Beyond Bees: Evidence of Bird Visitation and Putative Pollination in the Golden Lotus (Musella lasiocarpa)—One of the Six Buddhist Flowers—Through Field Surveys and Citizen Science

Abstract

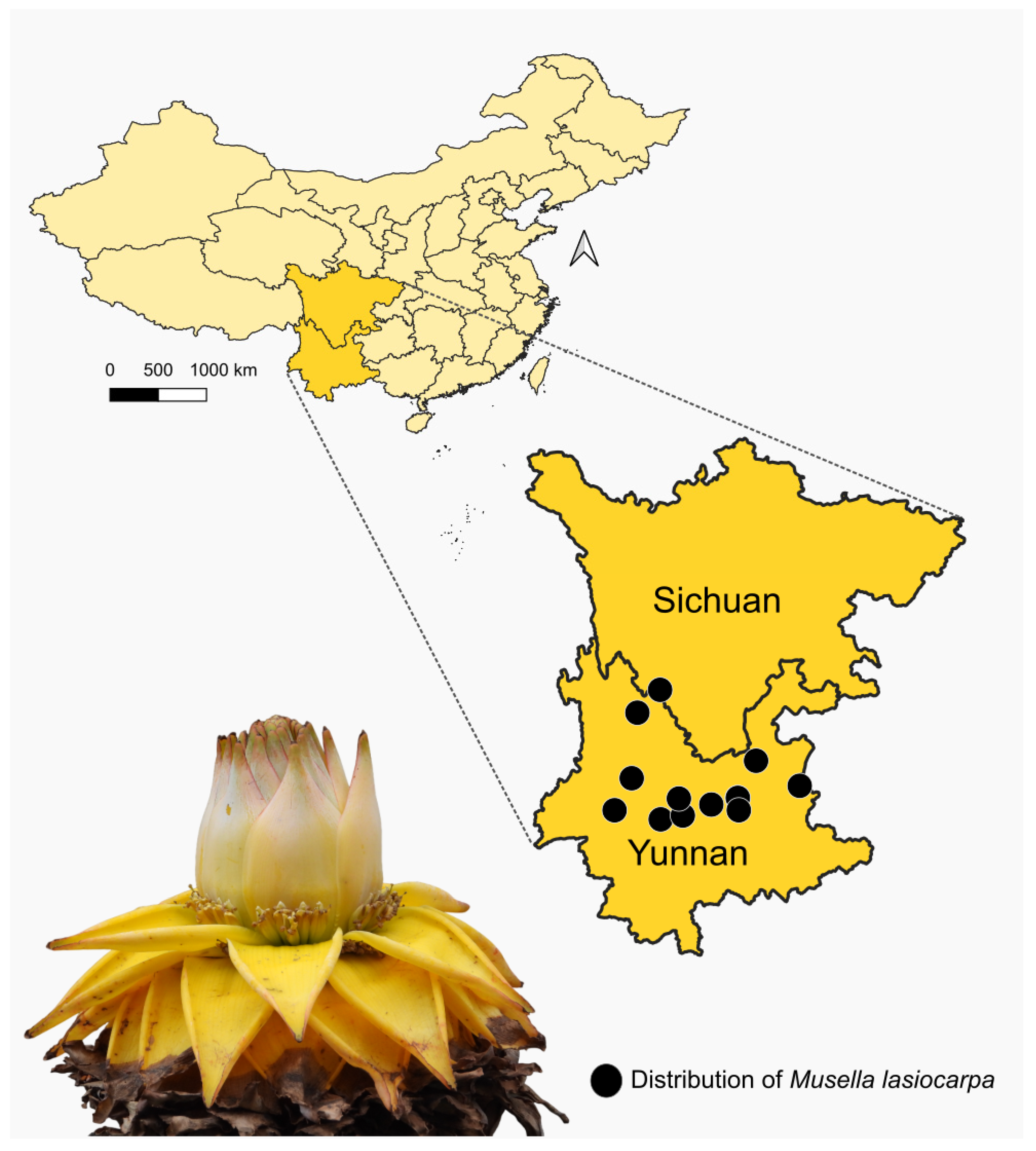

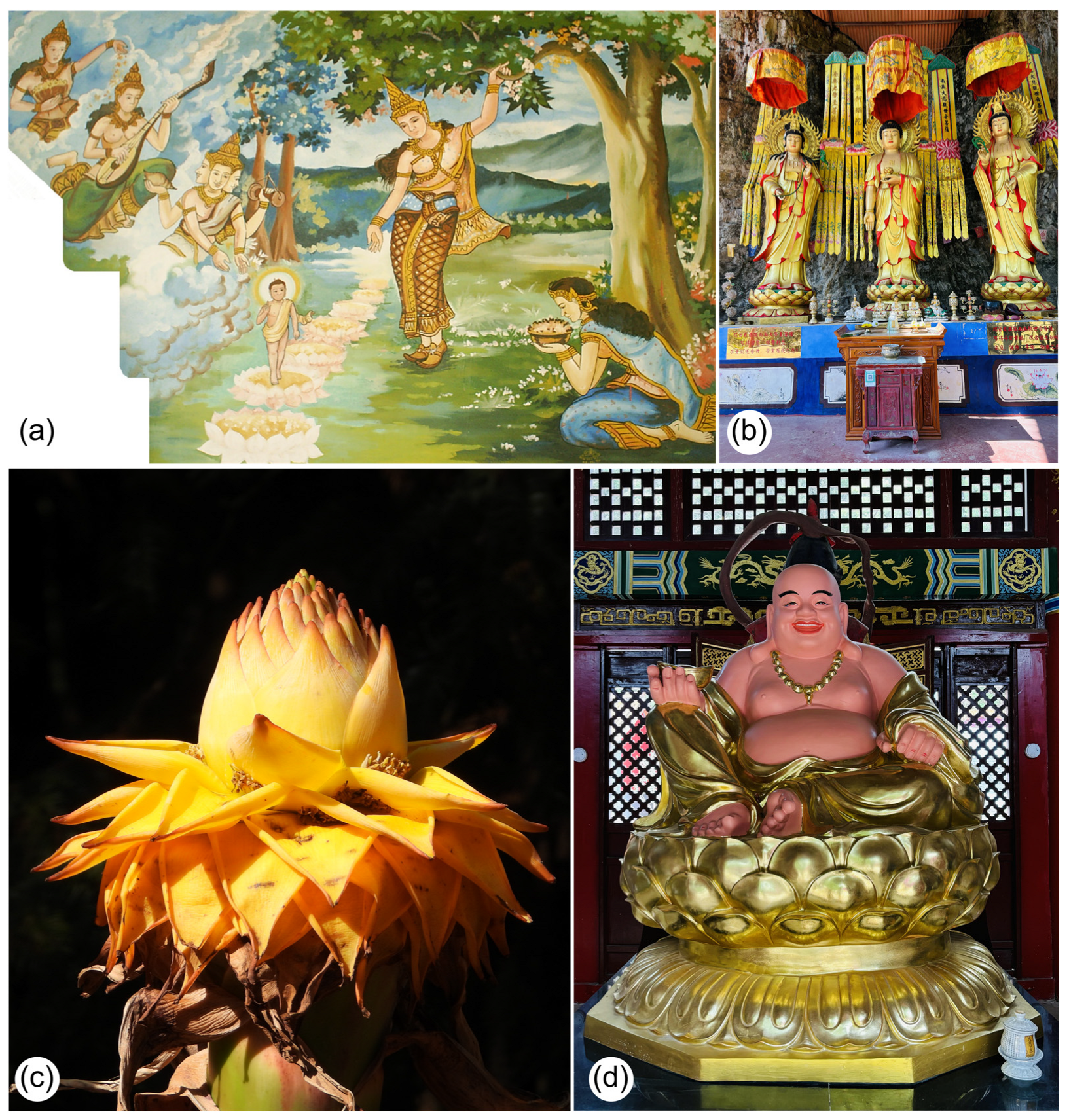

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

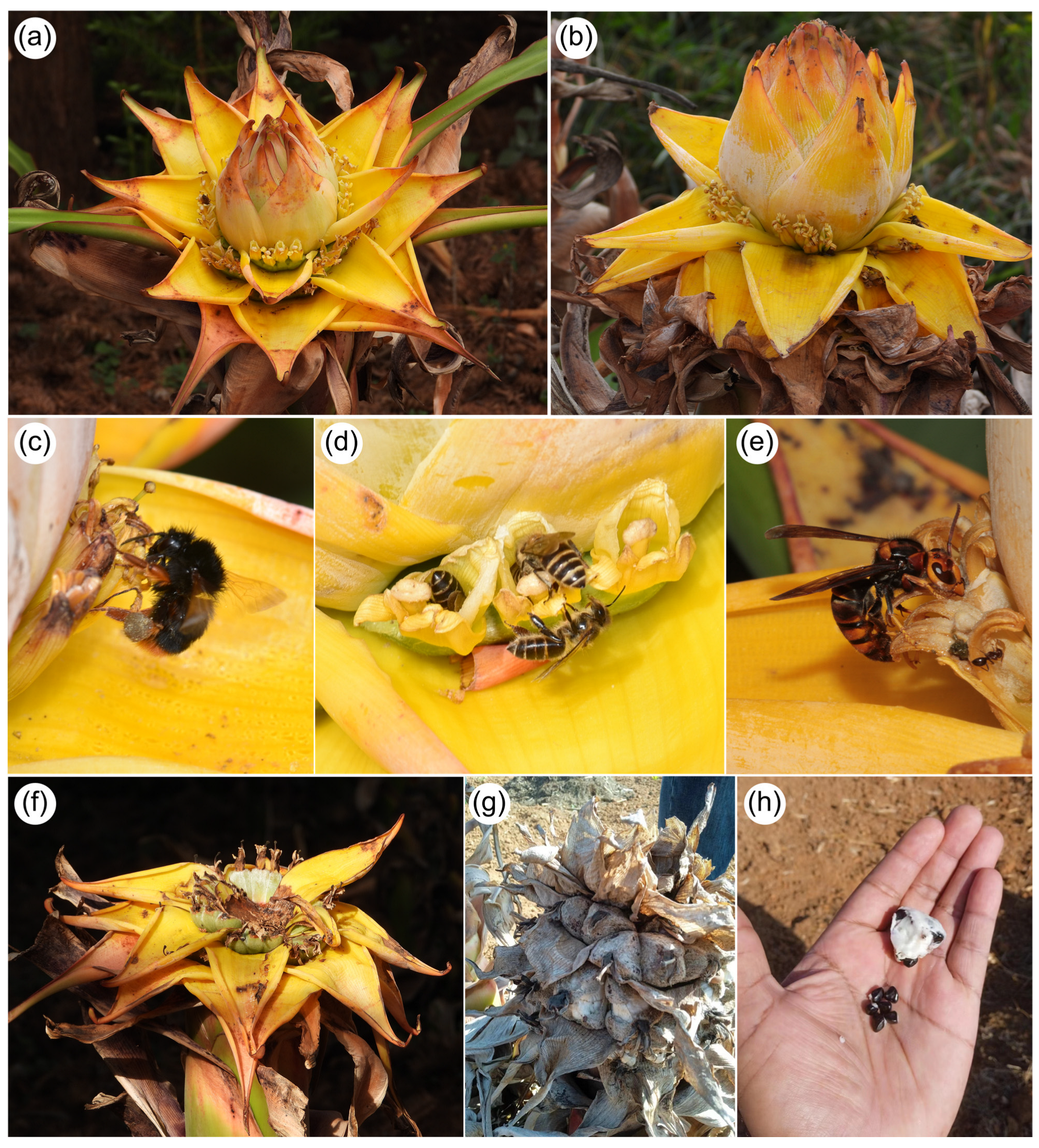

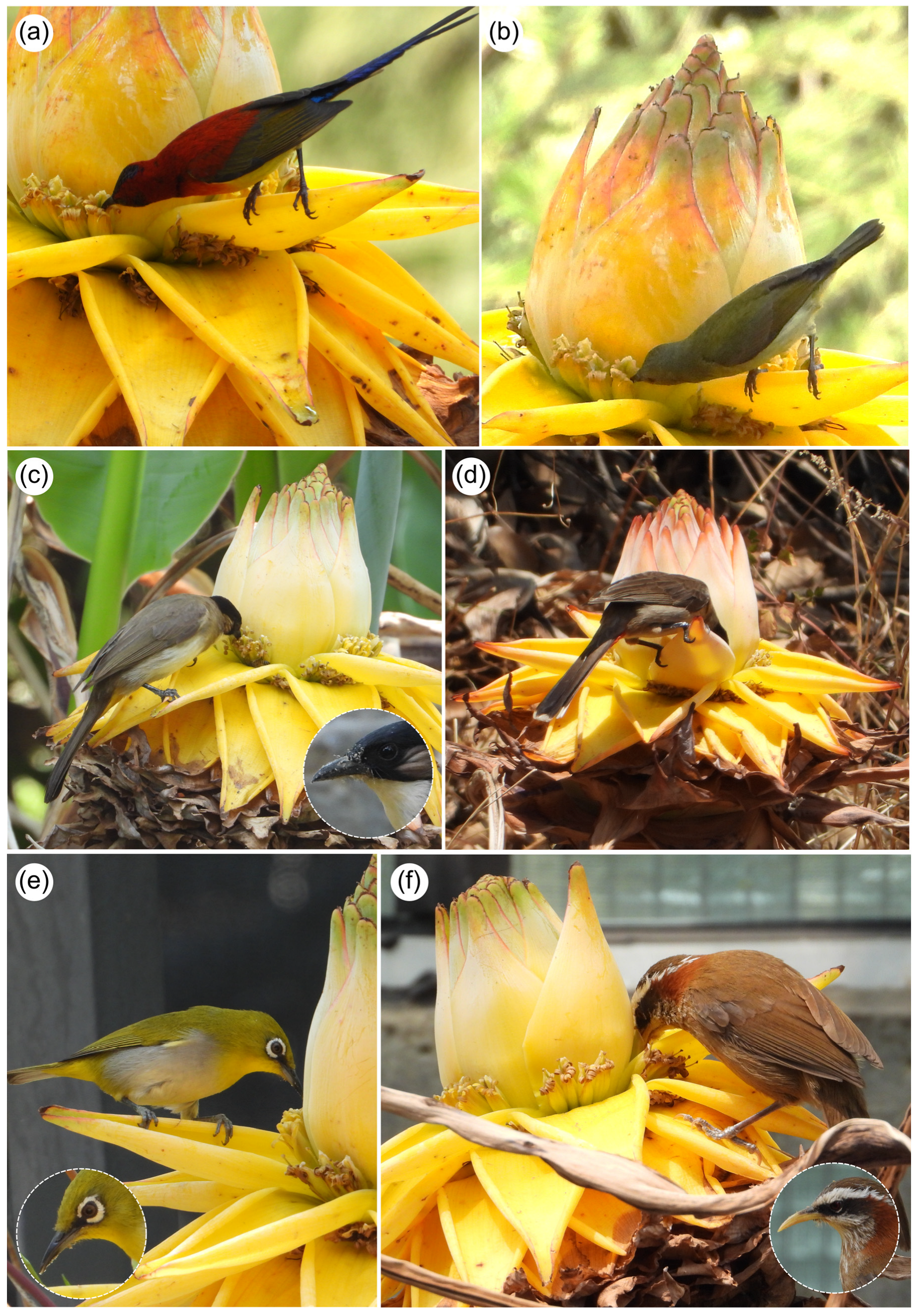

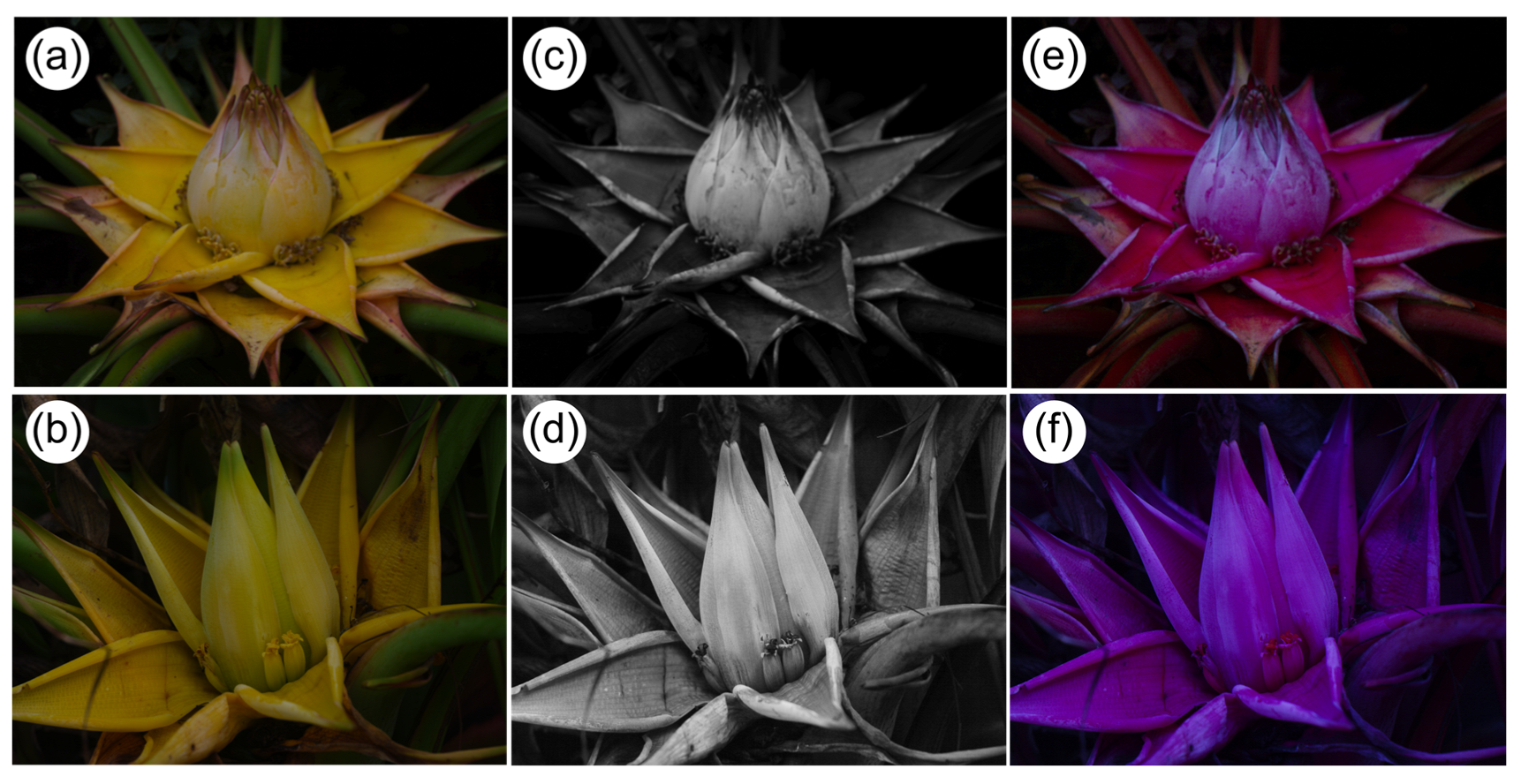

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Evidence of Bird Visitation and Putative Pollination in Golden Lotus

4.2. Golden Lotus as a Key Plant Resource for Animals and Humans

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ollerton, J. Birds and Flowers: An Intimate 50 Million Year Relationship; Pelagic Publishing: Exeter, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, T.H.; Muchhala, N. Nectar-feeding bird and bat niches in two worlds: Pantropical comparisons of vertebrate pollination systems. J. Biogeogr. 2008, 35, 764–780. [Google Scholar]

- Funamoto, D. Plant–pollinator interactions in East Asia: A review. J. Pollinat. Ecol. 2019, 25, 46–68. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, L. Musaceae. In Flowering Plants Monocotyledons: Alismatanae and Commelinanae (Except Gramineae); Kubitzki, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 296–301. [Google Scholar]

- Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Fay, M.F.; Chase, M.W. Plants of the World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Vascular Plants; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Itino, T.; Kato, M.; Hotta, M. Pollination ecology of the two wild bananas, Musa acuminata subsp. halabanensis and M. salaccensis: Chiropterophily and ornithophily. Biotropica 1991, 23, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.-Z.; Kress, W.J.; Wang, H.; Li, D.-Z. Insect pollination of Musella (Musaceae), a monotypic genus endemic to Yunnan, China. Plant Syst. Evol. 2002, 235, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Kress, W.J. Ornithophilous and chiropterophilous pollination in Musa itinerans (Musaceae), a pioneer species in tropical rain forests of Yunnan, southwestern China. Biotropica 2002, 34, 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Nur, N. Studies on pollination in Musaceae. Ann. Bot. 1976, 40, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuram, H.; Singaravelan, N.; Nathan, P.T.; Rajan, K.E.; Marimuthu, G. Foraging ecology of pteropodid bats: Pollination and seed dispersal. In Bats: Biology, Behavior and Conservation; Nathan, P.T., Rajan, K.E., Marimuthu, G., Eds.; Narosa Publishing House: New Delhi, India, 2011; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Endress, P.K. Diversity and Evolutionary Biology of Tropical Flowers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Faegri, K.; van der Pijl, L. The Principles of Pollination Ecology, 3rd ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Z.-X.; Wang, H. Morphological comparison of floral nectaries in Musaceae, with reference to its pollinators. Biodivers. Sci. 2007, 15, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.adhnms (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Wu, D.L.; Kress, W.J. Musaceae. In Flora of China; Wu, C.Y., Raven, P.H., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, China; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2001; Volume 24, pp. 314–318. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.-Z.; Kress, W.J.; Long, C.-L. The ethnobotany of Musella lasiocarpa (Musaceae), an endemic plant of southwest China. Econ. Bot. 2003, 57, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Ahmed, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Long, B.; Yang, C.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, R. Why Musella lasiocarpa (Musaceae) is used in southwest China to feed pigs. Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xin, T.; Long, B. Biodiversity of Chinese ornamentals. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1087, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, N.P.; Brenes, F.V. Flight cage observations of foraging mode in Phyllostomus discolor, P. hastatus, and Glossophaga commissarisi. Biotropica 2001, 33, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.L., Jr.; Surry, D.; Green, A. The use of social media and citizen science to identify, track, and report birds. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 167, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryjanowski, P.; Hetman, M.; Czechowski, P.; Grzywaczewski, G.; Sklenicka, P.; Ziemblińska, K.; Sparks, T.H. Birds drinking alcohol: Species and relationship with people. A review of information from scientific literature and social media. Animals 2020, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, F.; Vizcarra, J.K.; Castillo-Morales, K.; Torres-Zevallos, U.; Cordero-Maldonado, C.; Ampuero-Merino, L.; Herrera-Peralta, K.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; Angulo, F.; Cárdenas-Alayza, S. From social networks to bird enthusiasts: Reporting interactions between plastic waste and birds in Peru. Environ. Conserv. 2023, 50, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H. Birding via Facebook—Methodological considerations when crowdsourcing observations of bird behavior via social media. Birds 2025, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, C.; Ren, Z.-X.; Lunau, K. False-colour photography: A novel digital approach to visualize the bee view of flowers. J. Pollinat. Ecol. 2018, 23, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, G.H.; Ren, Z.X.; Trunschke, J.; Lunau, K.; Wang, H. Salvage of floral resources through re-absorption before flower abscission. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrozo, A.R.; Gomes, L.A.C.; Uieda, W. Feeding behavior and activity period of three Neotropical bat species (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) on Musa paradisiaca inflorescences (Zingiberales: Musaceae). Iheringia Ser. Zool. 2018, 108, e2018011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Chen, J.; Lev-Yadun, S.; Niu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ma, R.; Armbruster, W.S.; Sun, H. Multifunctionality of angiosperm floral bracts: A review. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 1100–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papiorek, S.; Junker, R.R.; Alves-dos-Santos, I.; Melo, G.A.R.; Amaral-Neto, L.P.; Sazima, M.; Wolowski, M.; Freitas, L.; Lunau, K. Bees, birds and yellow flowers: Pollinator-dependent convergent evolution of UV patterns. Plant Biol. 2016, 18, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedinger, N.; Barthlott, W. Untersuchungen zur ultraviolettreflexion von Angiospermenblüten I. Monocotyledoneae. Beitr. Biol. Pflanz. 1993, 86, 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.P.; Cai, X.H.; Wang, H.; Ren, Z.X.; Larson-Rabin, Z.; Li, D.Z. Dark purple nectar as a foraging signal in a bird-pollinated Himalayan plant. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M.; Yeo, P.; Lack, A. The Natural History of Pollination; HarperCollins: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Geerts, S.; Pauw, A. Hyper-specialization for long-billed bird pollination in a guild of South African plants: The Malachite Sunbird pollination syndrome. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2009, 75, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, H.; Quan, Q.; Wu, B.; Lv, X.; Shen, L.; Huang, S. Altitude-related shift of relative abundance from insect to sunbird pollination in Elaeagnus umbellata (Elaeagnaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 2021, 59, 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Huang, S. Nectar properties and the role of sunbirds as pollinators of the golden-flowered tea (Camellia petelotii). Am. J. Bot. 2017, 104, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, A.J.S.; Rao, S.P.; Rangaiah, K. Pollination by bats and birds in the obligate outcrosser Bombax ceiba L. (Bombacaceae), a tropical dry season flowering tree species in the Eastern Ghats forests of India. Ornithol. Sci. 2005, 4, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiepiel, I.; Johnson, S.D. Shift from bird to butterfly pollination in Clivia (Amaryllidaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2014, 101, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollerton, J.; Nuttman, C. Aggressive displacement of Xylocopa nigrita Carpenter bees from flowers of Lagenaria sphaerica (Cucurbitaceae) by territorial male Eastern Olive Sunbirds (Cyanomitra olivacea) in Tanzania. J. Pollinat. Ecol. 2013, 11, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollerton, J.; Koju, N.P.; Maharjan, S.R.; Bashyal, B. Interactions between birds and flowers of Rhododendron spp., and their implications for mountain communities in Nepal. Plants People Planet 2020, 2, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, A. Pollen transfer on birds’ tongues. Nature 1998, 394, 731–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgian, E.; Fang, Z.; Emshwiller, E.; Pidgeon, A. The pollination ecology of Rhododendron floccigerum Franchet (Ericaceae) in Weixi, Yunnan Province, China. J. Pollinat. Ecol. 2015, 16, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-H.; Song, Y.-P.; Huang, S.-Q. Evidence for passerine bird pollination in Rhododendron species. AoB Plants 2017, 9, plx062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, S.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Wang, M.; Zou, R.; Wei, X. Breeding system and bird pollination of Camellia pubipetala, a narrowly endemic plant from Karst regions of South China. Plant Species Biol. 2019, 34, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Huang, S.-Q. Generalist passerine pollination of a winter-flowering fruit tree in central China. Ann. Bot. 2012, 109, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, D.; Renner, S.S. Passerine pollination of Rhodoleia championii (Hamamelidaceae) in subtropical China. Biotropica 2010, 42, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.C.; Ferreira, B.H.; Souza, C.S.; Arakaki, L.M.; Aoki, C.; Paggi, G.M.; Sigrist, M.R. Adaptive response of extreme epiphyte Tillandsia species (Bromeliaceae) is demonstrated by different sexual reproduction strategies in the Brazilian Chaco. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 192, 840–854. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, J.C.; Goldblatt, P. Radiation of pollination systems in the Cape genus Tritoniopsis (Iridaceae: Crocoideae) and the development of bimodal pollination strategies. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2005, 166, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollerton, J.; Liede-Schumann, S.; Endress, M.E.; Meve, U.; Rech, A.R.; Shuttleworth, A.; Keller, H.A.; Fishbein, M.; Alvarado-Cárdenas, L.O.; Amorim, F.W.; et al. The diversity and evolution of pollination systems in large plant clades: Apocynaceae as a case study. Ann. Bot. 2019, 123, 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, S.; Schmid, V.S.; Zillikens, A.; Harter-Marques, B.; Steiner, J. Bimodal pollination system of the bromeliad Aechmea nudicaulis involving hummingbirds and bees. Plant Biol. 2011, 13, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.M.; Chakrabarti, P.; Chatterjee, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Dey, U.K.; Dicks, L.V.; Giri, B.; Laha, S.; Majhi, R.K.; Basu, P. Collating and validating indigenous and local knowledge to apply multiple knowledge systems to an environmental challenge: A case study of pollinators in India. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 211, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamo, P.J.; Agostini, K.; Machado, I.C.; van der Niet, T.; Maruyama, P.K. Natural history as the foundation for researching plant–pollinator interactions: Celebrating the career of Marlies Sazima. Flora 2024, 315, 152509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yan, C.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, R.; He, L.; Zheng, W. Ornamental plants associated with Buddhist figures in China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.-L.; Rho, J.-H. Cultural symbolism and acculturation of temple plants in China: Focused on ‘Bodhi Tree’. J. People Plants Environ. 2020, 23, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Song, W.; Huang, Z.; Wu, J. The values of biological diversity: A perspective from China. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 287, 110341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.L.; Phanlukthao, P. Golden Sunbird: Semiotics and cultural identity in the context of modern China. Int. J. Interdiscip. Cult. Stud. 2024, 19, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family and Bird Species | English Name | Chinese Name | Evidence * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscicapidae | |||

| Copsychus saularis (Linnaeus, 1758) | Oriental Magpie-robin | 鹊鸲 | Citizen science |

| Nectariniidae | |||

| Aethopyga gouldiae (Vigors, 1831) | Mrs Gould’s Sunbird | 蓝喉太阳鸟 | Citizen science /Our study |

| Aethopyga latouchii Slater, 1891 | Fork-tailed Sunbird | 叉尾太阳鸟 | Citizen science |

| Aethopyga siparaja (Raffles, 1822) | Crimson Sunbird | 黄腰太阳鸟 | Citizen science |

| Aethopyga vigorsii (Sykes, 1832) | Western Crimson Sunbird | 猩红太阳鸟 | Citizen science |

| Arachnothera longirostra (Latham, 1790) | Little Spiderhunter | 长嘴捕蛛鸟 | Citizen science |

| Pycnonotidae | |||

| Ixos mcclellandii (Horsfield, 1840) | Mountain Bulbul | 绿翅短脚鹎 | Citizen science |

| Pycnonotus aurigaster (Vieillot, 1818) | Sooty-headed Bulbul | 白喉红臀鹎 | Our study |

| Pycnonotus xanthorrhous (Anderson, 1869) | Brown-breasted Bulbul | 黄臀鹎 | Our study |

| Timaliidae | |||

| Pomatorhinus ruficollis Hodgson, 1836 | Streak-breasted Scimitar Babbler | 棕颈钩嘴鹛 | Our study |

| Zosteropidae | |||

| Zosterops japonicus Temminck & Schlegel, 1845 | Japanese White-Eye | 暗绿绣眼鸟 | Citizen science |

| Zosterops palpebrosus (Temminck, 1824) | Indian White-Eye | 灰腹绣眼鸟 | Our study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albuquerque-Lima, S.; Ferreira, B.H.d.S.; Rech, A.R.; Ollerton, J.; Lunau, K.; Smagghe, G.; Li, K.-Q.; Oliveira, P.E.; Ren, Z.-X. Beyond Bees: Evidence of Bird Visitation and Putative Pollination in the Golden Lotus (Musella lasiocarpa)—One of the Six Buddhist Flowers—Through Field Surveys and Citizen Science. Plants 2025, 14, 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14203157

Albuquerque-Lima S, Ferreira BHdS, Rech AR, Ollerton J, Lunau K, Smagghe G, Li K-Q, Oliveira PE, Ren Z-X. Beyond Bees: Evidence of Bird Visitation and Putative Pollination in the Golden Lotus (Musella lasiocarpa)—One of the Six Buddhist Flowers—Through Field Surveys and Citizen Science. Plants. 2025; 14(20):3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14203157

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbuquerque-Lima, Sinzinando, Bruno Henrique dos Santos Ferreira, André Rodrigo Rech, Jeff Ollerton, Klaus Lunau, Guy Smagghe, Kai-Qin Li, Paulo Eugênio Oliveira, and Zong-Xin Ren. 2025. "Beyond Bees: Evidence of Bird Visitation and Putative Pollination in the Golden Lotus (Musella lasiocarpa)—One of the Six Buddhist Flowers—Through Field Surveys and Citizen Science" Plants 14, no. 20: 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14203157

APA StyleAlbuquerque-Lima, S., Ferreira, B. H. d. S., Rech, A. R., Ollerton, J., Lunau, K., Smagghe, G., Li, K.-Q., Oliveira, P. E., & Ren, Z.-X. (2025). Beyond Bees: Evidence of Bird Visitation and Putative Pollination in the Golden Lotus (Musella lasiocarpa)—One of the Six Buddhist Flowers—Through Field Surveys and Citizen Science. Plants, 14(20), 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14203157