Ethnobotanical Documentation of the Uses of Wild and Cultivated Plants in the Ansanto Valley (Avellino Province, Southern Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

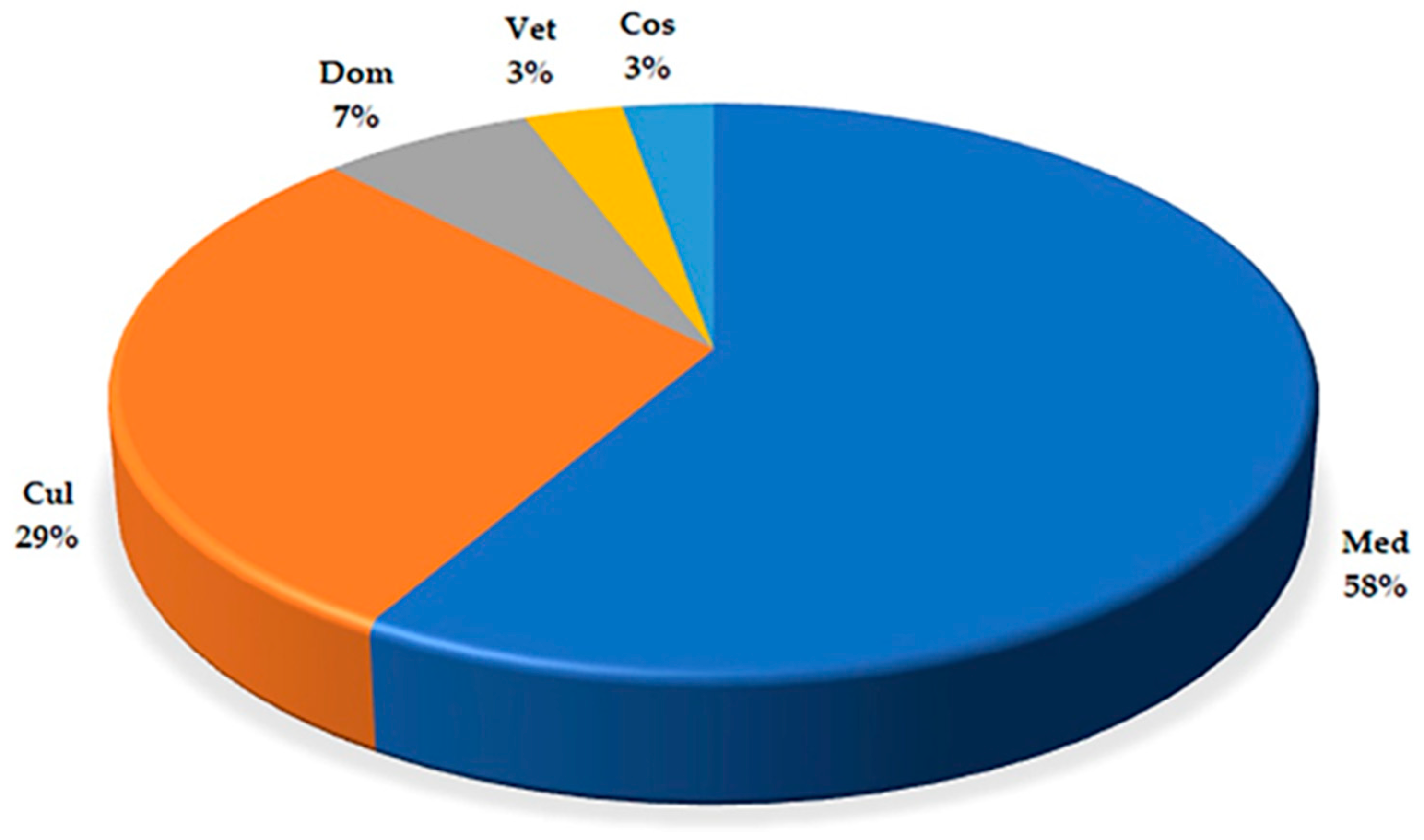

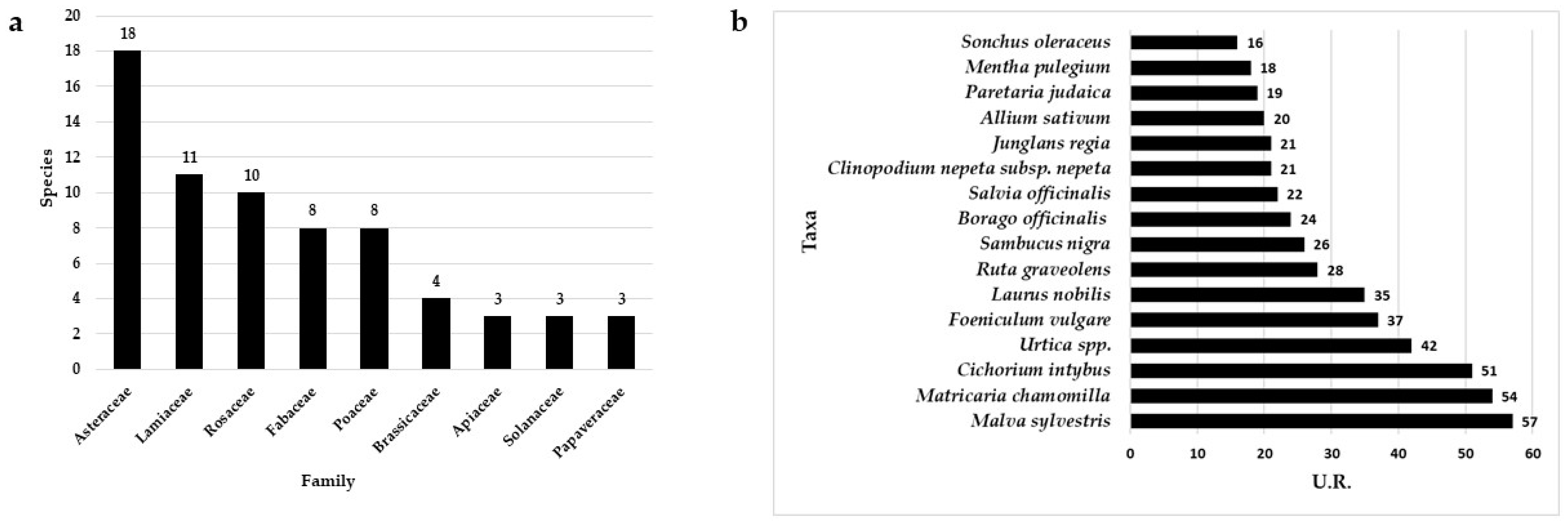

2. Results and Discussion

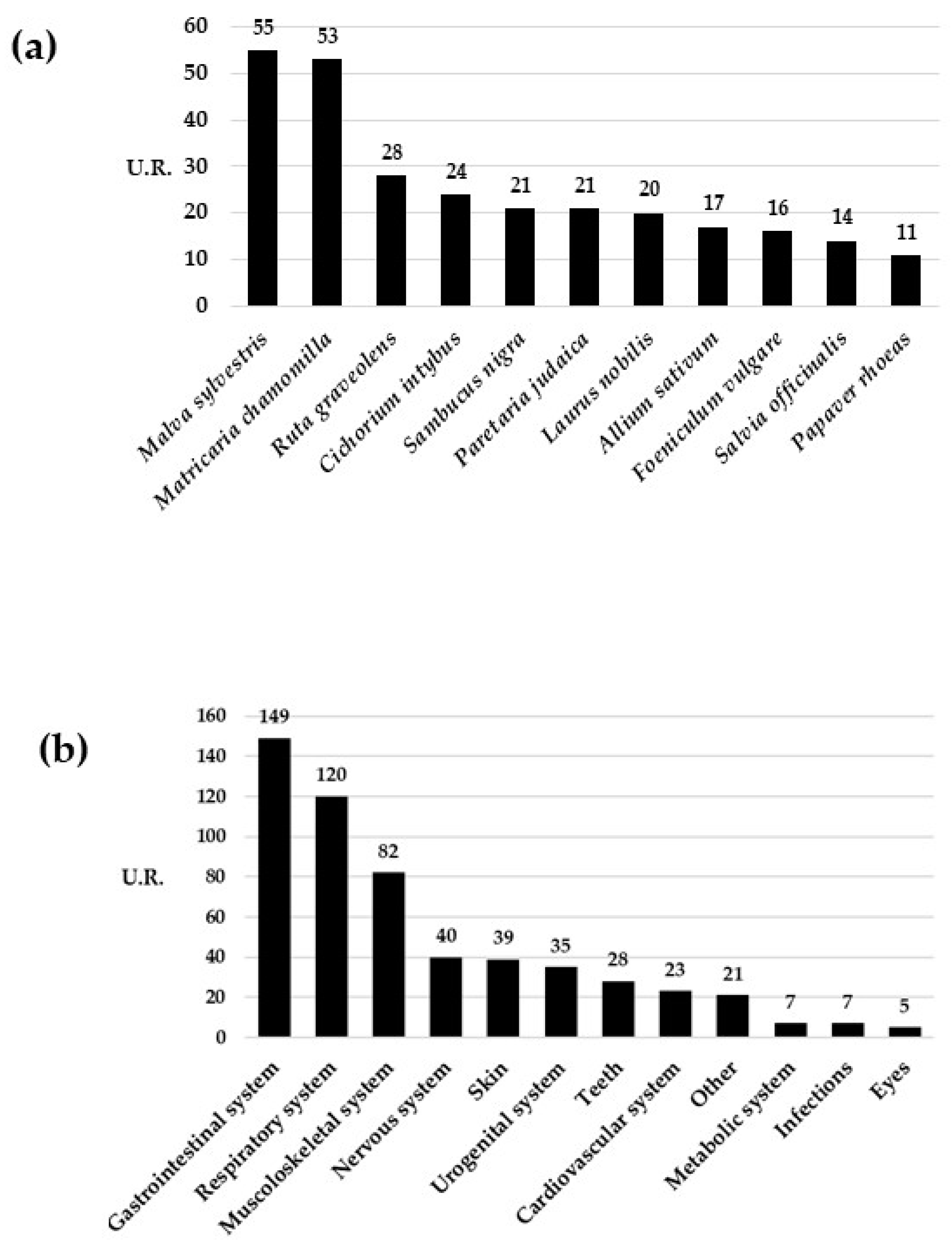

2.1. Medicinal Plants

2.2. Food Plants

2.3. Cosmetic Plants

2.4. Plants for Domestic and Craft Uses

2.5. Plants for Veterinary Uses

2.6. Plants for Ritual Uses

2.7. The Role of Mefite in the Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

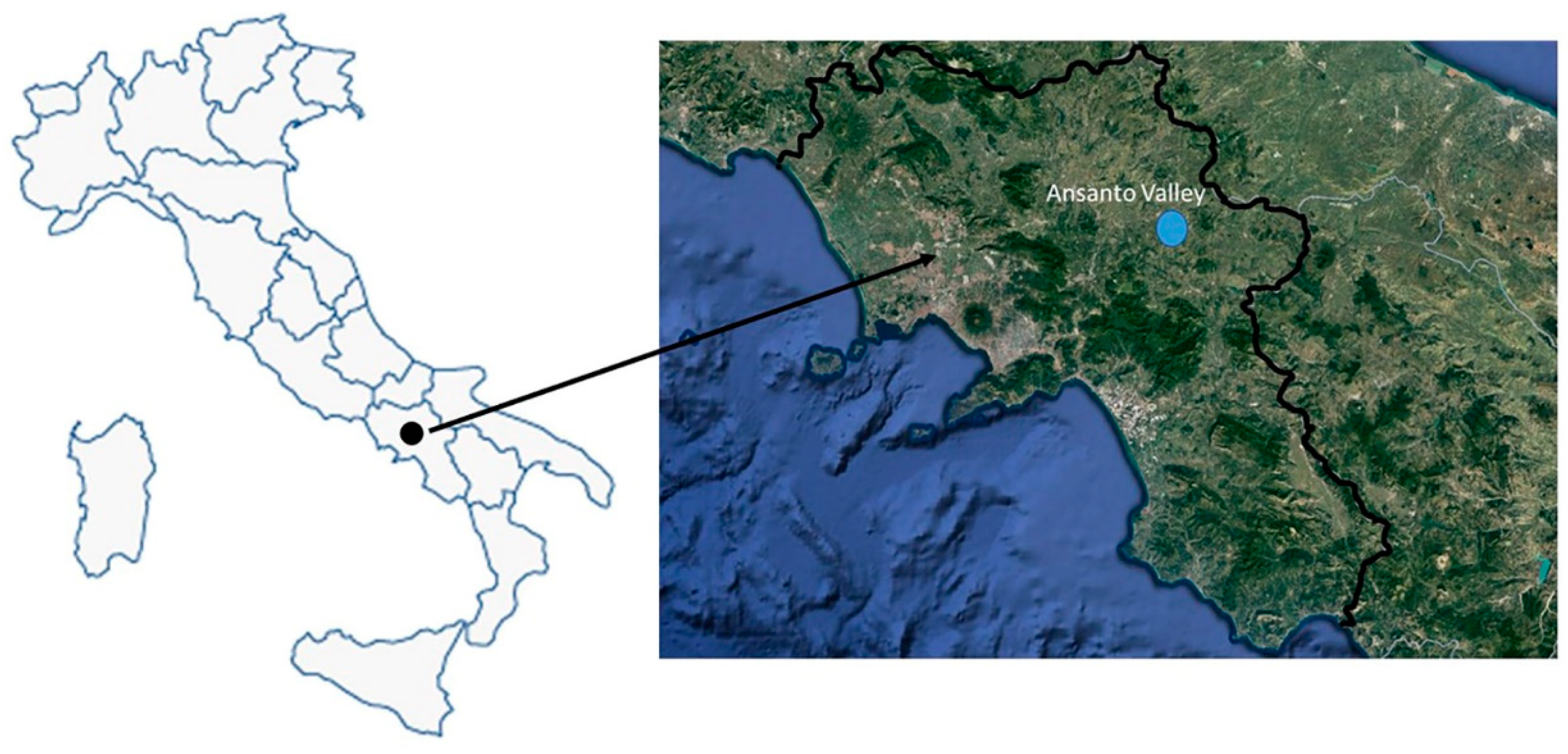

Study Area

4. Ethnobotanical Methodology

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Güneş, S.; Savran, A.; Paksoy, M.Y.; Koşar, M.; Çakılcıoğlu, U. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants in Karaisalı and Its Surrounding (Adana-Turkey). J. Herb. Med. 2017, 8, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Kaligarič, M.; Juračak, J. Divergence of Ethnobotanical Knowledge of Slovenians on the Edge of the Mediterranean as a Result of Historical, Geographical and Cultural Drivers. Plants 2021, 10, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Dolina, K.; Jeričević, M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. Insular Pharmacopoeias: Ethnobotanical Characteristics of Medicinal Plants Used on the Adriatic Islands. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 623070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Herrera, P.; Morales, P.; Cámara, M.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Tardío, J.; Sánchez-Mata, M.C. Nutritional and Phytochemical Composition of Mediterranean Wild Vegetables after Culinary Treatment. Foods 2020, 9, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. Medicinal Plants and Food Medicines in the Folk Traditions of the Upper Lucca Province, Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 70, 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idolo, M.; Motti, R.; Mazzoleni, S. Ethnobotanical and Phytomedicinal Knowledge in a Long-History Protected Area, the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park (Italian Apennines). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monari, S.; Ferri, M.; Salinitro, M.; Tassoni, A. Ethnobotanical Review and Dataset Compiling on Wild and Cultivated Plants Traditionally Used as Medicinal Remedies in Italy. Plants 2022, 11, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruschi, P.; Sugni, M.; Moretti, A.; Signorini, M.A.; Fico, G. Children’s versus Adult’s Knowledge of Medicinal Plants: An Ethnobotanical Study in Tremezzina (Como, Lombardy, Italy). Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2019, 29, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalloro, V.; Robustelli della Cuna, F.S.; Quai, E.; Preda, S.; Bracco, F.; Martino, E.; Collina, S. Walking around the Autonomous Province of Trento (Italy): An Ethnobotanical Investigation. Plants 2022, 11, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danna, C.; Poggio, L.; Smeriglio, A.; Mariotti, M.; Cornara, L. Ethnomedicinal and Ethnobotanical Survey in the Aosta Valley Side of the Gran Paradiso National Park (Western Alps, Italy). Plants 2022, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Sõukand, R.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. “We Became Rich and We Lost Everything”: Ethnobotany of Remote Mountain Villages of Abruzzo and Molise, Central Italy. Hum. Ecol. 2021, 49, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruca, G.; Spampinato, G.; Turiano, D.; Laghetti, G.; Musarella, C.M. Ethnobotanical Notes about Medicinal and Useful Plants of the Reventino Massif Tradition (Calabria Region, Southern Italy). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2019, 66, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautone, M.; De Martino, L.; De Feo, V. Ethnobotanical Research in Cava de’ Tirreni Area, Southern Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menale, B.; De Castro, O.; Di Iorio, E.; Ranaldi, M.; Muoio, R. Discovering the Ethnobotanical Traditions of the Island of Procida (Campania, Southern Italy). Plant Biosyst. 2022, 156, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Galasso, G.; Albano, A.; Alessandrini, A.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Astuti, G.; Bacchetta, G.; Ballelli, S.; Banfi, E.; et al. An Updated Checklist of the Vascular Flora Native to Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2018, 152, 179–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodini, G.; Granieri, D.; Avino, R.; Caliro, S.; Costa, A.; Minopoli, C.; Vilardo, G. Non-Volcanic CO2 Earth Degassing: Case of Mefite d’Ansanto (Southern Apennines), Italy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L211303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capano, M. Widespread Fossil CO2 in the Ansanto Valley (Italy): Dendrochronological, 14C, and 13C Analyses on Tree Rings. Radiocarbon 2013, 55, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capano, M.; Pignatelli, O.; Martinelli, N.; Gigli, S.; Terrasi, F. The Wooden Sculptures from Mefite’ Sanctuary (Southern Italy). A Dendrotypological Approach for the Analysis of Woodworking Technologies. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 38, 103403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iorio, E.; Menale, B.; Innangi, M.; Santangelo, A.; Strumia, S.; De Castro, O. An Extreme Environment Drives Local Adaptation of Genista Tinctoria (Fabaceae) from the Mefite (Ansanto Valley, Southern Italy). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2023, 202, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. The Virtues of Being Peripheral, Recreational, and Transnational: Local Wild Food and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in Selected Remote Municipalities of Calabria, Southern Italy. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sanzo, P.; De Martino, L.; Mancini, E.; Feo, V. De Medicinal and Useful Plants in the Tradition of Rotonda, Pollino National Park, Southern Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón, R.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Priestley, C.; Morales, R.; Heinrich, M. Medicinal and Local Food Plants in the South of Alava (Basque Country, Spain). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 176, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axiotis, E.; Halabalaki, M.; Skaltsounis, L.A. An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in the Greek Islands of North Aegean Region. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.I.; Cavero, R.Y. Medicinal Plants Used for Neurological and Mental Disorders in Navarra and Their Validation from Official Sources. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 169, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, M.; Carrió, E.; Bonet, M.À.; Vallès, J. Ethnobotany of the Alt Empordà Region (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). Plants Used in Human Traditional Medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 124, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixidor-Toneu, I.; Martin, G.J.; Ouhammou, A.; Puri, R.K.; Hawkins, J.A. An Ethnomedicinal Survey of a Tashelhit-Speaking Community in the High Atlas, Morocco. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 188, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattalia, G.; Sõukand, R.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Blended Divergences: Local Food and Medicinal Plant Uses among Arbëreshë, Occitans, and Autochthonous Calabrians Living in Calabria, Southern Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2020, 154, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, A.M.; Motti, R.; Weckerle, C.S. Traditional Plant Use in the Areas of Monte Vesole and Ascea, Cilento National Park (Campania, Southern Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzotti, V. Bioactive Saponins from Allium and Aster Plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2005, 4, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, M.C.; Maxia, L.; Maxia, A. Ethnobotanical Comparison between the Villages of Escolca and Lotzorai (Sardinia, Italy). J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2005, 11, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, I.; Braca, A.; Camangi, F. Tradizioni Etnofarmacobotaniche Nel Territorio Del Gabbro (Livorno-Toscana). Quad. Mus. Stor. Nat. Livorno 2015, 26, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttolomondo, T.; Licata, M.; Leto, C.; Bonsangue, G.; Letizia Gargano, M.; Venturella, G.; La Bella, S. Popular Uses of Wild Plant Species for Medicinal Purposes in the Nebrodi Regional Park (North-Eastern Sicily, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 157, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rosa, A.; Cornara, L.; Saitta, A.; Salam, A.M.; Grammatico, S.; Caputo, M.; La Mantia, T.; Quave, C.L. Ethnobotany of the Aegadian Islands: Safeguarding Biocultural Refugia in the Mediterranean. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchetti, L.; Zitti, S.; Taffetani, F. Ethnobotanical Uses in the Ancona District (Marche Region, Central Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccioni, S.; Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Bedini, G.; Guazzi, E. Ricerche Etnobotaniche in Liguria. La Riviera Spezzina (Liguria Orientale). Atti Soc. Tosc. Sci. Nat. Mem. Ser. B 2008, 115, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sanna, C.; Ballero, M.; Maxia, A. Le Piante Medicinali Utilizzate Contro Le Patologie Epidermiche in Ogliastra (Sardegna Centro-Orientale). Atti Soc. Tosc. Sci. Nat. Mem. Ser. B 2006, 113, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cornara, L.; La Rocca, A.; Marsili, S.; Mariotti, M.G. Traditional Uses of Plants in the Eastern Riviera (Liguria, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 125, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C.L.; Villanelli, M.L.; Mangino, P.; Sabbatini, G.; Santini, L.; Boccetti, T.; Profili, M.; Ciccioli, T.; Rampa, L.G.; et al. Ethnopharmacognostic Survey on the Natural Ingredients Used in Folk Cosmetics, Cosmeceuticals and Remedies for Healing Skin Diseases in the Inland Marches, Central-Eastern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 91, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleo, M.; Cambria, S.; Bazan, G. Tradizioni Etnofarmacobotaniche in Alcune Comunità Rurali Dei Monti Di Trapani (Sicilia Occidentale). Quad. Bot. Ambient. Appl. 2013, 24, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Motti, R.; Motti, P. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Useful Plants in the Agro Nocerino Sarnese (Campania, Southern Italy). Hum. Ecol. 2017, 45, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dei Cas, L.; Pugni, F.; Fico, G. Tradition of Use on Medicinal Species in Valfurva (Sondrio, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 163, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansanelli, S.; Ferri, M.; Salinitro, M.; Tassoni, A. Ethnobotanical Survey of Wild Food Plants Traditionally Collected and Consumed in the Middle Agri Valley (Basilicata Region, Southern Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Bonanomi, G.; Lanzotti, V.; Sacchi, R. The Contribution of Wild Edible Plants to the Mediterranean Diet: An Ethnobotanical Case Study Along the Coast of Campania (Southern Italy). Econ. Bot. 2020, 74, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalini, S.; Tomè, F.; Fico, G. Traditional Uses of Medicinal Plants in Valvestino (Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 121, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Forti, G.; Marignoli, S. Ethnobotanical and Ethnomedicinal Uses of Plants in the District of Acquapendente (Latium, Central Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxia, A.; Lancioni, M.C.; Balia, A.N.; Alborghetti, R.; Pieroni, A.; Loi, M.C. Medical Ethnobotany of the Tabarkins, a Northern Italian (Ligurian) Minority in South-Western Sardinia. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2008, 55, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttolomondo, T.; Licata, M.; Leto, C.; Letizia Gargano, M.; Venturella, G.; La Bella, S. Plant Genetic Resources and Traditional Knowledge on Medicinal Use of Wild Shrub and Herbaceous Plant Species in the Etna Regional Park (Eastern Sicily, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 1362–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalini, S.; Puricelli, C.; Mikerezi, I.; Iriti, M. Plants, People and Traditions: Ethnobotanical Survey in the Lombard Stelvio National Park and Neighbouring Areas (Central Alps, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortini, P.; Di Marzio, P.; Guarrera, P.M.; Iorizzi, M. Ethnobotanical Study on the Medicinal Plants in the Mainarde Mountains (Central-Southern Apennine, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 184, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leto, C.; Tuttolomondo, T.; La Bella, S.; Licata, M. Ethnobotanical Study in the Madonie Regional Park (Central Sicily, Italy)—Medicinal Use of Wild Shrub and Herbaceous Plant Species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorini, M.A.; Piredda, M.; Bruschi, P. Plants and Traditional Knowledge: An Ethnobotanical Investigation on Monte Ortobene (Nuoro, Sardinia). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballero, M.; Poli, F.; Sacchetti, G.; Loi, M.C. Ethnobotanical Research in the Territory of Fluminimaggiore (South-Western Sardinia). Fitoterapia 2001, 72, 788801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Ivancheva, S. Preliminary Comparative Analysis of Medicinal Plants Used in the Traditional Medicine of Bulgaria and Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 87, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R. Wild Plants Used as Herbs and Spices in Italy: An Ethnobotanical Review. Plants 2021, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savo, V.; Caneva, G.; Maria, G.P.; David, R. Folk Phytotherapy of the Amalfi Coast (Campania, Southern Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M. Traditional Phytotherapy in Central Italy (Marche, Abruzzo, and Latium). Fitoterapia 2005, 76, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menale, B.; Muoio, R. Use of Medicinal Plants in the South-Eastern Area of the Partenio Regional Park (Campania, Southern Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 320–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, N.G.; Guarrera, P.M.; De Fine, G. Contribution to the Knowledge of the Folk Plant Medicine in Calabria Region (Southern Italy). Fitoterapia 2007, 78, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Corradi, L. Ethnopharmacobotanical Remarks on the Province of Chieti Town (Abruzzo, Central Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 74, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menale, B.; Amato, G.; Di Prisco, C.; Muoio, R. Traditional Uses of Plants in North-Western Molise (Central Italy). Delpinoa 2006, 48, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bottoni, M.; Milani, F.; Colombo, L.; Nallio, K.; Colombo, P.S.; Giuliani, C.; Bruschi, P.; Fico, G. Using Medicinal Plants in Valmalenco (Italian Alps): From Tradition to Scientific Approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalini, S.; Iriti, M.; Puricelli, C.; Ciuchi, D.; Segale, A.; Fico, G. Traditional Knowledge on Medicinal and Food Plants Used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy)—An Alpine Ethnobotanical Study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Lucia, L.M. Ethnobotanical Remarks on Central and Southern Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmese, M.T.; Manganelli, R.E.U.; Tomei, P.E. An ethno-pharmacobotanical survey in the Sarrabus district (south-east Sardinia). Fitoterapia 2001, 72, 619–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttolomondo, T.; Licata, M.; Leto, C.; Savo, V.; Bonsangue, G.; Letizia Gargano, M.; Venturella, G.; La Bella, S. Ethnobotanical Investigation on Wild Medicinal Plants in the Monti Sicani Regional Park (Sicily, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 568–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Savo, V.; Caneva, G. Traditonal Uses of Plants in the Tolfa-Cerite-Manziate Area (Central Italy). Ethnobiol. Lett. 2015, 6, 119–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Sõukand, R.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Dissymmetry at the Border: Wild Food and Medicinal Ethnobotany of Slovenes and Friulians in NE Italy. Econ. Bot. 2020, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Bonanomi, G.; Emrick, S.; Lanzotti, V. Traditional Herbal Remedies Used in Women’s Health Care in Italy: A Review. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 941–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellia, G.; Pieroni, A. Isolated, but Transnational: The Glocal Nature of Waldensian Ethnobotany, Western Alps, NW Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menale, B.; De Castro, O.; Cascone, C.; Muoio, R. Ethnobotanical Investigation on Medicinal Plants in the Vesuvio National Park (Campania, Southern Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 192, 320–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Antignani, V.; Idolo, M. Traditional Plant Use in the Phlegraean Fields Regional Park (Campania, Southern Italy). Hum. Ecol. 2009, 37, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; de Falco, B. Traditional Herbal Remedies Used for Managing Anxiety and Insomnia in Italy: An Ethnopharmacological Overview. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camangi, F.; Stefani, A.; Tomei, P.E. Il Casentino: Tradizioni Etnofarmacobotaniche Nei Comuni Di Poppi e Bibbiena (Arezzo-Toscana). Atti Soc. Tosc. Sci. Nat. Mem. Ser. B 2003, 110, 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Impieri, M. Ethnobotanical Notes about Some Uses of Medicinal Plants in Alto Tirreno Cosentino Area (Calabria, Southern Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Ippolito, F.; Bonanomi, G. Folk Phytotherapy in Paediatric Health Care in Central and Southern Italy: A Review. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Pieroni, A. Renegotiating Situativity: Transformations of Local Herbal Knowledge in a Western Alpine Valley during the Past 40 Years. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galuzzo, F.; Attard, E.; Di Gioia, D. Emilia Romagna and Malta: A Comparative Ethnobotanical Study. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2021, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomaria, B. Le Piante Di Uso Popolare Nel Territorio Di Camerino (Marche). Arch. Bot. E Biogeogr. Ital. 1982, 58, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Ghedira, K. Comparative Analysis of Medicinal Plants Used in Traditional Medicine in Italy and Tunisia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Paura, B.; Cozzolino, A.; Falco, B. de Edible Flowers Used in Some Countries of the Mediterranean Basin: An Ethnobotanical Overview. Plants 2022, 11, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Natale, A.; Pollio, A. Plants Species in the Folk Medicine of Montecorvino Rovella (Inland Campania, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 109, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Novella, R.; Di Novella, N.; De Martino, L.; Mancini, E.; De Feo, V. Traditional Plant Use in the National Park of Cilento and Vallo Di Diano, Campania, Southern, Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakilcioglu, U.; Turkoglu, I. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Sivrice (Elazıĝ-Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 132, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrió, E.; Vallès, J. Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants Used in Eastern Mallorca (Balearic Islands, Mediterranean Sea). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Hodak, A.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Marić, M.; Juračak, J. Traditional Ethnobotanical Knowledge of the Central Lika Region (Continental Croatia)—First Record of Edible Use of Fungus Taphrina Pruni. Plants 2022, 11, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarić-Kundalić, B.; Dobeš, C.; Klatte-Asselmeyer, V.; Saukel, J. Ethnobotanical Survey of Traditionally Used Plants in Human Therapy of East, North and North-East Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 1051–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. Local Plant Resources in the Ethnobotany of Theth, a Village in the Northern Albanian Alps. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2008, 55, 1197–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Pavesi, A. New or Uncommon Uses of Several Medicinal Plants in Some Areas of Central Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1990, 29, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, B.; Hajdari, A.; Pajazita, Q.; Syla, B.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. An Ethnobotanical Survey of the Gollak Region, Kosovo. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakilcioglu, U.; Khatun, S.; Turkoglu, I.; Hayta, S. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants in Maden (Elazig-Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakir, H.; Korkmaz, M.; Güller, B. Medicinal Plant Diversity of Western Mediterrenean Region in Turkey. J. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2009, 3, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, F.; Šolić, I.; Dujaković, M.J.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Grdiša, M. The First Contribution to the Ethnobotany of Inland Dalmatia: Medicinal and Wild Food Plants of the Knin Area, Croatia. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2019, 88, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesano, V.; Negro, D.; Sarli, G.; De Lisi, A.; Laghetti, G.; Hammer, K. Notes about the Uses of Plants by One of the Last Healers in the Basilicata Region (South Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C.L.; Santoro, R.F. Folk Pharmaceutical Knowledge in the Territory of the Dolomiti Lucane, Inland Southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 95, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 9Rivera, D.; Verde, A.; Fajardo, J.; Obón, C.; Consuegra, V.; García-Botía, J.; Ríos, S.; Alcaraz, F.; Valdés, A.; Moral, A.d.; et al. Ethnopharmacology in the Upper Guadiana River Area (Castile-La Mancha, Spain). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 241, 111968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mokasabi, F. The State of the Art of Traditional Herbal Medicine in the Eastern Mediterranean Coastal Region of Libya. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2014, 21, 575–582. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmet Sargin, S. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Bozyazi District of Mersin, Turkey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 9Bulut, G. Medicinal and Wild Food Plants of Marmara Island (Balikesir–Turkey). Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae 2016, 85, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavero, R.Y.; Akerreta, S.; Calvo, M.I. Pharmaceutical Ethnobotany in Northern Navarra (Iberian Peninsula). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Baceta, G.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Molina, M.; Reyes-García, V.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M. Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used in the Northwest of the Basque Country (Biscay and Alava), Iberian Peninsula. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 152, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuzlaci, E.; Şenkardeş, I. Turkish Folk Medicinal Plants, X: Ürgüp (Nevşehir). Marmara Pharm. J. 2011, 15, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, O.; Khalil, K.; Fulder, S.; Azaizeh, H. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Herbs in Israel, the Golan Heights and the West Bank Region. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 83, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale Della Repubblica Italiana. Available online: http://www.agricoltura.regione.campania.it/tipici/pdf/PAT_2021.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Martin, J.G. Ethnobotany: A Methods Manual, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, M.; Lardos, A.; Leonti, M.; Weckerle, C.; Willcox, M.; Applequist, W.; Ladio, A.; Lin Long, C.; Mukherjee, P.; Stafford, G. Best Practice in Research: Consensus Statement on Ethnopharmacological Field Studies—ConSEFS. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 211, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, J.P. Politics, Culture, and Governance in the Development of Prior Informed Consent in Indigenous Communities. Curr. Anthropol. 2006, 47, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatti, S. Flora d’Italia; Edagricole: Bologna, Italy, 1982; Volumes 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- WFO. World Flora Online. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Chase, M.W.; Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Fay, M.F.; Byng, J.W.; Judd, W.S.; Soltis, D.E.; Mabberley, D.J.; Sennikov, A.N.; Soltis, P.S.; Stevens, P.F.; et al. An Update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group Classification for the Orders and Families of Flowering Plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 181, 12385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummitt, P.K.; Powell, C.E. Authors of Plant Names; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Richmond, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D.; Allkin, R.; Obon, C.; Alcaraz, F.; Verpoorte, R.; Heinrich, M. What Is in a Name? The Need for Accurate Scientific Nomenclature for Plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 152, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckerle, C.S.; de Boer, H.J.; Puri, R.K.; van Andel, T.; Bussmann, R.W.; Leonti, M. Recommended Standards for Conducting and Reporting Ethnopharmacological Field Studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 210, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal Plants in Mexico: Healers’ Consensus and Cultural Importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.A.; García-Barriuso, M.; Amich, F. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used in the Arribes Del Duero, Western Spain. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 131, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabesh, J.M.; Prabhu, S.; Vijayakumar, S. An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by Traditional Healers in Silent Valley of Kerala, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Motti, R.; Marotta, M.; Bonanomi, G.; Cozzolino, S.; Di Palma, A. Ethnobotanical Documentation of the Uses of Wild and Cultivated Plants in the Ansanto Valley (Avellino Province, Southern Italy). Plants 2023, 12, 3690. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12213690

Motti R, Marotta M, Bonanomi G, Cozzolino S, Di Palma A. Ethnobotanical Documentation of the Uses of Wild and Cultivated Plants in the Ansanto Valley (Avellino Province, Southern Italy). Plants. 2023; 12(21):3690. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12213690

Chicago/Turabian StyleMotti, Riccardo, Marco Marotta, Giuliano Bonanomi, Stefania Cozzolino, and Anna Di Palma. 2023. "Ethnobotanical Documentation of the Uses of Wild and Cultivated Plants in the Ansanto Valley (Avellino Province, Southern Italy)" Plants 12, no. 21: 3690. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12213690

APA StyleMotti, R., Marotta, M., Bonanomi, G., Cozzolino, S., & Di Palma, A. (2023). Ethnobotanical Documentation of the Uses of Wild and Cultivated Plants in the Ansanto Valley (Avellino Province, Southern Italy). Plants, 12(21), 3690. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12213690