Characterization of Endoglucanase (GH9) Gene Family in Tomato and Its Expression in Response to Rhizophagus irregularis and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Characterization of the Endoglucanase (GH9) Gene Family in Solanum lycopersicum L.

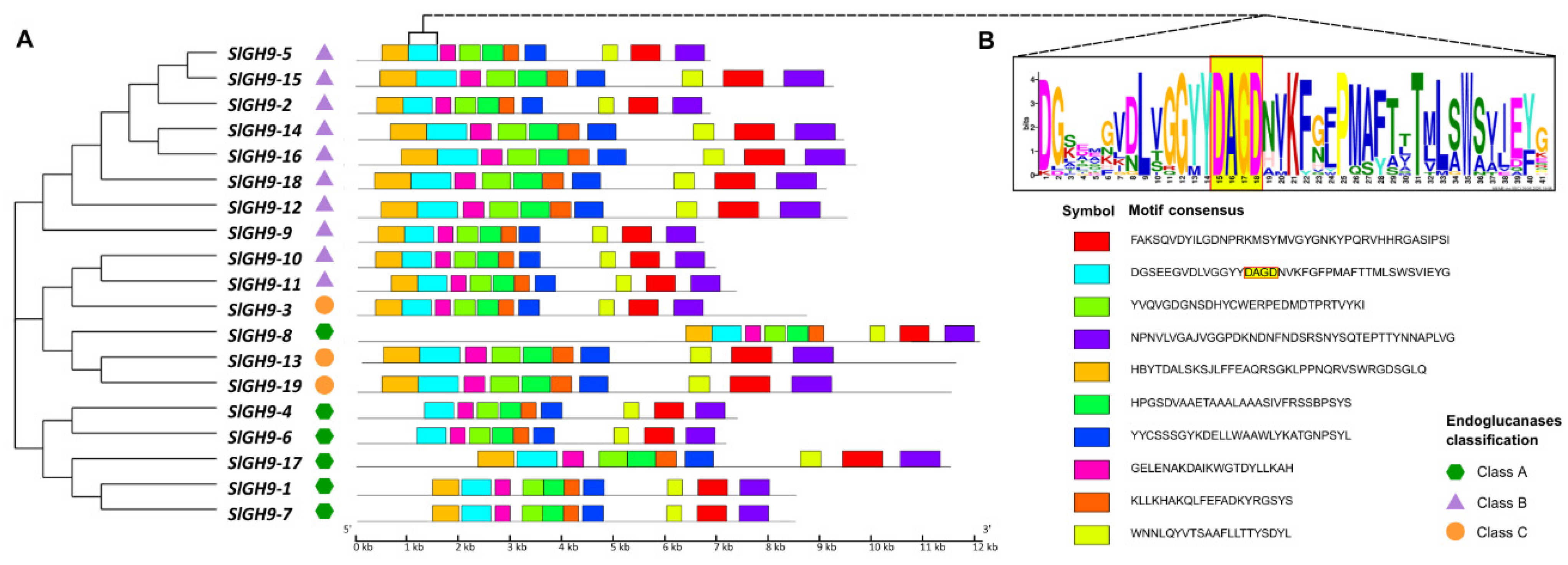

2.2. Analysis of Gene Structures, Protein Domains, Conserved Motifs, and Predicted Protein Structures of the SlGH9 Family

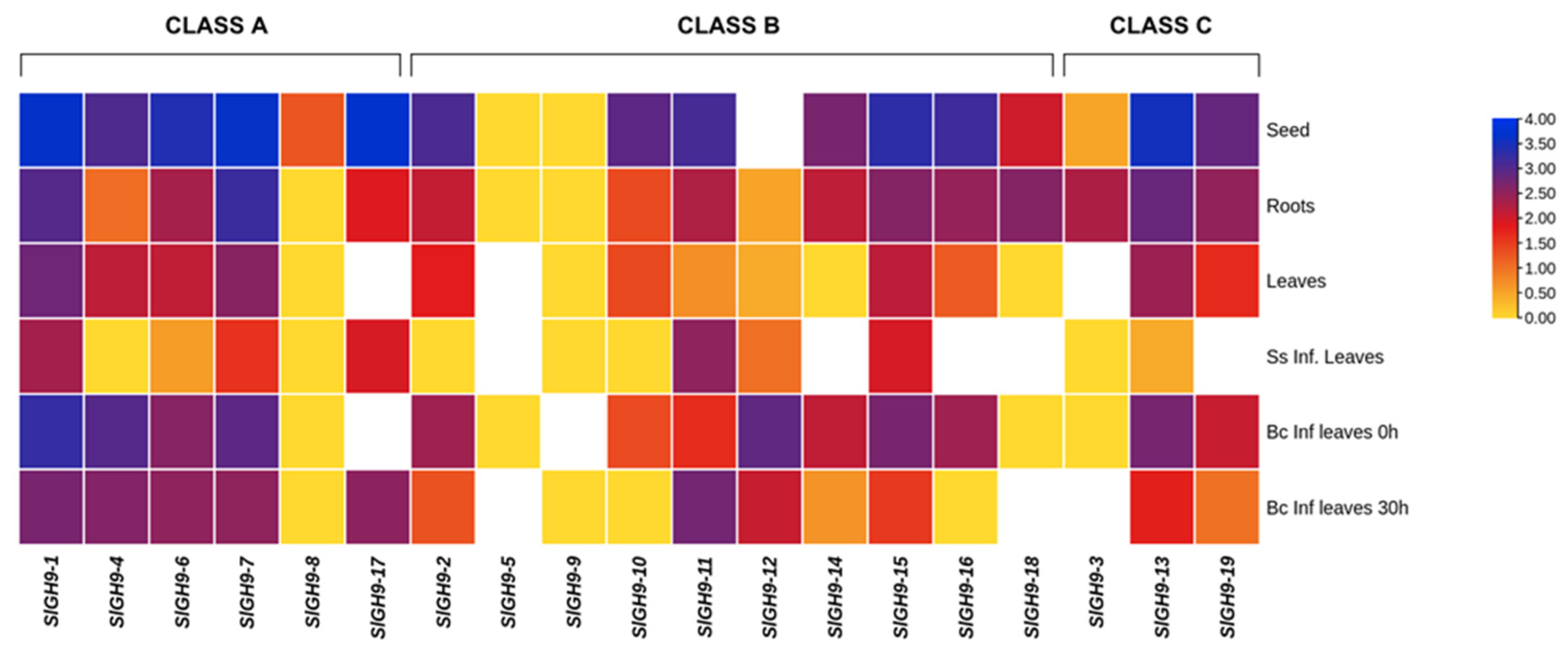

2.3. Expression Patterns of SlGH9 Genes in Different Tissues

2.4. Chromosome Mapping and SlGH9 Gene Duplication Analysis

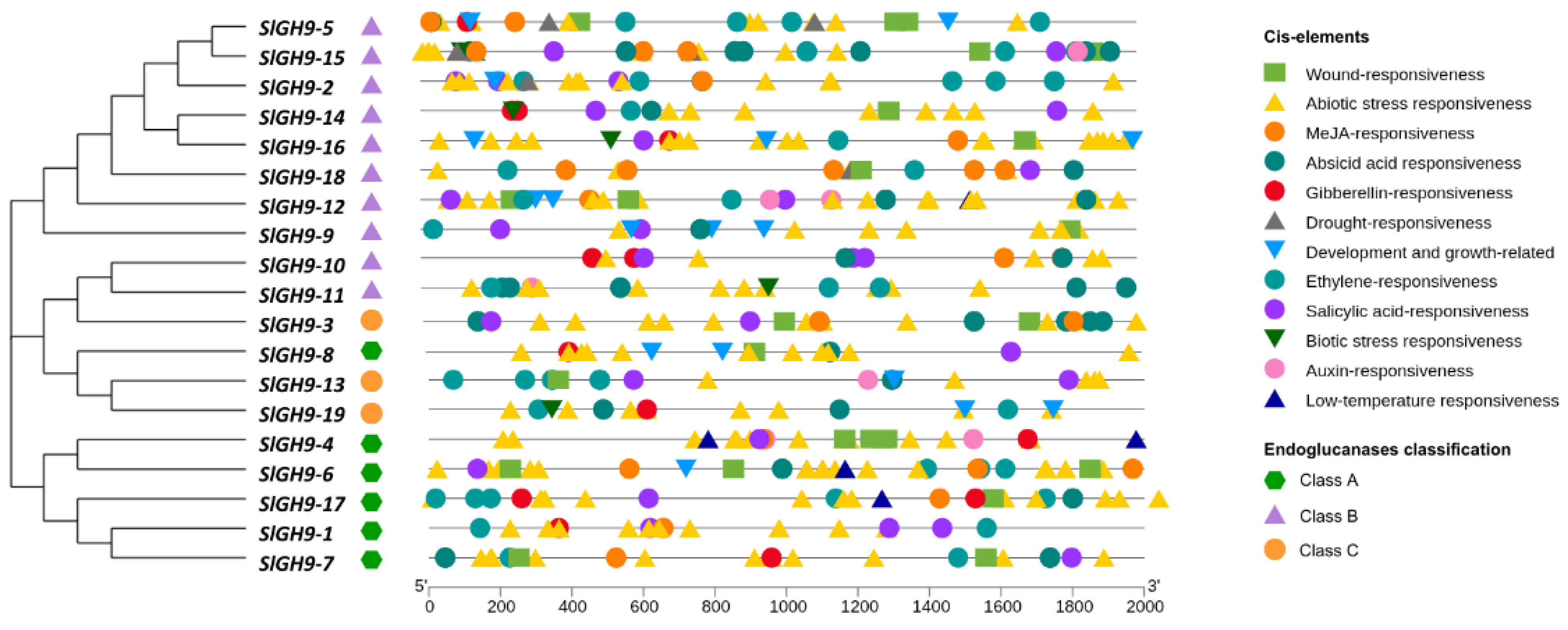

2.5. Promoter Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements of the S. lycopersicum GH9 Gene Family

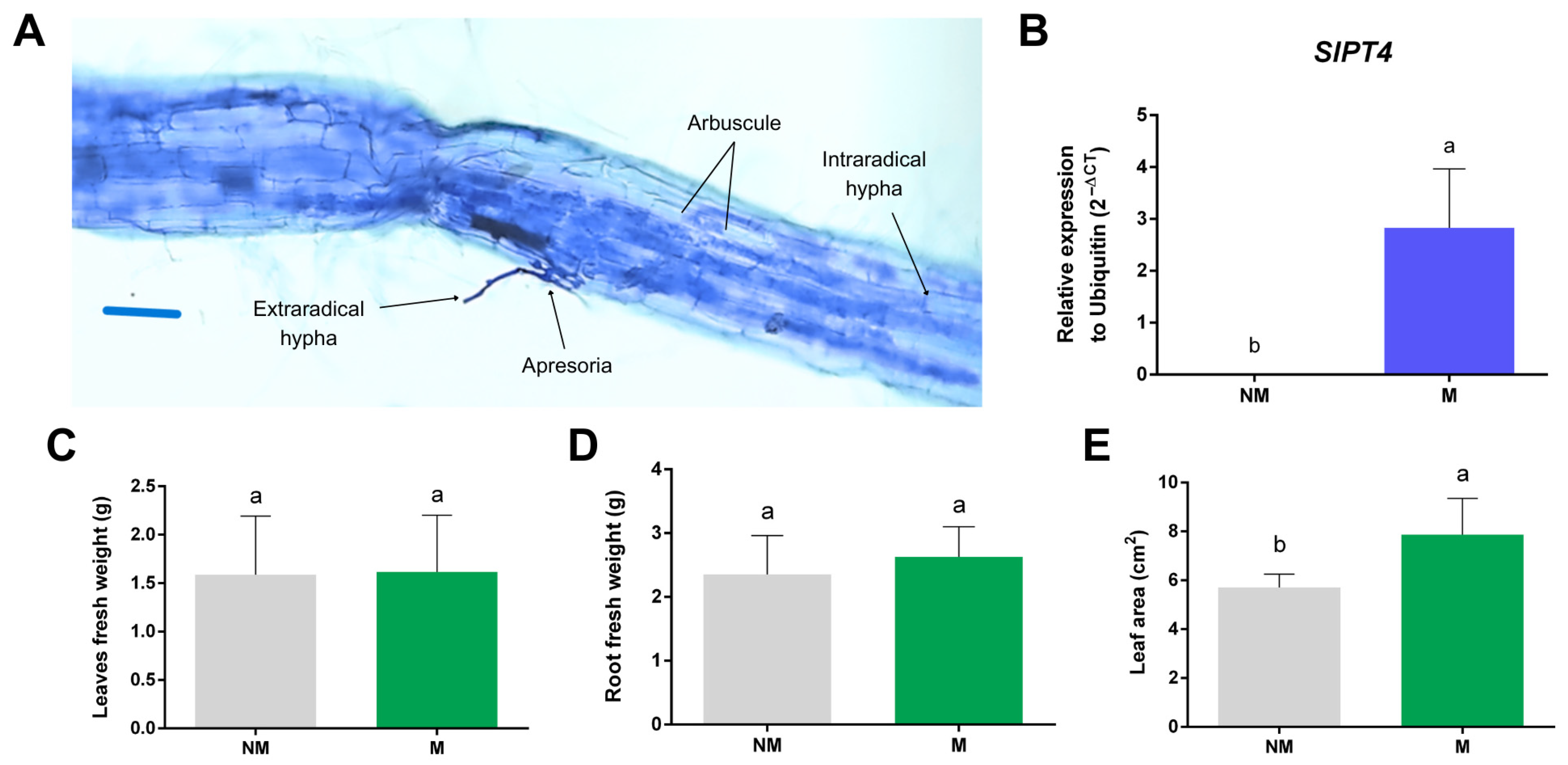

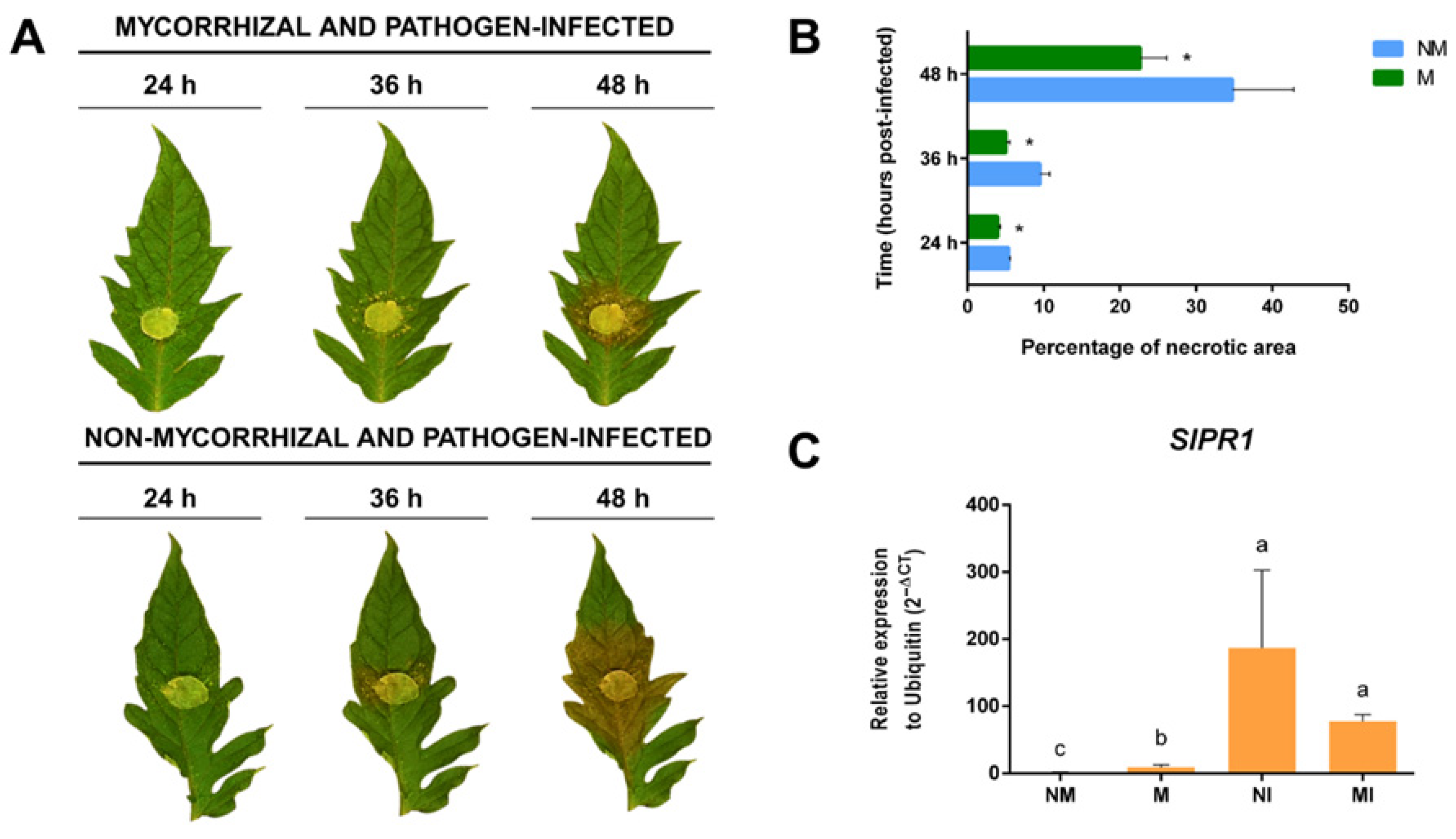

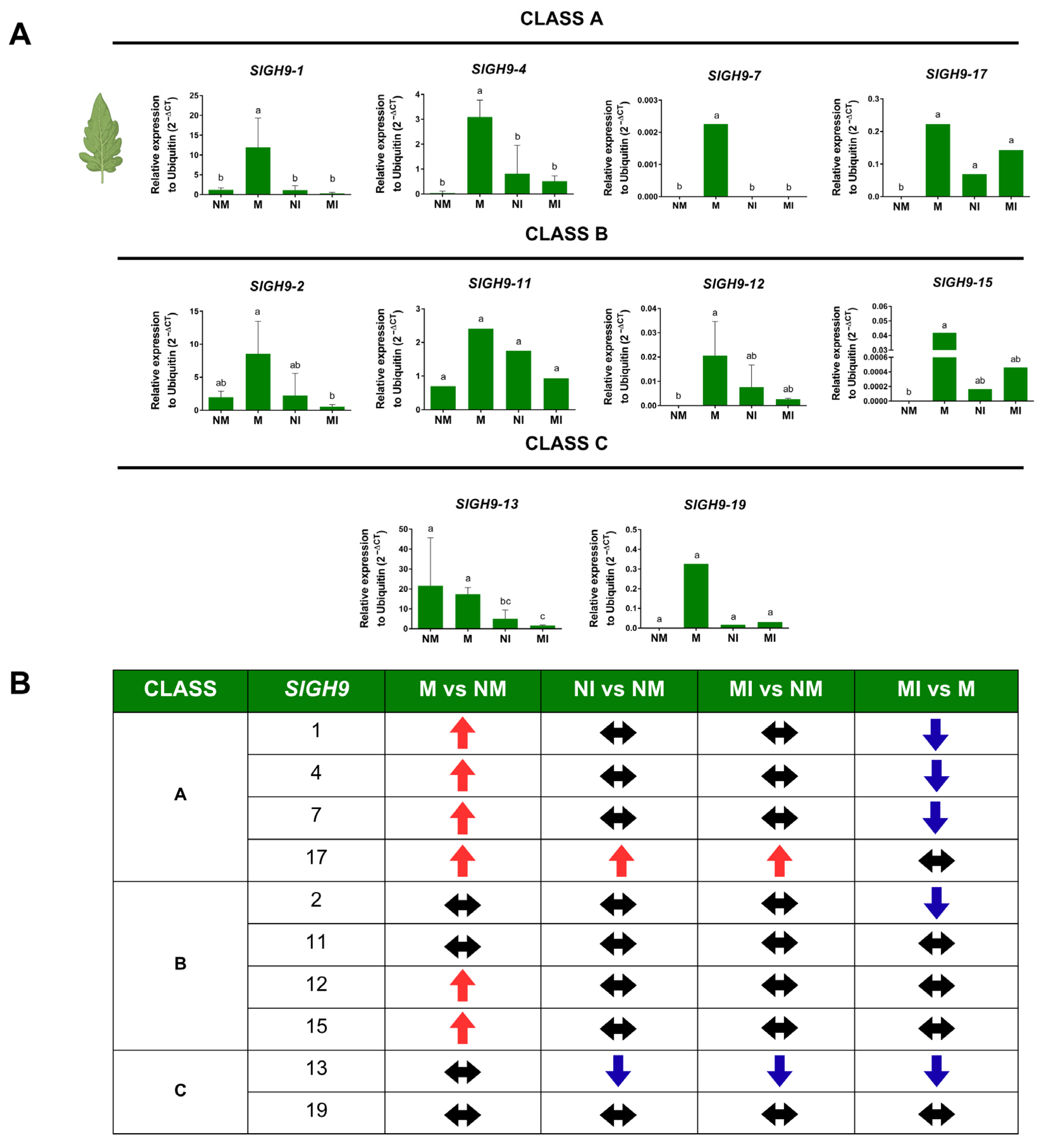

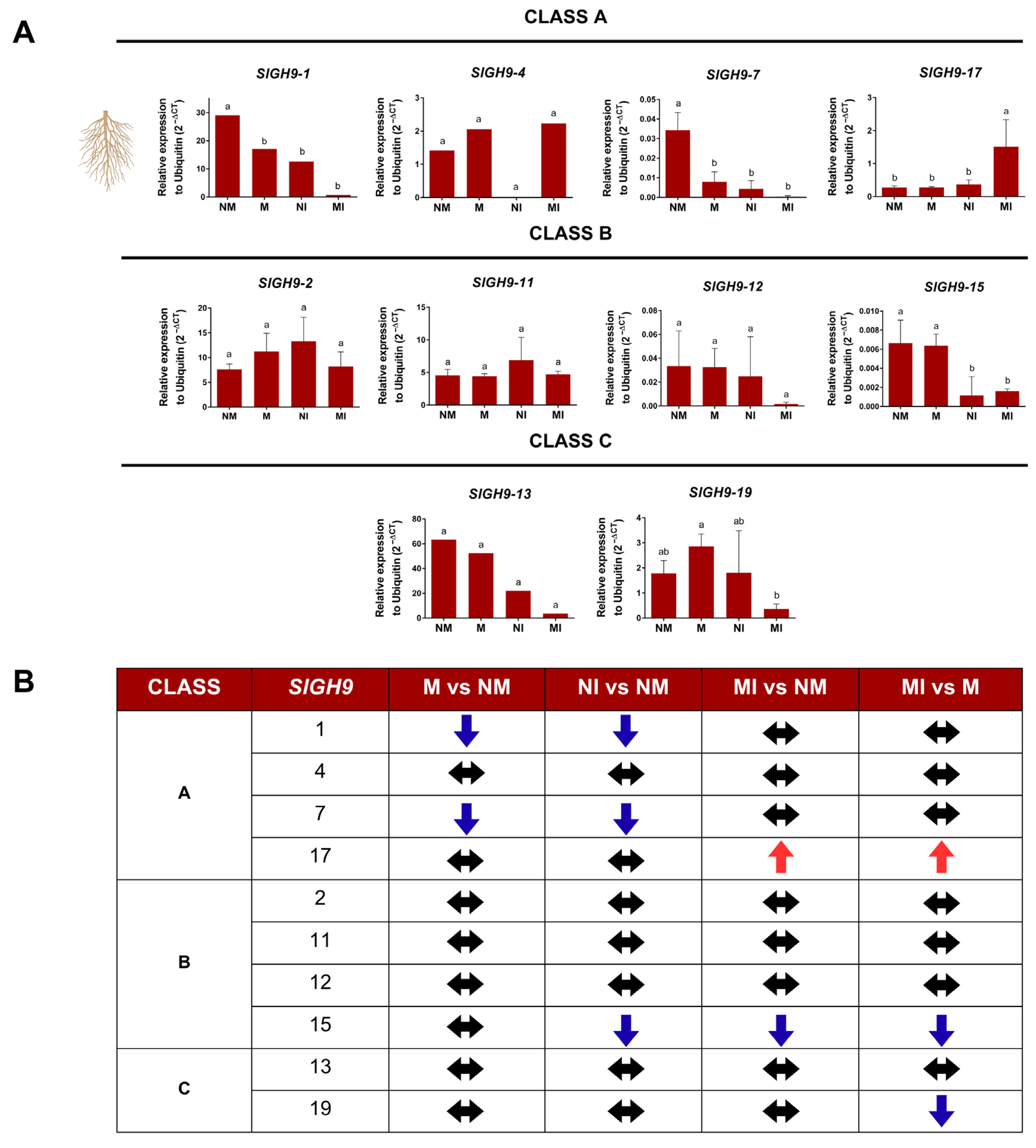

2.6. SlGH9 Gene Expression Profile in Response to Interactions with Beneficial and Pathogenic Fungi

2.7. Association Network Analysis of SlGH9 Protein

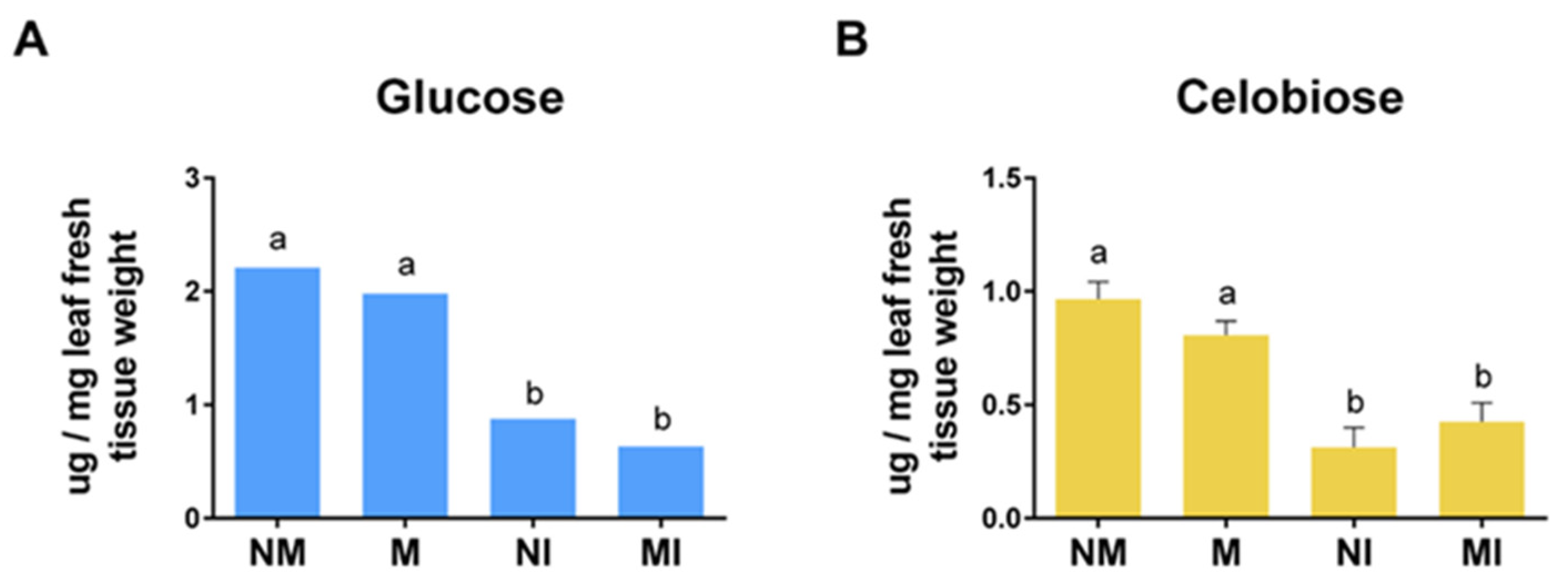

2.8. Cellobiose and Glucose Content in Tomato Leaves

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of Endoglucanase Gene Family Members (SlGH9) in Solanum lycopersicum L.

4.2. Gene Structure Analysis, Multiple Sequence Alignment, and Conserved Motif Identification

4.3. Sequence Alignment and 3D Structure Prediction of SlGH9 Proteins

4.4. Chromosome Distribution, Gene Duplication Events, and Analysis of Ka/Ks Ratios of SlGH9 Genes

4.5. Analysis of Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements of Tomato GH9 Genes

4.6. In Silico Gene Expression Analysis

4.7. Protein–Protein Interaction Network

4.8. Plant and Fungal Materials and Bioassays

4.9. cDNA Synthesis, Primer Design, and Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

4.10. Extraction and Quantification of Sugars in the Leaf Tissue of Tomato Plants

4.11. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keegstra, K. Plant cell walls. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y. The plant cell wall: Biosynthesis, construction, and functions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Jordá, L.; Torres, M.Á.; Martín-Dacal, M.; Berlanga, D.J.; Fernández-Calvo, P.; Gómez-Rubio, E.; Martín-Santamaría, S. Plant cell wall-mediated disease resistance: Current understanding and future perspectives. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 699–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzert, K.S.; Esngelsdorf, T. Plant cell wall structure and dynamics in plant–pathogen interactions and pathogen defence. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpita, N.C.; McCann, M.C. Redesigning plant cell walls for the biomass-based bioeconomy. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15144–15157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delmer, D.; Dixon, R.A.; Keegstra, K.; Mohnen, D. The plant cell wall-dynamic, strong, and adaptable-is a natural shapeshifter. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 1257–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.G. Regulation of cellulose synthesis—aNOther player in the game? New Phytol. 2008, 179, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Kwak, J.H.; Conrad Zhang, Z.; Brown, H.M.; Arey, B.W.; Holladay, J.E. Studying cellulose fiber structure by SEM, XRD, NMR and acid hydrolysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 68, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, H.E.; Döring, A.; Persson, S. The cell biology of cellulose synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Qin, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, M.; Hao, D.C.; Yin, H. An endoglucanase from Erwinia amylovora induces broad-spectrum immune response in plants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanowicz, B.R.; Catalá, C.; Irwin, D.; Wilson, D.B.; Ripoll, D.R.; Rose, J.K. A tomato endo-beta-1,4-glucanase, SlCel9C1, represents a distinct subclass with a new family of carbohydrate binding modules (CBM49). J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 12066–12074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.J.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, I.G.; Kim, K.H. Synergistic proteins for the enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose by cellulase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 8469–8480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, K.D.; Zhang, P.Y.; Zhou, X.; Ma, X.Q.; Li, F.L. Synergistic Cellulose Hydrolysis Dominated by a Multi-Modular Processive Endoglucanase from Clostridium cellulosi. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagl, M.; Haske-Cornelius, O.; Skopek, L. Biorefining: The role of endoglucanases in refining of cellulose fibers. Cellulose 2021, 28, 7633–7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynd, L.R.; van Zyl, W.H.; McBride, J.E.; Laser, M. Consolidated bioprocessing of cellulosic biomass: An update. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005, 16, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libertini, E.; Li, Y.; McQueen-Mason, S.J. Phylogenetic Analysis of the Plant Endo-β-1,4-Glucanase Gene Family. J. Mol. Evol. 2004, 58, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, M.; Barkwill, S.; Unda, F.; Mansfield, S.D. Endo-β-1,4-glucanases impact plant cell wall development by influencing cellulose crystallization. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2015, 57, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, F.; His, I.; Jauneau, A.; Vernhettes, S.; Canut, H.; Höfte, H. A plasma membrane-bound putative endo-1,4-beta-D-glucanase is required for normal wall assembly and cell elongation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 5563–5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Campillo, E.; Bennett, A.B. Pedicel Breakstrength and Cellulase Gene Expression during Tomato Flower Abscission. Plant Physiol. 1996, 111, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalá, C.; Rose, J.K.; Bennett, A.B. Auxin regulation and spatial localization of an endo-1,4-beta-D-glucanase and a xyloglucan endotransglycosylase in expanding tomato hypocotyls. Plant J. 1997, 12, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummell, D.A.; Bird, C.R.; Schuch, W.; Bennett, A.B. An endo-1,4-beta-glucanase expressed at high levels in rapidly expanding tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997, 33, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaitzis, P.; Hong, S.B.; Solomos, T.; Tucker, M.L. Molecular characterization of a tomato endo-beta-1,4-glucanase gene expressed in mature pistils, abscission zones and fruit. Plant Cell Physiol. 1999, 40, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Real, M.D.; Company, P.; García-Agustín, P.; Bennett, A.B.; González-Bosch, C. Characterization of tomato endo-beta-1,4-glucanase Cel1 protein in fruit during ripening and after fungal infection. Planta 2004, 220, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flors, V.; Leyva, M.d.l.O.; Vicedo, B.; Finiti, I.; Real, M.D.; García-Agustín, P.; Bennett, A.B.; González-Bosch, C. Absence of the endo-beta-1,4-glucanases Cel1 and Cel2 reduces susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea in tomato. Plant J. 2007, 52, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorilli, V.; Martínez-Medina, A.; Pozo, M.J.; Lanfranco, L. Plant Immunity Modulation in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis and Its Impact on Pathogens and Pests. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2024, 62, 127–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, V.; Genre, A.; Balestrini, R.; Cappellazzo, G.; Dewit, P.J.; Bonfante, P. Transcriptome analysis of arbuscular mycorrhizal roots during development of the prepenetration apparatus. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioli, A.; Zouari, I.; Chalot, M.; Bonfante, P. The arbuscular mycorrhizal status has an impact on the transcriptome profile and amino acid composition of tomato fruit. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Gámez, R.G.; Bueno-Ibarra, M.A.; Cruz-Mendívil, A.; Calderón-Vázquez, C.L.; Ramírez-Douriet, C.M.; Maldonado-Mendoza, I.E.; Villalobos-López, M.Á.; Valdez-Ortíz, Á.; López-Meyer, M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis-induced expression changes in Solanum lycopersicum leaves revealed by RNA-seq analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2016, 34, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentpéteri, V.; Virág, E.; Mayer, Z.; Duc, N.H.; Hegedűs, G.; Posta, K. First Peek into the Transcriptomic Response in Heat-Stressed Tomato Inoculated with Septoglomus constrictum. Plants 2024, 13, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Garrido, J.M.; Cabello, M.N.; García-Romera, I.; Ocampo, J.A. Endoglucanase activity in lettuce plants colonized with the vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus fasciculatum. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1992, 24, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Blaylock, L.A.; Endre, G.; Cho, J.; Town, C.D.; VandenBosch, K.A.; Harrison, M.J. Transcript profiling coupled with spatial expression analyses reveals genes involved in distinct developmental stages of an arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 2106–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guether, M.; Balestrini, R.; Hannah, M.; He, J.; Udvardi, M.K.; Bonfante, P. Genome-wide reprogramming of regulatory networks, transport, cell wall and membrane biogenesis during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in Lotus japonicus. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Gong, C.; Zhang, D. Populus endo-β-1,4-glucanases gene family: Genomic organization, phylogenetic analysis, expression profiles and association mapping. Planta 2015, 241, 1417–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomer, X.; Llop-tous, I.; Vendrell, M.; Krens, A.F.; Schaart, G.J.; Boone, J.M.; Valk, H.; Salentijin, E.M.J. Antisense down-regulation of strawberry endo-β-(1,4)-glucanase genes does not prevent fruit softening during ripening. Plant Sci. 2006, 171, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainotti, L.; Pavanello, A.; Zanin, D. PpEG4 is a peach endo-beta-1,4-glucanase gene whose expression in climacteric peaches does not follow a climacteric pattern. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xiong, M.; Lu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ouyang, B. Systematic Analysis of the Grafting-Related Glucanase-Encoding GH9 Family Genes in Pepper, Tomato and Tobacco. Plants 2022, 11, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, R.; Chen, B.; Zhong, Z.; Jiang, F. SlGH9-15 regulates tomato fruit cracking with hormonal and abiotic stress responsiveness cis-elements. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, G.; Sergeant, K.; Legay, S.; Hausman, J.F.; Cauchie, H.M.; Ahmad, I.; Siddiqui, K.S. Novel Insights from Comparative In Silico Analysis of Green Microalgal Cellulases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Bertoni, D.; Magana, P.; Paramval, U.; Pidruchna, I.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Tsenkov, M.; Nair, S.; Mirdita, M.; Yeo, J.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: Providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.T.; Chao, Y.T.; Chen, W.C.; Shih, M.C.; Chang, S.B. Segmental and tandem chromosome duplications led to divergent evolution of the chalcone synthase gene family in Phalaenopsis orchids. Ann. Bot. 2019, 123, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.W.; Tominaga, R.; Sugiyama, J.; Furuta, Y.; Tanimoto, E.; Samejima, M.; Sakai, F.; Hayashi, T. Enhancement of growth by expression of poplar cellulase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2003, 33, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somerville, C. Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006, 22, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, S.; Paredez, A.; Carroll, A.; Palsdottir, H.; Doblin, M.; Poindexter, P.; Khitrov, N.; Auer, M.; Somerville, C.R. Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15566–15571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeron-Santiago, I.A.; Martínez-Trujillo, M.; Valdez-Alarcón, J.J.; Pedraza-Santos, M.E.; Santoyo, G.; López, P.A.; Pozo, M.J.; Chávez-Barcenas, A.T. Carbohydrate and lipid balances in the positive plant phenotypic response to arbuscular mycorrhiza: Increase in sink strength. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e13857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventis, G.; Tsiknia, M.; Feka, M.; Ladikou, E.V.; Papadakis, I.E.; Chatzipavlidis, I.; Papadopoulou, K.; Ehaliotis, C. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance growth of tomato under normal and drought conditions, via different water regulation mechanisms. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R.; Setiawati, T.; Sukiman, D.; Nurzaman, M. The arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation affects plant growth and flavonoid content in tomato plant (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.). J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2024, 10, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Webster, S.; He, S.Y. Growth-defense trade-offs in plants. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Sharma, R. Origin, evolution, and divergence of plant class C GH9 endoglucanases. BMC Evol. Biol. 2018, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Maldonado-Mendoza, I.; Lopez-Meyer, M.; Cheung, F.; Town, C.D.; Harrison, M.J. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis is accompanied by local and systemic alterations in gene expression and an increase in disease resistance in the shoots. Plant J. 2007, 50, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAZypedia. GH1 Family. The CAZypedia Consortium. 2024. Available online: https://www.cazypedia.org/index.php/Glycoside_Hydrolase_Family_1 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Dulermo, T.; Rascle, C.; Chinnici, G.; Gout, E.; Bligny, R.; Cotton, P. Dynamic carbon transfer during pathogenesis of sunflower by the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea: From plant hexoses to mannitol. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amselem, J.; Cuomo, C.A.; van Kan, J.A.; Viaud, M.; Benito, E.P.; Couloux, A.; Coutinho, P.M.; de Vries, R.P.; Dyer, P.S.; Fillinger, S.; et al. Genomic analysis of the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Xia, R. A painless way to customize Circos plot: From data preparation to visualization using TBtools. iMeta 2022, 1, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira, F.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Lee, J.; Eusebi, A.; Niewielska, A.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Lopez, R.; Butcher, S. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, M.A.; Haubold, B.; Mitchell-Olds, T. Comparative evolutionary analysis of chalcone synthase and alcohol dehydrogenase loci n Arabidopsis, Arabis, and related genera (Brassicaceae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Tomato Genome Consortium. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 2012, 485, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnon, D.I. The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. Soil Sci. 1950, 48, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J.M.; Hayman, D.S. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1970, 55, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, M.; Mosse, B. An evaluation of techniques for measuring vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal infection in roots. New Phytol. 1980, 84, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeyner, A.; Gefrom, A.; Hillegeist, D.; Sommer, M.C.; Greef, J.M. Contribution to the Method of Sugar Analysis in Legume Grains for Ensiling—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2015, 1, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

| Name | Gene ID | Location | Size | Class | Subcellular Localization | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL5.0 | SL4.0 | Chr | Start/End | Genomic | Transcript | 5′ UTR | 3′ UTR | Protein | PI | MW (KDa) | |||

| SlGH9-1 | Solyc01G003470 | Solyc01g102580 | 1 | 86,055,748/86,059,426 | 3678 | 2242 | 107 | 281 | 618 | 8.9 | 68.5 | A | Cell membrane |

| SlGH9-2 | Solyc01G004213 | Solyc01g110340 | 1 | 91,850,248/91,856,033 | 5785 | 1491 | 0 | 0 | 497 * | 4.9 * | 55.2 * | B | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-3 | Solyc02G000158 | Solyc02g014220 | 2 | 15,089,049/15,093,042 | 3993 | 2127 | 48 | 180 | 633 | 7.6 | 69.8 | C | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-4 | Solyc02G002026 | Solyc02g083980 | 2 | 47,539,277/47,542,107 | 2830 | 1605 | 0 | 0 | 535 * | 5.5 * | 59.2 * | A | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-5 | Solyc03G001799 | Solyc03g083820 | 3 | 49,794,157/49,796,385 | 2228 | 1497 | 0 | 0 | 499 | 8.4 | 55.4 | B | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-6 | Solyc04G002891 | Solyc04g081300 | 4 | 66,400,254/66,405,738 | 5484 | 2101 | 300 | 241 | 520 | 5.6 | 56.6 | A | Cell membrane |

| SlGH9-7 | Solyc05G000008 | Solyc05g005080 | 5 | 144,494/147,193 | 2699 | 2231 | 136 | 244 | 617 | 8.9 | 68.3 | A | Cell membrane |

| SlGH9-8 | Solyc05G002376 | Solyc05g052530 | 5 | 62,595,709/62,607,754 | 12045 | 2759 | 0 | 140 | 873 * | 7.9 * | 99.4 * | A | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-9 | Solyc06G001635 | Solyc06g066120 | 6 | 43,899,874/43,903,182 | 3308 | 1944 | 110 | 373 | 487 | 8.5 | 54.1 | B | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-10 | Solyc07G001834 | Solyc07g049300 | 7 | 59,881,351/59,885,115 | 3764 | 1862 | 146 | 204 | 504 | 6.02 | 57.0 | B | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-11 | Solyc07G002653 | Solyc07g064870 | 7 | 67,299,221/67,303,837 | 4616 | 1602 | 0 | 0 | 534 | 8.7 | 60.9 | B | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-12 | Solyc08G002413 | Solyc08g081620 | 8 | 66,255,855/66,259,192 | 3337 | 1578 | 72 | 0 | 502 | 7.5 | 55.2 | B | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-13 | Solyc08G002479 | Solyc08g082250 | 8 | 66,732,363/66,737,321 | 4958 | 2196 | 194 | 124 | 626 | 9.3 | 68.9 | C | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-14 | Solyc08G002569 | Solyc08g083210 | 8 | 67,444,966/67,447,305 | 2339 | 1970 | 225 | 251 | 498 | 6 | 54.4 | B | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-15 | Solyc09G000424 | Solyc09g010210 | 9 | 3,689,632/3,694,758 | 5126 | 1606 | 73 | 63 | 490 | 8.4 | 54.1 | B | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-16 | Solyc09G002275 | Solyc09g075360 | 9 | 63,989,601/63,992,815 | 3214 | 1732 | 72 | 127 | 511 | 9.05 | 56.2 * | B | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

| SlGH9-17 | Solyc11G000365 | Solyc11g008820 | 11 | 3,075,800/3,082,697 | 6897 | 2118 | 39 | 171 | 636 * | 9.1 * | 71.3 * | A | Cell membrane |

| SlGH9-18 | Solyc11G001671 | Solyc11g040340 | 11 | 40,371,634/40,373,802 | 2168 | 1440 | 0 | 0 | 480 | 8.7 | 53.4 | B | Cell wall |

| SlGH9-19 | Solyc12G002184 | Solyc12g055970 | 12 | 62,863,919/62,868,221 | 4302 | 2209 | 27 | 328 | 618 * | 6.3 * | 68.3 * | C | Cell membrane/Cell wall |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bojórquez-Armenta, Y.d.J.; Sarmiento-López, L.G.; Pozo, M.J.; Castro-Martínez, C.; Lopez-Meyer, M. Characterization of Endoglucanase (GH9) Gene Family in Tomato and Its Expression in Response to Rhizophagus irregularis and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plants 2025, 14, 3458. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223458

Bojórquez-Armenta YdJ, Sarmiento-López LG, Pozo MJ, Castro-Martínez C, Lopez-Meyer M. Characterization of Endoglucanase (GH9) Gene Family in Tomato and Its Expression in Response to Rhizophagus irregularis and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plants. 2025; 14(22):3458. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223458

Chicago/Turabian StyleBojórquez-Armenta, Yolani de Jesús, Luis Gerardo Sarmiento-López, María J. Pozo, Claudia Castro-Martínez, and Melina Lopez-Meyer. 2025. "Characterization of Endoglucanase (GH9) Gene Family in Tomato and Its Expression in Response to Rhizophagus irregularis and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum" Plants 14, no. 22: 3458. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223458

APA StyleBojórquez-Armenta, Y. d. J., Sarmiento-López, L. G., Pozo, M. J., Castro-Martínez, C., & Lopez-Meyer, M. (2025). Characterization of Endoglucanase (GH9) Gene Family in Tomato and Its Expression in Response to Rhizophagus irregularis and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plants, 14(22), 3458. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223458