The Concept of Fertility in the Field of Fruit Growing and Its Evolution from Ancient Times to Present Day

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Origins of the Concept of Fertility: Mother Earth

"At the time of Kronos men lived as gods […] and the fertile land spontaneously bore many and copious fruits."

“Cursed is the ground because of you;

through painful toil you will eat food from it

all the days of your life.”(Genesis 3:17, available online at https://www.bible.com/bible/compare/GEN.3.17-19, accessed on 4 July 2025)

“Now Abel kept flocks, and Cain worked the soil. In the course of time, Cain brought some of the fruits of the soil as an offering to the Lord. And Abel also brought an offering—fat portions from some of the firstborn of his flock. The Lord looked with favor on Abel and his offering, but on Cain and his offering he did not look with favor.”(Genesis 4:2–5, available online at https://www.bible.com/bible/111/GEN.4.2-16.NIV, accessed on 4 July 2025)

3. The Symbolic Value of Fertility in the Sacred Scriptures and Arts

“In a fertile field, along the course of great waters, it was planted, to put forth branches and bear fruit and become a magnificent vine.”(Ezekiel 17:8, available online at https://www.bible.com/bible/compare/EZK.17.8-13, accessed on 4 July 2025)

“We poured the water in streams, then split the earth in furrows and made grains sprout, and vines and reeds, and olive trees and palms, and thick gardens and fruit and fodder—for your benefit and your herds.”(Surah 80, available online at https://quran.com, accessed on 4 July 2025)

“They demolished the cities; on all the fertile fields each one threw a stone and filled them; they blocked all the springs and cut down all the useful trees.”(available online at https://biblehub.com/2_kings/3-25.htm, accessed on 4 July 2025)

“Though other things grow fair against the sun,

Yet fruits that blossom first will first be ripe.”(available online at https://www.online-literature.com/shakespeare/othello/7/, accessed on 4 July 2025)

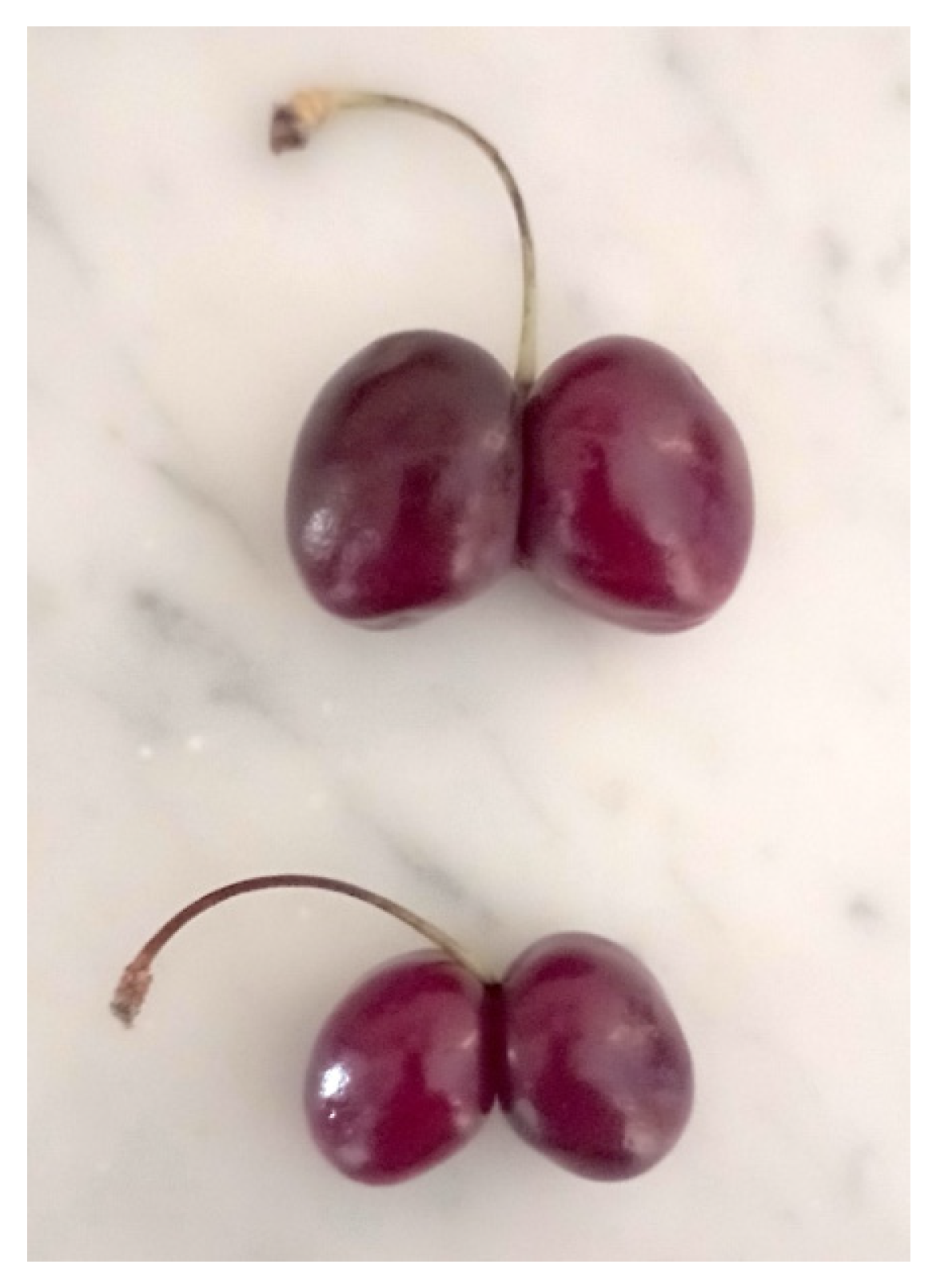

“So we grew together,

Like to a double cherry, seeming parted,

But yet a union in partition;

Two lovely berries moulded on one stem.”(available online at https://myshakespeare.com/midsummer-nights-dream/act-3-scene-2-popup-note-index-item-double-cherry, accessed on 4 July 2025)

“Has fecundado mi expiritu; recoge, pues, los

frutos primerizos.

Los frutos de la palmera son de quien la ha polinizado”.[You have fertilized my spirit; gather, then, the first fruits. The fruits of the palm tree belong to the one who pollinated it.]Ibn Zaydun (1003–1070 CE, in [7].

4. The Expansion and Evolution of the Concept of Fertility: From Soil Alone to Soil and Plant

“Recent discoveries suggest that the adoption of agriculture, supposedly our most decisive step toward a better life, was in many ways a catastrophe from which we have never recovered. With agriculture came the gross social and sexual inequality, the disease and despotism, that curse our existence.”

“You ask me to plow the ground! Shall I take a knife and tear my mother’s bosom? Then when I die she will not take me to her bosom to rest. You ask me to dig for stone! Shall I dig under her skin for her. Then when I die I cannot enter her body to be born again. You ask me to cut grass and make hay and sell it and be rich white men! But how dare I cut off my mother’s hair?”Smohalla, Chief of the Shahaptin—Indian Tribe, Washington, c. 1880. In [9].

“The pear, though cultivated in classical times, appears, from Pliny’s description, to have been a fruit of very inferior quality.

I have seen great surprise expressed in horticultural works at the wonderful skill of gardeners, in having produced such splendid results from such poor materials; but the art, I cannot doubt, has been simple, and, as far as the final result is concerned, has been followed almost unconsciously.

It has consisted in always cultivating the best known variety, sowing its seeds, and, when a slightly better variety has chanced to appear, selecting it, and so onwards”(available online at https://www.vliz.be/docs/Zeecijfers/Origin_of_Species.pdf, accessed on 4 July 2025)

“Quid est agrum bene colere? Arare; Quid secundum? Arare; Tertio? Stercorare.”[What does it mean to cultivate the land well? Well plow; What is the second? Plow; Third? To manure] (De Agri Cultura, 61, 1) (available online at https://www.thelatinlibrary.com/cato/cato.agri.html, accessed on 4 July 2025)

5. The Different Meanings of Fruit Tree Fertility

5.1. The Link Between the Biological and Agronomic Sense of Fertility

5.2. The Concept of Fertility as Regularity of Fruitfulness

5.3. The Concept of Fertility as the Development of the Fruiting Process: Potential Fertility vs. Actual Fertility

6. Towards a Unified Concept of Fertility

6.1. Reconciling Biology and Agronomy

6.2. A Digression to Broaden Our Vision

7. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Renfrew, C. Inception of agriculture and rearing in the Middle East. Comptes Rendus Palevol 2006, 5, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli-Sforza, L.L.; Menozzi, P.; Piazza, A. Demic Expansions and Human Evolution. Science 1993, 259, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhasi, R.; Fort, J.; Ammerman, A.J. Tracing the origin and spread of agriculture in Europe. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montanari, M. La Fame e L’abbondanza. Storia Dell’alimentazione in Europa; Laterza: Bari, Italy, 2005; p. 270. ISBN 9788842051626. [Google Scholar]

- Janick, J. Fruits of the bibles. HortScience 2007, 42, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janick, J. Caravaggio’s Fruit: A Mirror on Baroque Horticulture. Chron. Hortic. 2004, 44, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vernet, J. La Ciencia en Al-Andalus, Spanish Edition; Andaluzas Unidas: Sevilla, Spain, 1986; p. 56. ISBN 9788475870816. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, J. The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race; Discover Magazine: Waukesha, WI, USA, 1987; pp. 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Trafzer, C.E.; Beach, M.A. Smohalla, the Washani, and Religion as a Factor in Northwestern Indian History. Am. Indian Q. 1985, 9, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, E. Fruits and fruit trees in Aldrovandi’s “Iconographia Plantarum”. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 1990, 1990, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosoli, M. Scienziati, Contadini e Proprietari. Botanica e Agricoltura nell’Europa Occidentale, 1350–1850; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1992; p. 468. ISBN 88-06-12882-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, D. Unconscious selection and the evolution of domesticated plants. Econ. Bot. 2004, 58, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gepts, P. Crop Domestication as a Long-term Selection Experiment. In Plant Breeding Reviews; Janick, J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 24, pp. 1–44. ISBN 0470650281. [Google Scholar]

- Janick, J. The Origins of Fruits, Fruit Growing, and Fruit Breeding. Plant Breed. Rev. 2005, 25, 255–321. [Google Scholar]

- Abbo, S.; Gopher, A.; Lev-Yadun, S. Fruit Domestication in the Near East; Janick, J., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 39. [Google Scholar]

- Abbo, S.; Gopher, A. Plant domestication in the Neolithic Near East: The humans-plants liaison. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 242, 106412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Fargione, J.; Wolff, B.; Antonio, C.D.; Dobson, A.; Howarth, R.; Schindler, D.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Simberloff, D.; Swackhamer, D. Forecasting Agriculturally Driven Environmental Change. Science 2001, 292, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I. The adaptation and mitigation potential of traditional agriculture in a changing climate. Clim. Change 2017, 140, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisciotta, A.; Barone, E.; Di Lorenzo, R. Table-Grape Cultivation in Soil-Less Systems: A Review. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlaug, N. Feeding a Hungry world. Science 2007, 318, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, P.F.; Volk, G.M.; Gardner, C.; Gore, M.A.; Simon, P.W.; Smith, S. Sustaining the future of plant breeding: The critical role of the USDA-ARS national plant germplasm system. Crop Sci. 2018, 58, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suslow, T.V.; Thomas, B.R.; Bradford, K.J. Biotechnology Provides New Tools for Plant Breeding; ANR-UC Public. n° 8043: Davis, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, J. Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication. Nature 2002, 418, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.S.; Duval, A.E.; Jensen, H.R. Patterns and processes in crop domestication: An historical review and quantitative analysis of 203 global food crops. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iriondo, J.M.; Milla, R.; Volis, S.; Rubio de Casas, R. Reproductive traits and evolutionary divergence between Mediterranean crops and their wild relatives. Plant Biol. 2018, 20, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledbetter, C.A.; Ramming, D.W. Seedlessness in Grapes. Hortic. Rev. 1989, 11, 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Picarella, M.E.; Mazzucato, A. The occurrence of seedlessness in higher plants; insights on roles and mechanisms of parthenocarpy. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, M.; Smith, M.W.; Froelicher, Y.; Russo, G.; Gmitter, F.G. Traditional breeding. In The Genus Citrus; Talon, M., Caruso, M., Gmitter, F.G., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2020; pp. 129–148. ISBN 9780128121634. [Google Scholar]

- Albertini, E.; Barcaccia, G.; Mazzucato, A.; Sharbel, T.F.; Falcinelli, M. Apomixis in the Era of Biotechnology. In Plant Developmental Biology–Biotechnological Perspectives; Pua, E.C., Davey, M.R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 405–436. ISBN 978-3-642-02300-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.A.; Terol, J.; Ibanez, V.; López-García, A.; Pérez-Román, E.; Borredá, C.; Domingo, C.; Tadeo, F.R.; Carbonell-Caballero, J.; Alonso, R.; et al. Genomics of the origin and evolution of Citrus. Nature 2018, 554, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedgley, M. Flowering of Deciduous Perennial Fruit Crops. In Horticultural Reviews; Janick, J., Ed.; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1990; pp. 223–264. [Google Scholar]

- Milošević, T.; Milošević, N. Plum (Prunus spp.) Breeding. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Fruits; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 3, pp. 165–215. ISBN 9783319919447. [Google Scholar]

- Peer, L.A.; Mir, B.A. Molecular mechanisms and genetic regulation of self-incompatibility in flowering plants: Implications for crop improvement and evolutionary biology. Plant Mol. Biol. 2025, 115, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sottile, F.; Caltagirone, C.; Giacalone, G.; Peano, C.; Barone, E. Unlocking Plum Genetic Potential: Where Are We At? Horticulturae 2022, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryugo, K. Pomes. In Fruitculture. Its Science and Art; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 247–257. ISBN 0-471-89191-6. [Google Scholar]

- Soost, R.K.; Cameron, J.W. “Oroblanco”, a Triploid Pummelo-grapefruit Hybrid. HortScience 1980, 15, 667–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reforgiato Recupero, G.; Russo, G.; Recupero, S. New promising Citrus triploid hybrids selected from crosses between monoembryonic diploid female and tetraploid male parents. HortScience 2005, 40, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, A.; Gucci, R. Vegetative and reproductive biology. In The Olive: Botany and Production; Fabbri, A., Baldoni, L., Caruso, T., Famiani, F., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2024; pp. 66–93. ISBN 9781789247336. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersma, P.A. Reproductive barriers in tree fruit crops and nuts. Acta Hortic. 2003, 622, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, A.R.; Huang, H. Genetic Resources of Kiwifruit: Domestication and Breeding. In Horticultural Reviews; Janick, J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 33, pp. 1–121. ISBN 9780470168011. [Google Scholar]

- Biasi, R.; Falasca, G.; Speranza, A.; De Stradis, A.; Scoccianti, V.; Franceschetti, M.; Bagni, N.; Altamura, M.M. Biochemical and ultrastructural features related to male sterility in the dioecious species Actinidia deliciosa. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2001, 39, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retana, J.; Ramoneda, J.; Garcia Del Pino, F.; Bosch, J. Flowering phenology of carob, Ceratonia siliqua L. (Cesalpinaceae). J. Hortic. Sci. 1994, 69, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, M. Fruiting. In Physiology of Temperate Zone Fruit Trees; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 169–234. ISBN 0-471-81781-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D. Flowers and Fruit. In Temperate and Subtropical Fruit Production; Jackson, D.I., Looney, N.E., Morley-Bunker, M., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2010; pp. 33–43. ISBN 978-1-78064-074-7. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, D.J.; Mowrey, B.D.; Chaparro, J.X. Variability in Flower Bud Number Among Peach and Nectarine Cultivars. HortScience 1988, 23, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, J. Flower-bud formation. In Fundamentals of Temperate Zone Tree Fruit Production; Tromp, J., Webster, A.D., Wertheim, S.J., Eds.; Backhuys Pub.: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 204–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bangerth, K.F. Floral induction in mature, perennial angiosperm fruit trees: Similarities and discrepancies with annual/biennial plants and the involvement of plant hormones. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 122, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.M.; Samach, A. Constraints to obtaining consistent annual yields in perennial tree crops. I: Heavy fruit load dominates over vegetative growth. Plant Sci. 2013, 207, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samach, A.; Smith, H.M. Constraints to obtaining consistent annual yields in perennials. II: Environment and fruit load affect induction of flowering. Plant Sci. 2013, 207, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monselise, S.P.; Goldschmidt, E.E. Alternate bearing in fruit trees. In Horticultural Reviews; Janick, J., Ed.; AVI Publishing Co.: Roslyn, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 4, pp. 128–173. ISBN 0163-7851. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, E.E. The Evolution of Fruit Tree Productivity: A Review. Econ. Bot. 2013, 67, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavee, S. Biennial bearing in olive. Ann. Ser. Hist. Nat. 2007, 17, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, E.E.; Sadka, A. Yield Alternation: Horticulture, Physiology, Molecular Biology, and Evolution. In Horticultural Reviews; Warrington, I., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 48, pp. 363–418. ISBN 9781119750802. [Google Scholar]

- Monselise, S.P. Closing remarks. In Handbook of Fruit Set and Development; Monselise, S.P., Ed.; CRC Press, Inc.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1986; pp. 521–537. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, M.T.; Shackel, K.A. Alternate bearing in pistachio as a masting phenomenon: Construction cost of reproduction versus vegetative growth and storage. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1998, 123, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C.M.; Jordano, P.; Guitián, J.; Traveset, A. Annual variability in seed production by woody plants and the masting concept: Reassessment of principles and relationship to pollination and seed dispersal. Am. Nat. 1998, 152, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryugo, K. Promotion and inhibition of flower initiation and fruit set by plant manipulation and hormones, a review. Acta Hortic. 1986, 179, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, J.J. Integration of Physiological Information To Evaluate Fruit Tree Productivity. Acta Hortic. 1986, 175, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, D.G. Sexual Strategies in Plants: I. An Hypothesis of Serial Adjustment of Maternal Investment During One Reproductive Session. New Phytol. 1980, 86, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.C.; Greven, M.; Winefield, C.S.; Trought, M.C.T.; Raw, V. The flowering process of Vitis vinifera: A review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2009, 60, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, S. Patterns of Fruit-Set: What Controls Fruit-Flower Ratios in Plants? Evolution 1986, 40, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J.; Polito, V.S. The role of staminate flowers in the breeding system of Olea europaea (Oleaceae): An andromonoecious, wind-pollinated taxon. Ann. Bot. 2004, 93, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkie, J.D.; Sedgley, M.; Olesen, T. Regulation of floral initiation in horticultural trees. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 3215–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, A.G. Flower and Fruit Abortion: Proximate Causes and Ultimate Functions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1981, 12, 253–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, F.G.; Neilsen, J.C. Physiological Factors Affecting Biennial Bearing in Tree Fruit: The role of Seeds in Apple. Horttechnology 1999, 9, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, R.E.; Costa, G.; Vizzotto, G. Prunus, Flower and fruit thinning of peach and other Prunus. In Horticultural Reviews; Janick, J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 28, pp. 351–392. ISBN 9780471215424. [Google Scholar]

- Seifi, E.; Guerin, J.; Kaiser, B.; Sedgley, M. Inflorescence architecture of olive. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 116, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo, L.; Fernández-Escobar, R. Influence of Cultivar and Flower Thinning within the Inflorescence on Competition among Olive Fruit. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1985, 110, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.J.J.; Fereres, E. The Physiology of Adaptation and Yield Expression in Olive. In Horticultural Reviews; Janick, J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 31, pp. 155–229. ISBN 9780470650882. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Escobar, R. Tecniche colturali per il controllo della fruttificazione dell’olivo. Olivae 1993, 46, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, J.; Rallo, L.; Rapoport, H.F. Crop load effects on floral quality in olive. Sci. Hortic. 1994, 59, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, L.; Sgromo, C.; Bonofiglio, T.; Orlandi, F.; Fornaciari, M.; Ferranti, F.; Romano, B. Reproductive biology of Olive (Olea europaea L.) DOP Umbria cultivars. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2006, 19, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, H. Significance of flower and fruit thinning on fruit quality. Plant Growth Regul. 2000, 31, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, E.; Gullo, G.; Zappia, R.; Inglese, P. Effect of crop load on fruit ripening and olive oil (Olea europea L.) quality. J. Hortic. Sci. 1994, 69, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucci, R.; Lodolini, E.; Rapoport, H.F. Olive fruit growth and productivity under different irrigation regimes and crop loads. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1057, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentacoste, E.R.; Puertas, C.M.; Sadras, V.O. Effect of fruit load on oil yield components and dynamics of fruit growth and oil accumulation in olive (Olea europaea L.). Eur. J. Agron. 2010, 32, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dag, A.; Bustan, A.; Avni, A.; Tzipori, I.; Lavee, S.; Riov, J. Timing of fruit removal affects concurrent vegetative growth and subsequent return bloom and yield in olive (Olea europaea L.). Sci. Hortic. 2010, 123, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo, L.; Suárez, M.P. Seasonal distribution of dry matter within the olive fruit-bearing limb. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 1989, 3, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati, A.; Paoletti, A.; Al Hariri, R.; Morelli, A.; Famiani, F. Resource investments in reproductive growth proportionately limit investments in whole-tree vegetative growth in young olive trees with varying crop loads. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, A.; Paoletti, A.; Lodolini, E.M.; Famiani, F. Cultivar ideotype for intensive olive orchards: Plant vigor, biomass partitioning, tree architecture and fruiting characteristics. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1345182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, A.; Lodolini, E.M.; Famiani, F. From flower to fruit: Fruit growth and development in olive (Olea europaea L.)—A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1276178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.C.; Cordeiro, A.M.; Rapoport, H.F. Flower Quality in Orchards of Olive, Olea europaea L., cv. Morisca. Adv. Hort. Sci. 2006, 20, 262–266. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati, A.; Zipanćič, M.; Caporali, S.; Padula, G. Fruit weight is related to ovary weight in olive (Olea europaea L.). Sci. Hortic. 2009, 122, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, C.; Castro, A.J.; Rapoport, H.F.; Rodríguez-García, M.I. Morphological, histological and ultrastructural changes in the olive pistil during flowering. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2012, 25, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapoport, H.F.; Moreno-Alías, I.; de la Rosa-Peinazo, M.Á.; Frija, A.; de la Rosa, R.; León, L. Floral Quality Characterization in Olive Progenies from Reciprocal Crosses. Plants 2022, 11, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rallo, L.; Cuevas, J. Fructificaciòn y producciòn. In El Cultivo del Olivo, 4th ed.; Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2004; pp. 121–152. ISBN 9788484761907. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G.C. Olive flower and fruit population dynamics. Acta Hortic. 1990, 286, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiani, F.; Farinelli, D.; Gardi, T.; Rosati, A. The cost of flowering in olive (Olea europaea L.). Sci. Hortic. 2019, 252, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J. Why Olive Produces Many More Flowers than Fruit—A Critical Analysis. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, H.F. The reproductive biology of the olive tree and its relationship to extreme environmental conditions. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1057, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, D.G.; Webb, C.J. Secondary Sex Characters in Plants. Bot. Rev. 1977, 43, 177–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.P.; Fernández-Escobar, R.; Rallo, L. 1984. Competition among fruits in olive II. Influence of inflorescence or fruit thinning and cross-pollination on fruit set components and crop efficiency. Acta Hort. 1984, 149, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, A.; Zipanćič, M.; Caporali, S.; Paoletti, A. Fruit set is inversely related to flower and fruit weight in olive (Olea europaea L.). Sci. Hortic. 2010, 126, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutte, G.W.; Martin, G.C. Effect of killing the seed on return bloom of olive. Sci. Hortic. 1986, 29, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, C.M.; Trujillo, I.; Martinez-Urdiroz, N.; Barranco, D.; Rallo, L.; Marfil, P.; Gaut, B.S. Olive domestication and diversification in the Mediterranean Basin. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugini, E.; Cristofori, V.; Silvestri, C. Genetic improvement of olive (Olea europaea L.) by conventional and in vitro biotechnology methods. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rallo, L.; Díez, C.M.; Morales-Sillero, A.; Miho, H.; Priego-Capote, F.; Rallo, P. Quality of olives: A focus on agricultural preharvest factors. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 233, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braudel, F. Civiltà e Imperi del Mediterraneo Nell’età di Filippo II; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2010; ISBN 9788806204006. [Google Scholar]

- Haberman, A.; Bakhshian, O.; Cerezo-Medina, S.; Paltiel, J.; Adler, C.; Ben-Ari, G.; Mercado, J.A.; Pliego-Alfaro, F.; Lavee, S.; Samach, A. A possible role for flowering locus T-encoding genes in interpreting environmental and internal cues affecting olive (Olea europaea L.) flower induction. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, A.I.; Rallo, P.; Suárez, M.P.; Torres-Sánchez, J.; Casanova, L.; Jiménez-Brenes, F.M.; Morales-Sillero, A.; Jiménez, M.R.; López-Granados, F. High-Throughput System for the Early Quantification of Major Architectural Traits in Olive Breeding Trials Using UAV Images and OBIA Techniques. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo, L.; Barranco, D.; Díez, C.M.; Rallo, P.; Suárez, M.P.; Trapero, C.; Pliego-Alfaro, F. Strategies for Olive (Olea europaea L.) Breeding: Cultivated Genetic Resources and Crossbreeding. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Fruits; Al-Khayri, J., Jain, S., Johnson, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 3, pp. 535–600. ISBN 9783319919447. [Google Scholar]

- Grisafi, F.; Dejong, T.M.; Tombesi, S. Fruit tree crop models: An update. Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Breeding System | Self-Compatibility x | Type of Pollination y | Fertility z | Average Fruit-Set (%) | Flowering Period | Other Relevant Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almond | Allogamous | Mostly SI (some SC cvs.) | En | Hi | 10–30% | Very early (Feb–Mar) | Very frost-sensitive |

| Apple | Allogamous | SI | En | Hi | 5–15% | Mid-season (Apr–May) | Gametophytic SI requires (not triploid) pollinizers |

| Apricot | Largely autogamous | Mostly SC (some SI cvs.) | En | Me-Hi | 20–40% | Early (Feb–Mar) | High frost sensitivity; short bloom period |

| Carob | Polygamous-Dioecious | N/A | En + some An | Lo–Me | <10% | Late (Sep–Nov) | Protogynous; very labile sexual expression |

| Grape | Mostly autogamous, cleistogamous | SC | some An | Hi | 20–40% | Spring (May–Jun) | Perfect flowers; parthenocarpy in seedless grapes |

| Hazelnut | Monoecious, dichogamous | Mostly SI | An | Me | 10–20% | Very early (Jan–Feb) | Protogyny |

| Kiwi | Dioecious | N/A | En | Me–Hi | 15–30% | Spring (Apr–May) | Male/female plants needed; pollen viability critical |

| Lemon | Autogamous | SC | En | Me–Hi | 10–20% | Extended (reflowering) | Very high flower density; parthenocarpy and polyembryony frequent |

| Mandarin | Variable | Many SI, some SC cvs. | En | Va | 5–15% | Spring (Mar–Apr) | Seedless forms via parthenocarpy; nucellar embryony |

| Olive | Andromonoecius | Largely SI (partially SC) | An | Lo–Me | 1–3% | Late spring (May–Jun) | High flower abortion; alternate bearing |

| Peach | Autogamous | Mostly SC | En | Me–Hi | 20–40% | Early (Mar) | Early bloom |

| Pear | Allogamous | SI | En | Mo | 5–10% | Early–mid (Mar–Apr) | Some parthenocarpy; SI requires compatible cvs. |

| Pistachio | Dioecious | N/A | An | Lo | 1–2% | Spring (Apr–May) | Male–female synchrony crucial; alternate bearing |

| Plum (European) | Largely Autogamous | SC and SI cvs. | En | Me | 10–20% | Early–mid (Mar–Apr) | Cross-pollination is advantageous |

| Sweet Cherry | Allogamous | Largely SI | En | Hi | 5–10% | Early (Mar–Apr) | Rain-sensitive bloom; compatible pollinizers needed |

| Sweet Orange | Autogamous | SC | En | Me–Hi | 10–20% | Spring (Mar–Apr) | Some nucellar embryony; parthenocarpy possible |

| Walnut | Monoecious, dichogamous (protandry/protogyny) | SC (dichogamy reduces autogamy) | An | Me | 5–10% | Spring (Apr–May) | Cross-pollination improves yield; female flowers on terminals or laterals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barone, E. The Concept of Fertility in the Field of Fruit Growing and Its Evolution from Ancient Times to Present Day. Plants 2025, 14, 2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14182883

Barone E. The Concept of Fertility in the Field of Fruit Growing and Its Evolution from Ancient Times to Present Day. Plants. 2025; 14(18):2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14182883

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarone, Ettore. 2025. "The Concept of Fertility in the Field of Fruit Growing and Its Evolution from Ancient Times to Present Day" Plants 14, no. 18: 2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14182883

APA StyleBarone, E. (2025). The Concept of Fertility in the Field of Fruit Growing and Its Evolution from Ancient Times to Present Day. Plants, 14(18), 2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14182883