Interactive Effects of Firebreak Construction and Elevation on Species Diversity in Subtropical Montane Shrubby Grasslands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

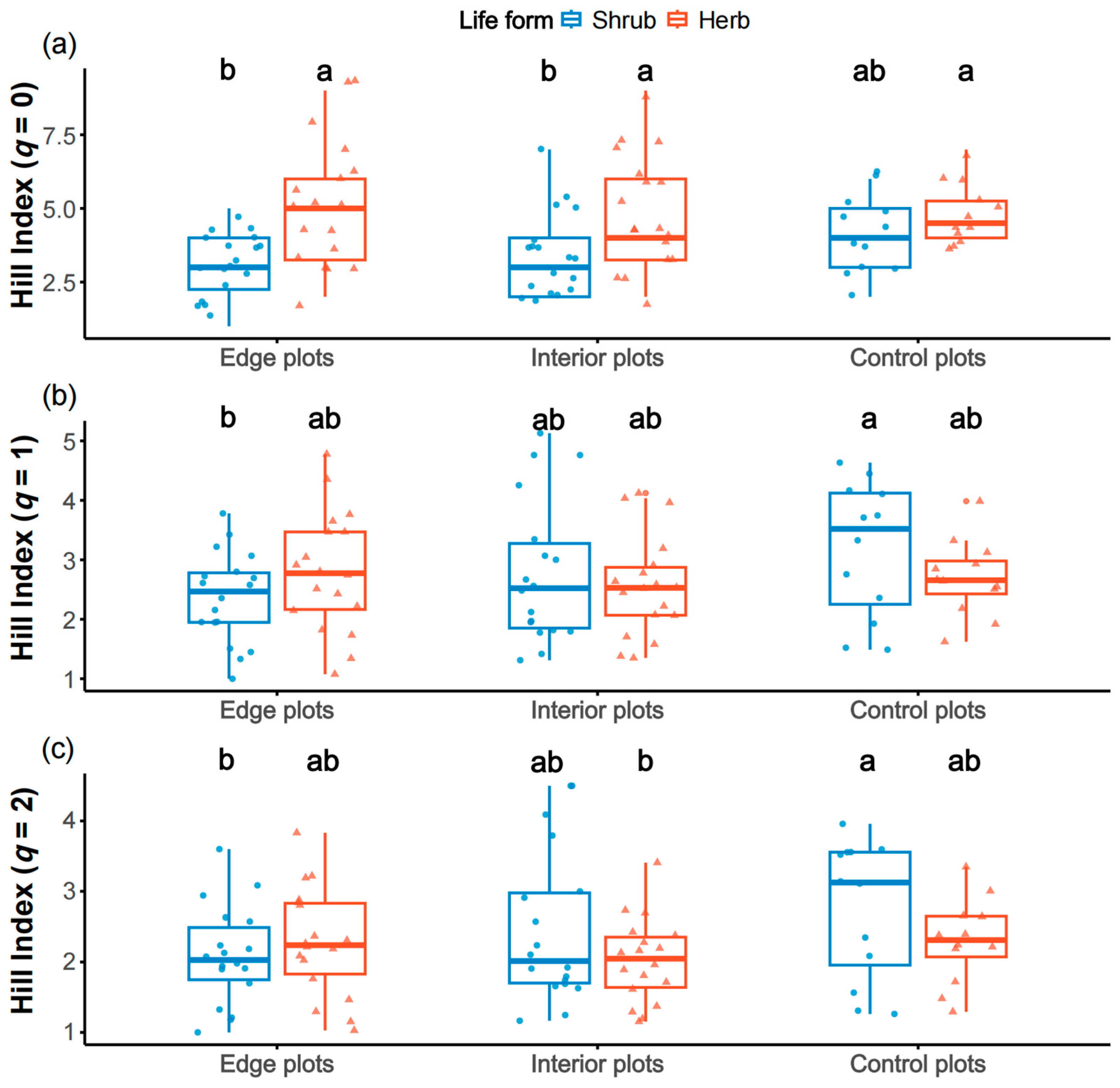

2.1. The Difference in Species Diversity Among Plots

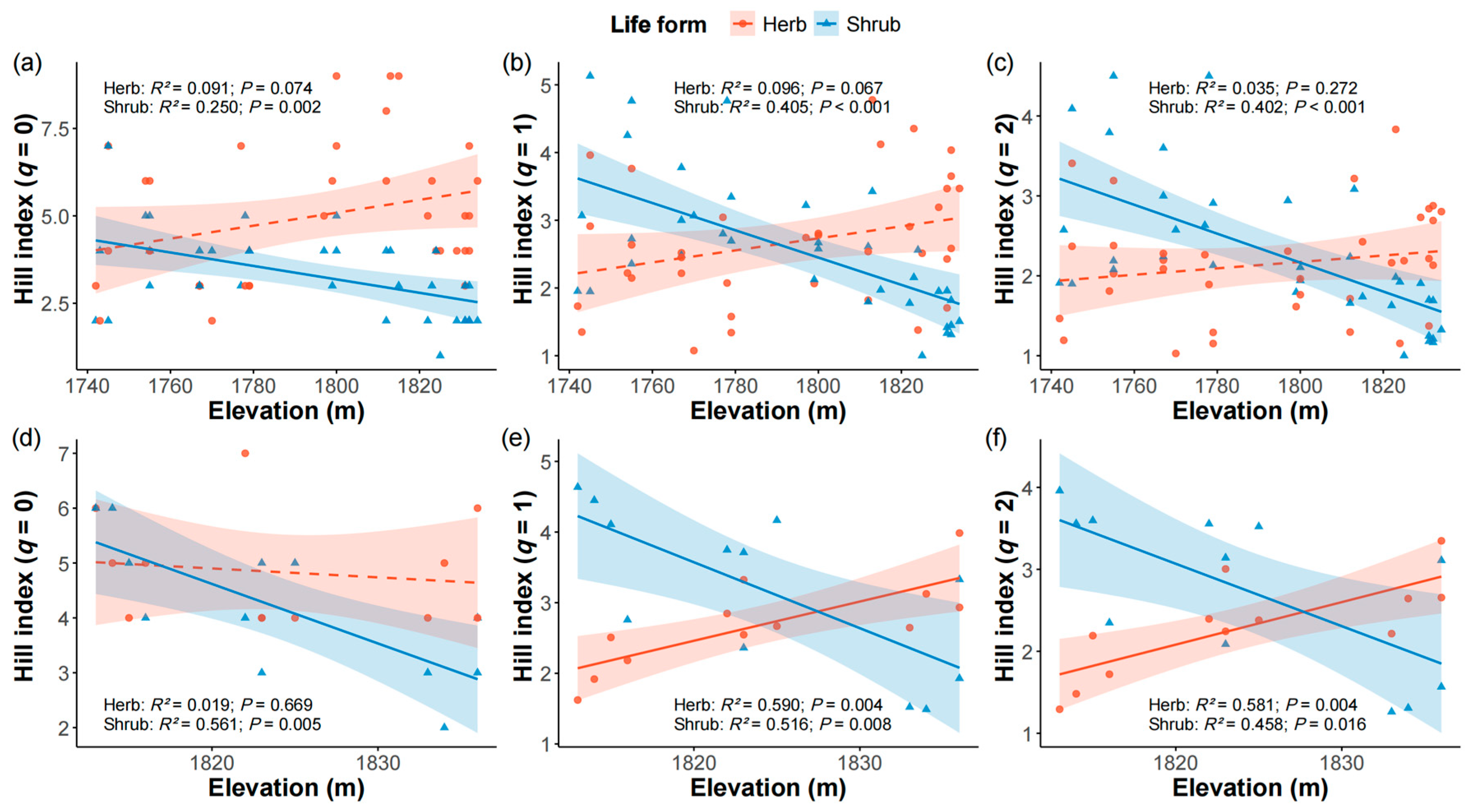

2.2. Species Diversity Responses to Elevation Across Firebreak and Control Areas

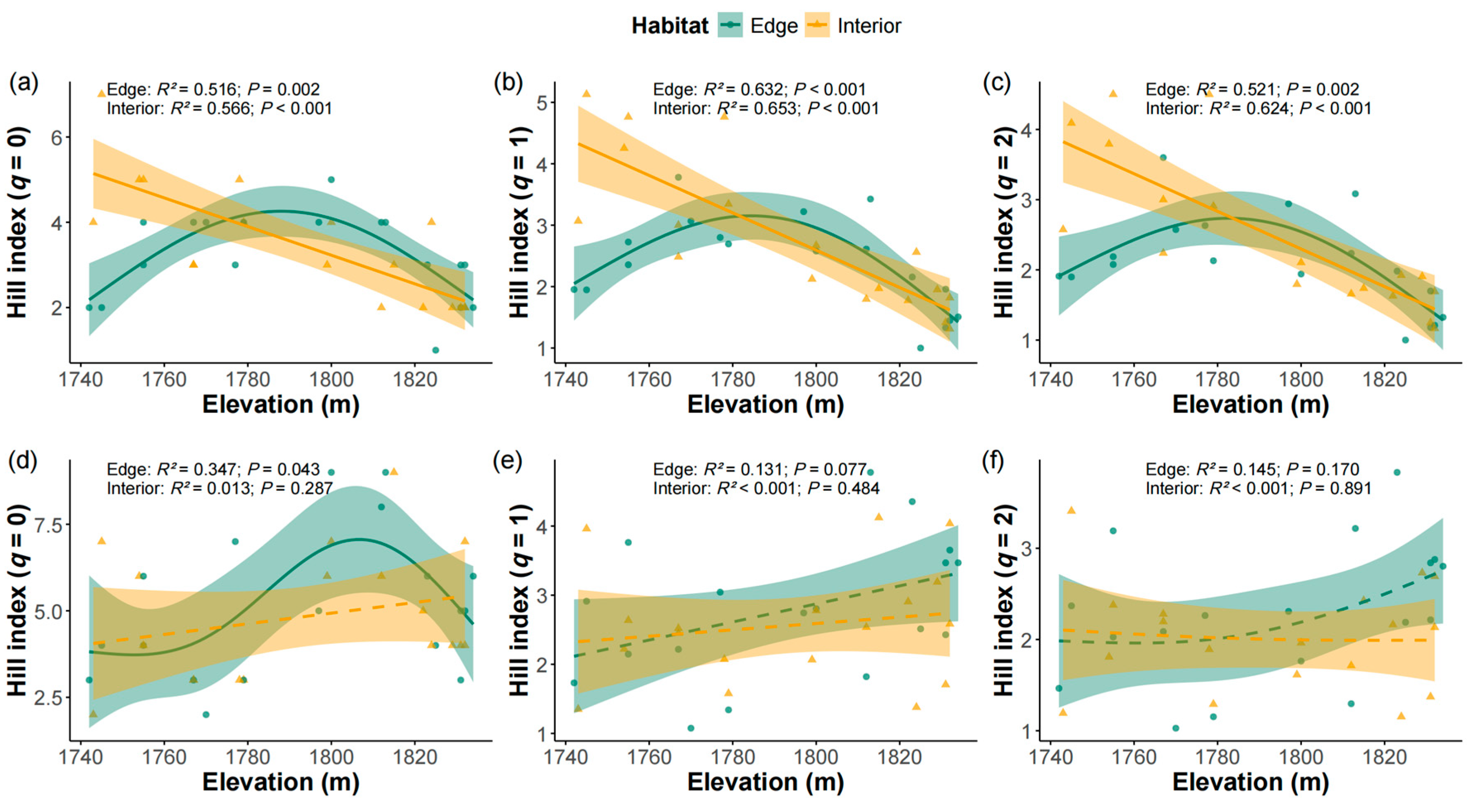

2.3. Species Diversity Responses to Elevation Across Edge and Interior Plots

2.4. Effects of Environmental Factors on Species Diversity

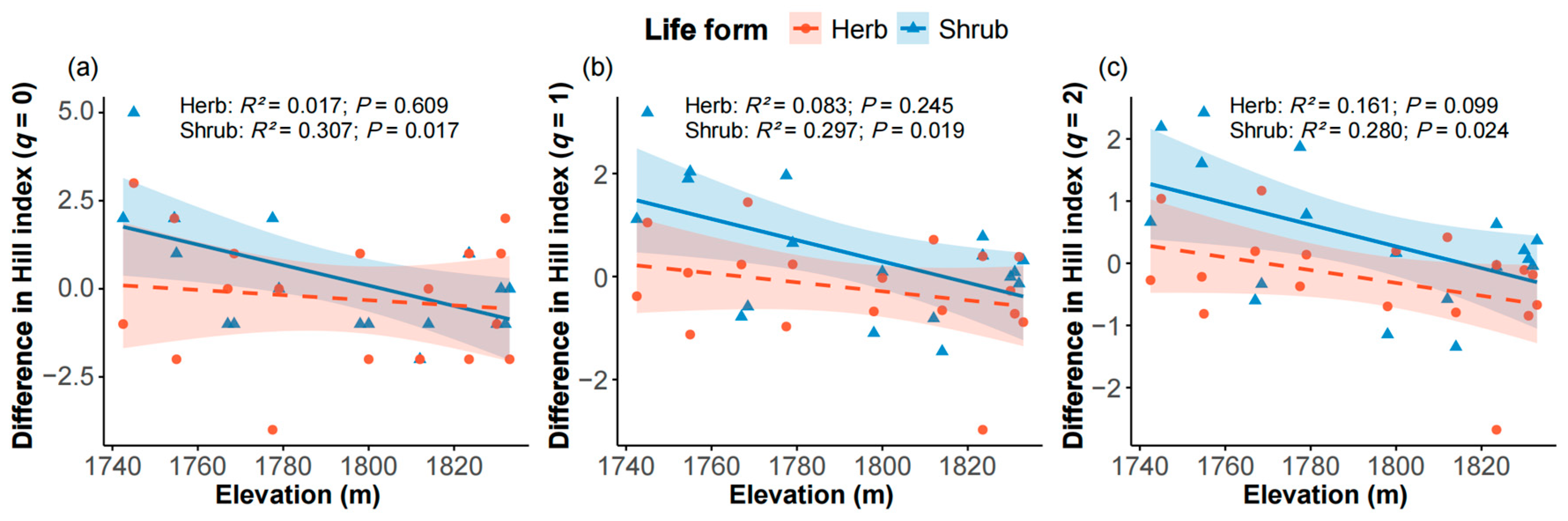

2.5. Diversity Differences of Edge and Interior Plots Along Elevation

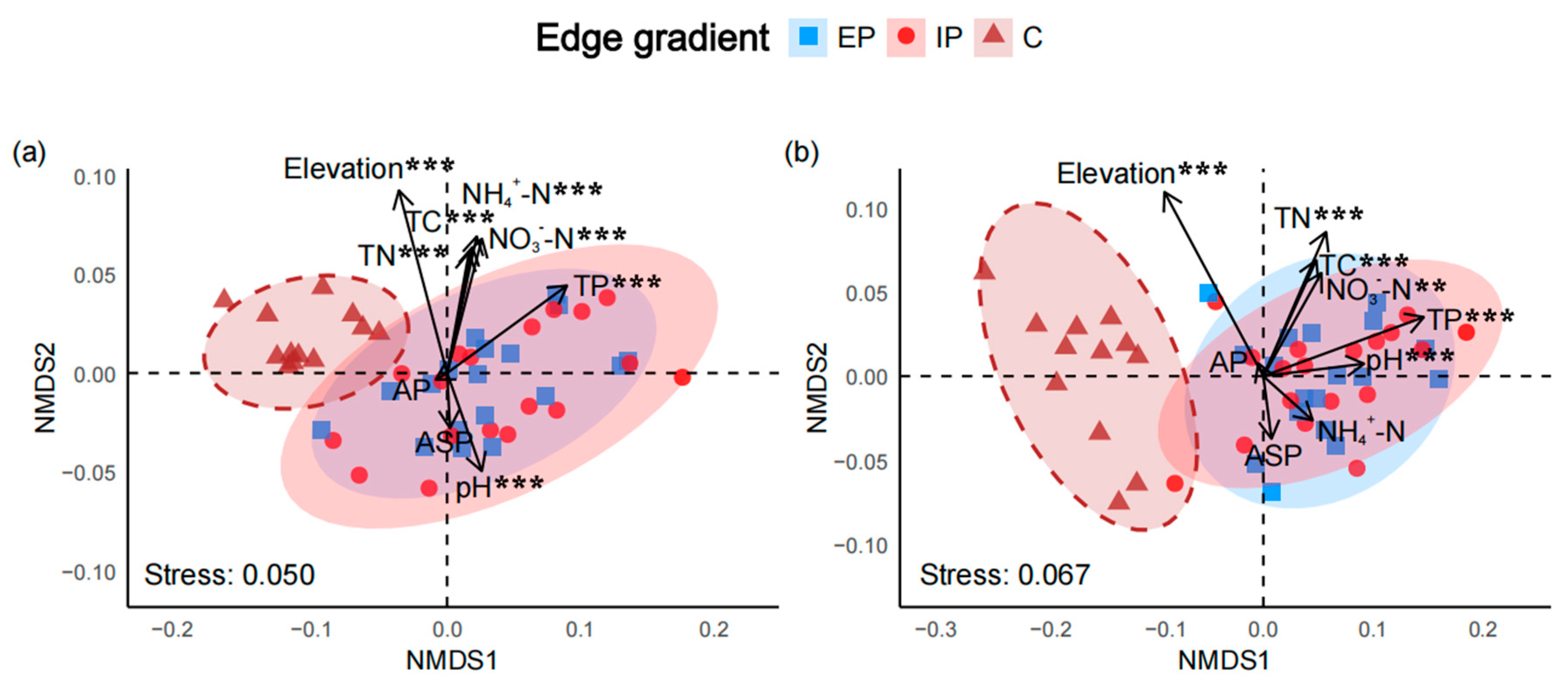

2.6. Species Composition and Environmental Drivers

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Site

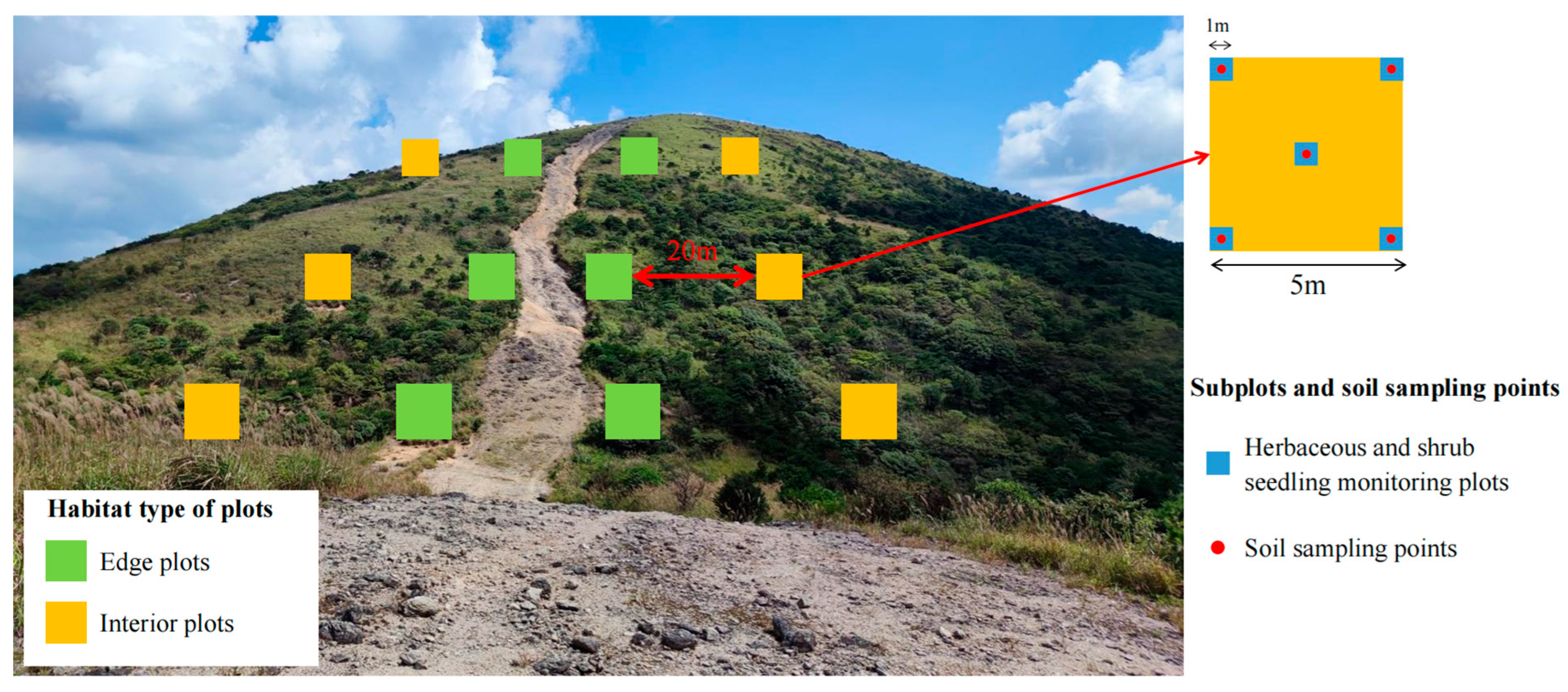

4.2. Study Design and Plant Community Survey

4.3. Environmental Factor Survey

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brandt, J.S.; Haynes, M.A.; Kuemmerle, T.; Waller, D.M.; Radeloff, V.C. Regime shift on the roof of the world: Alpine meadows converting to shrublands in the southern Himalayas. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 158, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiano, K.; Clerici, N.; Norden, N.; Etter, A. Secondary forest and shrubland dynamics in a highly transformed landscape in the Northern Andes of Colombia (1985–2015). Forests 2017, 8, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehnder, T.; Lüscher, A.; Ritzmann, C.; Pauler, C.M.; Berard, J.; Kreuzer, M.; Schneider, M.K. Dominant shrub species are a strong predictor of plant species diversity along subalpine pasture-shrub transects. Alp. Bot. 2020, 130, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C.; Kèorner, C. Alpine Plant Life: Functional Plant Ecology of High Mountain Ecosystems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rahbek, C.; Borregaard, M.K.; Colwell, R.K.; Dalsgaard, B.; Holt, B.G.; Morueta-Holme, N.; Nogues-Bravo, D.; Whittaker, R.J.; Fjeldså, J. Humboldt’s enigma: What causes global patterns of mountain biodiversity? Science 2019, 365, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.H.; Wang, W.Z.; Zhu, W.Z.; Zhang, P.P.; Chang, R.Y.; Wang, G.X. Shrub ecosystem structure in response to anthropogenic climate change: A global synthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 953, 176202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiane, K.K.; Ramoelo, A.; Adelebu, S.; Daemane, E. Assessing environmental factors contributing to plant species richness in mountainous mesic grasslands. Koedoe 2023, 65, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debinski, D.M.; Jakubauskas, M.E.; Kindscher, K. Montane meadows as indicators of environmental change. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2000, 64, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, M.; Pauli, H.; Futschik, A.; Akhalkatsi, M.; Barančok, P.; Benito Alonso, J.L.; Coldea, G.; Dick, J.; Erschbamer, B.; Fernández Calzado, M.a.R.; et al. Continent-wide response of mountain vegetation to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauchard, A.; Kueffer, C.; Dietz, H.; Daehler, C.C.; Alexander, J.; Edwards, P.J.; Arévalo, J.R.; Cavieres, L.A.; Guisan, A.; Haider, S.; et al. Ain’t no mountain high enough: Plant invasions reaching new elevations. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.B. Rangeland degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau: A review of the evidence of its magnitude and causes. J. Arid. Environ. 2010, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux-Fouillet, P.; Wipf, S.; Rixen, C. Long-term impacts of ski piste management on alpine vegetation and soils. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; Purvis, A.; Verburg, P.H.; Obura, D.; Leadley, P.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; De Meester, L.; Dulloo, E.; Martín-López, B.; et al. Set ambitious goals for biodiversity and sustainability. Science 2020, 370, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascoli, D.; Russo, L.; Giannino, F.; Siettos, C.; Moreira, F. Firebreak and fuelbreak. In Encyclopedia of Wildfires and Wildland-Urban Interface Fires; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, P.; Rodriguez, A.; Gutierrez, D.; Jordano, D.; Fernandez-Haeger, J. Firebreaks as a barrier to movement: The case of a butterfly in a Mediterranean landscape. J. Insect Conserv. 2019, 23, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.L.; Alam, M.A.; Perry, G.L.W.; Paterson, A.M.; Wyse, S.V.; Curran, T.J. Green firebreaks as a management tool for wildfires: Lessons from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, T.G.; Uys, R.G.; Mills, A.J. Ecological effects of fire-breaks in the montane grasslands of the southern Drakensberg, South Africa. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2004, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachinger, L.M.; Brown, L.R.; van Rooyen, M.W. The effects of fire-breaks on plant diversity and species composition in the grasslands of the Loskop Dam Nature Reserve, South Africa. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2016, 33, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.E.; Hovenden, M.J.; Neyland, M.G.; Mitchell, S.J.; Adams, P.R.; Wood, M.J. Short-term effects of firebreaks on seedling growth, nutrient concentrations and soil strength in southern Australian wet eucalypt forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 278, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipel, T.; Rew, L.J.; Taylor, K.T.; Maxwell, B.D.; Lehnhoff, E.A.; Jiménez-Alfaro, B. Disturbance type influences plant community resilience and resistance to Bromus tectorum invasion in the sagebrush steppe. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2018, 21, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenius, L.; Roberge, J.-M.; Månsson, J.; Ericsson, G. Ungulate-adapted forest management: Effects of slash treatment at harvest on forage availability and use. Eur. J. For. Res. 2013, 133, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charco, J.; Perea, R.; Gil, L.; Nanos, N. Impact of deer rubbing on pine forests: Implications for conservation and management of Pinus pinaster populations. Eur. J. For. Res. 2016, 135, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhong, M.J.; Zhang, J.; Si, X.F.; Yang, S.N.; Jiang, J.P.; Hu, J.H. Multidimensional amphibian diversity and community structure along a 2 600 m elevational gradient on the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Zool. Res. 2022, 43, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grytnes, J.A.; Vetaas, O.R. Species richness and altitude: A comparison between null models and interpolated plant species richness along the Himalayan altitudinal gradient, Nepal. Am. Nat. 2002, 159, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, A.; Körner, C.; Brun, J.-J.; Guisan, A.; Tappeiner, U. Ecological and Land Use Studies Along Elevational Gradients. Mt. Res. Dev. 2007, 27, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Uniyal, S.K.; Batish, D.R.; Singh, H.P.; Jaryan, V.; Rathee, S.; Sharma, P.; Kohli, R.K. Patterns of plant communities along vertical gradient in Dhauladhar Mountains in Lesser Himalayas in North-Western India. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 136919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzad, H.M.; Jiang, Y.J.; Arif, M.; Wu, C.; He, Q.F.; Zhao, H.J.; Lv, T. Tunneling-induced groundwater depletion limits long-term growth dynamics of forest trees. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. The use of ‘altitude’ in ecological research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, B. Divergent tree radial growth at alpine coniferous forest ecotone and corresponding responses to climate change in northwestern China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist, M.K.; Sanders, N.J.; Wardle, D.A. Community and Ecosystem Responses to Elevational Gradients: Processes, Mechanisms, and Insights for Global Change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013, 44, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. Individuals have limitations, not communities—A response to Marrs, Weiher and Lortie et al. J. Veg. Sci. 2004, 15, 581–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odland, A.; Birks, H. The altitudinal gradient of vascular plant richness in Aurland, western Norway. Ecography 1999, 22, 548–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, P.; Deka, J.; Bharali, S.; Kumar, A.; Tripathi, O.P.; Singha, L.B.; Dayanandan, S.; Khan, M.L. Plant diversity patterns and conservation status of eastern Himalayan forests in Arunachal Pradesh, Northeast India. For. Ecosyst. 2017, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shooner, S.; Davies, T.J.; Saikia, P.; Deka, J.; Bharali, S.; Tripathi, O.P.; Singha, L.; Latif Khan, M.; Dayanandan, S. Phylogenetic diversity patterns in Himalayan forests reveal evidence for environmental filtering of distinct lineages. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Z. Ordination and classification of vegetation along an altitudinal gradient in the Venezuelan páramos. Vegetatio 1984, 55, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrehiwot, K.; Demissew, S.; Woldu, Z.; Fekadu, M.; Desalegn, T.; Teferi, E. Elevational changes in vascular plants richness, diversity, and distribution pattern in Abune Yosef mountain range, Northern Ethiopia. Plant Divers. 2019, 41, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Behera, M.D.; Das, A.P.; Panda, R.M. Plant richness pattern in an elevation gradient in the Eastern Himalaya. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 2085–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Su, J.; Zhao, X. Response relationship between plant community diversity and altitude in Qilian Mountain National Nature Reserve, Gansu Province. Nat. Prot. Areas 2024, 4, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, N.B.; Urban, D.L.; White, P.S.; Moody, A.; Klein, R.N. Vegetation dynamics vary across topographic and fire severity gradients following prescribed burning in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 365, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aardt, A.C.; de Jager, J.C.L.; van Tol, J.J. Firebreaks and Their Effect on Vegetation Composition and Diversity in Grasslands of Golden Gate Highlands National Park, South Africa. Diversity 2024, 16, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, L.E.; Burns, N.R.; Woodin, S.J. Slow recovery of High Arctic heath communities from nitrogen enrichment. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remy, E.; Wuyts, K.; Boeckx, P.; Ginzburg, S.; Gundersen, P.; Demey, A.; Van Den Bulcke, J.; Van Acker, J.; Verheyen, K. Strong gradients in nitrogen and carbon stocks at temperate forest edges. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 376, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlack, G.R. Microenvironment variation within and among forest edge sites in the eastern United States. Biol. Conserv. 1993, 66, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, A.; Pickering, C.M. Testing the capacity of clothing to act as a vector for non-native seed in protected areas. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von der Lippe, M.; Kowarik, I. Long-distance dispersal of plants by vehicles as a driver of plant invasions. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Pickering, C.M.; Xu, L.; Lin, X. Tourist vehicle as a selective mechanism for plant dispersal: Evidence from a national park in the eastern Himalaya. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 285, 112109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, P.; Laffan, M.; Lewis, R.; Churchill, K. Impact of major snig tracks on the productivity of wet eucalypt forest in Tasmania measured 17–23 years after harvesting. Aust. For. 2004, 67, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, A.; Wood, M.; James, R. Soil protection with logging residues during mechanised harvesting of native forests in Tasmania: A preliminary study. Aust. For. 2006, 69, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Hulin, F.; Chevalier, R.; Archaux, F.; Gosselin, F. Is plant diversity on tractor trails more influenced by disturbance than by soil characteristics? For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 379, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, T.; McCune, J.L. Vegetation type and trail use interact to affect the magnitude and extent of recreational trail impacts on plant communities. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesson, P.; Huntly, N. The roles of harsh and fluctuating conditions in the dynamics of ecological communities. Am. Nat. 1997, 150, 519–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.P.; Marshall, D.J. Environmental stress, facilitation, competition, and coexistence. Ecology 2013, 94, 2719–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violle, C.; Pu, Z.; Jiang, L. Experimental demonstration of the importance of competition under disturbance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12925–12929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illuminati, A.; Matesanz, S.; Pías, B.; Sánchez, A.M.; de la Cruz, M.; Ramos-Muñoz, M.; López-Angulo, J.; Pescador, D.S.; Escudero, A. Functional differences between herbs and woody species in a semiarid Mediterranean plant community: A whole-plant perspective on growth, nutrient-use and size. Funct. Ecol. 2025, 39, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.K.; Chettri, B.; Vijayan, L. Distribution pattern of trees along an elevation gradient of Eastern Himalaya, India. Acta Oecologica 2011, 37, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, P.; Akhani, H.; Van der Maarel, E. Species diversity and life-form patterns in steppe vegetation along a 3000 m altitudinal gradient in the Alborz Mountains, Iran. Folia Geobot. 2013, 48, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.H. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs: High diversity of trees and corals is maintained only in a nonequilibrium state. Science 1978, 199, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Detto, M.; Fang, S.; Li, Y.; Zang, R.; Liu, S.; Nardoto, G.B. Habitat hotspots of common and rare tropical species along climatic and edaphic gradients. J. Ecol. 2015, 103, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamelink, G.W.W.; Goedhart, P.W.; Frissel, J.Y. Why Some Plant Species Are Rare. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, J.; Miller, J.E.D.; Steel, Z.L.; Batzer, E.E.; Safford, H.D. High-severity fire drives persistent floristic homogenization in human-altered forests. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnoor, T.; Bruun, H.H.; Olsson, P.A. Soil Disturbance as a Grassland Restoration Measure-Effects on Plant Species Composition and Plant Functional Traits. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, W.; Long, D.; Yang, Z.; Mao, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, S.; Pan, X.; Liu, J.; et al. α and β diversity patterns of woody plant communities along an elevation gradient in Baishanzu National Park. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 7700–7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yao, J.; Lin, Y.; Wu, S.; Yang, Z.; Jin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Shen, G.; et al. Bias in Discontinuous Elevational Transects for Tracking Species Range Shifts. Plants 2025, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Ding, B.; Zheng, C.; Ye, Z.; Chen, X. The floristic analysis of seed plants in Baishanzu Nature Reserve from Zhejiang Province. Acta Bot. Yunnanica 2004, 26, 605–618. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Vellend, M.; Wang, Z.; Yu, M. High beta diversity among small islands is due to environmental heterogeneity rather than ecological drift. J. Biogeogr. 2018, 45, 2252–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotta, C.; Feoli, E. Hill numbers everywhere. Does it make ecological sense? Ecol. Indic. 2024, 161, 111971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.O. Diversity and Evenness: A Unifying Notation and Its Consequences. Ecology 1973, 54, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H. A diversity of beta diversities: Straightening up a concept gone awry. Part 2. Quantifying beta diversity and related phenomena. Ecography 2010, 33, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, L. Partitioning diversity into independent alpha and beta components. Ecology 2007, 88, 2427–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. hillR: Taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic diversity and similarity through Hill Numbers. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.K.; Reeve, R.; Paul, N.K.; Matthiopoulos, J.; Essl, F. Modelling spatial biodiversity in the world’s largest mangrove ecosystem—The Bangladesh Sundarbans: A baseline for conservation. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghoe, M.W.; Marschner, I.C. Flexible regression models for rate differences, risk differences and relative risks. Int. J. Biostat. 2015, 11, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grueber, C.E.; Nakagawa, S.; Laws, R.J.; Jamieson, I.G. Multimodel inference in ecology and evolution: Challenges and solutions. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 24, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bagousse-Pinguet, Y.; Gross, N.; Maestre, F.T.; Maire, V.; de Bello, F.; Fonseca, C.R.; Kattge, J.; Valencia, E.; Leps, J.; Liancourt, P. Testing the environmental filtering concept in global drylands. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hill Index | Environmental Factors | Estimate | p | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edge plots | |||||

| Shrubs | q = 0 | Elevation | −0.012 | 0.042 | 0.622 |

| pH | 6.224 | <0.001 | 0.622 | ||

| q = 1 | Elevation | −0.014 | 0.002 | 0.645 | |

| pH | 4.020 | <0.001 | 0.645 | ||

| q = 2 | Elevation | −0.013 | 0.003 | 0.571 | |

| pH | 3.263 | 0.003 | 0.571 | ||

| Herbs | q = 0 | Elevation | −0.028 | 0.034 | 0.785 |

| pH | 10.693 | <0.001 | 0.785 | ||

| TC | 1.538 | <0.001 | 0.785 | ||

| TP | −0.011 | 0.004 | 0.785 | ||

| q = 1 | Elevation | 0.013 | 0.077 | 0.183 | |

| q = 2 | Elevation | 0.009 | 0.110 | 0.152 | |

| Interior plots | |||||

| Shrubs | q = 0 | Elevation | −0.034 | <0.001 | 0.592 |

| q = 1 | Elevation | −0.030 | <0.001 | 0.673 | |

| q = 2 | Elevation | −0.027 | <0.001 | 0.646 | |

| Herbs | q = 0 | pH | 7.832 | 0.019 | 0.298 |

| q = 1 | None | ||||

| q = 2 | None | ||||

| Control plots | |||||

| Shrubs | q = 0 | Elevation | −0.109 | 0.005 | 0.561 |

| q = 1 | Elevation | −0.093 | 0.008 | 0.516 | |

| q = 2 | Elevation | −0.076 | 0.016 | 0.458 | |

| Herbs | q = 0 | None | |||

| q = 1 | AP | 0.229 | 0.002 | 0.790 | |

| NH4+-N | −0.089 | <0.001 | 0.790 | ||

| q = 2 | AP | 0.154 | 0.001 | 0.958 | |

| NH4+-N | −0.108 | <0.001 | 0.958 | ||

| TC | 0.207 | 0.013 | 0.958 | ||

| TP | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.958 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hui, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shui, Z.; Wu, H.; Cai, Q.; Zhou, W.; Han, W.; Yu, M.; Liu, J. Interactive Effects of Firebreak Construction and Elevation on Species Diversity in Subtropical Montane Shrubby Grasslands. Plants 2025, 14, 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223456

Hui C, Wu Y, Liu Q, Shui Z, Wu H, Cai Q, Zhou W, Han W, Yu M, Liu J. Interactive Effects of Firebreak Construction and Elevation on Species Diversity in Subtropical Montane Shrubby Grasslands. Plants. 2025; 14(22):3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223456

Chicago/Turabian StyleHui, Chengyang, Yougui Wu, Qishi Liu, Zhangli Shui, Huihui Wu, Qian Cai, Weilong Zhou, Wenjuan Han, Mingjian Yu, and Jinliang Liu. 2025. "Interactive Effects of Firebreak Construction and Elevation on Species Diversity in Subtropical Montane Shrubby Grasslands" Plants 14, no. 22: 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223456

APA StyleHui, C., Wu, Y., Liu, Q., Shui, Z., Wu, H., Cai, Q., Zhou, W., Han, W., Yu, M., & Liu, J. (2025). Interactive Effects of Firebreak Construction and Elevation on Species Diversity in Subtropical Montane Shrubby Grasslands. Plants, 14(22), 3456. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14223456