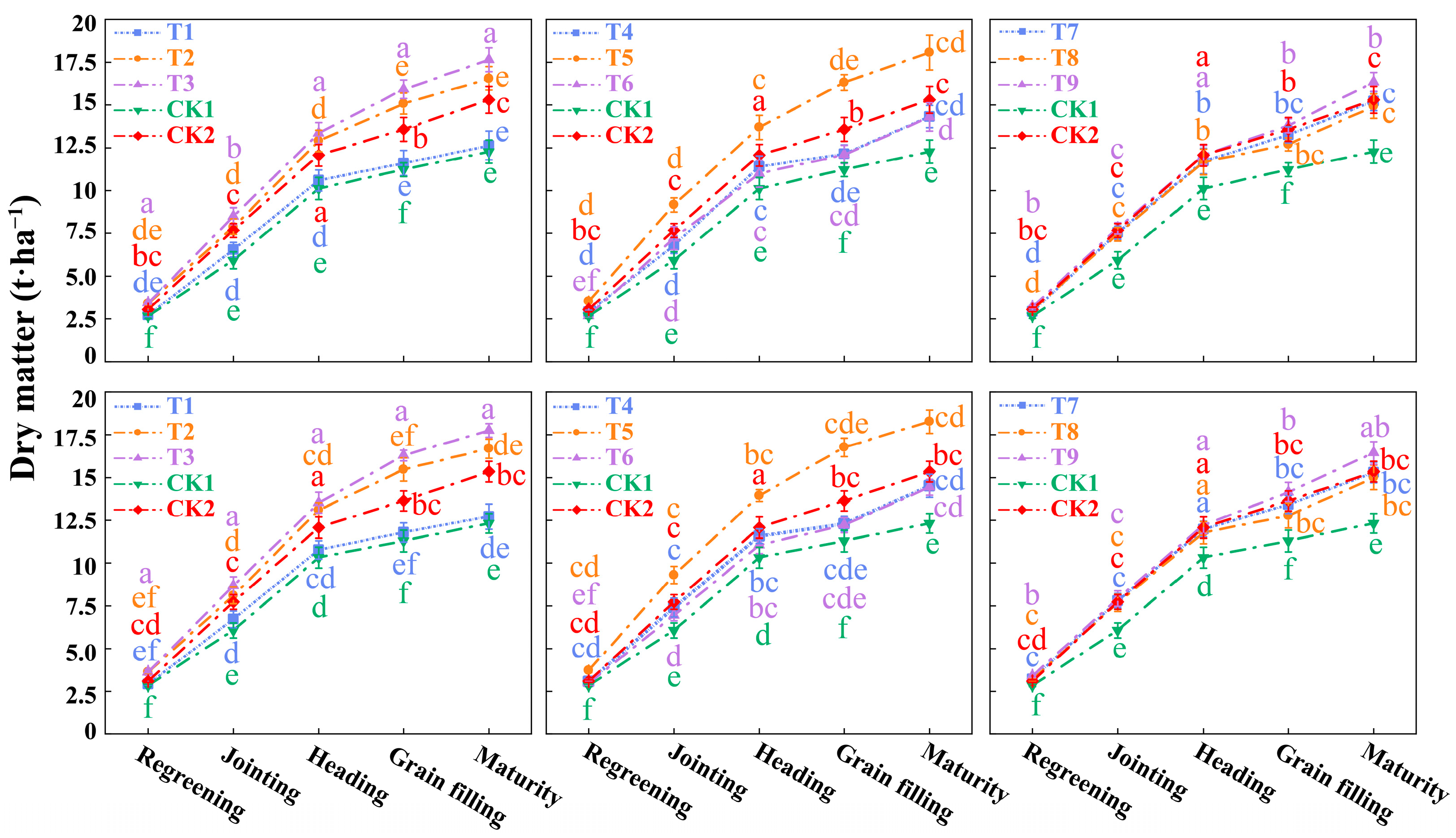

3.3. Plant Height and Dry Matter of Winter Wheat

3.4. Yield and Water and Nitrogen Utilization Efficiency of Winter Wheat

3.5. The Impact of Environmental Factors on Soil Quality and Yield of Winter Wheat

3.6. Multidimensional Path Analysis of Environmental Factors and Yield

3.7. Comprehensive Evaluation Based on Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS Method

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Water and Nitrogen Regulation on Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

4.2. Soil Microbial Communities’ Response to Water Nitrogen Regulation

4.3. The Effect of Water and Nitrogen Regulation on the Complexity of Microbial Co-Occurrence Net Works

4.4. Multidimensional Driving Mechanisms of Soil Quality and Microbial Communities on Wheat Yield

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Falkenmark, M. Growing Water Scarcity in Agriculture: Future Challenge to Global Water Security. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2013, 371, 20120410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global Food Demand and the Sustainable Intensification of Agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Song, S.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Meng, J.; Sweetman, A.J.; Wang, T. Impacts of Soil and Water Pollution on Food Safety and Health Risks in China. Environ. Int. 2015, 77, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Gao, Z.; Yang, Z. Rhizosphere Soil Properties, Microbial Community, and Enzyme Activities: Short-Term Responses to Partial Substitution of Chemical Fertilizer with Organic Manure. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Bom, F.; Nunes, I.; Raymond, N.S.; Hansen, V.; Bonnichsen, L.; Magid, J.; Jensen, L.S. Long-Term Fertilisation Form, Level and Duration Affect the Diversity, Structure and Functioning of Soil Microbial Communities in the Field. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 122, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Liu, Y.L.; Du, W.C.; Li, C.L.; Xu, M.L.; Xie, T.C.; Yin, Y.; Guo, H. Response of Soil Bacterial Communities, Antibiotic Residuals, and Crop Yields to Organic Fertilizer Substitution in North China Under Wheat–Maize Rotation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J. Soil Organic Matter Stratification Ratio as an Indicator of Soil Quality. Soil Tillage Res. 2002, 66, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Hazra, G.C.; Purakayastha, T.J.; Saha, N.; Mitran, T.; Roy, S.S.; Mandal, B. Establishment of Critical Limits of Indicators and Indices of Soil Quality in Rice–Rice Crop Systems Under Different Soil Orders. Geoderma 2017, 292, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooch, Y.; Ehsani, S.; Akbarinia, M. Stratification of Soil Organic Matter and Biota Dynamics in Natural and Anthropogenic Ecosystems. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 200, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xue, J.F.; Zhang, X.Q.; Kong, F.L.; Chen, F.; Lal, R.; Zhang, H.L. Stratification and Storage of Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen as Affected by Tillage Practices in the North China Plain. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünemann, E.K.; Bongiorno, G.; Bai, Z.; Creamer, R.E.; De Deyn, G.; De Goede, R.; Brussaard, L. Soil Quality—A Critical Review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 120, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Follstad Shah, J.J. Ecoenzymatic Stoichiometry and Ecological Theory. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2012, 43, 313–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Wood, S.A.; de Mesquita, C.P.B. How Microbes Can, and Cannot, Be Used to Assess Soil Health. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 153, 108111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, W.; Sun, T.; Ma, Y.; Chen, C.; Ma, Q.; Wu, L.; Xu, Q. Higher Yield Sustainability and Soil Quality by Manure Amendment than Straw Returning Under a Single-Rice Crop System. Field Crops Res. 2023, 292, 108805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemenschneider, C.; Al-Raggad, M.; Moeder, M.; Seiwert, B.; Salameh, E.; Reemtsma, T. Pharmaceuticals, Their Metabolites, and Other Polar Pollutants in Field-Grown Vegetables Irrigated with Treated Municipal Wastewater. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 5784–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Y. Long-Term Straw Mulching with Nitrogen Fertilization Increases Nutrient and Microbial Determinants of Soil Quality in a Maize–Wheat Rotation on China’s Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Du, X.; Li, Y.; Han, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Liang, W. Organic Substitutions Improve Soil Quality and Maize Yield Through Increasing Soil Microbial Diversity. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 347, 131323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ren, Y.; Jia, M.; Huang, S.; Guo, T.; Liu, B.; Jie, X. Improving Soil Quality and Crop Yield of Fluvo-Aquic Soils Through Long-Term Organic–Inorganic Fertilizer Combination: Promoting Microbial Community Optimization and Nutrient Utilization. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 104050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, K.K. Effects of Reduced Nitrogen and Suitable Soil Moisture on Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Rhizosphere Soil Microbiological, Biochemical Properties and Yield in the Huanghuai Plain, China. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Feng, H. Plastic Film Mulching Stimulates Brace Root Emergence and Soil Nutrient Absorption of Maize in an Arid Environment. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Feng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, A.; Zhang, Z. Spatial Distribution and Simulation of Soil Moisture and Salinity Under Mulched Drip Irrigation Combined with Tillage in an Arid Saline Irrigation District, Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 201, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Luo, X.; Wang, N.; Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Quan, H.; Feng, H. Transparent Plastic Film Combined with Deficit Irrigation Improves Hydrothermal Status of the Soil–Crop System and Spring Maize Growth in Arid Areas. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 265, 107536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Gao, F.; Wang, Y.; Lai, H.; Pan, X.; Li, X. A 2-Year Study on the Effects of Tillage and Straw Management on the Soil Quality and Peanut Yield in a Wheat–Peanut Rotation System. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 1698–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, S.; Liu, Z.; Zong, R.; Li, Q. Biodegradable Film Mulching Promotes Better Soil Quality and Increases Summer Maize Grain Yield in North China Plain. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69, 2493–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, F.L.; Fei, L.J.; Zhong, Y. Wetting Body Characteristics and Infiltration Model of Film Hole Irrigation. Water 2020, 12, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Mahmood, S. Application of Film Hole Irrigation on Borders for Water Saving and Sunflower Production. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2013, 38, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, K.; Ma, J.; He, H.; Liu, Y. Fish-Scale Pits with Diversion Holes Enhance Water Conservation in Semi-Arid Loess Soil: Experiments with Soil Columns, Mulching, and Simulated Rainfall. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2019, 19, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Fei, L.; Jie, F.; Hao, K.; Liu, L.; Shen, F.; Fan, Q. Effects of Bio-Organic Fertilizer on Soil Infiltration, Water Distribution, and Leaching Loss Under Muddy Water Irrigation Conditions. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duo, L.; Hu, Z. Soil Quality Change After Reclaiming Subsidence Land with Yellow River Sediments. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, D.L.; Page, A.L.; Helmke, P.A.; Loeppert, R.H. (Eds.) Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3: Chemical Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3: Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 961–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of Nitrogen in Soil by the Kjeldahl Method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahnke, W.C.; Johnson, G.V. Testing Soils for Available Nitrogen. In Soil Testing and Plant Analysis, 3rd ed.; Westerman, R.L., Ed.; SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1990; pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Liang, M.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Huang, E.; Yu, S. Abundance of Saprotrophic Fungi Determines Decomposition Rates of Leaf Litter from Arbuscular Mycorrhizal and Ectomycorrhizal Trees in a Subtropical Forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 107966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoc, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast Length Adjustment of Short Reads to Improve Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME Improves Sensitivity and Speed of Chimera Detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.Y.; Fei, L.J.; Peng, Y.L.; Zheng, R.Q.; Wang, Q.; Fan, Q.W.; Gao, Y.L. Optimized Water-Nitrogen Management Enhances Soil Nitrogen Cycling and Microbial Functions to Enhance Wheat Yield. In Plant Soil; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 10 July 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.E.; Alcon, F.; Diaz-Espejo, A.; Hernandez-Santana, V.; Cuevas, M.V. Water Use Indicators and Economic Analysis for On-Farm Irrigation Decision: A Case Study of a Super High Density Olive Tree Orchard. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 237, 106074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R. Editorial Note on Terms for Soil Analyses, Nutrient Content of Fertilizers and Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 289, 108547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.R. Historical Changes in Harvest Index and Crop Nitrogen Accumulation. Crop Sci. 1998, 38, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Lei, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Su, L.; Wang, Q.; Deng, M. Quantifying the Impact of Organic Fertilizers on Soil Quality Under Varied Irrigation Water Sources. Water 2023, 15, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzon, M.; Cavani, L.; Ciavatta, C.; Campanelli, G.; Burgio, G.; Marzadori, C. Conventional Versus Organic Management: Application of Simple and Complex Indexes to Assess Soil Quality. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 322, 107673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Qin, Y.; Tu, Q.; Yang, Y.; He, Z.; Zhou, J. Network Succession Reveals the Importance of Competition in Response to Emulsified Vegetable Oil Amendment for Uranium Bioremediation. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberán, A.; Bates, S.T.; Casamayor, E.O.; Fierer, N. Using Network Analysis to Explore Co-Occurrence Patterns in Soil Microbial Communities. ISME J. 2012, 6, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimerà, R.; Nunes Amaral, L.A. Functional Cartography of Complex Metabolic Networks. Nature 2005, 433, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, R.; Jumpponen, A.; Schlatter, D.C.; Paulitz, T.C.; Gardener, B.M.; Kinkel, L.L.; Garrett, K.A. Microbiome Networks: A Systems Framework for Identifying Candidate Microbial Assemblages for Disease Management. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Walder, F.; Büchi, L.; Meyer, M.; Held, A.Y.; Gattinger, A.; van der Heijden, M.G. Agricultural Intensification Reduces Microbial Network Complexity and the Abundance of Keystone Taxa in Roots. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1722–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F.; Fei, L.; Tuo, Y.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zheng, R.; Fan, Q. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Regulation on Soil Physicochemical Properties, Bacterial Diversity and Community Structure of Panax notoginseng. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 326, 112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhou, B.; Yang, X.; Salah, A.; Li, C.; Zhao, M. Effects of Straw-Return Method for the Maize–Rice Rotation System on Soil Properties and Crop Yields. Agronomy 2020, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, D.; Dang, P.; Wei, L.; Qin, X.; Siddique, K.H. Combined Ditch Buried Straw Return Technology in a Ridge–Furrow Plastic Film Mulch System: Implications for Crop Yield and Soil Organic Matter Dynamics. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 199, 104596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Lv, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, N. Optimization of Irrigation and N Fertilization Management Profoundly Increases Soil N Retention Potential in a Greenhouse Tomato Production Agroecosystem of Northeast China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 340, 108185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Gong, X.; Li, S.; Pang, J.; Chen, Z.; Sun, J. Optimizing Irrigation and Nitrogen Management Strategy to Trade Off Yield, Crop Water Productivity, Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Fruit Quality of Greenhouse-Grown Tomato. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 245, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Lu, X.; Zhou, K.; Chen, H.; Zhu, X.; Mori, T.; Mo, J. Effects of Long-Term Nitrogen and Phosphorus Additions on Soil Acidification in an N-Rich Tropical Forest. Geoderma 2017, 285, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, M.; Li, R.; Rasul, F.; Shahzad, S.; Wu, C.; Aamer, M. Soil Acidification and Salinity: The Importance of Biochar Application to Agricultural Soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1206820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, R.; Feng, G.; Yu, B. Evaluating the Effects of Agricultural Inputs on the Soil Quality of Smallholdings Using Improved Indices. Catena 2022, 209, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masto, R.E.; Chhonkar, P.K.; Singh, D.; Patra, A.K. Soil Quality Response to Long-Term Nutrient and Crop Management on a Semi-Arid Inceptisol. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 118, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.D.; Li, D.D.; Xu, J.H.; Zhou, Y.P.; Wang, Q.X. Effects of Application of Straw and Organic–Inorganic Fertilizers on Soil Quality and Wheat Yield in Different Texture Fluvo-Aquic Soils. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2024, 61, 1360–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, I.; Yang, L.; Ahmad, S.; Zeeshan, M.; Farooq, S.; Ali, I.; Zhou, X.B. Irrigation and Nitrogen Fertilization Alter Soil Bacterial Communities, Soil Enzyme Activities, and Nutrient Availability in Maize Crop. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 833758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Feng, K.; Yang, G.; Fu, W.; Chen, B. Nitrogen and Water Addition Regulate Soil Fungal Diversity and Co-Occurrence Networks. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 3192–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, X.; Zheng, C.; Suter, H.; Huang, Z. Different Responses of Soil Bacterial and Fungal Communities to Nitrogen Deposition in a Subtropical Forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Meng, F.; Ma, J. Impact of Drip Irrigation and Nitrogen Fertilization on Soil Microbial Diversity of Spring Maize. Plants 2022, 11, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y. Impacts of Fertilization Optimization on Soil Nitrogen Cycling and Wheat Nitrogen Utilization Under Water-Saving Irrigation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 878424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Y.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Liang, J.; Shi, R.; Wang, Z.; He, X. Effects of Water and Fertilizer Regulation on Soil Microbial Community, Fruit Nutrients, and Saponin Content of Panax notoginseng: A Three-Year Field Experiment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 220, 119166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.D.; Qin, X.R.; Li, T.L.; Cao, H.B. Effects of Planting Patterns Plastic Film Mulching on Soil Temperature, Moisture, Functional Bacteria and Yield of Winter Wheat in the Loess Plateau of China. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 1560–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisermann, A.; Maron, P.A.; Beaumelle, L.; Lata, J.C. Fungal Communities Are More Sensitive Indicators to Non-Extreme Soil Moisture Variations than Bacterial Communities. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015, 86, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, A. What Is Microbial Community Ecology? ISME J. 2009, 3, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Reich, P.B.; Trivedi, C.; Eldridge, D.J.; Abades, S.; Alfaro, F.D.; Singh, B.K. Multiple Elements of Soil Biodiversity Drive Ecosystem Functions Across Biomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, S.; Avera, B.N.; Strahm, B.D.; Badgley, B.D. Soil Bacterial and Fungal Communities Show Distinct Recovery Patterns During Forest Ecosystem Restoration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00966-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Yan, Q.; Deng, Y.; Michaletz, S.T.; Buzzard, V.; Weiser, M.D.; Zhou, J. Biogeographic Patterns of Microbial Co-Occurrence Ecological Networks in Six American Forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 107897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z.; Lu, D.; Zhu, D.; Deng, P. Effect of Nitrogen Root Zone Fertilization on Rice Yield, Uptake and Utilization of Macronutrient in Lower Reaches of Yangtze River, China. Paddy Water Environ. 2017, 15, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhao, Z.; Gong, Q.; Zhai, B.; Li, Z. Responses of Fungal–Bacterial Community and Network to Organic Inputs Vary Among Different Spatial Habitats in Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 125, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shi, F.; Yi, S.; Feng, T.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Zhai, B. Soil Multifunctionality Predicted by Bacterial Network Complexity Explains Differences in Wheat Productivity Induced by Fertilization Management. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 153, 127058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Yue, S.; Tian, J.; Chen, H.; Jiang, H.; Yu, Q. Soil Microbial Community and Network Changes After Long-Term Use of Plastic Mulch and Nitrogen Fertilization on Semiarid Farmland. Geoderma 2021, 396, 115086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Shang, Y.; Yang, X.; Yu, A. Drive Soil Nitrogen Transformation and Improve Crop Nitrogen Absorption and Utilization—A Review of Green Manure Applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1305600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liao, D.; Rengel, Z.; Shen, J. Soil–Plant–Microbe Interactions in the Rhizosphere: Incremental Amplification Induced by Localized Fertilization. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, X.; Cao, W.; Li, Q. Negative Interactions Between Bacteria and Fungi Modulate Life History Strategies of Soil Bacterial Communities in Temperate Shrublands Under Precipitation Gradients. Funct. Ecol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Furtak, K. Soil–Plant–Microbe Interactions Determine Soil Biological Fertility by Altering Rhizospheric Nutrient Cycling and Biocrust Formation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Fan, X.; Chen, H.; Ye, M.; Yin, C.; Wu, C.; Liang, Y. The Response Patterns of r-and K-Strategist Bacteria to Long-Term Organic and Inorganic Fertilization Regimes Within the Microbial Food Web Are Closely Linked to Rice Production. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 942, 173681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Kang, P.; Tan, M.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Root Exudates and Rhizosphere Soil Bacterial Relationships of Nitraria tangutorum Are Linked to k-Strategists Bacterial Community Under Salt Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 997292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mo, C.; Pan, Y.; Yang, P.; Ding, X.; Lei, Q.; Kang, P. Responses of Soil Microbial Survival Strategies and Functional Changes to Wet–Dry Cycle Events. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.T.; Supronienė, S.; Žvirdauskienė, R.; Aleinikovienė, J. Climate, Soil, and Microbes: Interactions Shaping Organic Matter Decomposition in Croplands. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Yin, B.; Ye, Z.; Kang, J.; Sun, R.; Wu, Z. Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms Drive K Strategists Through Deterministic Processes to Alleviate Biological Stress Caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 289, 127911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunlid, A.; Floudas, D.; Op De Beeck, M.; Wang, T.; Persson, P. Decomposition of Soil Organic Matter by Ectomycorrhizal Fungi: Mechanisms and Consequences for Organic Nitrogen Uptake and Soil Carbon Stabilization. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 934409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Trigueros, C.A.; Frew, A. Connecting the Dots: Network Structure as a Functional Trait in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Plants People Planet 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, H.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Xie, X.N.; Wang, E.; Martin, F.; Yuan, Z. Phosphorus/Nitrogen Sensing and Signaling in Diverse Root–Fungus Symbioses. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, M.M.; Siddiqui, S. New Insights in Enhancing the Phosphorus Use Efficiency Using Phosphate-Solubilizing Microorganisms and Their Role in Crop System. Geomicrobiol. J. 2024, 41, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Song, X.; Zheng, W.; Wu, L.; Chen, Q.; Yu, X.; Zhang, M. The Controlled-Release Nitrogen Fertilizer Driving the Symbiosis of Microbial Communities to Improve Wheat Productivity and Soil Fertility. Field Crops Res. 2022, 289, 108712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeaka, H.N.; Akinsemolu, A.A.; Siyanbola, K.F.; Adetunji, V.A. Green Microbe Profile: Rhizophagus intraradices—A Review of Benevolent Fungi Promoting Plant Health and Sustainability. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 15, 1028–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Sediment Concentration (kg·m−3) | Irrigation Levels (FC) | Nitrogen Application (kg·ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 3 | 0.50–0.65 | 100 |

| T2 | 0.65–0.80 | 220 | |

| T3 | 0.80–0.95 | 160 | |

| T4 | 6 | 0.50–0.65 | 220 |

| T5 | 0.65–0.80 | 160 | |

| T6 | 0.80–0.95 | 100 | |

| T7 | 9 | 0.50–0.65 | 160 |

| T8 | 0.65–0.80 | 100 | |

| T9 | 0.80–0.95 | 220 | |

| CK1 | 0 | 0.80–0.95 | 0 |

| CK2 | 0.80–0.95 | 220 |

| Treatments | Bacterial | Fungal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chao1 | Shannon | Simpson | ACE | Richness | Chao1 | Shannon | Simpson | ACE | Richness | |

| T1 | 1758.5 i | 9.45 f | 0.9953 c | 1964.29 e | 1821.85 f | 135.71 h | 2.89 g | 0.75 g | 184.15 f | 160.14 d |

| T2 | 2301.3 b | 9.79 a | 0.9965 a | 2314.65 b | 2397.85 ab | 221.37 a | 4.16 b | 0.89 b | 225.6 a | 391.27 b |

| T3 | 2082.99 d | 9.61 c | 0.9959 b | 2078.45 d | 2124.43 c | 169.86 f | 3.58 d | 0.82 d | 179.23 h | 191.68 cd |

| T4 | 1822.03 h | 9.55 d | 0.9963 a | 1813.51 g | 1866.13 f | 175.11 e | 3.33 e | 0.77 f | 188.61 e | 176.65 d |

| T5 | 2419.02 a | 9.65 b | 0.9965 a | 2436.97 a | 2473.96 a | 203.72 b | 5.26 a | 0.93 a | 191.58 c | 528.46 a |

| T6 | 2191.86 c | 9.51 e | 0.9951 c | 2202.92 c | 2295.5 b | 155.15 g | 3.13 f | 0.79 e | 134.18 i | 181.61 d |

| T7 | 1965.97 f | 9.31 i | 0.9956 b | 1973.95 e | 2037.18 cd | 178.22 d | 3.12 f | 0.86 c | 180.54 g | 184.54 d |

| T8 | 1967.65 e | 9.35 h | 0.995 c | 1755.75 h | 1914.66 ef | 177.29 d | 3.74 c | 0.78 ef | 190.57 d | 170.59 d |

| T9 | 1882.82 g | 9.41 g | 0.9963 a | 1882.38 f | 1995.8 de | 188.03 c | 4.15 b | 0.86 c | 195.99 b | 227.37 c |

| CK1 | 1577.05 k | 9.08 k | 0.9942 e | 1558 j | 1597.48 g | 84 j | 2.29 h | 0.56 i | 96.45 k | 69.91 f |

| CK2 | 1632.09 j | 9.17 j | 0.9946 d | 1626.03 i | 1670.77 g | 111.23 i | 2.92 g | 0.72 h | 122.95 j | 115.87 e |

| Treatment | D+ | D− | C | Sort Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 60.50 | 24.760 | 0.290 | 10 |

| T2 | 22.531 | 56.132 | 0.714 | 3 |

| T3 | 17.361 | 66.041 | 0.792 | 2 |

| T4 | 44.709 | 40.465 | 0.475 | 6 |

| T5 | 0.730 | 78.266 | 0.991 | 1 |

| T6 | 54.375 | 27.763 | 0.338 | 9 |

| T7 | 38.753 | 52.980 | 0.578 | 5 |

| T8 | 46.087 | 33.072 | 0.418 | 7 |

| T9 | 27.601 | 51.765 | 0.652 | 4 |

| CK1 | 78.134 | 2.005 | 0.025 | 11 |

| CK2 | 54.869 | 35.102 | 0.390 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, F.; Fei, L.; Peng, Y.; Gao, Y. Water–Nitrogen Coupling Under Film Mulching Synergistically Enhances Soil Quality and Winter Wheat Yield by Restructuring Soil Microbial Co-Occurrence Networks. Plants 2025, 14, 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223461

Shen F, Fei L, Peng Y, Gao Y. Water–Nitrogen Coupling Under Film Mulching Synergistically Enhances Soil Quality and Winter Wheat Yield by Restructuring Soil Microbial Co-Occurrence Networks. Plants. 2025; 14(22):3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223461

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Fangyuan, Liangjun Fei, Youliang Peng, and Yalin Gao. 2025. "Water–Nitrogen Coupling Under Film Mulching Synergistically Enhances Soil Quality and Winter Wheat Yield by Restructuring Soil Microbial Co-Occurrence Networks" Plants 14, no. 22: 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223461

APA StyleShen, F., Fei, L., Peng, Y., & Gao, Y. (2025). Water–Nitrogen Coupling Under Film Mulching Synergistically Enhances Soil Quality and Winter Wheat Yield by Restructuring Soil Microbial Co-Occurrence Networks. Plants, 14(22), 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223461