Abstract

Several Acacia species are aggressive invaders outside their native range, often occupying extensive areas. Traditional management approaches have proven to be ineffective and economically unfeasible, especially when dealing with large infestations. Here, we explain a different approach to complement traditional management by using the waste from Acacia management activities. This approach can provide stakeholders with tools to potentially reduce management costs and encourage proactive management actions. It also prioritizes potential applications of Acacia waste biomass for agriculture and forestry as a way of sequestering the carbon released during control actions. We advocate the use of compost/vermicompost, green manure and charcoal produced from Acacia waste, as several studies have shown their effectiveness in improving soil fertility and supporting crop growth. The use of waste and derivatives as bioherbicides or biostimulants is pending validation under field conditions. Although invasive Acacia spp. are banned from commercialization and cultivation, the use of their waste remains permissible. In this respect, we recommend the collection of Acacia waste during the vegetative stage and its subsequent use after being dried or when dead, to prevent further propagation. Moreover, it is crucial to establish a legal framework to mitigate potential risks associated with the handling and disposal of Acacia waste.

1. Introduction

Australian Acacia species are aggressive invasive species that severely affect ecosystem structure and functioning globally [1,2]. Recognized as ecosystem transformers [3], invasive Acacia species provide some beneficial goods, but adverse impacts tend to outweigh the benefits as their invasion increases [2]. The negative impacts encompass both below- and above-ground components of the ecosystem they invade [4,5].

Some invasive Acacia species are widely distributed, covering large areas and forming dense and homogeneous stands [6,7]. In Europe, the invasion of Acacia species is particularly severe in the Iberian Peninsula [6,7] and Italy [8,9]. To prevent the spread of Acacia propagules in the Iberian Peninsula, for example, the cultivation and commercialization of the most aggressive specimens is prohibited by legislation (in Portugal by the Decree-Law no. 92/10 July 2019; and in Spain by the Royal Decree 630/2 August 2013). In addition, increasing efforts have been made in recent decades to control and prevent introduction of Acacia species and increase public and stakeholder engagement [10]. Despite this, the management of invasive Acacia species is far from successful, mainly due to the lack of resources to implement long-term control actions in large invaded areas [7,8,9,10,11]. At this point, eradication of aggressive Acacia species is considered economically and realistic unfeasible and their management remains challenging [7,11], emphasizing the need to prioritize control in small areas of high ecological value [10].

Some traits of invasive Acacia species, including nitrogen-fixation, large quantities of long-lived seeds, rapid growth and vigorous resprouting from stumps or roots following disturbance, contribute to a continuous production of biomass and make its management very difficult [2,10,12,13,14]. This situation, together with a lack of resources, frequently leads stakeholders to abandon Acacia control, thereby aggravating the problems of Acacia invasion [personal observation]. Here, we advocate the need to overcome these management barriers to avoid abandonment and make control more attractive. The valorization of Acacia waste can be a complementary way to potentially reduce costs and stimulate management actions [7,10,11]. There are several potential uses for waste derived from Acacia species, which have recently been reviewed by Lorenzo and Morais [11] and López-Hortas [15]. However, there is a knowledge gap regarding what uses should be prioritized. This work aims to extend the findings of Lorenzo and Morais [11] and López-Hortas [15] by identifying uses related to agricultural and forestry purposes, as these systems can act as a sink for high amounts of organic matter, thereby sequestering carbon. We focus on the most promising uses that have been reported for the waste of the most invasive Acacia species [16,17], highlighting characteristics that are desirable for agriculture and forestry and discussing their feasible application. We also provide some recommendations for best practices in the use of Acacia waste.

2. Bioactive Compounds as Potential Bioherbicides or Biostimulants

Chemical compounds from Acacia waste that show bioactivity can be a source of natural inhibitors or stimulants of plant growth (Table 1), thereby reducing the application of synthetic agrochemicals responsible for health and environmental concerns.

Studies of Acacia dealbata Link waste found that methyl cinnamate, identified in methanolic extracts from flowers, negatively affected early seedling growth and related germination enzymatic activities in species with small seeds such as Lolium rigidum Gaudin (weed) and lettuce (crop), whereas it did not affect wheat (crop with larger seeds) under laboratory conditions [18]. Interestingly, concentrations of methyl cinnamate that had a negative effect on L. rigidum did not affect wheat, and could help to control this weed in wheat crops [18]. Similarly, water-soluble compounds present in ethanolic extracts obtained from A. dealbata leaves consistently reduced the radicle length of L. sativa in Petri-dish bioassays with either dimethyl sulfoxide or water, suggesting a potentially strong bioherbicidal activity regardless of assay conditions [19]. Additionally, aqueous extracts from A. dealbata bark inhibited the radicle length of several urban weeds in Petri dish bioassays [20], but the negative effect almost disappeared in the presence of field soil [20]. These extracts also tended to reduce plant biomass when sprayed on weed leaves in a greenhouse experiment [20]. Conversely, bark compounds extracted with a methanolic-distilled water solution (97:3 v/v) increased total biomass and content of soluble sugars of onions grown in salinized agricultural soils [21].

On the other hand, extracts from Acacia melanoxylon R.Br. (flowers), Acacia saligna (Labill.) H.L. Wendl. (flowers), Acacia mearnsii De Wild. (leaves and roots) and Acacia retinodes (Schltdl.) (flowers) inhibited germination or growth of different weeds [22].

Both negative and positive effects of compounds/extracts of Acacia waste were mainly assessed under controlled conditions, suggesting their potential use as bioherbicides and/or growth promoters. However, these assessments represent only half of the process. We encourage the completion of the process by conducting field studies and identifying chemical composition (not strictly required) to validate the obtained results and better understand and/or forecast the effect of the extracts.

In addition, green manure of A. dealbata and Acacia longifolia (Andrews) Willd. (leaves and small branches directly incorporated into agricultural soil) was effective in reducing the density of maize-accompanying dicotyledon weeds without significantly affecting crop and soil microbes in pots [23]. At field scale, green manure and mulch of A. dealbata partially controlled dicotyledon weeds at sites with low weed density [23]. The phytotoxic effect of A. dealbata green manure on weeds was later corroborated by a decrease in weed biomass for three months after green manure incorporation in fields devoted to maize crops, which could contribute to reducing the application of synthetic herbicides in maize-based cropping systems [24]. Despite these interesting results, we consider that the bioherbicidal effect should be proved for crops other than maize.

3. Biomass Waste as a Source of Soil Amendments and Organic Fertilizers

Invasive Acacia species increase soil nitrogen (N) pools and fluxes through N fixation and they alter the concentrations of other nutrients [2], allowing them to produce abundant plant material and, in turn, copious amounts of litter enriched with N and carbon (C) [25]. The C/N ratio for A. dealbata and A. longifolia ranged from 13.6 to 30 for the foliar and branch mass fraction [26]. Green waste with a C/N ratio between 20 and 30 is suitable for composting [27]. Therefore, waste from invasive Acacia species might provide organic products with fertilizing properties.

Composting of Acacia waste, alone or mixed with other organic material, is the most common approach to processing large quantities of plant material and evaluating its use (Table 1). For example, Adam et al. [28] amended field soils with compost generated from the biowaste of Acacia podalyriifolia A. Cunn. ex G. Don (woody A. podalyriifolia + invasive herbaceous biomass, 1:1 biomass ratio) and compared its effect on plant performance with a commercial compost and soils with no amendment. Nitrogen and phosphorus (P) levels were lower in the biowaste compost than in the commercial one, but the C/N ratio was similar. Despite this, biomass production of 28-day-old maize and pea seedlings was equivalent between biowaste compost and commercial compost and higher than in soils with no amendment. Brito et al. [29] evaluated the procedure feasibility of composting A. longifolia and Acacia melanoxylon R.Br. waste from control actions. They found that the production of Acacia compost (60% A. longifolia:40% A. melanoxylon) required an extended period and specific technical procedures. However, composting proved to be an effective process for recovering organic matter and nutrients from Acacia waste as it rendered the final product suitable for organic soil amendment or replacing pine bark compost in horticultural substrates [29,30]. Composting Acacia waste biomass combined with pine bark also provides compost that can be used as a component in horticultural substrates and soil amendments [31]. Similarly, Ulm et al. [32] demonstrated that a mixture of A. longifolia waste compost and municipal compost (1:2 v/v) produced reasonable maize yields (up to 8.3 t ha−1) in plots in an urban agricultural context, highlighting the role of this soil amendment in recycling organic waste and increasing soil organic matter, thus mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. In another example, exploring the composting of sewage sludge with A. dealbata biomass in a 1:1 ratio resulted in a decline in initial content of heavy metals, and, when added to agricultural soils, this mixture did not negatively affect enzymatic activities related to soil nutrient cycling [33]. Alternatively, vermicompost and charcoal can be good soil amendments. Vermicomposting of A. dealbata leaves, flowers and young branches rendered a product without phytotoxicity that met EU quality standards for organic fertilizers [34]. Charcoal produced from Acacia decurrens (J.C.Wendl.) Willd. wood resulted in improvements in soil organic carbon and total N and nutrients in soils under the Eragrostis tef Zucc-Acacia decurrens–charcoal production rotation system, compared with the Eragrostis tef monoculture system [35].

However, some growth limitations may also occur when using composts from invasive Acacia species. These limitations could be overcome by optimizing some parameters in the composts. For example, compost made with freshly shredded branches of Acacia cyclops A. Cunn. ex G. Don. produced vigorous but smaller plants compared with a standard substrate [36,37]. In this case, the quality of seedlings might be increased by improving the initial structure and adjusting drying–wetting and fertilization regimes in the compost. In addition, Bakry et al. [36,37] indicated that such Acacia-compost-based growing substrates are of reproducible quality and suitable for the production of forest seedlings in a nursery system, especially in resource-limited countries, due to a simplified and easy-to-monitor production process. In another case, compost or vermicompost from mixtures of 20% Acacia mearnsii De Wild bark bagasse and 80% bovine manures showed toxic effects on germination and root elongation of lettuce [38]. However, increasing the proportion of bark bagasse in the mixture by up to 50% reduced the toxicity to safe levels and showed adequate physical and mineral composition for growing acid pH- and Cu-tolerant crops [38].

Acacia waste can also be used without being subjected to a composting process, which may facilitate waste management. Lorenzo et al. [24] evaluated the value of A. dealbata green manure as an organic fertilizer in maize crops under field conditions. They found that green manure incorporated into the soil four months before sowing can provide some of the nutrients needed for maize growth, with additional N fertilization being necessary to correct minor nutrient deficiencies. This suggests that inorganic fertilization can be partially replaced by A. dealbata green manure and that A. dealbata waste can be used in agriculture with minimal transformation.

Interestingly, we highlight that most of the studies described in this section were conducted with field soil or under field conditions, mimicking natural conditions and revealing the feasibility of these uses. A very promising study on the use of Acacia waste is being conducted within the R3forest project [10]. In this project, compost made from Acacia waste is being used in an ongoing reforestation context in Portugal to assess the survival of two native forest species planted in cleared invaded areas. Results from the first year showed that the survival rates of both species more than doubled in the compost treatments compared with the control, suggesting that the benefits of compost might help to counterbalance initial costs of Acacia management [10]. The authors of this project also developed a toolbox for modelling A. longifolia biomass [26]. With that, stakeholders can easily obtain information on the quantity and quality of A. longifolia biomass, which can be used for different purposes [26]. Certainly, this model could be extrapolated to other invasive Acacia species with similar growth patterns.

Table 1.

Summary of possible uses for Acacia waste related to agricultural and forestry purposes.

Table 1.

Summary of possible uses for Acacia waste related to agricultural and forestry purposes.

| Waste Characteristics | Invasive Species | Geographic Study Area | Material | Proposed Use | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity | Acacia dealbata | Spain | Methyl cinnamate from flowers | Bioherbicide | [18] |

| A. dealbata | Spain | Leaf extract | Bioherbicide | [19] | |

| A. dealbata | Portugal | Bark extract | Bioherbicide | [20] | |

| A. dealbata | Spain | Green manure from leaves and small branches | Bioherbicide | [23,24] | |

| A. dealbata | Spain | Bark extract | Stimulating activity | [21] | |

| Acacia longifolia | Spain | Green manure from leaves and small branches | Bioherbicide | [23] | |

| Acacia mearnsii | Not indicated | Leaf and root extracts | Bioherbicide | [22] | |

| Acacia melanoxylon | Not indicated | Flower extract | Bioherbicide | [22] | |

| Acacia saligna | Not indicated | Flower extract | Bioherbicide | [22] | |

| Acacia retinodes | Not indicated | Flower extract | Bioherbicide | [22] | |

| Soil improvers and fertilizers | Acacia cyclops | Canada, Marrakech | Shredded branches | Compost, growing substrates | [36,37] |

| A. dealbata | Spain | Leaves and small branches | Green manure, organic fertilizer | [24] | |

| A. dealbata | Spain | Aerial biomass mixed with sewage sludge | Compost, soil amendment | [33] | |

| A. dealbata | Spain | Leaves, flowers and young branches | Vermicompost | [34] | |

| Acacia decurrens | Ethiopia | Wood | Biochar, soil amendment | [35] | |

| A. longifolia | Portugal | Aerial biomass | Compost, soil amendment | [10] | |

| A. longifolia and Acacia melanoxylon | Portugal | Acacia aerial biomass | Compost | [29,30] | |

| A. longifolia and Acacia melanoxylon | Portugal | A. longifolia aerial biomass mixed with pine bark | Compost | [31] | |

| A. longifolia | Portugal | Leaves and small branches mixed with municipal compost | Compost | [32] | |

| Acacia mearnsii | Brazil | Bark bagasse mixed with bovine manure | Vermicompost | [38] | |

| Acacia podalyriifolia | South Africa | Aerial biomass mixed with herbaceous plants | Compost | [28] |

4. Final Remarks and Considerations

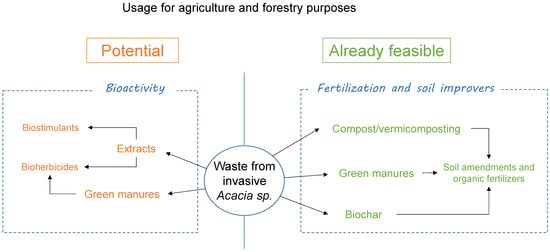

Invasive Acacia spp. continue to expand rapidly [39,40]. Current control strategies for Acacia invasions are expensive and ineffective on a large scale and in the long term [11]. Therefore, urgent and additional efforts are required to manage invasions of Acacia. The considerable amount of biomass waste generated during management actions can be considered as a low-cost resource for obtaining different end-products, and this is receiving increasing interest [7,15,41]. In our opinion, soil agricultural and forestry purposes should be prioritized as a way to sequester the carbon released during this management. We highlight the promising use of Acacia waste to produce compost/vermicompost, green manure and charcoal to improve soil fertility and reduce the application of inorganic fertilizer. Nursery and field studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using these products for growing some crops and trees and have proved to be a starting point for evaluating their application in different agricultural and forestry systems (Figure 1). In addition, compost, green manure and charcoal feed on and process large quantities of Acacia waste obtained after control actions. Conversely, the bioactivity (mainly as herbicide) of natural compounds from Acacia waste, although valuable, is not yet fully developed due to a lack of field experiments (Figure 1). These uses offer promising avenues for controlling the spread of invasive Acacia populations by constantly removing their biomass. Although the commercialization and cultivation of live invasive Acacia plants are forbidden in several European countries, the use of their waste is not yet regulated and a legal framework should be defined to prevent the spread of propagules [11]. However, due to the critical status of Acacia invasion, we propose to complement current control methods with the use of Acacia waste as a combined management strategy. This strategy must be implemented exclusively during the vegetative phenological stage (avoiding seeds) and after the waste is dried/dead to limit dispersion risks, which could facilitate a continuous control of the Acacia populations. Additionally, there is a lack of cost–benefit analysis of the use of Acacia waste to reduce control costs. We strongly recommend that, as emphasized by Ortega et al. [42], profits from using Acacia waste should be directed towards reducing costs related to control in the area occupied by these aggressive invaders, preferably within a regulatory framework.

Figure 1.

Classification of potential or feasible agricultural and forestry uses of waste biomass of invasive Acacia species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, literature search and writing of the first version, P.L.; review and editing the final version, P.L. and M.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P.—in the framework of the Project UIDP/04004/2020 and DOI identifier 10.54499/UIDP/04004/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/04004/2020). This work was also supported by national funds by FCT under the projects UIDB/04033/2020 (CITAB; https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04033/2020) and LA/P/0126/2020 (Inov4Agro; https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0126/2020). P.L. was supported by the Portuguese FCT (grant SFRH/BPD/88504/2012; contract IT057-18-7248).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumschick, S.; Cally Jansen, C. Evidence-based impact assessment for naturalized and invasive Australian Acacia species. In Wattles: Australian Acacia Species around the World; Richardson, D.M., Le Roux, J.J., Marchante, E., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2023; pp. 359–381. [Google Scholar]

- Le Maitre, D.C.; Máguas, C.; Florian, U.; Marchante, H. Ecological impacts and changes in ecosystem services and disservices mediated by invasive Australian Acacia species. In Wattles: Australian Acacia Species around the World; Richardson, D.M., Le Roux, J.J., Marchante, E., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2023; pp. 342–358. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D.M.; Pysek, P.; Rejmánek, M.; Barbour, M.G.; Panetta, D.; West, C.J. Naturalization and invasion of alien plants: Concepts and definitions. Divers. Distrib. 2000, 6, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Maitre, D.C.; Gaertner, M.; Marchante, E.; Ens, E.J.; Holmes, P.M.; Pauchard, A.; O’Farrell, P.J.; Rogers, A.M.; Blanchard, R.; Blignaut, J.; et al. Impacts of invasive Australian acacias: Implications for management and restoration. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 1015–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.M.; Le Roux, J.J.; Marchante, E. (Eds.) Wattles: Australian Acacia Species around the World; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2023; p. 544. [Google Scholar]

- Marchante, E.; Gouveia, A.C.; Brundu, G.; Marchante, H. Australian Acacia Species in Europe. In Wattles: Australian Acacia Species around the World; Richardson, D.M., Le Roux, J.J., Marchante, E., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2023; pp. 148–166. [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Alonso, P.; Rodríguez, J.; González, L.; Lorenzo, P. Here to stay. Recent advances and perspectives about Acacia invasion in Mediterranean areas. Ann. For. Sci. 2017, 74, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celesti-Grapow, L.; Bassi, L.; Brundu, G.; Camarda, I.; Carli, E.; D’auria, G.; Del Guacchio, E.; Domina, G.; Ferretti, G.; Foggi, B.; et al. Plant invasions on small Mediterranean islands: An overview. Plant Biosyst. 2016, 150, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnaro, T.; Brundu, G.; Burrascano, S.; Celesti-Grapow, L.; La Mantia, T.; Sitzia, T.; Badalamenti, E. Tree invasions in Italian forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 521, 120382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchante, E.; Colaço, M.C.; Skulska, I.; Ulm, F.; González, L.; Duarte, L.N.; Neves, S.; Gonçalves, C.; Maggiolli, S.; Dias, J.; et al. Management of invasive Australian Acacia species in the Iberian Peninsula. In Wattles: Australian Acacia Species around the World; Richardson, D.M., Le Roux, J.J., Marchante, E., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2023; pp. 438–454. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, P.; Morais, M.C. Strategies for the management of aggressive invasive plant species. Plants 2023, 12, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, P.; Gonzalez, L.; Reigosa, M.J. The genus Acacia as invader: The characteristic case of Acacia dealbata Link in Europe. Ann. For. Sci. 2010, 67, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R.; Raposo, M.A.M.; Meireles, C.I.R.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Ribeiro, N.M.C.A. Control of invasive forest species through the creation of a value chain: Acacia dealbata biomass recovery. Environments 2020, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, M.A.M.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Nunes, L.J.R. Evaluation of species invasiveness: A case study with Acacia dealbata Link. on the slopes of Cabeça (Seia-Portugal). Sustainability 2021, 13, 11233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hortas, L.; Rodríguez-González, I.; Díaz-Reinoso, B.; Torres, M.D.; Moure, A.; Domínguez, H. Tools for a multiproduct biorefinery of Acacia dealbata biomass. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 169, 113655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.M.; Rejmánek, M. Trees and shrubs as invasive alien species—A global review. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 788–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.M.; Carruthers, J.; Hui, C.; Impson, F.A.; Miller, J.T.; Robertson, M.P.; Rouget, M.; Le Roux, J.J.; Wilson, J.R. Human-mediated introductions of Australian acacias—A global experiment in biogeography. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, P.; Reboredo-Durán, J.; Múñoz, L.; Freitas, H.; González, L. Herbicidal properties of the commercial formulation of methyl cinnamate, a natural compound in the invasive silver wattle (Acacia dealbata). Weed Sci. 2020, 68, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, P.; Reboredo-Durán, J.; Múñoz, L.; González, L.; Freitas, H.; Rodríguez-Echeverría, S. Inconsistency in the detection of phytotoxic effects: A test with Acacia dealbata extracts using two different methods. Phytochem. Lett. 2016, 15, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, D.; Galhano, C.; Dias, M.C.; Castro, P.; Lorenzo, P. Invasive plants and agri-food waste extracts as sustainable alternatives for the pre-emergence urban weed control in Portugal Central Region. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2023, 30, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, P.; Souza-Alonso, P.; Guisande-Collazo, A.; Freitas, H. Influence of Acacia dealbata Link bark extracts on the growth of Allium cepa L. plants under high salinity conditions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4072–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanatas, P. Potential role of Eucalyptus spp. and Acacia spp. allelochemicals in weed management. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 80, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Alonso, P.; Puig, C.G.; Pedrol, N.; Freitas, H.; Rodríguez-Echeverría, S.; Lorenzo, P. Exploring the use of residues from the invasive Acacia sp. for weed control. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2020, 35, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, P.; Álvarez-Iglesias, L.; González, L.; Revilla, P. Assessment of Acacia dealbata as green manure and weed control for maize crop. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 37, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchante, E.; Kjøller, A.; Struwe, S.; Freitas, H. Short-and long-term impacts of Acacia longifolia invasion on the belowground processes of a Mediterranean coastal dune ecosystem. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 40, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulm, F.; Estorninho, M.; de Jesus, J.G.; de Sousa Prado, M.G.; Cruz, C.; Máguas, C. From a Lose–Lose to a win–win situation: User-friendly biomass models for Acacia longifolia to aid research, management and valorisation. Plants 2022, 11, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Torres, M.; Oviedo-Ocaña, E.R.; Dominguez, I.; Komilis, D.; Sánchez, A. A systematic review on the composting of green waste: Feedstock quality and optimization strategies. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, Y.; Sershen; Ramdhani, S. Maize and pea germination and seedling growth responses to compost generated from biowaste of selected invasive alien plant species. Compost Sci. Util. 2016, 24, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.M.; Mourão, I.; Coutinho, J.; Smith, S. Composting for management and resource recovery of invasive Acacia species. Waste Manag. Res. 2013, 31, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, L.M.; Reis, M.; Mourão, I.; Coutinho, J. Use of acacia waste compost as an alternative component for horticultural substrates. Commun. Soil Sci. 2015, 46, 1814–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.M.; Mourão, I.; Coutinho, J.; Smith, S.R. Co-composting of invasive Acacia longifolia with pine bark for horticultural use. Environ. Technol. 2015, 36, 1632–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulm, F.; Avelar, D.; Hobson, P.; Penha-Lopes, G.; Dias, T.; Máguas, C.; Cruz, C. Sustainable urban agriculture using compost and an open-pollinated maize variety. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, M.; Gómez, I.; Fernández-Boy, E.; Díaz, M.J. Effects of sewage sludge and Acacia dealbata composts on soil biochemical and chemical properties. Commun. Soil Sci. 2014, 45, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintela-Sabarís, C.; Mendes, L.A.; Domínguez, J. Vermicomposting as a sustainable option for managing biomass of the invasive tree Acacia dealbata Link. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshir, M.; Yimer, F.; Brüggemann, N.; Tadesse, M. Soil properties of a tef-Acacia decurrens-charcoal production rotation system in Northwestern Ethiopia. Soil Syst. 2022, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, M.; Lamhamedi, M.S.; Caron, J.; Bernier, P.Y.; Zine, E.A.A.; Stowe, D.C.; Margolis, H.A. Changes in the physical properties of two Acacia compost-based growing media and their effects on growth and physiological variables of containerized carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) seedlings. New For. 2013, 44, 827–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, M.; Lamhamedi, M.S.; Caron, J.; Margolis, H.; Zine El Abidine, A.; Bellaka, M.H.; Stowe, D.C. Are composts from shredded leafy branches of fast-growing forest species suitable as nursery growing media in arid regions? New For. 2012, 43, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.E.M.; de Quevedo, D.M.; Jahno, V.D. Evaluation of the vermicomposting of Acacia mearnsii De Wild bark bagasse with bovine manure. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarella, C.M.; Laface, V.L.A.; Angiolini, C.; Bacchetta, G.; Bajona, E.; Banfi, E.; Barone, G.; Biscotti, N.; Bonsanto, D.; Calvia, G.; et al. New alien plant taxa for Italy and Europe: An update. Plants 2024, 13, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Arcusa, S.; Coimbra, C.; Ferreira, V. Invasion of temperate riparian forests by Acacia dealbata affects macroinvertebrate community structure in streams. Limnetica 2024, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Loureiro, L.M.E.F.; Sá, L.C.R.; Matias, J.C.O. Energy recovery from invasive species: Creation of value chains to promote control and eradication. Recycling 2021, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Z.; Romero, F.; Paz, R.; Suárez, L.; Benítez, A.N.; Marrero, M.D. Valorization of invasive plants from Macaronesia as filler materials in the production of natural fiber composites by rotational molding. Polymers 2021, 13, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).